Abstract

Most human γδ T cells express Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs and play important roles in microbial and tumor immunity. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells are stimulated by self- and foreign prenyl pyrophosphate intermediates in isoprenoid synthesis. However, little is known about the molecular basis for this stimulation. We find that a mAb specific for butyrophilin 3 (BTN3)/CD277 immunoglobulin superfamily proteins mimics prenyl pyrophosphates. The 20.1 mAb stimulated Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones regardless of their functional phenotype or developmental origin, and selectively expanded blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. The γδ TCR mediates 20.1 mAb stimulation because IL-2 is released by β- Jurkat cells transfected with Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs. 20.1 stimulation was not due to isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) accumulation because 20.1 treatment of APC did not increase IPP levels. In addition, stimulation was not inhibited by statin treatment, which blocks IPP production. Importantly, small interfering RNA knockdown of BTN3A1 abolished stimulation by IPP that could be restored by re-expression of BTN3A1 but not by BTN3A2 or BTN3A3. Rhesus monkey and baboon APC presented HMBPP and 20.1 to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells despite amino acid differences in BTN3A1 that localize to its outer surface. This suggests that the conserved inner and/or top surfaces of BTN3A1 interact with its counterreceptor. Although no binding site exists on the BTN3A1 extracellular domains, a model of the intracellular B30.2 domain predicts a basic pocket on its binding surface. However, BTN3A1 did not preferentially bind a photoaffinity prenyl pyrophosphate. Thus, BTN3A1 is required for stimulation by prenyl pyrophosphates but does not bind the intermediates with high affinity.

Keywords: gamma delta T cell, Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells, human, butyrophilin 3, bisphosphonate, antigen presentation, prenyl pyrophosphates, isopentenyl pyrophosphate, isoprenoid metabolism, farnesyl diphosphate synthase

Introduction

Unconventional T cells, such as γδ T cells, αβ iNKT cells, and mucosal-associated invariant αβ T cells, have distinct recognition properties. Conventional CD8 and CD4 T cells use diverse αβ TCRs to recognize foreign and self-peptides presented by MHC class I and class II molecules. The peptides are derived from proteins and loaded into MHC molecules through distinct intracellular processing and loading pathways. The number of αβ T cells recognizing a particular peptide-MHC complex is generally very low such that expansion of reactive cells is required to mount effective T cell immunity. In contrast, γδ TCRs recognize nonpeptide compounds or self-cell surface molecules. Humans and mice have limited numbers of Vγ and Vδ gene segments and many γδ TCRs exhibit limited or no junctional diversity. Thus, although γδ T cells constitute a minor subpopulation among human and murine T cells, the actual precursor frequencies for a given Ag can be very high compared with the very low frequency of CD4 and CD8 αβ T cells specific for particular peptide/MHC complexes.

The major subset of human γδ T cells express Vγ2Vδ2 (also termed Vγ9Vδ2) TCRs and play important roles in immunity to microbes and tumors (1). Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expand to very high levels during many bacterial and protozoan infections, secrete inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, and kill infected cells and tumor cells. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells perform these functions by using their Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs to sense foreign and self-prenyl pyrophosphates, and by using their NK receptors to recognize ligands expressed by tumor and virally infected cells. Prenyl pyrophosphates (also termed prenyl diphosphates) are essential intermediates in isoprenoid biosynthesis required by both microbes and humans. We and others (2, 3) have identified one bacterial Ag as (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMBPP), an intermediate in the methyl-erythritol-4-phosphate isoprenoid pathway used by some bacteria and all apicomplexan parasites. Two other classes of compounds, aminobisphosphonates (4-8) and alkylamines (8-10), indirectly stimulate γδ T cells by inhibiting farnesyl diphosphate synthase in human APC causing the accumulation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP).

The molecular basis for Vγ2Vδ2 TCR recognition of prenyl pyrophosphates remains a major unanswered question in the biology of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Like αβ T cell recognition of peptides or lipids, cell-cell contact is required for prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation (11, 12). However, Ag processing is not required (11) likely explaining why presentation can be by nonprofessional APC including Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (11, 13). None of the known human Ag-presenting molecules (HLA-A, -B, -C, HLA-DR, -DQ, -DP, CD1a, b, c, d, and e, or β2M) are required (11, 14) and murine APC cannot present these compounds to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (15, 16).

Stimulation by prenyl pyrophosphates is mediated by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR as demonstrated by the transfer of prenyl pyrophosphate reactivity to β- Jurkat cells with expression of the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR (17). However, there is no evidence for direct binding of Ag by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR (18). TCR mutagenesis studies first pointed to a role for the junctional region of the Vγ2 chain (19-21) that forms a basic pocket (18, 22). We identified critical residues in all 6 CDR regions that serve to define a large binding footprint for Vγ2Vδ2 TCR recognition that is much larger than the size of HMBPP or IPP (23). Moreover, Vγ2Vδ2 TCR tetramer binding to human APC requires the presence of HMBPP and is sensitive to protease treatment of the APC surface (24). Finally, we showed that photoaffinity analogs of HMBPP can be photo-cross-linked to human cells for stimulation (16). Therefore, there is strong support for the requirement of a surface protein(s) distinct from known Ag-presenting molecules for prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation.

Recently, butyrophilin 3 (BTN3; CD277) family members have been reported to be involved in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation (25) and their structures have been determined (26). Butyrophilin (BTN) and butyrophilin-like (BTNL) proteins are immunoglobulin superfamily proteins. In humans, all six BTN genes and one BTNL gene are located in the MHC class I region of chromosome 6 and the remaining three BTNL genes on chromosome 5 (27). Most BTN/BTNL proteins are composed of extracellular IgV and IgC domains with an intracellular B30.2 domain (Supplemental Fig. 1). BTN3 family members are broadly expressed in almost all human tissues (28). One mAb specific for BTN3 stimulates Vγ2Vδ2 T cell responses whereas another blocks prenyl pyrophosphate and Daudi/RPMI8226 tumor cell stimulation (25). In this paper, we confirm and extend these findings by demonstrating specific stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells with an anti-BTN3 mAb, regardless of their functional capabilities or developmental origins. Moreover, small interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibition of only one family member, BTN3A1, abrogated prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation. BTN3A1, however, does not appear to bind prenyl pyrophosphates directly. We have also found that the ability to present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells is conserved among humans and baboons and rhesus monkeys despite amino acid differences in both the BTN3A1 extracellular domains and the B30.2 intracellular domains.

Material and Methods

Abs and flow cytometry

mAbs used included anti-Cδ (anti-TCRδ1 [5A6.E9]), anti-Vγ1 (23D12), anti-Vγ2 (7A5), anti-Vδ1 (δTCS1) (all from Pierce Abs, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), anti-Vδ2 (BB3), anti-Vδ3 (P11.5B), anti-BTN3 (1A6) (OriGene, Rockville, MD), FITC-anti-CD3 (HIT3a) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), PE-anti-Vδ2 (B6) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), unconjugated or PE-conjugated mouse IgG1 isotype control mAb (P3) (eBioscience), and unconjugated or PE-conjugated anti-BTN3/CD277 (20.1, also termed BT3.1) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Human or monkey PBMCs, human, monkey, or mouse APCs, HeLa cells before and after transfection, and tumor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan cytometer (BD Biosciences). To assess γδ TCR expression, PBMCs were stained with mAbs on ice for 30 min, washed twice, and then stained with PE-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L) Abs (Pierce Abs) on ice for 30 min, washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. To assess BTN3 expression, cells were stained with PE-20.1 or isotype control PE-P3 mAb on ice for 2 h, washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

T cell proliferation and cytokine release assays

T cell lines and clones were maintained by periodic restimulation with PHA as described previously (29). The derivation of the Vγ2Vδ2 CD8αα+ T cell clone, 12G12, and the weakly cytotoxic CD4+ γδ T cell clones, HF.2, JN.23, and JN.24, have been described previously (30-32). T cell proliferation assays were performed as described previously (14). Assays were in duplicate or triplicate in round-bottom 96-well plates using 1 × 105 T cells/well in the presence of non-fixed (mitomycin C treated) or glutaraldehyde-fixed APC at 1 × 105 cells/well for mAb, Ag, and PHA stimulation. The cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]-thymidine (2 Ci/mmol) on day 1 and harvested 16-18 h later. Mean proliferation and SEM of duplicate or triplicate cultures are shown. Stimulating compounds and inhibitors were used as indicated in the figure legends. The 20.1 and 1A6 mAbs were dialyzed prior to use in functional assays. The P3 IgG1 mAb was used as an isotype control mAb. For cytokine release, culture supernatants were harvested after 16 h and assayed for TNF-α or IFN-γ levels by DuoSet sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The primate B cell lines, GAB-LCL (derived from baboons [Papio anubis] B-lymphoblastoid cell line) and V038 AGM BLCL (derived from Sabaeus monkeys [Chlorocebus sabaeus] B-lymphoblastoid cell line) were obtained from the National Institutes of Health Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource.

In vitro expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

For in vitro expansion of blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, PBMC were prepared from the blood or leukopacs of normal donors by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation. PBMC (1 × 105) in 0.2 ml media in 96-well round bottom wells were pulsed with the compounds for 2-6 h, washed twice, or cultured continuously with the compounds. IL-2 was added to 1 nM on day 3. The cells were harvested on day 9, stained with FITC-anti-CD3 (HIT3a) or various γδ TCR-specific mAbs followed by PE-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L) Abs, and analyzed using flow cytometry. Blood was drawn from healthy adult donors who were enrolled with written informed consent in accordance with the requirements of the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Stimulation of the DBS43 Vγ2Vδ2 TCR transfectant

Derivation of the DBS43 Vγ2Vδ2 TCR transfectant has been described previously (17). Stimulation of TCR transfectants for IL-2 release was performed as previously described in the presence of 1 × 105 glutaraldehyde-fixed Va2 cells and 10 ng/ml PMA (8, 17, 33). For IL-2 assays, the supernatants were thawed and used at a 1:8 dilution to stimulate the proliferation of the IL-2-dependent cell line HT-2.

Measurement of intracellular IPP levels

MCF-7 breast cancer cells were treated with zoledronate or the 20.1 mAb for 16 h, harvested, washed twice with PBS, counted, and spun down. Cell extracts were prepared as described previously (34). Levels of IPP and triphosphoric acid 1-adenosin-5′-yl ester 3-(3-methylbut-3-enyl) ester (ApppI) were determined by separation of metabolites on high-performance ion-pairing reverse phase liquid chromatography using a Gemini C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with N,N-dimethylhexylamine formate as the ion pairing agent and analysis by negative ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry as described previously (34).

Photoaffinity Ag labeling of BTN3 proteins and Western blotting

To assess dimer formation by recombinant BTN3A1, the extracellular domain of human BTN3A1, residues A29 to R247, was expressed in Escherichia coli as inclusion bodies, solubilized in 6 M guanidine, and refolded in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) containing 1 M arginine, 0.25 mM reduced glutathione, and 0.25 mM oxidized glutathione. The refolded protein was concentrated using DE52 anion-exchange resin, isolated by Q Sepharose HP anion-exchange column chromatography, followed by size separation by Superdex 200 gel filtration. Molecular mass standards used were bovine thyroglobulin 670 kDa, bovine gammaglobulin 158 kDa, chicken OVA 44 kDa, and vitamin B12 1.35 kDa. The major peak fractions were combined and had a molecular mass of 25 kDa on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions whereas the calculated molecular mass is 23.5 kDa.

Purified full-length recombinant BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 proteins were purchased from OriGene, dialyzed against PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.5 μg in 50 μl buffer added per round bottom well of a 96-well plate. OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a control protein. Recombinant protein molecular weights and protein concentrations were confirmed by Coomassie-blue staining of SDS-PAGE-separated proteins. To assess binding of the photoaffinity Ags, the biotin-p-benzophenone-C-HMBPP Ester was added to wells containing either BTN3A1, BTN3A2, or ovalbumin at final concentrations of 0, 2, or 10 μM. The plate was then placed on ice and exposed to a 350 nm UV light. After 30 min, 30 μl of 2× Laemelli buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) containing 5% 2-ME was added to each well and mixed, and the samples moved to microtubes. Samples were then boiled for 5 min, placed on ice for 5 min, briefly spun, and 20 μl loaded to a well of a Ready Gel Tris-HCI gel (10-20% linear gradient, Bio-Rad Laboratories) for separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred overnight at 30 V, 90 mA to an Immun-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The polyvinylidene difluoride membrane containing the transferred proteins was washed twice with TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) and then blocked with 1% BSA in TBS-T for 2 h. The membrane was then washed with TBS-T three times and probed with 1:50,000 diluted streptavidin-HRP (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) for 1 h. After washing with TBS-T five times, the membrane was developed using the Visualizer Western Blot Detection kit (Millipore, Temecula, CA) with Kodak BioMax Light film.

Transfection of siRNAs and cDNAs

Silencer-27 siRNAs for BTN3 and control duplexes were purchased from OriGene and resuspended in the provided duplex buffer to obtain a 20 μM stock solution. The stock solution was further diluted to 5 μM with the same buffer for transfection and co-transfection with cDNA. Expression plasmid containing BTN3A1 and BTN3A2 cDNA (True ORF Gold) were purchased from Origene. An expression plasmid containing BTN3A3 cDNA (OmicsLink) was purchased from GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD). The control vector pCMV6-XL5 was purchased from Origene. For transfections, HeLa cells were plated at 1.7 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate 1 day prior to transfection. To transfect 1 well of HeLa cells with siRNA, 4 μl of either a control siRNA or a BTN3 siRNA was added to 100 μl of Opti-MEM I medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and then briefly mixed by vortexing. To transfect with cDNA, 1 μg of either the control plasmid or a BTN3-expressing plasmid was added to 100 μl of Opti-MEM I medium and then briefly mixed by flicking. For cotransfection of siRNA and cDNA, 1 μg of cDNA was added to 100 μl of Opti-MEM I medium followed by 4 μl siRNA. After mixing, 4.5 μl Attractene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was added to the siRNA and/or cDNA preparations. They were then vortexed for 5 s, incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and added dropwise to a well of HeLa cells. After 72 h, the transfectants were trypsinized and harvested for flow cytometric analyses or use in proliferation assays.

BTN3 sequence alignments and comparisons

BTN3A1 sequences from human (Homo sapiens), bonobo (Pan paniscus), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii), olive baboon (P. anubis), and rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) were analyzed. Most BTN3 sequences were obtained from the PubMed DNA database or from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Web site. Because the full-length baboon BTN3A1 sequence was not available, the BTN3A1 sequence was determined by using a combination of expressed sequence tag sequences from the “Baboon Seekquence” site (http://www.baboon.washington.edu/) and genome baboon sequences from the Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX) (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/content/baboon-genome-project). The BTN3A1 sequence was determined using contig 6004 for exon 1, contig 705213 for exon 2, and contig 507608 for exons 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. For exon 3 (residues 29-144), residues 29-65 were from contig 58218, residues 64-144 were from the EST clone 5974.1.1, all from P. anubis. The DNA sequence of exon 3 from P. anubis is identical to Papio hamadryas (trace 1910189173 from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Trace Archive). Sequences were aligned using the Clustal W method in the MegAlign program (Lasergene, DNAStar). Phylogenetic trees and sequence differences were determined using the MegAlign program.

Human BTN3A1 and other structural models

BTN3 extracellular domain structures used in this study include BTN3A1 (4F80), BTN3A2 (4F8Q), BTN3A3 (4F8T), and BTN3A1 complexed with the 20.1 mAb (4F9L) (26). IgV:IgC and IgC:IgC dimer structures of BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN3A3 were kindly provided by Dr. Erin Adams. Modeling of other butyrophilin IgV domains and B30.2 domains was done at the Swiss-Model Web site (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) using standard settings. The BTN3A1 B30.2 model was based on the structure of pyrin/tripartide motif (TRIM) 20 (2wl1) and was similar to other B30.2 domains differing in backbone Cα from TRIM21 by 1.35 Å2 root mean square deviation (RMSD), from pyrin/TRIM20 by 0.68 Å2 RMSD, and from TRIM72 by 1.65 Å2 RMSD. All figures were made using PyMOL X11 Hybrid (Schrödinger, LLC). The B30.2 domains are identically scaled using a PyMOL script kindly provided by Dr. W. L. DeLano. Electrostatic surface potential was calculated with the APBS PyMOL plugin (35) with, in some cases, externally generated PQR files from the PDB2PQR website (http://nbcr-222.ucsd.edu/pdb2pqr_1.8/) (36) and are colored from red (negative potential, -10 kT) to blue (positive potential, +10 kT).

Results

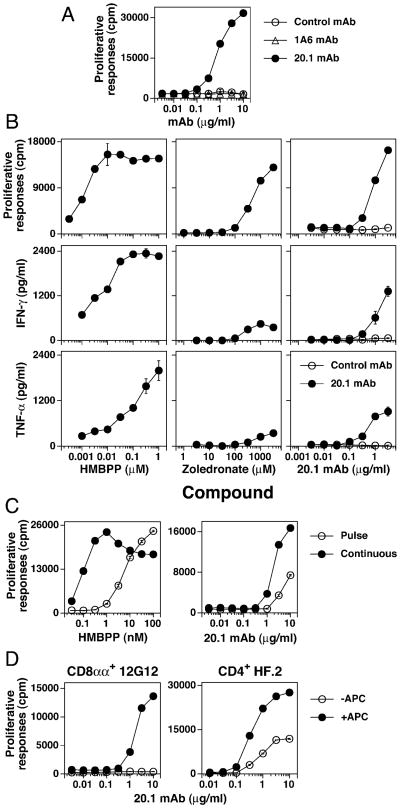

Anti-BTN3 mAb 20.1 stimulates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells to proliferate and secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α

The anti-BTN3 mAb 20.1 stimulated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells to proliferate, whereas a second BTN3 specific mAb 1A6 and a control mAb had no effect (Fig. 1A). The epitopes of the 20.l and 1A6 Abs differ because binding of 1A6 does not block 20.1 binding (data not shown). Neither mAb inhibited the 12G12 response to HMBPP (data not shown). The 20.1 mAb also stimulated IFN-γ and TNF-α release in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Cytokine responses to the 20.1 mAb were less than those seen with HMBPP but more than noted with stimulation with the aminobisphosphonate, zoledronate (Fig. 1B). The 20.1 mAb could be “pulsed” onto APC more efficiently than HMBPP with the 20.1 mAb dose response curve shifting ∼3-5 fold higher compared with the HMBPP dose response curve that shifted 54-fold higher (Fig. 1C). Similar to responses to prenyl pyrophosphates (11, 16), Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones varied in their requirement for APC to enable them to respond to the 20.1 mAb, presumably due to daughter-daughter presentation. The 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 clone required APC for responsiveness to the 20.1 mAb whereas the HF.2 clone did not (Fig. 1D). Thus, stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by the 20.1 mAb results in proliferation and cytokine production, the mAb can be “pulsed” on APC, and, like prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation, 20.1 mAb stimulation does not always require APC.

Figure 1.

Anti-BTN3 mAb, 20.1, stimulates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells to proliferate and secrete cytokines. (A) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells proliferate in response to the 20.1 but not the 1A6 mAb, although both are specific for BTN3. The 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clone was cultured with control IgG1 mAb, 1A6 mAb, or 20.1 mAb in the presence of mitomycin C-treated Va2 cells. The cells were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine after 24 h and harvested 18 h later. (B) 20.1 mAb stimulates both proliferation and cytokine production by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. 12G12 T cells were cultured continuously with the 20.1 mAb or the P3 control mAb in the presence of mitomycin C-treated Va2 cells. For HMBPP and zoledronate, mitomycin C-treated Va2 cells were pulsed with the compounds for 1 h, washed, and then cultured with the 12G12 T cell clone. Proliferative responses were measured as in (A). Supernatants were collected at 16 h for the measurement of TNF-α and IFN-γ. (C) APC pulsed with the 20.1 mAb stimulate 12G12 T cells. Mitomycin C-treated Va2 cells were pulsed for 1 h with HMBPP or the 20.1 mAb. The Va2 cells were then washed and cultured with the 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clone. Proliferative responses were measured as in (A). (D) CD8αα+ and CD4+ Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones exhibit different APC dependency for stimulation by the 20.1 mAb. The CD8 αα+ 12G12 clone and the CD4+ HF.2 clone were cultured with the 20.1 mAb in the presence or absence of mitomycin C-treated Va2 (for 12G12) or CP.EBV (for HF.2). Cell proliferations were measured as in (A). Note that the HF.2 clone proliferates in response to the 20.1 mAb in the absence of APC whereas the 12G12 clone does not.

Stimulation of T cells by the 20.1 mAb is restricted to Vγ2Vδ2 TCR-expressing cells regardless of functional phenotype or developmental origin and mediated by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR

To assess the specificity of stimulation by the 20.1 mAb, we stimulated human PBMC with either the 20.1 mAb or HMBPP for 9 d and assessed Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by flow cytometry. The 20.1 mAb stimulated expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in all donors (mean Vγ2Vδ2 T cells = 32.7 ± 14.9%), albeit at slightly lower levels than HMBPP (mean Vγ2Vδ2 T cells = 50.0 ± 18.9%) (Fig. 2A). Thus, the 20.1 mAb expanded only Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from the variety of αβ and γδ T cells present in PBMC.

Figure 2.

20.1 mAb specifically stimulates diverse Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in a Vγ2Vδ2 TCR-dependent manner. (A) 20.1 mAb specifically stimulates the expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from blood mononuclear cells. PBMC from five donors were cultured with media, HMBPP (100 nM), a control mAb (10 μg/ml), or the 20.1 mAb (10 μg/ml). On day 3, IL-2 was added to 1 nM. After 9 d, cells were stained with the indicated mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Specific stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones by the 20.1 mAb. CD8αα+/CD4- CD8- (solid bars) and CD4+ (open bars) T cell clones expressing different V genes were stimulated with the 20.1 mAb (1 μg/ml) or PHA-P (1:1000) with Va2 APC and [3H]-thymidine incorporation measured at day 2. Stimulation index was calculated as the ratio between the 20.1 and control mAb response. PHA stimulation indices were >2.5 for all clones and averaged 12.6-fold. (C) 20.1 mAb stimulation is mediated by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR. The DBS43 Vγ2Vδ2 TCR transfectant and the parent β− J.RT3-T3.5 cell line line were incubated with mitomycin C-treated Va2 APC and either the 20.1 mAb or HMBPP for 24 h. The supernatants were then harvested and used to stimulate the IL-2-dependent proliferation of HT-2 T cells.

BTN3 family members are Ig superfamily proteins that are similar to ligands for costimulatory and inhibitory receptors. If BTN3 molecules were playing similar roles in γδ T cell stimulation, Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones with different functional capabilities and surface phenotypes or those derived from different stages in development or different anatomic locations might have different requirements for either costimulation or inhibition and, thus, might have different responses to the 20.1 mAb. We compared cytotoxic Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones that were CD8αα positive or CD4 and CD8 negative (Fig. 2B, 12G12 and HD.108, solid bars) with non-cytolytic clones expressing CD4 (Fig. 2B, HF.2, JN.23, JN.24, open bars) (30), or with clones from cord blood (Fig. 2B, CB.32.26, solid bar) (29) or fetal liver (Fig. 2B, AC.8, open bar) (30). Despite these differences, all clones expressing Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs proliferated when cultured with the 20.1 mAb (Fig. 2B) suggesting that BTN3 does not stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells through mechanism involving alterations in costimulation or inhibition.

To further assess the specificity of 20.1 mAb stimulation, human γδ and αβ T cell clones expressing a variety of V gene pairs (29, 30, 32, 37) were cultured with the 20.1 mAb. Only γδ T cells expressing Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs were stimulated (Fig. 2B). Clones expressing Vγ2 paired with Vδ1 did not respond, including one clone, JR.2.28 (37), that uses the Jγ1.2 gene segment normally used by Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs. Clones expressing Vγ1Vδ2 TCR also did not respond nor did clones expressing Vγ1Vδ1 or αβ TCRs. Note that γδ clones showed identical 20.1 mAb staining whether they expressed Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs or not, making it unlikely that the 20.1 mAb cross-reacts with the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR (data not shown).

To determine whether the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR mediates 20.1 mAb stimulation, we incubated a Vγ2Vδ2 TCR Jurkat transfectant with the 20.1 mAb in the presence of Va2 APC. The 20.1 mAb stimulated IL-2 release by the DBS43 Vγ2Vδ2 TCR transfectant in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2C, right panel) although at somewhat lower levels than HMBPP (Fig. 2C, left panel). Thus, transfer of the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR to β- Jurkat thymoma cells (from the αβ T cell lineage) conferred the ability to respond to the 20.1 mAb.

Stimulation by the 20.1 mAb is not due to the accumulation of IPP in APC

Aminobisphosphonates and alkylamines indirectly stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by blocking farnesyl diphosphate synthase causing IPP and its ATP derivative (ApppI) to accumulate and stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (5, 7, 10). Because this process is dependent on the flow of metabolites down the mevalonate pathway, inhibiting the upstream 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase enzyme with a statin blocks stimulation by these compounds even at low statin concentrations (8, 16, 38). To determine whether the 20.1 mAb uses a similar indirect mechanism, we determined the sensitivity of 20.1 mAb stimulation to statin treatment (Fig. 3A). The 20.1 mAb response required high mevastatin concentrations for inhibition (IC50% = 45 μM) that were identical to those needed to block the HMBPP response (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the response to the aminobisphosphonate, risedronate, was highly sensitive to statin inhibition with complete inhibition even at the lowest mevastatin concentration (IC50% = <0.1 μM) (Fig. 3A). Similar findings were noted with the less potent statin pravastatin. Confirming the statin inhibition results, IPP and ApppI levels remained below detectable levels after 20.1 treatment of MCF-7 cells (<1 pmol/1 × 106 cells) (Fig. 3B) whereas zoledronate treatment increased IPP to 912 pmol/1 × 106 cells and ApppI to 44 pmol/1 × 106 cells. Thus, the 20.1 mAb does not stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells through IPP or ApppI accumulation.

Figure 3.

Stimulation by the 20.1 mAb is not due to accumulation of IPP in APC. (A) Stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by the 20.1 mAb or by HMBPP is relatively resistant to statin inhibition. Statin inhibition of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell proliferation to HMBPP (0.1 μM), risedronate (1 mM), or the 20.1 mAb (3.16 μg/ml) was tested using mitomycin C-treated Va2 cells that were pulsed with HMBPP or risedronate in the presence of either mevastatin or pravastatin for 1 h, washed, and cultured with 12G12 T cells in the presence of the statins. The 20.1 mAb was continuously present in the culture. After 24 h, the cells were pulsed with [3H]-thymidine and harvested 18 h later. Results are shown as the percentage of the control proliferative response without the statins. (B) 20.1 mAb treatment does not increase IPP or ApppI levels. MCF-7 cells were untreated or incubated for 24 h with a control mAb (5 μg/ml), the 20.1 mAb (5 μg/ml), or zoledronate (25 μM). Cells were then harvested, washed, and lysed with acetonitrile for determination of IPP and ApppI levels by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

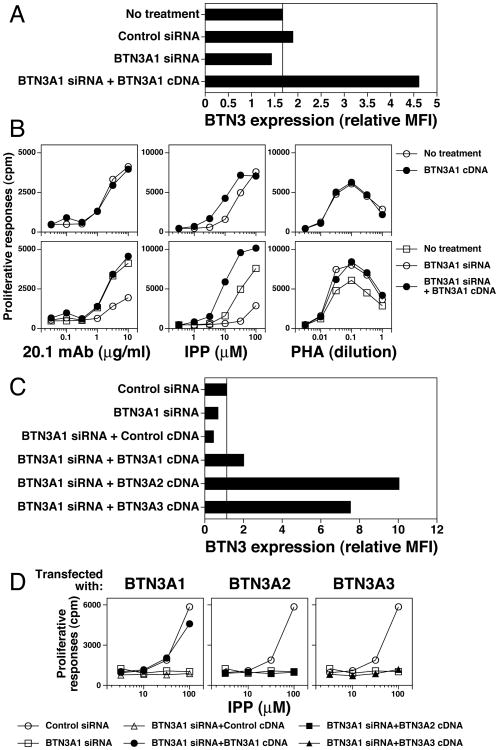

siRNA inhibition of BTN3A1 abolishes stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by IPP

The BTN3 family is composed of three members, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN3A3, that have highly similar IgV domains (99%) but less conserved IgC domains (90-91%) and different intracellular tails (Supplemental Fig. 1). The 20.1 mAb binds all three members (26). To assess the role of the different BTN3 family members in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation, siRNAs specific for each of the BTN3 proteins were used to decrease their expression. The HeLa cell line was used for these experiments because its low BTN3 expression allowed near total inhibition of BTN3 expression. Cells were transfected with siRNA and then tested for BTN3 surface expression and for their ability to function as APCs for IPP. After siRNA treatment, HeLa cells downregulated their low expression of BTN3 proteins to near background levels (Fig. 4A). HeLa cells treated with siRNAs specific for BTN3A1 lost their ability to efficiently support IPP responses (Fig. 4B, upper center panel). In contrast, HeLa cells treated with siRNA specific for either BTN3A2 or BTN3A3 still presented IPP (Fig. 4B, middle and lower center panels). Each of the siRNAs partially inhibited the 20.1 mAb response (Fig. 4B, left panels). None of the siRNAs inhibited responses to the PHA mitogen (Fig. 4B, right panels). These results suggest that all three family members can support 20.1 mAb responses but only BTN3A1 supports IPP responses.

Figure 4.

siRNA inhibition of BTN3A1 in APC abolishes IPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) siRNA inhibition of BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN3A3 expression. HeLa cells were transfected with either control siRNA or with siRNAs specific for each of the members of the BTN3 family. After 72 h, transfected HeLa cells were stained with the 20.1 mAb and BTN3 surface expression determined by flow cytometry. (B) siRNA inhibition of BTN3A1 greatly reduces IPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. siRNA transfected HeLa cells were used as APC for 20.1 mAb, IPP, and PHA stimulation of the 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clone. Note that for each of the siRNA shown, there was at least one additional siRNA with a similar effect (i.e. oligo A for BTN3A1, oligo C for BTN3A2, and oligo A and C for BTN3A3).

Re-expression of BTN3A1 but not BTN3A2 or BTN3A3 in siRNA-treated HeLa cells restores presentation of IPP to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

To ensure that the loss of BTN3A1 on APC was responsible for their inability to present IPP rather than off-target effects or toxicity from the siRNA treatment, we restored BTN3A1 expression in HeLa cells after siRNA knockdown and assessed the ability of the cells to present IPP and to support 20.1 mAb responses. Consistent with our earlier experiments, BTN3A1 siRNA treatment decreased 20.1 mAb staining (Fig. 5A) and greatly decreased IPP presentation (Fig. 5B, middle lower panel, open circles). siRNA for BTN3A1 also partially decreased 20.1 mAb responses (Fig. 5B, left lower panel). Cotransfection of the BTN3A1 siRNA with BTN3A1 cDNA in an expression plasmid restored BTN3 expression on HeLa to levels higher than normal (Fig. 5A). Importantly, expression of BTN3A1 in siRNA-treated cells restored their ability to present IPP such that they were even more efficient than untreated cells (compare closed circles with open squares in Fig. 5B, middle lower panel). Similarly, expression of BTN3A1 in siRNA-treated cells restored their ability to support 20.1 mAb responses (Fig. 5B, left lower panel). All treated cells were able to support control PHA mitogen responses (Fig. 5B, right panels). Thus, the effect of siRNA to BTN3A1 is due to the downregulation of the BTN3A1 protein.

Figure 5.

Re-expression of BTN3A1 but not BTN3A2 or BTN3A3 in siRNA-treated APC restores IPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) Transfection of BTN3A1 cDNA restores siRNA-inhibited BTN3 expression on HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated BTN3 siRNA or cotransfected with BTN3 siRNA and cDNA. After 72 h, the transfectants were stained with either PE-conjugated isotype control mAb or the 20.1 mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was calculated as 20.1 mAb MFI minus isotype control mAb MFI. (B) Transfection of BTN3A1 cDNA in APC restores BTN3 siRNA-inhibited IPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA or co-transfected with the indicated siRNA and cDNA. After 72 h, the transfectants were harvested, washed, and treated for 1 h with mitomycin C. The transfectants were then cultured with half-log dilutions of the 20.1 mAb, IPP, or PHA followed by addition of 12G12 T cells. Proliferative responses were assessed as in Fig. 1A. (C) Transfection of BTN3A1, BTN3A2, or BTN3A3 cDNA restores BTN3 expression on HeLa cells treated with BTN3 siRNA. HeLa cells were transfected with BTN3A1 siRNA oligo B or cotransfected with BTN3A1 siRNA oligo B and the indicated BTN3 cDNA as detailed in (A). After 72 h, BTN3 expression was assessed by flow cytometry. (D) Transfection of BTN3A1 but not BTN3A2 or BTN3A3 cDNA in BTN3 siRNA-treated APC restores IPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. HeLa cells were transfected with BTN3A1 siRNA oligo B or co-transfected with BTN3A1 siRNA oligo B and the indicated BTN3 cDNA. After 72 h, the transfectants were harvested, washed, and treated for 1 h with mitomycin C. The transfectants were then cultured with half-log diluted IPP followed by addition of 12G12 T cells. Proliferative responses were assessed as in Fig. 1A.

To further assess the specificity of presentation of prenyl pyrophosphates by BTN3A1, we compared the ability of the different BTN3 family members to restore presentation by HeLa cells treated with siRNA. Despite restoring BTN3 expression in siRNA-treated cells to levels higher than those found on the untreated cells (Fig. 5C), HeLa cells expressing either BTN3A2 or BTN3A3 were unable to present IPP (Fig. 5D, middle and right panels) whereas HeLa cells expressing BTN3A1 presented IPP similar to cells treated with a control siRNA (Fig. 5D, left panel). Thus, despite strong similarities in the extracellular domains between BTN3A1, BTN3A2, and BTN3A3 (Supplemental Fig. 1), only BTN3A1 is required for the presentation of prenyl pyrophosphates.

BTN3A1 does not bind prenyl pyrophosphates with high affinity

The requirement for BTN3A1 surface expression for the presentation of prenyl pyrophosphates suggests that it could function as a presenting molecule similar to MHC class I and II or CD1 molecules. Proteins binding prenyl pyrophosphates and other phosphorylated compounds commonly employ two mechanisms to accommodate their negative charges. In some cases, positively-charged binding pockets are formed by the presence of lysine and arginine basic amino acids with additional polar residues (39). These can form ionic and hydrogen bonds to the pyrophosphate moiety. A second mechanism used by many enzymes in isoprenoid synthesis is the presence of precisely positioned acidic residues (the DDXXD motif) that coordinate the binding of three positively charged divalent magnesium cations that then form ionic bonds to the negative charges on the pyrophosphate moiety (40, 41). Hydrophobic pockets accommodate the isoprenoid acyl tails (41). To determine whether there were potential binding pockets in BTN3A1, the electrostatic surface potential of the molecule was calculated. Only a shallow, mildly basic area was noted on the extracellular portion of BTN3A1 (Fig. 6A) whereas a deep, highly basic pocket was predicted on a structural model of the intracellular B30.2 domain. Although similar pockets were predicted for the B30.2 domains of BTN3A3, BTNL3, BTNL8, and BTNL9 (but not BTN1A1, BTN2A1, or BTN2A2, Supplemental Fig. 2A), this pocket is not present on B30.2 crystal structures of TRIM21 (Fig. 6B), TRIM72, SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein-3, pyrin, or Gustavus (Supplemental Fig. 2A). The extracellular domains of BTN3 molecules form homodimers in crystals (26). To determine if the extracellular domains of BTN3A1 also form homodimers in solution, recombinant BTN3A1 was sized by size-exclusion chromatography. Almost all of the BTN3A1 was present as homodimers suggesting proper folding and dimerization (Fig. 6C). To determine if recombinant BTN3A1 (with its B30.2 tail) or BTN3A2 (without a B30.2 tail) preferentially binds prenyl pyrophosphates, we reacted the BTN3 proteins or control OVA protein with a biotinylated photoaffinity prenyl pyrophosphate Ag (synthesis detailed in Supplemental Fig. 2B). Although this compound stimulates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells with an EC50% of 1.0 nM in continuous culture and 39.9 nM with pulsing and exposure to UV light (data not shown), there was no evidence for preferential labeling of either BTN3A1 or BTN3A2 when compared with OVA (Fig. 6D). Thus, despite the presence of potential binding sites, there was no preferential prenyl pyrophosphate binding to the BTN3A1 protein when compared with BTN3A2 or OVA.

Figure 6.

BTN3A1 dimers have a basic pocket on the binding face of the intracellular B30.2 domain but do not bind with high affinity to a photoaffinity prenyl pyrophosphate. (A) The surface potential of the extracellular BTN3A1 dimer. The surface potential was calculated in PyMOL using the APBS plugin and is colored from red (-10 kT) to blue (+10 kT). (B) Basic pocket on the binding face of the BTN3A1 B30.2 domain. Left panels, Model of BTN3A1 B30.2 domain (gray color) superimposed on the crystal structure of the TRIM21 B30.2 domain (blue color) with variable regions 1-4 labeled. Middle, right panels, Surface potentials of the B30.2 domains of BTN3A1 and TRIM21 from top (upper panels) and side views (bottom panels) were calculated as in A. The IgG Fc domain binds to the top of TRIM21 via the v1-v4 regions. (C) The extracellular domain of recombinant BTN3A1 predominantly exists as a dimer. The extracellular domain of BTN3A1 was expressed in E. coli, refolded, and size separated by Superdex 200 gel filtration. The position of the BTN3A1 dimer and monomer are indicated. (D) Biotin-BZ-C-C5-pyrophosphate (diphosphate) does not preferentially label BTN3A1 or BTN3A2. Recombinant BTN3A1, recombinant BTN3A2, or ovalbumin (OVA) were incubated with a biotin-benzophenone-C-C5-pyrophosphate label (structure is shown) and exposed to 350 nm UV light for 90 min on ice. Two hundred fifty nanograms of each protein were then separated on a 10-20% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were blotted and biotinylated proteins visualized with streptavidin-HRP.

Baboon and rhesus monkey APCs present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

Responsiveness to prenyl pyrophosphates is conserved within the primate lineage. Both Old World and New World monkeys have Vγ2Vδ2 T cells that recognized IPP and other prenyl pyrophosphates (33, 42-44) and that can expand during bacterial infections (45, 46). However, xenogeneic presentation of prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells has not been studied extensively. Therefore, we tested APCs from different primate species for their ability to present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clones and for BTN3 cross-reactivty with the 20.1 mAb. Both baboon and rhesus monkey cells reacted with the 20.1 mAb (Fig. 7A, B). Baboon B cell APC stimulated the CD8αα+ 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clone after culture with HMBPP or risedronate (Fig. 7C). Unexpectedly, despite apparent mAb reactivity, baboon B cells support very minimal 20.1 mAb responses (Fig. 7C) although baboon and other primate B cells did support PHA responses by 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 7C). The CD4+ HF.2 Vγ2Vδ2 T cell clone gave similar results (Fig. 7D, E). In this case, baboon B cells augmented the self-presentation of HMBPP to HF.2 with identical dose response curves to human B cells (EC50% of 0.20 nM for baboon versus 0.13 nM for human APC). However, baboon B cells supported only weak 20.1 mAb responses (Fig. 7C). Rhesus monkey PBMC also presented HMBPP as efficiently as human PBMC (EC50% of 1.3 nM for rhesus versus 1.0 nM for human APC), but again 20.1 mAb stimulation was inefficient requiring 20-fold higher concentrations to stimulate half maximal responses (EC50% of 0.60 μg/ml for rhesus PBMC versus 0.03 μg/ml for human PBMC). Thus, the ability to present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells is highly conserved between humans and baboons/rhesus monkeys but less conserved for stimulation by the 20.1 mAb.

Figure 7.

BTN3-expressing baboon and rhesus monkey APC present prenyl pyrophosphates and the 20.1 mAb to stimulate human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) Baboon herpesvirus-transformed B cells express BTN3. Baboon B, human B, and mouse T cells were stained with PE-conjugated-isotype-control or PE-20.1 mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Rhesus monkey monocytes and lymphocytes express BTN3. Rhesus and human PBMC were isolated and stained as in (A). The histogram plots of cells gated for monocytes and lymphocytes are shown. (C) Baboon B cells can present nonpeptide Ags to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Human CP.EBV B cells and two monkey B cell lines were treated with mitomycin C for 1 h and then either pulsed for 1 h with HMBPP or risedronate, or continuously cultured with the 20.1 mAb or PHA-P. Human 12G12 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were then added and proliferative responses assessed as in Fig. 1A. (D) Baboon B cells present prenyl pyrophosphates and the 20.1 mAb to human HF.2 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Human HF.2 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were cultured with HMBPP, the 20.1 mAb, or PHA-P in the presence or absence of mitomycin-treated CP.EBV human B cells or GAB-LCL baboon B cells and proliferative responses assessed as in Fig. 1A. (E) Rhesus and human PBMC present prenyl pyrophosphates and the 20.1 mAb to human HF.2 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (as in D).

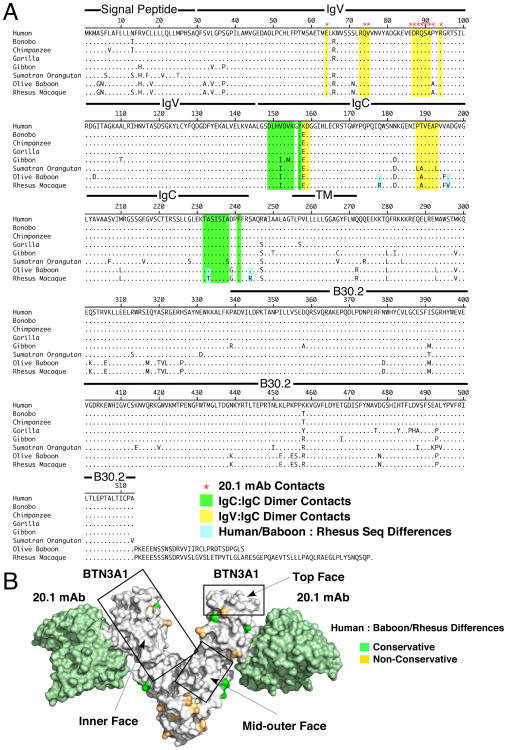

The BTN3A1 protein is highly conserved across evolutionary time in the primate lineage (Fig. 8A, Supplemental Fig. 3A, B) but not present in other mammalian species. Human BTN3A1 has 92.4% sequence identity with baboon BTN3A1 and 91.6% identity with rhesus monkey BTN3A1 (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The IgV domains are the most highly conserved regions (93.9% for baboon and 94.8% for rhesus) followed by the B30.2 (94.3% for baboon and 94.3% for rhesus) and IgC domains (92.8% for baboon and 89.2% for rhesus) (Supplemental Fig. 3A, B). Regions of dimer contacts (yellow and green shaded sequences) are also highly conserved (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the 20.1 mAb binding site is either completely conserved (five primates) or has a single proline to alanine difference at residue 92 in baboons and rhesus monkey (Fig. 8A). Signal peptide sequences and the intracellular regions before the B30.2 domains are the least conserved.

Figure 8.

Amino acid differences between human and monkey BTN3A1 localize to the outer face of the BTN3A1 dimer. (A) Amino acid alignment for primate BTN3A1. The amino acid sequences for various primate BTN3A1 proteins were aligned using the Clustal W method. Locations of IgV, IgC, and B30.2 structural domains are indicated. Sequences shaded yellow highlight the IgV to IgC contacts whereas sequences shaded green highlight the IgC to IgC contacts. Red asterisks indicate residues making up the 20.1 mAb epitope. (B) Conservative and nonconservative amino acid differences between humans and baboons/rhesus monkeys localize to the outer face of the BTN3A1 dimer. The BTN3A1 extracellular dimer in complex with the 20.1 mAb is shown with conservative (shaded green) and nonconservative (shaded orange) differences located on the structure. Conserved areas on the top, inner face, and mid-outer face are boxed.

Given that baboon and rhesus monkey APC can present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, the sequence differences between human and monkey BTN3A1 do not disrupt presentation. Baboon and rhesus monkey BTN3A1 are highly homologous (96.3% sequence identity) with only three amino acid differences in their extracellular domains (Fig. 8A). When the amino acid differences between humans and monkeys are mapped onto the structure of the extracellular domains of BTN3A1, the differences are concentrated on the outer face of the molecule opposite from the IgC:IgC dimer contact region leaving a completely conserved top and inner face that partially wraps around the middle of the molecule (boxed regions in Fig. 8B and shown in more detail in Supplemental Fig. 4A, B). When differences between human and baboon or human and gorilla B30.2 domains are located on a model of the BTN3A1 B30.2 domain, they clustered in regions away from the binding face (where the basic pocket is located) (Supplemental Fig. 4C). Thus, the inner, top, and outer middle segments of the extracellular IgV/IgC domains of the BTN3A1 protein as well as the binding face of its B30.2 domain are highly conserved in primates.

Discussion

Stimulation by prenyl pyrophosphates is a unique feature of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells that allows them to detect microbes producing isoprenoid metabolites such as HMBPP as well as human cells with alterations in their isoprenoid metabolism resulting in elevated levels of IPP. Although stimulation is mediated by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR (17) and dependent on residues in all CDRs of the Vγ2 and Vδ2 regions (19, 23), the molecular basis for this stimulation has not been determined. In this paper, we have studied the role of the BTN3 family of Ig superfamily proteins in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation. We find that BTN3A1 plays a major role in this stimulation. Binding of the 20.1 mAb to BTN3 proteins activates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, regardless of their functional phenotype or developmental origin, in an identical manner to HMBPP, IPP, and other prenyl pyrophosphates. Importantly, siRNA inhibition of the expression of one family member, BTN3A1, abrogates stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by IPP that can be restored by re-expression of BTN3A1 but not by BTN3A2 or BTN3A3. Moreover, baboon and rhesus monkey APC stimulate human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in the presence of either HMBPP or the 20.1 mAb demonstrating the conservation of BTN3 function despite their divergence ∼23 million years ago (47). All of the results point to a primary role for BTN3A1 in Vγ2Vδ2 TCR recognition of prenyl pyrophosphates.

Most previous studies on the function of BTN3 family members examined their effects on αβ T cells and APCs and did not distinguish between the different BTN3 family members. These studies pointed to BTN3 functioning as ligands binding to inhibitory receptors on αβ T cells (48, 49) or as stimulatory signaling molecules expressed by αβ T cells (50) and APC (51). Overexpression of BTN3 on tumor cells or the addition of anti-BTN3 mAbs moderately inhibits CD4 and CD8 αβ T cell responses to anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs (48, 49). Similar effects are observed with other butyrophilin (52, 53) and butyrophilin-like molecules (54-56) and likely reflect BTN/BTNL binding to an inhibitory receptor(s) expressed by T cells. BTN3 proteins may also function as signaling molecules. Thus, enhanced stimulation of CD4 αβ T cells by the addition of plate bound 20.1 anti-BTN3 mAbs to anti-CD3 mAbs suggests that ligation of BTN3 provides a costimulatory signal to T cells, especially for IFN-γ secretion (50). Ligation of BTN3 on monocytes and immature dendritic cells provides a survival signal, upregulates CD80, CD86 (B7-1 and B7-2), and MHC class II, and increases secretion of IL-8, IL-1β, and IL-12/p70 to LPS (51). Thus, markedly different functions are described for BTN3 depending on the cell type suggesting that BTN3 functions as both a ligand for counterreceptor(s) on αβ T cells and as a signaling receptor on T cells and APCs. The effects of BTN3 on αβ T cells are in general agreement with the role of most B7-related immunoglobulin family members as they commonly function as ligands for costimulatory or inhibitory receptors expressed by T cells.

In contrast to the costimulatory/inhibitory role for αβ T cells, BTN3 plays a central role in the activation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. As reported in this study and in other recent studies (25, 26), stimulation by the 20.1 mAb precisely mimics stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by prenyl pyrophosphates. Unlike most antibodies specific for CD28 or other costimulatory receptors, 20.1 mAb ligation of BTN3 stimulates full Vγ2Vδ2 T cell activation in vitro with proliferation and IFN-γ release. Moreover, although costimulation receptors vary between CD4 and CD8 αβ T cells, the 20.1 mAb stimulated both CD4+ and CD8αα+/CD4-8- Vγ2Vδ2 T cells regardless of their functional phenotype or developmental origin. Costimulatory receptors are generally shared between αβ T cells with similar functions or differentiation states. In contrast, we find that 20.1 mAb stimulates only Vγ2Vδ2 clones and not other γδ clones expressing other TCRs even though they have similar functional capabilities and were derived in the same cloning. Finally, both human β- Jurkat (this paper and Ref. 25) as well as murine 58α-β- tumor cells (25) transfected with Vγ2Vδ2 TCRs responded to the 20.1 mAb, despite the αβ T cell origins of the parent cells line and despite the fact that mice do not express BTN3 orthologs, making it unlikely that they express BTN3-specific costimulatory receptors. Also, because murine cells do not express BTN3 and show no 20.1 reactivity on flow cytometric analysis, 20.1 mAb stimulation of a murine Vγ2Vδ2 transfectant rules out a direct signaling role for BTN3 in T cells. There was also no increase in intracellular IPP or high sensitivity to statin inhibition that would suggest BTN3 signaling into APC causing isoprenoid alterations.

Although it is possible that the 20.1 mAb functions as a superagonist mAb, it would be required to be highly specific only for Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and to function in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation but not in stimulation by mitogens or anti-CD3 mAbs. In this respect it would differ from the superagonistic anti-CD28 mAb TGN1412 (57), which does not show this specificity. Although the TGN1412 anti-CD28 mAb stimulates T cells to proliferate and produce cytokines, it activates most effector CD4 αβ T cells without V-region specificity (57, 58). Thus, model 3 and model 4 (Fig. 9) are unlikely to explain BTN3A1 function in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation.

Figure 9.

Models for BTN3A1 involvement in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation. In model 1, BTN3A1 binds prenyl pyrophosphates extracellularly with or without the contribution of a second protein with direct contract of the prenyl pyrophosphate to the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR. In model 2, the BTN3A1 B30.2 domain associates with a protein that either binds prenyl pyrophosphates directly or stabilized the binding of the prenyl pyrophosphates to the B30.2 domain intracellularly causing a change in BTN3A1 conformation or distribution leading to Vγ2Vδ2 T cell stimulation. In model 3, BTN3A1 acts as a ligand binding to a costimulatory or inhibitory receptor on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. In model 4, BTN3A1 functions as an APC signaling receptor.

If BTN3A1 does not stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by binding to costimulatory receptors or blocking inhibitory receptors or by signaling into APC, how might it function in prenyl pyrophosphate recognition? One possibility is that it could function like an MHC class I/II or CD1 presenting molecule. In this case, BTN3A1 would bind to prenyl pyrophosphates for recognition by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR and binding would be extracellular (model 1; Fig. 9). This model appears less likely because there is no evidence for preferential BTN3A1 binding to a photoaffinity prenyl analogue (Fig. 6D). Nor does BTN3A1 have an obvious binding pocket for prenyl pyrophosphates in its extracellular structure. Moreover, all three members serve to stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells when bound to the 20.1 mAb and are highly homologous in their extracellular domains, yet only BTN3A1 is required for prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation.

Although there is no evidence for direct prenyl pyrophosphate binding to BTN3A1, the ability of monkey APC to present prenyl pyrophosphates to human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells suggests that there may be conserved binding regions in the BTN3A1 extracellular domain. Consistent with this hypothesis, amino acid differences between monkey and human BTN3A1 all localize to the outer face of the BTN3A1 dimer (where the 20.1 binding site is located (26)), with the inner, outer middle, and top faces totally conserved. We speculate that these areas are potential binding regions for the human Vγ2Vδ2 TCR or for other proteins involved in prenyl pyrophosphate recognition. The ability of another anti-BTN3 antibody, 103.2, to specifically block prenyl pyrophosphate responses is consistent with direct binding to BTN3 for activation (25, 26).

Primate APC showed similar efficiency as human APC in HMBPP stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells but only supported weak 20.1 mAb responses (Fig. 7C-E), despite similar levels of BTN3 expression by 20.1 mAb staining (Fig. 7A, 7B). This result may reflect differences in the amino acid sequences of primate and human BTN3 family members. These differences could decrease the ability of BTN3 family members to stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells but not affect 20.1 mAb binding. In humans, all BTN3 family members bind the 20.1 mAb because they have complete homology in the 20.1 mAb epitope and 99-100% overall sequence homology in their IgV domains (26). Re-expression of any one of the BTN3 members restores 20.1 mAb stimulation although the relative effectiveness of each member has not been assessed quantitatively (25). In contrast, rhesus monkey and baboon BTN3A1 have a major nonconservative difference in the 20.1 epitope (proline to alanine at residue 92) that may decrease or abolish 20.1 mAb binding. The other monkey BTN3 family members do have the 20.1 mAb epitope but show additional differences such that the IgV region of rhesus monkey BTN3A1 shares only 93.7% and 94.6% homology to the IgV regions of monkey BTN3A2 and BTN3A3. These differences include a nonconservative difference (threonine to alanine at residue 105) on the rim of the inner face of the IgV region of rhesus monkey BTN3A2 which is completely conserved between rhesus monkey and baboon BTN3A1 and human BTN3A1. Thus, because of these differences, monkey BTN3A2 and BTN3A3 may stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells less efficiently upon binding to the 20.1 mAb accounting for the weaker 20.1 mAb responses observed. Also, because the expression of each of the BTN3 family members may differ from cell type to cell type, if the BTN3 family members differ in their ability to stimulate after 20.1 mAb binding, then these differences in expression could also contribute to the poor 20.1 mAb responses.

If the extracellular domain of BTN3A1 does not bind prenyl pyrophosphates, how are these compounds sensed by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells? Harly et al. (25) demonstrated that the intracellular B30.2 domain of BTN3A1 is required for prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation. Truncation of the BTN3A1 intracellular B30.2 domain abolishes its ability to mediate prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation whereas swapping the BTN3A3 intracellular tail with the BTN3A1 tail allows the chimeric BTN3A3 (extracellular domain)-BTN3A1 (tail) protein to restore prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation to cells lacking BTN3A1 (25). Thus, the B30.2 domain is required for BTN3A1 function and may be involved in the sensing of prenyl pyrophosphates.

B30.2 domains are present in most butyrophilin proteins and are homologs of the evolutionarily older PRY-SPRY domains (59). In humans, B30.2/PRY-SPRY domains have been identified in 97 proteins belonging to 15 protein families (60). When their binding partners have been identified, B30.2/PRY-SPRY domains are found to mediate protein interactions (60). Several proteins containing B30.2/PRY-SPRY domains are involved in innate immunity (27, 59, 61). For example, the 68 TRIM family proteins (62), which have E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, include TRIM21 (an intracellular protein that binds to Ig Fc regions (63) as well as to the cytosolic DDX41 dsDNA sensor (64)), TRIM5α (65) (an HIV-1 capsid binding protein that blocks HIV-1 replication in monkeys), and TRIM20/pyrin (66) (a protein binding to caspase 1 blocking IL-1β maturation that is mutated in familial Mediterranean fever), all contain PRY-SPRY domains and are involved in innate immunity.

B30.2/PRY-SPRY domains have a two-layered β-sandwich structure with six hypervariable loops that are similar to Ig CDR regions (63). The variable loops of B30.2 domains form the binding interface for their interacting proteins (63, 65, 67, 68). The v1-v4 variable regions that dictate viral restriction specificity in TRIM5α (65, 69) center over these hypervariable loops. We have identified the variable regions in BTN3A1 by sequence alignment with other B30.2/PRY-SPRY domains and have modeled the BTN3A1 B30.2 domain structure (Fig. 6B). When we compare the B30.2 sequence of rhesus BTN3A1 and human BTN3A1, the v1-v4 regions are highly conserved (1 difference in v1, 3 differences in v3). In contrast, the B30.2 sequence of human BTN3A3 has 4 amino acid differences in v1, 2 amino acid differences in v2, and 2 amino acid differences in v3, along with other framework differences. The strong conservation of variable region sequences of the B30.2 domain of BTN3A1 suggests a conserved binding partner between humans and monkeys.

The structural model of the B30.2 domain from BTN3A1 predicts a prominent basic pocket on the binding face of the domain. This basic region is not found in any of the other PRY-SPRY domains whose structures have been determined (Fig. 6B and Supplemental Fig. 2) but is predicted to be present to varying degrees in five of the eight human BTN/BTNL proteins with B30.2 domains (Supplemental Fig. 2). The binding sites of many phosphate-binding proteins contain basic amino acids to allow the formation of ionic bonds to the negative charges on the phosphate moieties. Yet, there was no preferential binding of the photoaffinity prenyl pyrophosphate probe to the full length BTN3A1 protein (Fig. 6D). Although it is possible that the B30.2 domain was not properly folded, an alternative possibility is that B30.2 domain binding to prenyl pyrophosphates is of low affinity. This would be similar to the low affinity binding of various drugs, such as sulfamethoxazole (70), lidocaine (71), or carbamazepine (72) to MHC class I and class II molecules that is still sufficient to allow recognition by human CD4 and CD8 αβ T cells that mediate allergic drug responses (73, 74). In this model (model 2; Fig. 9), a second protein binds to the B30.2 domain stabilizing the interaction between the B30.2 domain and prenyl pyrophosphates. Alternatively, the B30.2 domain may not contact prenyl pyrophosphates at all. Instead, the B30.2 domain binds to a second protein that associates with it after binding to a prenyl pyrophosphate. Consistent with the involvement of a second human protein, transfection of BTN3A1 into murine APCs did not allow them to function as APC for Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (25).

If binding to prenyl pyrophosphates occurs within cells (model 2; Fig. 9), how is this binding detected by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells? The ability of the 20.1 mAb to precisely mimic stimulation by prenyl pyrophosphates through binding to any BTN3 family member suggests that increases in the density of BTN3 or alterations in the conformation of the extracellular domains of BTN3 mediate this stimulation. The topology of binding of the 20.1 mAb allows BTN3A1 to multimerize (26) which is consistent with the decreased lateral motility of BTN3 after 20.1 treatment (25). 20.1 mAb binding to the BTN3A1 dimer also induces a ∼19 Å rotational shift (26). A similar conformational shift occurs in integrin molecules through “inside-out” signaling when cells are activated which greatly increases their affinity for their ligands (75). We hypothesize that BTN3A1 molecules detect prenyl pyrophosphates intracellularly through its B30.2 domain either by directly binding to them with a second protein or by associating with a protein that can bind them (model 2; Fig. 9). This intracellular binding to BTN3A1, induces an extracellular conformational change or multimerization allowing binding by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR or by an associated T cell protein. Binding of the 20.1 mAb mimics stimulation by HMBPP and other phosphoantigens by inducing a similar conformational change or multimerization. The requirement for a second protein would explain why expression of BTN3A1 in murine APC is not sufficient for prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (25).

In summary, BTN3A1 plays a critical role in prenyl pyrophosphate and tumor cell stimulation of primate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. However, rather than functioning as a costimulatory ligand or as a classical presenting molecule binding prenyl pyrophosphates with its ectodomains, it appears to function as a sensor for the intracellular levels of IPP and HMBPP. We speculate that this sensing requires an additional protein that binds to the B30.2 domain in the presence of prenyl pyrophosphates or other phosphoantigen to effect a conformational shift or multimerization of BTN3A1 on the cell surface. Extracellular HMBPP or IPP would then be recognized due to their rapid internalization by fluid-phase endocytosis. This is the mechanism by which aminobisphosphonates are internalized (76). Also, like aminobisphosphonates (8), this uptake would not be blocked by APC fixation (11). The requirement for BTN3A1 is reminiscent of the requirement for Skint-1 molecules for the development of murine dendritic epidermal Vγ5Vδ1 T cells (77). Skint-1 molecules have similar IgV and IgC extracellular domains to BTN3 with 43% homology to the BTN3A1 IgV domain. Moreover, like BTN3A1, the Skint-1 extracellular domains by themselves are not sufficient for function but instead, the full-length sequence is required including the cytoplasmic tail with its three transmembrane domains (78). Perhaps, this requirement reflects the association of Skint-1with a second intracellular protein as proposed for BTN3A1. The recognition of Ig superfamily proteins that function as sensors for intracellular processes would represent a new paradigm for “Ag” recognition by unconventional T cells. Because, if this is the case, there is no direct contact by the γδ TCR to its “Ags”, but instead, the TCR detects changes in the conformation or multimerization of the sensors. The challenge now is to identify the other proteins involved in the sensing process to confirm this hypothesis. Characterizing this sensing pathway will help determine how Vγ2Vδ2 T cells recognize the presence of intracellular pathogens. Elucidating the mechanism of stimulation will also help us understand how tumors such as Daudi and RPMI 8226 are recognized by the Vγ2Vδ2 TCR (1, 17) and allow us to identify tumors that would be highly sensitive to Vγ2Vδ2 T cell immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Grefachew Workalemahu and Mohanad Nada for helpful discussion. We thank Zhimei Fang for technical assistance. We thank Andrew Sandstrom and Erin Adams for providing coordinates for BTN3 structures. We thank Erin Adams, Eric Scotet, and Marc Bonneville for sharing data prior to publication.

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development (Grant 1 I01 BX000972-01A1) and the National Institute of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (Grant AR45504), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (Grant AI057160)), and the National Cancer Institute (Grant CA097274, University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Specialized Program of Research Excellence) to C.T.M, the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (Grant GM58442) to M.D.D., and by the Academy of Finland to J.M.

Abbreviations used in this article

- ApppI

triphosphoric acid 1-adenosin-5′-yl ester 3-(3-methylbut-3-enyl) ester

- BPH

bisphosphonate

- BrHPP

bromohydrin pyrophosphate (3-bromo-3-hydroxybutyl pyrophosphate)

- BTN

butyrophilin

- FDPS

farnesyl disphosphate synthase

- HMBPP

(E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate

- IDI

isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase

- IPP

isopentenyl pyrophosphate

- LC/MS

liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- β2M

β2-microglobulin

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PHA

phytohemagglutinin

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TRIM

tripartide motif

Footnotes

The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the granting agencies.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures: C. T. M. is a co-inventor of US Patent 8,012,466 on the development of live bacterial vaccines for activating γδ T cells. The other authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Morita CT, Jin C, Sarikonda G, Wang H. Nonpeptide antigens, presentation mechanisms, and immunological memory of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells: discriminating friend from foe through the recognition of prenyl pyrophosphate antigens. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hintz M, Reichenberg A, Altincicek B, Bahr U, Gschwind RM, Kollas AK, Beck E, Wiesner J, Eberl M, Jomaa H. Identification of (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate as a major activator for human γδ T cells in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:317–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puan KJ, Jin C, Wang H, Sarikonda G, Raker AM, Lee HK, Samuelson MI, Märker-Hermann E, Pasa-Tolic L, Nieves E, Giner JL, Kuzuyama T, Morita CT. Preferential recognition of a microbial metabolite by human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19:657–673. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Wilhelm M. γ/δ T-cell stimulation by pamidronate. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:737–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gober HJ, Kistowska M, Angman L, Jenö P, Mori L, De Libero G. Human T cell receptor γδ cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:163–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson K, Rogers MJ. Statins prevent bisphosphonate-induced γ,δ-T-cell proliferation and activation in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:278–288. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders JM, Ghosh S, Chan JMW, Meints G, Wang H, Raker AM, Song Y, Colantino A, Burzynska A, Kafarski P, Morita CT, Oldfield E. Quantitative structure-activity relationships for γδ T cell activation by bisphosphonates. J Med Chem. 2004;47:375–384. doi: 10.1021/jm0303709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Sarikonda G, Puan KJ, Tanaka Y, Feng J, Giner JL, Cao R, Mönkkönen J, Oldfield E, Morita CT. Indirect stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells through alterations in isoprenoid metabolism. J Immunol. 2011;187:5099–5113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Brenner MB. Human γδ T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: implications for innate immunity. Immunity. 1999;11:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson K, Rojas-Navea J, Rogers MJ. Alkylamines cause Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell activation and proliferation by inhibiting the mevalonate pathway. Blood. 2006;107:651–654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita CT, Beckman EM, Bukowski JF, Tanaka Y, Band H, Bloom BR, Golan DE, Brenner MB. Direct presentation of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human γδ T cells. Immunity. 1995;3:495–507. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang F, Peyrat MA, Constant P, Davodeau F, David-Ameline J, Poquet Y, Vié H, Fournié JJ, Bonneville M. Early activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell broad cytotoxicity and TNF production by nonpeptidic mycobacterial ligands. J Immunol. 1995;154:5986–5994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandes M, Willimann K, Moser B. Professional antigen-presentation function by human γδ T cells. Science. 2005;309:264–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1110267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita CT, Li H, Lamphear JG, Rich RR, Fraser JD, Mariuzza RA, Lee HK. Superantigen recognition by γδ T cells: SEA recognition site for human Vγ2 T cell receptors. Immunity. 2001;14:331–344. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato Y, Tanaka Y, Tanaka H, Yamashita S, Minato N. Requirement of species-specific interactions for the activation of human γδ T cells by pamidronate. J Immunol. 2003;170:3608–3613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarikonda G, Wang H, Puan KJ, Liu XH, Lee HK, Song Y, Distefano MD, Oldfield E, Prestwich GD, Morita CT. Photoaffinity antigens for human γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7738–7750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Bloom BR, Brenner MB, Band H. Vγ2Vδ2 TCR-dependent recognition of non-peptide antigens and Daudi cells analyzed by TCR gene transfer. J Immunol. 1995;154:998–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allison TJ, Winter CC, Fournié JJ, Bonneville M, Garboczi DN. Structure of a human γδ T-cell antigen receptor. Nature. 2001;411:820–824. doi: 10.1038/35081115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Band H, Brenner MB. Crucial role of TCRγ chain junctional region in prenyl pyrophosphate antigen recognition by γδ T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita S, Tanaka Y, Harazaki M, Mikami B, Minato N. Recognition mechanism of non-peptide antigens by human γδ T cells. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1301–1307. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyagawa F, Tanaka Y, Yamashita S, Mikami B, Danno K, Uehara M, Minato N. Essential contribution of germline-encoded lysine residues in Jγ1.2 segment to the recognition of nonpeptide antigens by human γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:6773–6779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita CT, Lee HK, Wang H, Li H, Mariuzza RA, Tanaka Y. Structural features of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphates that determine their antigenicity for human γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:36–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Fang Z, Morita CT. Vγ2Vδ2 T cell receptor recognition of prenyl pyrophosphates is dependent on all CDRs. J Immunol. 2010;184:6209–6222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei H, Huang D, Lai X, Chen M, Zhong W, Wang R, Chen ZW. Definition of APC presentation of phosphoantigen (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate to Vγ2Vδ2 TCR. J Immunol. 2008;181:4798–4806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harly C, Guillaume Y, Nedellec S, Peigné CM, Mönkkönen H, Mönkkönen J, Li J, Kuball J, Adams EJ, Netzer S, Déchanet-Merville J, Léger A, Herrmann T, Breathnach R, Olive D, Bonneville M, Scotet E. Key implication of CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A) in cellular stress sensing by a major human γδ T-cell subset. Blood. 2012;120:2269–2279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palakodeti A, Sandstrom A, Sundaresan L, Harly C, Nedellec S, Olive D, Scotet E, Bonneville M, Adams EJ. The molecular basis for modulation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cell responses by CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A)-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:32780–32790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.384354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abeler-Dörner L, Swamy M, Williams G, Hayday AC, Bas A. Butyrophilins: an emerging family of immune regulators. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compte E, Pontarotti P, Collette Y, Lopez M, Olive D. Frontline: Characterization of BT3 molecules belonging to the B7 family expressed on immune cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2089–2099. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morita CT, Parker CM, Brenner MB, Band H. TCR usage and functional capabilities of human γδ T cells at birth. J Immunol. 1994;153:3979–3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita CT, Verma S, Aparicio P, Martinez-A C, Spits H, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of human γ/δ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2999–3007. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spits H, Paliard X, Vandekerckhove Y, van Vlasselaer P, de Vries JE. Functional and phenotypic differences between CD4+ and CD4- T cell receptor-γδ clones from peripheral blood. J Immunol. 1991;147:1180–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka Y, Sano S, Nieves E, De Libero G, Roca D, Modlin RL, Brenner MB, Bloom BR, Morita CT. Nonpeptide ligands for human γδ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8175–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Lee HK, Bukowski JF, Li H, Mariuzza RA, Chen ZW, Nam KH, Morita CT. Conservation of nonpeptide antigen recognition by rhesus monkey Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3696–3706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jauhiainen M, Mönkkönen H, Räikkönen J, Mönkkönen J, Auriola S. Analysis of endogenous ATP analogs and mevalonate pathway metabolites in cancer cell cultures using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2967–2975. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolinsky TJ, Czodrowski P, Li H, Nielsen JE, Jensen JH, Klebe G, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W522–525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spada FM, Grant EP, Peters PJ, Sugita M, Melián A, Leslie DS, Lee HK, van Donselaar E, Hanson DA, Krensky AM, Majdic O, Porcelli SA, Morita CT, Brenner MB. Self recognition of CD1 by γ/δ T cells: implications for innate immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;191:937–948. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Cao R, Yin F, Lin FY, Wang H, Krysiak K, No JH, Mukkamala D, Houlihan K, Li J, Morita CT, Oldfield E. Lipophilic pyridinium bisphosphonates: potent γδ T cell stimulators. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:1136–1138. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roque AC, Lowe CR. Lessons from nature: on the molecular recognition elements of the phosphoprotein binding-domains. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:546–555. doi: 10.1002/bit.20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen A, Kroon PA, Poulter CD. Isoprenyl diphosphate synthases: protein sequence comparisons, a phylogenetic tree, and predictions of secondary structure. Protein Sci. 1994;3:600–607. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oldfield E, Lin FY. Terpene biosynthesis: modularity rules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:1124–1137. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sicard H, Ingoure S, Luciani B, Serraz C, Fournié JJ, Bonneville M, Tiollier J, Romagné F. In vivo immunomanipulation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with a synthetic phosphoantigen in a preclinical nonhuman primate model. J Immunol. 2005;175:5471–5480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sturm E, Bontrop RE, Vreugdenhil RJ, Otting N, Bolhuis RL. T-cell receptor γ/δ: comparison of gene configurations and function between humans and chimpanzees. Immunogenetics. 1992;36:294–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00215657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daubenberger CA, Salomon M, Vecino W, Hubner B, Troll H, Rodriques R, Patarroyo ME, Pluschke G. Functional and structural similarity of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in humans and Aotus monkeys, a primate infection model for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Immunol. 2001;167:6421–6430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen Y, Zhou D, Qiu L, Lai X, Simon M, Shen L, Kou Z, Wang Q, Jiang L, Estep J, Hunt R, Clagett M, Sehgal PK, Li Y, Zeng X, Morita CT, Brenner MB, Letvin NL, Chen ZW. Adaptive immune response of Vγ2Vδ2+ T cells during mycobacterial infections. Science. 2002;295:2255–2258. doi: 10.1126/science.1068819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan-Payseur B, Frencher J, Shen L, Chen CY, Huang D, Chen ZW. Multieffector-functional immune responses of HMBPP-specific Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in nonhuman primates inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes ΔactA prfA*. J Immunol. 2012;189:1285–1293. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar S, Hedges SB. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Martinez D, Scarlett UK, Rutkowski MR, Nesbeth YC, Camposećo-Jacobs AL, Conejo-Garcia JR. CD277 is a negative co-stimulatory molecule universally expressed by ovarian cancer microenvironmental cells. Oncotarget. 2010;1:329–338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamashiro H, Yoshizaki S, Tadaki T, Egawa K, Seo N. Stimulation of human butyrophilin 3 molecules results in negative regulation of cellular immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:757–767. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messal N, Mamessier E, Sylvain A, Celis-Gutierrez J, Thibult ML, Chetaille B, Firaguay G, Pastor S, Guillaume Y, Wang Q, Hirsch I, Nunès JA, Olive D. Differential role for CD277 as a co-regulator of the immune signal in T and NK cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3443–3454. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]