Abstract

This study aimed to characterize affective functioning in families of youth at high familial risk for depression, with particular attention to features of affective functioning that appear to be critical to adaptive functioning but have been underrepresented in prior research including: positive and negative affect across multiple contexts, individual and transactional processes, and affective flexibility. Interactions among early adolescents (ages 9-14) and their mothers were coded for affective behaviors across both positive and negative contexts. Primary analyses compared never-depressed youth at high (n=44) and low (n=57) familial risk for depression. The high risk group showed a relatively consistent pattern for low positive affect across negative and positive contexts at both the individual and transactional level. In contrast to prior studies focusing on negative affect that did not support disruptions in negative affect, the data from this study suggest variability by context: (i.e. increased negativity in a positive, but not negative, context) and individual vs. transactional processes (e.g., negative escalation). Findings are discussed in concert with attention to affect flexibility, contextual and transactional factors.

Keywords: Affect, Depression, High Risk, Youth, Interpersonal

Introduction

Early adolescence marks the start of a dramatic increase in depression rates (e.g., Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001), and youth at high familial risk for depression–defined as youth with a biological parent who has reported experiencing at least one clinical episode of depression–are particularly vulnerable. Relative to low risk peers, youth at high familial risk evidence a 3-4 fold increased risk for developing depression (Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998), with the highest period of incidence occurring during the adolescent period (Weissman et al., 2006). Depressive disorders are often severe in this population, including an earlier age of onset, longer duration of episodes, higher social impairment, and higher rates of suicide relative to other depressed adolescents (Beardslee, Keller, Lavori, & Staley, 1993).

Affective functioning (defined as motivational, behavioral, and subjective aspects of emotions) in the family context appears to represent a critical dimension of this high risk profile. Patterns of familial affective functioning may reflect the presence of subdiagnostic or clinical symptoms among one or more family members, and/or may be one pathway through which maladaptive affect regulation tendencies are transmitted to vulnerable youth through modeling, social contingencies, or transactional co-regulatory processes (e.g., Silk, Shaw, Forbes, Lane, & Kovacs, 2006). The goal of this study was to provide a thorough characterization of several aspects of affective functioning among families of early adolescents at high familial risk for depression as a means to provide insights into affective processes that reflect elevated risk, and may serve as key targets for prevention or early intervention.

Families of Youth with Depression

Previous research has indicated support for a variety of disruptions in affective functioning among families of youth with depression. For example, mothers tend to show greater displays of negative affect, and conflict, as well as lower social support and positive affect in problem solving interactions with depressed youth. Depressed youth generally show elevated negative affect and reduced positive affect (e.g., Dietz et al., 2008; Sheeber, Allen et al., 2009). There are also transactional processes whereby youth and parent affective behaviors build from one another; e.g., when depressed youth display dysphoric affect during problem solving interactions, mothers show facilitative responses while fathers reduce aggressive behavior (Sheeber, Hops, Andrews, Alpert, & Davis, 1998). Although much work will be required to disentangle these complicated patterns of interaction, at least some of these patterns are concurrently (for review and meta-analysis, see McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007) and prospectively (e.g., Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews, 1997) related to youth symptoms, highlighting the importance of familial affective functioning as it relates to depression.

Parents and Youth at High Familial Risk for Depression

A key question has been whether or not these apparently maladaptive patterns in familial affective functioning predate the development of depressive symptoms among early adolescents at high familial risk for depression. If so, an understanding of such patterns may provide a platform for early prevention among this vulnerable population. Studies of high risk young children indicate disruptions in features of both positive and negative affective functioning among mothers with current or past depression (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000) and their children (e.g., Hart, Field, del Valle, & Pelaez-Nogueras, 1998; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998). Despite theoretical interest (Silk et al., 2007; Yap, Allen, & Sheeber, 2007), empirical data in high risk adolescent families are more limited. The few existing studies have generally focused on behaviors of mothers with current or past depression, and found greater criticism, high negative and low positive affect in their interactions with their adolescent offspring (Frye & Garber, 2005; Hamilton, Jones, & Hammen, 1993; Hops et al., 1987; Nelson, Hammen, Brennan, & Ullman, 2003; Stein et al., 2000). Importantly, as previously noted by Birmaher et al.(2004), the majority of youth in these families had already developed depression or other psychopathology that may have contributed to these maternal behaviors through transactional processes. Birhmaher (2004) addressed these concerns with semi-structured interview data that assessed self-reported interactions between mothers, fathers, and high risk asymptomatic adolescents, as well as depressed and healthy control adolescents (ages 12-17). The data showed no differences among asymptomatic adolescents and their mothers or fathers, relative to healthy controls, while data supported several disruptions among families of youth with depression (e.g., lower global warmth and greater global tension). However, in a recent report from the same program of research, Dietz et al. (2008), found that in observational data from mother-youth interactions primed for conflict, mothers in both the asymptomatic high risk and depressed sample showed patterns of greater withdrawal from interactions. Also, asymptomatic high risk youth showed less positivity than healthy control youth, but they did not differ from controls in negativity (depressed youth showed greater negativity and less positivity relative to both groups). These findings underscore the importance of using observational methods to assess familial affective functioning, as well as the importance of attending to features of positive affect. Also, these data suggest a need to further understand negative affective functioning as these two studies reporting null findings among high risk early adolescents (Birmaher, et al., 2004; Dietz, et al., 2008) are inconsistent with research among younger children at high familial risk (e.g., Field, Healy, Goldstein, & Guthertz, 1990; Hops, et al., 1987; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998).

Improving our Understanding by Evaluating Key Features of Affective Functioning

Healthy affective functioning is not represented by minimizing negative affect and maximizing positive affect, but rather by flexibly modulating affect and responding to changing contextual demands and opportunities to reach short and long term goals. Yet, to date, studies of affective functioning in these high risk families primarily have focused on negative affect; on single contexts primed for conflict or problem solving; and on affect at the individual level. These approaches have yielded useful data, but may limit our ability to understand how adaptively high risk youth and parents are navigating a complex emotional world. As such, prior results may be clarified and extended by evaluating features of affective functioning that are often overlooked, but are functionally important: a) positive affective functioning, b) contextual factors and affective flexibility, c) transactional parent-child affective processes (e.g. negative escalation).

Positive Affective Functioning

Recent literature suggests that positive affective functioning is an important area of investigation that may be particularly relevant to understanding risk for depression (e.g., Davey, Yucel, & Allen, 2008; Pine, Cohen, Cohen, & Brook, 1999). Depressive disorders include deficits in positive affective functioning at the individual level across cognitive (Beevers & Meyer, 2002; Cropley & MacLeod, 2003), behavioral (Lewinsohn & Graf, 1973; Sloan, Strauss, Quirk, & Sajatovic, 1997), motivational (Forbes, Shaw, & Dahl, 2007; Kasch, Rottenberg, Arnow, & Gotlib, 2002), subjective/experiential (e.g., Bylsma, Morris, & Rottenberg, 2008), and neurobiological (Forbes & Dahl, 2005; Henriques & Davidson, 2000) systems. Evidence suggests some similar deficits among high risk samples prior to the onset of symptoms (Gotlib et al., 2010). These deficits are functionally important as positive affect is crucial to healthy socio-emotional (Fredrickson, 1998), cognitive (e.g., Isen, 1999) and physical (e.g., Salovey, Detweiler, Steward, & Bedell, 2001) functioning, and may help to regulate negative affect or mood (e.g., Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Yet, we know little about positive affective functioning at the family level among high risk youth. Dietz et al. (2008) present some of the only data regarding low positive affect in problem solving interactions among early adolescents prior to the onset of symptoms. However, Silk et al. (2006) also reported on observational data among children of depressed mothers that indicated that child reward anticipation in a mother-child interaction task uniquely moderated the association between maternal depression and child internalizing problems. Moreover, two recent studies–one of a non-clinical sample (Yap, Allen, & Ladouceur, 2008) and one of depressed youth (Sheeber, Allen, et al., 2009)–have demonstrated that aberrant positive affective functioning among both mothers and adolescents is related to depressive symptoms. Taken together, these data point to the need to understand positive affective functioning—including transactional processes—in the context of high familial risk for depression.

Contextual Factors and Affective Flexibility

Affective norms vary based on context such that, for example, expressing increased negative affect in the context of conflict may carry different implications than a tendency to express increased negative affect in a positive context. Moreover, there may be important group differences in affective flexibility or responses to changing contextual demands and opportunities. For example, individuals with depression tend to get stuck in, or sustain, negative affective states even following the removal of negative stimuli (Sheeber, Allen, et al., 2009; Siegle, Steinhauer, Thase, Stenger, & Carter, 2002), and they have trouble activating and sustaining positive affective states in response to positive stimuli (Heller et al., 2009; Sloan, Strauss, & Wisner, 2001). It follows that at the family level, high risk youth and their parents may become entrenched in negative affective spirals, and have difficulty switching into positive affective states in response to contextual opportunities for positive experiences.

At least two (complementary) theories point to the critical role of context when understanding affective processes, and may provide a framework for understanding these affective patterns. Emotion Context Insensitivity (Bylsma, et al., 2008) describes that depressed individuals show reduced emotion reactivity to changing environmental contexts, while Emotion Inertia Theory (Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2010) emphasizes that such reduced reactivity to context reflects a tendency to be resistant to emotional change (one's current emotion state is highly predicted by their state a moment before) and to show a decoupling of emotion state and context.

Despite all of these indications that contextual factors are critical to understanding affective functioning (including affective flexibility), the majority of observational research focuses on contexts primed for conflict. A few studies have recently examined parent-youth interactions in a positive context, with results suggesting that valuable information can be obtained by this approach (Sheeber, Allen, et al., 2009; Whittle et al., 2009; Yap, et al., 2008). This study examines affective functioning among high risk youth and their mothers in conflictual and positive contexts, as well as through contextual transitions. Findings may yield important information about whether or not high risk families struggle to manage features of positive and negative affect as a means to manage conflict, to capitalize on positive experiences, to flexibly transition between contexts, or all of these.

Individual and Transactional Processes

Finally, prior studies tend to focus on youth or parent affective functioning, with little attention to the transactional processes that literature shows occur between mothers and their offspring through infancy and early childhood (e.g., Tronick, 1989), and likely occur in adolescence. Although Dietz et al. (2008) carefully considered both parent and youth affective behaviors to capture contributions from both parties, transactional processes may also occur at the dyadic level. For example, a transactional escalation of negative affect may characterize high risk youth and parents as they exacerbate each others negativity and struggle to employ skills to deescalate the cycle. In fact, a recent study in a non-clinical community sample indicates some support for this idea as those youth and parents who showed reciprocal negative exchanges were more likely to develop depression in the following year (Schwartz et al., 2011). Moreover, given evidence in families of depressed youth that positive affect is not only attenuated but also brief in duration (Sheeber, Allen, et al., 2009), positive affect may fail to escalate and build at the transactional level. The current study observed affective behaviors at the individual and dyadic level to capture key transactional processes.

Study Overview

This study examined affective functioning among early adolescents at high and low familial risk for depression, and their mothers, interacting in contexts primed for conflict and positivity. We hypothesized that mothers and youth at high familial risk for depression, relative to a low risk group, would evidence less positive affective behavior across both negative and positive contexts. Also, although Dietz et al. (2008) did not find differences in youth negative affective behavior in a conflictual context, a wealth of data among families with younger children at high risk for depression suggest aberrant negative affective functioning (e.g., Field, et al., 1990; Hops, et al., 1987; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998) such that we hypothesized greater negative affective behavior across contexts for both mothers and youth. We also hypothesized that mother-youth dyads would display greater transactional negative affective behavior and less transactional positive affective behavior, relative to low risk dyads. Finally, we hypothesized that high risk youth and mothers would show poor affective flexibility when transitioning across negative and positive contexts.

Method

Participants

One-hundred and one early adolescents (43 male, 58 female) participated in this study with their biological mothers. Youth ranged in age from 9 to 14 (M = 11.51, SD = 1.72) and mothers ranged in age from 29 to 55 (M = 42.34, SD = 5.93). Forty-seven youth were offspring of depressed mothers who had experienced an episode of Major Depressive Disorder within the past two years (High-Risk; HR) and 54 youth were offspring of mothers with no lifetime history of psychiatric disorder (Low-Risk; LR). All HR mothers were required to meet DSM-IV criteria (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) for chronic (lasting more than 1 year) or recurrent (minimum of two episodes) Major Depressive Disorder, with the most recent episode occurring within two years. All LR mothers were required to report a lifetime-history free of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. Additional exclusion criteria for mothers in the HR group were any history of mania or obsessive-compulsive disorder and current substance abuse.

Offspring were excluded from the study if they had learning disabilities or developmental disorders that could limit their ability to understand or complete study procedures. Because the study also involved a psychophysiological component, we excluded youth with motor or other neurological problems, major medical disorders, and those who were taking psychotropic medications. Because the LR group was intended as a comparison group with no psychiatric diagnoses, LR offspring were excluded if they met DSM-IV criteria for any current or past Axis I diagnoses. HR offspring were excluded if they met criteria for a current or past diagnosis of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance abuse, or psychotic disorder. In order to recruit a representative group of HR offspring, we allowed HR offspring to participate in the study if they had an anxiety disorder (N = 5; 3 with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 2 with Social Phobia) or behavioral disorder (N = 9; 6 with ADHD, 1 with CD, 1 with ODD, and 1 with comorbid ADHD and ODD), which are quite prevalent in this population (Weissman, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Verdeli, & Pilowsky, 2005). Additional demographic information is provided in Table 1, which shows that HR and LR groups did not differ in race, mother's education, child age, child gender, or child depressive symptoms (self report on Child Depression Inventory).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Low Risk (n = 54) | High Risk (n = 47) | t/χ 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Age, M (SD) | 11.74 (1.78) | 11.26 (1.63) | t[99] = 1.421 |

| Youth Gender, % Female | 59 | 55 | χ2 [1] = .161 |

| Youth Race, % White, African American, Other | 80%, 17%, 4% | 64%, 34%, 2% | χ2 [2] = 4.141 |

| Mother's Education , % | |||

| Graduate/Professional, College, High School, Did not finish High School | 25%, 60%, 13%, 2% | 9%, 72%, 13%, 6% | χ2 [3] = 5.561 |

| Child Depressive Symptoms (Child Depression Inventory), M (SD) | 4.31 (6.25) | 5.98 (6.40) | t[99] =- 1.321 |

Alpha level greater than .05.

Offspring were excluded from the study if they had learning disabilities or developmental disorders that could limit their ability to understand or complete study procedures. Because the study also involved a psychophysiological component, we excluded youth with motor or other neurological problems, major medical disorders, or were taking psychotropic medications. Because the LR group was intended as a comparison group with no psychiatric diagnoses, LR offspring were excluded if they met DSM-IV criteria for any current or past Axis I diagnoses. HR offspring were excluded if they met criteria for a current or past diagnosis of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance abuse, or psychotic disorder. In order to recruit a representative group of HR offspring, we allowed HR offspring to participate in the study if they had an anxiety disorder (N = 5; 3 with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 2 with Social Phobia) or behavior disorder (N = 9; 6 with ADHD, 1 with CD, 1 with ODD, and 1 with comorbid ADHD and ODD), which are highly prevalent in this population (Weissman, et al., 2005). Additional demographic information is provided in Table 1, which shows that HR and LR groups did not differ in race, mother's education, child age, child gender, or child depressive symptoms (self report on Child Depression Inventory).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the general community in a metropolitan area in the northeastern region of the United States through flyers, newspaper/radio advertisements, and a university-sponsored telephone recruitment service. HR families were also recruited from outpatient clinics at the university hospital. Interested families completed a 15-minute telephone screen to assess maternal and child psychiatric symptomatology and other inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 608 families completed a telephone screen, and 420 dyads were screened out based on their responses to the telephone screen. The remaining 188 dyads were invited to the lab to complete diagnostic interviews to confirm parent and child DSM-IV diagnoses. Following these procedures, 103 dyads met full criteria and were enrolled in the study. After obtaining parent consent and child assent, parent-child dyads completed a battery of questionnaires and participated in a series of tasks, including behavioral observation of parent-child interaction. Two dyads did not complete the observation tasks due to technical problems, leading to a final sample of 101.

Instruments

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

The SCID (First & Gibbon, 2004) is a clinician administered interview assessing lifetime and current psychiatric disorders among mothers. The SCID was administered by trained interviewers. Inter-rater reliability was calculated on presence or absence of lifetime or current diagnoses among a random sample of 18% of interviews and yielded no disagreements (kappa = 1.0).

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia in School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL)

The KSADS-PL (Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, & Rao, 1997) assesses lifetime and current psychiatric disorders among youth. Parents and youth were interviewed separately, with trained interviewers integrating data from both to arrive at a final diagnosis. Inter-rater reliability was calculated on presence or absence of lifetime or current diagnoses among a random sample of 27% of interviews and yielded no disagreements (kappa = 1.0).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

Data were also collected on current depressive symptomatology using the BDI (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). The BDI is a well-established 21-item measure designed to assess current depressive symptomatology among clinically referred or community samples of adults.

Demographics

A demographics questionnaire was used to assess child and parent age, gender, race, education, and family income.

Dyadic interactions

Conflict Task

Dyads completed a “hot topics” task designed to elicit conflict and negative emotion (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). First, mothers and youth completed a checklist of common areas of conflict among youth-parent dyads. Dyads were asked to discuss the conflict rated most highly by both members of the dyad during an eight minute videotaped discussion. They were given a card with the conflict listed and asked to address the following points: (1) how recent disagreements started (2) who else was involved (3) how the issue ended, and (4) how the dyad would deal with the issue in the future. The discussion points were included to help dyads that could not think of anything to say.

Plan a Fun Activity Task

Following the conflict task, dyads were asked to jointly plan a fun activity that they could do together in the next week (Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Snyder, 2004). This task was designed to elicit mutual positive affect. Dyads were instructed to choose something that they would both enjoy and plan it in as much detail as possible. The dyad was filmed for 5 minutes while planning the activity. The order of the tasks was fixed (Conflict followed by Plan a Fun Activity) because we were specifically interested in whether depressed mothers would have difficulty transitioning from a negative to a positive context.

Interactional Dimensions Coding System-Revised (IDCS-R)

Interactions were coded using the IDCS-R, which is a macro-analytic observational coding system originally designed to assess couples’ interactions (Julien, Markman, & Lindahl, 1989), and later modified and applied successfully to adolescent interactions with mothers, peers and romantic partners (Furman & Shomaker, 2008). Trained coders provide a rating on a five-point Likert scale with half-point intervals (1 extremely uncharacteristic to 5 extremely characteristic) for each of 15 different affective behaviors. “Affective behavior” codes are construed of a simultaneous consideration of observed body positions, facial expressions, tone of voice, and/or verbal content. For example, Support Validation may include a calm and pleasant voice tone, leaning in toward partner, touching their arm gently, and making statements such as, “I understand what you're saying...[.]” Ten of these 15 codes capture affective behaviors at the individual level (adolescent and parent are coded separately, e.g. withdrawal) and 5 codes capture affective behavior at the transactional or dyadic level (5 scales on which the adolescent and mother coded as one unit; e.g. negative escalation). In order to minimize the number of statistical tests and most precisely address our hypotheses regarding how mothers and youth manage affect in contexts of conflict and positivity, we made an a priori selection of 10 of the 15 codes most relevant to our questions (including, for example, Positive Affect and Support Validation; and excluding, for example, Task Avoidance). See Tables 2, 3 and 4 for the 7 individual codes, and 3 dyadic codes evaluated in the current study, as well as their means and standard deviations across contexts. To minimize halo effects, the two contexts were never coded during the same coding session for the same participants. Tasks were randomly assigned to trained coders who were naive to participant information. Inter-rater agreement was checked on 23% of tasks (for each of three coders relative to the “reliability coder”). Intra-class correlation coefficients for the 10 codes ranged from .71 to .90 (mean= .79; standard deviation = .05).

Table 2.

Conflictual Context: Multivariate tests of individual positive and negative affective behaviors comparing high risk and low risk youth/parent

| Low Risk Youth | High Risk Youth | Youth Effect Size | Youth F Statistic | Low Risk Parent | High Risk Parent | Parent Effect Size | Parent F Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDCS-R Individual Codes | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) |

| PAB | d=.72 | 4.08 (3,95)* | d=.87 | 5.92 (3,95)** | ||||

| Positive Affect | 3.10 (0.60) | 2.72 (0.67) | d=.66 | 10.38 (1,97)** | 3.50 (0.56) | 3.05 (0.66) | d=.79 | 15.11 (1,97)*** |

| Problem Solving | 2.73 (0.63) | 2.51 (0.65) | d=.36 | 3.19 (1,97) | 3.56 (0.62) | 3.40 (0.74) | d=.27 | 1.88 (1,97) |

| Support Validation | 2.81 (0.62) | 2.64 (0.61) | d=.30 | 2.17 (1,97) | 3.56 (0.63) | 3.17 (0.76) | d=.64 | 9.90 (1,97)** |

| NAB | d=.45 | 1.20 (4,94) | d=.48 | 1.37 (4,94) | ||||

| Negative Affect | 2.18 (0.59) | 2.18 (0.55) | d=.06 | .08 (1,97) | 1.75 (0.65) | 1.94 (0.58) | d=.38 | 3.56 (1,97) |

| Dominance | 1.40 (0.58) | 1.26 (0.45) | d=.22 | 1.16 (1,97) | 1.86 (0.77) | 2.08 (0.70) | d=.31 | 2.43 (1,97) |

| Conflict | 1.65 (0.75) | 1.52 (0.65) | d=.06 | .12 (1,97) | 1.48 (0.71) | 1.60 (0.5) | d=.25 | 1.52 (1,97) |

| Withdrawal | 1.83 (0.60) | 2.04 (0.61) | d=.41 | 4.06 (1,97) | 1.10 (0.33) | 1.22 (0.39) | d=.20 | 3.13 (1,97) |

Note: PAB= positive affective behaviors, NA=negative affective behaviors

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Conflict and Positive Context: Multivariate tests of dyadic positive and negative affective behaviors comparing high risk and low risk youth/parent

| Conflict Low Risk | Conflict High Risk | Conflict Effect Size | Conflict F Statistic | Positive Low Risk | Positive High Risk | Positive Effect Size | Positive F Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDCS-R Dyadic Codes | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) |

| PAB | d = 71 | 6.12 (2,96)** | d= .61 | 4.44 (2,96)* | ||||

| Positive Escalation | 2.54 (0.89) | 2.04 (0.71) | d = 63 | 9.77 (1,99)** | 2.55 (0.70) | 2.27 (0.85) | d= .39 | 3.73 (1,99) |

| Mutuality | 3.36 (0.82) | 2.90 (0.78) | d = 59 | 8.43 (1,99)** | 3.35 (0.79) | 2.94 (0.75) | d= .61 | 8.97 (1,99)* |

| NAB | ||||||||

| Negative Escalation | 1.66 (0.64) | 1.88 (0.68) | d = 43 | 4.55 (1,99)* | 1.55 (0.70) | 1.82 (0.69) | d= .48 | 5.70 (1,99)* |

Note: PAB = positive affective behaviors, NAB = negative affective behaviors.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 4.

Positive Context: Multivariate tests of individual positive and negative affective behaviors comparing high risk and low risk youth/parent

| Low Risk Youth | High Risk Youth | Youth Effect Size | Youth F Statistic | Low Risk Parent | High Risk Parent | Parent Effect Size | Parent F Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDCS-R Individual Codes | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Cohen's d | F (df) |

| PAB | d=.59 | 2.77 (3,95)* | d=.80 | 5.08 (3,95)** | ||||

| Positive Affect | 3.28 (0.52) | 2.99 (0.80) | d=.50 | 6.11(1,97)* | 3.52 (0.52) | 3.14 (0.58) | d=.78 | 14.82 (1,97)*** |

| Problem Solving | 3.03 (0.60) | 2.86 (0.63) | d=.36 | 3.14(1,97) | 3.51 (0.64) | 3.28 (0.62) | d=.53 | 6.87 (1,97)* |

| Support Validation | 3.01 (0.59) | 2.66 (0.76) | d=.57 | 7.91 (1,97)** | 3.54 (0.64) | 3.15 (0.65) | d=.71 | 12.28 (1, 97)** |

| NAB | d=.56 | 1.81 (4,94) | d=1.02 | 6.08 (4,94)** | ||||

| Negative Affect | 1.97 (0.59) | 2.23 (0.57) | d=.52 | 6.69 (1,97) | 1.70 (0.52) | 1.99 (0.49) | d=.69 | 11.46 (1, 97)** |

| Dominance | 1.28 (0.43) | 1.28 (0.39) | d=.11 | .25 (1,97) | 1.50 (0.57) | 1.88 (0.59) | d=.67 | 11.08 (1, 97)** |

| Conflict | 1.44 (0.64) | 1.59 (0.77) | d=.35 | 3.00 (1,97) | 1.28 (0.43) | 1.49 (0.64) | d=.52 | 6.67 (1, 97)* |

| Withdrawal | 1.68 (0.56) | 1.90 (0.81) | d=.33 | 2.73 (1,97) | 1.19 (0.37) | 1.49 (0.64) | d=.76 | 13.79 (1, 97)*** |

Note: PAB = positive affective behaviors, NAB = negative affective behaviors.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Analytic Plan

To examine differences between the high and low risk groups in negative and positive affective behaviors in each of the two contexts while reducing Type 1 error, we conducted a series of one-way, between group (low risk, high risk) Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) tests (with age and gender as covariates--see Preliminary Analyses below for rationale) where dependent variables included each of three families of codes (dependent variables) in two contexts (total of 6 MANCOVA tests): positive affective behaviors (Positive Affect, Problem Solving, Support Validation), negative affective behaviors (Negative Affect, Dominance, Conflict and Withdrawal), and dyadic positive affective behaviors (Positive Escalation, Mutuality). When the Wilks’ Lambda statistic for the multivariate test was significant, we went on to explore individual codes within that family as a means to provide more specific information about the quality of the positive or negative affective behaviors to inform future research. Dyadic negative affective behavior (Negative Escalation) was examined in a One-way, between-group Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) given that there was only one code in this group. To examine affective flexibility (change in affective behaviors in response to a change in context), we conducted a series of 2 (context: conflictual context, positive context) × 2 (group: high risk, low risk) repeated measures ANCOVAs with positive and negative affective behaviors as dependent variables. We focused exclusively on interpreting the interactions in the repeated measures analyses because they were relevant to our specific hypotheses. We did not re-interpret main effects in these repeated measures analyses because this would have been redundant with the above (more stringent) MANCOVA tests which were used to examine the first 6 hypotheses while reducing Type 1 error.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

One-way ANOVA and chi-square tests revealed that there were no gender, age, or race differences between groups (see test statistics in Table 1). However, affective variables did vary by gender and age, as also described in studies of observed affect in similar populations (e.g., Silk, Shaw, Skuban, Oland, & Kovacs, 2006; Yap, et al., 2008). As such, gender and age were included as covariates in all MANCOVA analyses. Given the somewhat broad age range (9-14) of the participants in the current study, we also re-ran primary analyses with a group × age interaction term included. These analyses suggested that although the dependent variables (affect codes) differ by age, the effects of risk status on dependent variables (affect codes) were not affected by age (i.e. no interaction effects). Also, given that some youth in the high risk group had a diagnosable anxiety disorder (n=5) or behavior disorder (n= 9) which could impact affective behavior, we also conducted all analyses while excluding these participants. Finally, we conducted all analyses with continuous depression scores (BDI and CDI for parents and youth, respectively) as covariates to see how they related to outcomes of interest. Results for all of these analyses were similar in patterns and direction such that results reported below are from the full sample. Details of these additional analyses are available from first author.

Positive and Negative Affective Behavior in Conflictual Contexts

Hypothesis 1: High risk youth will show greater negative affective behavior (1a) and less positive affective behavior (1b) in a context primed for conflict

Hypothesis 1a was not supported as the Wilks’ Lambda multivariate test of overall between group differences was not statistically significant for negative affective behavior (see Table 2). In support of hypothesis 1b, Wilks’ Lambda for positive affective behavior was significant. Univariate tests of specific behaviors revealed that positive affect was significantly lower for youth in the high risk group, while there was no support for a group difference in problem solving or support validation.

Hypothesis 2: Mothers of high risk youth will show greater negative affective behavior (2a) and less positive affective behavior (2b) in a context primed for conflict

Hypothesis 2a was not supported as the Wilks’ Lambda multivariate test of overall between group differences was not statistically significant for negative affective behavior (see Table 2). In support of hypothesis 2b, Wilks’ Lambda for positive affective behaviors was significant. Univariate tests revealed that positive affect and support validation were significantly lower for parents of youth in the high risk group, while problem solving did not differ between groups.

Hypothesis 3: High risk mother-youth dyads will show greater dyadic negative affective behavior (3a) and less dyadic positive affective behavior (3b) in a context primed for conflict

In support of hypothesis 3a, one-way ANOVA revealed that the high risk parent-youth dyads showed greater negative affective escalation than low risk dyads (see Table 3). In support of hypothesis 3b, Wilks’ Lambda multivariate test of overall between group differences was statistically significant for dyadic positive affective behaviors. Univariate tests revealed that both positive escalation and mutuality were significantly lower for parent-youth dyads in the high risk group, relative to the low risk group.

Positive and Negative Affective Behavior in Positive Contexts

Hypothesis 4: High risk youth will show more negative affective behavior (4a) and less positive affective behavior (4b) in a context primed for positivity

Results did not support hypothesis 4a in that Wilks’ Lambda for negative affective behaviors was not statistically significant (see Table 4). However, in support of hypothesis 4b, Wilk's Lambda for positive affective behaviors was significant. Univariate tests revealed that positive affect and support validation were significantly lower for youth in the high risk group, relative to the low risk group, in a positive context (there was a trend in the same direction for problem solving).

Hypothesis 5: Mothers of high risk youth will show more negative affective behavior (5a) and less positive affective behavior (5b) in a context primed for positivity

Results supported hypothesis 5a in that Wilks’ Lambda for negative affective behaviors in a context primed for positivity was statistically significant (see Table 4). Univariate tests revealed that the high risk group, relative to the low risk group, had higher scores on each of the negative affective behavior codes: negative affect, dominance, conflict and withdrawal. In support of hypothesis 5b, Wilk's Lambda for positive affective behaviors was significant. Univariate tests revealed that the high risk group, relative to the low risk group, had lower scores on each of the positive affective behavior codes: positive affect, problem solving, and support validation.

Hypothesis 6: High risk parent-youth dyads will show more transactional negative affect escalation (6a) and less transactional positive affect escalation (6b) in a context primed for positivity

Results were in support of hypothesis 6a such that a One-way between group ANOVA revealed significantly higher scores for negative escalation among the high risk group, relative to the low risk group, in a context primed for positivity (see Table 3). In support of hypothesis 6b, Wilk's Lambda for transactional positive affective behaviors was significant. Between-group univariate tests revealed that relative to the low risk group, the high risk group had higher scores on mutuality, and a trend toward higher scores on positive affect escalation.

Transitioning from Conflict to Positivity

Hypothesis 7: High risk youth will show less affective flexibility--defined by an increase in positive affective behavior (7a) and a decrease in negative affective behavior (7b) when switching from a context primed for conflict to a context primed for positivity

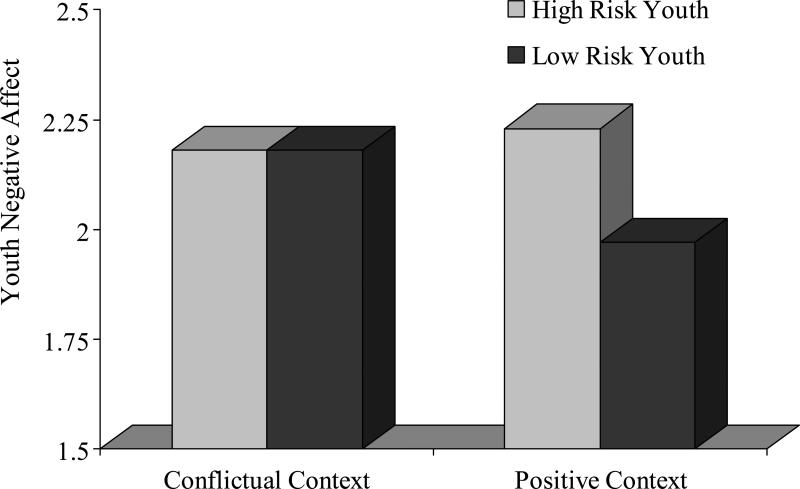

In partial support of hypothesis 7a, a series of 2 (low risk, high risk) × 2 (conflictual context, positive context) repeated measures ANOVAs revealed a significant group by time interaction for negative affect, F(1, 97) = 5.27, p =.02, d = .45, and conflict, F(1, 97) = 4.33, p =.04, d = .43; and no significant interaction for dominance, F(1, 97) = 2.22, p =.14, d = .29, or withdrawal, F(1, 97) = .001, p = .97, d = .00. As depicted in Figure 1, the differences are characterized by a reduction in negative affect and conflict when transitioning from the conflictual to positive context among the low risk youth, while the high risk youth remain the same or are slightly increasing. There were no significant group by time interactions for change in positive affective behavior from the context primed for conflict to the context primed for positivity: positive affect, F(1, 97) = .28, p =.60, d=.14; problem solving, F(1, 97) = .02, p =.90, d = .06; support/validation, F(1, 97) = 2.66, p = .11, d = .31.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs depict levels of observed negative affect among youth at high and low familial risk for depression in negative and positive contexts. Low risk youth show a reduction in negative affect when transitioning from a negative to a positive context, while high risk youth do not

Hypothesis 8: Mothers of high risk youth will show less affective flexibility--defined by an increase in positive affective behavior (8a) and a decrease in negative affective behavior (8b) when switching from a context primed for conflict to a context primed for positivity

In partial support of hypothesis 8a, a series of 2 (low risk, high risk) × 2 (conflictual context, positive context) repeated measures ANOVAs revealed a significant group by time interaction for withdrawal, F (1, 97) = 5.87, p =.02, d =.47. The interaction is characterized by a reduction in withdrawal when transitioning from the conflictual to positive context among the parents of low risk youth, while the parents of high risk youth remain the same or are slightly increasing. There were no group by time interactions for negative affect, F (1, 97) = .93, p =.34, d = .11; conflict, F (1, 97) = .63, p =.43, d = .11; or dominance, F(1,97) = 1.13, p =.29, d = .00. There were no significant group by time interactions for change in positive affective behaviors from the conflictual to positive contexts: positive affect, F(1, 97)= .21, p = .65, d = .19; problem solving, F(1, 97) = .82, p =.37, d =.14; support/validation: F(1, 97) = .005, p =.94, d = .23 from the conflictual to positive contexts.

Hypothesis 9: High risk mother-youth dyads will show less affective flexibility--defined by an increase in transactional positive affective behaviors (9a) and a decrease in transactional negative affective behaviors (9b) when switching from a context primed for conflict to a context primed for positivity

There was no support for hypotheses 9a and 9b, as indicated by a series of 2 (low risk, high risk) × 2 (conflictual context, positive context) repeated measures ANOVAs yielding nonsignificant statistics for negative escalation, F (1, 99) = .14, p=.71, d =.26; positive escalation, F(1, 97)= .1.37, p = .25, d = .25; and mutuality, F(1, 97) = .003, p=.96, d = .06.

Discussion

The current study examined affective functioning among youth at high and low familial risk for depression, and their mothers. The study considered key features of affective functioning that are underrepresented in research including the examination of negative and positive affective behaviors; conflictual and positive contexts; affective flexibility in response to changing contextual demands and opportunities; and both individual and transactional processes.

The most consistently and robustly supported hypotheses revealed disruptions in positive affective functioning among the high risk group—findings held across both conflictual and positive contexts, and were present among parents and youth at both the individual and transactional level. Disruptions in negative affective functioning were more variable. For example, although negative affective behaviors at the individual level did not differ between groups in the conflictual context, there was support for a transactional process of negative escalation that was unique to the high risk group. These data suggest that high risk youth and mothers are not characterized by greater negativity in conflictual contexts, per se, but rather by the transactional escalation (a snowballing of “I'm negative, you're negative back.”). Moreover, negative affective behaviors were elevated (at the individual level for mothers but not youth, and at the transactional level) in the positive context, relative to the low risk group. Furthermore, there was evidence that high risk youth and their mothers were less likely to reduce certain negative affective behaviors when transitioning from a conflictual to a positive context. This may suggest a lack of sensitivity to changing contexts in general, and/or a lack of flexibility in responding to contextual opportunities for positive experiences more specifically. These findings regarding positive and negative affective functioning are best understood in concert with one another, and with attention to contextual and transactional processes, as elaborated below.

The finding that conflictual contexts among high risk youth and their mothers were characterized by aberrant positive affective functioning is consistent with data reported by Dietz et al. (2008). With regard to specific behaviors, the ability to problem solve did not differ between groups, while positive affect (mothers and youth) and support validation (mothers) were lower for the high risk group. There was also support for disruptions in the tendency to transactionally build positivity (positive escalation) over the course of the conflictual context, and for the tendency to appear “in synch” (mutuality). Although null findings regarding negative affective behaviors in the context of conflict are consistent with Dietz et al.(2008), they are surprising given research on families of young children at risk for depression suggesting disruptions in negative affective functioning (e.g., Field, et al., 1990; Hops, et al., 1987; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998). It may be that the normative increase in negative affect and family conflict during the adolescent period (e.g., Flannery, Montemayor, Eberly, & Torquati, 1993) eliminates this distinction among groups. In addition, support for negative escalation in the high risk group may shed light on this discrepancy. Perhaps it is not the presence of negative affect, per se, that is problematic, but rather the tendency for youth and mothers to engage in poor mutual regulation of negative affect. This interpretation also relates to literature suggesting that youth and adults with depression tend to experience more sustained negative affective states (Sheeber, Allen, et al., 2009; Siegle, et al., 2002). Negative escalation may reflect a transactional tendency towards sustained negative affective states, and/or a failure to engage or model appropriate regulatory strategies to curtail negative affect. These family-level tendencies may be internalized by youth over time.

To date, there are no studies, to our knowledge, that report on positive affect in contexts primed for positivity among adolescents at high familial risk, and their mothers, prior to the development of depressive symptoms. Both high risk youth and their mothers demonstrated aberrant patterns of positive affective functioning at the individual and transactional level when asked to plan a pleasant event. These data are consistent with Silk et al's (2006) study of high risk youth, and Yap et al.'s (2008) examination of depressive symptoms in a community sample. The current study clarifies that aberrant patterns of positive affective functioning predate the development of depressive symptoms among families of high risk youth, and thus reflect features of a risk profile that may be targeted by prevention or early intervention efforts. Also, these data warrant a future longitudinal study to determine whether or not these patterns causally contribute to depression.

With regard to negative affect in a positive context, the current study supported disruptions at the individual level only among mothers, but not among high risk youth. In fact, the findings for increased negative affective behavior among mothers was quite strong with all behaviors (negative affect, dominance, conflict, withdrawal) significantly elevated, relative to low risk mothers. Moreover, there was evidence for transactional negative escalation in the context of positivity. Together these findings could suggest that maternal negativity is precipitating a transactional escalation of negative affect. However, it is important to note that a more micro-analytic approach (e.g., using a coding system that assesses behavior on a moment-to-moment time scale and highlights contingencies of behaviors on immediately preceding behaviors) may be necessary to disentangle interactions at this level. In fact, two recent reports from a non-clinical community sample employed a micro-coding system to look at maternal responses to adolescent negative affective behaviors. These studies showed that mothers of youth with more depressive symptoms tend to dampen positive experiences of their offspring (2008), and that offspring of mothers who respond negatively to their negative affective behaviors are more likely to develop depression (Schwartz, et al., 2011). Future work may further inform our understanding of these processes by using such micro-analytic systems to observe both maternal responses to adolescent behavior as well as adolescent responses to maternal behavior.

Taken together, these data suggest broadly that when there is a contextual opportunity for a positive experience, or to take a break from stress and recharge, mothers of high risk youth continue to engage in negative affective behaviors, and both high risk youth and their mothers transactionally reciprocate and escalate negative affect. This is important given the functional role of positive affect in building important resources for coping with future stress and negative affect (Fredrickson & Cohn, 2008). Over time, a failure to capitalize on positive experiences may lead to a lack of coping resources. Moreover, this possible socialization of positive affective behavior is consistent with data among adults demonstrating associations between depressive symptoms and tendencies toward dampening and failing to positively ruminate (or savor) on positive experiences (Bryant, 2003; Feldman, Joormann, & Johnson, 2008) . These data point to the possibility that at least some of these individual tendencies may be socialized in the home among high risk youth.

Finally, we examined affective functioning among this population in terms of changing contexts. There was support for group differences in the tendency to reduce negative affective behaviors when transitioning from a conflictual to a positive context. Specifically, mothers of high risk youth failed to show reductions in withdrawal behaviors, relative to low risk mothers; while high risk youth failed to show reductions in conflict and negative affect, relative to low risk youth. There was no support for group differences in activating positive affect when shifting between contexts, though this is likely due to the fact that positive affect was low across contexts for high risk youth, and high across contexts for low risk youth. Moreover, transactional processes were similar across contexts.

These data may be interpreted through the lens of several relevant theories. For example, this pattern may reflect a general reduced sensitivity to changing contexts (consistent with Emotion Context Insensitivity) and/or an inflexible pattern of affective functioning marked by a tendency to fail to deactivate negative affect and activate positive affect behaviors when contextual opportunities for positivity arise (consistent with Emotion Inertia Theory). Another possible interpretation is that mothers’ high displays of negative affect and the transactional escalation of negative affect is creating a negative context, despite the experimental scaffolding towards creating a positive context, such that these patterns of affective functioning reflect a failure to create (or engage in) a positive context. All of these interpretations converge to support the importance of examining affective functioning across contexts. These data reveal that it is not simply high negative affect that characterizes youth at high risk for depression and their mothers. Rather, there seems to be a failure to individually or mutually regulate negative affect in a way that is responsive to contextual demands and opportunities. Future work may consider counterbalancing context to gain a deeper understanding of these issues. That is, if youth show greater flexibility and change in affective behaviors when transitioning from a positive to a negative context, relative to when they are transitioning from a negative to positive context, it may suggest not a reduced sensitivity to context, but rather a tendency for the inertia of negative affective states to reduce the ability to respond to contextual opportunities for positivity.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the current study. First, cross sectional data do not allow for interpretation of how these patterns of affective functioning causally contribute to depressive symptoms. However, our examination of high risk youth prior to the development of symptoms offer an important window into familial functioning that ultimately may inform prevention and early intervention. Although outside of the scope of the current paper, we are currently following these youth longitudinally to determine how findings from the present study predict the development of symptoms in adolescence. A second limitation is our focus on mothers to the exclusion of fathers, family members, or other caretakers. Although mother-adolescent interactions are deemed particularly important, emerging research confirms the importance of father-adolescent relationships and affective functioning in the development of depressive symptoms (Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007; Sheeber, Johnston et al., 2009). Moreover, siblings and other individuals in the home may also contribute to the overall affective climate. Third, the observed contexts were fixed rather than counterbalanced, which limits our ability to determine whether findings represent a specific difficulty transitioning from a negative to positive context, or a general difficulty with affective sensitivity or reactivity to all contexts. Finally, although our focus on observational data, including contextual and transactional processes, was a strength of the current study, the evaluation of a greater number of discrete emotions, additional methods for assessing affect (e.g. self report), and moment-to-moment transactional exchanges with more micro-level coding systems may further complement our understanding of these processes. It is important to note, however, that this macro-analytic system (IDCS) converged substantially with key variables of affect coded by a micro-analytic system (Julien, et al., 1989), and that macro approaches may help to identify broad patterns that can be obscured by analyzing small units of behavior. Moreover, macro-analytic approaches may be quite suitable for informing prevention or early interventions that aim to target a broad pattern of functioning. For example, identifying which member of a dyad initiates a negative transactional cycle may be less important than the focus on altering the cycle through one or both members of the dyad.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

This study revealed that youth at high familial risk for depression and their mothers show unique deficits in positive affective functioning that are pervasive across contexts, and occur as both individual and transactional processes. Moreover, prior data among high risk youth and mothers did not provide evidence for deficits in negative affective functioning in the context of conflict (Dietz, et al., 2008). The current study replicated and extended these findings by demonstrating heightened negative affect was observed only in certain contexts (e.g. increased negativity in a positive context) and at the transactional level (heightened negative escalation in negative and positive contexts). These findings carry implications for identifying potential prevention and early intervention targets. For example, family therapy frequently focuses on reducing conflict in families of depressed youth, but if processes of positive affect and affective flexibility are particularly disrupted among high risk populations, it may be helpful to develop approaches targeting these processes. Capitalizing on positive contexts and learning skills for transitioning out of negative affective states may represent skills that are currently underdeveloped in family treatments. Also, targeting positive affect systems could be a helpful strategy, particularly given substantial literature in recent years pointing to the centrality of positive affective functioning to the pathophysiology and clinical course of depression—and particularly during this maturational period of adolescence (e.g., Davey, et al., 2008; Forbes & Dahl, 2005). Additionally, teaching parents how to not only effectively manage their own affect, but also to model and socialize healthy affective functioning may exert a significant influence on the course of early adolescents at high risk for depression during a vulnerable period of development.

References

- Beardslee WR, Keller MB, Lavori PW, Staley JE. The impact of parental affective disorder on depression in offspring: A longitudinal follow-up in a non-referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(4):723–730. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(11):1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. Guilford Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Meyer B. Lack of positive experiences and positive expectancies mediate the relationship between BAS responsiveness and depression. Cognition & Emotion. 2002;16(4):549–564. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Bridge JA, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, et al. Psychosocial functioning in youths at high risk to develop Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):839–846. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128787.88201.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB. Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. Journal of Mental Health (UK) 2003;12(2):175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in Major Depressive Disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(4):676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropley M, MacLeod AK. Dysphoria, attributional reasoning and future event probability. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2003;10(4):220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Davey CG, Yucel M, Allen NB. The emergence of depression in adolescence: Development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Silk JS, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, et al. Mother-child interactions in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):574–582. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman GC, Joormann J, Johnson SL. Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(4):507–525. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Healy BT, Goldstein S, Guthertz M. Behavior-state matching and synchrony in mother-infant interactions of non-depressed versus depressed dyads. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) John Wiley & Sons Inc; US; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Montemayor R, Eberly M, Torquati J. Unraveling the ties that bind: Affective expression and perceived conflict in parent-adolescent interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10(4):495–509. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE. Neural systems of positive affect: Relevance to understanding child and adolescent depression? Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(3):827–850. doi: 10.1017/S095457940505039X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Shaw DS, Dahl RE. Alterations in reward-related decision making in boys with recent and future depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA. Positive Emotions. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frye AA, Garber J. The relations among maternal depression, maternal criticism, and adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-0929-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shomaker LB. Patterns of interaction in adolescent romantic relationships: Distinct features and links to other close relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(6):771–788. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hamilton JP, Cooney RE, Singh MK, Henry ML, Joormann J. Neural processing of reward and loss in girls at risk for Major Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton EB, Jones M, Hammen C. Maternal interaction style in affective disordered, physically ill, and normal women. Family Process. 1993;32(3):329–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1993.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart S, Field T, del Valle C, Pelaez-Nogueras M. Depressed mothers’ interactions with their one-year-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21(3):519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Heller AS, Johnstone T, Shackman AJ, Light SN, Peterson MJ, Kolden GG, et al. Reduced capacity to sustain positive emotion in major depression reflects diminished maintenance of fronto-striatal brain activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(52):22445–22450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition & Emotion. 2000;14:711–724. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington E, Clingempeel W. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2-3):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Granic I, Stoolmiller M, Snyder J. Rigidity in parent-child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):595–607. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047209.37650.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Biglan A, Sherman L, Arthur J, Friedman L, Osteen V. Home observations of family interactions of depressed women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(3):341–346. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen AM. Positive Affect. In: Dalgleish T, Power MJ, editors. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 1999. pp. 521–539. [Google Scholar]

- Julien D, Markman HJ, Lindahl KM. A comparison of a global and a microanalytic coding system: Implications for future trends in studying interactions. Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11(1):81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children- (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychological Science. 2010;21(7):984–991. doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Graf M. Pleasant activities and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;41:261–268. doi: 10.1037/h0035142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27(8):986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Ullman JB. The impact of maternal depression on adolescent adjustment: The role of expressed emotion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):935–944. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: Moodiness or mood disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):133–135. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Detweiler JB, Steward WT, Bedell BT. Affect and health-relevant cognition. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of Affect and Social Cognition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah: 2001. pp. 344–368. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz OS, Dudgeon P, Sheeber LB, Yap MBH, Simmons JG, Allen NB. Observed maternal responses to adolescent behaviour predict the onset of major depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49(5):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Allen NB, Leve C, Davis B, Wu Shortt J, Katz LF. Dynamics of affective experience and behavior in depressed adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(11):1419–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: Associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):144–154. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews J. Family support and conflict: Prospective relations to adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(4):333–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1025768504415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Hops H, Andrews J, Alpert T, Davis B. Interactional processes in families with depressed and non-depressed adolescents: Reinforcement of depressive behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(4):417–427. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Johnston C, Chen M, Leve C, Hops H, Davis B. Mothers’ and fathers’ attributions for adolescent behavior: An examination in families of depressed, subdiagnostic, and nondepressed youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(6):871–881. doi: 10.1037/a0016758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Steinhauer SR, Thase ME, Stenger V, Carter CS. Can't shake that feeling: Event-related fMRI assessment of sustained amygdala activity in response to emotional information in depressed individuals. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(9):693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Lane TL, Kovacs M. Maternal depression and child internalizing: The moderating role of child emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):116–126. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Skuban EM, Oland AA, Kovacs M. Emotion regulation strategies in offspring of childhood-onset depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Ryan ND, et al. Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological context. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):841–865. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Quirk SW, Sajatovic M. Subjective and expressive emotional responses in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;46:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Wisner KL. Diminished response to pleasant stimuli by depressed women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(3):488–493. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Williamson DE, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, et al. Parent-child bonding and family functioning in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(11):1387–1395. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronick EZ. Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):112–119. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(2):320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg M, Tronick EZ. The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(S2):53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Verdeli H, Pilowsky D. Families at high and low risk for depression: A 3-generation study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle S, Yap MB, Yucel M, Sheeber LB, Simmons JG, Pantelis C, et al. Maternal responses to adolescent positive affect are associated with adolescents’ reward neuroanatomy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(3):247–256. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MB, Allen NB, Ladouceur CD. Maternal socialization of positive affect: The impact of invalidation on adolescent emotion regulation and depressive symptomatology. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MB, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Using an emotion regulation framework to understand the role of temperament and family processes in risk for adolescent depressive disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(2):180–196. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]