Abstract

Background

Civilian populations now comprise the majority of casualties in modern warfare, but effects of war exposure on alcohol disorders in the general population are largely unexplored. Accumulating literature indicates that adverse experiences early in life sensitize individuals to increased alcohol problems after adult stressful experiences. However, child and adult stressful experiences can be correlated, limiting interpretation. We examine risk for alcohol disorders among Israelis after the 2006 Lebanon War, a fateful event outside the control of civilian individuals and uncorrelated with childhood experiences. Further, we test whether those with a history of maltreatment are at greater risk for an alcohol use disorder after war exposure compared to those without such a history.

Methods

Adult household residents selected from the Israeli population register were assessed with a psychiatric structured interview; the analyzed sample included 1306 respondents. War measures included self-reported days in an exposed region.

Results

Among those with a history of maltreatment, those in a war-exposed region for 30+ days had 5.3 times the odds of subsequent alcohol disorders compared to those exposed 0 days (95%C.I. 1.01–27.76), controlled for relevant confounders; the odds ratio for those without this history was 0.5 (95%C.I. 0.25–1.01); test for interaction: X2 = 5.28, df = 1, P = 0.02.

Conclusions

Experiencing a fateful stressor outside the control of study participants, civilian exposure to the 2006 Lebanon War, is associated with a heightened the risk of alcohol disorders among those with early adverse childhood experiences. Results suggest that early life experiences may sensitize individuals to adverse health responses later in life.

Keywords: Alcohol disorders, War, Stress, Childhood maltreatment, Israel, Interaction

1. Introduction

Exposure to war is a stress that has profound effects on the mental health of populations, both civilian (Johnson and Thompson, 2008) and military (Dohrenwend et al., 2006; Wessley, 2007). A well-documented literature has shown that wartime experiences increase the risk of psychopathology (Dohrenwend et al., 2006; Erickson et al., 2001; Johnson and Thompson, 2008; Kessler et al., 1995; Morina and Emmelkamp, 2012; Skodol et al., 1996). While exposure to combat stress is associated with the development and persistence of alcohol disorders among soldiers (Scherrer et al., 2008; Stewart, 1996), civilian populations now comprise the majority of casualties in modern warfare (Aboutanos and Baker, 1997; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 1993). A more comprehensive understanding of civilian mental health and substance use responses to war exposure is important for public health in response to war.

Much of the evidence linking war exposure to alcohol disorders is based on military samples. Military samples are predominantly composed of young men (Turner et al., 2007), the population group at highest risk for alcohol disorders (Hasin et al., 2007), raising concerns about generalizability to civilian populations who may also experience widespread exposure to traumatic events during wartime. Hypotheses about the effects of war on civilian populations can potentially be drawn from the literature on terrorism and natural disorders, as these exposures may be analogous in some ways to civilian exposure to the stresses of war. These experiences are largely outside of individual control, are often acute, often render fear and helplessness, and may involve witnessing death and other atrocities. Studies of terrorism and natural disasters in general population samples have found short-term increases in mean population alcohol consumption (DiMaggio et al., 2009; Keyes et al., 2011), but have rarely found increases in alcohol disorders (North et al., 2004, 2010, 2002). Small studies of civilian samples find that exposure to war and terrorism are associated with psychological distress (Dickstein et al., 2012; Hobfoll et al., 2012), but wartime experiences as risk factors for alcohol use disorders in civilian populations remain largely unexplored.

The consequences of war and other traumatic experiences must be considered in the context of factors that may predispose individuals to potentially problematic psychological or behavioral response. A growing body of evidence has shown that events in early childhood are particularly salient predisposing factors for the development of psychopathology after trauma exposure, suggesting that studies of adult traumatic events should take into account potential adverse childhood environments in order to better understand response. Studies find that individuals with childhood trauma exposure, particularly abuse, neglect, or chaotic home environments, are at heightened risk for psychopathology (Bal et al., 2003; Futa et al., 2003; McLaughlin and Hatzenbuehler, 2009; McLaughlin et al., 2009, 2010; Wichers et al., 2009) and heavy alcohol consumption (Keyes et al., 2012b; Young-Wolff et al., 2012) after exposure to stress in adulthood in both civilian and military samples. Childhood maltreatment is associated with increased emotional reactivity (Glaser et al., 2006; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Wichers et al., 2009), disruptions in the ability to adaptively modulate negative emotions (McLaughlin and Hatzenbuehler, 2009; McLaughlin et al., 2009) and problematic coping strategies (Bal et al., 2003; Futa et al., 2003). Individuals who are emotionally reactive and who have limited skills for effectively modulating their emotions following childhood maltreatment may use alcohol or other substances to manage negative affect and arousal following stressful experiences (Carpenter and Hasin, 1998; Cooper et al., 1995; Ham and Hope, 2003). Thus, individuals who experience adversities in childhood may be more sensitized to adverse reactions following stressors occurring in adulthood.

Understanding factors that predict how individuals respond to stressors in adulthood is of substantial public health as well as clinical importance. While child maltreatment is known to be associated with adverse mental health and substance use consequences in adulthood (Keyes et al., 2012a, 2011), there is substantial individual variation among adults with maltreatment histories. Identification of factors that predict adverse outcomes among those affected by maltreatment, such as adult stressful life events, can elucidate the stress process more specifically and illuminate avenues for public health intervention. For example, if child and adult stressors interact to produce problematic alcohol use, clinicians treating individuals exposed to war should consider how stressful experiences over the life course may shape war-related responses, and identify individuals with past history of early-life stressors as particularly vulnerable to subsequent psychopathology.

Assessing the potential interaction of childhood and adulthood stressful experiences in predicting alcohol problems is complicated by the correlation of many of these experiences. Individuals who experience childhood stressors are more likely to experience certain stressful events as adults, such as intimate partner violence (Desai et al., 2002; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; McKinney et al., 2009), neighborhood disorganization (Freisthler, 2004), divorce and other interpersonal stressful experiences (Andrews, 1981; Fergusson and Horwood, 1984; Wolfinger, 2005). The interaction between childhood adversity and these adult stressors in producing adverse responses may be obscured by correlations between exposures occurring at different points in development. Thus, childhood stressors could confound the relation between adult stressors and adverse mental health, in addition to interacting with adult stressors. Only through assessment of adult and/or child stressors that are relatively randomly distributed, thus uncorrelated, can a rigorous assessment of interaction be demonstrated. Consistent with this, studies of the risk for depression and alcohol-related outcomes suggest that the interaction of childhood maltreatment and adult stressors is present (Young-Wolff et al., 2012) or stronger (Harkness et al., 2006) when the adult stress-ors are outside the individual’s control and thus uncorrelated with the childhood stressor. Wartime attacks on civilian populations are another example of one such adult stressor that is largely outside the control of individual civilians, and thus not a consequence of their childhood stressors.

In sum, the present study utilizes a war-time stressor in Israel outside of the control of civilians to rigorously assess the evidence for an interaction between adverse childhood experiences and adult exposure to a stressful event in association with alcohol use disorders. This study examines whether a large household sample of Israelis were at increased risk for alcohol use disorders following their exposure to the Lebanon War of 2006 (Second Lebanon War). The war occurred between the 13th of July and the 14th of August 2006, a period of 33 days (Rubin, 2007), with about 3790 rockets fired into Northern Israel from Lebanon. The Israeli civilian death toll was estimated at 44, with approximately 1500 civilians wounded. We examine how exposure to the war affected risk for subsequent alcohol use disorders, and whether the association between war exposure and alcohol disorders was modified by experiences of childhood maltreatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study procedures

Participants came from a study of genetic and environmental influences on alcohol use that was planned prior to the Second Lebanon War. A population-based sample of adult residents of Jewish ethnicity was selected for the sample from the Israeli Population Register by the Israeli Bureau of the Census. The Israeli Population Register covers household residents in all areas of Israel; potential participants were selected directly from the registry based on their area of residence, age, gender, ethnicity and Former Soviet Union (FSU) immigrant status. Individuals between the age of 21 and 70 were included; those aged between 18 and 21 typically serve in the army and are thus difficult to contact, and those older than 70 would be too unlikely to have substantial levels of alcohol consumptions to achieve main study aims. Males were oversampled as drinking among Israeli women is limited (Shmulewitz et al., 2010). Only those of Jewish ethnicity were included to provide sample homogeneity to address original study genetic questions, while immigrants from the FSU were over-selected to provide a sufficient sample size for to address one of the original study environmental research questions. Interviewers obtained written informed consent as approved by relevant Institutional Review Boards (Shmulewitz et al., 2010, 2011), and administered computer-assisted interviews. Interviewers underwent structured training and supervisor certification. Ongoing supervision included field observation, review of recorded interviews, and telephone verification of participation and responses. Among eligible participants, 1349 were included, for a response rate of 68.9%. Further detail on study design and methodology is found elsewhere (Hasin et al., 2002; Shmulewitz et al., 2010, 2011).

2.2. Sample

Respondents interviewed after August, 2007 (n = 1306) were included in this analysis to ensure temporal order between war exposure and alcohol disorder symptoms. Of these, 76.5% (N = 999) were male; 24.4% (N = 318) were 18–29 years old, 34.6% (N = 452) were 30–44, and 41.0% (N = 536) were 45+; 66.6% (N = 869) were currently married or living together, 24.8 (N = 324) were never married, and 8.6% (N = 112) were previously married; 6.9% (N = 89) had less than baccalaureate education, 60.4% (N = 782) completed high school, and 32.7% (N = 424) completed a university degree; 23.8% (N = 311) were immigrants from the FSU (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study respondents based on history of childhood maltreatment and number of days in war-exposed region during the 2006 Lebanon war among a population-based sample of Israelis (N = 1306).

| Exposure variables

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample

|

Childhood maltreatment

|

Days in a war exposed regiona

|

|||||||

| N | % | Yes | No | X2, df, P-value | 0 | 1–29 | 30–40 | X2, df, P-value | |

| 1306 | – | 116 | 1190 | 947 | 195 | 153 | |||

| Men | 999 | 76.5 | 60.3 | 78.1 | 75.6 | 81.5 | 82.4 | 7.7, 2, P = 0.02 | |

| Women | 307 | 23.5 | 39.7 | 21.9 | 18.5, 1, P = <0.01 | 25.4 | 18.5 | 17.7 | |

| Non-FSUb immigrant | 995 | 76.2 | 76.7 | 76.1 | 77.6 | 77.4 | 66.0 | 10.0, 2, P = <0.01 | |

| FSUb immigrant | 311 | 23.8 | 23.3 | 23.9 | 0.02, 1, P = 0.89 | 22.4 | 22.6 | 34.0 | |

| Age 21–29 | 318 | 24.4 | 18.1 | 25.0 | 24.6 | 25.1 | 22.3 | ||

| Age 30–39 | 339 | 26.0 | 23.3 | 26.2 | 25.7 | 28.7 | 21.6 | ||

| Age 40–49 | 232 | 17.8 | 19.0 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 21.0 | 16.3 | ||

| Age 50–59 | 283 | 21.7 | 30.2 | 20.8 | 21.7 | 18.5 | 26.8 | ||

| Age 60+ | 134 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 6.8, 4, P = 0.15 | 10.8 | 6.7 | 12.4 | 9.5, 8, P = 0.30 |

| Married or living with someone as if married | 869 | 66.6 | 66.4 | 66.6 | 66.3 | 65.1 | 69.1 | ||

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 112 | 8.6 | 14.7 | 8.0 | 7.2, 2, P = 0.03 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 0.78, 4, P = 0.94 |

| Never married | 324 | 24.8 | 19.0 | 25.4 | 24.9 | 26.2 | 23.7 | ||

| Highest degree achieved | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 89 | 6.9 | 11.4 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 3.1 | 12.4 | ||

| Completed high school | 782 | 60.4 | 60.5 | 60.4 | 59.7 | 63.2 | 59.5 | ||

| Completed university degree | 424 | 24.8 | 28.1 | 33.2 | 4.6, 2, P = 0.10 | 32.6 | 33.7 | 33.3 | 5.2, 4, P = 0.26 |

| Unemployed and looking for work >1 month in the past year | |||||||||

| Yes | 157 | 12.0 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 17.0 | ||

| No | 1149 | 88.0 | 85.3 | 88.2 | 0.84, 1, P = 0.36 | 88.5 | 88.7 | 83.0 | 3.9, 2, P = 0.14 |

| Average gross monthly household income | |||||||||

| 0–7500 NIS | 506 | 39.0 | 44.4 | 38.5 | 39.0 | 38.9 | 39.3 | ||

| 7501–17500 NIS | 548 | 42.3 | 42.6 | 42.3 | 43.5 | 36.8 | 42.0 | ||

| 17,501 or more NIS | 242 | 18.7 | 13 | 19.2 | 3.1, 2, P = 0.22 | 17.5 | 24.4 | 18.7 | 5.7, 4, P = 0.22 |

| Prior to past year alcohol disorders | |||||||||

| Yes | 261 | 20.0 | 25.9 | 19.4 | 17.4 | 29.4 | 25.6 | ||

| No | 1045 | 80.0 | 74.1 | 80.6 | 2.7, P = 0.10 | 82.6 | 70.6 | 74.4 | 16.3, 2, P = <0.01 |

| Active military duty during the Lebanon War | |||||||||

| Yes | 149 | 11.4 | 6.9 | 11.9 | 6.7 | 26.7 | 22.2 | ||

| No | 1157 | 88.6 | 93.1 | 88.2 | 2.56, 1, P = 0.11 | 93.4 | 73.3 | 77.8 | 83.1, 2, P = <0.01 |

11 missing values, total N = 1295.

Former Soviet Union.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Lebanon War exposure

Data collection for the study was due to start when the war broke out and hence was delayed. Due to this unexpected event, during the start up delay, we added measures to the in-person interview to capture respondents’ experiences in the war and potential exposure to war-related stressors. Individuals in our sample were distributed throughout Israel, with 19.6% (N = 244) of respondents in the area that sustained at least some rocket fire. Respondents were asked: “During the 2006 war with Lebanon, how many days were you in an area…attacked by rockets or missiles?” Preliminary analyses were conducted to examine the functional form of the relation between days in a war-exposed region and log-odds of alcohol disorders. Because the variable was right-skewed (mean = 5.3 [SD = 11.2], median = 0, mode = 0), we used a three-level categorical variable with the following cut-points: 0 days (N = 947); 1–29 days (N = 195); and 30+ days (N = 153). These cut-points were based on the distribution in the data. Supplementary analyses including other potential cut-offs for days in the region were also conducted, provided as Supplementary Material1. There were 11 missing responses; those individuals were excluded from analyses of this variable.

2.3.2. Narratives elicited by individuals exposed to war

We conducted supplementary analyses using narratives elicited by individuals exposed to war to characterize whether individuals were in great personal danger or not during the war. Individuals who were in an exposed area during the war were asked: “Please describe to me the time you were in the greatest physical danger during the war.” Narratives were given by 134 respondents. Narratives were coded by a trained, bachelor’s-level Israeli rater on a five-point scale from “In great personal danger” to “Not in personal danger”. Use of an independent rater to code narrative experiences of stressful events is considered by some to be a more valid approach than respondent self-report, as it does not rely as heavily on respondent appraisal (Brown, 1989; Dohrenwend, 2000). We conducted test-retest reliability of the independent rater by comparing coding of 12 narratives across nine at least bachelor’s-level Israeli and American raters who received the same training. The resulting ICC was 0.57, indicating fair to good reliability. Examples of experiences coded as representing ‘great’ personal danger (N = 92) include: (a) seeing a missile hitting a helicopter (thus being at risk for falling debris); (b) being in a building when it was hit with a rocket; and (c) moving between bomb shelters during rocket explosions. We dichotomized exposure at great personal danger versus all others (including individuals who were not in a war exposed region).

2.3.3. Rocket exposure based on home address

Because some individuals in highly exposed areas did leave the areas during the war, we did not use home address as the main exposure variable for the study results due to this potential for misclassification. We conducted supplementary analysis, however, using estimated rocket exposure in each area of Israel (Rubin, 2007). There were a total of 19 areas of Israel that were exposed to at least one rocket, and a total of 536 respondents in our sample had a home address in one of these regions. We created a dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent had a home address in an area exposed to at least one rocket compared with all other respondents.

2.3.4. Childhood maltreatment

Childhood maltreatment, endorsed by 8.8% of the sample, was defined by report of at least one of three experiences. (1) Sexual abuse (3.2%) was assessed by “Were you ever sexually assaulted, raped, or molested?” and reporting that this experience first happened before age 18. (2) Neglect (3.7%) was assessed by the question “Before you were 18 years old, were you ever seriously neglected by either of your parents or any of the people who raised you?” (3) Physical abuse (4.7%) was assessed by the question “Before you were 18 years old, were you ever physically attacked or badly beaten up or injured by either of your parents or any of the people who raised you?”.

2.3.5. Alcohol use disorders

The outcome in these analyses was a diagnosis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence (termed “alcohol disorders”) in the past 12 months. Alcohol disorders were diagnosed based on more than 30 symptom items that are used to create DSM-IV diagnoses with the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV). Reliability of the AUDADIS-IV alcohol diagnoses is documented in clinical and general population samples (Chatterji et al., 1997; Grant et al., 2003, 1995; Hasin et al., 1997a) with test-retest reliability ranging from good to excellent (Kappa = 0.70–0.84). Convergent, discriminative and construct validity of AUDADIS-IV alcohol use disorder criteria and diagnoses were shown to be good to excellent in studies worldwide (Hasin and Paykin, 1999; Hasin et al., 1990, 1994, 2003, 1997b). The sample only included individuals who were interviewed at least one year after the war ended, thus reports of past-year alcohol disorders are temporally subsequent to the war. Of the 1306 individuals, 6.8% (N = 89) met criteria for past-year alcohol dependence, and 4.0% (N = 52) met criteria for alcohol abuse, for a total prevalence of 10.8% (N = 141). We included all individuals regardless of prior-to-past-year alcohol disorders, and included history of alcohol disorders prior to the war (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) as a control variable in all adjusted analyses.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Past-year alcohol disorder was the binary outcome for all analyses. Bivariate associations between exposures (Lebanon War, maltreatment) and control variables were assessed with cross-tabulations and chi-square tests.

We assessed the main effects of maltreatment and war exposure on alcohol disorders in the year after the war, both in unadjusted logistic regression models and logistic regression models controlled for covariates that were significantly related to war exposure: gender, age, education, FSU immigration, military service during the conflict, and prior to past year alcohol disorders. While these tests for main effects were not statistically significant (see results), we tested for effect measure modification due to previous work suggesting that risk is heightened only among those who experience maltreatment; given that this is a minority of individuals, main effects may obscure this subgroup at heightened risk.

We then assessed effect measure modification (interaction) between childhood maltreatment and war exposure using a cross-product term in the logistic regression model (using the three-level categorical variable for days in the region, a dichotomous indicator of whether the respondent was in great personal danger during the war, and a dichotomous variable for child maltreatment) and chi-square tests to assess the statistical significance of the difference in odds ratios at various levels of exposure. We also conducted additional analyses of effect measure modification of risk differences. This was done for two reasons. First, odds ratios tend to overestimate the risk ratio when outcomes are common, thus we estimate both to ensure robustness of the effect. Second, interaction of risk differences reflects interaction on an additive scale; additive interaction concurs with conceptual understanding of biological interaction and causal synergism (Rothman, 2012). Because the number of respondents with both 30+ days in a war exposed region and childhood maltreatment was small (N = 11), we used Huber–White robust estimates of weighted least-squares variance (Hobfoll et al., 2012) for risk differences and interaction tests (Besser and Neria, 2012).

3. Results

3.1. Associations among exposure variables

Childhood maltreatment was unrelated to number of days in a war-exposed region (χ2 = 0.62, df = 2, P = 0.73).

3.2. Associations between exposure variables and control variables

Associations between exposure and control variables are shown in Table 1. Women were more likely than men to report childhood maltreatment, as were individuals who were never married, and those of low educational achievement. Men were more likely than women to report more days in a war-exposed region, as were immigrants from the FSU, those with prior-to-past-year alcohol disorders, and those in active military duty during the war. Covariates associated with war exposure were controlled in all adjusted models.

3.3. Main effects of maltreatment and war exposures on alcohol disorders

Individuals who were in a war exposed region 30+ days did not have significantly different risk of alcohol disorders in the year after the war compared to those in the region 0 days (odds ratio = 1.41, 95% C.I. 0.89, 2.23). Individuals who reported childhood maltreatment had 1.15 times the odds of alcohol disorders compared to those that reported no maltreatment (C.I. 0.64, 2.07).

3.4. Effect measure modification between Lebanon War exposures and childhood maltreatment

We tested for effect measure modification of Lebanon War exposure due to previous studies suggesting that risk is heightened only among those who experience maltreatment.

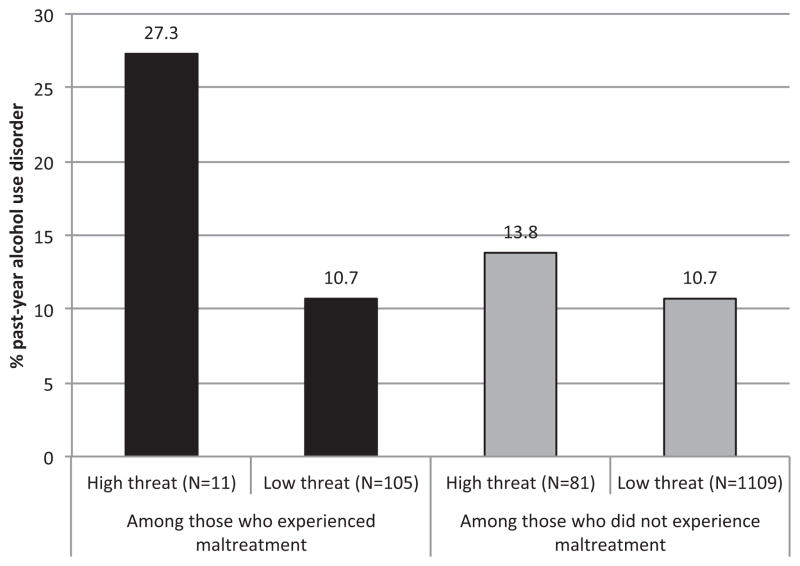

The prevalence of alcohol disorders stratified by childhood maltreatment and days in a rocket-exposed region is shown in Fig. 1. As shown, those with histories of childhood maltreatment who had the highest level of war exposure demonstrated markedly increased prevalence.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of respondents with alcohol disorders by number of days in a war-exposed region as well as history of childhood maltreatment in a population-based sample of Israelis (N = 1295).

As shown in Table 2, among individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment, those who were in a war-exposed region for 30+ days had 5.29 times the odds of alcohol disorders in the year after the war compared to those exposed 0 days (95%C.I. 1.01, 27.76), controlling for relevant confounders. There was no significant effect of war exposure among those with no childhood maltreatment. A direct interaction test for the difference in odds ratios for the effect of 30+ days exposure on alcohol use disorders comparing those with and without child maltreatment was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.28, df = 1, P = 0.02). We also examined alternative cut-points for the number of days in a war-exposed region (see Supplementary Table 1)2 There is a significant interaction between child maltreatment and days in a war-exposed region whether we create a cut-point for high exposure at 30+, 25+, 20+, 15+, 10+, or 5+ days. Among those who were maltreated as children, all but one individual who was exposed more than 5 days were exposed at least 30 days; thus we include the results for 30+ days in Table 2.

Table 2.

Childhood maltreatment and war exposure: effect modification on past-year DSM-IV alcohol disorders among a population-based sample of Israelis (N = 1295).

| Effect among those experiencing childhood maltreatment (N = 115) | Effect among those not experiencing childhood maltreatment (N = 1180) | Test for interaction of the odds ratios | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| OR (95%C.I.) | OR (95%C.I.) | Chi-square, df, P-value | |

| Unadjusted | |||

| 30+ | 5.57 (1.34, 23.24) | 0.88 (0.48, 1.61) | 5.59, 1, P = 0.02 |

| 1–29 | 1.22 (0.24, 6.28) | 1.43 (0.89, 2.30) | 1.54, 1, P = 0.22 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Adjusted* | |||

| 30+ | 5.29 (1.01, 27.76) | 0.50 (0.25, 1.01) | 5.28, 1, P = 0.02 |

| 1–29 | 1.48 (0.24, 9.07) | 0.94 (0.53, 1.68) | 0.57, 1, P = 0.45 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

Bold: P < 0.05

Adjusted for gender, age, education, FSU immigration status, military service during the conflict, and prior to past year alcohol disorders.

When we examined the risk difference for the effect of war exposure on alcohol disorders among those with and without childhood maltreatment, there was also evidence for effect modification. In the model adjusted for covariates, difference in risk differences between 30+ days in a war-exposed region versus 0 days across those with childhood maltreatment compared to those without was 0.25 (95%C.I. 0.49, 0.005, P = 0.04). This indicates that those with both child maltreatment and high exposure to the war had an excess in risk compared to what would be expected given the sum of the risks for high exposure to war and child maltreatment independently of each other.

3.4.1. Supplementary analysis: narrative experiences of exposed persons

Days in the region were strongly associated with personal danger (χ2 = 285.6, df = 2, P < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 2, individuals who were in great threat to physical danger exhibited higher prevalence of post-war alcohol disorders, but only among those who were exposed to childhood maltreatment. Adjusted regression analyses indicated that the results were in the same direction as overall results for days in the region, though less precise: among those who experienced maltreatment, those reporting great personal danger had 2.99 times the odds of an alcohol disorder subsequent to the war (95%C.I. 0.59–15.29), whereas those who did not experience maltreatment had 0.66 times the odds of an alcohol disorder subsequent to the war if in great personal danger (95%C.I. 0.30–1.45). The test for interaction did not reach traditional thresholds for statistical significance (χ2 = 2.72, df = 1, P = 0.10).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of respondents with alcohol disorders by threat to physical integrity as well as history of childhood maltreatment in a general population sample of Israelis (N = 1306).

3.4.2. Supplementary analysis: rocket exposure based on respondent’s home address

Days in the region were strongly associated with home address in a rocket-exposed region (χ2 = 621.7, df = 4, P < 0.001). Adjusted regression analyses indicated that the results were in the same direction as overall results for days in the region, though less precise: among those who experienced maltreatment, those with a home address in a rocket-exposed region had 2.75 times the odds of an alcohol disorder subsequent to the war (95%C.I. 0.54–13.98), whereas those who did not experience maltreatment had 1.44 times the odds of an alcohol disorder subsequent to the war if in great personal danger (95%C.I. 0.88–2.34). The test for interaction was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.54, df = 1, P = 0.45).

4. Discussion

Exposure to the Lebanon War of 2006 among Israeli household residents was associated with an increase in the odds of alcohol use disorders in the first year after the war, but only among those with a childhood history of maltreatment. These results support the hypothesis that adverse experiences early in life sensitize individuals to developing psychopathology following stressful experiences in adulthood, and suggest that a life course perspective is necessary to comprehensively understand the roles of distal and proximal stress in the etiology of alcohol use disorders.

Our results are consistent with two previous studies showing that stressful life events occurring in adulthood increase the risk of alcohol-related outcomes primarily among those who had experience previous childhood maltreatment. Among a population-based sample of predominately African Americans, Keyes et al. (2012a, b) demonstrated that individuals living in disordered neighborhoods were at increased risk for incident binge drinking, but only among those who experienced childhood maltreatment. In a large population-based longitudinal study of twins, Young-Wolff et al. (2012) found that childhood maltreatment interacted with adult stressors to predict drinking quantity and frequency, although only among women and only when stressors were outside the control of the individual. Thus, similar sensitizing effects of childhood maltreatment on alcohol-related outcomes have now been documented in three diverse samples with a wide range of adult stressors.

War exposure had an effect on alcohol use disorders only when childhood maltreatment was also present, but note that maltreatment may be associated with a range of adverse childhood experiences. Children who experience maltreatment are likely embedded in environments with multiple risk factors, such as instability (Dong et al., 2004; Dube et al., 2002), poverty (Turner et al., 2006), and parental dysfunction across multiple domains including substance abuse, criminality, and psychopathology (Besinger et al., 1999; Chaffin et al., 1996; Conron et al., 2009; Dinwiddie and Bucholz, 1993; Kelleher et al., 1994). The pathways through which experiences of stress and maltreatment as a child manifest in psychiatric disorders including alcohol use disorders in adulthood are complex and multifactorial (Keyes et al., 2012a). The present study adds to the growing body of literature that indicates one such pathway. Childhood maltreatment, in the context of a broader set of childhood stressors, may be associated with psychopathology in adulthood by sensitizing individuals to developing mental health problems in the context of adult stress. However, we also acknowledge that because maltreatment coincides with a host of other stressful circumstances, it remains unclear the extent to which the association between maltreatment and alcohol use disorders in the present study is attributable specifically to maltreatment, or the broader stressful context of maltreated children. Regardless of the specificity of the maltreatment effect, however, the results indicate that stressful circumstances in childhood interact with adult stressful experiences in predicting alcohol use disorders. The specific mechanisms underlying this sensitization to psychopathology remain to be elucidated, but a growing lab-based literature indicates that heightened emotional and physiological reactivity to the environment and poor emotion regulation skills may mediate the sensitivity of maltreated children to environmental stressors (Heim and Nemeroff, 2001).

We used an opportunity to examine a stressful life event largely outside the control of individuals experiencing the event. Indeed, individuals who reported childhood maltreatment were not more likely to be exposed to the war than individuals who were not maltreated. However, war exposure was related to some of the study covariates. While the relation between war exposure and active military service and male gender was expected, we also found that FSU immigration status, and past alcohol disorders were related to war exposures. Association of war exposure with these characteristics may be because such individuals had fewer social and economic resources to leave the exposed areas (e.g., to stay in homes of friends or relatives or in hotels elsewhere). However, we controlled for all measured factors associated with war-exposure, and results indicated significant effect measure modification on both the multiplicative and additive scales while controlling for these factors. While the effects of selection into war-exposed regions cannot be definitively ruled out, our results suggest that selection is unlikely to fully account for the observed associations.

Limitations of the present study are noted. There is potential for measurement error in our constructs. Childhood maltreatment is based on retrospective self-report in adulthood. This may introduce some bias into the results (Hardt and Rutter, 2004), as longitudinal studies have documented that child abuse reports, including childhood sexual abuse, are unstable over time and likely underestimated at single time point assessments (Widom and Morris, 1997; Widom and Shepard, 1996). Further, we used three questions regarding specific forms of abuse and neglect to capture maltreatment; these questions may not be sensitive enough to elicit all cases of abuse, thus broader questions on frequency of experiences and a wide range of experiences would be beneficial for future research. We would expect that undercounting of cases would render underestimates of the association between child maltreatment and alcohol disorders, indicating that our results should be considered conservative estimates. Additionally, these data were collected cross-sectionally, thus, reverse causation between outcome and exposure cannot be ruled out definitively. However, we included only respondents who were interviewed more than one year after the Lebanon War, establishing that the occurrence of the war was prior to the measurement of alcohol use disorders.

Our measure of days of a war-exposed region was based on self-report of the respondents. Because many individuals in the sample left the areas of their home address during the war, especially those in highly exposed areas, home address was not as valid an indicator of rocket exposure compared with reports of days in a war-exposed region. Nevertheless, there was an association between reported war exposure and war exposure based on home address, indicating that self-reports are a reliable measure of war exposure, and results using home address in a rocket exposed region as a supplementary exposure indicated that results were in a similar direction as the main study results. Further, we included a supplementary analysis of narratives elicited from respondents describing their experiences during the war. The directions of the effect were again similar to our main analysis; those both highly exposed and who experienced child maltreatment had the highest risk of alcohol disorder onset.

We considered alcohol use disorders only among those interviewed at least one year after the Lebanon War, which excluded 43 individuals. While this establishes temporality between war exposure and alcohol use disorders, we may miss individuals with onset of an alcohol use disorder (either new onset or relapse) immediately after the war. We conducted sensitivity analyses including these 43 individuals, and the results did not change. For example, there remains a significant effect measure modification between spending 30+ days in a war-exposed region and childhood maltreatment in predicting alcohol use disorders, both on the multiplicative (F = 6.48, P = 0.01) and the additive (F = 4.49, P = 0.03) scale. Finally, the present study included only those Jewish ethnicity; other groups were also directly exposed to this conflict including Arab residents of Israel, members of the Israeli Defense Forces, and Lebanese citizens. These groups would also warrant study if data were available.

Finally, the number of individuals in these data with both experiences of child maltreatment and high exposure to the war was limited (N = 11). While we used robust statistical methods to estimate associations given the limited sample size in this group, we caution against strong inference. However, these results are consistent with other studies examining the interaction of child and adult stressors (Keyes et al., 2012b), including those assessing fateful stressors (Young-Wolff et al., 2012), thus, the consistency of results across studies suggests that the findings are unlikely to be spurious.

Despite these limitations, the study has five central strengths. First, respondents were systematically selected from a population-based register with a good response and completion rate for general population studies of this kind. Second, the Lebanon War was a fateful event, outside the control of any study respondent, allowing us to examine the effects of war exposures on civilians. Third, our measurement instruments are well validated and reliable, and we used gold standard approaches to assessing exposure to stressful events. Fourth, our results are robust to a range of demographic and clinical control variables. Finally, as noted above, we examined the joint effects of childhood adversity and adult stress with an adult stressor that was independent of the childhood experiences.

In conclusion, the Lebanon War of 2006, while short in duration, was a stressful event for civilians in the exposed areas. Understanding the impact of such experiences on mental health in civilian populations is critical to allocate resources for treatment and, more broadly, to understand the etiology of psychopathology in response to adverse circumstances. This is especially relevant for civilian populations, who now comprise the majority of casualties in modern warfare (Aboutanos and Baker, 1997; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 1993). Our results indicate that individuals enduring maltreatment as children are particularly vulnerable to alcohol disorders after stressful situations such as war.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants [R01AA013654, U01AA018111, K05AA014223 to D.H.]; Department of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health to [K.K]; and the New York State Psychiatric Institute to [M.W., D.H]. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. We acknowledge the advice of Bruce Dohrenwend in creating the narrative method of war exposure in this study, and the helpful consultations of Dr. Rachel Bar-Hamburger in collecting the data in Israel.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.014.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper. See Appendix A for more details.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper. See Appendix A for more details.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper. See Appendix A for more details.

Contributors

K. Keyes developed the research question, was principally responsible for data analysis, and was principally responsible for drafting the manuscript. D. Shmulewitz contributed to the data analysis and in critical revisions to the manuscript. E. Greenstein was involved with field work for the study, contributed to data analysis and to critical revisions to the manuscript. K. McLaughlin contributed to the development of the research question and to critical revisions to the manuscript. M. Wall contributed to the data analysis and in critical revisions to the manuscript. E. Aharonovich was involved in the conceptualization and design of the study, the development of the research question, and in critical revisions to the manuscript. A. Weizman, A. Frisch, B. Spivak, and B. Grant have been involved in the conception, design, and implementation of the study aims, and have provided critical revisions to the manuscript. D. Hasin was the principal investigator of the study, oversaw all data collection including the design and implementation of all study aims, oversaw the development of this project including the conceptualization the research question, the interpretation of the results, contributed sections and provided critical revisions to the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Aboutanos MB, Baker SP. Wartime civilian injuries: epidemiology and intervention strategies. J Trauma. 1997;43:719–726. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199710000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. A prospective study of life events and psychological symptoms. Psychol Med. 1981;11:795–801. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700041295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal S, Crombez G, Van Oost P, Debourdeaudhuij I. The role of social support in well-being and coping with self-reported stressful events in adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1377–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besinger B, Garland AF, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Caregiver substance abuse among maltreated children placed in out-of-home care. Child Welfare. 1999;78:221–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y. When home isn’t a safe haven: insecure attachment orientations, perceived social support, and PTSD symptoms among Israeli evacuees under missle threat. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW. Life events and measurement. In: Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Life Events and Illness. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin D. A prospective evaluation of the relationship between reasons for drinking and DSM-IV alcohol-use disorders. Addict Behav. 1998;23:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Kelleher K, Hollenberg J. Onset of physical abuse and neglect: psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:171–185. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conron KJ, Beardslee W, Koenen KC, Buka SL, Gortmaker SL. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and child maltreatment in a national sample of families investigated by child protective services. Arch Pediatrics Adolesc Med. 2009;163:922–930. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Arias I, Thompson MP, Basile KC. Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence Vict. 2002;17:639–653. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein BD, Schorr Y, Stein N, Krantz LH, Solomon Z, Litz BT. Coping and mental health outcomes among Israelis living with the chronic threat of terrorism. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:392–399. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio C, Galea S, Li G. Substance use and misuse in the aftermath of terrorism. A Bayesian meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104:894–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK. Psychiatric diagnoses of self-reported child abusers. Child Abuse Negl. 1993;17:465–476. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90021-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, Adams BG, Koenen KC, Marshall R. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science. 2006;313:979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1128944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Loo CM, Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Williamson DF. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence Vict. 2002;17:3–17. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Inter-generational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DJ, Wolfe J, King DW, King LA, Sharkansky EJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptomatology in a sample of Gulf War veterans: a prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:41–49. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Life events and depression in women: a structural equation model. Psychol Med. 1984;14:881–889. doi: 10.1017/s003329170001984x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access, and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2004;26:803–819. [Google Scholar]

- Futa KT, Nash CL, Hansen DJ, Garbin CP. Adult survivors of childhood abuse: an analysis of coping mechanisms used for stressful childhood memories and current stressors. J Fam Violence. 2003;18:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JP, van Os J, Portegijs PJM, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J Psychosomat Res. 2006;61:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Bruce AE, Lumley MN. The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:730–741. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Aharonovich E, Liu X, Mamman Z, Matseoane K, Carr L, Li TK. Alcohol and ADH2 in Israel: Ashkenazis Sephardics, and recent Russian immigrants. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1432–1434. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997a;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: concurrent validity in a nationally representative sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant B, Endicott J. The natural history of alcohol abuse: implications for definitions of alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1537–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Muthuen B, Wisnicki KS, Grant B. Validity of the bi-axial dependence concept: a test in the US general population. Addiction. 1994;89:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Schuckit MA, Martin CS, Grant BF, Bucholz KK, Helzer JE. The validity of DSM-IV alcohol dependence: what do we know and what do we need to know? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:244–252. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060878.61384.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Differentiating DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: community heavy drinkers. J Subst Abuse. 1997b;9:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Hall BJ, Canetti D. Political violence, psychological distress, and perceived health: a longitudinal investigation in the Palestinian Authority. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:9–21. doi: 10.1037/a0018743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. World Disasters Report 1993. Martinus Nijhoff; Dordrecht: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H, Thompson A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher K, Chaffin M, Hollenberg J, Fischer E. Alcohol and drug disorders among physically abusive and neglectful parents in a community-based sample. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1586–1590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin KA, Wall MM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012a;200:107–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Goldmann E, Uddin M, Galea S. Child maltreatment increases sensitivity to adverse social contexts: neighborhood physical disorder and incident binge drinking in Detroit. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012b;122:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney CM, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Nelson S. Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence: findings from a national population-based study of couples. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Kubzansky LD, Dunn EC, Waldinger R, Vaillant G, Koenen KC. Childhood social environment, emotional reactivity to stress, and mood and anxiety disorders across the life course. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:1087–1094. doi: 10.1002/da.20762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina N, Emmelkamp PM. Mental health outcomes of widowed and married mothers after war. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:158–159. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Kawasaki A, Spitznagel EL, Hong BA. The course of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse, and somatization after a natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:823–829. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146911.52616.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Ringwalt CL, Downs D, Derzon J, Galvin D. Postdisaster course of alcohol use disorders in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;68:173–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferbaum B, Spitznagel EL, Cox J, Nixon S, Bunch KP, Smith EM. Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:857–859. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K. Epidemiology: An Introduction. 2. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2012. pp. 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin U. The Rocket Campaign against Israel during the 2006 Lebanon War. The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies; 2007. Online access available at: http://www.biu.ac.il/Besa/MSPS71.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer JF, Xian H, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True WR, Tsuang M, Bucholz KK, Koenen KC. Posttraumatic stress disorder; combat exposure; and nicotine dependence, alcohol dependence, and major depression in male twins. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Beseler C, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes KM, Wall MM, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, Spivak B, Weizman A, Frisch A, Grant BF, Hasin D. Nicotine dependence, abuse and craving: dimensionality in an Israeli sample. Addiction. 2011;106:1675–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Schwartz S, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, Reiff M. PTSD symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in Israeli war veterans. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:717–725. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: a critical review. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JB, Turse NA, Dohrenwend BP. Circumstances of service and gender differences in war-related PTSD: findings from the National Vietnam Veteran Readjustment Study. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:643–649. doi: 10.1002/jts.20245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessley S. Shell Shock to PTSD. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M, Geschwind N, Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom C, Thiery E, Delespaul P, van Os J. Transition from stress sensitivity to a depressive state: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:498–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: part 2. childhood sexual abuse. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Shepard RL. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: part 1. Childhood physical abuse. Psychol Assess. 1996;8:412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH. Understanding the Divorce Cycle: The Children of Divorce in their Own Marriages. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Interactive effects of childhood maltreatment and recent stressful life events on alcohol consumption in adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:559–569. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.