Abstract

This retrospective cohort study examined rates of conformance to continuity of care treatment guidelines and factors associated with conformance for persons with schizophrenia. Subjects were 8,621 adult Ohio Medicaid recipients, aged 18–64, treated for schizophrenia in 2004. Information on individual-level (demographic and clinical characteristics) and contextual-level variables (county socio-demographic, economic, and health care resources) were abstracted from Medicaid claim files and the Area Resource File. Outcome measures captured four dimensions of continuity of care: (1) regularity of care; (2) transitions; (3) care coordination, and (4) treatment engagement. Multilevel modeling was used to assess the association between individual and contextual-level variables and the four continuity of care measures. The results indicated that conformance rates for continuity of care for adults with schizophrenia are below recommended guidelines and that variations in continuity of care are associated with both individual and contextual-level factors. Efforts to improve continuity of care should target high risk patient groups (racial/ethnic minorities, the dually diagnosed, and younger adults with early onset psychosis), as well as community-level risk factors (provider supply and geographic barriers of rural counties) that impede access to care.

Keywords: Continuity of care, Schizophrenia, Quality of care, Medicaid

Continuity of care is considered to be a critical indicator of quality of care and key to effective management of schizophrenia. Yet the provision of high-quality, appropriate and effective services to this population is challenging because of the chronic nature of the illness, functional limitations, and associated psychiatric and medical comorbidities (American Psychiatric Association 2004a, b; Buckley et al. 2009). For individuals with schizophrenia, good care requires access to a comprehensive array of services (acute, long-term, and rehabilitative), continuity of care over time, and extensive coordination across providers, funding sources, and service delivery systems (Anderson and Knickman 2001; Gelber and Dougherty 2005; Vladeck 2001).

Unfortunately, services in the de facto mental health system are often fragmented, decentralized, and uncoordinated, forcing persons with schizophrenia to navigate a complex system to obtain appropriate care (Anderson and Knickman 2001; Regier et al. 1993; Vladeck 2001). Variations in quality of care are also well documented (Institute of Medicine (U.S) 2001; Lehman and Steinwachs 1998; Young et al. 1998, 2006). In a statewide study of adults with schizophrenia in Florida's Medicaid program, only one-third met the quality standard for visit continuity (e.g., no break in mental health visits of >60 days) during the acute phase of treatment and one-fifth during the maintenance phases (Busch et al. 2009). Another study using national data of adults with schizophrenia treated by psychiatrists in routine practice found that only 8 % of Medicare patients and 41 % of Medicaid patients received psychotherapy from a mental health provider in the past 30 days (West et al. 2005). Discontinuity of care increases the risk for a number of negative outcomes including repeat hospitalizations, homelessness, incarceration, and, at worst, suicide (Fortney et al. 2003; Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009).

Only a few studies have examined factors associated with variations in continuity of care. These studies are difficult to compare, with often inconsistent findings due to differing definitions of continuity of care, study populations, and treatment settings (Johnson et al. 1997). The underdevelopment of standard measures on continuity of care has been a major impediment (Adair et al. 2003; Burns et al. 2009; Joyce et al. 2004). Much of this research is also at least 20 years old and focused on conceptual and theoretical issues (Adair et al. 2003), while empirical studies are limited by short follow-up time periods and operational definitions of continuity of care that are unidimensional and discharge-based (Wierdsma et al. 2009).

Moreover, most studies have focused almost exclusively on the effects of individual-level risk factors (e.g., demographic and clinical factors) on continuity of care (Crawford et al. 2004). However, health service researchers have increasingly recognized the importance of contextual or community-level factors (e.g., health market factors, population demographics) in promoting or impeding access to care and mental health outcomes, and the need for comprehensive models that account for the contribution of both individual and contextual factors simultaneously (Davidson et al. 2004; Phillips et al. 1998).

The primary aims of this study were: (1) to determine the rates of conformance to continuity of care treatment guidelines for persons with schizophrenia; and (2) to identify individual and contextual-level factors associated with continuity of care. The study builds upon previous research in several ways. First, we use population data to assess quality of care. Second, we examine multiple dimensions of continuity of care (e.g., regularity of care, service transitions, coordination of care) with longitudinal measures based on empirical evidence or consensus opinion. Finally, we explore the combined effect of individual and contextual factors on continuity of care. A greater understanding of factors associated with continuity of care may help to identify and target patient subgroups at high risk for discontinuity of care and critical time periods to intervene and also may inform quality improvement initiatives.

Background

Conceptual Framework

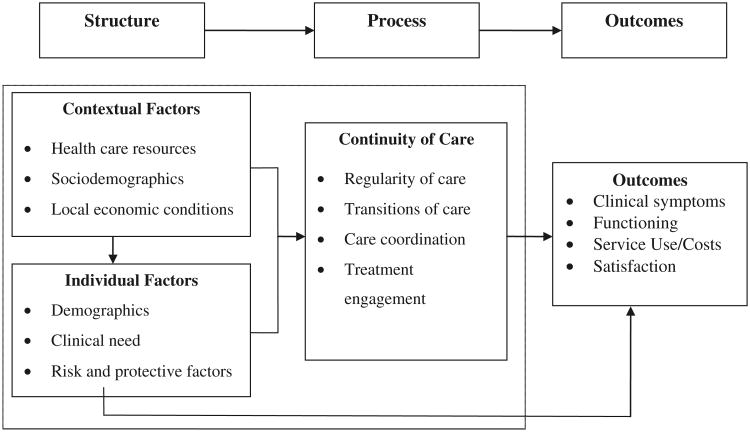

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework used to guide our analysis. The framework is based on Donabedian's (1980) tripartite conceptualization of quality, the work of McGlynn et al. (1988) on quality of mental health services, and the contribution of other scholars (e.g., Salzer et al. 1997). Donabedian (1980) classified quality as having three components of care: structure, process, and outcomes. For the purposes of this study, we focus on the effects of individual and contextual-level structural factors on continuity of care processes. The area within the dotted lines represents the key relationships of interest.

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of continuity of care.

Structural factors are defined as characteristics of the community, health care delivery system, and client population that influence the process of care and outcomes (McGlynn et al. 1988). Community-level factors likely to influence continuity of care include the availability and accessibility of health care resources, population demographics, and economic conditions within a geographic area (Davidson et al. 2004). Individual-level factors likely to influence continuity of care include client demographic characteristics that may predispose one to seek care, clinical need and illness factors, and risk and protective factors (McGlynn et al. 1988). Process of care focuses on the specific aspects of treatment and includes both “interpersonal” (e.g., therapeutic relationship between client and provider) and “technical” (e.g., use of appropriate intervention strategies and skill in implementing these strategies) components of care (Donabedian 1988). In our model, continuity of care is a “technical” process measure conceptualized as appropriate care; that is, meeting criteria for standards of care or practice guidelines based on either research evidence or expert consensus opinion. We examine four separate but related concepts of continuity of care: regularity of care, transitions of care, care coordination, and treatment engagement. As shown in Fig. 1, relevant mental health outcomes are affected by client characteristics (e.g., severity of illness) and treatment processes and can be measured by changes in clinical symptoms and functioning, service use and costs, and patient satisfaction.

Individual-Level Factors

Numerous reviews (see Crawford et al. 2004; Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009; O'Brien et al. 2009) have examined demographic and clinical characteristics associated with discontinuity of care for persons with schizophrenia and other severe mental illness. Demographic factors most consistently associated with poor continuity of care include younger age, male sex, minority ethnicity (with blacks and Hispanics having worse outcomes than whites), low income, and other indicators of social disadvantage (e.g., unemployment, lack of health insurance, and low educational attainment) (Kessler et al. 2001; Kuno and Rothbard 2002; O'Brien et al. 2009; Stein et al. 2007). Clinical factors including substance abuse comorbidity, greater symptom severity, lack of regular source of outpatient care, and poor medication compliance are all factors that complicate treatment of schizophrenia and increase the likelihood of poor continuity of care (Busch et al. 2009; Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009; Olfson et al. 2010). Social circumstances such as living situation, level of family involvement and social support also appear to have a profound impact on treatment adherence for persons with schizophrenia. Being single or divorced, living alone, socially isolated, having no contact with family or homelessness are associated with increased risk for discontinuity of care and/or treatment drop out (Crawford et al. 2004; O'Brien et al. 2009). Homeless adults, in particular, are difficult to engage in treatment; less than half receive any psychiatric treatment and those who do tend to overuse inpatient and emergency room services but underuse outpatient services (O'Brien et al. 2009).

Contextual-Level Factors

As shown in Fig. 1, community characteristics such as health care resources, population demographics, and local economic conditions are important determinants of access to mental health care. Health care system resources including both the supply and distribution of providers and health facilities in an area can influence continuity of care by either promoting or impeding access to mental health services (Aday and Andersen 1974; Lambert et al. 1999; Litaker and Love 2005; Phillips et al. 1998). For example, research has shown that greater availability of services (e.g., psychiatrists and primary care physicians per capita, community mental health centers, and inpatient psychiatric units) is associated with both increased access to and increased utilization of mental health care (Fortney et al. 2009; Hendryx and Rohland 1994; Hendryx et al. 1995; Olfson et al. 2010).

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the county population (e.g., percentage of residents living in poverty, unemployed, from racial/ethnic minority groups, and urban/rural location) can also influence access to mental health care by affecting level of health need, availability of resources, and norms and beliefs about mental illness and perceived public stigma (Robert 1999). Geographic variation in health care utilization and health outcomes is well-documented in the research literature, with poorer access for individuals living in both urban and rural areas (Fisher et al. 2003; Fuchs 2004; Wennberg and Wennberg 2003). Studies suggest that individuals living in low-income urban communities characterized by high rates of poverty and uninsurance and non-white populations have more difficulty obtaining needed health services or specialized treatment and suffer from worse health outcomes compared to individuals living in higher income communities (Chow et al. 2003; Gresenz et al. 2000; IOM 2003). The mechanisms for these economic and geographic disparities are complex and not fully understood; however, it is thought that poverty coupled with compositional factors of communities (e.g., high prevalence of individuals with severe mental illness residing in inner city areas) creates unfavorable financial and health care market conditions that result in decreased access to primary and specialty care for both insured and uninsured community residents (IOM 2003). For example, when subsidies fail to cover the cost of uncompensated care, providers and health facilities then limit the quantity and availability of health services and/or may relocate to more affluent areas (Bazzoli et al. 2005; Cunningham et al. 2008; Pauly and Paga′n 2007). Consequently, vulnerable populations such as those with schizophrenia who rely on public insurance must compete for already limited access to safety-net providers (Davidson et al. 2004). Similar effects are found in rural communities although the dynamics are different. Shortages of providers and associated access barriers related to waiting lists, travel costs, and culturally mediated attitudes about mental illness all contribute to poor access to care (Lambert and Agger 1995; Mayer et al. 2005; Reschovsky and Staiti 2005; Wagenfeld et al. 1994).

Continuity of Care

Definitions of continuity of care in mental health have varied considerably in depth and scope in the theoretical literature; consequently, operationalization and measurement of the concept has been difficult (Burns et al. 2009). Despite the varying definitions and lack of agreement on dimensions, researchers agree that continuity of care is a multidimensional concept with both longitudinal and cross-sectional elements (Johnson et al. 1997; Wierdsma et al. 2009). Longitudinal or temporal continuity signifies care that is continuous over time (Bachrach 1981). Cross-sectional continuity refers to the comprehensiveness (e.g., availability of a broad range of services) and integration of services at any given time (Brekke and Test 1992; Test 1979).

In this study, we define continuity of care as the pattern of outpatient mental health service use over time. We examine four separate dimensions of continuity of care that have been used in prior studies (Fortney et al. 2003; Greenberg et al. 2003): (1) regularity of care, e.g., “evenness' of service use over time or care that lacks temporal gaps or breaks in treatment; (2) transitions of care, e.g., continuous treatment through transitions between services settings (e.g., inpatient to outpatient services); (3) care coordination, e.g., provisions that patient needs for health services are met and the integration of services across people, functions, and sites; and (4) treatment engagement, e.g., degree of involvement in the mental health treatment process as evidenced by attendance at follow-up appointments (O'Brien et al. 2009). Three of these dimensions capture longitudinal aspects of continuity, while one captures the cross-sectional elements.

Methods

Design and Study Cohort

A retrospective cohort design was used to examine correlates of continuity of care among Medicaid-enrolled adults with schizophrenia. The study population included all adults between the ages of 18 and 64 who were: classified as disabled; had two or more outpatient mental health visits associated with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition [ICD-9-CM] code 295.00–295.99) during fiscal year 2004 (July 1, 2003 to June 30, 2004); and were continuously enrolled in Ohio's Medicaid program during the one-year follow-up period after their index claim (N = 17,419). Excluded were patients dual-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (N = 7,620) and those living in an institutional placement (e.g., nursing homes) for three or more months during the year (N = 1,176). These patient groups were excluded because: (1) complete information on service utilization was not available for dual-eligibles; and (2) it was assumed that adults living in an institutional setting would not be receiving ambulatory services. The authors were unable to extend the time period beyond 2004 because adult Medicaid enrollees with disabilities were mandated to enroll in managed care the following year. This yielded a final analytic sample of 8,623.

Data Sources

Data were extracted from three sources: Medicaid fee-forservice claims, the Area Resource File, and the Ohio State Psychology and Social Work Licensure Boards. Individual-level data were abstracted from Medicaid eligibility and claims files. Medicaid eligibility files provided information on the enrollee's age, race/ethnicity, gender, marital status, county of residence, and living arrangement. Claims data files provided information on encounters for inpatient and outpatient services provided in physicians' offices, institutional settings, and community health clinics; the files also included dates of service, principal and secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, Healthcare Common Procedure [HCPCS] codes, and provider specialty. Community-level data were abstracted from the Area Resource File and the Ohio State Licensure Boards. The 2004 Area Resource File (Quality Resource Systems 2009) provided information on socio-demographic, economic, and health care system characteristics for Ohio's 88 counties. The Ohio State Board of Psychology and Social Work provided information on the number of psychologists and social workers within each county. Medicaid claims and eligibility files were linked to the other data using county identifiers. This study was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Dependent Variables: Continuity of Care Measures

Hermann et al. (2002) identified 42 process measures that assess various domains of quality of care for schizophrenia. In this study, we used six of the 42 measures that assessed continuity of care and could be constructed from administrative data that were then evaluated on a conceptual framework that emphasized: (1) level of research evidence (e.g., randomized clinical trials or observational studies); (2) feasibility (e.g., availability and accessibility of data); and (3) clinical meaningfulness (e.g., validity of quality measures) (Hermann and Palmer 2002). Table 1 summarizes the measure used in this study including specifications, rationale, and level of research evidence associated with each measure.

Table 1. Quality measures of continuity of care for the treatment of schizophrenia.

| Measure | Criteria | Guideline-based rationale | Evidence ratinga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regularity of care | |||

| Medication management | ≥1 medication management visits with a psychiatrist every 90 days for adults with schizophrenia during a 12 month period | Antipsychotic medications are effective in the treatment of acute exacerbation of schizophrenia but patients need to be seen on a regular basis by a physician to monitor changes in symptoms and adverse side effects | C |

| Availability of outpatient treatment | ≥1 outpatient visits every 90 days for adults with schizophrenia during a 12 month period | As a minimal standard of care, periodic outpatient visits by a mental health practitioner are necessary for patients with schizophrenia to prevent relapse | C |

| Transitions of care | |||

| Intensity of aftercare | ≥1 outpatient visit per month for 180 day period after discharge from psychiatric hospital for adults with schizophrenia | Timely and appropriate aftercare is necessary, particularly during the first few months after discharge to prevent readmission, relapse, and suicidal behavior | B |

| Care coordination | |||

| Case management | ≥1 visit by a case manager every 90 days for adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had ≥2 hospitalizations or ≥4 emergency room visits during a 12 month period | Intensive case management, particularly assertive community treatment, has been shown to be effective in reducing psychiatric hospitalizations for high users | A |

| Substance abuse or dependence treatment | ≥4 outpatient psychiatric visits and 4 substance abuse visits for adults diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance-related disorder | Comorbid substance abuse is common among schizophrenia patients and associated with a number of negative outcomes. Research studies have found that providing appropriate treatment for both conditions is associated with an increased likelihood of abstinence, improved psychiatric outcomes, and lower likelihood of hospitalization | B |

| Treatment engagement | |||

| Adult who had a psychiatric evaluation or new exacerbation of schizophrenia had a second outpatient mental health visit within 14–90 days | Research has shown that 30–50 % of individuals with severe mental illness fail to attend scheduled outpatient visits. After the initial psychiatric evaluation, patients should be seen frequently | C |

Source for criteria: Hermann et al. (2002)

AHRQ rating categories were used to assess the research evidence: A good research evidence, B fair research evidence, C no research evidence, clinical consensus or opinion that good continuity of care would prevent emergency room use and hospitalization

Regularity of Care Two measures were used to assess regularity of care: (1) “medication management,” the number of adults with schizophrenia who had at least one medication management visit with a psychiatrist every 90 days (Healthcare Common Procedure [HCPCS] codes: 90862, 99202–99205, 99211–99215, 99241–99245, 99385–99402) during a 12-month period; and (2) “outpatient treatment,” the number of adults with schizophrenia who had at least one outpatient visit every 90 days during a 12-month period. Outpatient visits were defined as any services where the main reason for the visits was for mental health treatment, the provider was a mental health practitioner, and the duration of treatment was less than 23 h. These services included: individual or group psychotherapy (HCPCS codes: 90804–90814, 90846–90849, 90853, 90857, 90887, 90899); crisis intervention (HCPCS code: Z1837); partial hospitalization (HCPCS code: Z1838); diagnostic assessment (HCPCS codes: 90801, 90802, Z1832); and psychiatric rehabilitation services (HCPCS codes: Z1840, Z1841). Excluded were emergency room visits or 23-h stays for observation because it was assumed that good continuity of care would prevent emergency room use and hospitalization.

Transitions of Care The timeliness of follow-up care after psychiatric hospitalization—“intensity of aftercare”—was measured by the number of adults with schizophrenia who had at least one outpatient visit (includes medication management, psychotherapy, and other outpatient services) every 30 days for 6 months after discharge.

Care Coordination Two measures were used to measure care coordination. The first, “case management,” assessed the proportion of adults with schizophrenia who were high users (defined as four emergency room visits or two hospitalizations) that had at least one case management visit every 90 days during a twelve-month period. The second, “substance-abuse case management,” assessed the proportion of adults with schizophrenia and a substance-related disorder that had at least four outpatient substance abuse visits and four psychiatric visits (codes are listed above under outpatient visits) during a 12-month period.

Treatment Engagement This measure, developedbyValue Options in response to the high rates of early termination and treatment drop-out for persons with severe mental illness, assessed the proportion of adults who had a psychiatric diagnostic evaluation (HCPCS codes: 9080, 90801, 90802) for a new exacerbation of schizophrenia (defined as no outpatient encounters in the 90 days prior to the diagnostic evaluation) and had a second outpatient mental health visit (medication management and outpatient visits listed above) within 14–90 days (Hermann et al. 2002).

Independent Variables

Individual-Level Factors Demographic characteristics included age, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, or Other), gender, marital status (single, married, other), and most frequent living situation (independent living, living with family, homeless or shelter, or community residential program). Clinical characteristics included primary diagnosis (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder), comorbid psychiatric and medical disorders, and prior psychiatric hospitalizations during the past year. Three dichotomous variables were used to measure common comorbid psychiatric disorders among schizophrenics: substance abuse (ICD-9-CM codes: 291, 292, 303–305); anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 300–300.3, 308.3); and depressive disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (Charlson et al. 1987) was used to measure the existence and severity of medical co-morbidities. Theoretically, scores could range from 0 to 37 with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness. Individuals were classified as having comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders if they had two or more outpatient claims associated with the corresponding diagnostic codes.

Contextual-Level Factors Socio-demographic and economic variables were based on the 2004 U.S. Census, including the percentage of the county's population that was African American, Hispanic, unemployed, living in poverty, and below the median household income. Rurality was measured by the 2003 rural/urban continuum which classifies counties into nine distinct categories based on population, degree of urbanization, and proximity to metropolitan areas (Quality Resource Systems 2009). Health providers and facilities included the number of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers per 10,000 residents and the number of community mental health centers within each county (Quality Resource Systems 2009).

Data Analysis

Conformance rates, defined as the proportion of eligible adults (denominator) who had a particular characteristic (numerator), were calculated for each of the continuity of care measures based on the designated criteria (Table 1). Descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of patient demographic, clinical characteristics and contextual-level characteristics. To examine the association between individual and contextual-level variables and continuity of care, separate multivariable random-effects logistic regression models were fitted for each of the four outcomes (medication management, outpatient treatment, intensity of aftercare, and case management). Random-effects logistic regression is the appropriate analyses for multilevel or hierarchical data with binomial outcomes because it takes into account the nesting of individuals within counties and generates unbiased estimates, as well as correct standard errors. Independent variables entered into the models included patient demographic, clinical, and community factors. These analyses were not conducted for the substance-abuse care coordination due to the very low conformance rate (3.5 %) as well as treatment engagement due to its very high conformance rate (88 %). All analyses were conducted using STATA, version 11.0.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort. The mean age was 43. Over half of the patients were female, 55.7 % were white, 41.8 % were black, and 2.5 % were of other race and ethnic backgrounds (primarily Hispanic). Nearly all of the patients were living independently (92.9 %) and most were single (64.3 %). 62 % of patients were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, the remainder with schizophrenia. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the 88 counties in the state of Ohio. The socio-demographic and economic characteristics varied substantially, with the percentage of blacks ranging from 0.06 to 9.9 % per county, the percentage living in poverty ranging from 5.0 to 20.0 %, and the percentage unemployed among those 16 years of age or older ranging from 3.5 to 18.0 %. 46 % of the state population resides in metropolitan areas (defined as an urban area of 50,000 or more), a third reside in non-metropolitan, “micropolitan” areas (defined as an urban population of at least 10,000 but less than 50,000) and over a fifth reside in rural areas. The number of health care providers and community mental health centers within the counties also varied. Social workers were the largest group of providers, while psychiatrists were the smallest. Notably 27 counties have no psychiatrists, 11 have no psychologists and 77 had no community mental health centers.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of Medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Count | 8,623 | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 43 ± 11 | |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| White | 4,804 | 55.71 |

| Black | 3,606 | 41.82 |

| Other | 213 | 2.47 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4,059 | 47.07 |

| Female | 4,564 | 52.93 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5,542 | 64.27 |

| Married | 521 | 6.04 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 2,560 | 29.69 |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Independent living | 8,018 | 92.98 |

| Living with family | 150 | 1.74 |

| Homeless or shelter | 99 | 1.15 |

| Residential program | 356 | 4.13 |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia | 3,308 | 38.36 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 5,315 | 61.64 |

| Co-occurring psychiatric disorders | ||

| Substance abuse | 602 | 6.98 |

| Anxiety | 221 | 2.56 |

| Depressive | 936 | 10.85 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 6,531 | 75.74 |

| 1 | 1,604 | 18.60 |

| 2 | 330 | 3.83 |

| ≥3 | 158 | 1.83 |

| Prior hospitalizations | 1,689 | 19.59 |

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for county-level variables, Ohio.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Percent African American | 5.5 | 3.5 | 0.06 | 9.9 |

| Percent Hispanic | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 2.5 |

| Per capita income ($) | 41,928 | 4,787 | 28,859 | 75,098 |

| Percent living in poverty | 13.0 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 20.0 |

| Percent unemployed | 6.4 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 18.0 |

| Rurality: urban influence code (%) | ||||

| 1 (most urban) | 51.27 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 33.76 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 4.67 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 1.35 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 6.68 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 1.07 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | 0.17 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 0.03 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | 0.87 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 10 (most rural) | 0.13 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Health system characteristics | ||||

| Psychiatrists per 10,000 pop. | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| Psychologists per 10,000 pop. | 1.9 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 |

| Social workers per 10,000 pop. | 13.0 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 17.0 |

| No. community mental health centers | 1.07 | 1.03 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

Data are based on 88 counties in Ohio

Conformance Rates

Table 4 presents the conformance rates for measures within each of the four continuity of care domains. About two-thirds (66.3 %) of the patients had at least one medication management visit by a psychiatrist and at least one outpatient visit (67.5 %) on a regular basis. Of the patients who were hospitalized (N = 5,823 of 8,623), only 15.2 % received a follow-up visit during each 30 day period for 6 months after discharge. With regard to care coordination, 64 % of the patients who were high users of mental health services (N = 1,544 of 2,408) had at least one case management visit on a regular basis, while only 3.5 % (N = 21 of 621) of patients with co-occurring schizophrenia and substance-abuse disorders received treatment for both disorders on a regular basis. Among patients with a new episode of schizophrenia (N = 1,074 of 1,223), the vast majority (87.8 %) had their second outpatient visit within 14–90 days of the initial psychiatric evaluation.

Table 4. Conformance rates of continuity of care for adults with schizophrenia.

| Eligible | Conformance rates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| N | N | % | |

| Regularity of care | |||

| ≥1 medication management visit every 90 days for 12 month period | 8,623 | 5,714 | 66.26 |

| ≥1 outpatient visit every 90 days for a 12 month period | 8,623 | 5,823 | 67.53 |

| Transitions of care | |||

| ≥1 visit each 30 day interval in a 180 day period after discharge from inpatient mental health care | 3,484 | 529 | 15.18 |

| Care coordination | |||

| ≥4 outpatient psychiatric visits and 4 substance abuse visits for adults diagnosed with schizophrenia and substance-related disorder | 602 | 21 | 3.49 |

| ≥1 visit by a case manager every 90 days for adults who are high users of mental health with 2 or more inpatient stays or 4 ER visits in the year | 2,408 | 1,544 | 64.12 |

| Treatment engagement | |||

| Second outpatient mental health visit within 14–90 days for adults who had a psychiatric evaluation or new exacerbation of schizophrenia | 1,223 | 1,074 | 87.82 |

Factors Associated with Continuity of Care

Table 5 presents the estimated odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI) from the random effects logistic regression models on the associations between individual and contextual-level characteristics for the four continuity of care outcome measures—medication management, outpatient treatment, intensity of aftercare, and case management. The odds ratios generated from the regression model statistics (model Chi square or log likelihood test) for each of the outcomes are also shown in Table 5 while model Chi square, degrees of freedom, and overall p-values are shown in the footnote. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate better continuity of care, while those less than 1 indicate worse continuity of care. Results for the individual and contextual-level characteristics are described separately below.

Table 5. Odds ratios (OR) and 95 % CI from random-effects logistic regression models of continuity of care.

| Medication managementa | Outpatient treatmenta | Intensity of aftercarea | Case managementa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Individual-level factors | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Demographics | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age, for a 10 year increase | 1.14 | 1.08–1.19 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 1.08–1.19 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 0.93–1.13 | 0.649 | 1.22 | 1.11–1.33 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity (whiteb) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Black | 0.76 | 0.68–0.85 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.76–0.95 | 0.006 | 0.77 | 0.60–0.97 | 0.028 | 0.83 | 0.67–1.03 | 0.090 |

| Other | 0.90 | 0.56–1.45 | 0.677 | 0.72 | 0.46–1.15 | 0.171 | 0.74 | 0.27–2.01 | 0.552 | 0.70 | 0.28–1.77 | 0.448 |

| Male | 1.00 | 0.91–1.11 | 0.965 | 0.89 | 0.81–0.99 | 0.030 | 0.85 | 0.68–1.06 | 0.146 | 0.84 | 0.69–1.02 | 0.076 |

| Marital status (single) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Married | 0.85 | 0.70–1.04 | 0.121 | 0.77 | 0.63–0.93 | 0.008 | 1.19 | 0.77–1.85 | 0.428 | 0.45 | 0.30–0.68 | <0.001 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 0.92 | 0.82–1.03 | 0.144 | 0.98 | 0.87–1.11 | 0.775 | 0.70 | 0.55–0.91 | 0.007 | 0.86 | 0.68–1.07 | 0.181 |

| Living arrangement(independent) | –– | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Living with family | 1.00 | 0.70–1.42 | 0.992 | 0.55 | 0.39–0.77 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.37–1.84 | 0.627 | 0.35 | 0.16–0.80 | 0.013 |

| Homeless or shelter | 0.55 | 0.37–0.83 | 0.004 | 1.05 | 0.67–1.62 | 0.839 | 1.81 | 0.89–3.64 | 0.099 | 1.22 | 0.66–2.26 | 0.532 |

| Residential program | 1.52 | 1.18–1.95 | 0.001 | 2.34 | 1.75–3.13 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 0.82–2.16 | 0.242 | 2.42 | 1.49–3.92 | <0.001 |

| Clinical | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Primary diagnosis (schizophrenia) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Schizoaffective | 1.12 | 1.01–1.23 | 0.027 | 0.97 | 0.88–1.08 | 0.597 | 1.20 | 0.97–1.48 | 0.099 | 0.92 | 0.76–1.11 | 0.379 |

| Co-occurring diagnosis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Substance abuse disorder | 0.65 | 0.55–0.77 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.69–0.99 | 0.042 | 1.20 | 0.87–1.66 | 0.270 | 0.76 | 0.59–0.97 | 0.027 |

| Depressive disorder | 0.80 | 0.69–0.93 | 0.003 | 1.38 | 1.18–1.63 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.34–2.18 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.72–1.09 | 0.261 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.93 | 0.70–1.24 | 0.638 | 1.02 | 0.75–1.38 | 0.901 | 1.14 | 0.66–1.97 | 0.636 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.26 | 0.417 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 | 1.23 | 1.09–1.40 | 0.001 | 1.22 | 1.07–1.38 | 0.003 | 1.36 | 1.06–1.74 | 0.014 | 1.30 | 1.04–1.64 | 0.024 |

| 2 | 1.36 | 1.06–1.76 | 0.017 | 1.08 | 0.84–1.39 | 0.565 | 1.20 | 0.73–1.99 | 0.468 | 0.82 | 0.54–1.25 | 0.349 |

| ≥3 | 1.17 | 0.83–1.66 | 0.373 | 1.33 | 0.92–1.92 | 0.134 | 1.51 | 0.81–2.84 | 0.196 | 1.15 | 0.64–2.08 | 0.635 |

| Prior hospitalization in past year | 1.00 | 0.89–1.13 | 0.985 | 1.48 | 1.31–1.69 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.08–0.14 | <0.001 | 1.45 | 1.22–1.73 | <0.001 |

| Contextual-level factors | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sociodemographics | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Percent African | 0.92 | 0.83–1.01 | 0.095 | 1.05 | 0.95–1.17 | 0.354 | 0.93 | 0.80–1.08 | 0.335 | 0.98 | 0.83–1.17 | 0.858 |

| American | ||||||||||||

| Percent Hispanic | 1.04 | 0.85–1.27 | 0.709 | 1.09 | 0.87–1.35 | 0.467 | 0.92 | 0.72–1.19 | 0.535 | 1.01 | 0.76–1.35 | 0.935 |

| Per capita income, per $10,000 | 1.02 | 0.56–1.87 | 0.947 | 0.94 | 0.49–1.80 | 0.848 | 1.79 | 0.73–4.41 | 0.204 | 0.99 | 0.35–2.80 | 0.984 |

| Percent living in poverty | 0.99 | 0.93–1.06 | 0.854 | 0.96 | 0.90–1.03 | 0.244 | 0.98 | 0.90–1.08 | 0.710 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.03 | 0.137 |

| Percent unemployed | 1.06 | 0.98–1.14 | 0.127 | 1.02 | 0.94–1.10 | 0.660 | 0.98 | 0.83–1.16 | 0.806 | 1.09 | 0.94–1.26 | 0.252 |

| Health care system | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Psychiatrists per 10,000 pop | 0.84 | 0.41–1.73 | 0.642 | 1.12 | 0.51–2.46 | 0.777 | 1.19 | 0.52–2.75 | 0.677 | 1.82 | 0.65–5.11 | 0.257 |

| Psychologists per 10,000 pop | 1.30 | 1.07–1.57 | 0.008 | 1.27 | 1.04–1.55 | 0.021 | 0.88 | 0.59–1.31 | 0.524 | 1.19 | 0.76–1.86 | 0.445 |

| Social workers per 10,000 pop | 1.03 | 0.98–1.09 | 0.282 | 0.94 | 0.88–1.00 | 0.043 | 0.96 | 0.89–1.04 | 0.359 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.081 |

| CMHCc | 1.10 | 0.89–1.36 | 0.362 | 1.10 | 0.86–1.39 | 0.450 | 1.31 | 1.09–1.58 | 0.005 | 1.06 | 0.82–1.38 | 0.660 |

| Rurality: urban influence code (1)d | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.37 | 0.882 | 0.77 | 0.55–1.06 | 0.112 | 1.24 | 0.85–1.80 | 0.259 | 0.81 | 0.52–1.24 | 0.324 |

| 3 | 1.07 | 0.69–1.65 | 0.762 | 0.90 | 0.56–1.44 | 0.660 | 1.08 | 0.54–2.14 | 0.826 | 0.83 | 0.43–1.60 | 0.573 |

| 4 | 0.45 | 0.23–0.90 | 0.024 | 0.78 | 0.37–1.65 | 0.519 | 1.29 | 0.29–5.81 | 0.742 | 1.58 | 0.37–6.63 | 0.535 |

| 5 | 0.88 | 0.57–1.36 | 0.564 | 0.92 | 0.57–1.47 | 0.712 | 1.08 | 0.54–2.16 | 0.830 | 0.60 | 0.30–1.22 | 0.159 |

| 6 | 0.71 | 0.37–1.36 | 0.298 | 0.70 | 0.35–1.39 | 0.303 | 0.17 | 0.02–1.45 | 0.105 | 0.21 | 0.06–0.79 | 0.021 |

| 7, 8, 9, and 10e | 0.58 | 0.32–1.08 | 0.362 | 0.47 | 0.24–0.90 | 0.023 | 0.59 | 0.15–2.39 | 0.461 | 0.24 | 0.07–0.80 | 0.020 |

CI confidence interval

Medication management: χ2 = 180.1, df (32), p < 0.001; outpatient treatment: χ2 = 210.4, df (32), p < 0.001; intensity of aftercare: χ2 = 308.3, df (32), p <0.001; case management: χ2 = 115.1, df (32), p <0.001

Reference categories are in parentheses

Community mental health centers

Most urban

Most rural

Individual-Level Factors

All of the patient demographic and clinical characteristics were significantly associated with continuity of care, except the presence of a co-occurring anxiety disorder. Of the demographic characteristics examined, age, race and ethnicity, marital status, and living arrangement were all significantly associated with three of the continuity of care measures. Gender was only significantly associated with one process measure; males had a 11 % lower odds of receiving outpatient treatment compared to females (OR = 0.89, p = 0.03). Age was consistently positively associated with continuity of care; being older increased the odds of receiving regular outpatient care (medication management, and outpatient treatment, and case management services) by 14, 14, and 22 % (ORs = 1.14, 1.14, and 1.22, all p < 0.001, respectively) for a 10 year increase in age. African American adults had a significantly lower odds of receiving regular outpatient care (ORs = 0.76 and 0.85 for medication management and outpatient care, p < 0.001 and p = 0.006, respectively) and follow-up visits after hospitalization (OR = 0.77, p = 0.028) compared to whites. Married adults with schizophrenia had a 23 % lower odds of receiving regular outpatient treatment and case management services compared to single adults (ORs = 0.77 and 0.45, p = 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively). Divorced or separated adults also had a 30 % lowered odds of receiving regular outpatient follow-up visits after hospitalization (OR = 0.70, p = 0.007) compared to single adults. Living arrangement was also strongly associated with continuity of care; the odds of receiving regular outpatient care (medication management and outpatient visits) and case management were significantly higher for individuals living in residential programs than those living independently (ORs = 1.52, 2.34, and 2.42, p = 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). In contrast, homelessness decreased the odds of receiving regular medication management visits by 45 % (OR = 0.55, p = 0.004). Living with family was also associated with a lowered odds of receiving regular outpatient treatment (OR = 0.55, p < 0.001) and case management (OR = 0.35, p = 0.013).

Of the clinical variables tested, all of the psychiatric and medical comorbidities (except anxiety disorders) and prior hospitalizations were associated with at least three of the four continuity of care measures. The presence of a co-occurring substance abuse disorder significantly lowered the odds of receiving regular medication management (OR = 0.65, p < 0.001), outpatient treatment (OR = 0.83, p = 0.042), and case management services (OR = 0.76, p = 0.027). Having a diagnosis of depression increased the odds of receiving outpatient treatment and follow-up visits after hospitalization by 38 and 71 %, respectively (ORs = 1.38 and 1.71, both p < 0.001, respectively), but decreased the odds of receiving medication management by 20 % (OR = 0.80, p = 0.003). The presence of one chronic medical condition versus none was associated with a higher likelihood of conforming to all four continuity of care outcomes. Prior psychiatric hospitalizations during the past year increased the odds of receiving regular outpatient treatment and case management services (ORs = 1.48 and 1.45, p < 0.001, respectively). Contrary to expectations, individuals with a history of prior hospitalization had a lower odds of receiving regular outpatient follow-up care during the subsequent hospitalization (OR = 0.11, p < 0.001).

Contextual-Level Characteristics

Contextual characteristics examined included sociodemographic and economic characteristics of the county population, health care system characteristics, and the urban–rural influence code. As shown in Table 5, individuals residing in counties with a greater supply of licensed psychologists were significantly more likely to receive regular outpatient care; each additional psychologist per 10,000 population increased the odds of receiving regular medication management visits and outpatient treatment by about 30 % (OR = 1.30, p = 0.008), holding all other variables in the model constant. The number of community mental health centers in the county was also associated with an increased odds of receiving follow-up visits after hospitalizations (OR = 1.31, p = 0.005) per one unit increase in the number of centers. In contrast, rurality was negatively associated with continuity of care. Residence in more rural counties (UIC categories 4, 7, 8, 9, and 10) as compared to the most urban counties (UIC category 1—population >1 million) lowered the odds of receiving medication management, outpatient treatment, and case management services by 55, 53 %, and about 76 %, respectively (ORs = 0.45, 0.47, and 0.24, p < 0.05, p = 0.023, and p = 0.020, respectively).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study examined rates of conformance to continuity of care standards for adults with schizophrenia and identified individual and contextual level factors associated with conformance. A greater understanding of factors associated with continuity of care may help to identify high-risk patients that may benefit most from quality improvement efforts and promote the use of best-practices.

Consistent with prior studies (c.f. Mojtabai et al. 2010), we found that continuity of care for patients with schizophrenia was generally below benchmarks for recommended standards of care, highlighting the need for quality improvement interventions. Rates of conformance ranged from 3.5 to 88 %, with the lowest rates for individuals with co-occurring substance abuse disorders and highest for treatment engagement. Only about two-thirds of adults received regular outpatient care, which barely meets the current minimal standards of care. Other studies have found rates for receipt of outpatient care ranging from 41 to 81 % (Busch et al. 2009; Dickey et al. 2003; Lehman and Steinwachs 1998; West et al. 2005). These rate variations can be attributed to differences in study samples and definitions of outpatient care. Only 15 % of schizophrenic patients received regular outpatient care following hospital discharge, and 64 % received case management services among those who were high users of inpatient and/or emergency services. These rates are significantly lower than those found in previous research with Medicaid populations (Hermann et al. 2006; Olfson et al. 2010). Our findings on the low rates of conformance of adults with co-occurring substance abuse disorders are consistent with prior studies (e.g., Hermann et al. 2006; IOM 2006; West et al. 2005).

Our results confirm that continuity of care is influenced by both individual-level factors and contextual-level factors. Consistent with prior research, younger adults, males, and minorities were less likely to receive adequate continuity of care (Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009). The poorer continuity of care found in younger adults compared to older adults may relate to age differences in beliefs about illness, help-seeking behavior, and developmental differences in coping styles (O'Brien et al. 2009).

We found that African American adults with schizophrenia were less likely to receive regular outpatient care and timely follow-up after hospitalization. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of mental health care is well documented in the research literature (IOM 2002; Fischer et al. 2008; Schraufnagel et al. 2006; Van Voorhees et al. 2007). The reasons for these disparities are complex and multifaceted and include (1) patient factors such as cultural beliefs about illness and treatment; (2) provider factors involving faulty communication stemming from ethnicmismatch between patient and provider; and (3) system factors relating to shortage of providers and lack of insurance (IOM 2002; Schraufnagel et al. 2006; Van Voorhees et al. 2007).

As expected, living arrangement and marital status were statistically associated with continuity of care. Overall, our findings suggest that living situation can be both a source of stress and a protective factor. For example, the findings that adults living in residential treatment centers were over two times more likely to receive adequate continuity of care compared to those living independently highlight the importance of structure, support, and treatment. Conversely, homelessness or living with family was associated with poorer continuity of care. Consistent with prior research, less than half of homeless adults received regular medication management (Folsom and Jeste 2002). The finding that adults living with family were less likely to receive regular outpatient care and case management is contrary to our expectations but may be related to severity of illness. Patients with less severe illness may be more likely to continue to live with family rather than supported housing and may consequently perceive less need for treatment. That nearly two-thirds of adults living with their family did not receive case management is not surprising, as families often assume the role of pseudo-case managers.

Findings regarding marital status are mixed. Contrary to expectations, married adults with schizophrenia were less likely to receive regular outpatient care compared to those who were single. One possible explanation for the lower continuity of care among the married may be combined effects of severity of illness on both the likelihood of marrying and the need for continued treatment; patients with more severe illness tend to have more continuous care but are generally less likely to marry. Finally, the finding that those who were divorced, separated or widowed were less likely to receive follow-up care after hospitalization is consistent with prior research suggesting that this group is at high risk for treatment drop out (Nyer et al. 2010). Taken together, our results underscore the need for ongoing assessment and monitoring of patients' living arrangement and social circumstances.

In addition, clinical factors including comorbidities and prior service history were significantly associated with continuity of care. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Busch et al. 2009; Olfson et al. 2010; Stein et al. 2007), the presence of a co-occurring substance abuse disorder increased the risk for poor continuity of care, a relationship which persisted across multiple measures of continuity. It is estimated that nearly one half of persons with schizophrenia have comorbid substance abuse disorders (APA 2004a), which greatly complicate treatment and are associated with more frequent and longer hospitalizations, more pronounced psychotic symptoms, and other negative outcomes (Dickey and Azeni 1996; Drake et al. 1990; Haywood et al. 1995; Cuffel et al. 1994; Rosenberg et al. 2001). Moreover, substance abusers are often difficult to engage in treatment and non-adherent with medications.

The finding that adults with co-occurring depressive disorders were more likely to receive regular follow-up after hospitalization and continuity of outpatient care was expected, given the association between depressive symptoms and suicide and the especially high rates of suicide among persons with schizophrenia (Black and Fisher 1992; Simpson and Tsuang 1996). Clinicians and treatment teams may take special care to ensure continuity of care for adults with depressive symptoms not only to assess suicide risk but to monitor worsening depression and response to treatment, especially in view of current APA guidelines (2003) recommending higher frequency of visits after hospitalization due to the increased risk of suicide post discharge.

Similarly, greater medical comorbidity and prior psychiatric hospitalizations—both indicators of clinical need—were associated with better continuity of care. One reason for the higher continuity of care among persons with schizophrenia with medical comorbidities is that they may have greater contact with more health professionals (Wang et al. 2000). Prior hospitalizations are also a proxy for severity of illness and a risk factor for relapse which may signal the need for greater continuity of care by providers (Young et al. 1999). Patients with prior hospitalizations may also perceive a greater need for treatment; thus they tend to show up more regularly and be more compliant with treatment.

Our results add to the growing body of literature emphasizing the influence of community-level factors on access to mental health care. Consistent with the study by Hendryx et al. (1995), we found that greater service availability was associated with better continuity of care for adults with schizophrenia. Individuals living in areas with higher levels of mental health professionals were more likely to receive regular outpatient care. Similarly, individuals living in areas with more community mental health centers had better outpatient follow-up after hospitalization.

In contrast, residence in a rural area was negatively associated with continuity of care. Three sets of barriers impede access to care for rural residents: (1) low supply of providers; (2) longer travel distances to obtain care; and (3) cultural beliefs among rural residents, notably a preference to rely on extended family and friends (Mayer et al. 2005; Reschovsky and Staiti 2005). Taken together, our results confirm previous research suggesting that access to mental health is influenced by geographic accessibility and provider availability.

Limitations

The strengths of our study relate to the use of Medicaid claims data which provides population-based assessment of quality of care and detailed longitudinal information on service utilization patterns including diagnoses, treatments, and clinical encounters across a range of health care settings. Such detailed longitudinal histories can be used to identify and target clients at risk for poor outcomes. In addition, the merging of Medicaid data with other data sources also allowed for multilevel analyses of individual and contextual-level factors, often overlooked by previous investigators.

Several limitations need to be considered, however. First, because we analyzed data from one state Medicaid program, study findings may not be generalizable to other state Medicaid programs or to privately insured or uninsured populations. However, the consistency of our results with other studies using Medicaid data suggests that findings may be broadly relevant to all Medicaid programs. Second, because the study relied on administrative data we were limited to visit-based measures of continuity of care. Thus, we were not able to assess other important dimensions of continuity of care identified in the literature such as level of communication across service systems and provider and consistency of providers. Another related issue involves the validity of the continuity of care measures. While our measures had high face validity, the majority were based on consensus opinion or lower level of evidence rather than empirical evidence. Unfortunately, quality of care research in mental health is still in the early developmental phases. Also, these measures reflect only a maintenance level of treatment for schizophrenia and may not be adequate for significant functional or clinical change to occur. Still, the frequency and intensity of treatment needed to produce change is unknown, Third, our use of claims data precluded an examination of other important factors that may influence continuity of care such as the quality of outpatient care provided to patients, organizational and provider characteristics, family involvement and social support network, and other patient factors. Nevertheless, we attempted to minimize selection bias by controlling for a wide array of demographic, clinical, and community-level factors. Finally, since no outcome data were available, we were unable to examine the impact of varying levels of continuity of care on client outcomes.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our results suggest several directions for clinical and policy interventions aimed at improving continuity of care for adults with schizophrenia. First, the findings underscore the need to target interventions to high-risk patient groups and high-risk time periods. Targeted interventions are advantageous because they allow for matching of treatments to client needs and allocation of resources to those most in need and at critical time periods (Mojtabai et al. 2003). We identified three patient groups at particularly high risk for poor continuity of care: individuals with co-occurring substance abuse disorders, individuals with early onset psychosis, and individuals from ethnic and minority backgrounds. For dual diagnosed individuals, integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment approaches have been shown to be effective in increasing program retention and engagement in treatment (Hellerstein et al. 1995; Herman et al. 1987). These treatments, typically delivered by multidisciplinary teams, emphasize outreach and engagement, comprehensive services, and a stage-wise approach to treatment (Drake and Mueser 2002). Less is known about effective treatments for younger, newly diagnosed adults with psychotic illness. However, an emerging body of research indicates that early interventions service models that include ACT, intensive supports, and evidence-based interventions can improve short-term outcomes (Singh and Fisher 2005). For minority persons, the most effective approaches are multi-component interventions and culturally-tailored interventions (Van Voorhees et al. 2007; Wagner et al. 1996). Finally, study findings highlight the need for critical time interventions that target the posthospitalization transition period where discontinuity of care is common and the risks for adverse outcomes are high (Dixon et al. 2009).

Second, our results suggest the need to address community-level structural factors that impede access to care. Ensuring an adequate supply of health resources is challenging, especially in rural communities, yet critical for improving access and continuity of care (Goldman et al. 2001). To effectively address these issues, policy makers should: (1) support adequate funding of mental health and substance abuse services; (2) expand safety net programs which serve a disproportionate number of low-income individuals (Institute of Medicine (U.S.) 2003); and (3) encourage and incentivize strategies to recruit and retain mental health professionals. The Affordable Care Act offers the opportunity to address several of these needs as well as improve continuity of care (Mechanic 2012). Moreover, the Health Professional Shortage Area Program provides incentives to recruit mental health professionals to work in underserved areas (Pathman et al. 2004). For rural residents, intervention approaches, such as the use of telepsychiatry and integrated mental health and primary care models, have shown promise in improving access to care (Rost et al. 2002).

Conclusions

In sum, our findings suggest that a substantial proportion of people with schizophrenia are receiving less than adequate continuity of care, highlighting the need for quality improvement initiatives. Both individual and community-level factors were associated with variations in continuity of care. Systematic quality improvement initiatives are needed that target structural aspects of care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants from the National Center for Research Resources (UL1RR025755) and a faculty development Grant from the Ohio State College of Social Work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

An early version of this paper was presented at the 2nd Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference, Florence, Italy, April 10–14, 2010.

References

- Adair CE, McDougall GM, Beckie A, Joyce A, Mitton C, Wild CT, et al. History and measurement of continuity of care in mental health services and evidence of its role in outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(10):1351–1356. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(Nov suppl):1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. 2nd. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2004a. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Compendium 2004. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G, Knickman JR. Changing the chronic care system to meet people's needs. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):146–160. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach LL. Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138(11):1449–1456. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.11.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoli GJ, Kang R, Hasnain-Wynia R, Lindrooth RC. An update on safety-net hospitals: Coping with the late 1990s and early 2000s. Health Affairs. 2005;24(4):1047–1056. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Fisher R. Mortality in DSM-IIIR schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 1992;7(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90040-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Test MA. A model for measuring the implementation of community support programs: results from three sites. Community Mental Health Journal. 1992;28(3):227–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00756819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(2):383–402. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, White S, Clement S, Ellis G, Jones IR, et al. Continuity of care in mental health: Understanding and measuring a complex phenomenon. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(2):313–323. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman H, Frank RG. Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Medical Care. 2009;47(2):199–207. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818475b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MJ, de Jonge E, Freeman GK, Weaver T. Providing continuity of care for people with severe mental illness: A narrative review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39(4):265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0732-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffel BJ, Shumway M, Chouljian TL, MacDonald T. A longitudinal study of substance use and community violence in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182(12):704–708. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PJ, Bazzoli GJ, Katz A. Caught in the competitive crossfire: Safety-net providers balance margin and mission in a profit-driven health care market. Health Affairs. 2008;27(5):374–382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.w374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PL, Andersen RM, Wyn R, Brown ER. A framework for evaluating safety-net and other community-level factors on access for low-income populations. Inquiry. 2004;41(1):21–38. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Azeni H. Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: Their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(7):973–977. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Normand SL, Hermann RC, Eisen SV, Cortes DE, Cleary PD, et al. Guideline recommendations for treatment of schizophrenia: The impact of managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(4):340–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Goldberg R, Iannone V, Lucksted A, Borown C, Kreyenbuhl J, et al. Use of a critical time intervention to promote continuity of care after psychiatric inpatient hospitalization. Psychiatric Service. 2009;60(4):451–458. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment: Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake R, Mueser KT. Co-occurring alcohol use disorder and schizophrenia. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26(2):99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Drake R, Osher F, Noordsy D, Hurlbut S, Teague G, Beaudett M. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16(1):57–67. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, McCarthy J, Ignacio R, Blow F, Barry K, Hudson T, et al. Longitudinal patterns of health system retention among veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44(5):321–330. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom D, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia inhomeless persons: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105(6):404–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney J, Sullivan G, Williams K, Jackson C, Morton SC, Koegel P. Measuring continuity of care for clients of public mental health systems. Health Services Research. 2003;38(4):1157–1175. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Xu S, Dong F. Community-level correlates of hospitalizations for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(6):772–778. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs VR. Perspective: More variation in use of care, more flat-of-the-curve medicine. Health Affairs. 2004;(Variation):104–107. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber S, Dougherty RH. Disease management for chronic behavioral health and substance use disorders. 2005 Retrieved May 20, 2006 from http://www.chcs.org/usr_doc/bh_dm.pdf.

- Goldman H, Ganju V, Drake RE, Gorman P, Hogan M, Hyde M, et al. Policy implications for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1591–1597. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA, Fontana A. Continuity of care and clinical effectiveness: treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2003;30(2):202–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02289808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresenz CR, Stockdale SE, Wells KB. Community effects on access to behavioral health care. Health Services Research. 2000;35(1):293–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, Cavanaugh JL, Jr, Davis JM, Lewis DA. Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):856–861. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstein DJ, Rosenthal RN, Miner CR. A prospective study of integrated substance-abusing schizophrenic patients. American Journal on Addictions. 1995;4(1):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hendryx MS, Rohland BM. A small area analysis of psychiatric hospitalizations to general hospitals: Effects of community mental health centers. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1994;16(5):313–318. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendryx MS, Urdaneta ME, Borders T. The relationship between supply and hospitalization rates for mental illness and substance use disorders. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1995;22(2):167–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02518756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman SE, BootsMiller B, Jordan L, Mowbray CT, Brown WG, Deiz N, et al. Immediate outcomes of substance abuse treatment within a state psychiatric hospital. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1987;24(2):126–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02898508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann RC, Chan JA, Provost SE, Chiu WT. Statistical benchmarks for process measures of quality of care for mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(10):1461–1467. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann RC, Finnerty M, Provost S, Palmer RH, Chan J, Lagodmos G, et al. Process measures for the assessment and improvement of quality of care for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2002;28(1):95–104. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann RC, Palmer RH. Common ground: A framework for selecting core quality measures for mental health and substance abuse care. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(3):281–287. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (U.S.) Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (U.S.) A shared destiny: Community effects of uninsurance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) (U.S.) Improving the quality of health care for mental health and substance abuse conditions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Prosser D, Bindman J, Szmukler G. Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: Concepts and measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1997;32(3):137–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00794612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce AS, Wild TC, Adair CE, McDougall GM, Gordon A, Costigan N, et al. Continuity of care in mental health services: Toward clarifying the construct. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;49(8):539–550. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36(6):987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: A review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(4):696–703. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno E, Rothbard AB. Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):567–572. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D, Agger M. Access of rural Medicaid beneficiaries to mental health services. Health Care Financing Review. 1995;17(1):133–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D, Agger M, Hartley D. Service use of rural and urban Medicaid beneficiaries suffering from depression: The role of supply. Journal of Rural Health. 1999;15(3):344–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: Initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24(1):11–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litaker D, Love TE. Health care resource allocation and individuals' health care needs: Examining the degree of fit. Health Policy. 2005;73(2):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M, Slifkin R, Skinner AC. The effects of rural residence and other social vulnerabilitiesonsubjective measures of unmet need. Medical Care Research and Review. 2005;62(5):617–628. doi: 10.1177/1077558705279315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Norquist GS, Wells KB, Sullivan G, Liberman RP. Quality-of-care research in mental health: Responding to the challenge. Inquiry. 1988;25(1):157–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Seizing opportunities under the Affordable Care Act for transforming the mental and behavioral health system. Health Affairs. 2012;31(2):376–382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Fochtmann L, Kotov R, Chang S, Craig TJ, Bromet E. Patterns of mental health service use and unmet needs for care in individuals with schizophrenia in the US. US Psychiatry. 2010;3:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Malaspina D, Susser E. The concept of population prevention: Application to schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(4):791–801. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyer M, Kasckow J, Fellows I, Lawrence EC, Golshan S, Solorzano E, et al. The relationship of marital status and clinical characteristics in middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia and depressive symptoms. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A, Fahmy R, Singh SP. Disengagement from mental health services: A literature review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44(7):558–568. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Doshi JA. Continuity of care after inpatient discharge of patients with schizophrenia in the medicaid program: A retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):831–838. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m05969yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Taylor DH, Koch G. Outcomes of states' scholarships, loan repayment, and related programs for physicians. Medical Care. 2004;42(6):560–568. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128003.81622.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly MV, Paga′n JA. Spillovers and vulnerability: The case of community uninsurance. Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):1304–1313. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: Assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Services Research. 1998;33(3):571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality Resource Systems. Health resources and services administration Bureau of health professions Area resource file(ARF) system. Fairfax, VA: Quality Resource Systems; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reschovsky JD, Staiti AB. Access and quality: Does rural America lag behind? Health Affairs. 2005;24(4):1128–1139. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA. Socioeconomic position and health: The independent contribution of community socioeconomic context. Annual Review of Sociology. 1999;25(1):489–516. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(1):31–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, Smith K. Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: The rural perspective. Medical Care Research and Review. 2002;59(3):231–265. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, Nixon CT, Schut LJ, Karver MS, Bickman L. Validating quality indicators: Quality as relationship between structure, process, and outcome. Evaluation Review. 1997;21(3):292–309. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9702100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne PP. Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: What does the evidence tell us? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JC, Tsuang MT. Mortality among patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22(3):485–499. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Fisher HL. Early intervention in psychosis: Obstacles and opportunities. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11(1):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Kogan JN, Sorbero MJ, Thompson W, Hutchinson SL. Predictors of timely follow-up care among medicaid-enrolled adults after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Test MA. Continuity of care in community treatment. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1979;2:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Walters AE, Prochaska M, Quinn M. Reducing health disparities in depressive disorders outcomes between non-hispanic whites and ethnic minorities. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5):157S–194S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]