Abstract

Previous research has shown that both alcohol use and jealousy are related to negative relationship outcomes. Little work, however, has examined direct associations between alcohol use and jealousy. The current study aimed to build upon existing research examining alcohol use and jealousy. More specifically, findings from current jealousy literature indicate that jealousy is a multifaceted construct with both maladaptive and adaptive aspects. The current study examined the association between maladaptive and adaptive feelings of jealousy and alcohol-related problems in the context of drinking to cope. Given the relationship between coping motives and alcohol-related problems, our primary interest was in predicting alcohol-related problems, but alcohol consumption was also investigated. Undergraduate students at a large Northwestern university (N = 657) in the US participated in the study. They completed measures of jealousy, drinking to cope, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. Analyses examined associations between jealousy subscales, alcohol use, drinking to cope, and drinking problems. Results indicated that drinking to cope mediated the association between some, but not all, aspects of jealousy and problems with alcohol use. In particular, the more negative or maladaptive aspects of jealousy were related to drinking to cope and drinking problems, while the more adaptive aspects were not, suggesting a more complex view of jealousy than previously understood.

Keywords: Jealousy, Drinking Problems, Drinking to Cope, Relationships

1. Introduction

The current study builds on previous research regarding alcohol use and relationship problems. More specifically, some research has shown jealousy to be associated with drinking problems (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). However, limited consideration has been given to potential mechanisms underlying this association. Moreover, previous research has not examined different types of jealousy when considering this relationship. Thus, several questions arise that may have important theoretical and practical implications. Why is jealousy associated with alcohol-related problems? Might drinking to cope (with negative affect) mediate this relationship? Do the various dimensions of jealousy differentially predict problems associated with alcohol use and related problems? This research serves as an initial attempt to address these questions.

1.1 Alcohol Use and Relationships

Findings from the extant literature indicate that relationship problems and drinking often co-occur (Marshal, 2003). Research has established associations between problem drinking and a host of marital problems (e.g., conflict, infidelity, violence; see Orford, 1990, for a review). These associations have not only been found with married couples, but have also been observed with dating couples. Levitt and Cooper (2010) examined patterns of specific relationship elements on subsequent alcohol use. Results revealed that the presence of negative elements (e.g., feeling disconnected from one’s partner, feeling one’s partner had behaved negatively toward her) and the absence of positive elements (e.g., feeling connected to one’s partner, higher levels of intimacy) were related to increased alcohol use among women. Further, Fischer et al. (2005) found that heavy drinking episodes over a 10-day period were associated with lower positivity in interactions with romantic partners.

1.2 Jealousy in Relationships

For people in relationships, romantic jealousy may be associated with alcohol use and problems due to its emotional influence in response to a perceived relationship threat. Feelings of romantic jealousy often stem from a threat (either real or imagined) to the quality or existence of a relationship (Ben-Ze’ev, 2010), and these feelings can further contribute to relationship problems and increased negative interactions with partners (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). For example, when negative interactions occur in a relationship, partners may seek support from others outside of the relationship, which may in turn elicit feelings of jealousy in the other partner and further negative interactions.

In considering how and why jealousy might be associated with alcohol use and related alcohol problems, it may be helpful to consider jealousy in the context of relationships more broadly. Generally speaking, romantic jealousy is defined as an emotional reaction to a threat to a relationship with one’s partner (Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989). Typically, romantic jealousy involves a social triangle and occurs when a relationship partner perceives that another person (real or imaginary) poses a potential threat to their romantic relationship (Mathes, 1991; Parrott & Smith, 1993; Salovey & Rothman, 1991; White & Mullen, 1989). Jealousy can, consequently, be conceptualized as an emotion that serves to motivate behaviors (e.g., somatic, cognitive, and behavioral responses) that protect an individual’s relationship from alternatives mates (Harris & Darby, 2010; Salovey, 1991). It is important to note that jealousy is sometimes interpreted as a sign of caring and concern for the partner, and has been positively associated with romantic love. Similar to feelings of love, jealousy is an emotion that assumes there is a level of commitment within a relationship (i.e., jealous feelings would not be present if individuals had an indifferent attitude toward their partners or were not invested in their relationships; Pines, 1998). Thus, jealousy can be conceptualized as an emotional response that has both positive/adaptive elements (e.g., an implicit recognition of the importance/value of a relationship and/or partner) that can motivate behaviors to preserve a relationship. Conversely, jealousy also promotes negative/maladaptive actions (e.g., intrusive behaviors, harassment, domestic violence). For example, jealousy is frequently implicated as a factor in relationship dissolution and spousal abuse (Daly & Wilson, 1988; Harris, 2003).

Given the dynamic nature of romantic jealousy, several researchers have provided support for jealousy as a multidimensional construct. For example, research by Hupka, which included three factor-analytic studies involving 1,072 students (Hupka & Bachelor, 1979), found support for six dimensions of jealousy. First, threat to exclusivity refers to emotions that arise when one perceives his or her partner may be interested in leaving the committed relationship. Second, dependency refers to one person’s need for or reliance on his or her partner. Third, sexual possessiveness emphasizes the desire for one’s partner to only engage in sexual behaviors with him or her. Fourth, distrust refers to a suspicion that one’s partner may be intimately interested in another person. Fifth, envy or self-deprecation alludes to feelings of void when one sees another successful relationship. Finally, competition/vindictiveness refers to a feeling of malicious, spite, or bitterness as a function of perceiving a potential threat to one’s relationship. We suggest that these six aspects of jealousy could be conceptualized as falling into adaptive or maladaptive categories. Specifically, we suggest that the first three factors of jealousy (e.g., threats to exclusivity, dependency, sexual possessiveness) may not necessarily be unhealthy. For example, all relationships, including healthy ones, involve some degree of dependence on one’s partner. We also suggest that the latter three factors of jealousy (e.g., distrust, self-depreciation, and competiveness/ vindictiveness) may represent a ‘darker’ side. It is possible that these three factors of jealousy may be associated with unhealthy coping mechanisms such as drinking to cope. The current study investigates these six factors and evaluates the degree to which these different adaptive vs. maladaptive facets of jealousy are related to drinking to cope and problems with alcohol use.

1.3 Jealousy and Drinking

There is some support for the idea that jealousy is associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems (e.g., hangovers, alcohol-related physical sickness, and regret around one’s behaviors). For example, Foran and O’Leary (2008) examined two potential moderators of the association between alcohol problems and intimate partner violence (IPV) within a community sample of males. Specifically, they evaluated the moderating role of aggression control and jealousy as they related to alcohol problems and the perpetration of IPV. A three-way interaction was found between jealousy, anger control, and drinking problems, in predicting aggression. Further, jealousy versus anger control accounted for the majority of the variance in predicting partner aggression. In addition, Knox, Breed, and Zusman (2007) found that a significant proportion of men and women reported drinking in response to feeling jealous. This suggests that alcohol may be used as a coping mechanism for feelings of jealousy and suggests that drinking to cope may therefore mediate the association between jealousy and problem drinking.

1.4 Drinking to Cope

Given the strong association between drinking to cope and alcohol problems, and research showing a connection between feelings of jealousy and drinking problems, we expected to find empirical studies that examined drinking to cope and jealousy. However, we could not find any research to date that has examined the association between these constructs. While no previous research has specifically examined drinking to cope as a mediator of the association between jealousy and drinking problems, as noted, some research has shown jealousy to be associated with alcohol problems (Foran & O’Leary, 2008). Moreover, considerable research has demonstrated strong links between drinking to cope and drinking problems (e.g., Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engles, 2005; Lewis et al., 2008). For example, Park and Levenson (2002) found that when college students were asked whether they used alcohol to cope, 42.3% said yes. Additionally, when asked if they used alcohol to cope with stressors, 37.6% reported doing so. Neighbors et al. (2007) found that coping motives were more strongly associated with drinking problems than other motives, expectancies, social norms, gender, or fraternity/sorority memberships. Furthermore, coping motives were strongly associated with alcohol problems beyond the amount of alcohol consumed. Thus, a simultaneous examination of these three constructs – i.e., drinking to cope, jealousy, and alcohol problems – would not only bridge a gap in the literature but would also be warranted from a theoretical standpoint.

1.5 Present Study

Based on previous research suggesting associations between jealousy and alcohol problems and between coping and alcohol problems, the present study was designed to evaluate whether drinking to cope mediates associations between jealousy and drinking problems. Alcohol problems were of primary interest in this research given their strong connection with drinking to cope and previous associations with jealousy. Because we expect that jealousy should be associated with the “darker side” of coping behaviors, we expected that this model would be specific to alcohol problems rather than alcohol use per se. Thus, we hypothesized that the maladaptive aspects of jealousy (threats to exclusivity, dependency, sexual possessiveness) would be associated with both drinking to cope motives and drinking problems and that adaptive aspects of jealousy would not be. We also hypothesized that the association between maladaptive aspects of jealousy and drinking problems would be mediated by drinking to cope.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

The present research is a cross-sectional secondary analysis of follow-up data from a larger alcohol intervention study. Additional details regarding the intervention are available elsewhere (Neighbors et al., 2010). Incoming college freshman at a large Northwestern U.S. public university were invited to participate in a web-based survey as part of a larger social norms intervention study. Selection criteria included reporting one or more heavy drinking episodes in the previous month at baseline (4+/5+ drinks on an occasion for women/men) and minimum age of 18. The data being used in the current paper comes from the two-year follow-up assessment survey. This provided a sample of 657 (59.37% female) participants. Participants were an average of 20.18 (SD = 0.60) years of age at the time of the survey. Ethnicity of participants was 64.7% Caucasian, 24.4% Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.5% Hispanic/Latino(a), 1.2% Black/African American, and 4.5% Other.

2.2 Procedures

Participants involved in this study completed an initial 20-minute web-based screening assessment, a baseline assessment, and four additional 50-minute surveys at six-month intervals as part of a larger, Web-based normative feedback intervention study targeting college student drinking. The jealousy measure, the primary focus of this study, was added to the assessment battery at the final follow-up. The Institutional Review Board at the university where the research was conducted approved all aspects of the study.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Jealousy

Jealousy was measured using the Interpersonal Relationship Scale (IRS; Hupka & Rusch, 1979, 1989). The IRS is comprised of 27 items that assess six aspects of romantic jealousy. Items are answered on a six-point scale based on the level of agreement with each statement. Response options include a six-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6).Threat to exclusivity is assessed by seven items (e.g., “When my partner pays attention to other people, I feel lonely and left out”; α= .79). Dependency is assessed by four items (e.g., “I often feel I couldn't exist without him/her”; α = .84). Sexual possessiveness is assessed by three items (e.g., “It would bother me if my lover frequently had satisfying sexual relations with someone else”; α = .63). Distrust is assessed by three items (e.g., “When I am away from my mate for any length of time, I do not become suspicious of my mate's whereabouts” (reverse scored); α = .61). Envy/self-deprecation is assessed by seven items (e.g., “I often find myself idealizing persons or objects”; α = .85). Finally, competition/vindictiveness is assessed by three items (e.g., “I always try to 'even the score’”; α = .65).

2.3.1 Drinking to cope

Drinking to cope was assessed with the five-item coping subscale of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994), which contains reasons why people might be motivated to drink alcohol. Participants responded to items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never/Almost never; 2 = Some of the time; 3 = Half the time; 4 = Most of the time, and 5 = Almost always/Always). Example items include “To forget your worries,” “Because it helps you when you feel depressed or nervous,” and “To forget about your problems.” (α = .86).

2.3.2 Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff et al., 1999). Participants were asked “Consider a typical week during the last three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), do you drink on each day of a typical week?”). Participants provide estimates for the typical number of drinks they consume each day of the week. Responses are summed to reflect average number of drinks per week over the past thee months.

2.3.3 Alcohol-related problems

A modified version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed how often participants experienced 25 alcohol-related problems over the previous three months. The RAPI was modified to include two additional items (e.g., “drove after having two drinks” and “drove after having four drinks”). Participants responded to the statements using a five point scale (0 = never; 1 = 1 to 2 times; 2 = 3 to 5 times; 3 = 6 to 10 times; 4 = more than 10 times). Scores were calculated by summing the 25 items (α = .95).

2.4 Analyses

Our general aim was to examine associations between jealousy subscales, alcohol use, drinking to cope, and drinking problems. We did this by first examining zero-order correlations among all variables. Next, we conducted a regression analysis to evaluate unique associations between jealousy subscales and alcohol consumption. Then we conducted regression analysis to evaluate unique associations between jealousy and drinking problems. Finally, we used path analysis to evaluate unique associations between jealousy subscales and drinking to cope. This analysis also provided tests of indirect effects to evaluate drinking to cope as a mediator of associations between jealousy subscales and drinking problems.1

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive Results

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for jealousy, drinks per week, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems are presented in Table 1. Overall, drinks per week was not related to jealousy (see Table 1). Given the lack of an association between these two, we focused the remainder of our analyses on alcohol related-problems. Overall, jealousy tended to be positively associated with drinking to cope and alcohol-related problems. Specifically, five of the six jealousy subscales (all except sexual possessiveness) were significantly and positively correlated with drinking to cope, ranging in magnitude from .17 to .32. Four of the jealousy subscales were positively associated with drinking problems. In contrast to the other subscales, dependency was significantly and negatively correlated with drinking problems (r = −.13, p <.01). Sexual possessiveness was not associated with drinking problems. Finally, consistent with previous research, drinking to cope was significantly associated with drinking problems (r =.38, p < .001).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 98. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Threat to Exclusivity | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Envy | 0.62*** | -- | |||||||

| 3. Dependency | 0.57*** | 0.43*** | -- | ||||||

| 4. Sexual Possessiveness | 0.60*** | 0.26*** | 0.28*** | -- | |||||

| 5. Vindictiveness | 0.51*** | 0.54*** | 0.41*** | −0.20*** | -- | ||||

| 6. Distrust | −0.26*** | −0.01 | −0.22*** | 0.49*** | 0.01 | -- | |||

| 7. Drinking to Cope | 0.23*** | 0.32** | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.32*** | 0.17*** | -- | ||

| 8. Drinks per Week | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09* | 0.14*** | -- | |

| 9. Drinking Problems | 0.09* | 0.17*** | −0.13** | 0.03 | 0.25*** | 0.13** | 0.38*** | 0.40*** | -- |

| Mean | 3.10 | 2.57 | 2.32 | 4.17 | 2.43 | 2.90 | 1.78 | 9.80 | 5.73 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.19 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 1.29 | 0.78 | 10.05 | 10.07 |

Note. Numbers 1–6 in the table represent the six jealousy subscales

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05 N=657

3.2 Regression Analyses for Jealousy, Drinking, and Drinking Problems

To identify unique associations with problems, drinking problems were regressed on the jealousy subscales. Table 2 presents a regression analysis examining alcohol-related problems as a function of jealousy subscales. Overall, jealousy accounted for 8.6% of the variance in drinking problems, F (6,631) = 9.89, p < .001. Consistent with our hypotheses none of the adaptive aspects of jealousy were associated with drinking problems. Moreover, results indicated that two of the three maladaptive aspects of jealousy, vindictiveness (β = .218, t(637) = 4.57, p < .001) and distrust (β = .218, t(637) = 2.65, p < .01) were uniquely and directly associated with drinking problems.

Table 2.

Simultaneous Linear Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Alcohol-Related Problems

| Predictor | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Threats to Exclusivity | −0.86 | 0.669 | −0.085 |

| Envy | 0.674 | 0.472 | 0.075 |

| Dependence | 0.687 | 0.408 | 0.081 |

| Sexual Possessiveness | −0.026 | 0.420 | −0.003 |

| Vindictiveness | 1.979 | 0.433 | 0.218** |

| Distrust | 0.935 | 0.356 | 0.119* |

Note. N=657

p < .01

p < .05.

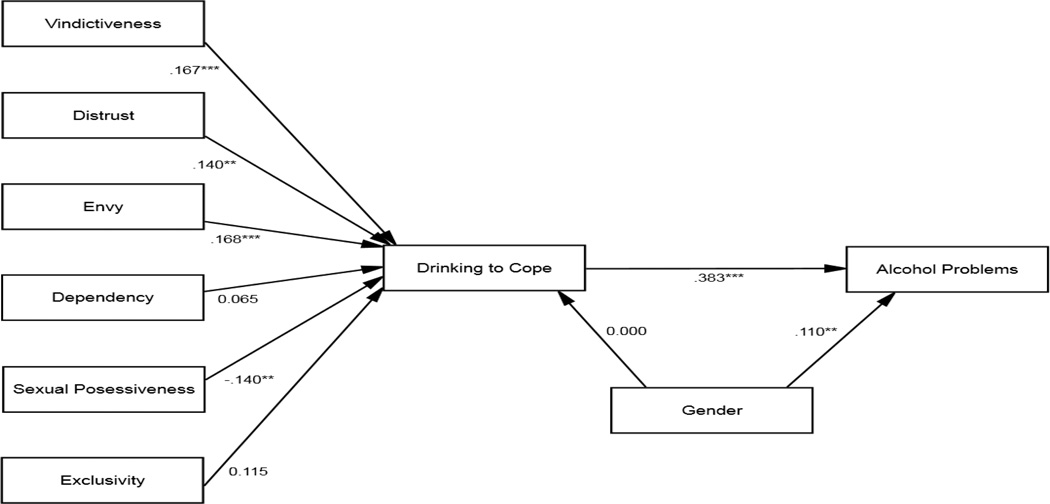

Next we examined associations between jealousy subscales and drinking to cope. We did this using path analysis using AMOS 20, which allowed us to also include the association between drinking to cope and alcohol problems in the same model. Results from analyses controlling for gender indicated that men experience more alcohol-related problems than women (β = .099, p < .01). However, including gender as a covariate with the jealousy subscales did not alter any of the paths, this was not presented in Figure 1 for the sake of clarity. Drinking outcomes exhibited significant positive skew. Bootstrapping methods were used to obtain robust standard errors that account for the non-normality of the data. Thus, the test statistics represent robust tests of significance of the individual paths. We examined unique associations between jealousy subscales and drinking to cope and indirect effects of jealousy subscales on drinking problems through drinking to cope. Figure 1 presents standardized coefficients for the resulting model. Correlations were specified among jealousy subscales but are not presented for the sake of clarity. Values were consistent with correlations in Table 1. All significance levels and directions were the same. Overall model fit was reasonable, χ2 (6) = 20.13, p = .003; NFI = .988; CFI = .991; RMSEA = .061 with a 90% CI of .033 and .091. Results examining unique associations between jealousy subscales and drinking to cope were relatively consistent with the zero-order correlations, with the exception that threat to exclusivity was marginally significant (p = .07). Envy (β = .168, p < .001), vindictiveness (β = .168, p < .001), and distrust (β = .141, p < .001) were uniquely and positively associated with drinking to cope. Moreover, sexual possessiveness (β = −.140, p < .01) was negatively associated with drinking to cope, whereas threat to exclusivity and dependency were not uniquely associated with drinking to cope.

Figure 1.

The association between jealousy and alcohol problems is mediated by drinking to cope. The estimates presented are standardized estimates. Correlations among jealousy subscales were specified but not included for clarity. Including gender as a covariate did not alter of the jealousy paths, this was not included for clarity. Values were consistent with correlations in Table 1. ** p<.01, *** p < .001.

Indirect effects were evaluated using MacKinnon’s ab products approach using Sobel’s test (Sobel, 1982). Mediation effects were evaluated for cases where both the a and b paths were significant (i.e., envy, vindictiveness, and distrust). Results revealed significant positive indirect effects for envy, Z = 3.42, p = .001, vindictiveness, Z = 3.31, p =.001, and distrust, Z = 3.36, p = .001.

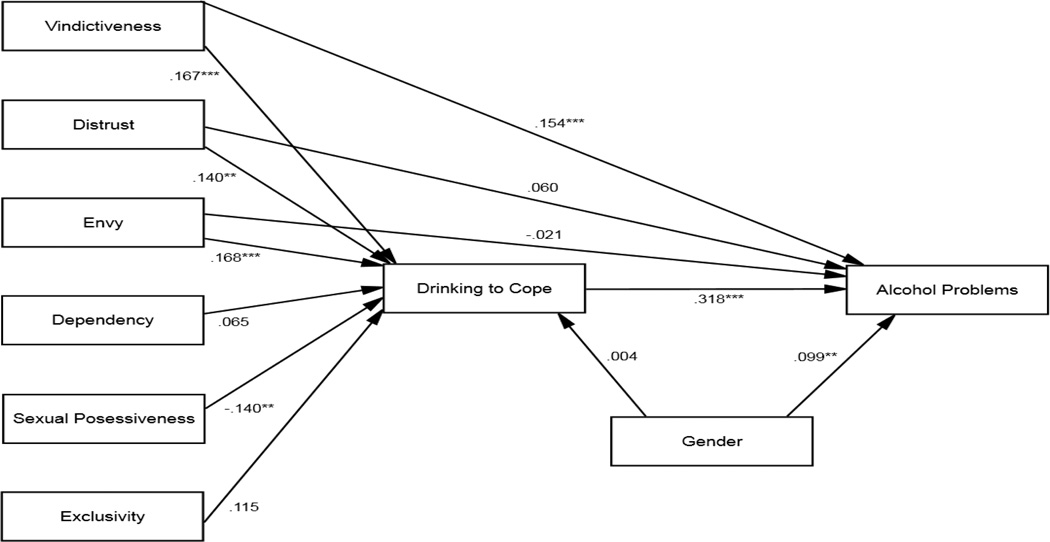

Although the hypothesized model fit the data reasonably well, we also examined a model with direct paths from envy, vindictiveness, and distrust to drinking problems. Thus, the model was re-estimated, exactly as before, but this time with the added direct paths. Figure 2 presents standardized coefficients for the resulting model. Again, correlations were specified among jealousy subscales but are not presented in Figure 2 for the sake of clarity. This second model demonstrated improved model fit, χ2(3)= 3.46, p = .33; NFI = .998; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .015 with a 90% CI of .000 and .070. Because this second model is nested within the initially hypothesized model, a chi-square difference test was performed to ascertain if there was a statistically significant difference between the two models. Results showed that this test was not significant, χ2 diff (3)= 16.67, p < .001.Thus, the second model was a significantly better fit than the hypothesized model and was retained.

Figure 2.

The association between jealousy and alcohol problems is mediated by drinking to cope. The estimates presented are standardized estimates. Correlations among jealousy subscales were specified but not included for clarity. Including gender as a covariate did not alter of the jealousy paths, this was not included for clarity. Values were consistent with correlations in Table 1. ** p<.01, *** p < .001.

4. Discussion

The present study examined associations between maladaptive and adaptive aspects of jealousy and drinking and evaluated whether drinking to cope mediated associations between the different aspects of jealousy and drinking problems. Overall, findings indicated that the maladaptive aspects of jealousy were positively associated with drinking to cope and alcohol related problems. Consistent with expectations, drinking to cope mediated the associations between all of the maladaptive jealousy subscales and problems associated with alcohol use. These findings suggest the possibility of a functional relationship between maladaptive jealousy and drinking problems For example, aspects of jealousy such as envy, vindictiveness, and distrust are likely to correspond with high levels of negative affect. The activation of negative affect may motivate individuals to drink, which, in turn, leads to greater alcohol-related problems.

In contrast to the above findings the adaptive aspects of jealousy, sexual possessiveness, dependency, and threats to exclusivity were not positively associated with drinking to cope and alcohol problems. In the path analysis, there was a significant negative indirect association between sexual possessiveness and drinking problems through drinking to cope and no significant indirect association between dependency, threats to exclusivity, and drinking problems through drinking to cope. Given that these three subscales are measuring more positive aspects of jealousy it makes sense that they would not be related to drinking to cope and subsequent problems with alcohol. For example, the sexual possessiveness subscale includes items such as, “It would bother me if my lover frequently had satisfying sexual relations with someone else.” Individuals not endorsing this item may have no meaningful commitment to the relationship and these feelings of “jealousy” may be considered adaptive or normative reactions in a committed exclusive relationship. Similarly, the dependence subscale includes items such as, “My lover is the motivating force in my life,” which could certainly be linked to feelings of commitment, satisfaction, and other positive aspects of a relationship. Finally, the threats to exclusivity subscale includes items such as, “When I see my lover kissing someone else, my stomach knots up.” This emotion, like those in the other two subscales, could be associated with more positive elements of jealousy. Each one of these subscales includes items that measure feelings and reactions that are associated with positive elements of a relationship, rather than negative.

Overall, these findings point to a more complex view of jealousy and provide support for the notion that jealousy is a multi-dimensional construct. Moreover, these findings suggest that only the relatively maladaptive facets of jealousy (envy, vindictiveness, and distrust) are associated with drinking to cope and negative drinking outcomes. In contrast, the relatively adaptive aspects of jealousy, that may promote healthy feelings in a relationship, do not appear to be connected to drinking to cope and negative drinking behaviors.

The findings with regard to alcohol consumption versus problems are also interesting and shed further light into how individuals are managing negative affect. As expected, little support was found for connections between jealousy, drinking to cope, and alcohol consumption. Rather, findings were primarily evident when predicting alcohol-related problems. Consistent with research indicating that negative affect is more strongly associated with problems rather than consumption (e.g., Kuntsche et al., 2008; Kuntsche et al., 2005; Park & Grant, 2005), our results suggest that feelings of jealousy were not associated with more alcohol use overall, but rather associated with alcohol-related consequences or problems as a function of drinking. This association suggests the possibility that in response to jealousy, students are engaging in heavy drinking episodes when drinking rather than spreading the same number of drinks over several days.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

This study represents a first step toward investigating the relations among jealousy, drinking to cope, and drinking. The generalizability and ultimate implications of the findings are limited by several factors. First and foremost, although study findings provide support for drinking to cope as mediators of (three aspects) of jealousy and alcohol-related problems, the study design is cross-sectional and cannot establish causality. Moreover, the path coefficients are relatively weak when predicting drinking to cope. Consequently, future research and study designs that are prospective/longitudinal will be important. Second, much of the extant literature on jealousy and alcohol focused on older, married couples. Future research should consider populations beyond undergraduates, including same-age non-college attending peers as well as older adults. In addition, evidence for mediation was observed for the three aspects of jealousy that had the lowest internal reliabilities. Future research could focus on improving the measurement of aspects of jealousy. Finally, participants came from a sample of heavy drinking students. Future research may benefit from an examination of jealousy models and drinking to cope among lighter drinkers as well.

4.2. Conclusion

Overall, the study advances our understanding of the association between jealousy and drinking in several respects. First, it evaluates a multi-dimensional conceptualization of jealousy, which allows for a more fine-grained investigation of jealousy itself and sheds new light on potentially healthy versus unhealthy jealous emotions. Second, this study investigates two aspects of drinking – alcohol-related consumption as well as alcohol-related problems – both of which had been found, in prior research, to be associated with jealousy. Findings are supportive of, at least when considering multi-dimensional conceptualizations, a relation between problems but not consumption, per se. Finally, mediation analyses provided preliminary support for drinking to cope as a mediator of the jealousy-problems association, with the greatest support for the aspects of jealousy (i.e., envy, vindictiveness, distrust) that could be characterized as being more maladaptive and reflecting negative affect. Ultimately, findings are suggestive of a functional relationship between the more negative, maladaptive aspects of jealousy, with each being associated with increased coping motives for drinking, and, in turn, with increased alcohol-related problems.

Highlights.

Findings provide support for jealousy as a multi-dimensional construct

Maladaptive jealousy is associated with problematic drinking among college students

Drinking to cope mediates the link between maladaptive jealousy and alcohol problems

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Ezekiel Hamor for his assistance with proofreading and editing this text.

This research was supported by the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington. This research was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA014576 and manuscript preparation was supported in part by R00AA017669.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

As the data comes from a larger alcohol prevention study, all analyses were also performed controlling for the intervention conditions. Results were not different when controlling for the intervention, and therefore, we report here on analyses without controlling for the intervention. Details regarding intervention effects are available elsewhere (Neighbors et al., 2010).

Contributors

Author 1 conducted the literature search and summary of previous research studies.

Authors 1, 2, 3, and 4 developed statistical analysis, and development of all drafts of the manuscript, including the final draft.

Conflict of Interest

All four authors have declared no conflict of interest.

NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Ben-Ze'ev A. Jealousy and romantic love. In: Hart SL, Legerstee M, editors. Handbook of jealousy: Theory, research, and multidisciplinary approaches. Wiley-Blackwell: 2010. pp. 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Wilson M. Evolutionary social psychology and family homicide. Science. 1988;242(4878):519–524. doi: 10.1126/science.3175672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland B, Lee J, McKnight A, Miller B. Binge drinking in the context of romantic relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1496–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Problem drinking, Jealousy, and anger control: Variables predicting physical aggression against a partner. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CR. A review of sex differences in sexual jealousy, including self-report data, psychophysiological responses, interpersonal violence, and morbid jealousy. Personality And Social Psychology Review. 2003;7(2):102–128. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0702_102-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CR, Darby RS. Jealousy in adulthood. In: Hart SL, Legerstee M, editors. Handbook of jealousy: Theory, research, and multidisciplinary approaches. Wiley-Blackwell: 2010. pp. 547–571. [Google Scholar]

- Hupka RB, Bachelor B. Validation of a scale to measure romantic jealousy. San Diego: Paper presented at the meeting of the Western Psychological Association; 1979. Apr, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hupka RB, Rusch PA. Interpersonal Relationship Scale. In: White GL, Mullen PE, editors. Jealousy: Theory, research, and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Knox D, Breed R, Zusman M. College men and jealousy. College Student Journal. 2007;41(2):494–498. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper M. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2008;69(3):388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Hove M, Whiteside U, Lee C, Kirkeby B, Oster-Aaland L, Neighbors C, Larimer M. Fitting in and feeling fine: conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For Better or for Worse? The Effects of Alcohol Use on Marital Functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(7):959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes EW. Dealing with romantic jealousy by finding a replacement relationship. Psychological Reports. 1991;69(2):535–538. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(6):898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J. Alcohol and the family: An international review of the literature with implications for research and practice. In: Kozlowski LT, Annis HM, Cappell HD, Glaser FB, Goodstadt MS, Israel Y, Vingilis ER, editors. Research advances in alcohol and drug problems. Vol. 10. New York, NY US: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 81–155. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott W, Smith RH. Distinguishing the experiences of envy and jealousy. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology. 1993;64(6):906–920. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SM, Wong PT. Multidimensional jealousy. Journal Of Social And Personal Relationships. 1989;6(2):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pines AM. A prospective study of personality and gender differences in romantic attraction. Personality And Individual Differences. 1998;25(1):147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch PA, Hupka RB. Development and validation of a scale to measure romantic jealousy. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Seattle, WA. 1979 [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P. The psychology of jealousy and envy. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Rothman AJ. Envy and jealousy: Self and society. In: Salovey P, editor. The psychology of jealousy and envy. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. Vol. 1982. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White GL, Mullen PE. Jealousy: Theory, research, and clinical strategies. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]