Abstract

Objectives

This study sought to derive and validate outcome-driven thresholds of central blood pressure (CBP) for diagnosing hypertension.

Background

Current guidelines for managing patients with hypertension mainly rely on blood pressure (BP) measured at brachial arteries (cuff BP). However, BP measured at the central aorta (central BP [CBP]) may be a better prognostic factor for predicting future cardiovascular events than cuff BP.

Methods

In a derivation cohort (1,272 individuals and a median follow-up of 15 years), we determined diagnostic thresholds for CBP by using current guideline-endorsed cutoffs for cuff BP with a bootstrapping (resampling by drawing randomly with replacement) and an approximation method. To evaluate the discriminatory power in predicting cardiovascular outcomes, the derived thresholds were tested in a validation cohort (2,501 individuals with median follow-up of 10 years).

Results

The 2 analyses yielded similar diagnostic thresholds for CBP. After rounding, systolic/diastolic threshold was 110/80 mm Hg for optimal BP and 130/90 mm Hg for hypertension. Compared with optimal BP, the risk of cardiovascular mortality increased significantly in subjects with hypertension (hazard ratio: 3.08, 95% confidence interval: 1.05 to 9.05). Of the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, incorporation of a dichotomous variable by defining hypertension as CBP ≥130/90 mm Hg was associated with the largest contribution to the predictive power.

Conclusions

CBP of 130/90 mm Hg was determined to be the cutoff limit for normality and was characterized by a greater discriminatory power for long-term events in our validation cohort. This report represents an important step toward the application of the CBP concept in clinical practice.

Keywords: central blood pressure, diagnostic thresholds, high blood pressure, hypertension

High blood pressure (BP) is one of the leading causes of global cardiovascular disease burden (1). Although BP is continuously distributed, and its relation to cardiovascular risk has been suggested to be continuous (2), clinicians rely on a diagnostic reference range to classify patients as normotensive or hypertensive. Conventional BP is measured by auscultation of the Korotkoff sounds or by automatic BP monitors (cuff BP), and a cutoff of 140/90 mm Hg has been used to diagnose high BP (3–5). With the recent evolution of evidence-based practice, ambulatory BP, which provides a better prognostic value, has been suggested as the reference standard for the management of hypertension (6).

Nevertheless, both ambulatory BP and conventional cuff BP are measured at brachial arteries, and BP amplification from the central aorta to peripheral arteries is well known to vary substantially among individuals and to cause conceivable discrepancies between central blood pressure (CBP) and cuff BP readings (7–12). Currently, noninvasive CBP can be obtained with either tonometry-based (9,13–15) or cuff-based techniques (16–18). Growing evidence (19) suggests that there are major discrepancies in CBP among people with similar peripheral BP levels (20,21), central BP may be more relevant than peripheral BP in predicting target organ damage and cardiovascular outcomes (22–24), central and peripheral BP may respond differently to antihypertensive medication in randomized controlled trials (25,26), and end-organ changes after antihypertensive medication are more strongly related to CBP than peripheral BP (27–29). We have previously suggested that CBP and ambulatory BP may have similar abilities to predict future outcomes (30). Because CBP as a reference standard may further improve current hypertension management, it is important for clinicians to utilize CBP values to classify patients with respect to their hypertension. However, threshold values of CBP have never been investigated in longitudinal event-based studies.

We derived an operational threshold for CBP based on an outcome-driven approach (31,32) and validated this threshold in another, independent cohort to examine its discriminatory ability for long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods

Study population

We performed the present analysis using individuals from 2 independently and prospectively recruited cohorts in Taiwan that were followed longitudinally. We have previously reported the relationship between CBP and cardiovascular mortality (23), and the participants of that study served as a derivation cohort from which the diagnostic thresholds were generated. Subsequently, the discriminatory ability of these thresholds for cardiovascular mortality was tested in a validation cohort. Details of the recruitment process and study protocols for the derivation and validation cohorts have been reported elsewhere (23,33–35) and are summarized in Table 1. All participants gave informed consent before enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals in the Derivation and Validation Cohorts

| Derivation Cohort (n = 1,272) |

Validation Cohort (n = 2,501) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 52.3 ± 12.8 | 53.6 ± 12.0 | 0.0027 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.7 ± 3.6 | 24.2 ± 3.2 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 198.1 ± 37.5 | 192.3 ± 39.1 | <0.0001 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 123.1 ± 34.3 | 122.0 ± 37.3 | 0.3927 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 50.9 ± 13.1 | 47.7 ± 16.8 | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73.6 ± 9.9 | 73.1 ± 10.2 | 0.1620 |

| Cuff SBP, mm Hg | 139.2 ± 23.6 | 122.4 ± 17.0 | <0.0001 |

| Cuff DBP, mm Hg | 88 ± 14.6 | 68.2 ± 10.2 | <0.0001 |

| Cuff PP, mm Hg | 51.2 ± 16.6 | 54.2 ± 12.2 | <0.0001 |

| Central SBP, mm Hg | 127.6 ± 23.7 | 111.8 ± 16.1 | <0.0001 |

| Central DBP, mm Hg | 86.3 ± 14.2 | 70.2 ± 10.3 | <0.0001 |

| Central PP, mm Hg | 41.3 ± 15.7 | 41.5 ± 11.0 | 0.6560 |

| Male | 53 | 45 | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 57 | 69 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | 24 | 24 | 0.517 |

| Optimal BP | 18 | 46 | <0.0001 |

| Prehypertension | 30 | 38 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 52 | 16 | <0.0001 |

Values are mean ± SD or %.

BP = blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; MBP = mean blood pressure; PP = pulse pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Derivation cohort

The derivation cohort for generating diagnostic thresholds included 1,272 normotensive and untreated hypertensive (systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≥90 mm Hg without any previous antihypertensive medication) Taiwanese participants (674 men, age 30 to 79 years) from a previous community-based survey conducted in 1992 to 1993 (36).

Validation cohort

Performance of the derived thresholds was determined in the validation cohort from CVDFACTS (the Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Two-Township Study), a community-based follow-up study focusing on risk-factor evaluation and cardiovascular disease development in Taiwan (34,35). Of the participants in CVDFACTS, a total of 3,386 individuals had undergone CBP measurements during their cycle 4 examination (1997 to 1999). From that group, we excluded 617 participants who were treated with antihypertensive drugs, 268 subjects with cardiovascular diseases or stroke history. Thus, data on the 2,501 individuals of the validation cohort were utilized in the present analyses.

Follow-up

By linking our database with the National Death Registry, we retrieved the dates and causes of death of all participants in the derivation and validation cohorts. Individuals that did not appear in the National Death Registry on December 31, 2007, were considered to be survivors. The median follow-up durations of the derivation and validation cohorts were 15 and 10 years, respectively.

BP measurement

Three or more sets of peripheral BP measurements (cuff BP) were obtained from the right arm, with ≥5 min between readings; measurements were made only after each person was seated for ≥5 min. Cuff BP, which was measured manually by experienced clinicians using a mercury sphygmomanometer and standard-sized cuffs, is reported as the average of the last 2 consecutive measurements.

In the derivation cohort, right common carotid artery pressure waveforms were calibrated with brachial mean blood pressure and DBP to obtain the carotid BP (13). The carotid artery pressure waveforms, registered non-invasively with a tonometer (22,36), have been demonstrated to closely resemble central aortic pressure waveforms (13,37,38). In the validation cohort, CBP was obtained with a SphygmoCor device (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) using radial arterial pressure waveforms and a validated generalized transfer function, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (39). Radial arterial pressure waveforms, obtained by applanation tonometry using a solid-state high-fidelity external Millar transducer, were calibrated with cuff SBP and DBP values, and then mathematically transformed by the validated transfer function (39) into corresponding central aortic pressure waveforms. Cuff and central pulse pressures (PPs) were calculated as: (SBP – DBP).

Other measurements

Early in the morning after an overnight fast, serum and plasma samples were drawn for glucose, lipids, and other biochemical measurements from patients in a sitting position. Dyslipidemia was defined according to “The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III)” (40). A classification of diabetes mellitus was indicated for participants with a fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or who were taking antidiabetic medication (41). In both cohorts, individuals undergoing BP measurements also completed a questionnaire-based interview containing items on demography, lifestyle, self-reported health conditions, medication history, and family history of disease.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as percent or mean ± SD. Student t test and chi-square test were used for between-group comparisons when appropriate

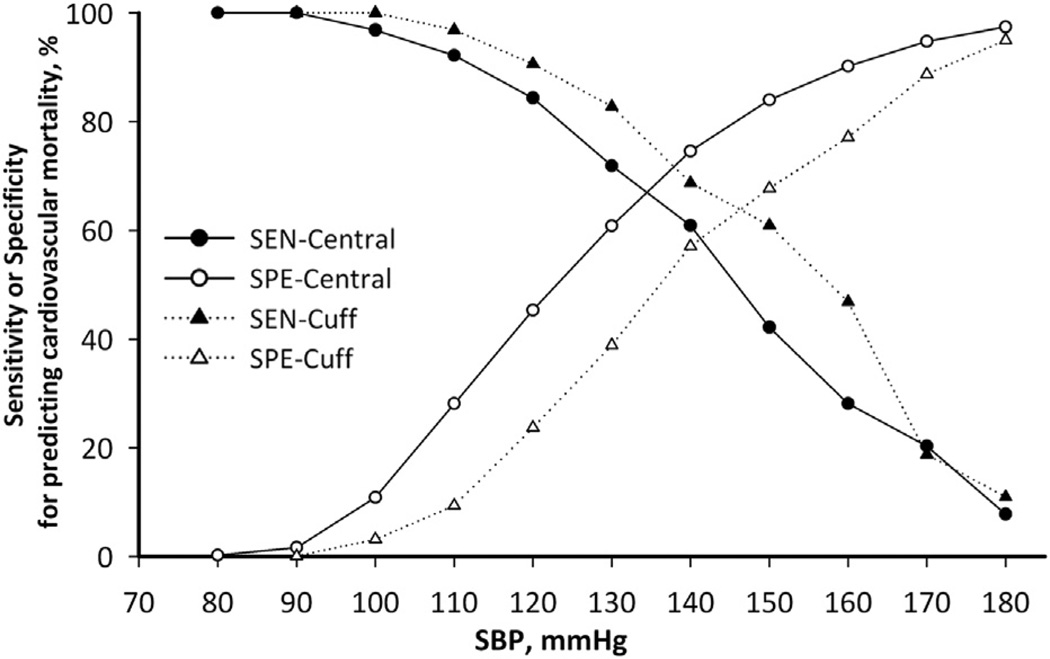

We obtained diagnostic thresholds and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CBP similar to a previous study deriving cutoffs for ambulatory BP and conventionally measured home BP (31,42). First, we identified the participants in the derivation cohort with a cuff BP that coincided with thresholds proposed by international guidelines (3–5) and calculated the corresponding cardiovascular mortalities (Table 2). Second, we used the bootstrap method for each cutoff by randomly selecting CBP levels 1,000 times from those of the corresponding identified participants. Third, we obtained the mean and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles from the re-sampling distribution to serve as the diagnostic thresholds of CBP with 95% CIs. Alternatively, we estimated the sensitivity and specificity of cuff SBP cutoff limits for predicting cardiovascular mortality (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

CBP Levels and Cardiovascular Mortalities With Different Cuff SBP and DBP Cutoffs Based on Conventional Criteria in the Derivation Cohort

| Hypertension Staging | Category | Diagnostic Thresholds for Cuff BP, mm Hg |

Cardiovascular Mortalities, % | Corresponding CBP Levels, mm Hg (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal–pre-hypertension | SBP | 120 | 2.7 | 112.80 (111.15–113.61) |

| DBP | 80 | 4 | 80.92 (79.60–82.22) | |

| Prehypertension–hypertension | SBP | 140 | 4.3 | 132.43 (130.89–133.88) |

| DBP | 90 | 5 | 90.98 (89.93–91.96) |

The cutoff criteria are based on international standards (3–5). Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from the bootstrap distribution of 1,000 random samples with replacement of CBP levels for participants in the derivation cohort.

CBP = central blood pressure;

other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Figure 1. The Sensitivity and Specificity of Cuff SBP and Central SBP for Predicting Cardiovascular Mortality in the Derivation Cohort.

With increasing systolic blood pressure (SBP) cutoff values, specificity (SPE) improved at the expense of decreasing sensitivity (SEN). Reasonable cutoff limits for central SBP can then be determined by approximating based on the sensitivity or specificity of the guideline-endorsed cuff SBP cutoff points as demonstrated in Table 3. cuff BP = peripheral blood pressure.

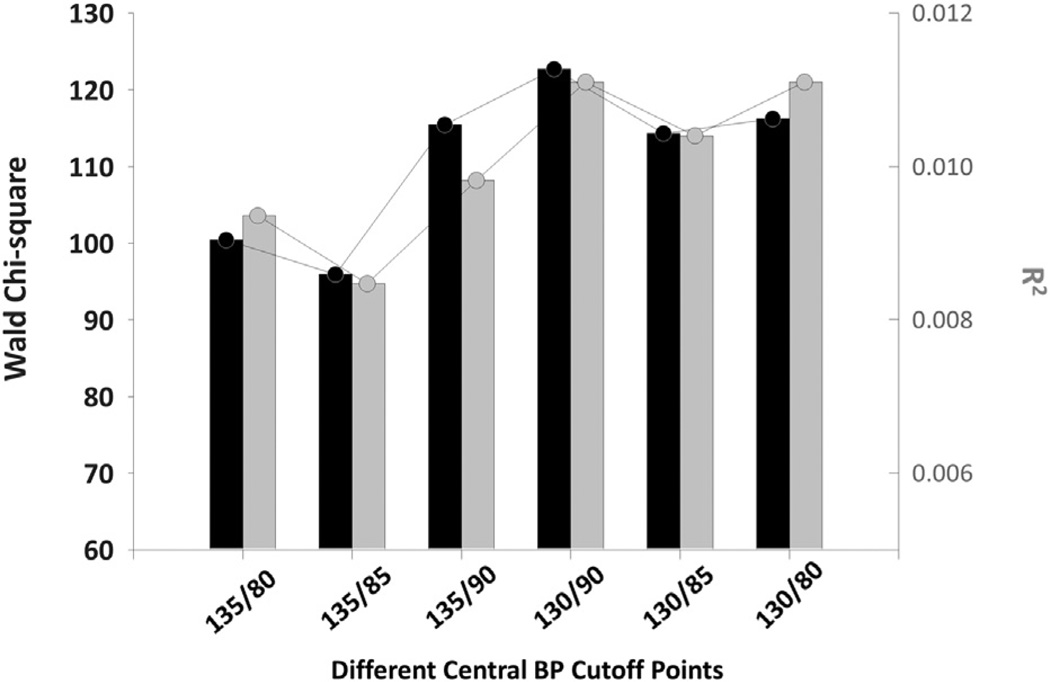

In addition, to conform with current guideline-endorsed management of arterial hypertension (3–5) based on cuff BP, we calculated the sensitivity and specificity of each cutoff point of central and cuff SBP in 10-mm Hg increments from 80 to 180 mm Hg for cardiovascular mortality. Considering that the sensitivity of cuff BP was higher than its specificity in predicting cardiovascular mortalities (Table 3), we then linked the points of central/cuff SBP and sensitivity/specificity to find the optimal cutoff point for central SBP that had equal sensitivity and approximate specificity (Fig. 1, Table 3). Furthermore, we used the Wald chi-square analysis from the Cox proportional hazard model to compare the discrimination among varied cutoff points for central SBP for cardiovascular mortality (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Determining Central SBP Cutoff Values Based on the Sensitivity and Specificity Associated With Cuff SBP Cutoff Values for Predicting Cardiovascular Mortality

| Cutoff, mm Hg | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuff SBP | 120 | 0.906 | 0.237 |

| Central SBP | 110.49 | 0.906 | 0.292 |

| Central SBP* | 110 | 0.922 | 0.281 |

| Cuff SBP | 140 | 0.688 | 0.603 |

| Central SBP | 132.6 | 0.688 | 0.648 |

| Central SBP* | 130 | 0.741 | 0.600 |

See Figure 1 for the approximation process.

Cutoff values from the above central SBP values after rounding.

Cuff SBP = peripheral systolic blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Figure 2. Performance of the CBP Diagnostic Thresholds in the Validation Cohort.

Incorporating the dichotomous variable of defined hypertension based on different central blood pressure (CBP) Levels (x-axis) and the resulting contribution (Wald Chi-square and model R2) to the predictive power of the Cox proportional hazards model are shown. A CBP cutoff limit of 130/90 mm Hg was associated with a higher Wald chi-square and model R2 than other thresholds.

A Cox proportional hazard model was constructed to evaluate the performance of the proposed diagnostic thresholds of CBP for predicting cardiovascular outcomes. Survival time was calculated from the date of the CBP measurement to the date of death or the end of follow-up (December 31, 2011). The estimated hazard ratio of the validation cohort was derived after accounting for sex, age, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, and serum total cholesterol level. As with other large cohort studies (2), BP was included first as a continuous function in the Cox regression model. Subsequently, on the basis of different CBP thresholds for defining hypertension, BP was incorporated into the model as a dichotomous variable to evaluate the discriminative ability of the respective cutoff limits. The discriminatory power of the differential models with and without blood pressure was evaluated with prognostic receiver-operating characteristic curves. The comparisons between the areas under the curve of the prognostic receiver-operating characteristic curves were made with a nonparametric method developed by DeLong et al. (43). We further used the integrated discrimination index, net reclassification index, and clinical net reclassification index to evaluate the reclassification effects of central/cuff BP for predicting future cardiovascular events (44). All statistics were calculated using SAS version 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

In the derivation and validation cohorts, data from a total of 1,272 (mean age, 52.3 years, 30 to 79 years) and 2,501 (mean age, 53.6 years, 32 to 90 years) participants, respectively, were used to evaluate diagnostic thresholds of CBP (Table 1). The mean differences between cuff and central SBP in the derivation and validation cohorts were 11.6 ± 17.5 mm Hg and 10.7 ± 4.8 mm Hg, and 9.9 ± 14.2 mm Hg and 12.7 ± 5.0 mm Hg between cuff and central PP, respectively (all p < 0.001). Compared with the derivation cohort, participants in the validation cohort were older, had lower cuff BP and CBP values, and had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia.

Derivation of diagnostic thresholds for CBP

Table 2 shows the risks of cardiovascular mortality in individuals with cuff SBP/DBP values according to the cutoff limits proposed by international guidelines. The risk was markedly increased with increasing cuff SBP and DBP values. Using a bootstrap procedure, we calculated the central SBP and DBP values that correspond to these cuff BP limits (Table 2).

Alternatively, as shown in Figure 1, the sensitivity and specificity for predicting cardiovascular mortality with cuff and central SBP were calculated. With the rise in SBP cutoffs, the specificity improved but sensitivity dropped. We then identified the respective sensitivity and specificity of the cuff BP limits proposed by the guidelines. By approximating the identified estimated sensitivity, we then derived the central SBP levels corresponding to these limits (Table 3).

On the basis of the analyses in Tables 2 and 3, we proposed the outcome-driven diagnostic thresholds for CBP after rounding the point estimates to an integer value ending in 0 or 5 (Table 4). Based on these easy-to-remember thresholds, categorization of BP distribution by CBP could be achieved.

Table 4.

Proposal for Outcome-Driven Diagnostic Thresholds for CBP Measurement

| Central SBP, mm Hg |

Central DBP, mm Hg |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal BP | <110 | and | <80 |

| Pre-hypertension | 110–129 | and/or | 80–89 |

| Hypertension | ≥130 | and/or | ≥90 |

Hazard ratios for cardiovascular mortality stratified by the proposed CBP thresholds in the validation cohort

Cox proportional hazards modeling showed that central SBP and central PP (per 0mmHg) were significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality (1.149, 95% CI: 1.032 to 1.279 and 1.102, 95% CI: 1.027 to 1.182), total mortality (1.09, 95% CI: 1.031 to 1.152 and 1.065, 95% CI: 1.027 to 1.104), and stroke mortality (1.257, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.476 and 1.117, 95% CI: 1.003 to 1.243) in the validation cohort, respectively (all p < 0.01). By contrast, cuff SBP had significant association only with total mortality (1.061, 95% CI: 1.004 to 1.122) and stroke mortality (1.204, 95% CI: 1.025 to 1.415), whereas cuff PP was only significantly associated with total mortality (1.042, 95% CI :1.003 to 1.082).

In addition, compared with cuff BP, CBP had an additional contribution to the prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes across traditional cardiovascular risk factors demonstrated by improved incremental C-index and integrated discrimination index, and net reclassification index for cardiovascular and stroke mortality, respectively (Online Table 1).

Table 5 shows the hazard ratio for cardiovascular outcomes in different BP categories on the basis of the CBP criteria proposed in Table 4. In the entire validation cohort, the risk of developing cardiovascular outcomes was significantly higher in individuals with hypertension defined as a CBP value of ≥130/90 mm Hg than in those with optimal BP. The performance of conventional international standards (3–5) and the CBP criteria in subgroup analysis in the validation cohort is presented in the online supplementary tables (all p for interaction with age and sex >0.05) (Online Tables 2 to 4).

Table 5.

Hazard Ratios for Total, Cardiovascular, and Stroke Mortality in Relation to CBP at Entry in the Validation Cohort (n = 2,501)

| Total Death |

Cardiovascular Death |

Stroke Death |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoints | 185 (7.4) | 34 (1.36) | 18 (0.72) |

| Pre-hypertension vs. optimal BP | 1.31 (0.87–3.35) | 1.59 (0.57–4.43) | 1.93 (0.45–8.31) |

| Hypertension vs. optimal BP |

2.14 (1.36–3.35) | 3.08 (1.05–9.05) | 6.12 (1.43–26.21) |

Performance of the CBP diagnostic thresholds in the validation cohort

As shown in Figure 2, in a Cox proportional hazards model, a CBP value of 130/90 mm Hg was associated with a better discriminatory ability and was characterized by higher Wald chi-square and model R2 values than other diagnostic thresholds for defining hypertension.

Discussion

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to derive and validate the outcome-driven diagnostic thresholds of CBP for the diagnosis of hypertension. Building on a large consensus, current guidelines rely on cuff BP measurements made at a clinic or at home or on 24-h ambulatory BP measurements to categorize individuals with different levels of SBP and DBP; these categories are then used to predict the future cardiovascular risks of these individuals (3,5,45). However, all these criteria are based on noninvasive BP measurements of brachial arterial pulses, which are generated from cardiac contractions and then transmitted from the central aortic pulses, the origin of all arterial pulses. Physiologically, with its close proximity to vital organs and the better prognostic value (22–24,26,46), CBP should be the most relevant BP relating to vascular events. Cuff BP is not so much a surrogate, but a compromised measure that is recorded because of technical limitations. With accumulating evidence supporting the use of CBP for the management of hypertension (3,26) and the available techniques (9,13–18), deriving diagnostic thresholds of CBP that conform to previous guidelines and that are aligned with cuff BP is an important step. The other strength of our study is that in addition to threshold derivation through rigorous statistical methods, we also validated the discriminatory powers of the derived cutoff values in another event-based cohort with long-term follow-up. In the validation cohort, the CBP was measured with a technique (radial tonometry and the generalized transfer function of SphygmoCor) that is different from that used in the derivation cohort (carotid tonometry). The consistent results in the derivation and validation cohorts and the comparable prognostic performances across different age and sex subgroups (all p for interaction >0.05) (Online Tables 3 and 4) suggest that our proposed thresholds (Table 4) are both reliable and valid.

Although we rigorously derived and validated the diagnostic thresholds for CBP measurements for the diagnosis of hypertension in agreement with current practice, caution should still be exercised for the following reasons. The relationship between BP and vascular mortality is continuous throughout middle and older age, but individuals with BP values that are lower than the threshold of current guidelines for hypertension management are not guaranteed to be free from cardiovascular risk (2). A recent systematic review suggested that antihypertensive drugs that are used to treat stage I hypertension have not been shown to reduce mortality or morbidity in randomized controlled trials, and this may again challenge the legitimacy of these guideline-endorsed thresholds (47). These observations may not be valid for ambulatory BP or for CBP, and more studies should be conducted to clarify these issues. However, in our validation cohort, we did observe the best discriminatory power for these particular CBP thresholds (i.e., 130/90 mm Hg) for predicting cardiovascular mortality (Fig. 2).

Sharman et al. (48) demonstrated that wide variations in the difference between cuff BP and CBP values can occur among patients with a similar cuff BP. The magnitude of variation is similar between healthy and diseased individuals, which suggests that CBP measurements may further improve risk stratification. In this regard, although CBP and cuff BP values are correlated closely with each other, it may be inappropriate to directly assume from such a correlation that cuff BP is a surrogate for CBP. Instead, by incorporating the CBP criteria into clinical practice, the possibility of an incremental clinical benefit in the management of hypertension could be ascertained.

Age- and sex-specific reference values for CBP have been provided in the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (20). Both cuff BP and CBP values increase with age, and a possible, but not user-friendly, clinical application could be the use of the reference values stratified by age and sex. However, in current international guidelines, the classification of cuff BP values disregards age, sex, and other cardiovascular risk factors. In our multivariate model, the results were consistent after accounting for these factors. In line with current clinical practice and considering the higher clinical events in the aged population, we now propose diagnostic thresholds of CBP without age and sex specification.

Diagnostic reference values of CBP had been used to define a special disease entity, spurious systolic hypertension, which is characterized by high cuff BP and low CBP (49). It has been proposed to be a rather common phenomenon in young age (50). Investigating a population of 750 individuals (352 men and 398 women) age 26 to 31 years, Hulsen et al. (49) suggested that participants with this condition have cardiovascular risk profiles comparable to normotensive individuals. They used the 90th percentile of central SBP distribution to obtain the cutoffs of CBP (124/90 mm Hg for men and 120/90 mm Hg for women). The reference values were, however, not representative of the general population and were obtained solely for their research purposes.

The distribution of central SBP was studied in a health check-up program in Japan in 10,756 participants (51). Using the late systolic upstroke of the radial pressure wave to represent central SBP with a HEM-9000AI monitor (Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan), they reported the reference values of optimal and normal central SBP categories as 112.6 ± 19.2 mm Hg and 129.2 ±14.9 mm Hg, respectively, similar to our results. That study probably represents the first effort to report the diagnostic threshold of CBP, but it was limited based on its study design, which consisted of a cross-sectional population rather than an event-based cohort. Therefore, the prognostic value of their proposed diagnostic thresholds could not be further evaluated.

Study limitations

Because our study population consisted of 2 Taiwanese populations, the generalizability of our study conclusions in terms of ethnicity is unclear. Nonetheless, our thresholds are consistent with the similar reference values proposed in the aforementioned Japanese population (51).

The techniques used to measure CBP in the derivation and validation cohorts were carotid tonometry and generalized transfer function with a SphygmoCor monitor, respectively, which are currently the 2 most popular CBP measurement methods (52). Whether the same reference values should be used for different methodologies is not clear. Problems have been encountered during the derivation process of diagnostic thresholds based on ambulatory BP and traditional home BP measurements (31,53). However, with similar results obtained with various techniques, adoption of universal criteria for CBP for the diagnosis and management of hypertension may become reasonable.

Neither cuff BP nor noninvasive CBP estimates are error free when compared with invasively measured counterparts (54). The relationship between BP and cardiovascular outcomes could be affected by measurement errors, which have been termed regression dilution bias or attenuation bias (55,56). Although the effect of the measurement error on the dilution of the prognostic value has been clearly delineated, correction may be neither necessary nor appropriate in most applications (57). In addition, the influence of measurement errors on the discriminatory power of diagnostic cutoff values remains an unresolved issue for both conventional cuff BP and CBP. These issues require further research for clarification.

Conclusions

We derived and validated the diagnostic thresholds of CBP based on 2 independent event-based cohorts with long-term follow-up. Consistent with the staging criteria of current international guidelines for the diagnosis of hypertension, we propose a CBP of 130/90 mm Hg to be used as cutoff limits for normality because these values were characterized by greater discriminatory power for cardiovascular mortality in our validation cohort. The present report represents an important step toward the application of the CBP concept to clinical risk factor profiles for CVD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 96-2314-B-010-035-MY3), an intramural grant from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital (grant V98C1-028), Grants-in-Aid from the Research Foundation of Cardiovascular Medicine (Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China), Research and Development contract NO1-AG-1-2118, the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan (NHRI-EX93-9225PP, NHRI-EX94-9225PP, PH-102-PP-19, NSC 5-2314-B-001-012-MY3, NSC 102-2314-B-400-001), and by the Department of Health in Taiwan (DOH80-27, DOH81-021, DOH8202-1027, DOH83-TD-015, and DOH84-TD-006). Dr. Chen reports that Microlife Co., Ltd., and National Yang-Ming University have signed a contract for transfer of the noninvasive central blood pressure estimating technique.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BP

blood pressure

- CBP

central blood pressure

- CI

confidence interval

- cuff BP

peripheral blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- PP

pulse pressure

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

APPENDIX

For supplemental tables, please see the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ. Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause T, Lovibond K, Caulfield M, McCormack T, Williams B. Guideline Development Group. Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;343:d4891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus RJ, Caulfield M, Williams B. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE hypertension guideline 2011: evidence based evolution. BMJ. 2012;344:e181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segers P, Mahieu D, Kips J, et al. Amplification of the pressure pulse in the upper limb in healthy, middle-aged men and women. Hypertension. 2009;54:414–420. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly RP, Gibbs HH, O’Rourke MF, et al. Nitroglycerin has more favourable effects on left ventricular afterload than apparent from measurement of pressure in a peripheral artery. Eur Heart J. 1990;11:138–144. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takazawa K, Tanaka N, Takeda K, Kurosu F, Ibukiyama C. Under-estimation of vasodilator effects of nitroglycerin by upper limb blood pressure. Hypertension. 1995;26:520–523. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avolio AP, Van Bortel LM, Boutouyrie P, et al. Role of pulse pressure amplification in arterial hypertension. Experts’ opinion and review of the data. Hypertension. 2009;54:375–383. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benetos A, Thomas F, Joly L, et al. Pulse pressure amplification a mechanical biomarker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C. McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretic, Experimental and Clinical Principles. 6 edition. London, UK: Arnold; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benetos A, Tsoucaris-Kupfer D, Favereau X, Corcos T, Safar M. Carotid artery tonometry: an accurate non-invasive method for central aortic pulse pressure evaluation. J Hypertens. 1991;9(Suppl 6):S144–S145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karamanoglu M, O’Rourke MF, Avolio AP, Kelly RP. An analysis of the relationship between central aortic and peripheral upper limb pressure waves in man. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:160–167. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams B, Lacy PS, Yan P, Hwee CN, Liang C, Ting CM. Development and validation of a novel method to derive central aortic systolic pressure from the radial pressure waveform using an N-point moving average method. J Am Cardiol. 2011;57:951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millasseau SC, Guigui FG, Kelly RP, et al. Noninvasive assessment of the digital volume pulse. Comparison with the peripheral pressure pulse. Hypertension. 2000;36:952–956. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng HM, Wang KL, Chen YH, et al. Estimation of central systolic blood pressure using an oscillometric blood pressure monitor. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:592–599. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber T, Wassertheurer S, Rammer M, et al. Validation of a brachial cuff-based method for estimating central systolic blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011;58:825–832. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.176313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharman JE, Laurent S. Central blood pressure in the management of hypertension: soon reaching the goal? J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:405–411. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEniery CM, Yasmin, Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEniery CM, Yasmin, McDonnell B, et al. Central pressure: variability and impact of cardiovascular risk factors: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial II. Hypertension. 2008;51:1476–1482. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27:461–467. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283220ea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankowski P, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Czarnecka D, et al. Pulsatile but not steady component of blood pressure predicts cardiovascular events in coronary patients. Hypertension. 2008;51:848–855. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Luca N, Asmar RG, London GM, O’Rourke MF, Safar ME. Selective reduction of cardiac mass and central blood pressure on low-dose combination perindopril/indapamide in hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1623–1630. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000125448.28861.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006;113:1213–1225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto J, Imai Y, O’Rourke MF. Monitoring of antihypertensive therapy for reduction in left ventricular mass. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:1229–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kampus P, Serg M, Kals J, et al. Differential effects of nebivolol and metoprolol on central aortic pressure and left ventricular wall thickness. Hypertension. 2011;57:1122–1128. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boutouyrie P, Bussy C, Hayoz D, et al. Local pulse pressure and regression of arterial wall hypertrophy during long-term antihypertensive treatment. Circulation. 2000;101:2601–2606. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang CM, Wang KL, Cheng HM, et al. Central versus ambulatory blood pressure in the prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities. J Hypertens. 2011;29:454–459. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283424b4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kikuya M, Hansen TW, Thijs L, et al. Diagnostic thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring based on 10-year cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2007;115:2145–2152. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuji I, Imai Y, Nagai K, et al. Proposal of reference values for home blood pressure measurement: prognostic criteria based on a prospective observation of the general population in Ohasama, Japan. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang KL, Cheng HM, Sung SH, et al. Wave reflection and arterial stiffness in the prediction of 15-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities: a community-based study. Hypertension. 2010;55:799–805. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuang SY, Bai CH, Chen JR, et al. Common carotid end-diastolic velocity and intima-media thickness jointly predict ischemic stroke in Taiwan. Stroke. 2011;42:1338–1344. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chuang SY, Bai CH, Chen WH, Lien LM, Pan WH. Fibrinogen independently predicts the development of ischemic stroke in a Taiwanese population: CVDFACTS study. Stroke. 2009;40:1578–1584. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CH, Ting CT, Lin SJ, et al. Which arterial and cardiac parameters best predict left ventricular mass? Circulation. 1998;98:422–428. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly RP, Karamanoglu M, Gibbs H, Avolio AP, O’Rourke MF. Noninvasive carotid pressure wave registration as an indicator of ascending aortic pressure. J Vasc Med Biol. 1989;1:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CH, Ting CT, Nussbacher A, et al. Validation of carotid artery tonometry as a means of estimating augmentation index of ascending aortic pressure. Hypertension. 1996;27:168–175. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pauca AL, O’Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5–S20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niiranen TJ, Asayama K, Thijs L, et al. International Database of Home blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome Investigators. Outcome-driven thresholds for home blood pressure measurement: International Database on HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes. Hypertension. 2013;61:27–34. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kottke TE, Stroebel RJ, Hoffman RS. JNC 7—it’s more than high blood pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2573–2575. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, O’Rourke MF, Safar ME, Baou K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with central haemodynamics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1865–1871. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006742.pub2. CD006742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharman J, Stowasser M, Fassett R, Marwick T, Franklin S. Central blood pressure measurement may improve risk stratification. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:838–844. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hulsen HT, Nijdam ME, Bos WJ, et al. Spurious systolic hypertension in young adults; prevalence of high brachial systolic blood pressure and low central pressure and its determinants. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1027–1032. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226191.36558.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Rourke MF, Vlachopoulos C, Graham RM. Spurious systolic hypertension in youth. Vasc Med. 2000;5:141–145. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0000500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takase H, Dohi Y, Kimura G. Distribution of central blood pressure values estimated by Omron HEM-9000AI in the Japanese general population. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:50–57. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Rourke MF, Adji A. Noninvasive studies of central aortic pressure. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:8–20. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smulyan H, Safar ME. Blood pressure measurement: retrospective and prospective views. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:628–634. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spearman C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. By C. Spearman, 1904. Am J Psychol. 1987;100:441–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hughes MD. Regression dilution in the proportional hazards model. Biometrics. 1993;49:1056–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith GD, Phillips AN. Inflation in epidemiology:“ the proof and measurement of association between two things” revisited. BMJ. 1996;312:1659–1661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.