Abstract

Rh(I) carbenes were conveniently generated from readily available ynamides. These metal carbene intermediates could undergo metathesis with electron-rich or neutral alkynes to afford 2-oxo-pyrrolidines or be trapped by tethered alkenes to yield 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes, a common skeleton in numerous bioactive pharmaceuticals. Although the scope of the former is limited, the latter reaction tolerates various substituted alkenes.

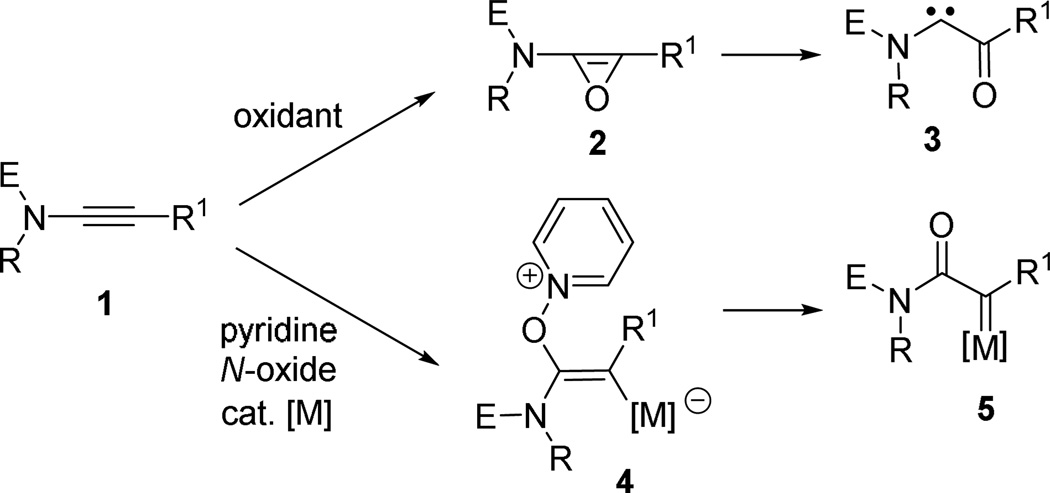

Metal carbene is one of the most important intermediates in organic synthesis and it is involved in numerous reactions such as cyclopropanation, C-H insertion, dipolar cycloaddition, and metathesis reactions.1 The most frequently used method for the preparation of metal carbenes is the decomposition of diazo compounds or related derivatives. Considering the hazardous and potential explosive nature of diazo compounds, other alternative carbene precursors are highly desirable. Recently, readily available ynamides2,3 have emerged as a versatile carbene precursor, and in particular, oxidation of ynamide 1 by dimethyl dioxirane (DMDO)4 or other oxidants5 was shown to afford the push-pull α-oxo carbene 3 through the oxirene intermediate 2 (Scheme 1). Interestingly, a complementary α-oxo gold carbene 5 (M = Au) was formed via intermediate 4, in the presence of gold catalysts and mild external oxidants (e.g. pyridine N-oxide).6,7

Scheme 1.

Complementary Carbenes from Ynamides

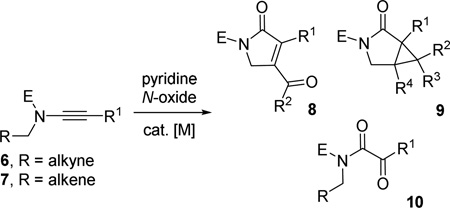

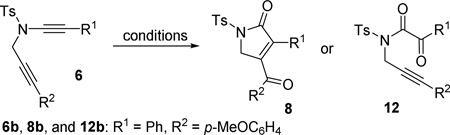

We envision that the choice of metal catalysts and ligands may have significant impact on the reactivity of carbene 5. We herein report that α-oxo Rh(I)-carbene 5 (M = Rh) can be generated from ynamides 6 or 7 and these Rh(I) carbenes then react with the tethered alkyne or alkene to afford heterocycles 8 or 9, respectively (eq 1). In contrast, keto-imide 10 was often the predominant product observed by us and others in the presence of gold(I) catalysts.6

|

(1) |

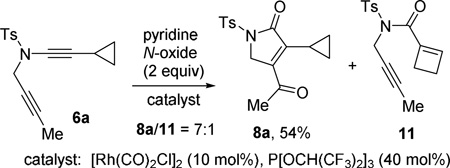

Our interest in the chemistry of cyclopropyl metal carbenes8 and π-acidic Rh(I) complexes9 prompted us to investigate the possibility of generating Rh(I) carbenes10 from ynamide 6a for cycloisomerization reactions. We prepared ynamide 6a and treated it with pyridine N-oxide and a complex of [Rh(CO)2Cl]2/P[OCH(CF3)2]3 (eq 2), which was shown to successfully promote acyloxy migration of propargylic esters,11 a process that was typically catalyzed by π-acidic transition metals.9,12 Compound 8a was isolated as the major product and cyclobutene 11 was also observed as the minor product. A metal carbene similar to intermediate 5 was presumably generated from ynamide 6a through the mechanism shown in Scheme 1. Ring expansion of this metal carbene intermediate would produce cyclobutene 11.8

|

(2) |

When the cyclopropyl group was replaced by other substituents, the formation of cyclobutene can be avoided and a 62% yield of cycloisomerization product 8b was obtained from diyne 6b under conditions employed for diyne 6a (entry 1, Table 1). The structure of product 8b was unambiguously assigned by X-ray analysis.13 The oxidative cycloisomerization of diyne 6b was then optimized under different conditions. Keto-imide 12b appeared when the phosphite ligand was removed (entry 2).14 Other ligands produced worse results (entries 3 and 4). No reaction occurred using Rh2(OAc)4 as the catalyst (entry 5). Interestingly, only keto-imide 12b was observed when gold catalyst was employed (entry 6). PtCl2 catalyst provided a complex mixture (entry 7). We then examined different substituted pyridine N-oxides, such as p-methoxy-, p-nitro-, 2,6-dichloro-, and 3,5-dichloropyridine N-oxides. Among them, 3,5-dichloropyridine N-oxide provided the best result (entry 8). Among all solvents that we screened, dioxane afforded the highest yield (entry 9). No desired product was obtained when other rhodium complexes, such as [Rh(COD)Cl]2, Wilkinson’s catalyst, and [Rh(COD)BF4] were employed.

Table 1.

Screening of Conditions for the Oxidative Cycloisomerization of Diyne 6a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Conditions | 8b / 12bb | Yieldc |

| 1 | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%), P[OCH(CF3)2]3 (20 mol%) | 1 : 0 | 62% |

| 2 | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%) | 5 : 1 | - |

| 3 | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%), P(OPh)3 (20 mol%) | no reaction | |

| 4 | [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%), [3,5-(CF3)2C6H3]3P (20 mol%) | 5 : 1 | - |

| 5 | Rh2(OAc)4 (5 mol%) | no reaction | |

| 6 | Au(PPh3)Cl (10 mol%), AgOTf (10 mol%) | 0 : 1 | - |

| 7 | PtCl2 (5 mol%) | complex mixture | |

| 8d | See entry 1 for catalyst | 1 : 0 | 70% |

| 9d,e | See entry 1 for catalyst | 1 : 0 | 78% |

Conditions: pyridine N-oxide (3 equiv), ClCH2CH2Cl, 80 °C, 4h, unless noted otherwise.

The ratio was determined by 1H NMR of crude product.

Isolated yield of 8b.

3,5-dichloropyridine N-oxide (3 equiv) was used as the oxidant.

Dioxane was used as the solvent.

With the optimized condition in hand, the scope of oxidative cycloisomerization of diyne 6 was investigated (Table 2). The yield of product 8c became slightly lower than that of 8b when R2 was a phenyl group. Both R1 and R2 could tolerate aryl groups with an ortho substituent (substrates 6d and 6e). When R2 was an electron-deficient aryl group (e.g. p-ClC6H4, p-NO2C6H4), a complex mixture was obtained. When R2 was a methyl group in substrate 6f, diene 13 was isolated in 10% yield. When R1 was hydrogen in substrate 6g, the carbene became more reactive and the reaction could be carried out at even room temperature. When R1 was an alkyl group in substrate 6h, 1,2-hydrogen migration product 14 was observed. For substrates 6i and 6j with a more functionalized R1 or R2 substituent, complex mixtures were observed.

Table 2.

Oxidative Cycloisomerization of Diynesa

| Substrate 6 | Product | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|

| 6c, R1 = Ph, R2 = Ph | 8c, | 67% |

| 6d, R1 = Ph, R2 = o-MeOC6H4 | 8d, | 76% |

| 6e, R1 = o-FC6H4, R2 = p-MeOC6H4 | 8e, | 75% |

| 6f, R1 = Ph, R2 = Me | 8f + 13 | 56% (10%)c |

| 6g,d R1 = H, R2 = p-MeOC6H4 | 8g, | 80% |

| 6h, R1 = PhCH2CH2CH2, R2 = p-MeOC6H4 | 8h + 14 | 67% (11%)e |

| 6i, R1 = H, R2 = CH2OCH2CH=CH2 | complex mixture | |

| 6j, R1 = CH=CHCH2OCH2CH=CH2, R2 = p-MeOC6H4 | complex mixture | |

| ||

Conditions: [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%), P[OCH(CF3)2]3 (20 mol%), 3,5-dichloropyridine N-oxide (3 equiv), dioxane, 80 °C, 4h.

Isolated yields.

Yield of byproduct 13.

rt, 3h.

Yield of byproduct 14.

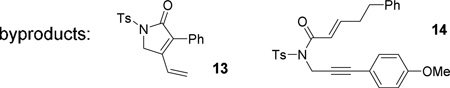

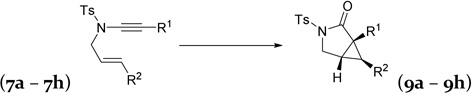

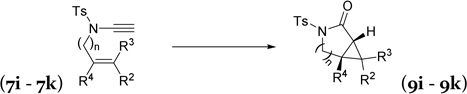

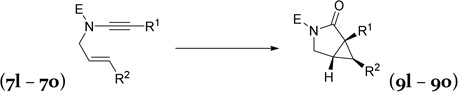

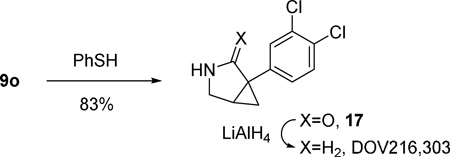

We then examined the reactivity of α-oxo Rh(I) carbenes towards alkenes (Table 3). Under previously optimized conditions for oxidative cycloisomerization of diynes, cyclopropanation product 9a was obtained in a 78% yield from enyne 7a. No improvement was observed after screening different Rh(I) complexes, ligands, or other substituted pyridine N-oxides. When Au(PPh3)Cl /AgOTf was employed as the catalyst, keto-imide 15a was isolated as the major product together with small amount of cyclopropane 9a. No reaction occurred when Rh2(OAc)4 was used as the catalyst.

Table 3.

Oxidative Cycloisomerization of Enynesa

| Substrate 7 | Product | Yieldb |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| 7a,c R1 = Ph, R2 = H | 9a, | 78% |

| 7b, R1 = H, R2 = H | 9b, | 88% |

| 7c, R1 = H, R2 = Ph | 9c, | 70% |

| 7d, R1 = H, R2 = p-MeOC6H4 | 9d, | 62% |

| 7e, R1 = H, R2 = p-NO2C6H4 | 9e, | 63% |

| 7f,c R1 = CH=CHCH2OBn, R2 = H | 9f, | 78% |

| 7g,c R1 = (CH2)3Ph, R2 = H | 16, | 68% |

| 7h, R1 = H, R2 = CH2OCH2CH=CH2 | complex mixture | |

| ||

| 7i, R2 = R3 = CH3, R4 = H, n=1 | 9i, | 87% |

| 7j, R2 = R3 = H, R4 = CH3, n=1 | 9j, | 72% |

| 7k, R2 = R3 = R4 = H, n=2 | 9k, | 78% |

| ||

| 7l, E = p-Ns, R1 = H, R2 = H | 9l, | 80% |

| 7m c E = p-Ns, R1 = Ph, R2 = H | 9m, | 76% |

| 7n,c E = p-Ns, R1 = p-CH3C6H4, R2 = H | 9n, | 60% |

| 7o,c E = o-Ns, R1 = 3,4-Cl2C6H3, R2 = H | 9o, | 81% |

| ||

Conditions: [Rh(CO)2Cl]2 (5 mol%), P[OCH(CF3)2]3 (20 mol%), 3,5-dichloropyridine N-oxide (1.0 equiv), dioxane, rt., 2h.

Isolated yields.

80 °C, 4–8 h.

The scope of oxidative cycloisomerization of enyne 7 was then investigated. For terminal ynamides 7b–7e, the reaction could be conducted at room temperature. Among them, terminal alkene 7b produced the best yield. A 70% yield was obtained for cyclopropanation of non-substituted styrene 7c. For diyne 6, R2 needs to be an electron-neutral or -rich aryl group to allow the oxidative cycloisomerization to proceed. On the other hand, it has been shown that α-oxo Rh(I) carbene derived from 1,2-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters only reacts with electron-deficient alkynes or alkenes.15 To our delight, both electron-rich and electron-poor styrenes underwent cyclopropanation to form bicyclic products 9d and 9e, respectively. It is worth to point out that a nitro group, which has been used as external oxidant in gold catalysis,7r can be tolerated.

Alkene and ether functionalities can be tolerated for the R1 substituent in substrate 7f. When R1 in substrate 7g was an alkyl group, surprisingly, hydrolysis product 16 was obtained. A complex mixture was observed when an olefin functional group was introduced to substrate 7h. Alkenes with a gem-dimethyl substituent or a methyl group on the internal position participated in the cyclopropanation and yielded products 9i and 9j, respectively. A six-atom tether could also be tolerated and bicyclic product 9k was prepared in a 78% yield.

|

(3) |

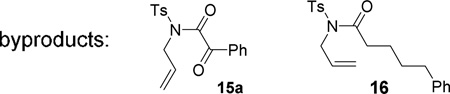

Nosyl group is generally easier to be removed than tosyl group.16 We were pleased to find that yields for products 9l and 9m were comparable to their tosyl counterparts 9a and 9b. The nosyl group in products 9o was removed smoothly under mild conditions to yield compound 17 (eq 3),16 which is the precursor for triple reuptake inhibitor DOV216,303.17,18 The 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane skeleton19 is also present in numerous other pharmaceuticals with broad biological activities, such as analgesic, antibacterial, and inhibition of aromatase.17,20

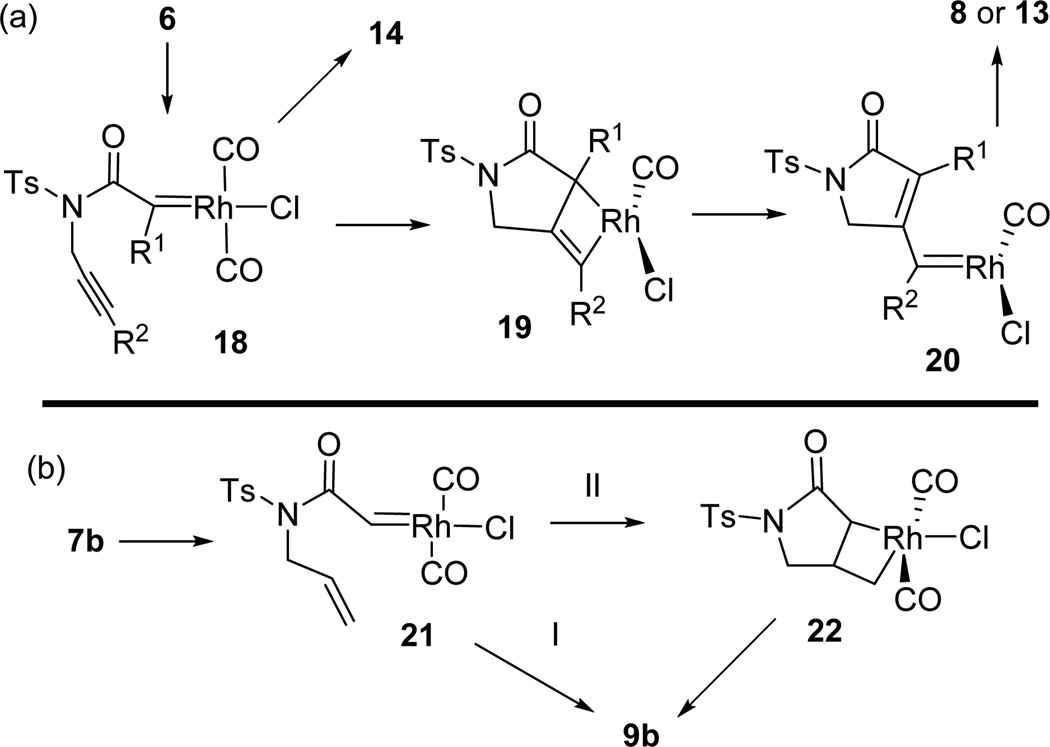

The mechanism for the oxidative cycloisomerization of diynes and enynes is proposed in Scheme 2. Metal carbenes 18 and 21 can be generated from ynamides 6 or 7b, respectively, following the mechanism shown in Scheme 1. Metathesis of metal carbene 18 with the tethered alkyne through metallacyclobutene 19 may afford a new carbene 20,21 which can be oxidized by pyridine N-oxide to yield product 8. When R1 or R2 was an alkyl group, 1,2-hydrogen migration produced small amount of byproducts 14 or 13, respectively. DFT calculations indicate that the barrier for the conversion of 18 to 20 is 20.7 kcal/mol and this process can take place at room temperature.13 Rh(I) carbene 21 may react with the tethered alkene to form product 9b in two pathways: I) a concerted cyclopropanation; II) a metathesis followed by reductive elimination through intermediate 22. DFT calculations suggest that pathway I is preferred since the reductive elimination of intermediate 22 in pathway II is relatively difficult.13

Scheme 2.

Proposed Mechanism for Oxidative Cycloisomerization of Diynes (a) and Enynes (b)

In summary, we have developed an efficient method for the generation of α-oxo Rh(I) carbenes from ynamides.10 We demonstrated that [Rh(CO)2Cl]2/P[OCH(CF3)2]3 complex was acidic enough to mediate the addition of external oxidant to ynamides under mild conditions. The Rh(I) carbenes produced from this process can then react with electron-rich or neutral alkynes or various substituted alkenes to afford heterocycles 2-oxo-pyrrolidines and 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]-hexanes, respectively. Further studies on the novel reactivity of Rh(I) carbenes are underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH (W.T., R01GM088285), the University of Wisconsin, and Natural Science Foundation of China (X.X., 21103094) for financial support of this research and Professor Hsung (UW-Madison) for reading and commenting on our manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Detailed experimental procedures, characterization and spectra data (IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.For selected reviews, see: Doyle MP. Chem. Rev. 1986;86:919. Padwa A, Hornbuckle SF. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:263. Ye T, Mckervey MA. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:1091. Padwa A, Weingarten MD. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:223. doi: 10.1021/cr950022h. Doyle MP, Forbes DC. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:911. doi: 10.1021/cr940066a. Doyle MP, Mckervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2861. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217. Davies HML, Hedley SJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1109. doi: 10.1039/b607983k. Davies HML, Manning JR. Nature. 2008;451:417. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. De Fremont P, Marion N, Nolan SP. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009;253:862. Davies HML, Denton JR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3061. doi: 10.1039/b901170f. Vougioukalakis GC, Grubbs RH. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1746. doi: 10.1021/cr9002424.

- 2.For recent reviews on the chemistry of ynamide, see: Dekorver KA, Li H, Lohse AG, Hayashi R, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Hsung RP. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:5064. doi: 10.1021/cr100003s. Evano G, Coste A, Jouvin K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:2840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905817.

- 3.For selected preparation methods of ynamide, see: Zhang YS, Hsung RP, Tracey MR, Kurtz KCM, Vera EL. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1151. doi: 10.1021/ol049827e. Hamada T, Ye X, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:833. doi: 10.1021/ja077406x. Coste A, Karthikeyan G, Couty F, Evano G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4381. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901099.

- 4.For the epoxidation of ynamides by DMDO, see: Al-Rashid ZF, Hsung RP. Org. Lett. 2008;10:661. doi: 10.1021/ol703083k. Al-Rashid ZF, Johnson WL, Hsung RP, Wei Y, Yao P-Y, Liu R, Zhao K. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8780. doi: 10.1021/jo8015067. Li H, Antoline JE, Yang J-H, Al-Rashid ZF, Hsung RP. New J. Chem. 2010;34:1309. doi: 10.1039/c0nj00063a.

- 5.For the epoxidation of ynamides by dioxiranes or a vanadium-based catalyst directed by propargylic alcohols, see: Couty S, Meyer C, Cossy J. Synlett. 2007:2819.

- 6.For the formation of α-oxo gold carbenes by the addition of external oxidants to ynamides, see: Li C-W, Pati K, Lin G-Y, Abu Sohel SM, Hung H-H, Liu R-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:9891. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004647. Vasu D, Hung H-H, Bhunia S, Gawade SA, Das A, Liu R-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6911. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102581. Li C, Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1738. doi: 10.1021/ol2002607. Davies PW, Cremonesi A, Martin N. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:379. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02736g. Mukherjee A, Dateer RB, Chaudhuri R, Bhunia S, Karad SN, Liu R-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15372. doi: 10.1021/ja208150d. Dateer RB, Pati K, Liu R-S. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:7200. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33030j.

- 7.For the formation of α-oxo gold carbenes by the addition of pyridine N-oxide to other alkyne derivatives, see: Ye L, Cui L, Zhang G, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3258. doi: 10.1021/ja100041e. Ye L, He W, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8550. doi: 10.1021/ja1033952. Lu B, Li C, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14070. doi: 10.1021/ja1072614. He W, Li C, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8482. doi: 10.1021/ja2029188. Ye L, He W, Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3236. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007624. Qian D, Zhang J. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:11152. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14788a. Qian D, Zhang J. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:7082. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31972a. He W, Xie L, Xu Y, Xiang J, Zhang L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:3168. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25235j. Wang Y, Ji K, Lan S, Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1915. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107561. Bhunia S, Ghorpade S, Huple DB, Liu R-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:2939. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108027. For pioneering work on the formation α-oxo gold carbenes by the addition of internal oxidant to alkyne derivatives, see: Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4160. doi: 10.1021/ja070789e. Li G, Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5156. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701449. Yeom HS, Lee JE, Shin S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7040. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802802. Cui L, Peng Y, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8394. doi: 10.1021/ja903531g. Davies PW, Albrecht SJC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:8372. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904309. Cui L, Zhang G, Peng Y, Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1225. doi: 10.1021/ol900027h. Yeom H-S, Lee Y, Lee J-E, Shin S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4744. doi: 10.1039/b910757f. For a review on the formation of α-oxo gold carbenes by oxygen transfer to alkynes, see: Xiao J, Li X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7226. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100148.

- 8.(a) Xu H, Zhang W, Shu D, Werness JB, Tang W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8933. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu R, Zhang M, Wyche TP, Winston-Mcpherson GN, Bugni TS, Tang W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7503. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu R, Zhang M, Winston-Mcpherson G, Tang W. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:4376. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34609e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shu X-Z, Shu D, Schienebeck CM, Tang W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:7698. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35235d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For selected examples of generating Rh(I) carbenes from Fisher carbenes for cycloisomerizations, see: Barluenga J, Vicente R, Lopez LA, Rubio E, Tomas M, Alvarez-Rua C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:470. doi: 10.1021/ja038817q. Barluenga J, Vicente R, Barrio P, Lopez LA, Tomas M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5974. doi: 10.1021/ja049200r. Barluenga J, Vicente R, Barrio P, Lopez LA, Tomas M, Borge J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14354. doi: 10.1021/ja045459y. Barluenga J, Vicente R, Lopez LA, Tomas M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7050. doi: 10.1021/ja0586788. Gomez-Gallego M, Mancheno MJ, Sierra MA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:44. doi: 10.1021/ar040005r.

- 11.(a) Shu X-Z, Huang S, Shu D, Guzei IA, Tang W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:8153. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shu X-Z, Li X, Shu D, Huang S, Schienebeck CM, Zhou X, Robichaux PJ, Tang W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5211. doi: 10.1021/ja2109097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang S, Li X, Lin CL, Guzei IA, Tang W. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:2204. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17406e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For selected reviews on π-acidic metal catalysis, see: Marion N, Nolan SP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2750. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604773. Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3410. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. Hashmi ASK. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3180. doi: 10.1021/cr000436x. Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. Wang S, Zhang G, Zhang L. Synlett. 2010:692. Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5232. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907078.

- 13.See Supporting Information for details.

- 14.The keto-imide product was also observed by Hsung et al. when Wilkinson's catalyst and AgBF4 was attempted at one time as described in reference (4b).

- 15.Shibata Y, Noguchi K, Tanaka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7896. doi: 10.1021/ja102418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuyama T, Jow CK, Cheung M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6373. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Epstein JW, Brabander HJ, Fanshawe WJ, Hofmann CM, Mckenzie TC, Safir SR, Osterberg AC, Cosulich DB, Lovell FM. J. Med. Chem. 1981;24:481. doi: 10.1021/jm00137a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang M, Jovic F, Vickers T, Dyck B, Tamiya J, Grey J, Tran JA, Fleck BA, Pick R, Foster AC, Chen C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:3682. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu F, Murry JA, Simmons B, Corley E, Fitch K, Karady S, Tschaen D. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3885. doi: 10.1021/ol061650w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For a review on the synthesis of 3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes, see: Krow GR, Cannon KC. Org. Prep. Proc. Int. 2000;32:103.

- 20.(a) Stanek J, Alder A, Bellus D, Bhatnagar AS, Hausler A, Schieweck K. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:1329. doi: 10.1021/jm00108a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Renslo AR, Gao HW, Jaishankar P, Venkatachalam R, Gomez M, Blais J, Huband M, Prasad J, Gordeev MF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For related metathesis involving Rh(II) carbenes derived from diazo compounds, see: Padwa A, Krumpe KE, Zhi L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:2633. Hoye TR, Dinsmore CJ, Johnson DS, Korkowski PF. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4518. Hoye TR, Dinsmore CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4343.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.