Abstract

Many randomized clinical trials collect multivariate longitudinal measurements in different scales, for example, binary, ordinal, and continuous. Multilevel item response models are used to evaluate the global treatment effects across multiple outcomes while accounting for all sources of correlation. Continuous measurements are often assumed to be normally distributed. But the model inference is not robust when the normality assumption is violated because of heavy tails and outliers. In this article, we develop a Bayesian method for multilevel item response models replacing the normal distributions with symmetric heavy-tailed normal/independent distributions. The inference is conducted using a Bayesian framework via Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation implemented in BUGS language. Our proposed method is evaluated by simulation studies and is applied to Earlier versus Later Levodopa Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease study, a motivating clinical trial assessing the effect of Levodopa therapy on the Parkinson’s disease progression rate.

Keywords: item response theory, latent variable, Markov Chain Monte Carlo, robust inference, clinical trial

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disease that is manifested clinically by tremors (trembling in hands, arms, legs, jaw, or head), rigidity (stiffness of the limbs and trunk), bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and impaired balance [1]. In the USA alone, the estimated prevalence is more than 500,000 people, and about 50,000 new cases are reported annually. Currently, the only established treatments for PD are symptomatic (therapies that only affect the disease symptoms, not the cause) [2]. Many PD clinical trials have been conducted to search for the neuroprotective treatments that are capable of halting or slowing down disease progression. In these clinical trials, patients are repeatedly measured on multiple outcomes of various types (e.g. binary, ordinal, and continuous). Hence, the multilevel data structure has three levels of nesting, that is, multiple measurements (level 1) are nested within measurement occasions (level 2) that are nested within patients (level 3). To analyze these multivariate longitudinal data, the analysis model should account for three sources of correlation, that is, inter-source (different measures at the same visit), intra-source (same measure at different visits), and cross correlation (different measures at different visits) [3].

To this end, multilevel item response theory (IRT) models (referred to as MLIRT) are often used to analyze such multivariate longitudinal data. Within the MLIRT modeling framework, the observed measurements are viewed as imperfect manifestations of the interaction between subject-specific latent traits and measurement-specific parameters (e.g. the measurement’s ability to distinguish PD patients in disease severity). The latent traits are regressed on covariates of interest (e.g. treatment and disease duration) as well as confounding variables. Because the response variable in the regression model is latent rather than observed, this approach is also called latent regression [4–9]. The MLIRT models separate the measurement-specific parameters and subject-specific covariates from manifest data so that both may be understood and studied separately. Advantages of the MLIRT models include better reflection of multilevel data structure, simultaneous estimation of measurement-specific parameters and covariate effects, and accurate inference about high-level measures [10–12]. Given a distribution assumption for the latent variables, the MLIRT models are equivalent to nonlinear mixed models [13]. Marginal maximum likelihood method [8] and Bayesian method [12, 14–19] have been widely used for MLIRT model inference. For the detailed description and summary of the IRT models, please refer to Fox [17] and van der Linden and Hambleton [20].

However, when some outcomes are continuous, the analysis submodel within the IRT framework is a common factor model [21], which assumes normal random errors. Even though normality may be a reasonable model assumption, it may lack robustness in parameter estimation under departure from normality (e.g. heavy tails and outliers) [22]. Moreover, the primary efficacy evaluation in confirmatory clinical trials is often required by agencies to follow the ‘intent-to-treat’ (ITT) principle, that is, the analysis includes all randomized individuals regardless of the abnormal observations. By including all patients who are randomized, the ITT analysis preserves the benefits of randomization and is commonly accepted as the most unbiased approach. Hence, the potential outlying observations cannot be deleted to follow the ITT principle. Some popular data transformation methods (e.g. log, square root, Box–Cox) might generate distributions close to normality. But there are some disadvantages with transformations, for example, (i) transformation provides reduced information on an underlying data generation scheme; (ii) component-wise transformation might not guarantee joint normality; (iii) parameters might be hard to interpret on a transformed scale; and (iv) transformations may not be universal and usually vary with datasets [23]. Alternatively, the approaches based on weighting functions have been proposed to reduce the influence of response disturbances in IRT models [24, 25], whereas the approaches based on the minimum covariance determinant estimator have been used to obtain robust inference in factor analysis [26], principal component analysis [27], and discriminant analysis [28]. From a practical perspective, it is essential to replace the normal distributions with some more flexible symmetric and heavy-tailed distributions. Liu [29] discussed a class of robust distributions known as normal/independent (NI) distributions including student’s t, slash, and contaminated normal distributions [30]. The NI distributions have been applied to linear regression model [31, 32], nonlinear regression model [33], linear mixed model (LME) [22, 34–37], nonlinear mixed model (NLME) [38, 39], LME and NLME with censored responses (LMEC and NLMEC) [23], joint modeling of longitudinal measurements and competing risks [40, 41], structure equation model [42], stochastic volatility models [43, 44], Grubbs’ model [45], and measurement error model [46–48]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no literature on Bayesian inference for the MLIRT models using the NI distributions to relax the normality assumption for the continuous outcomes. In this article, we propose a robust Bayesian parametric method for the MLIRT models on the basis of the NI distributions and apply it to a motivating PD clinical trial.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. We describe a motivating clinical trial, the data structure, and the outlier issue in Section 2. In Section 3 we discuss the MLIRT models, the NI distributions, the Bayesian inference, and the Bayesian model selection criteria. In Section 4 we conduct simulation studies in which the MLIRT models by using the NI distributions are compared with the MLIRT models assuming normal random errors with and without outlying measurements. In Section 5, we apply the proposed method to a motivating clinical trial dataset. Concluding remarks and discussions are given in Section 6.

2. A motivating clinical trial

This article is motivated by the ELLDOPA (Earlier versus Later Levodopa Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease) study, a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized, dose-ranging, double-blind clinical trial conducted from year 1998 to year 2001. This study assessed the effect of levodopa (study drug) on the PD progression rate. A total of 361 patients with early PD were randomly assigned to receive levodopa at a daily dose of 150 mg (low dose, 92 patients), 300 mg (medium dose, 88 patients), and 600 mg (high dose, 91 patients), or a matching placebo (90 patients) for a period of 40 weeks. We combine the patients who received levodopa (271 patients) and refer to them as the treatment group. The details of the ELLDOPA study can be found in Fahn et al. [1].

The outcomes collected include QoL, unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) total score (referred to as UPDRS), status of fatigue (referred to as fatigue), and Schwab and England activities of daily living (referred to as SEADL), measured at four visits, that is, baseline, week 9, week 24, and week 40. QoL is the sum of 32 questions each measured on a 5-point scale (0–4) [49]. It is rescaled to 100 so it is an approximate continuous variable with a larger value reflecting worse clinical outcomes. The UPDRS total score is the sum of 44 questions each measured on a 5-point scale (0–4), and it is approximated by a continuous variable with an integer value from 0 (not affected) to 176 (most severely affected). Fatigue is the sum of 31 questions, and it is approximated by a continuous variable with integer value from 0 (not affected) to 182 (severe) [50]. The SEADL (ordinal variable with integer value from 0 to 100 incrementing by 5, with larger value reflecting better clinical outcomes) is a measurement of activities of daily living [51]. We recode the outcome SEADL so that higher values in all outcomes are worse clinical conditions. Moreover, we combine some categories in SEADL with zero or a small number of patients so that it has 7 categories.

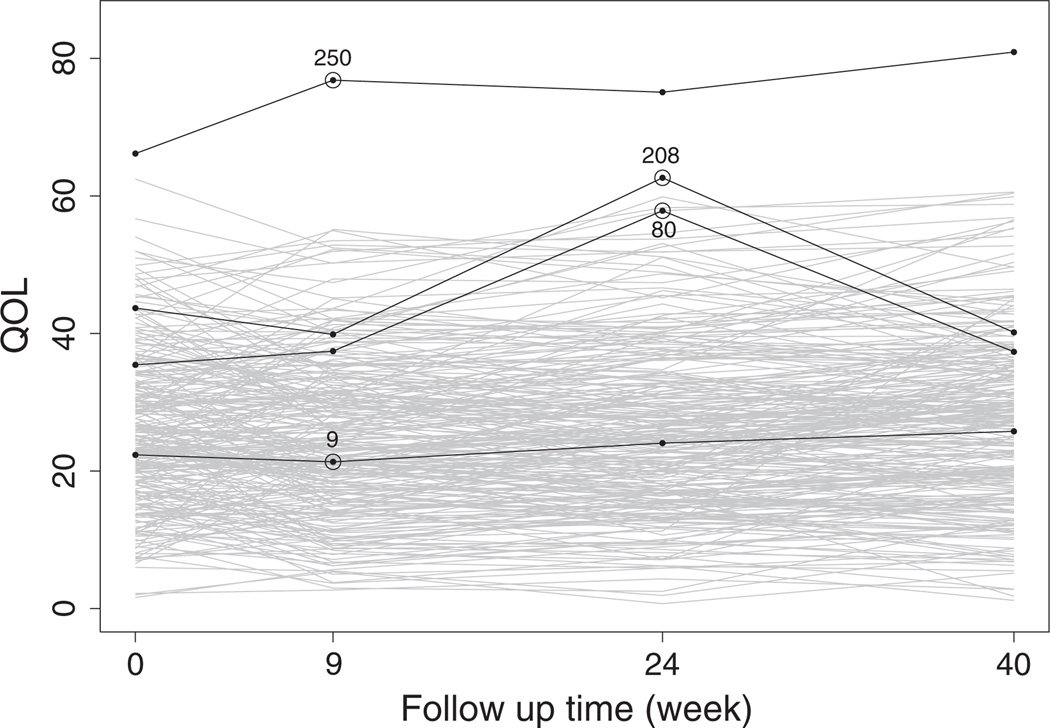

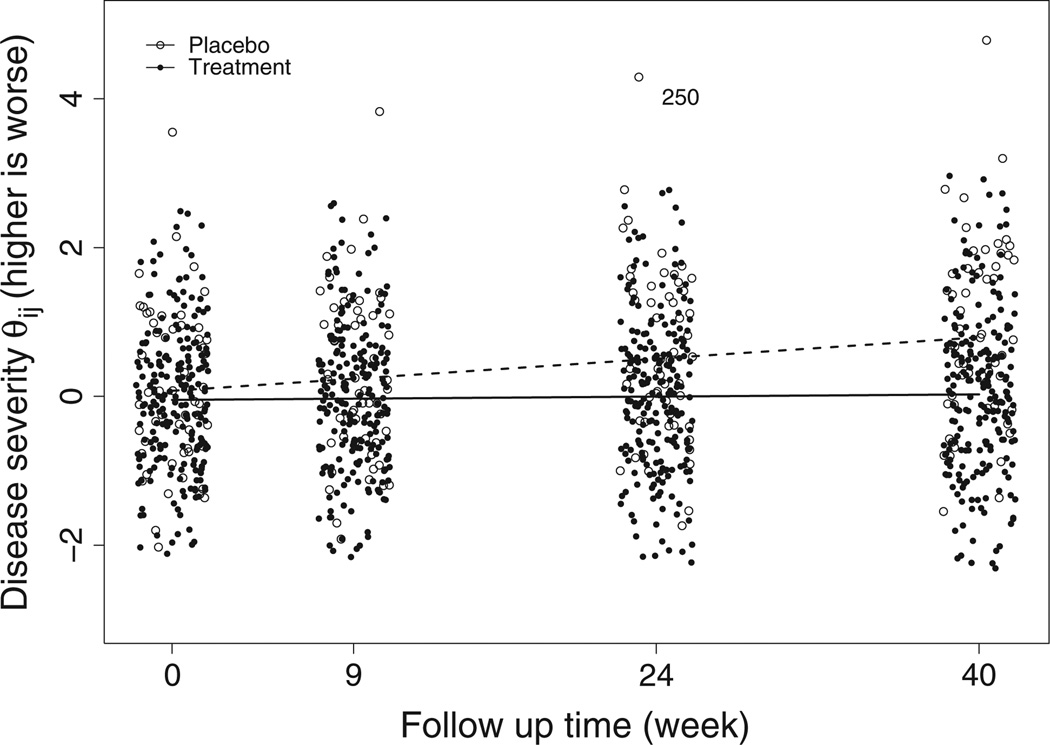

Figure 1 displays the longitudinal profiles of the outcome QoL. Because PD is a slow progression disease, it is unexpected to observe sudden value change in the outcome variables. Patients 80 and 208 have a change of 20.42 and 22.78 units, respectively, in the outcome QoL from week 9 visit to week 24 visit. Hence, these two measurements are potentially outlying observations. Patient 250 has much higher (worse) QoL values than all other patients. Patient 9 appears near the ‘center’ among all measurements. These four patients will be used later for further discussion. We are interested in investigating how the outlying measurements would affect the inference within the MLIRT modeling framework.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal profile plots of the observed QoL measurements. Numbers 9, 80, 208, and 250 denote four patients to be used for further discussion.

3. The robust item response model formulation and estimation

3.1. The multilevel item response model

Ignoring the outlying observation issue for the moment, we introduce the MLIRT model. The level 1 model describes item responses at a specific time point. The level 2 model accounts for variation in the latent traits across time within patient and between patients. Specifically, let yijk (binary, ordinal, and continuous) be the observed outcome k (k = 1,…,K) from patient i (i = 1,…,N) at visit j (j = 1,…,J, where j = 1 is baseline). Throughout the article, we code all outcomes so that larger observation values are worse clinical conditions. Let yij = (yij1,…,yijk,…,yijK)′ be the vector of observation for patient i at visit j, and let yi = (yi1,…,yiK)′ be the outcome vector across visits. We model the binary outcomes, the cumulative probabilities of ordinal outcomes, and the continuous outcomes by using a two-parameter submodel [52], a graded response submodel [53], and a common factor submodel [21], respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where random error with being the variance of continuous outcome k, ak is the outcome-specific ‘difficulty’ parameter, and bk is the outcome-specific ‘discriminating’ parameter that is always positive and represents the discrimination of outcome k, that is, the degree to which outcome k discriminates between patients with different latent disease severity θij. In model (2), the ordinal outcome k has nk categories and nk − 1 thresholds ak1,…,akl,…, aknk−1 that must satisfy the order constraint ak1 < …< akl <…< aknk−1. The probability that patient i being in category l on outcome k at visit j is p (Yijk = l|θij) = p(Yijk ≤ l|θij) − p(Yijk ≤ l− 1|θij). The latent variable θij is continuous and it indicates patient i’s unobserved disease severity at visit j, with a higher value denoting more severe status. Models (1) to (3) consist of level 1 model that describes the item responses as functions of the outcome-specific parameters and the subject-specific latent variable at a certain visit.

At level 2, we model the disease severity θij as a function of covariates, visit time, and random effects

| (4) |

where Xi0 and Xi1 are patient i’s covariate vectors including some covariates of interest (e.g. treatment assignment) and potential confounding variables (e.g. age and gender), Xi0 and Xi1 can share part of or all the covariates, tij is the visit time variable with ti1 = 0 for baseline, random intercept ui0 and random slop ui1 determine the subject-specific baseline disease severity and disease progression rate, respectively. The random effects ui0 and ui1 can be assumed either independent or correlated. We let ui = (ui0, ui1)′ and assume ui0 ~ N01, , and corr(ui0, ui1) = ρ. Model (4) is a latent trait regression model assuming that each patient has subject-specific baseline disease severity after adjusting for the covariate vector Xi0 and that the disease severity changes linearly with subject-specific slope depending on the covariate vector Xi1. We now give an example to further illustrate model (4). If no covariate is in Xi0 and only the treatment assignment variable is included in Xi1, θij = ui0 + [β10 + β11Ii (trt) + ui1]tij, where I(·) is an indicator function (1 if treatment and 0 otherwise). In this model, β10 and β10 + β11 denote the disease progression rates for placebo and treatment patients, respectively, with β11 being the change in disease progression rate introduced by the treatment. The significant negative coefficient β11 indicates that the treatment slows down the disease progression. The combined level 1 and level 2 models are MLIRT with subject-specific covariance (referred to as subject-specific MLIRT models) [12, 14–17, 54]. The underlying assumption of linear disease progression rate in model (4) can be relaxed by adding the quadratic or higher-order term of time t, for example, , where Xi0, Xi1, and Xi2 can share part of or all the covariates.

All three sources of correlations illustrated in Section 1 are accounted for via the random effect vector ui. It is well-known that item response models are overparameterized because they have more parameters than can be estimated from the data [17]. Hence, additional constraints on the location and scale of the latent disease severity are required to make models identifiable. In the subject-specific MLIRT models specified in the previous text, we establish the location and scale of the latent disease severity by setting Eui0 = Eui1 = 0 and Var[ui0] = 1 so that at t = 0 (baseline), the disease severity θij follows standard normal distribution.

Under the local independence assumption (i.e. conditioning on the random effect vector ui, all components in yij are independent), the full likelihood of patient i across all visits is

| (5) |

For notation convenience, we let the difficulty parameter vector be , with ak = (ak1,…, aknk−1)′, the discrimination vector be b = (b1,…,bK)′, and , the parameter vector Φ (a′, b′, β′, ρ, σu, σk)′. We thereafter refer to the MLIRT model assuming normal random errors for the common factor submodel as M1.

3.2. Normal/idependent distributions

In Section 3.1, we assume normal random errors for the common factor submodel, making inferences sensitive to the presence of outliers [22]. In this section, we construct the robust MLIRT models using the NI distributions.

An element of the NI family [30, 55] is defined as the distribution of the p-dimensional random vector y = μ + w−1/2e, where μ is a location vector, e is a normally distributed random vector with mean zero and covariance matrix Σ, w is a positive weight variable with density p(w|ν), ν is a scalar or vector valued parameter. Given w, y follows a normal distribution N(y|μ,Σ) with the marginal density of y given by NI(y|μ, Σ, ν) = ∫ p(y|μ, Σ, w)p(w|ν)d w. The NI family provides a class of symmetric heavy-tailed distributions that consist of the multivariate version of student’s t, slash, and contaminated normal distributions. When the density p(w|ν) degenerates to w = 1 (e.g. when ν → ∞), NI(y|μ, Σ, ν) becomes a normal distribution as a special case.

A univariate NI distribution [30, 55], when applied to the common factor submodel (3), is, , where with , the weight wijk is a positive random variable with density p(wijk|ν), where the tuning parameter ν > 0. The NI distributions provide a group of symmetric heavy-tailed distributions of . In this article, we consider student’s t and slash distributions. Specifically, follows student’s t distribution t (0, , ν), where the tuning parameter ν representing degree of freedom, when wijk ~ Gamma(ν/2; ν/2). In addition, follows slash distribution with tuning parameter ν, when wijk ~ Beta(ν, 1). Although ν in the slash distribution needs to be estimated from the data, ν in student’s t distribution can be either estimated from the data or pre-specified to a small value, for example, ν = 3 or 4. General principles of parsimony suggest that ν be fixed for small datasets and estimated for large ones [32]. Lange et al [32] suggests that estimated values of ν below 1 should be regarded with suspicion. When ν → ∞, the distributions Gamma(ν/2; ν/2) and Beta(ν, 1) degenerate to 1, i.e., wijk ≡ 1. In this case, and the NI distributions reduce to the normal distributions. In practice, the weight variable wijk can be estimated and be used for outlier detection. Specifically, if the posterior distribution of wijk has high density close to 0, it indicates that the corresponding observation can be a potential outlier [34]. Detailed examples of this outlier detection technique will be given in Section 5. For notation convenience, we let wi = {wijk, j = 1,…,J, k = 1,…,K} and the parameter vector is Φ = (a′, b′, β′, ρ, σu, σk, ν)′. The full likelihood of patient i across all visits is

| (6) |

Henceforth, we refer to the MLIRT models by using the NI distributions in the common factor submodel as the NI-MLIRT models. We consider three NI-MLIRT models in this article, that is, student’s t distribution with ν = 4 (refer to as M2), Student’s t distribution with ν estimated (refer to as M3), and slash distribution (refer to as M4).

3.3. Bayesian inference

To infer the unknown parameter vector Φ, we use Bayesian inference based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) posterior simulations. We use vague priors on all elements in the parameter vector Φ . Specifically, the prior distributions of all elements in β are N(0, 100). We use the prior distribution bk ~ Gamma(0.001, 0.001), k = 1,…,K, to ensure positivity. The prior distribution for the difficulty parameter ak of the continuous outcomes is ak ~ N(0, 10000), because some continuous measurements are quite large. To obtain the prior distributions for the threshold parameters of ordinal outcome k, we let ak1 N(0, 100), and akl = ak,l−1 + δl for l = 2; nk − 1, with δl ~ N(0, 100)I(0,), that is, normal distribution left censored at 0. We use the prior distribution ρ ~ Uniform[−1, 1], and σk, σu, ν ~ Gamma(0.001, 0.001).

The model fitting is performed in OpenBUGS (OpenBUGS version 3.2.2) by specifying the likelihood function and the prior distribution of all unknown parameters. We use history plots available in OpenBUGS and view the absence of apparent trend in the plot as evidence of convergence. In addition, we use Gelman–Rubin diagnostic to ensure the scale reduction R̂ of all parameters are smaller than 1.1 [56].

3.4. Bayesian model selection criteria

There are a wide variety of model selection criteria in Bayesian inference. The conditional predictive ordinate (CPO) [57–60] has been widely used to assess model fit and model selection. Let y be the full data and y(i) be the data with subject i omitted. The CPO for subject i is defined as

| (7) |

where p( Φ |y(i)) is the posterior density of Φ given data y(i). CPO is a form of cross-validation with high value indicating that the data for subject i can be accurately predicted by a model based on the data from all other subjects. Hence, a model with larger CPOi for all subjects suggests a better fit. Although the close form of CPOi is not available for our proposed model, a Monte Carlo estimator of CPOi can be obtained by MCMC samples from posterior distribution p( Φ |y), with M being the total number of post burn-in samples. Because p(yi|y(i)) = p(y)/p(y(i)) = 1/∫ p( Φ |y)/p(yi|y(i), Φ )d Φ , a harmonic mean approximation of CPOi is [58]. A summary statistics of for all subjects is the log pseudo-marginal likelihood (LPML) defined as . A larger value of LMPL indicates better fit of the model.

Moreover, we adopt a model selection approach by using the deviance information criterion (DIC) proposed by Spiegelhalter et al. [61]. The DIC provides an assessment of model fitting and a penalty for model complexity. The deviance statistic is defined as D(Φ) = −2 log f (y|Φ) + 2 log h(y), where f (y|Φ) is the likelihood function for the observed data y given the parameter vector Φ and h(y) denotes a standardizing function of the data alone that has no impact on model selection [60]. The DIC is defined as DIC = 2D̅ − D(Φ̅) = D̅ + pD, where D̅ = EΦ|y[D] is the posterior mean of the deviance, D(Φ̅) = D(EΦ|y[Φ̅]) is the deviance evaluated at the posterior mean Φ̅ of the parameter vector, and pD = D̅−D(Φ̅) is the effective number of parameters. A smaller value of DIC indicates a better-fitting model.

We also use the expected Akaike information criterion (EAIC) and the expected Bayesian (or Schwarz) information criterion (EBIC) as model selection tools [60]. The EAIC and EBIC can be estimated as EAIC = D̅ + 2p and EBIC = D̅ + plog(N), where p is the number of elements in the parameter vector Φ. Smaller values of EAIC and EBIC indicate better fit of the model.

4. Simulation studies

In this section, we conduct three simulation studies to compare the performance of two NI-MLIRT models M2 and M4, and the MLIRT model M1. The data structure of the simulated datasets is similar to the motivating ELLDOPA study and has two continuous outcomes and two ordinal outcomes with seven categories, and five visits (baseline and four follow-up visits, J = 5).

In the first simulation study, both continuous outcomes follow normal distributions. In the second and the third simulation studies, the first continuous outcome mostly follows a normal distribution but has 3% and 5% outliers, respectively, whereas the second continuous outcome follows a normal distribution. In all simulation studies, we generate 100 datasets with sample size N = 400 and no missing data. Each dataset is generated using the following algorithm.

Consider the treatment assignment variable xi as the only covariate, simulate xi ~ Bernoulli(0.5).

Set β = (0.4, −0.5), ρ = 0.4, and σu = 1.3, simulate the random effects vector ui ~ N2(0,Σ) with Σ being a 2 × 2 matrix denoted by ((1, ρσu), (ρσu, )), and generate θij for j = 1,…,J from model (4) with Xi0 = 0 and Xi1 = xi.

To generate outliers, simulate 3% or 5% of the random errors εij1 from normal distributions N(60, 100) and N(−60m 100) with rates 30% and 70%, respectively. Set σ1 = 5 and simulate the rest of the random errors . Set a1 = 25, b1 = 10, and generate the first continuous outcome yij1 from model (3).

Assuming no outlier in the second continuous response, set σ2 = 20, and simulate the random errors for j = 1,…,J. Set a2 = 80, b2 = 18, and generate the second continuous outcome yij2 from model (3).

Set a3 = (−2.7, −0.6, 2, 2.8, 5, 6), b3 = 2.0, a4 = (−0.1, 1, 1.8, 2.6, 3.3, 4), b4 = 0.4, and simulate ordinal outcomes yij3 and yij4 from model (2) for j = 1,…,J.

Repeat Steps 1 to 5 until the responses of all patients are generated.

We apply the Bayesian framework in Section 3.3 to obtain samples from the posterior distributions of the parameters of interest. For each dataset in all simulation studies, we run three parallel MCMC chains with overdispersed initial values. Each chain is run for 30,000 iterations, the first 20,000 iterations are discarded as a burn-in, and the next 10,000 samples are used to calculate the joint posterior distribution of the parameters of interest.

The results from models M1, M2, and M4 of the first simulation study with no outliers are compared in Table I. In this table, we label the average of the posterior means minus the true values as bias, the square root of the average of the variances as standard error (SE), the standard deviation of the posterior means as SD, and the coverage probabilities of 95% equal-tail CI as CP. The results suggest that all three models generate comparable results, that is, the bias is negligible, SE is close to SD, and the credible interval coverage probabilities are reasonably close to nominal level of 95%.

Table I.

True values (True), bias, standard error (SE), standard deviation (SD), and coverage probabilities (CP) of 95% credible intervals for models M1, M2, and M4, when there are no outliers.

| Results for model M1 | Results for model M2 | Results for model M4 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | |

| a1 | 25.000 | 0.003 | 0.520 | 0.543 | 0.930 | −0.057 | 0.524 | 0.521 | 0.920 | 0.001 | 0.520 | 0.504 | 0.930 |

| b1 | 10.000 | 0.014 | 0.378 | 0.412 | 0.910 | 0.075 | 0.383 | 0.398 | 0.930 | −0.010 | 0.381 | 0.378 | 0.950 |

| a2 | 80.000 | −0.020 | 1.017 | 1.024 | 0.980 | −0.085 | 1.023 | 0.932 | 0.970 | −0.006 | 1.016 | 1.013 | 0.950 |

| b2 | 18.000 | −0.033 | 0.701 | 0.751 | 0.930 | 0.062 | 0.710 | 0.757 | 0.960 | −0.040 | 0.709 | 0.680 | 0.960 |

| a31 | −2.700 | 0.009 | 0.139 | 0.138 | 0.940 | 0.019 | 0.139 | 0.129 | 0.980 | −0.013 | 0.140 | 0.138 | 0.960 |

| a32 | −0.600 | 0.007 | 0.122 | 0.131 | 0.940 | 0.008 | 0.122 | 0.124 | 0.960 | 0.002 | 0.122 | 0.125 | 0.930 |

| a33 | 2.000 | −0.004 | 0.132 | 0.145 | 0.920 | −0.004 | 0.132 | 0.129 | 0.960 | 0.012 | 0.132 | 0.123 | 0.960 |

| a34 | 2.800 | −0.008 | 0.141 | 0.149 | 0.950 | −0.009 | 0.141 | 0.145 | 0.960 | 0.013 | 0.142 | 0.139 | 0.950 |

| a35 | 5.000 | −0.017 | 0.186 | 0.183 | 0.930 | −0.017 | 0.186 | 0.187 | 0.950 | 0.034 | 0.188 | 0.162 | 0.950 |

| a36 | 6.000 | −0.004 | 0.213 | 0.220 | 0.930 | 0.000 | 0.213 | 0.216 | 0.960 | 0.052 | 0.216 | 0.194 | 0.970 |

| b3 | 2.000 | −0.004 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.930 | 0.005 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.930 | 0.011 | 0.095 | 0.092 | 0.960 |

| a41 | −0.100 | −0.009 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.940 | −0.011 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.960 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.060 | 0.890 |

| a42 | 1.000 | −0.005 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.960 | −0.004 | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.970 | −0.001 | 0.057 | 0.061 | 0.940 |

| a43 | 1.800 | 0.005 | 0.068 | 0.064 | 0.960 | 0.002 | 0.068 | 0.064 | 0.980 | 0.012 | 0.068 | 0.070 | 0.950 |

| a44 | 2.600 | 0.015 | 0.087 | 0.084 | 0.940 | 0.006 | 0.086 | 0.082 | 0.950 | 0.007 | 0.087 | 0.083 | 0.980 |

| a45 | 3.300 | 0.023 | 0.112 | 0.110 | 0.960 | 0.014 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.970 | 0.013 | 0.111 | 0.101 | 0.970 |

| a46 | 4.000 | 0.042 | 0.148 | 0.141 | 0.980 | 0.016 | 0.146 | 0.131 | 0.990 | 0.018 | 0.146 | 0.155 | 0.930 |

| b4 | 0.400 | −0.002 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.930 | −0.003 | 0.027 | 0.024 | 0.970 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.930 |

| β10 | 0.400 | −0.005 | 0.091 | 0.095 | 0.940 | 0.001 | 0.091 | 0.098 | 0.960 | −0.002 | 0.092 | 0.083 | 0.970 |

| β11 | −0.500 | 0.010 | 0.124 | 0.137 | 0.910 | 0.008 | 0.123 | 0.132 | 0.910 | 0.002 | 0.126 | 0.120 | 0.970 |

| ρ | 0.400 | −0.008 | 0.045 | 0.042 | 0.980 | −0.003 | 0.045 | 0.040 | 0.980 | −0.004 | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.950 |

| σu | 1.300 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.060 | 0.970 | 0.004 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.940 | 0.006 | 0.065 | 0.058 | 0.970 |

Table II displays the results of the second simulation study with 3% of outliers in the first continuous outcome. The results from models M2 and M4 indicate that the estimates of all parameters have negligible bias and SE being close to SD. The coverage probabilities of 95% credible intervals are all reasonably around the nominal value. In contrast, model M1 gives severely biased estimates, large SD and SE, and low coverage probabilities for the outcome-specific parameters a1 and b1, because the presence of outliers clearly violates the normality assumption for the first continuous outcome. Model M1 provides reasonable estimates to all other parameters because the information from other response variables are sufficient to estimate other outcome-specific parameters, the regression parameter vector β, and the random effect related parameters ρ and σu. Another interesting phenomena is that models M2 and M4 provide slightly smaller estimates of SE and SD for all parameters. Furthermore, in the presence of 5% outliers in the first continuous outcome, the bias, SE, SD, and CP of the parameter a1 and b1 from model M1 further deteriorate, whereas the estimates for all other parameters are still reasonable (Table III). In comparison, models M2 and M4 still provide reasonable estimates for all parameters. Although the outliers do not have notable impact on the estimates and inference of the regression parameter β1 in Tables II and III, the biased estimates of b1 leads to misleading clinical interpretations and conclusions, because the expected change of continuous variable yij1 from baseline (ti1 = 0) to time tij is b1tijXi1β1 (i.e. E[yij1 − yi11] = b1tijXi1β1).

Table II.

True values (True), bias, standard error (SE), standard deviation (SD), and coverage probabilities (CP) of 95% credible intervals for modelsM1,M2, and M4, when there are 3% outliers in the first continuous response.

| Results for model M1 | Results for model M2 | Results for model M4 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | |

| a1 | 25.000 | −0.741 | 0.628 | 0.629 | 0.790 | −0.025 | 0.516 | 0.515 | 0.920 | −0.010 | 0.519 | 0.514 | 0.910 |

| b1 | 10.000 | −0.135 | 0.448 | 0.462 | 0.940 | −0.014 | 0.377 | 0.382 | 0.920 | −0.008 | 0.376 | 0.387 | 0.940 |

| a2 | 80.000 | −0.009 | 1.039 | 1.093 | 0.930 | −0.036 | 1.010 | 1.043 | 0.940 | −0.024 | 1.013 | 1.033 | 0.940 |

| b2 | 18.000 | −0.052 | 0.786 | 0.814 | 0.960 | −0.041 | 0.702 | 0.695 | 0.950 | −0.035 | 0.699 | 0.697 | 0.940 |

| a31 | −2.700 | −0.006 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.940 | −0.012 | 0.140 | 0.146 | 0.960 | −0.011 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.960 |

| a32 | −0.600 | 0.005 | 0.124 | 0.128 | 0.930 | 0.008 | 0.122 | 0.128 | 0.930 | 0.004 | 0.122 | 0.126 | 0.910 |

| a33 | 2.000 | 0.015 | 0.135 | 0.134 | 0.960 | 0.016 | 0.132 | 0.128 | 0.960 | 0.014 | 0.132 | 0.125 | 0.960 |

| a34 | 2.800 | 0.016 | 0.145 | 0.151 | 0.940 | 0.021 | 0.141 | 0.143 | 0.940 | 0.017 | 0.142 | 0.141 | 0.950 |

| a35 | 5.000 | 0.031 | 0.196 | 0.177 | 0.960 | 0.044 | 0.188 | 0.161 | 0.950 | 0.039 | 0.188 | 0.164 | 0.960 |

| a36 | 6.000 | 0.044 | 0.226 | 0.202 | 0.970 | 0.063 | 0.216 | 0.195 | 0.960 | 0.057 | 0.216 | 0.197 | 0.950 |

| b3 | 2.000 | 0.010 | 0.103 | 0.096 | 0.950 | 0.016 | 0.095 | 0.091 | 0.950 | 0.013 | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.970 |

| a41 | −0.100 | −0.002 | 0.052 | 0.060 | 0.890 | −0.002 | 0.052 | 0.061 | 0.890 | −0.001 | 0.052 | 0.060 | 0.900 |

| a42 | 1.000 | −0.001 | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.940 | 0.000 | 0.057 | 0.059 | 0.940 | −0.001 | 0.057 | 0.060 | 0.950 |

| a43 | 1.800 | 0.013 | 0.068 | 0.072 | 0.950 | 0.011 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.960 | 0.012 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.950 |

| a44 | 2.600 | 0.008 | 0.087 | 0.086 | 0.960 | 0.006 | 0.087 | 0.085 | 0.970 | 0.006 | 0.087 | 0.081 | 0.980 |

| a45 | 3.300 | 0.019 | 0.112 | 0.106 | 0.960 | 0.017 | 0.111 | 0.101 | 0.970 | 0.012 | 0.111 | 0.099 | 0.980 |

| a46 | 4.000 | 0.025 | 0.147 | 0.158 | 0.930 | 0.029 | 0.147 | 0.154 | 0.930 | 0.018 | 0.146 | 0.155 | 0.930 |

| b4 | 0.400 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.920 | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.910 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.030 | 0.930 |

| β10 | 0.400 | −0.004 | 0.094 | 0.088 | 0.950 | 0.001 | 0.090 | 0.087 | 0.940 | −0.001 | 0.090 | 0.089 | 0.920 |

| β11 | −0.500 | −0.003 | 0.130 | 0.129 | 0.910 | 0.003 | 0.125 | 0.127 | 0.960 | −0.003 | 0.122 | 0.124 | 0.920 |

| ρ | 0.400 | −0.001 | 0.050 | 0.054 | 0.930 | −0.005 | 0.045 | 0.046 | 0.970 | −0.004 | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.950 |

| σu | 1.300 | 0.007 | 0.073 | 0.070 | 0.960 | 0.005 | 0.064 | 0.059 | 0.960 | 0.006 | 0.064 | 0.059 | 0.950 |

Note: Large bias, large SE and SD, and poor CP are highlighted in boldface.

Table III.

True values (True), bias, standard error (SE), standard deviation (SD), and coverage probabilities (CP) of 95% credible intervals for models M1, M2, and M4, when there are 5% outliers in the first continuous response.

| Results for model M1 | Results for model M2 | Results for model M4 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | Bias | SE | SD | CP | |

| a1 | 25.000 | −1.227 | 0.691 | 0.720 | 0.530 | 0.054 | 0.519 | 0.568 | 0.900 | 0.072 | 0.525 | 0.527 | 0.910 |

| b1 | 10.000 | −0.230 | 0.470 | 0.473 | 0.940 | 0.060 | 0.375 | 0.350 | 0.950 | −0.007 | 0.373 | 0.391 | 0.940 |

| a2 | 80.000 | 0.064 | 1.043 | 1.188 | 0.910 | 0.140 | 1.014 | 1.113 | 0.930 | 0.108 | 1.025 | 1.109 | 0.900 |

| b2 | 18.000 | 0.054 | 0.801 | 0.825 | 0.930 | −0.072 | 0.700 | 0.634 | 0.960 | −0.020 | 0.695 | 0.701 | 0.940 |

| a31 | −2.700 | −0.006 | 0.144 | 0.152 | 0.940 | −0.018 | 0.140 | 0.155 | 0.920 | −0.018 | 0.141 | 0.141 | 0.950 |

| a32 | −0.600 | 0.001 | 0.124 | 0.140 | 0.900 | −0.001 | 0.122 | 0.139 | 0.920 | −0.003 | 0.123 | 0.135 | 0.930 |

| a33 | 2.000 | 0.001 | 0.135 | 0.135 | 0.940 | −0.001 | 0.132 | 0.134 | 0.970 | −0.003 | 0.133 | 0.122 | 0.970 |

| a34 | 2.800 | 0.007 | 0.145 | 0.152 | 0.940 | 0.003 | 0.142 | 0.150 | 0.920 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.140 | 0.950 |

| a35 | 5.000 | 0.015 | 0.196 | 0.160 | 0.970 | 0.034 | 0.188 | 0.153 | 0.970 | 0.024 | 0.188 | 0.149 | 0.970 |

| a36 | 6.000 | 0.019 | 0.226 | 0.182 | 0.980 | 0.033 | 0.216 | 0.179 | 0.960 | 0.039 | 0.216 | 0.182 | 1.000 |

| b3 | 2.000 | 0.012 | 0.103 | 0.095 | 0.950 | 0.004 | 0.094 | 0.086 | 0.970 | 0.012 | 0.094 | 0.090 | 0.960 |

| a41 | −0.100 | −0.002 | 0.052 | 0.063 | 0.850 | −0.005 | 0.052 | 0.057 | 0.900 | 0.001 | 0.052 | 0.062 | 0.890 |

| a42 | 1.000 | −0.002 | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.930 | −0.006 | 0.057 | 0.061 | 0.920 | −0.002 | 0.057 | 0.063 | 0.920 |

| a43 | 1.800 | 0.013 | 0.068 | 0.075 | 0.940 | 0.008 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.960 | 0.015 | 0.068 | 0.072 | 0.940 |

| a44 | 2.600 | 0.001 | 0.087 | 0.093 | 0.960 | 0.006 | 0.087 | 0.086 | 0.960 | 0.010 | 0.087 | 0.085 | 0.970 |

| a45 | 3.300 | 0.014 | 0.112 | 0.110 | 0.950 | 0.022 | 0.112 | 0.106 | 0.960 | 0.016 | 0.111 | 0.101 | 0.960 |

| a46 | 4.000 | 0.024 | 0.147 | 0.157 | 0.950 | 0.024 | 0.147 | 0.167 | 0.940 | 0.022 | 0.146 | 0.156 | 0.940 |

| b4 | 0.400 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.930 | −0.001 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.920 | 0.003 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.930 |

| β10 | 0.400 | −0.005 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.940 | 0.006 | 0.091 | 0.092 | 0.930 | 0.010 | 0.091 | 0.095 | 0.930 |

| β11 | −0.500 | −0.006 | 0.131 | 0.141 | 0.920 | −0.018 | 0.123 | 0.131 | 0.900 | −0.010 | 0.123 | 0.134 | 0.930 |

| ρ | 0.400 | −0.002 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.950 | −0.003 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.960 | −0.004 | 0.045 | 0.046 | 0.950 |

| σu | 1.300 | 0.001 | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.950 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.059 | 0.970 | 0.002 | 0.064 | 0.063 | 0.960 |

Note: Large bias, large SE and SD, and poor CP are highlighted in boldface.

From the simulation studies, we conclude that the NI-MLIRT models provide results comparable to the MLIRT model when the random errors of the continuous responses follow normal distributions, while it provides more accurate estimates for response-specific parameters and more efficient estimates for other parameters than the MLIRT model when some continuous response variable has outliers.

5. Application to the ELLDOPA study

In this section, we apply the proposed method and the Bayesian inference framework to the motivating ELLDOPA study. For all the results in this section, we use three parallel MCMC chains with overdispersed initial values, and run each chain for 50, 000 iterations. The first 45, 000 iterations are discarded as burn-in and the inference is based on the remaining 5, 000 iterations from each chain.

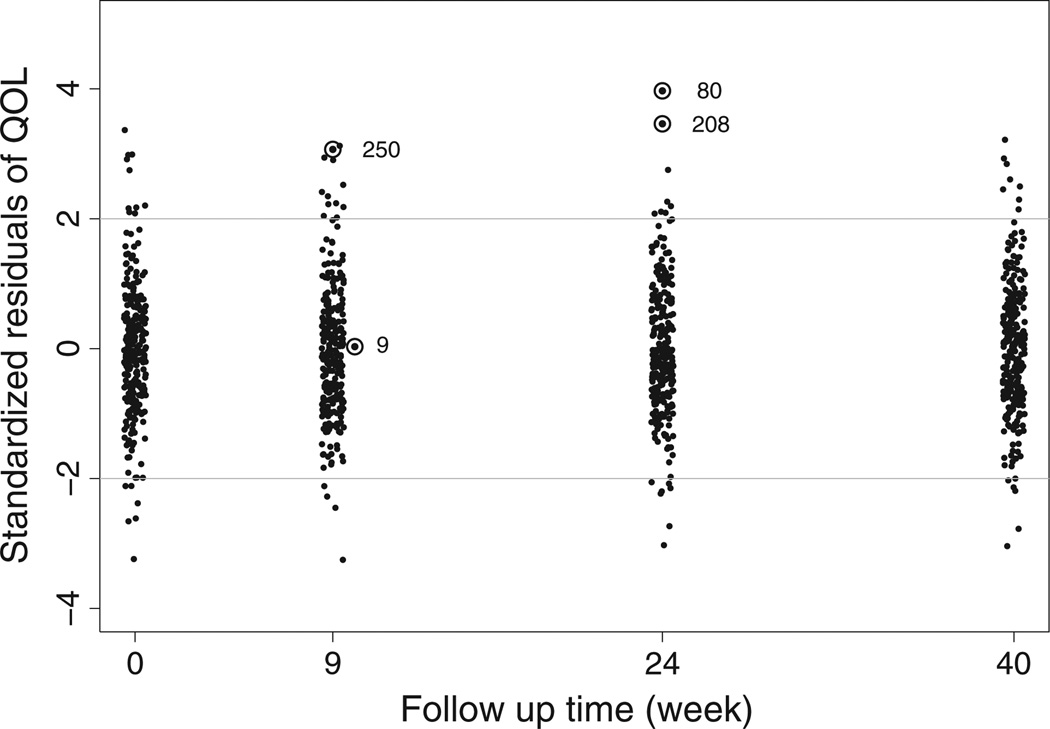

To analyze the ELLDOPA dataset, we let Xi0 = 0 and consider the treatment assignment variable xi (1 treatment, and 0 if placebo) as the only covariate in Xi1. Hence, the level 2 model (4) is θij = ui0+[β10+β11xi+ui1]tij, with visit times being transformed in year tij = (0, 9, 24, 40)/52. We first fit the MLIRT model M1. A plot of the standardized residuals from the response QoL for all patients at each visit (Figure 2) indicates that the normal random error assumption for the response QoL does not fit very well the whole dataset. A few data points have SRs with absolute values larger than 3 (e.g. 3.969 for patient 80 at week 24 visit, 3.462 for patient 208 at week 24 visit, and 3.067 for patient 250 at week 9 visit), indicating potential outliers. In contrast, the SR for patient 9 at week 9 visit is 0.030, indicating a non-outlier. Hence, a heavy-tailed distribution for the response QoL is essential.

Figure 2.

Standardized residuals of the response QoL for all patients at each visit. Numbers 9, 80, 208, and 250 denote four patients.

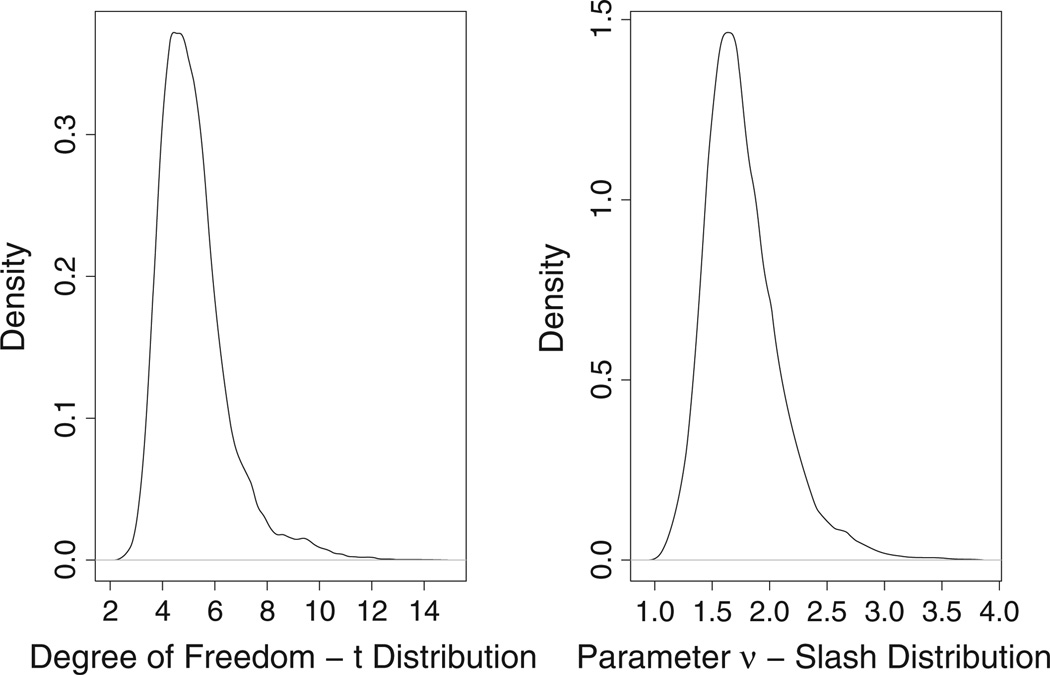

We then apply three NI-MLIRT models (models M2, M3, and M4) to the response QoL. As pointed out in Section 3.2, the normal distribution is a special case of the NI distributions when the tuning parameter ν is large. In practice, the small estimate of ν is an indication of heavy-tailed distribution. Figure 3 displays the posterior density distributions of the degree of freedom of student’s t distribution in model M3 and the tuning parameter ν of the slash distribution in Model M4. For both models, the densities are concentrated around small value (mean: 5.193, 95% CI: [3.386, 8.866] for student’s t distribution; mean: 1.767, 95% CI: [1.267, 2.597] for the slash distribution) providing some evidence against the adequacy of the normality assumption made for the response QoL.

Figure 3.

Posterior densities of the degree-of-freedom of student’s t distribution and the tuning parameter ν of the slash distribution when applying the NI distributions to the response QoL.

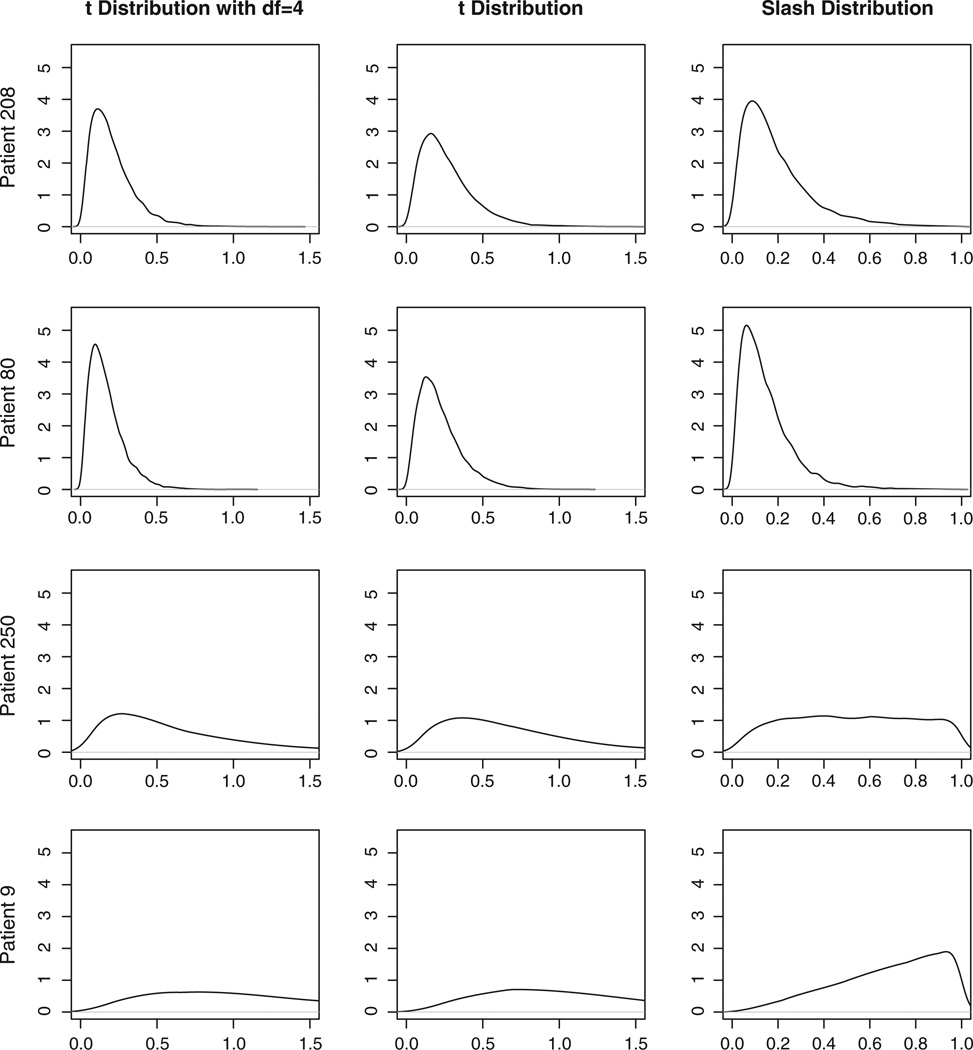

The weight variable wijk in the NI distributions can be used for outlier detection [34]. In Figure 4, the posterior distributions of the weight variable (wijk) are presented for some target patients at certain visits. Patient 208’s and patient 80’s QoL observations at week 24 visit are potential outliers indicated by Figure 2. Their posterior distributions of the weights are sharp with majority of the density close to zero. For patient 250 at week 9 visit, a potential outliers, the posterior distribution of weight is less sharp in two student’s t distributions (models M2 and M3) and is quite flat in the slash distribution (model M4). This indicates that this observation may not be an outlier because the QoL measurements at other visits are quite large (severe) as well. In contrast, for patient 9 at week 9 visit, a clear non-outlier, the posterior distributions of the weight from all three NI distributions have no density clustering at small values.

Figure 4.

Estimates of the weight variable wijk for some patients from various models.

Table IV compares models M1 with M4 by using the model selection criteria discussed in Section 3.4. All three NI-MLIRT models perform significantly better than model M1 with a larger LPML value and smaller DIC, EAIC, and EBIC values, suggesting the necessity of accounting for the outliers in the response QoL. Model M2 has the best fit with the highest LPML value and the lowest DIC, EAIC, and EBIC values. Model M2 provides better fit than model M3, because the fixed value of ν at 4 in model M2 is relatively close to the estimate of ν (mean: 5.193 and 95% CI: [3.386, 8.866]) from model M3. The more parsimonious model M2 provides better fit in this scenario. Table IV compares the posterior mean, SD, 95% equal-tail CIs from various models. The results from all three NI-MLIRT models are very close to each other. In contrast, Model M1 tends to give larger parameter estimates (especially β10 and β11) and it is less precise with larger SDs and wider CIs, a phenomena also reported in Rosa et al. [34] and Lachos et al [23].

Table IV.

Results of fitting the MLIRT model M1, three NI-MLIRT models (M2, M3, and M4) to the response QoL. Parameters ak and bk for k = 1, 2, 3 are the outcome-specific parameters of the responses QoL, unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS), and fatigue, respectively. Parameters a41,…,a45 and b4 are the outcome-specific parameters of the response SEADL.

| Criterion | Model M1 | Model M2 | Model M3 | Model M4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPML | −14227.0 | −14145.4 | −14165.4 | −14171.7 | ||||||||

| DIC | 28248.0 | 28063.7 | 28083.2 | 28076.7 | ||||||||

| EAIC | 28001.5 | 27651.5 | 27702.1 | 27760.7 | ||||||||

| EBIC | 28070.0 | 27719.9 | 27774.1 | 27832.7 | ||||||||

| Parameters | MeanSD | 95% CI | MeanSD | 95% CI | MeanSD | 95% CI | MeanSD | 95% CI | ||||

| a1 | 25.2910.645 | 24.070 | 26.630 | 25.0520.596 | 23.900 | 26.210 | 25.1530.626 | 23.870 | 26.360 | 25.0590.635 | 23.810 | 26.290 |

| b1 | 9.6050.473 | 8.734 | 10.570 | 9.7750.475 | 8.862 | 10.770 | 9.7440.485 | 8.823 | 10.700 | 9.8280.497 | 8.898 | 10.870 |

| a2 | 24.9140.515 | 23.930 | 25.950 | 24.9320.477 | 24.010 | 25.850 | 24.9880.490 | 24.020 | 25.940 | 24.9070.499 | 23.910 | 25.870 |

| b2 | 6.4180.438 | 5.588 | 7.309 | 6.1800.442 | 5.360 | 7.100 | 6.1830.438 | 5.343 | 7.062 | 6.2130.440 | 5.369 | 7.102 |

| a3 | 82.5231.484 | 79.700 | 85.500 | 82.5201.400 | 79.770 | 85.260 | 82.6721.423 | 79.850 | 85.420 | 82.3901.438 | 79.530 | 85.190 |

| b3 | 18.7601.208 | 16.490 | 21.270 | 18.6511.184 | 16.400 | 21.060 | 18.6341.219 | 16.350 | 21.110 | 18.7941.227 | 16.510 | 21.270 |

| a41 | −2.2560.143 | −2.543 | −1.987 | −2.2010.127 | −2.451 | −1.955 | −2.2130.127 | −2.466 | −1.963 | −2.1950.134 | −2.458 | −1.932 |

| a42 | −0.0320.114 | −0.263 | 0.189 | −0.0360.103 | −0.238 | 0.166 | −0.0460.105 | −0.252 | 0.164 | −0.0310.108 | −0.245 | 0.182 |

| a43 | 2.4350.148 | 2.162 | 2.736 | 2.3550.141 | 2.086 | 2.637 | 2.3500.143 | 2.081 | 2.635 | 2.3650.142 | 2.096 | 2.652 |

| a44 | 3.1680.167 | 2.849 | 3.506 | 3.0730.161 | 2.765 | 3.396 | 3.0670.164 | 2.756 | 3.395 | 3.0850.162 | 2.779 | 3.415 |

| a45 | 4.7770.243 | 4.319 | 5.266 | 4.6580.236 | 4.212 | 5.132 | 4.6530.239 | 4.195 | 5.140 | 4.6690.240 | 4.225 | 5.150 |

| b4 | 1.3870.105 | 1.190 | 1.602 | 1.2980.101 | 1.112 | 1.508 | 1.3000.102 | 1.107 | 1.507 | 1.3100.102 | 1.119 | 1.517 |

| β10 | 1.0150.134 | 0.757 | 1.287 | 0.9350.129 | 0.686 | 1.201 | 0.9450.130 | 0.698 | 1.212 | 0.9420.128 | 0.696 | 1.201 |

| β11 | −0.8920.145 | −1.185 | −0.612 | −0.8170.141 | −1.107 | −0.549 | −0.8260.141 | −1.112 | −0.557 | −0.8170.139 | −1.097 | −0.553 |

| ρ | 0.6300.160 | 0.258 | 0.853 | 0.6530.153 | 0.292 | 0.864 | 0.6490.167 | 0.310 | 0.921 | 0.6600.164 | 0.312 | 0.887 |

| σu | 0.2580.058 | 0.160 | 0.379 | 0.2730.061 | 0.172 | 0.419 | 0.2760.062 | 0.179 | 0.428 | 0.2680.059 | 0.164 | 0.398 |

LPML, log pseudo-marginal likelihood; DIC, deviance information criterion; EAIC, expected Akaike information criterion; EBIC, expected Bayesian (or Schwarz) information criterion.

The results from model M2 in Table IV indicate that the placebo patients show significant deterioration across time with the disease progression rate being 0.935 units per year (, 95% CI: [0.686, 1.201]). Although the treatment patients also show significant deterioration across time with disease progression rate being 0.118 units per year (β̂10 + β̂11, 95% CI: [0.006, 0.230]), the treatment significantly slows down the disease progression rate by −0.817 (β̂11, 95% CI: [−1.107,−0.549]) units per year, suggesting the efficacy of the study drug levodopa. To visualize the difference in the disease progression rates in the two groups, Figure 5 displays the posterior estimate of each patient’s subject-specific latent disease severity at each visit. The lowess smooth curves [62] for the placebo and the treatment groups are denoted by the dashed and solid lines, respectively. Figure 5 shows that the placebo patients’ PD severities deteriorate in a much faster rate than the treatment patients as manifested by the departure of two lowess curves, especially at week 40. Figure 5 also reveals one placebo patient (patient 250) who has much worse disease severity than all other patients. This is not surprising because this patient has extremely worse QoL measure as indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 5.

Estimates of the subject-specific disease severity θij at each visit and the lowess smooth curves for the two groups.

To gain further insight into the clinical meanings of the regression parameters β10 and β11, we tabulate in Table V the change from baseline to each follow-up visit for disease severity θij, the responses QoL, UPDRS, and the odds ratio of the cumulative probability at a certain threshold of the response SEADL. At week 9, the placebo patients are expected to increase 0.162 (95% CI: [0.119, 0.208]) units in disease severity, 1.578 (95% CI: [1.180, 1.980]) units in QoL, 0.999 (95% CI: [0.720, 1.295]) units in UPDRS, and are expected to be 0.811 (95% CI: [0.760, 0.860]) as likely to have cumulative probability at a certain threshold of SEADL, whereas the treatment patients are expected to increase 0.020 (95%CI: [0.001, 0.040]) units in disease severity, 0.200 (95% CI: [0.010, 0.385]) units in QoL, 0.126 (95% CI: [0.006, 0.245]) units in UPDRS, and are expected to be 0.974 (95% CI: [0.950, 0.999]) as likely to have cumulative probability at a certain threshold of SEADL. At week 40, the placebo patients are expected to increase 0.719 (95% CI: [0.528, 0.924]) units in disease severity, 7.013 (95% CI: [5.244, 8.798]) units in QoL, 4.439 (95% CI: [3.198, 5.753]) units in UPDRS, and are expected to be 0.398 (95% CI: [0.295, 0.511]) as likely to have cumulative probability at a certain threshold of SEADL, whereas the treatment patients are expected to increase 0.091 (95% CI: [0.004, 0.177]) units in disease severity, 0.887 (95% CI: [0.043, 1.713]) units in QoL, 0.561 (95% CI: [0.027, 1.087]) units in UPDRS, and are expected to be 0.890 (95% CI: [0.795, 0.994]) as likely to have cumulative probability at a certain threshold of SEADL. We omit the results of week 24 and the response fatigue because of space limit, but similar inferences can be made.

Table V.

Change from baseline to each follow-up visit for disease severity θij, responses QoL, unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS), and the odds ratio (OR) of the cumulative probability at a certain threshold of Schwab and England activities of daily living (SEADL). The number in the subscript is the standard deviation (SD). The numbers within the square brackets are 95% equal-tailed CI.

| θij | QoL | UPDRS | OR{p(SEADL ≤ l)} | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Treatment | Placebo | Treatment | Placebo | Treatment | Placebo | Treatment | |

| Week 9 | 0.1620.022 [0.119, 0.208] | 0.0200.010 [0.001, 0.040] | 1.5780.201 [1.180, 1.980] | 0.2000.097 [0.010, 0.385] | 0.9990.146 [0.720, 1.295] | 0.1260.062 [0.006, 0.245] | 0.8110.025 [0.760, 0.860] | 0.9740.013 [0.950, 0.999] |

| Week 24 | 0.4320.060 [0.317, 0.554] | 0.0550.026 [0.003, 0.106] | 4.2080.537 [3.146, 5.279] | 0.5320.258 [0.026, 1.028] | 2.6640.390 [1.919, 3.452] | 0.3370.164 [0.016, 0.652] | 0.5740.048 [0.481, 0.668] | 0.9320.032 [0.871, 0.997] |

| Week 40 | 0.7190.099 [0.528, 0.924] | 0.0910.044 [0.004, 0.177] | 7.0130.895 [5.244, 8.798] | 0.8870.429 [0.043, 1.713] | 4.4390.650 [3.198, 5.753] | 0.5610.274 [0.027, 1.087] | 0.3980.055 [0.295, 0.511] | 0.8900.051 [0.795, 0.994] |

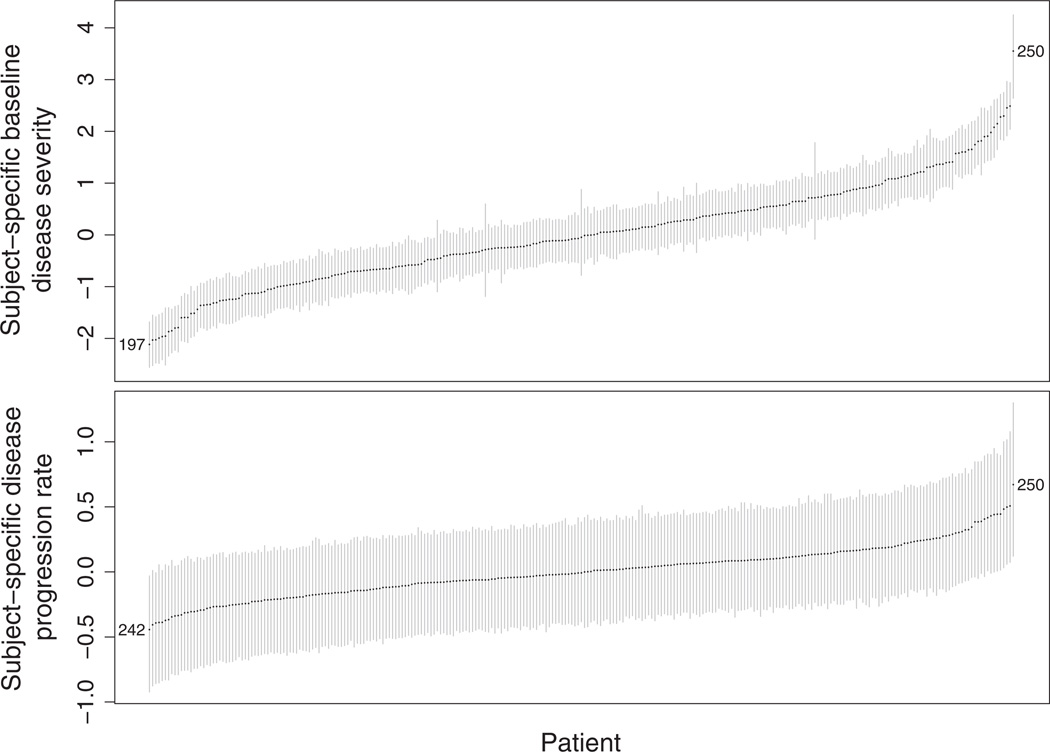

In Table IV, we present the SE (σu) of the random intercept ui1. The estimate of σu from model M2 (mean: 0.273 and 95% CI: [0.172, 0.419]) indicates the existence of subject-specific disease progression rates. The estimate of the correlation coefficient ρ between the random intercept ui0 and the random slope ui1 is 0.653 (95% CI: [0.292, 0.864]). This suggests that patients whose baseline level of disease severity is worse than that of the average population have a disease progression rate faster than the average and vice versa. To gain further insight into ui0, ui1, and ρ, we plot in Figure 6 the rankings of patients’ subject-specific baseline disease severity ui0 (upper panel) and disease progression rate ui1 (lower panel). Each patient is ordered by his or her rank: patients at the bottom left corner show milder baseline disease severity (higher rank) and slower disease progression rate (higher rank), whereas patients at the upper right corner have poorer baseline disease severity (lower rank) and faster disease progression rate (lower rank). To visualize the effect of high correlation coefficient ρ, we have selected three patients as examples. Patient 250 has the worst baseline disease severity and the fastest disease progression rate. In contrast, patient 197 has the mildest baseline disease severity and he/she ranks No. 6 in disease progression rate. Patient 242 has the slowest disease progression rate while he/she ranks No. 4 in baseline disease severity.

Figure 6.

The ranking of subject-specific baseline disease severity (upper panel) and disease progression rate (lower panel) with point estimates and 95% CI. The numbers in the figures are patient numbers.

6. Discussion

In this article, we propose a robust model for MLIRTs, in which the robustness against potential outliers in the continuous measurements is achieved by replacing the normal random error distributions by the heavy-tailed normal/independent family of distributions in the common factor submodel. Our simulation studies show that the proposed NI-MLIRT models improve the accuracy of the response-specific parameter estimates and the efficiency of other parameters when outliers exist. On the other hand, the NI-MLIRT models provide comparable results to the MLIRT model when no outliers exist. We apply the proposed method to the motivating Parkinson’s disease clinical trial ELLDOPA study and illustrate how the normal/independent distributions can be used to evaluate normality assumption to identify outliers and to obtain more robust inference. We provide subject-specific disease severity estimates for all patients at each visit and the figure to visualize the different disease progression rates in the placebo and treatment groups. We give additional insight into the subject-specific baseline disease severity and disease progression rate and their correlation. The proposed models can be fitted using standard available software packages such as R and WinBUGS and can be easily accessible to, modified and extended by practitioners. Please refer to the web-based supporting information‡; for the code written in BUGS language.

Our modeling framework provides great modeling flexibility. For example, a majority of contemporary clinical trials are based on multiple centers or clinics in different geographical locations. The patients recruited by the same center are expected to be correlated, because they are likely to share some common factors, for example, environmental factors. This within-center correlation can be accounted for by adding some center-specific random effects into model (4). Moreover, model (4) assumes linear trend in time. This assumption can be relaxed by adding higher-order terms of time to model the nonlinear disease progression rate.

Our proposed model has some limitations that we view as future research directions. We have assumed that there is a single (unidimensional) latent variable θij so that all outcomes measure the underlying disease severity. However, there may be multiple latent variables representing multidimensional (e.g. sensoria, functions, and cognition) impairment caused by PD. Expanding the unidimensional MLIRT model to the multidimensional one is an interesting direction for future research. Note that the discrimination parameter bk in the MLIRT model controls both within-subject correlation in different outcomes and outcome-specific treatment effect β expressed in model (4). If there is low within-subject correlation but a large treatment effect, this model may underestimate the treatment effect and overestimate the correlation [63]. Furthermore, the proposed model does not consider skewness in the continuous responses. However, features of non-normality might be attributed to both skewness and heavy tails. Methods to combine these within a unified framework for the MLIRT models are currently under investigation. Relaxing the normality assumption for the random effects in the MLIRT models using the NI distributions is also part of our future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by two National Institute of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants U01NS043127 and U01NS43128. The authors are grateful to Dr. Barbara C. Tilley, Jordan J. Elm, Adriana Perez, and Ms. Bo He for helpful discussions and comments. Junsheng Ma is supported by the NIH grant 2T32GM074902-06 and by the Lorne C. Bain Endowment.

Footnotes

Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Fahn S, Oakes D, Shoulson I, Kieburtz K, Rudolph A, Lang A, Olanow C, Tanner C, Marek K Parkinson Study Group. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(24):2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guimaraes P, Kieburtz K, Goetz C, Elm J, Palesch Y, Huang P, Ravina B, Tanner C, Tilley B. Non-linearity of Parkinson’s disease progression: implications for sample size calculations in clinical trials. Clinical Trials. 2005;2(6):509–518. doi: 10.1191/1740774505cn125oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien L, Fitzmaurice G. Analysis of longitudinal multiple-source binary data using generalized estimating equations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2004;53(1):177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams R, Wilson M, Wu M. Multilevel item response models: an approach to errors in variables regression. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1997;22(1):47–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson T. An Introduction to Multivariate Statistical Analysis. 3rd edn. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen E. Latent regression analysis based on the rating scale model. Psychology Science. 2004;46:209–226. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen K, Bjorner J, Kreiner S, Petersen J. Latent regression in loglinear Rasch models. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 2004;33(6):1295–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mislevy R. Estimation of latent group effects. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1985;80:993–997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwinderman A. A generalized Rasch model for manifest predictors. Psychometrika. 1991;56(4):589–600. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maier K. A Rasch hierarchical measurement model. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2001;26(3):307–330. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamata A. Item analysis by the hierarchical generalized linear model. Journal of Educational Measurement. 2001;38(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox J. Multilevel IRT using dichotomous and polytomous response data. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2005;58(1):145–172. doi: 10.1348/000711005X38951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rijmen F, Tuerlinckx F, De Boeck P, Kuppens P. A nonlinear mixed model framework for item response theory. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(2):185. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox J, Glas C. Bayesian estimation of a multilevel IRT model using Gibbs sampling. Psychometrika. 2001;66(2):271–288. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox J. Applications of multilevel IRT modeling. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2004;15(3–4):261–280. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox J. Multilevel IRT modeling in practice with the package mlirt. Journal of Statistical Software. 2007;20(5):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox J. Bayesian Item Response Modeling: Theory and Applications. New York, New York: Springer Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natesan P, Limbers C, Varni J. Bayesian estimation of graded response multilevel models using Gibbs sampling: Formulation and illustration. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2010;70(3):420–439. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung L, Wang W. The generalized multilevel facets model for longitudinal data. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2012;37:231–255. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Linden W, Hambleton R. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. New York, New York: Springer Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lord F, Novick M, Birnbaum A. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinheiro J, Liu C, Wu Y. Efficient algorithms for robust estimation in linear mixed-effects models using the multivariate t distribution. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2001;10(2):249–276. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachos V, Bandyopadhyay D, Dey D. Linear and nonlinear mixed-effects models for censored HIV viral loads using normal/independent distributions. Biometrics. 2011;67:1594–1604. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mislevy R, Bock R. Biweight estimates of latent ability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1982;42(3):725–737. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuster C, Yuan K. Robust estimation of latent ability in item response models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2011;36(6):720–735. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pison G, Rousseeuw P, Filzmoser P, Croux C. Robust factor analysis. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 2003;84(1):145–172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salibian-Barrera M, Van Aelst S, Willems G. Principal components analysis based on multivariate MM estimators with fast and robust bootstrap. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2006;101(475):1198–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert M, Van Driessen K. Fast and robust discriminant analysis. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2004;45(2):301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C. Bayesian robust multivariate linear regression with incomplete data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:1219–1227. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange K, Sinsheimer J. Normal/independent distributions and their applications in robust regression. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1993;2:175–198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutradhar B, Ali M. Estimation of the parameters of a regression model with a multivariate t error variable. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 1986;15(2):429–450. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange K, Little R, Taylor J. Robust statistical modeling using the t distribution. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989:881–896. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lachos V, Bandyopadhyay D, Garay A. Heteroscedastic nonlinear regression models based on scale mixtures of skew-normal distributions. Statistics and Probability Letters. 2011;81:1208–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.spl.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosa G, Padovani C, Gianola D. Robust linear mixed models with normal/independent distributions and Bayesian MCMC implementation. Biometrical Journal. 2003;45(5):573–590. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin T, Lee J. A robust approach to t linear mixed models applied to multiple sclerosis data. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25(8):1397–1412. doi: 10.1002/sim.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin T, Lee J. Bayesian analysis of hierarchical linear mixed modeling using the multivariate t distribution. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2007;137(2):484–495. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho H, Lin T. Robust linear mixed models using the skew t distribution with application to schizophrenia data. Biometrical Journal. 2010;52(4):449–469. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200900184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo C, Paula G, Aoki R. Influence diagnostics in nonlinear mixed-effects elliptical models. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2009;53(12):4143–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meza C, Osorio F, De la Cruz R. Estimation in nonlinear mixed-effects models using heavy-tailed distributions. Statistics and Computing. 2012;22:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N, Elashoff R, Li G. Robust joint modeling of longitudinal measurements and competing risks failure time data. Biometrical Journal. 2009;51(1):19–30. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang X, Li G, Elashoff R. A joint model of longitudinal and competing risks survival data with heterogeneous random effects and outlying longitudinal measurements. Statistics and Its Interface. 2010;3(2):185. doi: 10.4310/sii.2010.v3.n2.a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S, Xia Y. A robust Bayesian approach for structural equation models with missing data. Psychometrika. 2008;73(3):343–364. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abanto-Valle C, Bandyopadhyay D, Lachos V, Enriquez I. Robust Bayesian analysis of heavy-tailed stochastic volatility models using scale mixtures of normal distributions. Computational statistics and data analysis. 2010;54(12):2883–2898. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abanto-Valle C, Migon H, Lachos V. Stochastic volatility in mean models with scale mixtures of normal distributions and correlated errors: a Bayesian approach. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2011;141(5):1875–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osorio F, Paula G, Galea M. On estimation and influence diagnostics for the Grubbs’ model under heavy-tailed distributions. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2009;53(4):1249–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghosh P, Bayes C, Lachos V. A robust Bayesian approach to null intercept measurement error model with application to dental data. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2009;53(4):1066–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lachos V, Angolini T, Abanto-Valle C. On estimation and local influence analysis for measurement errors models under heavy-tailed distributions. Statistical Papers. 2011;52(3):567–590. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao C, Lin J, Zhu X. On estimation of a heteroscedastic measurement error model under heavy-tailed distributions. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2012;56:438–448. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrag A. Quality of life and depression in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;248(1):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schifitto G, Friedman J, Oakes D, Shulman L, Comella C, Marek K, Fahn S The Parkinson Study Group ELLDOPA. Fatigue in levodopa-naive subjects with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;71(7):481–485. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324862.29733.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwab R, England A. Third Symposium on Parkinson’s Disease. Edinburgh: Livingstone; 1969. Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson’s disease; pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lord F. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samejima F. Graded Response Model. New York, New York: Springer; 1997. chap. 5; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curtis S. BUGS code for item response theory. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010 Aug;36:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrews D, Mallows C. Scale mixtures of normal distributions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1974;36:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gelman A, Carlin J, Stern H, Rubin D. Bayesian Data Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geisser S. Predictive Inference: An Introduction. Vol. 55 Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dey D, Chen M, Chang H. Bayesian approach for nonlinear random effects models. Biometrics. 1997;53:1239–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sinha D, Dey D. Semiparametric Bayesian analysis of survival data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:1195–1212. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlin B, Louis T. Bayesian Methods for Data Analysis. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spiegelhalter D, Best N, Carlin B, Van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B:Statistical Methodology. 2002;64(4):583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cleveland W. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American statistical association. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dunson D. Bayesian methods for latent trait modelling of longitudinal data. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2007;16(5):399. doi: 10.1177/0962280206075309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.