Abstract

We use the Immigrants Admitted to the United States (micro-data) supplemented with special tabulations from the Department of Homeland Security to examine how family reunification impacts the age composition of new immigrant cohorts since 1980. We develop a family migration multiplier measure for the period 1981 to 2009 that improves on prior studies by including immigrants granted legal status under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act and relaxing unrealistic assumptions required by synthetic cohort measures. Results show that every 100 initiating immigrants admitted between 1981–85 sponsored an average of 260 family members; the comparable figure for initiating immigrants for the 1996–2000 cohort is 345 family members. Furthermore, the number of family migrants ages 50 and over rose from 44 to 74 per 100 initiating migrants. The discussion considers the health and welfare implications of late-age immigration in a climate of growing fiscal restraint and an aging native population.

Keywords: Chain migration, family sponsored immigrants, age at admission, immigration multiplier

Introduction

The United States has witnessed major social, economic and demographic changes since the last major overhaul of its immigration laws in 1965. Not only have the numbers of legally admitted immigrants swollen from roughly 500 thousand per year during the early 1980s to over one million annually in recent years (Monger, 2010), but the family reunification emphasis in U.S. immigrant admissions policies have produced formidable visa backlogs for countries that send large numbers of migrants to the United States (Wasem, 2010a) and fueled family-based chain migration (Yu, 2008). Chain migration, the process by which migrants from a particular location join relatives in the same destination, is an important consequence of family reunification entitlements because “each new immigrant becomes a potential immigrant sponsor” (Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1990: 213; Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1986: 291, 309 note 1).

A little noticed consequence of family chain migration is an upward shift in the age structure of recent arrivals. Because most international migrants are in their prime working ages or younger, most immigration studies that consider age focus on the potential of newcomers to forestall population aging in industrial societies. Even in countries with long immigration traditions, however, the rejuvenating effects of migration on the age structure are modest and depend on the ages of new arrivals (UN, 2001). Simply put, as the age at entry of international migrants rises, not only does their reproductive impact via future fertility fall, but so also does their economic contribution via labor force activity. With a few exceptions, age is largely ignored for family unification migrants.

Although the United States has not witnessed protracted below replacement fertility like many OECD countries, its swelling visa backlogs coupled with growing concerns about population aging suggest that age might be considered as a criterion of admission.1 Except for a spate of studies following the 1996 welfare reform act that restricted immigrants’ access to means-tested social benefits (e.g., Friedland and Pankaj, 1997; Fix and Passel, 1999; Treas, 1997), there has been limited attention to changes in late-age immigration as distinct from in-situ aging of the foreign-born population. Two recent descriptive reports by Terrazas (2009) and Batalova (2012) are notable exceptions. Both authors use census and survey data to profile the aging foreign-born population, but can only approximate temporal changes in the number of new immigrant seniors. Surprisingly, the Congressional Research Service and the DHS Office of Immigration Statistics provide limited or no age composition breakdowns for new legal permanent residents (LPRs) in their published reports.2

Accordingly, we use administrative data to examine trends in late-age immigrant flows between 1981 and 2009, a period that covers the most recent surge in U.S. immigration. We use 50 as a lower age threshold for several reasons. First, this age represents approximately two-thirds of average life expectancy, and for most workers, an age when earnings growth slows. Moreover, people who migrate at age 50 or older are likely to experience work history disruption that may adversely affect their prospects for retirement income or other benefits (Treas, 1997; Angel, 2003; Binstock and Jean-Baptiste, 1999). And, with more than half of recently admitted elderly immigrants not proficient in English, linguistic difficulty, together with cultural barriers, may impede obtaining paid work (Espenshade and Fu, 1997; Batalova, 2012). In the United States, eligibility for Social Security and full Medicare benefits requires 40 full quarters of qualified employment, but approximately one-quarter of older immigrants lacks a work history sufficient to qualify for Medicare (Angel, 2003; Friedland and Pankaj, 1997).

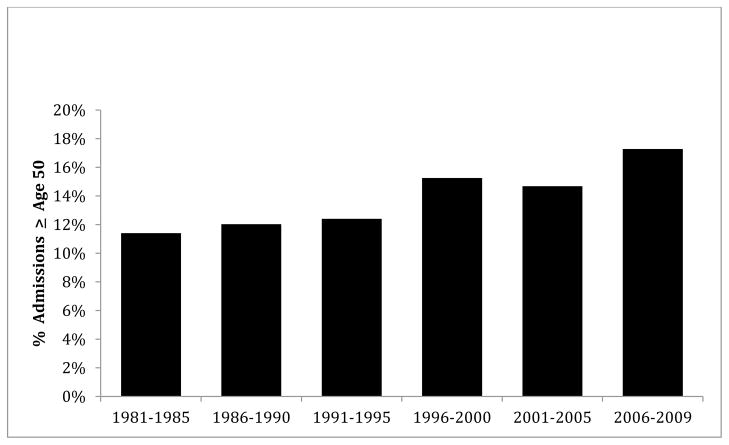

As Figure 1 illustrates, the immigrant cohort share ages 50 and over at admission to the United States increased from about 11 percent for persons legally admitted between 1981 and 1985 to nearly 17 percent for those admitted between 2006 and 2009. We claim that family-sponsored migration is largely responsible for this trend, which appears to be an unintended by-product of adding parents to the family reunification priorities that are exempt from preference, per-country, and worldwide numerical limits (Kennedy, 1966) and, to a lesser extent, the preference categories that permit citizens to sponsor adult siblings. To make our case, we derive estimates for a family migration multiplier, which is a measure of chain migration that reflects the number of additional immigrants sponsored by initiating non-family legal immigrants. Our interest in chain migration is its role as a driver of late-age immigration via activation of family unification entitlements. We focus exclusively on legal immigration because unauthorized aliens in the U.S. cannot sponsor family members for immigration (Wasem, 2010b).

FIGURE 1. Late-Age Immigrants as Percentage of Admissions by 5-Year Cohort, 1981–2009.

Source: Authors’ tabulations from Immigrants Admitted to the United States data file (USDOJ, Immigrants Admitted to the United States, 1981–2000), and Special Tabulations provided by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2010.

Following a brief review of studies about chain migration, we discuss the measure of chain migration developed by Bin Yu (2008), including its strengths and opportunities for refinement. Subsequently we elaborate our refinement of Yu’s measure of chain migration and present estimates for the period 1980 through 2009, including the large cohort granted amnesty under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). Neither Yu nor Jasso and Rosenzweig (1986, 1989) considered IRCA status adjusters in their analyses of chain migration. The final section discusses the social welfare and policy implications of our findings.

Background

The family unification provisions of the 1965 Amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) increased family chain migration in two ways: first, by giving high priority to family reunification in allocating visas; and second, by adding parents of U.S. citizens to the category of immediate relatives exempt from the numerical limits imposed on countries (Kennedy, 1966). Currently about two-thirds of all new legal immigrants enter under family reunification provisions. Of the 1.1 million legal permanent residents admitted in 2009, for example, 66 percent were family-based; of these, 76 percent were immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, and therefore not subject to the preference category, per-country or worldwide caps (USDHS, 2010). Only 13 percent of permanent resident visas issued in 2009 were in conjunction with employment; 16 percent were for asylees and refugees; and the remainder—about 5 percent—were issued for diversity or other criteria (USDHS, 2010).

Immediate relatives, defined as spouses, unmarried dependent children and parents of U.S. citizens, are exempt from annual caps and constitute the majority of family-sponsored migrants. Other sponsored relatives—which include spouses and children of legal permanent residents as well as U.S. citizens’ adult offspring, adult siblings and their respective dependents—not only are subject to category-specific caps, but also to a seven percent per-country maximum of the annual worldwide ceilings in any given year (Wasem, 2010a). That visas are issued according to date of filing and restricted by country ceilings has produced large backlogs for oversubscribed countries, such as Mexico and the Philippines, where wait times from petition to visa granting extend up to a decade or more (Wasem, 2010a: 12).3 As a result of the visa backlogs, thousands of sponsored adult family members age in situ from the date their application is approved until their priority date for receiving a visa.

The exemption of immediate family relatives from the annual caps is particularly relevant for understanding the multiplicative impact of the family reunification provisions of INA. Although legal permanent residents also can sponsor immediate family members, until they become citizens they are limited to sponsoring spouses and dependent children, both of which are charged against annual country limits and subject to visa availability. After naturalization, however, new citizens also can sponsor parents as well as adult offspring and siblings. Illegal immigrants cannot sponsor others for migration (Wasem, 2010b).

If the growth of chain migration is widely acknowledged, its magnitude is the subject of some dispute (Arnold, et al., 1989; Heinberg, et al., 1989; Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1989; 1986; Yu, 2008). With the notable exception of Yu (2008) and Jasso and Rosenzweig (1986, 1989), however, there have been few comprehensive analyses of chain migration. To a large extent, this dearth reflects the lack of suitable data to track the sponsorship behavior of successive immigrant cohorts, let alone cohorts over multiple decades. Existing studies of chain migration exhibit other limitations that compromise their external validity. For example, Arnold and associates (1989) limit their analysis to Korea and the Philippines. Other studies exclude key sponsorship pathways (Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1986, 1990); rely on stated plans to sponsor relatives rather than actual petitions (Arnold et al. 1989); or describe sponsor characteristics ex-post-facto based on cross-sectional data (Heinberg, et al., 1989). Finally, most studies of family sponsorship do not extend beyond 1980, and thus exclude the period during which there were two major revisions to immigration laws that potentially increased chain migration. These include the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which legalized over 2.5 million undocumented migrants, and the 1990 Immigration Act, which raised the worldwide ceilings for capped legal immigrants, including family sponsorship categories subject to numerical limitation (Wasem, 2010a).

Only Jasso and Rosenzweig (1989) and Yu (2008) use demographic methods to derive estimates of family chain migration, but owing to differing assumptions and measures, their results differ. Jasso and Rosenzweig (1989) claim that an initiating nonfamily immigrant subsequently sponsors between 1.2 and 1.4 additional family members. Yu (2008) estimates that chain migration is as high as 4.2 additional persons per initiating immigrant, of which about half (2.1) are immediate family members. Neither study considered the age composition of the sponsored migrants, however.

Using readily available microdata for legal immigrant admissions between 1972 and 1997, Yu (2008) developed an innovative family unification multiplier based on actual LPR admissions. His approach improves over previous methods because it incorporates all forms of family sponsorship and nearly all non-family immigrant pathways to family unification. On the downside, Yu’s (2008) synthetic cohort methodology assumes no cohort or period variation in the processes that contribute to migration, despite known temporal and regional spikes in LPR admissions between 1972 and 1997. Furthermore, Yu ignored the 2.7 million LPRs legalized under IRCA. Although this omission is consistent with his synthetic cohort approach, it inaccurately represented actual LPR admissions during the late 1980s and early 1990s and likely underestimated the magnitude of family chain migration.

Because Yu’s study ended in 1997, his analysis also does not capture the continuing impact of the IRCA regularization process on subsequent generations of family-sponsored immigrants nor that of the higher worldwide ceilings for legal immigration established in 1990. Yu’s analysis also excludes the beneficiaries of the 1997 Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) and the 1998 Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act (HRIFA), which granted legal status to several hundred thousand illegal immigrants. Finally, Yu’s study period ended contemporaneously with the enactment of several major social policy changes that likely impacted family sponsored migration, such as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) and the 1996 welfare reforms, authorized by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). The former broadened the grounds for exclusion of unauthorized immigrants and changed the support requirements for sponsoring family relatives; the latter sharpened the divisions between citizens and legal permanent residents by imposing a five-year moratorium on immigrants’ access to most means-tested welfare benefits, including Medicaid.

Our analysis builds on the strengths of Yu’s approach in conjunction with several refinements that address some limitations of his methodology. First, we relax the assumptions of Yu’s synthetic cohort method by allowing actual fluctuations in both the number and country of origin composition of legal permanent residents. This is important because the source countries of family migrants have changed since 1980 (Wasem, 2010a). Second, we include the 2.7 million IRCA immigrants in the calculations of chain migration because they too can sponsor relatives after acquiring citizenship. Finally, and critical for our interest in late age-immigration, we incorporate a time-varying age component in U.S. legal immigration by simultaneously considering age group and admission cohort.

Data and Methods

Like Yu (2008), we use the Immigrants Admitted to the United States (micro-data) (U.S. Department of Justice (USDOJ) 2007) supplemented with special tabulations from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (USDHS) to examine changes in the age composition of immigrant cohorts since 1981. The microdata file contains records for all LPR admissions between 1981 and 2000, which is the last year included in the final electronic release. These data enumerate all LPR admissions, including persons present in the United States who adjusted their status to permanent resident during those years, with the notable exception of 2.7 million LPRs granted amnesty under the 1986 IRCA legislation (USDOJ, 2007). We augment the Immigrants Admitted data with two sets of summary tabulations: (1) for LPR admissions for the period 2001–2009; and (2) for IRCA legalization admissions for the period 1989–2000. These tabulations were obtained as a custom request from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (USDHS) in order to update and resolve limitations in the Immigrants Admitted files.4

Both the microdata and the custom tabulations contain several items that are necessary to derive age-, cohort- and region-specific measures of chain migration, including year of admission, age (or age group) at admission, visa admission category (detailed or aggregated), and country or region of origin. Unlike microdata files in which each observation represents one new immigrant, the observations in the augmented Immigrants Admitted file represent unique combinations of (admission age * admission year * sponsorship * origin) categories. For each observation, a frequency variable indicates the count of admissions for the given set of age, year, sponsorship, and origin values. Specifically, the analysis file consists of 51,210 observations with (Age*Year*Sponsorship*Origin) count data over 29 years representing 25.5 million legal permanent residents admitted to the United States between 1981 and 2009. Age at admission is grouped into three broad categories: 0–16 (juvenile migrants); 17–49 (working-age migrants); and 50+ (late-age migrants); admission years are aggregated into 5-year cohorts, from 1981–1985; and region of origin is aggregated in to five broad groups: Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America and Oceania, with additional detail for the heavily backlogged countries of Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines. The present analysis, which focuses on the age composition of family sponsored immigrants, does not examine regional or country variation in sponsorship, which is the subject of a separate investigation (identifying reference, 2013).

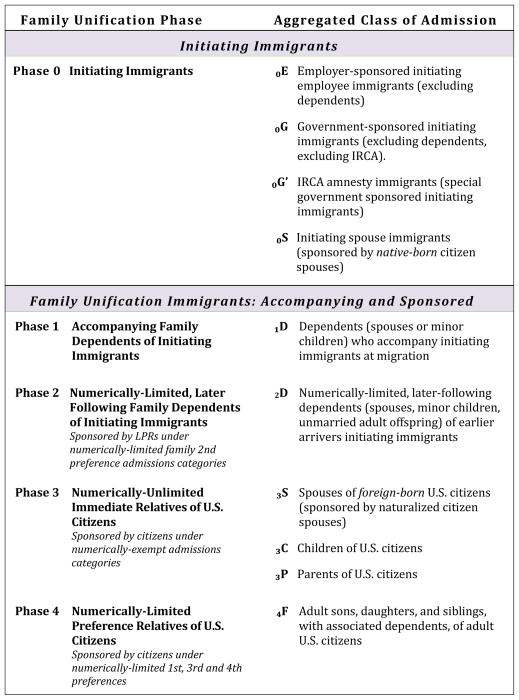

A key requirement for estimating chain migration is the class of admission, which is unavailable in population-based surveys. The United States has a rather complex immigration regime; since 1982, 352 distinct visa classes have been used for LPR admissions. For estimating the family migration multiplier, we extend previous approaches (Yu, 2008) and collapse these classes to 10 categories that represent the major admission classes and the full range of sponsorship possibilities. Importantly, the 10 aggregated admission categories differentiate between (1) initiating and family sponsored immigrants; (2) accompanying versus later-sponsored family unification immigrants; (3) citizen versus LPR sponsored family unification immigrants; and (4) numerically-capped and uncapped admission categories. Figure 2 summarizes the aggregated visa categories used to compute the family migration multiplier.

FIGURE 2. Aggregated Class of Admission by Reunification Migration Phase.

Sources: Adapted from Yu 2005, 2008 (pp. 48–53). Congressional Budget Office, 2010; Monger, 2010; U.S. Dept. of State, 2009.

Because the distinction between initiating immigrants and family unification migrants is central both to the taxonomy and statistical analysis, further elaboration of the operational definitions is warranted. Initiating immigrants refer to all LPRs who are not sponsored by a family migrant, or more generally to nonfamily migrants.5 Stated differently, initiating immigrants represent the first in their families to move to the United States and consequently must either be sponsored by nonfamily entities or they must marry a native-born U.S. citizen. A sponsoring spouse of an initiating immigrant must be a U.S.-born citizen rather than a naturalized citizen. Initiating immigrants include employer-sponsored immigrants, refugees and asylees, diversity lottery beneficiaries, and investors, as well as spouses of native-born U.S. citizens. All are denoted in Figure 2 with a “0” subscript, and the letters E, G, and S designate employer, government and spouse sponsors, respectively. Technically the government does not formally sponsor LPRs, but initiating immigrants who are not sponsored by a U.S. citizen or an employer are admitted under federal authority (Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1989). As such, IRCA initiating immigrants represent a special class of “government sponsored” LPRs.

Legal permanent residents who adjusted their status under the authority of IRCA are not included in the Immigrants Admitted microdata file, but there are several reasons both for including them in our study and for analyzing them as a separate category. First, IRCA beneficiaries have lower naturalization rates and longer durations until achieving naturalized citizenship than non-IRCA LPRs (Rytina, 2002; Baker, 2010). These differences have implications for their ability to sponsor immediate family members. Furthermore, LPRs granted amnesty under IRCA differ in their regional origins, with Mexico the dominant source country (Westat, 1992; Borjas and Tienda, 1993).6 Combined with the country caps, chain migration has direct implications for the swelling visa backlog for Mexico (USDOS, 2011a). Finally, the sheer number of IRCA beneficiaries warrants their inclusion to accurately represent future family unification chain migration.

As Figure 3 shows, between 1986 and 1990 nearly 1.4 million persons adjusted to legal permanent resident status, and an additional 1.3 million did so between 1991 and 1995. For perspective, for every 100 non-IRCA LPRs admitted between 1989 and 1993, an additional 70 IRCA amnesty beneficiaries received LPR status; most of the IRCA status adjustments were completed by 1996. Our interest is in the propensity of earlier immigrants to sponsor family members, but in particular late-age immigrants.

FIGURE 3. Source of Initial Immigrant Admissions, 1981–2009, by 5-Year LPR Cohort.

Source: Source: Authors’ tabulations from Immigrants Admitted to the United States data file (USDOJ, Immigrants Admitted to the United States, 1981–2000), and Special Tabulations provided by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2010.

Notes: The 2006–2009 admission cohort represents four rather than five years. Spouses are foreign-born married to native-born U.S. citizens. Government-sponsored initiating immigrants include both IRCA and non-IRCA admissions, with the IRCA component represented by area above the dashed line.

The lower panel of Figure 2 classifies family unification immigrants, which include all LPRs sponsored by family members who themselves are immigrants (both naturalized citizens and legal resident aliens), or who are family members accompanying an initiating immigrant. We distinguish between four types of family unification immigrants: (1) family dependents who accompany initiating immigrants; (2) later following dependents of LPRs; (3) numerically uncapped immediate relatives of U.S. citizens; and (4) numerically-capped preference relatives of U.S. citizens. Uncapped relatives include alien spouses, unmarried minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens; capped relatives include married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens (1st preference); spouses, minor children, and adult offspring of LPRs (2nd preference); married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens (3rd preference) and siblings of U.S. citizens ages 21 and over (4th preference). The letters D, S, C, P, and F, respectively, designate dependents, spouses, children, parents and other relatives (i.e., siblings and adult sons and daughters) of U.S. citizens. The antecedent subscripts ranging from 1 to 4 indicate the sequencing of the LPR in the migration chain. For example, dependents may accompany the initiating immigrant, or they can follow.

Migrants who are sponsored as spouses of U.S. citizens may be either initiating immigrants (spouses of native-born U.S. citizens, 0S) or family unification immigrants (spouses of foreign-born, naturalized U.S. citizens, 3S). However, because even the most detailed USDHS class of admission information lacks sponsor characteristics, it is not possible to ascertain in either the Immigrants Admitted microdata or the USDHS Special Tabulations whether a migrant’s sponsoring spouse is a native-born versus naturalized U.S. citizen. To resolve this issue, and following Yu (2008:93–94), we assume that the proportion of LPRs sponsored by native-born versus naturalized citizen spouses in each five-year cohort mirrors that of the U.S. population, as estimated in the 2009 American Community Survey (Ruggles, et al., 2010). Specifically, for the married foreign-born population, we assume that the proportion married to native-born versus foreign-born spouses corresponds among LPRs admitted as citizens’ spouses to the proportions of those sponsored by native-born spouses (i.e., initiating spouse immigrants, 0S) versus foreign-born, naturalized spouses (i.e., numerically-unlimited family migrants, 3S).

Family Migration Multiplier

To estimate the magnitude and age-composition of family unification chain migration, we amplify Yu’s (2008) Net Immigration Unification Multiplier, which essentially is a ratio of the number of family-sponsored migrants and initiating migrants.

The two core constructs for estimating family unification migration are initiating immigrants and phases of the migration chain. Only initiating immigrants, designated 0E, 0G, 0G′, or 0S in Figure 2, can start new migration chains. Specifically, the new chains are activated in three ways: (1) when spouses and dependents either accompany the initiating immigrant (family unit migration); (2) when initiating immigrants sponsor spouses, minor children and unmarried adult children, subject to numerical caps; and (3) when initiating immigrants naturalize and activate their family unification entitlements by sponsoring immediate family members as well as adult offspring, siblings and their dependents. All family members sponsored by or who accompany the initiating immigrant are designated family immigrants.7

In Yu’s formulation all family members in a new chain are associated with the initiating immigrant, whether sponsored directly by the initiating immigrant or indirectly by other family immigrants in the chain. Much like Yu, we assume initiating immigrants in a given admission cohort directly sponsor family immigrants; however, as elaborated below, we impose lags to allow for naturalization, which is required for sponsoring exempt family members and adult siblings and offspring, and introduce temporal variation between initiating cohorts and citizen-sponsored family members. Combined, these assumptions allow us to observe the consequences for late-age family migration of variation in the size of LPR cohorts.

The second core construct for deriving measures of chained migration is migration unification phase, which reflects position within a migration chain. In our formulation, phase 0 corresponds to initiating immigrants and migration unification phases 1 through 4 consist of family immigrants. Phase 1 family migrants are the accompanying dependents (1D) of initiating migrants, which include accompanying spouses, children, and in rare cases, other dependent family members. Phase 2 family immigrants are later-following dependents (2D) of initiating immigrants who are admitted under the numerically capped family second preference category.8

Phase 3 family migrants are numerically exempt relatives of U.S. citizens, namely spouses (3S), children (3C), and parents (3P) of U.S. citizens—none of which are subjected to country-specific and worldwide ceilings. Finally, Phase 4 family migrants are numerically capped preference relatives (4F) of adult U.S. citizens. Phase 4 family migrants include married and unmarried adult offspring and siblings of U.S. citizens, along with their accompanying dependents (Figure 2; Monger, 2010, p. 6). There are lengthy visa backlogs for Phase 4 family migrants; since the mid-1990s the visa delays for adult children of citizens have averaged about nine years for most countries. For adult siblings of citizens, admissions during this time routinely reflected petitions submitted a dozen years prior—and for Filipino nationals, sibling admissions were backlogged by 23 years (USDOS, 2011a; 2011b; 2011c). Especially for sponsored adult siblings of citizens from oversubscribed countries (and for all backlogged family preference categories as well), approved applicants “age in place” until their priority date is reached and visas are issued for their migration to the United States.

As a ratio of all family-sponsored to all initiating migrants, Yu’s (2008) Net Immigration Unification Multiplier cannot capture the changing age structure among successive cohorts of legal permanent resident admissions. Therefore, we expand Yu’s formulation by generating a series of age- and cohort-specific family unification multipliers with appropriate lags. Specifically, in order to evaluate how family chain migration influences changes in the age structure of LPRs, we disaggregate all family immigrants by age at admission, distinguishing among dependent youths (<17), prime working age immigrants (17–49) and late-age immigrants (50+). Given that the worldwide ceiling for numerically capped admissions was substantially increased during the observation period and a major legalization added nearly three million immigrants above the worldwide ceilings, we also disaggregate admission cohorts into 5-year cohorts. This modification relaxes the strong synthetic cohort assumptions to better represent the ebbs and flows in LPR admissions.

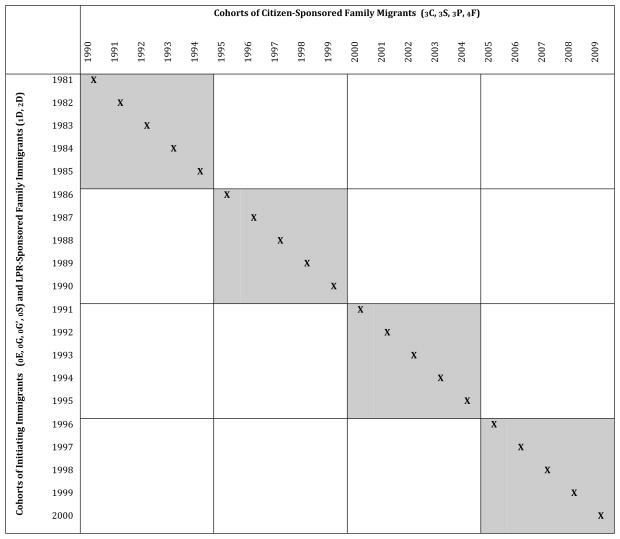

Finally, because unification Phases 3 and 4 require that sponsors attain citizenship, our cohort-specific multiplier formulation permits a more realistic link between initiating immigrant cohorts and subsequent family unification chain migration. This refinement is fundamental because U.S. citizens sponsor the bulk of family unification relatives—more than 85 percent of the family immigrants admitted in 2009, for example (authors’ tabulations based on Wasem, 2010a: 24–26). Figure 4 illustrates the logic of the temporal alignment between annual cohorts of initiating immigrant (vertical axis), LPR-sponsored family migrants (also on vertical axis), and citizen-sponsored family migrants (horizontal axis) for the corresponding five-year cohorts in our analysis.

Figure 4. Cohort Matrix: Initiating Immigrant Cohorts, Generation-Lagged Citizen-Sponsored Cohorts, and 5-Year Admission Cohorts.

Notes: Annual initiating immigrant cohorts (0E, 0G, 0G′, 0S) appear on the vertical axis; accompanying and later-following LPR dependents (1D, 2D) are temporally aligned with these cohorts. X denotes the corresponding annual cohorts of generation-lagged, citizen-sponsored family immigrants (3C, 3S, 3P, 4F), which appear along the horizontal axis. Gray highlights indicate the five-year admission cohorts in FMM estimates.

We follow Yu (2008) in assuming that the vast majority of citizen sponsors (with the exception of U.S. citizen sponsors of spouses) are naturalized rather than native-born. Because U.S. citizen parents confer citizenship to their children automatically (Lee, 2010), we assume that immigrants admitted as the minor children and adult sons and daughters of U.S. citizens were born to (and sponsored by) foreign-born parents. Furthermore, the vast majority of the sponsors of adult siblings and parents are foreign-born persons who migrated and naturalized (Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1990: 230).

Because most family sponsorship entitlements are contingent upon citizenship status, we incorporate a “gestation lag” that allows initiating immigrants time to naturalize, which requires a minimum of five years of U.S. residence, so that the initiating immigrants in our model indeed are eligible to sponsor relatives (Jasso and Rosenzweig 1989: 868).9 Drawing on published naturalization data (Lee, 2010), we assign a lag of nine years between initiating immigrant cohorts and future cohorts of sponsored relatives. Eight years reflects the typical time spent in LPR status prior to naturalization,10 and the ninth year represents the time needed to process the sponsored family members’ visa petitions (Wasem, 2012: 14, 22; Heinberg, et al., 1989: 867).

Employing an “immigrant generation cohort approach” that others (Park and Myers, 2010; Smith, 2003) have used to model mobility with cross-sectional data, we incorporate a nine-year sponsorship generation lag into the Family Migration Multiplier. Specifically, we adjust the cohorts of citizen-sponsored family immigrants to correspond with one sponsorship generation beyond the initiating immigrant cohort. The realignment of cohorts depicted in Figure 4 represents an important extension of prior research about family chain migration given the wide fluctuations in LPR cohorts since 1981.

Expressed in formulaic terms, we estimate the age- and cohort-specific family chain migration multiplier as

where the terms in the numerator represent the counts of specific types of sponsored family migrants and the terms in the denominator represent the counts of each type of initiating immigrant. Specifically, 0E, 0G, 0G′, and 0S denominator terms are employer sponsored, government sponsored and spouse initiating immigrants. In the numerator are initiating immigrants’ accompanying family dependents (1D); initiating immigrants’ numerically capped, later-following family dependents (2D); numerically uncapped spouses, children and parents of U.S. citizens (3S, 3C, 3P); and adult offspring and siblings (with their respective dependents) of citizens (4F).11

Subscript j denotes the three age groups at admission (<17, 17–49 and 50+) among family unification immigrants. Subscript j′, which is applied to the initiating immigrant terms, indicates all ages. Subscripts t and t′ reflect five-year admission cohorts corresponding, respectively, to the early and later stages of the migration chain. For initiating immigrants and Phase 1 and Phase 2 family migrants, admission cohort t consists of one of the following cohorts: 1981–1985, 1986–1990, 1991–1995, or 1996–2000. Subscript t′ is applied to Phase 3 and Phase 4 citizen-sponsored family migrants to approximate the naturalization lag and eligibility for citizen-based sponsorship by initiating immigrants from cohort t such that t′ = t + 9.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the data corresponding to the initiating immigrant admission categories according to age at arrival. Because the family migration multiplier includes terms that are lagged by nine years, the final cohort years for which the multiplier can be calculated are 1996–2000; accordingly, Table 1 concludes with that cohort. Between 1981 and 2000 the share of initiating immigrants ages 50 and over rose from eight to 11 percent (bottom row), but the average conceals large differences by class of admission. The share of late-age LPRs was relatively stable over the period for employer and spouse admission categories, but among government sponsored humanitarian LPRs, the share of late-age immigrants rose from 10 to 18 percent. Late-age migrants comprised between six and ten percent of IRCA LPRs, and despite the large sizes of the amnesty cohorts, they represent a smaller share of government sponsored immigrants ages 50 and over. Specifically, of the 602 thousand late-age LPRs admitted between 1981 and 2000, nearly half were refugees and asylees, 31 percent were IRCA status adjusters and the remainder was employer sponsored and spouses.

TABLE 1.

Initiating Immigrants (0E, 0S, 0G, and 0G′) Admitted from 1981 to 2000 by Age at Admission, Aggregated Class of Admission, and 5-Year LPR Cohort (%)

| Class of Admission and Age at Admission | 5-Year New Immigrant Cohorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | |

| Employer-Sponsored | ||||

| Employees [0E] | (n=120,321) | (n=121,801) | (n=255,816) | (n=196,935) |

| 0 – 16 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| 17 – 49 | 89.5 | 89.4 | 89.9 | 90.7 |

| 50 + | 10.5 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 9.3 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Spouses of Native-Born | ||||

| US Citizens [0S] | (n=293,255) | (n=326,503) | (n=257,506) | (n=348,429) |

| 0 – 16 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 17 – 49 | 95.9 | 96.2 | 95.3 | 95.5 |

| 50 + | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Government-Sponsored [0G] | ||||

| (excluding IRCA admissions) | (n=475,454) | (n=427,266) | (n=542,874) | (n=428,395) |

| 0 – 16 | 25.2 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 5.1 |

| 17 – 49 | 64.4 | 76.4 | 73.9 | 76.7 |

| 50 + | 10.5 | 15.2 | 18.8 | 18.2 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| IRCA Admissions [0G′] | ||||

| (n=1,362,780) | (n=1,319,441) | (n=5,417) | ||

| 0 – 16 | NA | 9.6 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 17 – 49 | -- | 82.3 | 92.9 | 88.8 |

| 50 + | -- | 8.1 | 5.8 | 10.1 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Total, Initiating | ||||

| Immigrants | (n=889,030) | (n=2,238,350) | (n=2,375,637) | (n=979,176) |

| 0 – 16 | 13.5 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| 17 – 49 | 78.2 | 83.6 | 88.5 | 86.3 |

| 50 + | 8.3 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 11.5 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

Source: Authors’ tabulations from Immigrants Admitted to the United States data file (USDOJ, Immigrants Admitted to the United States, 1981–2000), and Special Tabulations provided by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2010.

Note: Percentages do not total 100 because of rounding.

Late–age migrants comprised between five and seven percent of relatives who accompany an initiating migrant during the two-decade observation period; this share increased over time, albeit not monotonically (Table 2, upper panel). Among accompanying dependents of LPRs, those ages 50 and over increased 88 percent between the first and second half of the 1980s, and 116 percent between the 1986–1990 and the 1991–1995 LPR cohorts. Most of this change reflects the doubling of the accompanying family dependent cohorts after 1990, when the worldwide ceiling for numerically capped LPRs was raised. The share of late-age accompanying family dependents was similar for the 1986–1990 and the 1996–2000 LPR cohorts; however, largely owing to the higher ceilings for all preference categories the absolute number rose about 38 percent.

TABLE 2.

Accompanying Dependents (1D) and Later-Following Family Dependents of LPRs (2D): 1981 to 2000 by 5-Year LPR Cohort and Age at Admission (%)

| Family Admission Class and Age at Admission | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981–1985 | 1986–1990 | 1991–1995 | 1996–2000 | |

|

Accompanying Dependents (1D)

| ||||

| 0–16 | 54.4 | 49.9 | 45.6 | 42.5 |

| 17–49 | 41.1 | 43.7 | 47.3 | 51.1 |

| 50+ | 4.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 6.5 |

| Total % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (n) | (310,823) | (403,585) | (808,219) | (558,490) |

|

Later Following Dependents (2D)

| ||||

| 0–16 | 25.9 | 25.9 | 35.0 | 37.7 |

| 17–49 | 71.5 | 71.8 | 62.3 | 58.5 |

| 50+ | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.8 |

| Total % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (n) | (569,611) | (545,299) | (617,194) | (614,585) |

Source: Same as Table 1.

Note: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

The cohort size of later-following LPR family dependents also increased since 1980 (lower panel), but less dramatically compared with accompanying dependents, and over time the cohort sizes of accompanying and later-following LPR dependents converged. Late-age dependents comprise a smaller share of later following dependents compared with those who accompany the initiating immigrants. For example, approximately 6.5 percent of accompanying dependents admitted between 1996 and 2000 were age 50 and above compared with less than four percent of later-following family members (approximately 23 thousand new immigrants). During the 1990s, over 133 thousand dependent family members (both accompanying and later-following) of new immigrants were ages 50 and over.

Late-age immigration is most prevalent among sponsored immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Between 1990 and 2009, nearly five million immediate relatives of U.S. citizens obtained LPR status, of which about one-in-three qualified as late-age migrants (Table 3, bottom panel). The numbers of late-age immigrants among immediate relatives of adult U.S. citizens is noteworthy both because of inter-cohort growth rates and because these family sponsorship categories are not subject to numerical caps. For perspective, the 1.6 million immediate family members admitted between 2005 and 2009 (which in our model is sponsored by the 1996–2000 initiating cohort) represents an increase of 80 percent in the number of exempt family members admitted between 1990 and 1994 (which in our model is sponsored by the 1981–1985 initiating cohort). Unlike the numerically capped admission classes, the surge in sponsorship of immediate family relatives cannot be attributed to the higher worldwide ceilings established by the 1990 Immigration Act.

TABLE 3.

Numerically Exempt Immediate Relatives of Adult U.S. Citizens (3S, 3C and 3P) Admitted between 1990 and 2009 by Aggregated Class of Admission, 5-Year LPR Cohort and Age at Admission (%)

| Family Admission Class and Age at Admission |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2009 | |

| Spouses (3S) | ||||

| 0–16 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 17–49 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.1 | 93.4 |

| 50+ | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 6.5 |

| Subtotal % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Subtotal (n) | (416,274) | (434,047) | (624,431) | (665,835) |

|

| ||||

| Children (3C) | ||||

| 0–16 | 74.3 | 71.3 | 65.3 | 63.9 |

| 17–49 | 25.7 | 28.7 | 34.7 | 36.1 |

| 50+ | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Subtotal % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Subtotal (n) | (193,265) | (264,124) | (332,987) | (424,686) |

|

| ||||

| Parents (3P) | ||||

| 0–16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 17–49 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 8.3 |

| 50+ | 93.6 | 92.7 | 92.3 | 91.7 |

| Subtotal % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Subtotal (n) | (307,558) | (311,728) | (387,667) | (559,924) |

|

| ||||

| All | ||||

| 0–16 | 15.7 | 18.7 | 16.2 | 16.5 |

| 17–49 | 50.9 | 50.8 | 54.9 | 49.8 |

| 50+ | 33.4 | 30.5 | 28.9 | 33.7 |

| Total % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Total (n) | (917,097) | (1,009,899) | (1,345,085) | (1,650,445) |

Source: Same as Table 1

Note: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Table 3 confirms that sponsored parents of U.S. citizens are a key driver of late-age immigration: across the four admission cohorts, parents comprised between 29 and 34 percent of immediate relatives. Growth of the cohort size of sponsored parents was flat between 1980 and the early 1990s, but rose 24 percent between the 1995–1999 and 2000–2004 admission cohorts, and 44 percent over the next decade. Only two mechanisms can account for the rise in late-age immigration associated with parent sponsorship: (1) naturalization of earlier admitted LPRs, who subsequently sponsor their elderly parents and (2) U.S.-born children of foreign-born parents who are eligible to petition for their parents after reaching age 21. With available data it is not possible to disentangle these two mechanisms, but we expect that the latter is tiny because children eligible to sponsor parents between 2006 and 2009—the last year of the period we analyze—were born between 1985 and 1988—at the peak of the IRCA legalization program, when there would have been little need for so-called “anchor babies” to sponsor their parents (see discussion by Huang, 2008).12

Late-age immigration also rose among numerically capped preference relatives of U.S. citizens, which include their adult children as well as siblings and their own dependents. The ceiling on this category stabilized the total number admitted at just over 100 thousand per year, but the share of preference relatives ages 50 and over rose steadily over successive cohorts—from 12 percent of all preference relatives admitted between 1990 and 1994 to 19 percent of preference relatives admitted between 2005 and 2009 (Table 4). Because of aging in place, the country of origin visa backlogs contribute to the rise in late-age immigrants admitted under the capped family preference categories.

TABLE 4.

Numerically Capped Preference Relatives of U.S. Citizens [4F] Admitted between 1990 and 2009 by 5-Year LPR Cohort and Age at Admission (%)

| Age at Admission | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–16 | 31.2 | 27.9 | 24.3 | 23.1 |

| 17–49 | 57.1 | 58.3 | 59.6 | 57.9 |

| 50+ | 11.7 | 13.8 | 16.2 | 19.0 |

| Total % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Total (n) | (503,031) | (515,642) | (557,479) | (568,610) |

Source: Same as Table 1.

Notes: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding. Citizen-sponsored family preference admissions consist of U.S. citizens’ adult sons and daughters, with associated dependents (first and third preferences), and adult citizens’ siblings, also with dependents (fourth preference).

These descriptive tabulations provide insight into the workings of family chain migration and how sponsorship is associated with the increases in the LPR admissions at ages 50 and over. To estimate the compounding of late-age LPR admissions via chain migration, we estimate the family migration multiplier by age for the four most recent initiating cohorts (Table 5). The 1981–1985 LPR cohort (first row) includes nearly 900 thousand initiating immigrants who are associated with over 2.3 million LPRs admitted as family unification migrants. The index values in the last column imply that every 100 initiating immigrants admitted during that five-year period sponsored an average of 259 family members; by comparison, among initiating immigrants admitted between 1996 and 2000, every 100 initiating immigrants sponsored 346 family members. Furthermore, the number of family migrants ages 50 and over (shaded column) rose from 44 to 74 per 100 initiating migrants. This represents a sizable increase because the volume of immigration rose appreciably during this period, and especially after the higher worldwide ceilings for numerically capped preference categories went into effect.

TABLE 5.

Summary of Family Migration Multipliers for Worldwide Origins by Age at Admission and 5-Year Initiating Immigrant Cohort, 1981–2000

| Initiating Cohort | Family Immigrants | Initiating Immigrants |

Family Migration Multipliers

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <17 | Age 17–49 | Age 50+ | All Ages | |||

| 1981–1985 | 2,300,562 | 889,030 | 0.70 | 1.45 | 0.44 | 2.59 |

| 1986–1990 | 2,474,425 | 2,238,350 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 1.11 |

| 1991–1995 | 3,327,977 | 2,375,637 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 1.40 |

| 1996–2000 | 3,392,130 | 979,176 | 0.89 | 1.83 | 0.74 | 3.46 |

| Total | 11,495,094 | 6,482,193 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.32 | 1.77 |

Source: Same as Table 1

Notes: Because of a typical 9-year lag between permanent residence and naturalization, which is a precondition for sponsoring numerically exempt immediate relatives and some family preference relatives, the 3S, 3C, 3P, and 4F cohorts are advanced by nine years; multipliers reflect that the 1981–1985 initiating cohort corresponds to 1990–1994 3S, 3C, 3P, and 4F family admissions, etc.

The dip in the family multiplier values associated with the 1986–1990 and the 1991–1995 LPR cohorts poses somewhat of a methodological challenge because the index appears to be sensitive to the size of the initiating immigrant cohort. The surge in LPR admissions associated with the IRCA legalization program increased the denominator of the multiplier for the 1986–1990 and 1991–1995 initiating cohorts; consequently, 0G values for these periods were more than doubled. An additional reason for the relatively low migration multipliers for the IRCA cohorts reflects the large representation of Mexicans among the legalized population (Rytina, 2002). As Baker observes (2007, 2010), the naturalization behavior of Mexicans differs in that they exhibit a lower propensity to become U.S. citizens and experience longer waiting times to acquiring citizenship. Because the family sponsorship opportunities available to LPRs are far more limited than those available to citizens, this factor also will have depressed the migration multiplier for the LPR cohorts during the observation period.

The number of family LPRs associated with both IRCA-augmented initiating immigrant cohorts grew nonetheless—at first modestly from 2.3 to 2.5 million (see column 2, Table 5), and then more robustly, rising from 2.5 to 3.3 million family migrants associated with the 1991–1995 initiating immigrants. Despite the relatively smaller index value, family migration multiplier values for IRCA-era family migration in fact represent large pools of family immigrants because each reflects a multiplicative effect applied to a massive cohort of initiating immigrants. For example, even the small late-age migration multipliers of 0.19 and 0.23 applied to initiating immigrant cohorts of 2.2 and 2.4 million represent, respectively, late-age cohorts of more than 400 and 550 thousand migrants sponsored by IRCA-era LPRs.

Limitations

Although our approach to family chain migration has overcome several limitations of prior studies, several limitations remain, which, in the main, render our findings conservative. First, the results represent first-order age impacts associated with chain migration because we, like prior analysts using cross-sectional cohort data, cannot directly link earlier immigrants with their sponsored relatives. Therefore, we use information from detailed visa codes to infer these ties and, like prior analysts, we assume that initiating immigrants directly sponsor relatives comprising subsequent links in the migration chain. Our estimates of family chain migration are likely to be conservative to the extent that they cannot incorporate approved petitions for family sponsored migrants in the visa queues; however, our inability to consider emigration and mortality introduces bias in the opposite direction by exaggerating the denominator relative to the numerator.

A second limitation concerns the assumptions about spouses. Because the Immigrants Admitted data lack information about the nativity of citizens who sponsor spouses for immigration, following Yu (2008), we assume that the proportions of native-born versus naturalized sponsoring citizen spouses mirror the population proportions of married, foreign-born persons with native-born versus foreign-born spouses. Using the cross-sectional admission data, it is not possible to incorporate possible relationship formation or dissolution (as well as emigration and mortality) among the foreign-born population subsequent to migration. Whether these assumptions and omissions introduce upward or downward bias is unclear, however.

Third, because the Immigrants Admitted data lack information about the sponsor’s year of admission, we assume that LPR accompanying and later following relatives migrate contemporaneously to the corresponding initiating immigrants. This source of bias is likely to be small overall, but may be significant for some of the countries with large visa backlogs because family members follow rather than accompany the initiating immigrant. Finally, our use of a nine-year lag to represent time to naturalization, which is required for initiating immigrants to become citizens and use family sponsorship entitlements, relies on median years to naturalization (Lee, 2010). This estimate is based only on those immigrants who do naturalize, and it does not reflect annual or regional variations in naturalization rates. Thus, the lag may be too long for Asian immigrants and too short for Mexican immigrants (Lee, 2010). Although our approach is more realistic than the synthetic cohort formulation, our future work focused on variations by region of origin should consider the sensitivity of this lag and its implications for family chain migration.

Summary and Policy Implications

Because international migration is presumed to attenuate population aging in developed nations, there has been scant attention to the age composition of new immigrants. This omission is striking for the United States, which gives priority to family unification over employment and humanitarian based admissions, does not impose age caps on new immigrants and sets a low income threshold for sponsorship of family relatives—(125% of poverty including the new LPRs). Furthermore, all citizens—both naturalized and U.S.-born—are allowed to sponsor immediate relatives, including elderly parents, beyond the statutory annual worldwide caps.

To investigate how admission policies are responsible for the rise in late-age immigration since 1981, we portray family unification immigration as a multiplicative chain migration process. Our multiplier index simultaneously incorporates variation in cohort size and sponsorship with approximate naturalization lags required for sponsorship of exempt family members. By allowing for changes in the size of initiating cohorts, our formulation relaxes the strong assumptions that undergird the synthetic cohort approach used in earlier estimates. In addition, we extend by a decade the time frame prior researchers used to estimate chain migration, and include the large cohort of IRCA legalization beneficiaries in our calculations.

Results show that the cohort share of late-age immigration rose over time, and was mainly driven by government-sponsored, non-IRCA LPRs among initiating migrants, and by parents of U.S. citizens among family-sponsored immigrants. The multiplier index implies that every 100 initiating immigrants from the 1981–1985 admission cohort sponsored an average of 260 family members over the observation period. By comparison, every 100 initiating immigrants from the 1996–2000 LPR cohort sponsored an average 345 family members. Late-age migrants comprised about one-third of the exempt family members admitted between 2005 and 2009—most of them parents (Table 3)—and almost 20 percent of capped relatives (Table 4).

Age has not been an explicit consideration in the admission of legal permanent residents, except as required to distinguish between minors and others. The social and economic significance of the gradual rise in late-age immigration at a time of shrinking safety nets and rising anti-immigrant sentiment depends on the living arrangements of sponsored seniors; on the likelihood that they work and for how long; and whether sponsors assume financial responsibility for newcomers until naturalization, as required by IIRIRA. On the first point, several studies indicate that older immigrants, including those who arrived over age 50, are more likely than comparable natives to live in extended households (Angel, et al. 1999; 2000). As such, families shoulder many of the income support and service needs of late-age immigrants, but more research is needed to evaluate the costs of program participation levels of late-age immigrants who live with their sponsors and those who do not. This goes beyond documenting differences in eligibility and program participation rates between natives and immigrants and between LPRs who arrived before and after the 1996 welfare and immigration reforms, which has been the focus of most research about elderly immigrants (Nam, 2012; Van Hook, 2003).

On the second point, Borjas (2011) claims that the 10-year employment requirement to qualify for Social Security and Medicare is a powerful incentive for late-age immigrants to remain in the labor force at higher than natives; however, he acknowledges that the Social Security ineligibility rate for late-age immigrants rose between 1960 and 2000. In the post Great Recession labor market, late-age immigrants may encounter even greater difficulty qualifying for employment-linked benefits. This is a second empirical question warranting further research in light of the rise in late-age immigration and weak labor markets in the wake of the Great Recession. The costs and benefits of late-age immigration depend not only on whether late-age immigrants earn eligibility for benefits through employment and/or naturalization (Van Hook, 2003), but also on their aggregate contributions relative to claims. To our knowledge, this question has not been addressed in a way that considers the significance of age-at-arrival for the cost-benefit equation.

Changing sponsorship requirements—the third point noted above—also have implications for the economic significance of late-age immigration. Three changes were particularly consequential for late-age immigrants. First, PRWORA closed a huge loophole in the Social Security provisions that allowed late-age immigrants to qualify for Supplemental Security Income on the basis of age and low-income rather than disability (Friedland and Pankaj, 1997; Fix, Passel and Zimmerman, 1996). Second, PRWORA imposed a five-year moratorium on access to means-tested programs on most legal immigrants arriving after August 22, 1996, but exempted refugees, immigrants who have served or whose family has served in the armed forces, and LPRs whose spouse or parent has a long U.S. work history (NILC, 2002, 2009; Ambegaokar and Blazer, 2011).13 Third, IIRIRA requires sponsors to sign a legally binding affidavit (USCIS Form I-864) promising to support their sponsored relatives as of December 1997 and requires that sponsors’ income be considered in determining immigrants’ eligibility for means-tested benefits until they become citizens (Huang, 2008; NILC, 2009).14

For migrants of limited means, these reforms appear to have shifted the source of transfer payments from the more generous SSI program to other forms of public income support. Huang (2008) claims that IIRIRA made it more difficult for recent immigrants to establish income eligibility for public benefits even after the expiration of the 5-year moratorium imposed by PRWORA. Using data collected before the 1996 immigration and welfare reforms, Angel (2003) noted that Medicaid was a major source of health care for seniors who immigrated at advanced ages. Under current law legal U.S. immigrants are barred from Medicare benefits until they qualify for Social Security, which is less likely for LPRs who arrive at advanced ages as compared with prime-age workers, especially for those with limited skill and English-language profiles (Batalova, 2012; Espenshade and Fu, 1997). After five years of residence, Medicaid can be an alternative health care insurance for low-income seniors who do not qualify for Medicare, provided they meet stringent income criteria and deeming practices, which vary across states (Ambegaokar and Blazer, 2011).

The 2005 Deficit Reduction Act requiring citizenship documentation for Medicaid did not change eligibility for noncitizens (NILC, 2006); however, the higher administrative requirements resulted in higher levels of unmet need, according to the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (2007). For seniors who do not qualify for Medicaid, either because of sponsor income deeming or length of U.S. residence, there are few private insurance options. Smolka and associates (2012) report that nearly 9 million adults ages 50–64 lacked health insurance in 2010 and that coverage for this age group fell between 2000 and 2010. Furthermore, they report that over one-in-five applications for health insurance for this age group are denied, which implies that costs for Medicaid and other safety net programs could rise as growing numbers become eligible for these public insurance options.

That private health insurance plans for seniors are in short supply (Smolka et al., 2012) may inadvertently raise the costs of health care for late-age immigrants, who will have to rely on emergency services to meet their health care needs. Choi (2010) examined access to health care among older immigrants (including late-life arrivals) using longitudinal data. Based on evidence that over time foreign-born seniors were less likely than natives to have private insurance, Choi recommends policies to expand affordable health insurance options in order to prevent late-life immigrants from having to rely on more expensive health care solutions, such as emergency services. However, in light of continued resistance to implementation of the Affordable Care Act, there does not appear to be much political appetite for expansion of public health insurance options.

Whether the 113th Congress will pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill is highly uncertain, but the senate bill restricts family visas by eliminating the sibling visas and imposing an age cap on sponsorship of married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens. No changes in parent visas have been proposed. What our analyses demonstrate is a need for a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of late-age immigration that consider lifetime contributions to public programs and payout streams over remaining years of life. Surging health care costs and population aging, neither of which were salient policy issues when U.S. immigration policies were last overhauled in 1965, demand nothing less.

Footnotes

Australia and Canada consider age by assigning fewer points for seniors.

The Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of Immigration Statistics does publish the age distribution of legal permanent residents by sex, but not by visa categories or regions of origin.

For instance, in 2009 visas for siblings of U.S. citizens were issued to Mexican nationals whose petitions dated back to 1997 and to Filipino nationals dating back to 1986, representing waits of 12 and 23 years, respectively (U.S. Department of State (USDOS), 2011a; 2011b).

The criteria for the tabulations is specified in written communications with M. Hoefer, director, Office of Immigration Statistics, USDHS, September 21, 2010, and J. Simansky, chief, Communications Division, Office of Immigration Statistics, USDHS, November 17, 2010.

Other studies use the term “principal immigrants” to refer to initiating immigrants (Yu, 2008; Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1986), but to avoid confusion with the USDHS use of the term Principal Alien, we use the term “initiating immigrant.” For example, a sibling of a U.S. citizen sponsored under the family 4th preference would be classified as a principal alien by USDHS (because she can sponsor accompanying family dependents), but would not be considered an initiating immigrant because an earlier migrant sponsored her.

Mexican nationals accounted for 75 percent of all IRCA amnesty recipients (Rytina, 2002: 3).

Unlike the USDHS use of the term “family immigrants,” which reflects LPRs admitted as U.S. citizens’ immediate relatives or under family-sponsored preferences, we also include as “family immigrants” the accompanying family dependents of initiating immigrants (Monger, 2010: 2). For example, we characterize the accompanying family members of an employer-sponsored initiating immigrant as family immigrants, whereas USDHS classifies them under employment-based preferences admissions.

Although there exist visa backlogs for second preference family members, over the period we study these range from two to eight years for most countries and up to ten years for Mexico, with more recent petitions reaching the upper end of the spectrum (Wasem, 2010a).

Spouses of U.S. citizens may naturalize after three rather than five years as LPRs. The other naturalization requirements consist of age (18 years or older), English language proficiency, knowledge of U.S. government and history, and good moral character (Lee, 2010:1).

Eight years is the median of the total median years in LPR status during this study’s period of observation (Lee, 2010: 4).

Yu’s multiplier is inconsistent in its treatment of unmarried, adult children of U.S. citizens, variously identifying them in Phases 3 (2008: 53) and 4 (2008: 175). We adopt the latter approach and restrict admissions of all numerically capped preference relatives of citizens to Phase 4.

For an earlier period, Jasso and Rosenzweig (1990:230) estimated that less than five percent of parent sponsors were U.S.-born children who used their citizenship entitlement to sponsor parents when they reached age of majority. We contacted the Department of Homeland Security for estimates of the number of U.S.-born children who sponsor their parents and were told that direct estimates are unavailable. Furthermore, the New Immigrant Survey, which is based on the 2003 LPR admission cohort, lacks information about the age of sponsors (Jasso et al., 2006).

In the interest of parsimony, we do not elaborate the welfare reforms in detail, but some cross-state differences are noteworthy. A minority of states used their own funds to extend Medicaid benefits to new immigrants during the five-year ban, and five states created substitute income-support programs for some groups of immigrants rendered ineligible for SSI by PRWORA; however, most of these benefits were less generous than the federal program or subject to more stringent conditions relative to SSI in the pre-1996 period (Zimmerman and Tumlin, 1999).

Deeming practices vary across states, however, and few benefit agencies seek reimbursement from sponsors both because states do not face penalties for failure to pursue reimbursement and because the costs of seeking reimbursement from sponsors exceed the benefits (NILC, 2009; Ambegaokar and Blazer, 2011).

Contributor Information

Stacie Carr, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544.

Marta Tienda, Email: Tienda@princeton.edu, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, 609 258-1753 voice, 609 258--039 fax.

References

- Ambegaokar Sonal, Blazer Jon. Overcoming Barriers Immigrants Face in Accessing Health Care and Benefits. National Immigration Law Center; 2011. Retrieved at http://nilcorg/search.html. [Google Scholar]

- Angel Jacqueline L. Devolution and the Social Welfare of Elderly Immigrants: Who Will Bear the Burden? Public Administration Review. 2003;63(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Angel Ronald J, Angel Jacqueline L, Lee Geum-Yong, Markides Kyriakos S. Age at migration and family dependency among older Mexican immigrants: recent evidence from the Mexican American EPESE. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(1):59–65. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel Jacqueline L, Angel Ronald J, Markides Kyriakos S. Late-life immigration, changes in living arrangements, and headship status among older Mexican-origin individuals. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(1):389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold Fred, Cariño Benjamin V, Fawcett James T, Park Insook Han. Estimating the immigration multiplier: An analysis of recent Korean and Filipino immigration to the United States. International Migration Review. 1989;23(4):813–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Bryan C. Fact Sheet. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2007. Dec, Trends in Naturalization Rates. Retrieved January 16, 2013, from http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/natz-rates508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Bryan C. Fact Sheet. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2010. Oct, Naturalization Rates Among IRCA Immigrants: A 2009 Update. Retrieved September 25, 2012, from http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/irca-natz-fs-2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Batalova Jeanne. Senior Immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. 2012 Retrieved June 25, 2012 from http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=894.

- Binstock RH, Jean-Baptiste R. Elderly Immigrants and the Saga of Welfare Reform. Journal of Immigrant Health. 1999;1(1):31–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1022636130104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Social Security eligibility and the labor supply of older immigrants. Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 2011;64(3):485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J, Tienda Marta. The employment and wages of legalized immigrants. International Migration Review. 1993;27(4):712–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Monica. Family and personal networks in international migration: recent developments and new agendas. International Migration Review. 1989;23(3):638–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Sunha. Longitudinal changes in access to health care by immigrant status among older adults: the importance of health insurance as a mediator. The Gerontologist. 2010;51(2):156–169. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Immigration Policy in the United States: An update. CBO Publication No 4160. 2010 Dec; Retrieved December 10, 2010, from: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/119xx/doc11959/12-03-Immigration_chartbook.pdf.

- Espenshade Thomas J, Fu Haishan. An analysis of English-language proficiency among U.S. immigrants. American Sociological Review. 1997;62(2):288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Fix Michael, Passel Jeffrey S. Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform: 1994–1997. Washington, D.C: The Urban Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fix Michael, Passel Jeffrey S, Zimmerman Wendy. The Use of SSI and Other Welfare Programs by Immigrants: Testimony before the House Committee on Ways and Means. Washington, D.C: The Urban Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland Robert B, Pankaj Veena. Welfare reform and elderly legal immigrants. 1997 Retrieved on September 20, 2010 from: http://hpi.georgetown.edu/agingsociety/pdfs/welfare.pdf.

- Heinberg John D, Harris Jeffrey K, York Robert L. The process of exempt immediate relative immigration to the United States. International Migration Review. 1989;23(4):839–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Priscilla. Anchor Babies, Over-Breeders, and the Population Bomb: The Reemergence of Nativism and Population Control in Anti-Immigration Policies. Harvard Law and Policy Review. 2008;2:385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Identifying Reference, 2013.

- Jasso Guillermina, Massey Douglas S, Rosenzweig Mark R, Smith James P. The New Immigrant Survey 2003 Round 1 (NIS-2003-1) Public Release Data. 2006. Mar, Funded by NIH HD33843, NSF, USCIS, ASPE & Pew. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso Guillermina, Rosenzweig Mark R. Family reunification and the immigration multiplier: U.S. immigration law, origin-country conditions, and the reproduction of immigrants. Demography. 1986;23(3):291–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso Guillermina, Rosenzweig Mark R. Sponsors, sponsorship rates and the immigration multiplier. International Migration Review. 1989;23(4):856–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso Guillermina, Rosenzweig Mark R. The New Chosen People: Immigrants in the United States. NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Citizenship Documentation in Medicaid. Key Facts. 2007 Dec; Retrieved on July 7, 2013 from http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7533_03.pdf.

- Kennedy Edward M. The Immigration Act of 1965. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1966;367:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lee James. Annual Flow Report. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. DHS; 2010. Apr, Naturalizations in the United States: 2009. Retrieved on August 15, 2011, from http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/natz_fr_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Monger Randall. Annual Flow Report. Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2010. Apr, U.S. Legal Permanent Residents: 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2010, from http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/lpr_fr_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Monger Randall, Yankay James. Annual Flow Report. Office of Immigration Statistics, U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2011. Mar, U.S. Legal Permanent Residents: 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2011, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/lpr_fr_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nam Yunju. Welfare Reform and Older Immigrant Adults’ Medicaid and Health Insurance Coverage: Changes Caused by Chilling Effects of Welfare Reform, Protective Citizenship, or Distinct Effects of Labor Market Condition by Citizenship? Journal of Aging and Health. 2012;24(4):611–635. doi: 10.1177/0898264311428170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Immigration Law Center (NILC) Guide to Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs. 4. Los Angeles: National Immigration Law Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Immigration Law Center (NILC) Sponsored Immigrants and Benefits. 2009 Retrieved July 10, 2013 at http://nilc.org/search.html.

- Park Julie, Myers Dowell. Intergenerational mobility in the post-1965 immigration era: estimates by an immigrant generation cohort method. Demography. 2010;47(2):369–392. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles Steven J, et al. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2010. Machine-readable database. [Google Scholar]

- Rytina Nancy. IRCA Legalization Effects: Lawful Permanent Residence and Naturalization through 2001. Office of Policy and Planning, Statistics Division, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service; 2002. Retrieved August 29, 2010, from http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/irca0114int.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P. Assimilation across the Latino generations. American Economic Review. 2003;93(2):315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Smolka Gerry, Multack Megan, Figueiredo Carlos. FACT SHEET. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012. Health Costs and Coverage for 50-to-64-year-olds. [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas Aaron. Older Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute; 2009. May, Retrieved May 19, 2010, http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=727. [Google Scholar]

- Treas Judith. Old Immigrants and U.S. Welfare Reform. International Journal of Sociology & Social Policy. 1997;17(9):8–33. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division. Replacement Migration: Is it a solution to declining and aging populations? New York: United Nations; 2001. Retrieved August 8, 2011 from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/ReplMigED/migration.htm. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. The Age and Sex of Migrants: 2011 Wall Chart. New York: 2011. Population, Sales No 12.XIII.2. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Homeland Security (USDHS) Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2009. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- USDHS. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2002–2008. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; (Various, 2003–2009) For years prior to 2002, see Immigration and Naturalization Service (USINS) and its Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service (USDOJ) Immigrants Admitted To The United States, 2000 [Computer file]. ICPSR03486-v2. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service [producer]; Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2007. 2002. 2007-11-27. Also, Immigrants Admitted To The United States, [Computer files] 1980 through 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of State (USDOS), Bureau of Consular Affairs. Comprehensive lists of cut-off dates: Mexico family preference cut-off dates from FY1992-2011. 2011a Retrieved 7/30/2011 from: http://travel.state.gov/visa/bulletin/bulletin_1360.html.

- United States Department of State (USDOS), Bureau of Consular Affairs. Comprehensive lists of cut-off dates: Philippines family preference cut-off dates from FY1992-2011. 2011b Retrieved 7/30/2011 from: http://travel.state.gov/visa/bulletin/bulletin_1360.html.

- United States Department of State (USDOS), Bureau of Consular Affairs. Comprehensive lists of cut-off dates: Worldwide (non-oversubscribed countries only) family preference cut-off dates from FY1992-2011. 2011c Retrieved 7/30/2011 from: http://travel.state.gov/visa/bulletin/bulletin_1360.html.

- Van Hook Jennifer. Welfare reform’s chilling effects on noncitizens: Changes in Noncitizen Welfare Recipiency or Shifts in Citizenship Status? Social Science Quarterly. 2003;84(3):613–631. [Google Scholar]

- Wasem Ruth Ellen. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress RL32235. 2009. U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions. Retrieved January 23, 2010 via Lexis-Nexis Congressional Database. [Google Scholar]

- Wasem Ruth Ellen. U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2010a. Report RL32235. Retrieved April 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wasem Ruth Ellen. Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview and Trends. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2010b. Electronic version. Report RL33809. Retrieved July 2, 2012, from http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/key_workplace/818. [Google Scholar]

- Wasem Ruth Ellen. U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2012. Mar 13, Report RL32235. Retrieved July 2, 2012, from UNT Digital Library, http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc84039/ [Google Scholar]

- Westat, Inc. LPS Public Use File: The 1989 Legalized Population Survey (LPS1) and the 1992 Legalized Population Follow-Up Survey (LPS2) 1992 Retrieved August 29, 2010, from http://mmp.opr.princeton.ed/LPS/LPSpage.htm.

- Yu Bin. Chain Migration Explained: The power of the immigration multiplier. LFP Scholarly Publishing; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman Wendy, Tumlin Karen C. Occasional Paper # 24. Washington DC: The Urban Institute; 1999. Patchwork policies: State assistance for immigrants under welfare reform. [Google Scholar]