Abstract

One of the defining features of the nervous system is its ability to modify synaptic strength in an experience-dependent manner. Chronic elevation or reduction of network activity activates compensatory mechanisms that modulate synaptic strength in the opposite direction (i.e. reduced network activity leads to increased synaptic strength), a process called homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Among the many mechanisms that mediate homeostatic synaptic plasticity, retinoic acid (RA) has emerged as a novel signaling molecule that is critically involved in homeostatic synaptic plasticity induced by blockade of synaptic activity. In neurons, silencing of synaptic transmission triggers RA synthesis. RA then acts at synapses by a non-genomic mechanism that is independent of its well-known function as a transcriptional regulator, but operates through direct activation of protein translation in neuronal dendrites. Protein synthesis is activated by RA-binding to its receptor RARα, which functions locally in dendrites in a non-canonical manner as an RNA-binding protein that mediate RA’s effect on translation. The present review will discuss recent progress in our understanding of the novel role of RA, which led to the identification of RA as a critical synaptic signaling molecule that mediates activity-dependent regulation of protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites.

This article is part of a Special Issue entitled ‘Homeostatic Plasticity’.

Keywords: retinoic acid, homeostatic synaptic plasticity, synaptic scaling, local protein synthesis, retinoic acid receptor α, Fragile-X syndrome

1. Introduction

A dynamic range of network activity is essential for optimal information coding in the nervous system. Normal brain function requires neurons to operate at a constant overall activity level, and to maintain a balance between the relative strength of individual synapses. It is thought that in a neuron, activity levels are kept constant by a process called homeostatic synaptic plasticity (HSP). HSP uniformly adjusts the strengths of a large portion if not all synapses in a neuron to maintain a particular activity level. HSP may be mediated by alterations in pre-synaptic transmitter release, synaptic vesicle loading, postsynaptic receptor function, or neuronal membrane properties (Davis, 2006; Rich and Wenner, 2007; Turrigiano, 2012). Several signaling pathways are involved in various forms of HSP in the mammalian CNS and at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (Turrigiano, 2008; Yu and Goda, 2009). For example, in mammalian neurons, adjustments in the relative expression levels of CaMKIIα vs. IIβ (Thiagarajan et al., 2002) and CaMKIV-regulated transcriptional events (Ibata et al., 2008) mediate homeostatic compensation for changes in neuronal firing and synaptic activity. Additionally, the level of Arc/Arg3.1, an immediate-early gene that is rapidly induced by neuronal activity (Guzowski et al., 2005), modulates homeostatic plasticity through a direct interaction with the endocytic pathway (Shepherd et al., 2006). Recent findings also implicated inactivity-induced postsynaptic synthesis and release of BDNF, which acts retrogradely to enhance presynaptic functions in HSP (Jakawich et al., 2010). At the Drosophila neuromuscular junction, homeostatic synaptic plasticity is manifested mainly by changes in presynaptic release modulated by retrograde signaling mechanisms (Davis and Bezprozvanny, 2001), and multiple pathways have been implicated involving molecules such as dysbindin (Dickman and Davis, 2009), Cav2.1 (Frank et al., 2006), the BMP ligand Gbb (Goold and Davis, 2007), Eph receptor and ephexin (Frank et al., 2009), and snapin (Dickman et al., 2012). In addition to these neuronal and muscle-derived molecules, glia-derived factors, such as cytokine TNFα, have been demonstrated to control synaptic strength and to influence HSP (Beattie et al., 2002; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). Although a bewildering number of different pathways may contribute to HSP, recent progress has identified fundamental events that underlie many forms of HSP in the mammalian nervous system, thereby suggesting that a limited number of basic molecular mechanisms could account for this important process.

Synaptic scaling is a form of HSP that was initially discovered in cultured cortical neurons where neuronal activity was either chronically blocked with tetradotoxin (TTX), or elevated by inhibition of GABAergic synaptic transmission (Turrigiano et al., 1998). The expression of synaptic scaling is thought to involve transcriptional events that alter the abundance of AMPA-type glutamate receptors in the postsynaptic membrane (Turrigiano, 2012). An important property of synaptic scaling is that all synapses of a neuron are modified concurrently in a multiplicative fashion (i.e., stronger synapses are changed proportionally more than weaker synapses), thereby preserving the relative synaptic weights of the overall circuit (Thiagarajan et al., 2005; Turrigiano et al., 1998) but see (Echegoyen et al., 2007). However, several recent studies show that a fast adaptive form of HSP can be induced when excitatory synaptic transmission is blocked in conjunction with TTX treatment (Ju et al., 2004; Sutton et al., 2006; Sutton et al., 2004). Importantly, this rapid form of HSP is independent of transcription, and is mediated by the local synthesis and synaptic insertion of homomeric GluA1 receptors, allowing adjustment of synaptic strength at spatially discrete locations in a neuron (Table 1). Although several biochemical signaling pathways can trigger dendritic protein synthesis upon increase in neuronal activity (Kelleher et al., 2004; Klann and Dever, 2004; Schuman et al., 2006), the signaling pathways involved in this type of inactivity-induced synaptic scaling remain largely unclear.

Table 1.

Comparison of mechanistic distinction between RA-dependent and RA-independent homeostatic synaptic plasticity

| RA-dependent homeostatic synaptic plasticity | RA-independent homeostatic synaptic plasticity |

|---|---|

| Requires blockade of synaptic activity and reduction of dendritic calcium levels (i.e. TTX+APV, CNQX, nifedipine) | Requires action potential blockade only (i.e. TTX), sensitive to somatic calcium levels |

| Requires local protein translation | Requires transcription events |

| Involve all synapses or a subset of synapses of a neuron (can be both global and local) | Involves all synapses of a neuron (global) |

| Requires normal FMRP function | Operates normally in FMRP knockout neuron |

| Inserts GluA2-lacking calcium-permeable AMPA receptors | Inserts GluA2-containing calcium-impermeable AMPA receptors |

| Rapid onset and expression | Slower in expression, lags behind the RA-dependent phase of HSP |

Several years ago we identified retinoic acid (RA) as a key mediator of transcription-independent HSP (Aoto et al., 2008). Here, we will review recent progress in our understanding of the non-canonical role of RA that emerged from this observation, leading to the identification of RA as a novel synaptic signaling molecule that mediates activity-dependent regulation of protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. We will discuss the function of RA not only in the context of HSP, but also in other forms of synaptic plasticity, and relate the RA-dependent synaptic signaling pathway to neurological diseases. Since this type of RA signaling has only been examined in vertebrates, we will limit our discussion to the vertebrate nervous system.

2. Retinoid signaling in the adult nervous system

Biological sources of retinoids include preformed Vitamin A from animal-derived food, or pro-Vitamin A carotenoids (e.g. β-carotene) from plant-derived foods. The majority of preformed Vitamin A and pro- Vitamin A are converted into all-trans-retinol by a series of reactions in the intestinal lumen and mucosa. Upon absorption into enterocytes, re-esterified retinol is transported to the liver, which is the major site for retinoid storage in the body. Retinol is secreted from the liver in response to the body’s needs and is transported in the blood bound to retinol binding protein (RBP). In target cells, a membrane receptor for RBP mediates cellular uptake of retinol (Kawaguchi et al., 2007). Retinol is locally metabolized into its bioactive derivative all-trans-retinoic acid (RA), which exerts its effects in a variety of biological systems.

RA is synthesized from retinol in two oxidation reactions. First, cytosolic retinol dehydrogenase (ROLDH) or alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) convert retinol to retinal (retinaldehyde). Second, retinal dehydrogenase (RALDH) oxidizes retinal to RA. These enzymes are expressed in the adult mammalian brain (Krezel et al., 1999; Zetterstrom et al., 1999). Local RA synthesis in adult brain has been demonstrated using transgenic mice expressing LacZ downstream of three canonical retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) (Thompson Haskell et al., 2002). Strikingly, in the forebrain, cerebellum and meninges, the rates of RA synthesis are comparable to, or exceed, the rates of RA synthesis in liver (Dev et al., 1993). Taken together, these studies unequivocally establish that RA synthesis occurs in the adult brain (Dev et al., 1993; Wagner et al., 2002). While most studies on RA actions are traditionally focused on its role as a transcriptional activator, various observations mostly in culture systems have demonstrated rapid transcription-independent, non-genomic RA effects that occur at the cellular periphery or at the plasma membrane (Ko et al., 2007; Masia et al., 2007; Uruno et al., 2005). Below we will discuss our recent observations on non-genomic RA actions in brain function: surprisingly, RA exerts a critical control over synaptic strength in HSP, an effect that is rapid and independent of transcription.

During development of the nervous system, spatial RA gradients emanating from localized foci of RA synthesis contribute to brain patterning, morphogenetic effects that are due to the opposing actions of the two main classes of RA metabolic enzymes, the RA-synthesizing RALDHs and the RA-degrading CYP26 enzymes of a cytochrome P450 family (Berggren et al., 1999; Fujii et al., 1997; McCaffery and Drager, 1993; Niederreither et al., 1997; Pennimpede et al., 2010; Ross and Zolfaghari, 2011). Similarly, in mature CNS, RA is not uniformly available but is only present in discrete regions of the brain (Bremner and McCaffery, 2008; Lane and Bailey, 2005). In cultured hippocampal neurons, RA is not detectable when neurons are active (Aoto et al., 2008). RA synthesis is strongly induced by loss of synaptic activity and a decrease in dendritic calcium levels (Wang et al., 2011), supporting its role as an important signaling molecule that modulates neuronal function in an active manner.

The action of RA is primarily mediated by nuclear retinoid receptor proteins called retinoic acid receptors (RAR-α, -β, -γ) and retinoid ‘X’ receptors (RXR-α, -β, -γ). Like other members of the steroid receptor family, RARs and RXRs are transcription factors. Although structurally similar, the ligand specificity differs between them in that RARs bind all-trans-RA and 9-cis-RA with high affinity, whereas RXRs bind exclusively 9-cis-RA (Soprano et al., 2004). Because 9-cis-RA is undetectable in vivo, the effects of retinoids on gene transcription are presumed to be mediated by RA binding to RARs. In the adult mammalian brain, RARα is abundant in the cortex and hippocampus, RARβ is highly expressed in the basal ganglia, and RARγ is not detectable (Krezel et al., 1999; Zetterstrom et al., 1999). Although RARs are concentrated in cell nuclei, they shuttle in and out of the nucleus like other nuclear receptors. For example, when an RARα-GFP fusion protein was expressed in HeLa cells, 20% of the total protein was cytosolic, but rapidly moved into the nucleus upon RA-binding (Maruvada et al., 2003). RARα has also been shown to be both cytoplasmic and nuclear in mature hippocampal neurons (Aoto et al., 2008). Moreover, a recent study (Huang et al., 2008) reported that the subcellular localization of RARα exhibited a developmental shift from the nucleus to the cytosol. The expression levels of total RARα in postnatal hippocampus gradually decrease over time with increasing developmental maturity of the neurons. After postnatal day 29, equal or greater amounts of RARα were detected in the cytosol compared to the nucleus in both pyramidal and granule cells, consistent with the intriguing possibility that RARα may assume a function in the cytoplasm of mature neurons that differs from its function as a transcription factor.

In the developing nervous system, RA signaling is involved in neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation, and operates exclusively by regulating gene transcription. However, the evidence reviewed above, especially the continuing high levels of RA synthesis, indicates that RA signaling may also play an important role in the mature brain (Lane and Bailey, 2005). RA signaling has been implicated in activity-dependent long-lasting changes of synaptic efficacy that are thought to be the cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory. For example, impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) have been demonstrated in mice lacking RARβ or both RARβ and RARγ (Chiang et al., 1998). The function of RARα in hippocampal plasticity remains unknown because targeted disruption of RARα results in early postnatal lethality (Lufkin et al., 1993). Additionally, both LTP and LTD are reduced in Vitamin A deficient mice, but the impaired plasticity can be reversed after administration of a Vitamin A supplemented diet, indicating that synaptic plasticity is modulated by retinoids in adult brain (Misner et al., 2001). The involvement of RA in adult brain function is further supported by deficits in learning and memory tasks observed in RAR null or Vitamin A-deficient mice (Chiang et al., 1998; Cocco et al., 2002).

3. Synaptic RA signaling

3.1. RA as a potent regulator of dendritic protein synthesis and synaptic strength

The discovery of the role of RA in HSP was fortuitous. We were intrigued by the potential involvement of RA signaling in Hebbian plasticity and hippocampal dependent learning, and investigated the direct effect of RA on excitatory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. We found that acute RA application rapidly increased the amplitude of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs). The observed enhancement of mEPSC amplitude by RA was multiplicative in nature, reminiscent of synaptic scaling (Aoto et al., 2008). Additional experiments showed that the synaptic effect of RA was independent of the formation of new dendritic spines (Chen and Napoli, 2008), but instead operated by stimulating the synthesis and insertion of new postsynaptic GluA1-containing glutamate receptors into existing synapses (Aoto et al., 2008). Different from the known function of RA as a transcription factor, the effects of RA on synaptic transmission and surface GluA1 expression could not be blocked by transcription inhibitors, but were abolished by protein synthesis inhibitors. Moreover, RA directly stimulated GluA1 protein synthesis in synaptoneurosomes, a biochemical preparation that lacks nuclear components and therefore operates in a transcription-independent manner (Aoto et al., 2008; Poon and Chen, 2008).

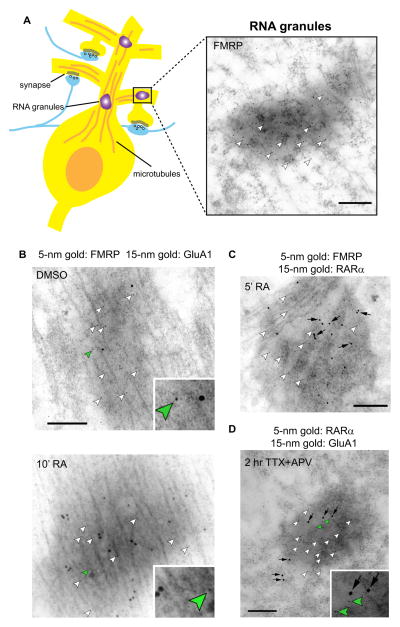

The nature of RA-gated protein translation in neurons was further characterized by immunogold electron microscopy (Maghsoodi et al., 2008). Local protein synthesis in dendrites requires mRNAs and the translation machinery, both of which are trafficked to dendrites through assembly of an electron-dense structure termed RNA granules, which are large RNA-protein complexes that serve not only as mRNA trafficking units but also as storage compartments for mRNAs and translation machinery (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006; Krichevsky and Kosik, 2001). Consistent with the rapid GluA1 synthesis induced by RA in synaptoneurosomes, brief RA treatments drastically increased the GluA1 labeling in dendritic RNA granules, a process that was blocked by inhibitors of protein synthesis, but not transcription (Maghsoodi et al., 2008) (Fig. 1A and 1B). Thus, a novel non-genomic function underlies RA‘s action at the synapse.

Fig. 1.

FMRP and RARα are present in neuronal RNA granules. (A) Left: A cartoon showing location of RNA granules in neurons. Right: FMRP, labeled by 5 nm gold particles (arrowheads), is enriched in dendritic RNA granules. (B) Double immunogold labeling of FMRP (arrowheads) and GluA1 in dendritic RNA granules of cultured hippocampal neurons. Ten-minute treatment of 1 μM RA, but not DMSO rapidly increased GluA1 protein synthesis in RNA granules. (C) RA stimulation increased RARα (arrows) accumulation in RNA granules within 5 min of treatment. (D) RARα (arrowheads) is found enriched in RNA granules actively translating GluA1 (arrows). All scale bars: 200 nm. Adapted from Maghsoodi et al., 2008.

The multiplicative increase in mEPSC amplitude and the activation of local protein synthesis by RA led us to explore its potential involvement in HSP. Indeed, we established that RA is both necessary and sufficient for HSP induced by blocking synaptic activity (i.e. TTX+APV treatment, note that TTX blocks voltage-gated sodium channels and APV blocks NMDA-type glutamate receptors), but not for HSP induced by chronic blockage of action potentials with TTX alone (Wang et al., 2011). Inhibition of RA synthesis prevented upregulation of synaptic strength induced by activity blockade. HSP induced by activity blockade occludes further increase in synaptic strength by RA, placing RA into the signaling pathway downstream of synaptic activity blockade.

3.2. RA as a synaptic activity sensor: a key component of the feedback loop linking alterations in synaptic activity to HSP

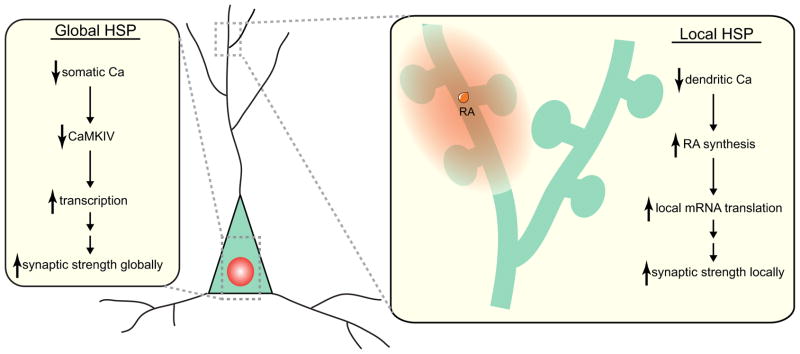

The requirement of RA synthesis in HSP and the ability of RA to increase synaptic strength imply that RA is a critical link between synaptic activity levels and synaptic strength. Indeed, we found using an RA reporter system that RA synthesis was dramatically stimulated by activity blockade with TTX and APV (Aoto et al., 2008). However, a major source of confusion in understanding HSP is that many different experimental manipulations seem to lead to HSP (Aoto et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2004; Soden and Chen, 2010; Sutton et al., 2006; Thiagarajan et al., 2005; Turrigiano, 2008). Thus, it was unclear whether RA mediates many forms of HSP, or whether RA is a peculiarity for a single form of HSP that is just an exotic exception. By analyzing different well-established HSP induction protocols, we found that stimulation of RA synthesis is required for all forms of HSP that are rapidly induced by blocking postsynaptic activity (e.g., treatments with TTX+APV, CNQX, or TTX+CNQX), whereas RA synthesis is not required for HSP induced by prolonged blockade of action potential firing alone (i.e., TTX-alone), which takes longer to develop (Wang et al., 2011). This led us to speculate that at least two signaling pathways mediate HSP and operate in parallel with different time courses: an RA- and local protein synthesis-dependent rapid pathway and an RA- and local protein synthesis-independent slow pathway that requires transcription of new mRNAs, as was illustrated initially by Schuman and colleagues (Sutton et al., 2006) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Global and local mechanisms for homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Global HSP is triggered by a reduction in neuronal firing that leads to a drop in somatic calcium level. This decreases the amount of activated CaMKIV in the nucleus, which leads to increased transcription of “scaling factors”, and enhanced accumulation of heteromeric AMPA receptors globally at all excitatory synapses. The increased excitatory synaptic strength thus restores neuronal firing rate back to normal. Local HSP is triggered by a drop in dendritic calcium levels due to reduced excitatory synaptic transmission in a subset of synapses. Reduced calcium levels in dendrites dis-inhibit RA synthesis. RA enhances local protein synthesis and synaptic insertion of homomeric AMPA receptors locally in dendrites (depicted by the orange circle), thus restores dendritic calcium levels back to normal.

We found that when synaptic activity and neuronal firing are both blocked (i.e. by treatment of neurons with TTX+APV), the immediate engagement of early RA-dependent cellular events is triggered by the resulting drop in dendritic calcium concentrations, which stimulates RA synthesis. RA thus leads to a rapid increase in excitatory synaptic strength produced by synaptic insertion of locally translated AMPA receptors that contain GluA1, lack GluA2, and are calcium-permeable (Aoto et al., 2008) (Fig. 2). The slow RA-independent pathway of HSP, conversely, is triggered by reduced neuronal firing, a drop in somatic calcium influx, reduced activation of CaMKIV, and an increase in transcription (Fig. 2); this pathway involves synaptic insertion of GluA2-containing AMPA receptors (Ibata et al., 2008). The fact that TTX-treatment alone can induce HSP, albeit with a delay, shows that the fast and slow pathways of HSP are mechanistically distinct and are independent of each other. Interestingly, the GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors that are inserted during the rapid pathway of HSP are transient, and are slowly replaced by GluA2-containing AMPA receptors (Sutton and Schuman, 2006), and our unpublished observation). This observation suggest that the calcium-permeable AMPA receptors lacking GluA2 inserted by the rapid HSP pathway inactivate this pathway in a negative feedback loop while the slow pathway of HSP is beginning to operate.

Two molecular mechanisms have been proposed by which a drop in calcium concentration could induce the rapid HSP pathway. First, we demonstrated that dendritic calcium serves as a critical inhibitor of RA synthesis in neurons, such that any decrease in dendritic calcium activates RA synthesis (Wang et al., 2011). For example, when cellular calcium is buffered by BAPTA or EGTA, RA synthesis is turned on rapidly. Additionally, blockade of L-type calcium channels is as efficient as synaptic activity blockers in inducing RA synthesis and HSP in a cell-autonomous manner, strongly suggesting a negative coupling between dendritic calcium levels and RA synthesis (Wang et al., 2011). The RA-induced synthesis and insertion of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors thus serves as a negative feedback signal to halt RA synthesis, thereby stabilizing synaptic strength. The downstream calcium-dependent signaling cascade that regulates RA synthesis remains to be determined in future work.

A second mechanism that may operate in parallel with the RA-dependent pathway to mediate the rapid HSP focuses on eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (eEF2). Sutton and colleagues (Sutton et al., 2007) showed elegantly that miniature synaptic transmission strongly promotes eEF2 phosphorylation, thereby inactivating it. Thus, blocking synaptic activity leads to rapid dephosphorylation and activation of eEF2 in a spatially controlled fashion, allowing local protein synthesis to occur. Because phosphorylation of eEF2 is catalyzed by a calcium/CaM-dependent protein kinase (Nairn et al., 1987), calcium entry through newly inserted calcium-permeable AMPA receptors serves as a negative feedback signal to slow down local protein synthesis, enabling the transition to the late phase HSP.

3.3. Dendritic RARα mediates synaptic RA signaling – the double life of a versatile molecule

How does RA increase synaptic strength? As mentioned above, the transcriptional effects of RA are primarily mediated by RARs. Among the three isoforms of RARs, RARα is most abundantly expressed in the hippocampus, while RARβ is mostly found in the basal ganglia, and RARγ is not detectable in adult brain (Krezel et al., 1999; Zetterstrom et al., 1999). Targeted constitutive gene deletions provided evidence for a limited role of RARβ and RARγ in the adult brain, but the function of RARα in the adult brain remained unexplored due to early postnatal lethality of constitutive RARα knockout mice (Lufkin et al., 1993). To avoid confounding factors in constitutive RARα knockout mice, such as abnormal neuronal development and perinatal lethality (LaMantia, 1999; Lufkin et al., 1993; Mark et al., 1999), we studied the involvement of RARα in synaptic RA signaling using shRNA-dependent knockdowns and conditional knockout mice (Sarti et al., 2012). Both acute knockdown and conditional knockout of RARα prevented RA-dependent HSP, and blocked the RA-mediated increase in synaptic strength (Aoto et al., 2008; Sarti et al., 2012). Moreover, we observed that RARα is transiently concentrated in actively translating dendritic RNA granules of neurons (Maghsoodi et al., 2008) (Fig. 1C and 1D), suggesting an unanticipated involvement of RARα in local protein synthesis. Indeed, RARα in mature neurons acts as an mRNA-binding protein whose dendritic localization is evident in postnatal neurons (Aoto et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2008) and is dictated by a nuclear export signal (NES) (Poon and Chen, 2008).

Similar to other nuclear receptors, RARα consists of an N-terminal activation domain, a DNA-binding domain (DBD), a hinge region, a ligand binding domain (LBD) and a C-terminal F domain whose function was largely unknown (Evans, 1988; Green and Chambon, 1988; Tasset et al., 1990; Tora et al., 1988a; Tora et al., 1988b). Upon RA binding, RARα undergoes a conformational change which results in the release of corepressors, the recruitment of coactivators, and the stimulation of gene transcription. RARα contains a classical NES in the LBD, and mutation of the RARα NES leads to an accumulation of RARα in the nucleus (Poon and Chen, 2008). The c-terminal F domain of RARα acts as an RNA binding domain that interacts with mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner, and RARα binding inhibits translation of these target mRNAs (Poon and Chen, 2008). This inhibition is released by RA binding to RARα, thus de-repressing translation and accounting for the activation of GluA1 synthesis by RA.

The function of RARα in mRNA binding and translational regulation was further validated in the context of HSP. Acutely deleting RARα in neurons from RARα conditional KO mice eliminates RA’s effect on excitatory synaptic transmission, and simultaneously inhibits activity blockade-induced HSP (Sarti et al., 2012). By expressing various RARα rescue constructs in RARα knockout neurons, it was concluded that the DNA-binding domain of RARα is dispensable for regulating synaptic strength, further supporting the notion that RA and RARα act in a non-transcriptional manner in this context (Sarti et al., 2012). By contrast, the ligand-binding domain (LBD) and the mRNA-binding domain (F-domain) of RARα are both necessary - and are together sufficient - for the function of RARα in HSP. Furthermore, the LBD/F domains are sufficient to support the rapid pathway of HSP that leads to insertion of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. Thus, unequivocal genetic approaches confirmed that RA and RARα perform essential non-transcriptional functions in regulating synaptic strength.

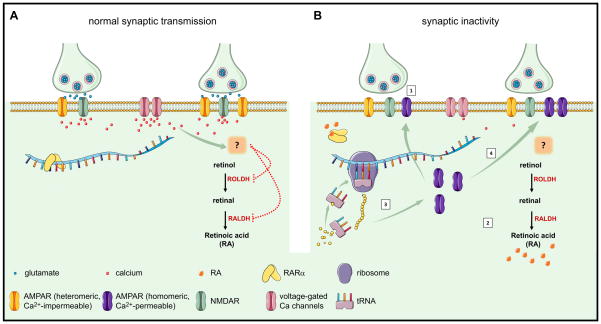

Based on these data, we propose a model that describes the synaptic action of RA in the context of HSP (Fig. 3). At basal activity levels when both action-potential driven and spontaneous miniature synaptic events are present, postsynaptic calcium levels are kept at a sufficiently high level to suppress RA synthesis. Unliganded RARα binds to target mRNAs and represses their translation (Fig. 3A). When the postsynaptic calcium concentration drops below a critical level due to synaptic activity blockade, the inhibition of RA synthesis is removed. Newly synthesized RA then binds to RARα, allowing it to release target mRNAs, thereby de-repressing local protein synthesis. Among the many mRNA substrates of RARα, GluA1 mRNA and its translation play a direct role in enhancing postsynaptic AMPA receptor abundance and HSP expression (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A model for RA-mediated regulation of synaptic strength. (A) Normal excitatory synaptic transmission maintains dendritic calcium levels above a critical threshold, which, through an unknown mechanism, inhibits RA synthesis. (B) During synaptic inactivity (➀), reduced dendritic calcium levels enable RA synthesis (➁). Binding of RA to RARα de-represses mRNA translation and allows dendritic protein synthesis to occur locally (➂). Newly synthesized calcium-permeable homomeric AMPA receptors are inserted into local synapses (➃), leads to increased excitatory synaptic strength.

4. RA and other types of synaptic plasticity

Although the synaptic action of RA has been tightly linked to HSP, this finding does not mean that the impact of RA on synapses is limited to HSP. In addition to evidence showing that vitamin A deficiency leads to impaired hippocampal Hebbian plasticity and learning, a recent study using a dominant negative form of RARα expressed in the adult forebrain demonstrated impairments in AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission, hippocampal LTP, hippocampal-dependent social recognition, and spatial memory (Nomoto et al., 2012). These findings suggest that the functional impact of RA may go beyond HSP.

The history of a neuron’s activity determines its current biochemical state and its ability to undergo synaptic plasticity, a phenomenon referred to as meta-plasticity (Abraham and Bear, 1996). A number of factors have been proposed to contribute to meta-plasticity through influencing the state of the neuron/synapse. For example, the postsynaptic NMDA receptor composition (GluN2A- versus GluN2B-containing (Yashiro and Philpot, 2008)), the phosphorylation state of AMPA receptors (Lee et al., 2000), the ratio of CaMKIIα to CaMKIIβ (Thiagarajan et al., 2007), presynaptic endocannabinoid receptors (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2004), as well as signaling by various neuromodulators (Huang et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010; Scheiderer et al., 2004; Seol et al., 2007) have all been shown to act as mechanisms for meta-plasticity. Aside from its ability to rapidly enhance excitatory synaptic transmission (Aoto et al., 2008), RA also alters inhibitory synaptic transmission (unpublished observation). Therefore, RA likely is a candidate ‘metaplasticity molecule’ that may change the state of a neuron (e.g., its excitatory/inhibitory balance) and thus influence Hebbian plasticity, through a mechanism potentially distinct from that mentioned above. Thus, although the primary functional significance of HSP has always been thought to maintain neural network stability by dynamically regulating neuronal excitability, the biochemical events involved in the homeostatic adjustment of synaptic activity may well directly influence the ability of the neuron to undergo Hebbian-type plasticity.

HSP was initially thought to operate at a global level (e.g. changes occur to all synapses of a neuron, Fig. 2A) (Turrigiano, 2008). A number of recent studies provided evidence for additional “local” processes that can act on individual synapses or a small subset of synapses (Branco et al., 2008; Hou et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2004; Sutton and Schuman, 2006; Yu and Goda, 2009). In this sense, ‘local HSP’ would define HSP as a process that does not maintain a constant activity level in an entire neuron, but in a neuronal subcompartment, such as a dendritic segment. Many properties of synaptic RA make it an attractive molecule for mediating both global (not input-specific) and local (input-specific) HSP. The RA synthesis enzyme RALDH is expressed throughout the soma and dendrites of neurons (Aoto et al., 2008). It has been shown that RA is synthesized within a neuron experiencing reduced synaptic activity, and that the RA synthesis machinery is sensitive to changes in synaptic/dendritic calcium influx but not somatic calcium influx (Wang et al., 2011). Together, these observations suggest that RA synthesis can occur in a subset of synapses or in discrete regions of dendrites experiencing decreased synaptic activity. A fascinating property of RA is that it is a small lipophilic molecule that can potentially freely diffuse inside a neuron and through cell membranes, although such diffusion may be restricted by the presence of cellular RA-binding proteins and by regional expression of one of the RA degradation CYP26 enzymes (Ray et al., 1997). This means that RA’s action may be both autocrine and paracrine, i.e. local in the vicinity of the synapses experiencing reduced synaptic activity and calcium influx, but at the same time its action may extend beyond those synapses. One intriguing observation is that decreased excitatory synaptic activity during blockade of AMPA receptors not only induces HSP at excitatory synapses, but also decreases the strength of inhibitory synapses (unpublished results). The changes at excitatory and inhibitory synapses both require RA synthesis. This is one example that RA’s action is likely not restricted to synapses next to which RA synthesis is triggered, but can act as a communicator between excitatory and inhibitory synapses (or other neighboring excitatory synapses) (Fig. 2B). Additionally, we and others observed changes in presynaptic function (manifested as an increase in mEPSC frequency) when synaptic scaling was induced in more mature neurons (Thiagarajan et al., 2005, Jakawich et al, 2010, Wang et al., 2011). These changes may be dependent on postsynaptic BDNF as a secreted signal (Jakawich et al., 2010), but also require RA synthesis (Wang et al., 2011). It is possible that RA stimulates de novo synthesis of trans-synaptic signaling molecules such as BDNF, which then communicates the initially cell-autonomous postsynaptic action of RA to presynaptic partners that send their inputs to the RA-synthesizing neuron. When multiple excitatory synapses on the same dendritic segment experience reduced activity, RA synthesized at these locations could even act synergistically to influence all synapses on this segment, switching RA’s action from a more local to a more global mode. Thus, depending on the location and scale of RA synthesis, RA can potentially alter the strength of a single synapse, a subset of neighboring synapses, or all of the synapses in a dendritic segment. A number of recent studies in the hippocampus and cortex show that neighboring synaptic inputs on the same dendrites tend to have synchronized activity (Kleindienst et al., 2011; Takahashi et al., 2012), and that behaviorally induced synaptic plasticity and spine dynamics exhibit highly structured spatial patterns (Fu et al., 2012; Lai et al., 2012; Makino and Malinow, 2011). Although much more work is required, it will be fascinating to investigate whether RA and possibly other small molecules play an instructive role in sculpting the strength of synaptic inputs that is critical for encoding, processing and storing stimulus-specific information.

5. Involvement of synaptic RA signaling in mental retardation and autism-spectrum disorders (ASDs)

In the past decade, there has been an explosion of reports identifying genes related to synaptogenesis and synaptic function whose mutation, deletion or duplication was implicated in various forms of neuropsychiatric disorders (State and Levitt, 2011; Zoghbi and Bear, 2012). Among these genes, Fmr1, which encodes the protein FMRP, stands out because of the relatively high prevalence of its associated disorder. In human patients, impaired expression of Fmr1, most frequently due to expansion of CGG repeats in the Fmr1 gene and subsequent hypermethylation, causes Fragile-X syndrome (FXS), the most common inherited form of mental retardation that is also associated in some cases with symptoms characteristic of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). FMRP knockout mice exhibit normal baseline synaptic transmission, but display impairments in certain forms of LTP (Larson et al., 2005; Li et al., 2002), and enhancements in mGluR-dependent LTD (Huber et al., 2002). Like RARα, FMRP is a dendritically localized RNA-binding protein that is believed to specifically bind to mRNAs and to regulate their translation (Bassell and Warren, 2008; Laggerbauer et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001). Dysregulated translation and elevated basal protein synthesis are found in Fmr1 knockout neurons (Dolen et al., 2007; Muddashetty et al., 2007). However, whether FMRP is involved in translational regulation during homeostatic plasticity is unknown.

A potential involvement of FMRP in RA-mediated translational regulation was first proposed based on our observation that dendritic RNA granules capable of actively translating GluA1 protein upon RA stimulation are also enriched in FMRP (Fig. 1A and 1B). Indeed, in Fmr1 knockout mice RA-dependent HSP was found to be completely absent whereas the RA-independent late phase of HSP was intact (Soden and Chen, 2010). Since inactivity-dependent RA synthesis still occurs normally in Fmr1 knockout neurons, cellular events downstream of RA were examined. Consistent with FMRP’s role in regulating protein synthesis, RA-induced translational upregulation of various target mRNAs was abolished in the absence of FMRP (Soden and Chen, 2010).

How do FMRP and RA/RARα work together to regulate RA-mediated translation during homeostatic plasticity? One possibility is that in the absence of FMRP, inhibition of protein synthesis of FMRP-bound mRNAs is removed. Elevated levels of basal mRNA translation may produce a “ceiling effect” that prevents further increases in protein synthesis by RA. However, reintroduction into Fmr1 knockout neurons of a mutant form of FMRP (I304N) that suppresses basal AMPA receptor translation failed to restore RA-dependent HSP, suggesting that simply reducing AMPA receptor protein levels through FMRP binding to mRNA is not sufficient to rescue plasticity. Understanding other cellular processes altered in the Fmr1 knockout mouse may shed light on the specific involvement of FMRP in RA signaling. For example, in addition to removal of translational inhibition through the uncoupling of mRNA from FMRP, the activities of MAPK/Erk1/2 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in Fmr1 knockout mice are elevated (Bhakar et al., 2012; Osterweil et al., 2010; Ronesi et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2010). Coincidently, RA has been reported to activate MAPK/Erk as well as PI3K signaling pathways in various cell lines (Ko et al., 2007; Masia et al., 2007; Uruno et al., 2005), making these pathways likely candidate for linking FMRP and RA functions. Although no direct binding of FMRP to RARα was observed (Soden and Chen, 2010), it is possible that they interact by binding to the same RNA molecules. Deciphering the functional interplay between FMRP and RARα will be a critical step towards understanding the molecular basis of FMRP-mediated translational regulation and the Fmr1 knockout phenotype.

The blockage of HSP in Fmr1 knockout mice and the requirement for FMRP in synaptic RA signaling raise the intriguing possibility that impaired HSP may underlie some symptoms associated with intellectual disability and cognitive dysfunction. Hebbian-type synaptic plasticity is considered the cellular mechanism for learning and memory. Fmr1 knockout mice, as an animal model for Fragile-X mental retardation, have been studied extensively for defects in neuronal function and learning and memory. Indeed, impaired Hebbian-type synaptic plasticity in Fmr1 knockout mice (Huber et al., 2002; Larson et al., 2005) may contribute to their learning deficits (Koekkoek et al., 2005; Mineur et al., 2002; Yan et al., 2004). The newly discovered link between FMRP, HSP and RA-mediated translational regulation of synaptic proteins suggest that FMRP and its regulation of protein synthesis participate in multiple forms of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, though seemingly through distinct mechanisms. These findings provide a new perspective on the phenotype in Fmr1 knockout mice and on the symptoms of human Fragile-X patients. It may explain, for example, the global alterations of neural activity that have been observed in Fmr1 knockout mice and FXS patients (Berry-Kravis, 2002; Yan et al., 2004). Moreover, as we discussed above, although HSP may not participate directly in the cellular processes for memory encoding (e.g. input-specific neural circuitry modification), its contribution to network stability and its influence to neuronal coding capacity through meta-plasticity nonetheless could significantly alter the cognitive function of an organism. Understanding the interplay between these different processes will provide significant further insight into the circuitry underpinning of memory formation as well as synaptic dysfunction in neurological diseases.

6. Summary and Future Directions

Until recently, RA was primarily known as a regulator of nuclear transcription in development. The newly discovered non-transcriptional function of RA in mature neurons represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of the mechanisms underlying RA’s role in the adult brain, and allows us to explore the biological significance of this important molecule under a different light. The established role of RA in HSP through synaptic activity-dependent modulation of local protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites indicates that RA participates actively in cellular processes beyond development, and may potentially influence the cognitive functions of an organism throughout life.

The mere fact that a nuclear signaling molecule and its receptor are also dendritic regulators of synaptic strength is amazing, although it accounts for previous observations that RA synthesis and receptor expression persist far beyond development into adulthood. Future work is needed to understand how the RA-dependent control of synaptic strength relates to the overall properties of neural circuits and to the behavior of a whole animal, as well as how RARα controls synaptic strength as a function of RA and whether this control is important for overall nervous system function. The discovery that RA is more than a developmental morphogen, but also a diffusible mediator of synaptic signaling opens up new avenues to our understanding of synaptic communication in the brain, and fits well into the emerging concept that developmental signaling mechanisms are reused in adult organisms in multifarious ways for a variety of functions.

Highlights.

Retinoic acid (RA) is a potent regulator for synaptic strength in mature neurons.

RA mediates homeostatic synaptic plasticity.

RA acts as a synaptic activity sensor.

RA receptor RARα acts as an mRNA-binding protein and translational repressor.

Defective RA synaptic signaling may underlie certain neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by research grants R01 MH091193 and P50MH086403 to L.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham WC, Bear MF. Metaplasticity: the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:126–130. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:803–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoto J, Nam CI, Poon MM, Ting P, Chen L. Synaptic signaling by all-trans retinoic acid in homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;60:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie EC, Stellwagen D, Morishita W, Bresnahan JC, Ha BK, Von Zastrow M, Beattie MS, Malenka RC. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science. 2002;295:2282–2285. doi: 10.1126/science.1067859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren K, McCaffery P, Drager U, Forehand CJ. Differential distribution of retinoic acid synthesis in the chicken embryo as determined by immunolocalization of the retinoic acid synthetic enzyme, RALDH-2. Dev Biol. 1999;210:288–304. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis E. Epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:724–728. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakar AL, Dolen G, Bear MF. The pathophysiology of fragile X (and what it teaches us about synapses) Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:417–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco T, Staras K, Darcy KJ, Goda Y. Local dendritic activity sets release probability at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2008;59:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, McCaffery P. The neurobiology of retinoic acid in affective disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:315–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Napoli JL. All-trans-retinoic acid stimulates translation and induces spine formation in hippocampal neurons through a membrane-associated RARalpha. Faseb J. 2008;22:236–245. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8739com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated metaplasticity in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2004;43:871–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang MY, Misner D, Kempermann G, Schikorski T, Giguere V, Sucov HM, Gage FH, Stevens CF, Evans RM. An essential role for retinoid receptors RARbeta and RXRgamma in long-term potentiation and depression. Neuron. 1998;21:1353–1361. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco S, Diaz G, Stancampiano R, Diana A, Carta M, Curreli R, Sarais L, Fadda F. Vitamin A deficiency produces spatial learning and memory impairment in rats. Neuroscience. 2002;115:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:307–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW, Bezprozvanny I. Maintaining the stability of neural function: a homeostatic hypothesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:847–869. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev S, Adler AJ, Edwards RB. Adult rabbit brain synthesizes retinoic acid. Brain Res. 1993;632:325–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91170-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Davis GW. The schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin controls synaptic homeostasis. Science. 2009;326:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1179685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Tong A, Davis GW. Snapin is critical for presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8716–8724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5465-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolen G, Osterweil E, Rao BS, Smith GB, Auerbach BD, Chattarji S, Bear MF. Correction of fragile X syndrome in mice. Neuron. 2007;56:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echegoyen J, Neu A, Graber KD, Soltesz I. Homeostatic plasticity studied using in vivo hippocampal activity-blockade: synaptic scaling, intrinsic plasticity and age-dependence. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Kennedy MJ, Goold CP, Marek KW, Davis GW. Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;52:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Pielage J, Davis GW. A presynaptic homeostatic signaling system composed of the Eph receptor, ephexin, Cdc42, and CaV2.1 calcium channels. Neuron. 2009;61:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Yu X, Lu J, Zuo Y. Repetitive motor learning induces coordinated formation of clustered dendritic spines in vivo. Nature. 2012;483:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature10844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Sato T, Kaneko S, Gotoh O, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Osawa K, Kato S, Hamada H. Metabolic inactivation of retinoic acid by a novel P450 differentially expressed in developing mouse embryos. EMBO J. 1997;16:4163–4173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold CP, Davis GW. The BMP ligand Gbb gates the expression of synaptic homeostasis independent of synaptic growth control. Neuron. 2007;56:109–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S, Chambon P. Nuclear receptors enhance our understanding of transcription regulation. Trends Genet. 1988;4:309–314. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Timlin JA, Roysam B, McNaughton BL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Mapping behaviorally relevant neural circuits with immediate-early gene expression. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Zhang D, Jarzylo L, Huganir RL, Man HY. Homeostatic regulation of AMPA receptor expression at single hippocampal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:775–780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706447105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Wei H, Zhang X, Chen K, Li Y, Qu P, Chen J, Liu Y, Yang L, Li T. Changes in the expression and subcellular localization of RARalpha in the rat hippocampus during postnatal development. Brain Res. 2008;1227:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Trevino M, He K, Ardiles A, Pasquale R, Guo Y, Palacios A, Huganir R, Kirkwood A. Pull-push neuromodulation of LTP and LTD enables bidirectional experience-induced synaptic scaling in visual cortex. Neuron. 2012;73:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7746–7750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata K, Sun Q, Turrigiano GG. Rapid synaptic scaling induced by changes in postsynaptic firing. Neuron. 2008;57:819–826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakawich SK, Nasser HB, Strong MJ, McCartney AJ, Perez AS, Rakesh N, Carruthers CJ, Sutton MA. Local presynaptic activity gates homeostatic changes in presynaptic function driven by dendritic BDNF synthesis. Neuron. 2010;68:1143–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju W, Morishita W, Tsui J, Gaietta G, Deerinck TJ, Adams SR, Garner CC, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH, Malenka RC. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic synthesis and trafficking of AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:244–253. doi: 10.1038/nn1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi R, Yu J, Honda J, Hu J, Whitelegge J, Ping P, Wiita P, Bok D, Sun H. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Govindarajan A, Jung HY, Kang H, Tonegawa S. Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2004;116:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E, Dever TE. Biochemical mechanisms for translational regulation in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:931–942. doi: 10.1038/nrn1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst T, Winnubst J, Roth-Alpermann C, Bonhoeffer T, Lohmann C. Activity-dependent clustering of functional synaptic inputs on developing hippocampal dendrites. Neuron. 2011;72:1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Yun CY, Lee JS, Kim JH, Kim IS. p38 MAPK and ERK activation by 9-cis-retinoic acid induces chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR2 expression in human monocytic THP-1 cells. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39:129–138. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koekkoek SK, Yamaguchi K, Milojkovic BA, Dortland BR, Ruigrok TJ, Maex R, De Graaf W, Smit AE, VanderWerf F, Bakker CE, Willemsen R, Ikeda T, Kakizawa S, Onodera K, Nelson DL, Mientjes E, Joosten M, De Schutter E, Oostra BA, Ito M, De Zeeuw CI. Deletion of FMR1 in Purkinje cells enhances parallel fiber LTD, enlarges spines, and attenuates cerebellar eyelid conditioning in Fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2005;47:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel W, Kastner P, Chambon P. Differential expression of retinoid receptors in the adult mouse central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1999;89:1291–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. Neuronal RNA granules: a link between RNA localization and stimulation-dependent translation. Neuron. 2001;32:683–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laggerbauer B, Ostareck D, Keidel EM, Ostareck-Lederer A, Fischer U. Evidence that fragile X mental retardation protein is a negative regulator of translation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:329–338. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CS, Franke TF, Gan WB. Opposite effects of fear conditioning and extinction on dendritic spine remodelling. Nature. 2012;483:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMantia AS. Forebrain induction, retinoic acid, and vulnerability to schizophrenia: insights from molecular and genetic analysis in developing mice. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Bailey SJ. Role of retinoid signalling in the adult brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:275–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Jessen RE, Kim D, Fine AK, du Hoffmann J. Age-dependent and selective impairment of long-term potentiation in the anterior piriform cortex of mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9460–9469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2638-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–959. doi: 10.1038/35016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Yasuda R, Ehlers MD. Metaplasticity at single glutamatergic synapses. Neuron. 2010;66:859–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Pelletier MR, Perez Velazquez JL, Carlen PL. Reduced cortical synaptic plasticity and GluR1 expression associated with fragile X mental retardation protein deficiency. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:138–151. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Ku L, Wilkinson KD, Warren ST, Feng Y. The fragile X mental retardation protein inhibits translation via interacting with mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2276–2283. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lufkin T, Lohnes D, Mark M, Dierich A, Gorry P, Gaub MP, LeMeur M, Chambon P. High postnatal lethality and testis degeneration in retinoic acid receptor alpha mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7225–7229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghsoodi B, Poon MM, Nam CI, Aoto J, Ting P, Chen L. Retinoic acid regulates RARalpha-mediated control of translation in dendritic RNA granules during homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16015–16020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804801105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino H, Malinow R. Compartmentalized versus global synaptic plasticity on dendrites controlled by experience. Neuron. 2011;72:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Wendling O, Dupe V, Mascrez B, Kastner P, Chambon P. A genetic dissection of the retinoid signalling pathway in the mouse. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:609–613. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruvada P, Baumann CT, Hager GL, Yen PM. Dynamic shuttling and intranuclear mobility of nuclear hormone receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12425–12432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masia S, Alvarez S, de Lera AR, Barettino D. Rapid, nongenomic actions of retinoic acid on phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling pathway mediated by the retinoic acid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2391–2402. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery P, Drager UC. Retinoic acid synthesis in the developing retina. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;328:181–190. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2904-0_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Sluyter F, de Wit S, Oostra BA, Crusio WE. Behavioral and neuroanatomical characterization of the Fmr1 knockout mouse. Hippocampus. 2002;12:39–46. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misner DL, Jacobs S, Shimizu Y, de Urquiza AM, Solomin L, Perlmann T, De Luca LM, Stevens CF, Evans RM. Vitamin A deprivation results in reversible loss of hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11714–11719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191369798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muddashetty RS, Kelic S, Gross C, Xu M, Bassell GJ. Dysregulated metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent translation of AMPA receptor and postsynaptic density-95 mRNAs at synapses in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5338–5348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn AC, Nichols RA, Brady MJ, Palfrey HC. Nerve growth factor treatment or cAMP elevation reduces Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III activity in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14265–14272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, McCaffery P, Drager UC, Chambon P, Dolle P. Restricted expression and retinoic acid-induced downregulation of the retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (RALDH-2) gene during mouse development. Mech Dev. 1997;62:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto M, Takeda Y, Uchida S, Mitsuda K, Enomoto H, Saito K, Choi T, Watabe AM, Kobayashi S, Masushige S, Manabe T, Kida S. Dysfunction of the RAR/RXR signaling pathway in the forebrain impairs hippocampal memory and synaptic plasticity. Mol Brain. 2012;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K, Bear MF. Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15616–15627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennimpede T, Cameron DA, MacLean GA, Li H, Abu-Abed S, Petkovich M. The role of CYP26 enzymes in defining appropriate retinoic acid exposure during embryogenesis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:883–894. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon MM, Chen L. Retinoic acid-gated sequence-specific translational control by RARalpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20303–20308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807740105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray WJ, Bain G, Yao M, Gottlieb DI. CYP26, a novel mammalian cytochrome P450, is induced by retinoic acid and defines a new family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18702–18708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich MM, Wenner P. Sensing and expressing homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi JA, Collins KA, Hays SA, Tsai NP, Guo W, Birnbaum SG, Hu JH, Worley PF, Gibson JR, Huber KM. Disrupted Homer scaffolds mediate abnormal mGluR5 function in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:431–440. S431. doi: 10.1038/nn.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AC, Zolfaghari R. Cytochrome P450s in the regulation of cellular retinoic acid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:65–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarti F, Schroeder J, Aoto J, Chen L. Conditional RARalpha knockout mice reveal acute requirement for retinoic acid and RARalpha in homeostatic plasticity. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:16. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiderer CL, Dobrunz LE, McMahon LL. Novel form of long-term synaptic depression in rat hippocampus induced by activation of alpha 1 adrenergic receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1071–1077. doi: 10.1152/jn.00420.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman EM, Dynes JL, Steward O. Synaptic regulation of translation of dendritic mRNAs. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7143–7146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1796-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol GH, Ziburkus J, Huang S, Song L, Kim IT, Takamiya K, Huganir RL, Lee HK, Kirkwood A. Neuromodulators control the polarity of spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;55:919–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Hoeffer CA, Takayasu Y, Miyawaki T, McBride SM, Klann E, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:694–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3696-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JD, Rumbaugh G, Wu J, Chowdhury S, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2006;52:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soden ME, Chen L. Fragile X protein FMRP is required for homeostatic plasticity and regulation of synaptic strength by retinoic acid. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:16910–16921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3660-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soprano DR, Qin P, Soprano KJ. Retinoic acid receptors and cancers. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:201–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State MW, Levitt P. The conundrums of understanding genetic risks for autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1499–1506. doi: 10.1038/nn.2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Ito HT, Cressy P, Kempf C, Woo JC, Schuman EM. Miniature neurotransmission stabilizes synaptic function via tonic suppression of local dendritic protein synthesis. Cell. 2006;125:785–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Dendritic protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cell. 2006;127:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Taylor AM, Ito HT, Pham A, Schuman EM. Postsynaptic decoding of neural activity: eEF2 as a biochemical sensor coupling miniature synaptic transmission to local protein synthesis. Neuron. 2007;55:648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Wall NR, Aakalu GN, Schuman EM. Regulation of dendritic protein synthesis by miniature synaptic events. Science. 2004;304:1979–1983. doi: 10.1126/science.1096202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Kitamura K, Matsuo N, Mayford M, Kano M, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y. Locally synchronized synaptic inputs. Science. 2012;335:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1210362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasset D, Tora L, Fromental C, Scheer E, Chambon P. Distinct classes of transcriptional activating domains function by different mechanisms. Cell. 1990;62:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90394-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan TC, Lindskog M, Malgaroli A, Tsien RW. LTP and adaptation to inactivity: overlapping mechanisms and implications for metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:156–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan TC, Lindskog M, Tsien RW. Adaptation to synaptic inactivity in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2005;47:725–737. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan TC, Piedras-Renteria ES, Tsien RW. alpha- and betaCaMKII. Inverse regulation by neuronal activity and opposing effects on synaptic strength. Neuron. 2002;36:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Haskell G, Maynard TM, Shatzmiller RA, Lamantia AS. Retinoic acid signaling at sites of plasticity in the mature central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2002;452:228–241. doi: 10.1002/cne.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tora L, Gaub MP, Mader S, Dierich A, Bellard M, Chambon P. Cell-specific activity of a GGTCA half-palindromic oestrogen-responsive element in the chicken ovalbumin gene promoter. EMBO J. 1988a;7:3771–3778. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Turcotte B, Gaub MP, Chambon P. The N-terminal region of the chicken progesterone receptor specifies target gene activation. Nature. 1988b;333:185–188. doi: 10.1038/333185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: local and global mechanisms for stabilizing neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a005736. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG. The self-tuning neuron: synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell. 2008;135:422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uruno A, Sugawara A, Kanatsuka H, Kagechika H, Saito A, Sato K, Kudo M, Takeuchi K, Ito S. Upregulation of nitric oxide production in vascular endothelial cells by all-trans retinoic acid through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Circulation. 2005;112:727–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E, Luo T, Drager UC. Retinoic acid synthesis in the postnatal mouse brain marks distinct developmental stages and functional systems. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1244–1253. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Zhang ZJ, Hintze M, Chen L. Decrease in calcium concentration triggers neuronal retinoic acid synthesis during homeostatic synaptic plasticity. J Neuroscience. 2011 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3964-11.2011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QJ, Asafo-Adjei PK, Arnold HM, Brown RE, Bauchwitz RP. A phenotypic and molecular characterization of the fmr1-tm1Cgr fragile X mouse. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:337–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K, Philpot BD. Regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression and its implications for LTD, LTP, and metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1081–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu LM, Goda Y. Dendritic signalling and homeostatic adaptation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterstrom RH, Lindqvist E, Mata de Urquiza A, Tomac A, Eriksson U, Perlmann T, Olson L. Role of retinoids in the CNS: differential expression of retinoid binding proteins and receptors and evidence for presence of retinoic acid. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:407–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi HY, Bear MF. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with autism and intellectual disabilities. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]