Abstract

Background

Prior research suggests an important role of systemic inflammation in pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation (AF). It is well-known that rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic, systemic inflammatory disorder, increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but little evidence exists whether the risk of AF is increased in RA.

Methods

Using data from a large US commercial insurance plan, we examined the incidence rate (IR) of hospitalization for AF in patients with RA compared to non-RA. RA patients were identified with ≥ 2 separate visits coded for RA and ≥ 1 disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug dispensing. The IR of AF in RA patients was also compared to those with osteoarthritis, a chronic non-inflammatory condition.

Results

There were 20,852 RA and 104,260 non-RA patients, matched on age, sex and index date. The mean follow-up was 2 years. The IR per 1,000 person-years of AF was 4.0 (95% CI, 3.4–4.7) in RA and 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6–3.0) in non-RA patients. The incidence rate ratio for AF was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2–1.7) in RA compared to non-RA patients. In a multivariable Cox model adjusting for a number of risk factors such as diabetes, CVD, medications and health care utilization, the risk of AF was no longer increased in RA (hazard ratio 1.1, 95% CI: 0.9–1.4) compared to non-RA patients. There was also no difference in the AF risk between RA and osteoarthritis patients.

Conclusion

Our results show no increased risk of AF associated with RA, after adjusting for various comorbidities, medications and health care use.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

The link between systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as myocardial infarction (MI) and coronary artery disease has been well-established.[1, 2] Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia and strongly related to CVD.[3] Previous research suggests a potential role of inflammation in the development and maintenance of AF.[4] Several epidemiologic studies show a significant association between serum inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-2, IL-6, and c-reactive protein (CRP) and the risk of AF development, recurrence or persistence.[4–6] The link between inflammatory markers and AF seems clearest among patients with inflammatory cardiac conditions, such as pericarditis or myocarditis, but several large prospective cohort studies also found an association between systemic inflammation and incident AF even after controlling for traditional risk factors for CVD.[7, 8]

It is well known that patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have an increased risk of CVD including stroke.[9–12] AF is the most common arrhythmia associated with an increased risk of stroke[13] and RA patients have a significantly greater risk of cardiac involvement including valvular nodules and valvular heart diseases which are known risk factors of AF.[14]

If systemic inflammation is one of the causes of AF, patients with chronic inflammatory conditions such as RA may have an increased risk of AF. To date, little data is available whether RA is associated with the risk of AF. A recently published Danish cohort study noted a 40% increase in the risk of AF in patients with RA compared to the general population.[15] We hypothesized that RA patients would have a greater risk of developing AF compared to non-RA patients after controlling for known CVD risk factors. The main objective of this study was to assess the rate of incident AF in a cohort of RA patients compared to those without RA in a large population-based cohort study.

METHODS

Data Source

We conducted a cohort study using the claims data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database, a commercial U.S. health plan ( January 1, 2001-June 30, 2008). This database contains longitudinal claims information including medical diagnoses, procedures, hospitalizations, physician visits, and pharmacy dispensing on more than 28 million fully-insured subscribers, with medical and pharmacy coverage across the U.S. Personal identifiers were removed from the dataset before the analysis to protect subject confidentiality. Patient informed consent was therefore not required. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Study Cohort

Adults who had at least two visits, separated by at least seven days, coded for RA with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD 9) code, 714.xx were eligible for the RA cohort. The index date for the RA cohort was defined as the date of first disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) dispensing after at least 12 months of continuous health plan eligibility; thus, all persons in the RA cohort were required to have had two diagnoses and at least one filled prescription for a DMARD at the start of follow-up. Nursing home residents or patients who underwent cardiac surgeries in the 12-month period prior to index dates were excluded. To ensure that we only include incident cases of AF, subjects with a diagnosis of any arrhythmia, dispensings for anticoagulants or anti-arrhythmic drugs in the 12-month period prior to index dates were also excluded from both cohorts. (Additional Table 1) A previous validation study showed that RA patients can be accurately identified using a combination of diagnosis codes and DMARD prescriptions in insurance claims data.[16]

We identified two non-RA cohorts over age 18 for comparison. The first comparison cohort, described herein as the “non-RA cohort” consisted of patients who never had a diagnosis of RA during the study period and had at least 2 physician visits after at least 12 months of continuous health plan eligibility. The index date for the non-RA patients began at the first receipt of any prescription drugs after at least 2 physician visits. The aforementioned exclusion criteria were then applied to the non-RA cohort. The non-RA patients were matched to RA patients on age, sex and index date (+/− 30 days) with a 5:1 ratio.

To compare the risk of AF in RA patients with persons who have another chronic debilitating condition that requires regular visits to a physician but is non-inflammatory, we identified a second comparison cohort, ‘the osteoarthritis (OA) cohort’. It was defined based on at least two visits coded for OA using the ICD-9 code (715.xx). The index date for the OA cohort was the date of 1st receipt of prescription for NSAIDs including selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or opioids after the 2nd visits for osteoarthritis. The same aforementioned exclusion criteria were applied to the OA cohort. Patients with OA were then matched to RA patients on age, sex and index date (+/− 30 days) with a 1:1 ratio.

Patients in all three cohorts were followed from the index date to the first of any of the following censoring events: development of AF, loss of health plan eligibility, end of study database, or death.

Outcome Definition

The primary outcome was defined as a hospitalization for AF based on hospital discharge diagnosis codes (ICD-9: 427.31) within the study database. This algorithm has been previously validated and had both sensitivity and specificity greater than 90%.[17]

Two secondary more stringent AF outcomes were defined. One outcome required a combination of a hospital discharge diagnosis of AF and a prescription for an anticoagulant within 30 days after discharge date. Another secondary outcome required a diagnosis of AF or atrial flutter (ICD-9: 427.3x) from either outpatient or inpatient claims and a prescription for an anticoagulant within 30 days after discharge or outpatient diagnosis date.

Covariates

A number of predefined variables potentially related to development of AF and health care use were assessed using data from the 12 months before the index date. These variables included demographic factors, comorbidities such as hypertension, CVD, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), medications, and health care utilization factors., A combined comorbidity score was calculated to quantify patients’ comorbidities based on ICD codes.[18] Outpatient laboratory data such as acute phase reactants (APR) (i.e., ESR or CRP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) were available in a subgroup of all three study cohorts.

Statistical Analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics between RA and non-RA cohorts. For the primary outcome, we estimated the crude and age-stratified IR of a hospitalization for AF, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), calculated as the number of patients with the outcome divided by the total person-time, in both RA and non-RA cohorts. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) with 95% CI was estimated by dividing the rate of a hospitalization for AF among RA patients by that of non-RA cohorts.[19] Assuming an incidence of AF would be 4 per 1,000 in non-RA cohort and there are at least 20,000 subjects with RA, at least 80% power to detect a risk ratio of 1.4 or higher was expected. To adjust for potential confounders, separate Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare the rate of a hospitalization for AF among RA patients with those in non-RA cohorts.[20] Similar analyses were carried out for the secondary AF outcomes. All the analyses were then repeated for the comparison between patients with RA and OA.

Finally, we conducted subgroup analyses for the primary outcome in patients in whom we had APR and RF measurements at baseline. Among these subjects, the APR levels were used as a binary covariate, elevated vs. normal, in Cox proportional hazard models comparing the risk of a hospitalization for AF in RA with non-RA. We also examined whether an elevated APR level and/or a positive RF at baseline increased the risk of a hospitalization for AF among RA patients. All analyses were done using SAS 9.2 Statistical Software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Cohort Selection

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected 5 non-RA patients matched to each RA patient on age, sex, and index date. Our final study cohort included 20,852 RA patients and 104,260 non-RA patients. The mean (SD) follow-up time was 2.0 (1.5) years for both RA and non-RA patients. (see Additional Figure 1 for the cohort selection.)

For the secondary analyses comparing RA to OA cohorts, 10,860 OA patients matched on age, sex, and index date to RA patients with a 1:1 ratio were included (Additional Table 2).

Patient Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the age-, sex-, and index date-matched RA and non-RA cohorts were compared (Table 1). The mean age was 52 years and 74% were women in both cohorts. Substantial differences across almost all other baseline characteristics were observed between the cohorts, with the prevalence of comorbidities that may be related to AF risks more common in RA patients than non-RA subjects. Fifteen percent of RA patients and 1% of non-RA patients had their baseline APR levels measured. Thirty-six percent of RA and 18% of non-RA patients with a baseline APR level measurement available had elevated levels. Baseline characteristics of the RA and OA cohorts were similar with the mean age of 56 years and 76% female (Additional Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort in 12 months prior to the index date

| Rheumatoid arthritis (N=20,852) | Non-rheumatoid arthritis (N=104,260) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) or mean ± standard deviation | ||

| Follow-up period, years | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Demographic | ||

|

| ||

| Age*, years | 51.9 ± 12.1 | 51.9 ± 12.1 |

| Female* | 15,497 (74) | 77,485 (74) |

|

| ||

| Comorbidities | ||

|

| ||

| Combined comorbidity score | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 0.9 |

| Diabetes | 1,935 (9) | 9,279 (9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 262 (1) | 647 (1) |

| Liver disease | 558 (3) | 1,900 (2) |

| Hypertension | 5,876 (28) | 26,360 (25) |

| Cardiovascular disease a | 1,439 (7) | 5,355 (5) |

| Valvular or congenital heart disease | 716 (3) | 2,666 (3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2,389 (11) | 8,165 (8) |

| Stroke | 497 (2) | 1,983 (2) |

| Thyroid disease | 3,044 (15) | 11,774 (11) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6,439 (31) | 34,561 (33) |

| Surgery, non-cardiovascular | 184 (1) | 450 (0.4) |

|

| ||

| Medications | ||

|

| ||

| Diuretics | 3,548 (17) | 9,960 (10) |

| ACEI/ARB | 4,087 (20) | 16,203 (16) |

| Bisphosphonates | 2,460 (12) | 4,758 (5) |

| NSAIDs | 12,999 (62) | 16,545 (16) |

| Opioids | 9,155 (44) | 22,206 (21) |

| Beta-blockers | 2,762 (13) | 10,678 (10) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 1,537 (7) | 5,266 (5) |

| Glucocorticoids b | 6,449 (31) | 1,536 (1) |

|

| ||

| Health care utilization | ||

|

| ||

| No. of total physician visits | 10.2 ± 7.4 | 4.9 ± 4.7 |

| No. of hospitalizations | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.5 |

| No. of prescription drug | 9.8 ± 6.0 | 4.5 ± 4.5 |

|

| ||

| Laboratory data | ||

|

| ||

| APR levels available | 3,139 (15) | 1,126 (1) |

| Elevated APR levels c | 1,117 (36) | 200 (18) |

| Rheumatoid factor available | 2,298 (11) | 328 (0.3) |

| Positive rheumatoid factor c | 1,294 (56) | 19 (6) |

matched

includes myocardial infarcts, angina, coronary artery disease, heart failure and cardiomyopathy

use of glucocorticoids 30 days prior to the index date

the proportion was calculated among the subjects with APR or RF levels available

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker, APR: acute phase reactant

Risk of Atrial Fibrillation in RA vs. non-RA

During the follow-up, 0.6% of the study population experienced a hospitalization for AF, the primary outcome of interest. As shown in Table 2, the IR of a hospitalization for AF per 1,000 person-years among RA patients was 4.0, compared with 2.8 in non-RA. The age-stratified IRs of hospitalization for AF are presented in Table 3. The IR was the highest among patients aged 70 years and older in both RA (27.0 per 1,000 person-years) and non-RA cohorts (16.9 per 1,000 person-years). The IRR ranged from 1.3 in patients aged 18 to 49 years to 1.6 in those aged 60 years and older. Cox regression analysis showed that the crude HR of a hospitalization for AF in RA was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2–1.7) and age- and sex-adjusted HR was 1.5 (95% CI, 1.2–1.8) compared to non-RA. After adjusting for potential confounders of AF such as demographic factors, various comorbidities and medications, and health care utilization characteristics listed in Table 1, the risk of AF was no longer increased in RA (HR 1.1, 95% CI, 0.9–1.4) compared to non-RA patients (Additional Table 3). In a fully adjusted Cox model, age-stratified HRs were not significantly increased across any age group (data not shown).

Table 2.

Incidence rates (per 1,000 person-years) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) of atrial fibrillation (AF)

| Outcome definition | Rheumatoid arthritis (N=20,852) | Non-rheumatoid arthritis (N=104,260) | IRR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n) | Person-years, mean (SD) | Rates (95% CI) | Cases (n) | Person-years, mean (SD) | Rates (95% CI) | ||

| AF (inpatient) | 160 | 1.93 (1.5) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) | 574 | 2 (1.6) | 2.8 (2.6–3.0) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| AF (inpatient) and anticoagulants * | 77 | 1.93 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | 297 | 2 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) |

| AF (inpatient and outpatient) and anticoagulants * | 114 | 1.93 (1.5) | 2.8 (2.4–3.4) | 511 | 2 (1.6) | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

CI: confidence interval, SD: standard deviation

: a dispensing of anticoagulants within 30 days after the diagnosis date

Table 3.

Age-stratified incidence rates (per 1,000 person-years) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) of a hospitalization for atrial fibrillation

| Rheumatoid arthritis (N=20,852) | Non-rheumatoid arthritis (N=104,260) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | N | Cases (n) | Person-years, mean (SD) | Rates (95% CI) | N | Cases (n) | Person-years, mean (SD) | Rates (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) |

| 18–49 | 8,371 | 8 | 2.0 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.3–1) | 41,855 | 31 | 2.0 (1.6) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) |

| 50–59 | 7,132 | 35 | 2.1 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 35,660 | 144 | 2.1 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.7–2.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) |

| 60–69 | 3,973 | 54 | 1.7 (1.4) | 8.0 (6.1–10.4) | 19,865 | 179 | 1.8 (1.4) | 5.1 (4.4–5.9) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) |

| 70 and older | 1,376 | 63 | 1.7 (1.5) | 27.0 (21.1–34.5) | 6,880 | 220 | 1.9 (1.6) | 16.9 (14.8–19.3) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) |

CI: confidence interval, SD: standard deviation

For the secondary outcome of a hospitalization for AF combined with a dispensing for an anticoagulant within 30 days from the discharge date, the age and sex-adjusted IRR of AF was 1.3 (95 % CI, 1.0–1.7) in RA compared to non-RA. For the other secondary outcome that combined either inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of AF with a dispensing for an anticoagulant, the age and sex-adjusted IRR was 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9–1.4) in RA compared to non-RA patients. Results from the fully adjusted Cox models for the secondary outcomes were similar to those of the primary outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Fully adjusted* hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for AF in rheumatoid arthritis compared to non-rheumatoid arthritis

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |

|---|---|

| AF (inpatient) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| AF (inpatient) and anticoagulants** | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| AF (inpatient and outpatient) and anticoagulants** | 0.9 (0.8–1.3) |

Adjusted for age, sex, Comorbidity Index, various comorbid conditions, medications, and health care utilization factors listed in Table 1

A dispensing of anticoagulants within 30 days after the AF diagnosis date

Risk of Atrial Fibrillation in RA vs. OA

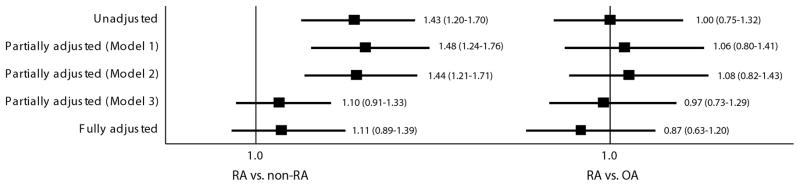

The IRs (5.8 per 1,000 person-years) of AF were similar in both groups with IRR of 1.0 (95% CI, 0.8–1.3). Crude, partially and fully adjusted Cox models consistently showed no increased risk of AF in RA compared to OA patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for a hospitalization for atrial fibrillation.

RA: rheumatoid arthritis, OA: osteoarthritis

Model 1 is adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 is adjusted for age, sex, and cardiovascular disease. Model 3 is adjusted for age, sex, combined comorbidity score and a number of prescription drugs

Subgroup Analyses on Laboratory Data

In a subgroup of patients with the baseline APR levels, the multivariable HR further adjusted for elevated APR levels was 0.6 (95% CI 0.1–2.7) due the small number of events in this subgroup. Among the RA patients with the baseline APR and RF available, multivariable Cox models adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity score and a number of prescription drugs showed an increased risk of AF, albeit not statistically significant, associated with both elevated APR levels (HR 2.2, 95% CI 0.2–20.6) and RF(HR 2.2, 95% CI 0.3–13.9).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the IR of a hospitalization for AF per 1,000 person-years was 4.0 among RA patients and 2.8 in non-RA patients. Although the age-, sex-, and index date-matched IR of a hospitalization for AF was 1.4 times higher in RA compared to non-RA, the fully adjusted regression analyses accounting for various comorbidities, medications, and health care utilization did not show an increased risk of AF in RA. As expected, the IR of a hospitalization for AF increased with age and was highest among patients aged 70 years and older in both groups. After adjusting for all the potential confounders, no significantly increased risk of a hospitalization for AF associated with RA was found across any age groups. Furthermore, consistent null association was noted between inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of AF and RA in multivariable analyses.

If systemic inflammation plays an important role in pathogenesis of AF development,[4, 5, 21] why was no increased risk observed for AF in RA, a disease characterized by chronic systemic inflammation? Several explanations might be plausible for the negative results in this study. First, the negative findings of the present study may be true. While there are a number of prior studies supporting a causal association between inflammation and AF,[4, 5, 21] this association has not been observed in some studies.[8, 22] Moreover, a recent cohort study found an independent association between CRP and AF risk in men but not in women; since RA is more common in women, this also supports our null results.[23] Second, the negative findings could be related to our selection criteria of RA cohort requiring at least one dispensing for a DMARD before entering the study cohort. Although it is clinically unlikely, the level of systemic inflammation in our RA cohort might have been low since all the RA patients in our study received treatment with DMARDs. Third, it is possible that RA has a causal association with AF, but only indirectly through other intermediate factors such as CVD and use of certain medications like NSAIDs or glucocorticoids.[24, 25] By adjusting for many covariates simultaneously in our analyses, we could have removed all the potential effects of RA on AF.

Several strengths of this study are noteworthy. First, we examined a large cohort of RA and non-RA patients in a population that is representative of the U.S. commercially-insured population. Second, to minimize surveillance bias, we selected a group of patients with OA, a chronic non-inflammatory medical condition requiring pharmacologic treatment. Both main and sensitivity analyses consistently showed no increased risk of AF associated with RA. Third, we relied primarily on diagnosis codes for RA and AF, which could potentially lead to exposure and outcome misclassification; however, both the ICD codes for RA and AF have been validated and used in a number of studies. [16, 17] Similar results were also observed in the analysis of secondary outcomes strictly defined with a combination of diagnosis codes and a dispensing of anticoagulants after hospital discharge. Additionally, the IRs and age- and sex-adjusted IRR of AF in this study were similar to the results from a recent Danish population-based study.[15] Fourth, we conducted subgroup analyses of patients with baseline CRP or ESR levels measured, and these yielded consistent results between the RA and non-RA cohorts.

Important differences exist between our results and the prior Danish study that observed an elevated risk of AF in patients with RA.[15] In our study, the multivariable overall and age-stratified HRs of AF, adjusted for health care utilization patterns, concomitant drug uses and comorbidities, were not increased for RA compared to non-RA (Figure 1). On the contrary, the Danish study showed a 40% greater risk of AF in RA compared to non-RA, even after adjusting for cardiovascular drug use and comorbidities. Much of the AF risk attributable to RA was observed in younger and not older patients in the Danish study. These discrepant findings could be due to a number of differences between the two studies. Compared to the Danish cohort, our cohort was younger, had a higher proportion of women and a shorter duration of follow-up time. In addition, there were a greater proportion of subjects with comorbidities such as hypertension, CVD, COPD, and thyroid disease and with more frequent use of cardiovascular drugs in our study cohort. This difference in comorbidity distribution could be simply due to the difference in the study populations, but it could be due to the difference in identifying the comorbidities in the databases. We used a comprehensive algorithm that used a broad category of diagnosis codes combined with the use of comorbidity specific drugs. Furthermore, our study was adjusted for more comorbidities and use of other drugs such as opioids, bisphosphonates, and NSAIDs. Lastly, because we excluded subjects with any diagnosis of arrhythmia, any previous cardiac surgeries, and use of anticoagulants or anti-arrhythmics at baseline, our study might have preferentially included patients at low risk of AF.

Our study also has several limitations. First, this cohort study is likely subject to residual confounding by body mass index, RA disease severity and other unmeasured risk factors including the degree of left ventricular hypertrophy and severity of heart failure or COPD.[3, 13] Second, we assessed a number of variables potentially related to developing AF using the data from the 12 months prior to the index date, but this time period might not be long enough to capture all the information on potential confounders. However, we used multivariable Cox models that simultaneously adjusted for a number of known risk factors of AF, the combined comorbidity score and health care utilization patterns to minimize the effect of such confounders and performed age-stratified Cox analyses. Lastly, a potential role of glucocorticoids or DMARDs including TNF-α inhibitors in the risk of incident AF among RA patients was not examined in this study.

In conclusion, our results showed that incident AF was uncommon in both RA and non-RA patients and there was no increased risk of incident AF associated with RA after multivariable adjustment. The study of the epidemiology of AF in patients with systemic inflammation may provide important insights for AF prevention. Already, a large multicenter clinical trial has been initiated testing the value of inflammation reduction among patients at high risk for AF.[26, 27]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Kim is supported by the NIH grant K23 AR059677. Solomon is supported by the NIH grants K24 AR055989, P60 AR047782, R21 DE018750, and R01 AR056215.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- APR

acute phase reactant

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRP

c - reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DMARD

disease-modifying antirheumatic drug

- ESR

erythrocytes sedimentation rate

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IL

interleukin

- IR

incidence rate

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- OA

osteoarthritis

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- SD

standard deviation

- TNF

tumor-necrosis factor

Footnotes

Kim is supported by the NIH grant K23 AR059677. She received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America and Pfizer and tuition support for the Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard School of Public Health funded by Pfizer and Asisa.

Solomon is supported by the NIH grants K24 AR055989, P60 AR047782, R21 DE018750, and R01 AR056215. Solomon has received salary support through research grants from Abbott Immunology, Amgen and Lilly awarded to his institution. He serves in unpaid roles on two Pfizer sponsored trials and receives research support from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc (CORRONA).

Competing Interest

Kim has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America and Pfizer and tuition support for the Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard School of Public Health funded by Pfizer and Asisa. Solomon has received salary support through research grants from Abbott Immunology, Amgen and Lilly awarded to his institution. He serves in unpaid roles on two Pfizer sponsored trials and receives research support from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc (CORRONA).

References

- 1.Koenig W, Sund M, Fröhlich M, et al. C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999;99:237–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridker P, Cushman M, Stampfer M, et al. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, et al. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98:476–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelmann MD, Svendsen JH. Inflammation in the genesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2083–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu T, Li G, Li L, et al. Association between C-reactive protein and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful electrical cardioversion: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49 :1642–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Y, Lip G, Apostolakis S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60 :2263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conen D, Ridker P, Everett B, et al. A multimarker approach to assess the influence of inflammation on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in women. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1730–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnabel R, Larson M, Yamamoto J, et al. Relation of multiple inflammatory biomarkers to incident atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon DH, Kremer J, Curtis JR, et al. Explaining the cardiovascular risk associated with rheumatoid arthritis: traditional risk factors versus markers of rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1920–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;107:1303–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000054612.26458.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Rincón I, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. Association between carotid atherosclerosis and markers of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1833–40. doi: 10.1002/art.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Halm VP, Peters MJ, Voskuyl AE, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study, the CARRE Investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1395–400. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrao S, Messina S, Pistone G, et al. Heart involvement in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.057. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, et al. Risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke in rheumatoid arthritis: Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SY, Servi A, Polinski JM, et al. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in health care utilization data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R32. doi: 10.1186/ar3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glazer NL, Dublin S, Smith NL, et al. Newly detected atrial fibrillation and compliance with antithrombotic guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:246–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, et al. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:749–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peña JM, MacFadyen J, Glynn RJ, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, statin therapy, and risks of atrial fibrillation: an exploratory analysis of the JUPITER trial. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:531–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tveit A, Grundtvig M, Gundersen T, et al. Analysis of pravastatin to prevent recurrence of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:780–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyrnes A, Njølstad I, Mathiesen E, et al. Inflammatory Biomarkers as Risk Factors for Future Atrial Fibrillation. An Eleven-Year Follow-Up of 6315 Men and Women: The Tromsø Study. Gend Med. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.09.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christiansen C, Christensen S, Mehnert F, et al. Glucocorticoid use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a population-based, case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1677–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt M, Christiansen C, Mehnert F, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2011:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT) 2012 Nov 14; [cited 2012 December 31]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01594333.

- 27.Ridker P. Moving Beyond JUPITER: Will Inhibiting Inflammation Reduce Vascular Event Rates? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:295. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.