Abstract

Objectives

To analyse and compare the determinants of screening uptake for different National Health Service (NHS) health check-ups in the UK.

Design

Individual-level analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys with balanced panel data.

Setting

The UK.

Participants

Individuals taking part in the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), 1992–2008.

Outcome measure

Uptake of NHS health check-ups for cervical cancer screening, breast cancer screening, blood pressure checks, cholesterol tests, dental screening and eyesight tests.

Methods

Dynamic panel data models (random effects panel probit with initial conditions).

Results

Having had a health check-up 1 year before, and previously in accordance with the recommended schedule, was associated with higher uptake of health check-ups. Individuals who visited a general practitioner (GP) had a significantly higher uptake in 5 of the 6 health check-ups. Uptake was highest in the recommended age group for breast and cervical cancer screening. For all health check-ups, age had a non-linear relationship. Lower self-rated health status was associated with increased uptake of blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests; smoking was associated with decreased uptake of 4 health check-ups. The effects of socioeconomic variables differed for the different health check-ups. Ethnicity did not have a significant influence on any health check-up. Permanent household income had an influence only on eyesight tests and dental screening.

Conclusions

Common determinants for having health check-ups are age, screening history and a GP visit. Policy interventions to increase uptake should consider the central role of the GP in promoting screening examinations and in preserving a high level of uptake. Possible economic barriers to access for prevention exist for dental screening and eyesight tests, and could be a target for policy intervention.

Trial registration

This observational study was not registered.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study used consistent individual-level repeated cross-sectional data from a panel survey over a period of 17 years for the different health check-ups.

Our estimation used a balanced panel which also considered attrition effects.

Medical information about results from previous screening examinations was not available, and linking with other data sources could improve our analysis.

Introduction

Individuals are offered different health check-ups in the National Health Service (NHS). These include breast cancer screening, cervical cancer screening, blood pressure checks, cholesterol tests, dental check-ups and eyesight tests. There is no charge for the health check-ups, other than for dental check-ups and eyesight tests. Taking part in health check-ups is important, because screening examinations promote early detection of diseases and are potentially cost saving. There are only few national and international analyses that analyse how different health check-ups are affected by socioeconomic determinants, and typically such studies have been cross-sectional surveys.1 2 One analysis using the UK data has shown that the socioeconomic determinants of breast and cervical cancer screening differ. Our analysis compares for the first time the determinants of six different NHS health check-ups and has a focus on health-related variables such as the role of the general practitioner (GP), existing health problems and health status for these six different health check-ups. Can certain determinants explain the uptake of these six health check-ups, and especially what is the influence of health-related variables on the uptake? In the next sections, the institutional regulations of the six different health check-ups are introduced with a motivation of this analysis, followed by the theoretical framework for our analysis and a discussion of relevant previous empirical prevention research which is related to our own work. The next two sections present own results for the six different health check-ups and discuss these results with possible policy implications.

For each health check-up, a detailed recommendation exists on how often an individual should attend a specific health check-up depending on age limits, risk factors, comorbidities and previous health check-ups. There are differences in invitation policy for different parts of the UK for cervical cancer screening, and for dental screening and the eyesight test an individual has to pay a charge with certain exemption. Table 1 gives the institutional regulations and recommendations for the different health check-ups in the UK.

Table 1.

Regulations and recommendations for the different health check-ups in the UK

| Health check-up | Breast cancer screening | Cervical cancer screening | Blood pressure check | Cholesterol test | Dental screening | Eyesight test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National NHS programme | Yes (NHSBSP) | Yes (NHSCSP) | No | No | No | No |

| Age limits | Until 2002: women between age 50 and 64 After 2002: extension to women between age 65 and 70 |

20–64 (dependent from country and year in the UK) | Recommended for adults aged over 20 | Recommended for adults aged over 20 | Recommended for every individual without age limits | Recommended especially for individuals aged 60 years and older or earlier with risk factors or close relatives with eye disease |

| Recommended time interval between screening examinations | 3-year period | Age 20–64 until 2003 in England: 3–5-year period with majority of Primary Care Trusts followed a 3-year invitation policy Age 25–49 after 2003 in England: 3-year period Age 50–64 after 2003 in England: 5-year period in England |

At least every 5 years without risk factors/comorbidities At least every 1 year with risk factors and older patients Several times per year for individuals with hypertension |

At least every 5 years without risk factors At least every 1–2 years with risk factors Several times per year for individuals with hypercholesterolaemia |

Until 2004: every 6 months independent from the current dental status After 2004: at least one dental screening every 2 years, unless the dentist recommends a different interval based on the patient's current dental status |

Recommended every 2 years, or more frequently with risk factors |

| Differences in invitation policy for different parts of the UK | No | Yes Age of first invitation: age 20 in Scotland, Wales until 2003: age 20 in England after 2003: age 25 in England Invitation period policy: 3-year period between age 20 and 60 in Scotland 3-year period between age 20 and 64 in Wales |

No | No | No | No |

| Risk factors/comorbidities for screening examinations | Close female relatives with a history of breast cancer | Close female relatives with a history of cervical cancer | Overweight, obesity, diabetes, family history of high blood pressure, smoking and lack of exercise | Overweight, obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, family history of early cardiovascular disease or familial hypercholesterolaemia | No | Selected diseases predisposing to eye disorders, for example diabetes or glaucoma |

| Charge from the patient | No | No | No | No | Yes Free for those under the age of 18 or on income support Since 2006: free for all individuals in Scotland and for all individuals under age 25 and age 60 or over in Wales |

Yes Free for individuals age 60 and older, registered blind or partially sighted individuals, or with diabetes or glaucoma Since 2006: free in Scotland |

NHS, National Health Service; NHSBSP, NHS Breast Screening Programme; NHSCSP, NHS Cervical Screening Programme.

The national NHS Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) offers mammography to women at a 3-yearly period.3 Women between age 50 and 64 are invited, and there has been an extension after 2002 of the age range for these programme and women between age 65 and 70 years are also invited. The national NHS Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) offers women a smear test at different time intervals depending on age.4 The age for the first invitation, the age of the last invitation and time periods between invitations for cervical cancer screening are dependent on the country in the UK.5 The age of first invitation is 25 in England6 after 2003, and an age of 20 in Scotland,7 Wales8 and in England until 2003. Between the age of the first invitation and 49 is a 3-yearly recall period in all parts of the UK since 2003, and before 2003, there was a 3–5-yearly recall period policy in England depending on the Primary Care Trust, with the majority of Primary Care Trusts in England following a 3-year policy.9 The policy of a uniform 3-yearly recall period for women between age and 25–49 was implemented after a recommendation by Cancer Research UK, because a 3-year recall policy seemed most effective after analysis of the UK data.10 No information was available for us how quickly each Primary Care Trust in England implemented the changes to the recall policy. Between age 50 and age of the last invitation, cervical cancer screening is offered to women every 3 years until age 60 in Scotland and until age 64 in Wales and every 5 years in England until age 64 after 2003. Women above the age limits are excluded from the recall system and no longer invited unless they need ongoing surveillance or follow-up, for example, because of an abnormal result in any of the three most recent tests. For breast and cervical cancer screening examination, there are sent out routine periodic invitations to women by their GP. Blood pressure can be checked by a GP or another healthcare professional, and it is recommended that adults aged over 20 are checked at least every 5 years11 and the recommendations for regular blood pressure are dependent on age, health status and existing diseases, health behaviours and lifestyle. For older individuals and individuals with risk factors such as overweight, obesity, diabetes, family history of high blood pressure and smoking should be checked every year and for individuals with existing hypertension it should be checked several times a year.12 A cholesterol test is recommended for adults with no symptoms to take place every 5 years starting at age 20.13 14 For all individuals who are overweight or obese and have high blood pressure or diabetes or who have been diagnosed with coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease or who have a family history of early cardiovascular disease or a close family member with a cholesterol-related condition, such as familial hypercholesterolaemia it is recommended to do it every 1–2 years. The cholesterol test is implemented as an invitational programme. For dental screening, the national guidelines recommend at least one check-up every 2 years, unless the dentist recommends a different interval based on the patient's current dental health.15 The national guidelines changed in 2004, the previous recommendation being every 6 months. Dental screening incurs a charge to the patient, and is only free for those under the age of 18 or on income support. Dental screening has been free in Scotland since 200616 and in Wales it is free for individuals under age 25 and aged 60 or over since 2006.17 An eyesight test is recommended every 2 years, or more frequently if necessary.18 It is especially advised for individuals aged 60 years and older, individuals from certain ethnic groups, for example, Afro-Caribbeans, and for those with selected diseases predisposing to eye disorders, for example, diabetes, glaucoma or close relatives with eye disease. There is a charge for the eyesight test, but it is free for individuals aged 60 and older, or who are blind or partially sighted, or who have diabetes or glaucoma. Eyesight tests have been free in Scotland since 2006.19 For dental screening and eyesight tests, the individual dental or optometry practices can decide on sending invitation letters.

Theoretical approach

Economic models of the demand of healthcare in general, and preventative care in particular, are based on human capital models.20 This framework has also been used for the modelling of demand for primary and secondary prevention.21 These categories of prevention are self-protection measures that improve early detection and health outcomes.22 The problem with economic models of prevention is that two important aspects are typically not considered at the same time in detail: the distinction between acute and preventative care and uncertainty. Some dynamic economic models for the demand of healthcare take only uncertainty into consideration; no distinction being made between acute and preventative care.23 Acute care describes the consumption aspect of health whereas preventative care describes the investment aspect. The (simplified) Grossman model makes the distinction between acute and preventative care, but uncertainty is not considered in this model.24 Only one economic model explicitly considers both the demands for preventative healthcare, using a stochastic dynamic framework.25 However, in this article, no non-economic factors were considered. Our conceptual framework is based on a human capital approach, and, as an extension, non-economic factors such as non-monetary barriers are included. Our approach is also supported by previous research which has investigated determinants of different types of screening examinations.26

Participation in breast or cervical cancer screening examinations in past periods has predictive value for the uptake in the actual period, that is, the past screening behaviour is correlated with the current behaviour.27 28 Age can have different effects on the demand for prevention.29 30 For breast and cervical cancer screening examinations, medical guidelines exist with explicit recommendations on how often screening should be carried out in certain time intervals, and for the recommended age intervals uptake should be higher than for non-recommended age intervals. However, on one hand, according to the Grossman model, health depreciates at an increasing rate at older ages, and the necessity to maintain health increases and, as a consequence, the demand for preventive activities increases. On the other hand, older individuals have a shorter life span and pay-off period for their investment in prevention activities. Therefore, the effect of increasing age on uptake cannot be predicted with confidence. Empirical studies often find a negative relationship between age and uptake of health check-ups.30 31 The studies which analysed possible gender differences in the utilisation of healthcare services found that women have a higher utilisation of healthcare services32 and also a higher use of preventative services including blood pressure checks, cholesterol tests and dental screening.33 34 Higher educational level may be expected to lead to an increase in the demand for prevention services, because individuals with a higher education may have higher efficiency in the production of health and also increased self-efficacy, higher confidence and motivation.21 27 30 31 Individuals who live in a partnership have a higher propensity for screening examinations, and living in a partnership may be a proxy for having a more dense social support network that encourages individuals to take part in prevention activities and some empirical studies have confirmed this hypothesis.35–37 A higher number of children in the household can influence screening behaviour through time constraints.27 38 Household income may be expected to lead to an increase in the demand for prevention services, because higher income leads to an increase in demand for time in perfect health.20 24 In some studies, increasing household income increased uptake of preventive care,29 30 39 although the effect may be weaker in the UK compared with other countries, because most preventative services are free in the UK. Employment was added as a further control variable, because individuals who work may have higher opportunity costs in comparison with unemployed and retired individuals. In a systematic review of the influence of different determinants on the uptake of health check-ups, influence of employment for the uptake of different health check-ups was found to be inconsistent.26 40 The GP plays a role as gatekeeper in the UK healthcare system and can give advice and information about the importance of health check-ups for the early detection of diseases, and therefore uptake may be enhanced by previous GP visits.41 42 Cervical cancer screening, blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests can be performed in a GP practice. Poor self-rated health status and existing general health problems could encourage people to think about their health in general and therefore to invest in health and to increase participation in screening examinations, and this seems to be the case for general health check-ups such as blood pressure check and cholesterol test, but not for female-specific cancer screenings such as the mammography and the smear test.29 Psychological factors such as fear and anxiety about receiving a cancer diagnosis may deter some women from attending one of these health check-ups. Furthermore, individuals in a poor health state may not be able to visit the screening location such as the GP, family clinic or mammography unit, the dentist or the optometrist, because of physical limitations. There are contradicting findings on the effect of poor health status on the uptake of health check-ups, with increased uptake of cholesterol checks and a lower uptake of mammograms and Pap smears.43 Smoking can serve as an indicator for the weakened preference of an individual for health in comparison with other goods and smoking individuals show risk-taking behaviour.44 Individuals who smoke have poorer preventative health habits such as a reduced level of physical activity in comparison with non-smoking women.45 The predicted influence of smoking on uptake was empirically confirmed for breast cancer screening with a lower uptake for smoking women.30 For individuals with non-white ethnic origin, cultural barriers may exist, and this is especially the case for breast and cervical cancer screening. In an empirical investigation, ethnicity was the most important predictor for cervical cancer screening, with white British women having a higher uptake than women of other ethnicity. Registration with a GP is a necessary condition for receiving an invitation letter for breast and cervical cancer screening and routine periodic invitations are sent from the GP according to the recommended interval for breast and cervical cancer screening. A changed residence and address of a woman lowers the chance to receive an invitation letter. A lower uptake of cervical cancer screening was found in one study for women in the UK who had changed residence and address,38 but not in another one.27

Information about the uptake of these different health check-ups over a period of nearly 20 years is available in the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). Only one study has compared these different NHS health check-ups from 1991 to 2003.46 However, this study did not analyse the influence of health-related and socioeconomic characteristics on the uptake. Random effect (RE) panel probit models were only with unbalanced panels, with the potential problem of attrition bias, and as a consequence selection bias in the estimates can occur.47 Therefore, our analysis compares how past screening behaviour, individual and household characteristics, transitory and permanent household income affect uptake of these different health check-ups.

Methods

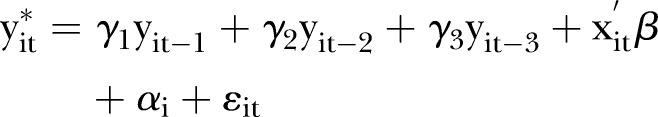

It is sensible for our estimation to consider how screening behaviour was in the past time and the recommended time interval for a screening examination (eg, for breast and cervical cancer screening examinations the recommended 3-year intervals), because there is an increased likelihood of participating in a screening examination after the recommended time interval. In addition, there exists the possibility that screening examinations are recommended in shorter time intervals if an individual belongs to a high-risk population such as in the female cancer screening examinations with close relatives having a history of breast or cervical cancer. Also there exists for all the different health check-ups the possibility that an inconclusive check-up in the actual year has a consequence a control follow check-up in the next year. With the BHPS it is not possible to differentiate between routine check-ups according to the screening guidelines or as a response to an inconclusive result from a health check-up in the previous year or as an advice to do a health check-up from a GP. To include these different possibilities for the analysis of uptake behaviour, a dynamic specification with lags for the past 3 years was chosen for the different health check-ups. To model the dynamic nature of screening examinations and because uptake is a binary variable, a dynamic REs panel probit model was used to estimate the uptake of NHS health check-ups over the panel period from 1992 to 2008. The advantage of such a specification is that the uptake of health check-ups is explained not only by individual and household characteristics, but also by the past screening behaviour and, therefore, persistence in screening behaviour (state dependence). A further advantage of this econometric specification which uses panel data and not cross-sectional data is that individual heterogeneity and state dependence can be considered in a dynamic panel data model, which is not possible in a model for cross-sectional data. One possibility for estimating a dynamic REs panel probit is the Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator that specifies a relationship between the unobserved time-invariant individual effect and the observed characteristics and initial conditions,48 and the econometric model is given by the following three equations (1)–(3).

|

1 |

In the first equation  indicates the unobserved latent variable of an individual i at a given time t for taking part in a specific screening examination, yit−1, yit−2 and yit−3 are the screening examination decisions of the individual i 1, 2 and 3 periods before t and γ1, γ2, γ3 are the related coefficients for these variables, x is a vector of time variant and time invariant covariates,

indicates the unobserved latent variable of an individual i at a given time t for taking part in a specific screening examination, yit−1, yit−2 and yit−3 are the screening examination decisions of the individual i 1, 2 and 3 periods before t and γ1, γ2, γ3 are the related coefficients for these variables, x is a vector of time variant and time invariant covariates,  is the vector of coefficients associated with these covariates,

is the vector of coefficients associated with these covariates,  is the random error term and

is the random error term and  indicates the individual-specific term for time-invariant unobserved variables which is modelled according to equation (2) as individual-specific RE:

indicates the individual-specific term for time-invariant unobserved variables which is modelled according to equation (2) as individual-specific RE:

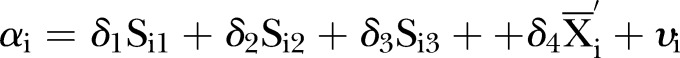

|

2 |

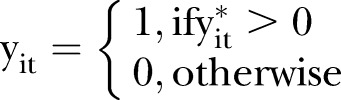

A normal density for the individual-specific RE is assumed and the first three terms are the initial conditions with the uptake of the specific health check-up for an individual i in the first three periods of the panel: Si1, Si2 and Si3.The fourth term allows correlation between the time-varying variables of an individual by including the average  over the whole panel observation period and the individual-specific RE,49 which divides the time-varying variables into a transitory and permanent component for the estimation. νi is the error term assumed normally distributed with zero mean and SD σα. This specification has the advantage that time-invariant unobserved variables which are correlated to time-varying variables are captured by the mean of these variables and give a less biased estimate of the transitory component of these variables. The third equation gives the observed binary outcome yit of taking part in a specific health check-up for individual i in period t.

over the whole panel observation period and the individual-specific RE,49 which divides the time-varying variables into a transitory and permanent component for the estimation. νi is the error term assumed normally distributed with zero mean and SD σα. This specification has the advantage that time-invariant unobserved variables which are correlated to time-varying variables are captured by the mean of these variables and give a less biased estimate of the transitory component of these variables. The third equation gives the observed binary outcome yit of taking part in a specific health check-up for individual i in period t.

|

3 |

The chosen Mundlak-Wooldridge specification has the advantage that, under certain assumptions, the bias which is caused by the persistence of screening behaviour is removed. The crucial assumptions for the estimation of the dynamic RE model are that the relationship between the unobserved time-invariant individual effect and the mean of the observed characteristics is correctly specified and also the distributional assumptions on the initial conditions are correct. The breast cancer screening programme (NHSBSP) and cervical cancer screening programme (NHSCSP) were introduced in 1988 before the beginning of the BHPS and also the four other health check-ups had been available to individuals before the BHPS had started. For our estimation technique, it is assumed that the health check-ups that had been undertaken before the first wave of the BHPS are uncorrelated with the health check-ups recorded in the BHPS. If this assumption is violated, the inclusion of initial conditions of health check-ups for the years 1992–1994 could result in biased estimates for our regressions. An advantage of our statistical approach is that some previous analyses have investigated the uptake of health check-ups with cross-sectional data and, therefore, could not control for unobserved heterogeneity, and other analyses used unbalanced panel data sets for their estimation.27 46 Estimation of unbalanced panels with ad hoc treatments of initial problems has unfavourable estimation properties and could result in biased estimation as has been shown by simulation studies.47 The estimation results of balanced panels (BPs) are more reliable, because BPs satisfy the assumptions of the Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator.50 51 Therefore, estimation of BPs for the different health check-ups was preferred over unbalanced panels. An alternative to the Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator would be the maximum likelihood estimator proposed by Heckman52; however, for BPs with more than 5–8 periods, the finite sample properties of the Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator are better.47

We used the BHPS, which is an annual survey of households in the UK. It is a nationally representative sample of more than 5000 households and individuals aged 16 and over.53 The first wave of the data collection for this survey started in 1991 and all the original individuals were interviewed in each succeeding year unless they dropped out. Questions about taking part in NHS health checks-up have been in every wave from the start of the panel survey in 1991 until 2008. For the analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening, only women were included, for all other types of health check-ups men and women were included. In our analysis and construction of the balanced sample only individuals from England, Wales and Scotland were selected, because data collection started in Northern Ireland from wave 11 and not from the first wave. For the construction of the BP, 17 years of information were used: from 1992 to 2008, because in the first wave only a small number of individuals were interviewed in 1991. For an individual to be included in our analysis, provision of the specific health check-up had to be from the NHS; individuals with private provision or with NHS and private provision for a specific health check-up have been excluded from the analysis. The dependent variable takes the value of 1 in a specific year if the specific health check-up (breast cancer screening, cervical cancer screening, blood pressure check, cholesterol test, dental test and eyesight test) was carried out and 0 if not. For analysing the changes in the medical screening guidelines for three different health check-ups (breast cancer screening, cervical cancer screening and dental screening) a dummy coding was chosen: for breast cancer screening and age group 65–70, all years before and including 2002 were coded with 0 and all the following years with 1; for cervical cancer screening and age group 25–49, all years before and including 2003 were coded with 0 and all the following years with 1; for dental screening, all years before and including 2004 were coded with 0 and all the following years with 1.

The BP included: for breast cancer screening, 861 women with 12 054 observations; for cervical cancer screening, 867 women with 12 138 observations; for blood pressure checks, 1405 individuals with 19 670 observations; for cholesterol tests, 1568 individuals with 21 952 observations; for dental screening, 706 individuals with 9884 observations and for eyesight tests, 613 individuals with 8582 observations. In our analysis, for breast cancer screening, we followed the age groups of the screening guidelines: 16–49 (reference group), 50–64, 65–70 and age 71 and older. For cervical cancer screening we used the age groups of the screening guidelines: 16–19 (reference group), 20–24, 25–49, 50–64 and age 65 and older. For all other screening checks, the following groups were used: 16–39 (reference group), 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and 80 and older. For blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests, we included information on whether the person had diabetes or also heart/blood pressure/blood circulation problems, and for eyesight tests, information on eyesight problems and diabetes was used. Actual (transitory) income was defined as the total equivalised and deflated household annual income divided by 100 and permanent household income was defined as annual household income over the 17 years between 1992 and 2008. Household income was deflated and transformed in per capita income using the modified OECD scale to allow for household size and needs.54 The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) was used for the categorisation of educational levels with tertiary, secondary and primary education (reference category). Health status was self-rated and included in our analysis with categories from excellent (1) as reference category in regressions, good (2), fair (3) and poor (4) to very poor (5).55

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in our estimation for the BPs for the different health check-ups.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics for the balanced panels of different health check-ups in the UK

| Health check-up | Breast cancer screening | Cervical cancer screening | Blood pressure check | Cholesterol test | Dental screening | Eyesight test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health check-up in actual period t | 0.139 | 0.204 | 0.512 | 0.195 | 0.576 | 0.344 |

| Health check-up in 1992 | 0.150 | 0.295 | 0.419 | 0.095 | 0.492 | 0.227 |

| Health check-up in 1993 | 0.144 | 0.296 | 0.421 | 0.112 | 0.506 | 0.238 |

| Health check-up in 1994 | 0.127 | 0.296 | 0.425 | 0.100 | 0.528 | 0.217 |

| Health check-up 1 year before (t−1) | 0.137 | 0.213 | 0.500 | 0.178 | 0.572 | 0.329 |

| Health check-up 2 years before (t−2) | 0.136 | 0.222 | 0.488 | 0.164 | 0.562 | 0.316 |

| Health check-up 3 years before (t−3) | 0.135 | 0.231 | 0.475 | 0.149 | 0.558 | 0.303 |

| HH income (mean/SD) | 3.134/1.857 | 3.124 (1.862) | 3.062 (1.819) | 3.158 (1.900) | 2.856 (1.762) | 2.812 (1.823) |

| Living with partner | 0.727 | 0.732 | 0.760 | 0.768 | 0.735 | 0.735 |

| Number of children in HH (mean/ SD) | 0.531/0.919 | 0.526 (0.916) | 0.540 (0.927) | 0.547 (0.926) | 0.545 (0.948) | 0.601 (0.984) |

| Secondary education (ISCED) | 0.430 | 0.433 | 0.424 | 0.427 | 0.399 | 0.434 |

| Tertiary education (ISCED) | 0.324 | 0.320 | 0.338 | 0.349 | 0.306 | 0.274 |

| Employed | 0.524 | 0.522 | 0.562 | 0.588 | 0.504 | 0.520 |

| GP visit during past 12 months | 0.810 | 0.811 | 0.765 | 0.756 | 0.764 | 0.747 |

| Health status self-rated good | 0.477 | 0.482 | 0.475 | 0.479 | 0.479 | 0.462 |

| Health status self-rated fair | 0.236 | 0.237 | 0.238 | 0.233 | 0.254 | 0.248 |

| Health status self-rated poor | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.070 | 0.068 | 0.083 | 0.080 |

| Health status self-rated very poor | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.023 |

| Smoking | 0.164 | 0.166 | 0.176 | 0.172 | 0.215 | 0.221 |

| Moved residence | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.050 | 0.056 |

| Scotland | 0.080 | 0.078 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.090 | 0.077 |

| Wales | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.045 | 0.064 |

| Ethnic origin non-white | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.015 |

| Age (mean/SD) | 52.51/15.29 | 52.62 (15.27) | 52.35 (15.65) | 51.83 (15.37) | 53.58 (15.67) | 52.08 (15.90) |

| Female sex | 0.593 | 0.567 | 0.575 | 0.544 | ||

| Health problem blood pressure | 0.232 | 0.221 | ||||

| Health problem diabetes | 0.049 | 0.045 | 0.069 | |||

| Health problem sight | 0.049 |

GP, general practitioner; HH, household; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

For the period 1992–2008, there were the following uptake rates within 1 year for individuals for the BP: 13.9% for breast cancer screening, 20.4% for cervical cancer screening, 51.2% for the blood pressure check, 19.5% for the cholesterol test, 57.6% for dental screening and 34.4% for the eyesight test.

Table 3 provides the estimated coefficients for the dynamic REs probit model with initial conditions for the BP for the different health check-ups. For a robustness check of the age categorisation for cervical cancer screening two different possibilities of age categorisation have been selected. Age categorisation is in specification 1: age 16–19 (ref.), 20–24, 25–49, 50–64 and 65+ (sample age ≥16). Age categorisation is in specification 2: age 20–24 (ref.), 25–49, 50–64 and 65+ (sample age ≥20). The estimation results for specifications 1 and 2 with the different age categorisations are very similar for all other variables (see online supplementary technical appendix table 1). We have selected to choose age categorisation as in the specification 1 in the comparison table 3 for the different health check-ups.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates and SEs for the uptake of health check-ups in the UK

| Health check-up | Breast cancer screening | Cervical cancer screening | Blood pressure check | Cholesterol test | Dental screening | Eyesight test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health check-up in 1992 | 0.092 (0.064) | 0.229*** (0.044) | 0.107*** (0.035) | 0.139** (0.055) | 0.488*** (0.079) | 0.373*** (0.065) |

| Health check-up in 1993 | 0.044 (0.065) | 0.195*** (0.045) | 0.102*** (0.036) | 0.115** (0.054) | 0.223*** (0.085) | 0.343*** (0.064) |

| Health check-up in 1994 | 0.175*** (0.066) | 0.142*** (0.047) | 0.202*** (0.037) | 0.233*** (0.054) | 0.591*** (0.089) | 0.290*** (0.067) |

| Averaged HH income | –0.015 (0.026) | 0.008 (0.022) | –0.014 (0.018) | 0.003 (0.019) | 0.134*** (0.037) | 0.068** (0.029) |

| Averaged living with partner | 0.117 (0.135) | 0.017 (0.107) | –0.007 (0.076) | 0.102 (0.090) | –0.115 (0.129) | 0.064 (0.115) |

| Averaged number of children in HH | 0.032 (0.064) | 0.022 (0.046) | 0.012 (0.037) | –0.064 (0.044) | 0.084 (0.068) | 0.063 (0.058) |

| Averaged secondary education (ISCED) | –0.604 (0.423) | –0.169 (0.383) | –0.005 (0.213) | 0.466 (0.323) | –1.691*** (0.453) | –0.244 (0.339) |

| Averaged tertiary education (ISCED) | –0.498 (0.517) | –0.245 (0.427) | 0.030 (0.241) | 0.716** (0.351) | –1.495*** (0.479) | –0.143 (0.371) |

| Average status employed | 0.384*** (0.105) | –0.041 (0.093) | 0.173** (0.075) | 0.152* (0.081) | –0.073 (0.141) | –0.038 (0.117) |

| Averaged GP visit during past 12 months | 0.460*** (0.141) | –0.037 (0.120) | 0.240*** (0.090) | 0.243** (0.098) | 0.587*** (0.164) | 0.840*** (0.143) |

| Averaged health status self-rated good | 0.006 (0.127) | –0.029 (0.107) | –0.086 (0.082) | 0.052 (0.094) | –0.101 (0.174) | –0.118 (0.145) |

| Averaged health status self-rated fair | –0.021 (0.151) | –0.131 (0.136) | –0.217** (0.100) | –0.194* (0.109) | –0.225 (0.200) | –0.303* (0.171) |

| Averaged health status self-rated poor | 0.207 (0.247) | 0.189 (0.235) | –0.293 (0.187) | –0.022 (0.179) | –0.315 (0.313) | –0.306 (0.283) |

| Averaged health status self-rated very poor | –0.353 (0.432) | 0.129 (0.378) | –0.420 (0.333) | 0.078 (0.294) | –0.471 (0.456) | –0.420 (0.438) |

| Averaged status smoking | 0.118 (0.141) | –0.154 (0.118) | 0.188** (0.081) | 0.195** (0.091) | –0.113 (0.128) | –0.042 (0.119) |

| Averaged status moved residence | –0.487 (0.379) | 0.121 (0.293) | –0.003 (0.211) | –0.418* (0.248) | 0.069 (0.427) | 0.021 (0.354) |

| Averaged age | 0.029*** (0.004) | –0.006 (0.004) | –0.016*** (0.003) | –0.030*** (0.003) | –0.006 (0.006) | 0.000 (0.005) |

| Averaged health problems blood pressure | 0.317*** (0.083) | 0.001 (0.075) | ||||

| Averaged health problems diabetes | 0.166 (0.162) | –0.264* (0.144) | –0.254 (0.192) | |||

| Averaged health problems sight | –0.046 (0.232) | |||||

| Health check-up 1 year before (t−1) | 0.115** (0.048) | 0.233*** (0.039) | 0.501*** (0.027) | 0.950*** (0.035) | 1.014*** (0.051) | 0.247*** (0.041) |

| Health check-up 2 years before (t−2) | –0.030 (0.048) | –0.286*** (0.039) | 0.215*** (0.028) | 0.352*** (0.037) | 0.385*** (0.053) | 0.350*** (0.041) |

| Health check-up 3 years before (t−3) | 0.814*** (0.044) | 0.570*** (0.036) | 0.158*** (0.028) | 0.238*** (0.038) | 0.265*** (0.052) | 0.101** (0.041) |

| HH income | 0.006 (0.015) | 0.005 (0.013) | 0.002 (0.010) | 0.009 (0.011) | –0.024 (0.017) | –0.023 (0.016) |

| Living with partner | 0.034 (0.116) | 0.136 (0.086) | 0.065 (0.060) | –0.040 (0.076) | 0.215** (0.097) | –0.061 (0.087) |

| Number of children in HH | –0.135*** (0.048) | –0.001 (0.031) | –0.095*** (0.025) | –0.007 (0.033) | –0.002 (0.042) | –0.008 (0.038) |

| Secondary education (ISCED) | 0.645 (0.418) | 0.180 (0.377) | 0.094 (0.209) | –0.467 (0.319) | 1.715*** (0.445) | 0.247 (0.332) |

| Tertiary education (ISCED) | 0.581 (0.511) | 0.278 (0.419) | 0.115 (0.235) | –0.662* (0.346) | 1.585*** (0.467) | 0.160 (0.360) |

| Employed | –0.205*** (0.065) | 0.055 (0.056) | –0.098** (0.045) | –0.144*** (0.054) | –0.040 (0.078) | –0.094 (0.064) |

| GP visit during past 12 months | 0.169*** (0.058) | 0.419*** (0.048) | 1.036*** (0.034) | 0.664*** (0.046) | 0.096* (0.055) | 0.070 (0.050) |

| Health status self-rated good | 0.075 (0.063) | –0.039 (0.050) | 0.079** (0.038) | 0.046 (0.048) | –0.036 (0.070) | 0.066 (0.061) |

| Health status self-rated fair | 0.031 (0.076) | –0.031 (0.062) | 0.303*** (0.046) | 0.184*** (0.056) | –0.057 (0.081) | 0.140* (0.073) |

| Health status self-rated poor | 0.014 (0.101) | –0.048 (0.089) | 0.505*** (0.066) | 0.288*** (0.072) | –0.156 (0.106) | 0.203** (0.095) |

| Health status self-rated very poor | 0.048 (0.152) | –0.253* (0.144) | 0.669*** (0.122) | 0.448*** (0.111) | 0.262* (0.154) | 0.076 (0.142) |

| Smoking | –0.218* (0.123) | 0.131 (0.100) | –0.251*** (0.067) | –0.184** (0.079) | –0.186* (0.099) | –0.059 (0.093) |

| Moved residence | 0.051 (0.092) | –0.063 (0.070) | 0.146*** (0.051) | 0.023 (0.066) | –0.207** (0.086) | –0.075 (0.081) |

| Scotland | 0.013 (0.088) | 0.028 (0.075) | 0.050 (0.056) | 0.026 (0.059) | 0.046 (0.104) | 0.020 (0.098) |

| Wales | 0.147 (0.098) | –0.129 (0.093) | –0.063 (0.070) | –0.039 (0.070) | –0.114 (0.144) | –0.030 (0.107) |

| Ethnic origin non-white | 0.195 (0.199) | –0.242 (0.188) | 0.143 (0.146) | –.074 (0.146) | –0.207 (0.271) | –0.249 (0.221) |

| Age 50–64 | 0.644*** (0.046) | |||||

| Age 65–70 | –0.645*** (0.093) | |||||

| Age 71 and older | –1.149*** (0.099) | |||||

| Age 20–24 | 0.472*** (0.173) | |||||

| Age 25–49 | 0.327*** (0.087) | |||||

| Age 65 and older | 0.189*** (0.066) | |||||

| Age 40–49 | 0.137*** (0.042) | 0.660*** (0.059) | 0.130 (0.084) | 0.319*** (0.070) | ||

| Age 50–59 | 0.376*** (0.065) | 1.083*** (0.082) | 0.090 (0.129) | 0.454*** (0.104) | ||

| Age 60–69 | 0.608*** (0.086) | 1.544*** (0.107) | 0.014 (0.172) | 0.544*** (0.132) | ||

| Age 70–79 | 0.830*** (0.109) | 1.709*** (0.132) | –0.152 (0.213) | 0.703*** (0.162) | ||

| Age 80 and older | 1.034*** (0.137) | 1.966*** (0.160) | –0.400 (0.267) | 0.718*** (0.197) | ||

| Female sex | 0.094*** (0.033) | –0.152*** (0.034) | 0.100 (0.064) | 0.164*** (0.055) | ||

| Health problem blood pressure | 0.901*** (0.047) | 0.568*** (0.042) | ||||

| Health problem diabetes | 0.446*** (0.118) | 0.847*** (0.104) | 1.095*** (0.126) | |||

| Health problem sight | 0.415*** (0.091) | |||||

| Breast cancer screening policy change | 0.499*** (0.103) | |||||

| Cervical cancer screening policy change | –0.113** (0.045) | |||||

| Dental policy change | 0.068 (0.053) |

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

GP, general practitioner; HH, household; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

For all health check-ups, taking part in past screening examinations showed a strong influence on the current screening examination. The effect of having the same screening examination 1 year ago was strongest for dental screening. The magnitude of the effects, the marginal effects, is shown in table 4, and for dental screening examinations, there was an increase of 18.2% if there has been a visit 1 year before.

Table 4.

Marginal effects and SEs for main predictors of uptake for health check-ups in the UK

| Health check-up | Breast cancer screening | Cervical cancer screening | Blood pressure check | Cholesterol test | Dental screening | Eyesight test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health check-up 1 year before (t−1) | 0.017 (0.007) | 0.051 (0.009) | 0.125 (0.007) | 0.149 (0.006) | 0.182 (0.009) | 0.066 (0.011) |

| Health check-up 2 years before (t−2) | −0.004 (0.007) | −0.065 (0.009) | 0.054 (0.007) | 0.055 (0.006) | 0.070 (0.009) | 0.094 (0.011) |

| Health check-up 3 years before (t−3) | 0.123 (0.007) | 0.126 (0.008) | 0.040 (0.007) | 0.037 (0.006) | 0.047 (0.009) | 0.027 (0.011) |

| HH income | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.006 (0.004) |

| Living with partner | 0.006 (0.018) | 0.028 (0.019) | 0.016 (0.015) | −0.006 (0.012) | 0.038 (0.017) | −0.016 (0.023) |

| Number of children in HH | −0.021 (0.007) | −0.000 (0.007) | −0.024 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.005) | 0.000 (0.008) | −0.002 (0.010) |

| Secondary education (ISCED) | 0.099 (0.064) | 0.040 (0.084) | 0.024 (0.052) | −0.073 (0.050) | 0.305 (0.080) | 0.066 (0.089) |

| Tertiary education (ISCED) | 0.088 (0.079) | 0.053 (0.093) | 0.029 (0.059) | −0.103 (0.054) | 0.283 (0.084) | 0.043 (0.097) |

| Employed | −0.031 (0.010) | 0.013 (0.012) | −0.025 (0.011) | −0.022 (0.009) | −0.010 (0.014) | −0.025 (0.017) |

| GP visit during past 12 months | 0.029 (0.009) | 0.095 (0.011) | 0.259 (0.008) | 0.104 (0.007) | 0.017 (0.010) | 0.019 (0.013) |

| Health status self-rated good | 0.010 (0.010) | −0.009 (0.011) | 0.020 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.008) | −0.006 (0.012) | 0.018 (0.016) |

| Health status self-rated fair | 0.003 (0.012) | −0.008 (0.014) | 0.076 (0.012) | 0.029 (0.009) | −0.012 (0.014) | 0.038 (0.019) |

| Health status self-rated poor | −0.000 (0.015) | −0.012 (0.020) | 0.126 (0.016) | 0.045 (0.011) | −0.033 (0.019) | 0.054 (0.025) |

| Health status self-rated very poor | 0.005 (0.023) | −0.057 (0.032) | 0.167 (0.030) | 0.070 (0.017) | 0.044 (0.028) | 0.020 (0.038) |

| Smoking | −0.033 (0.019) | 0.030 (0.022) | −0.063 (0.017) | −0.029 (0.012) | −0.032 (0.018) | −0.016 (0.025) |

| Moved residence | 0.007 (0.014) | −0.012 (0.015) | 0.036 (0.013) | 0.004 (0.010) | −0.035 (0.015) | −0.020 (0.022) |

| Scotland | 0.002 (0.013) | 0.006 (0.017) | 0.012 (0.014) | 0.004 (0.009) | 0.005 (0.018) | 0.005 (0.026) |

| Wales | 0.024 (0.015) | −0.029 (0.021) | −0.016 (0.017) | −0.006 (0.011) | −0.021 (0.026) | −0.008 (0.029) |

| Ethnic origin non-white | 0.030 (0.031) | −0.055 (0.042) | 0.036 (0.037) | −0.012 (0.023) | −0.036 (0.048) | −0.067 (0.059) |

| Age 50–64 | 0.099 (0.007) | 0.042 (0.015) | ||||

| Age 65–70 | −0.101 (0.014) | |||||

| Age 71 and older | −0.177 (0.015) | |||||

| Age 20–24 | 0.104 (0.039) | |||||

| Age 25–49 | 0.073 (0.019) | |||||

| Age 65 and older | −0.180 (0.019) | |||||

| Age 40–49 | 0.036 (0.011) | 0.070 (0.006) | 0.025 (0.015) | 0.081 (0.017) | ||

| Age 50–59 | 0.099 (0.017) | 0.142 (0.010) | 0.018 (0.023) | 0.120 (0.027) | ||

| Age 60–69 | 0.159 (0.023) | 0.247 (0.018) | 0.002 (0.031) | 0.147 (0.036) | ||

| Age 70–79 | 0.215 (0.028) | 0.292 (0.026) | −0.028 (0.040) | 0.195 (0.047) | ||

| Age 80 and older | 0.264 (0.034) | 0.366 (0.037) | −0.074 (0.052) | 0.200 (0.058) | ||

| Female sex | 0.023 (0.008) | −0.024 (0.005) | 0.020 (0.011) | 0.044 (0.015) | ||

| Health problem blood pressure | 0.225 (0.012) | 0.089 (0.007) | ||||

| Health problem diabetes | 0.111 (0.030) | 0.132 (0.016) | 0.294 (0.033) | |||

| Health problems eyesight | 0.111 (0.024 | |||||

| Breast cancer screening policy change | 0.079 (0.016) | |||||

| Cervical cancer screening policy change | −0.025 (0.010) | |||||

| Dental policy change | 0.013 (0.010) |

GP, general practitioner; HH, household; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

The effect of having the same screening examination 3 years ago was similar for breast and cervical cancer screening and the marginal effects resulted in an increase in uptake of 12.3% and 12.6%. For individuals who visited their GP in the last year, there was an increase for five of the six analysed health check-ups with only the eyesight test not significant, the increase being highest for blood pressure with a 25.9% increase and lowest for dental screening with a 1.7% increase. Poor self-rated health status increased the uptake of blood pressure checks by about 12.6% and cholesterol tests by about 4.5% and for the eyesight test poor health status increased the uptake by 5.4%. For breast and cervical cancer screening, there was no significant influence of poor health status on uptake. Women aged between 50 and 64 had an increased uptake of 9.9% for breast cancer screening and women aged between 25 and 49 had an increased uptake of 7.3% for cervical cancer screening compared with the reference categories. Also for the other four health check-ups, there was a nonlinear relationship between age and uptake. For blood pressure check, cholesterol test and eyesight test uptake increased non-linearly for the different age categories. Women aged between 65 and 70 had a higher uptake of breast cancer screening after 2002, an increase of 7.9% for this age group in comparison with the years before. Women aged between 25 and 49 had a 2.5% lower uptake of cervical cancer screening after 2003 compared with women of this age group before 2003. Individuals who had a dental screening after 2004 did not have a significant changed uptake in comparison with the years before.

Females had a higher uptake in three of the four analysed health check-ups that are not sex-specific (blood pressure check, dental screening and eyesight tests), but the influence on the uptake of the cholesterol tests was non-significant. The increase in uptake for females was highest for eyesight tests with an increase of 4.4%. The marginal effects for education, employment status, household income, living with a partner, smoking and changed residence status were non-uniform for the different health check-ups. The effect of secondary and tertiary education was strongest for the uptake of dental screening (30.5% and 28.3% increase). Being employed decreased the uptake for breast cancer screening by 3.1%, for blood pressure checks by 2.5% and cholesterol test by 2.2%. Increasing actual household income had no significant effect on any of the uptakes. Living with a partner increased the uptake of dental screening by 3.8%. Smoking decreased the uptake of breast cancer screening by 3.3%, blood pressure checks by 6.3%, cholesterol tests by 2.9% and dental screening by 3.2%. An additional child in the household decreased the uptake of breast cancer screening examinations and blood pressure checks by 2.1% and 2.4%, respectively. Change of residence decreased the uptake of dental screening by 3.5%; however, it increased the uptake of blood pressure checks by 3.6%. Individuals with existing blood pressure problems and diabetes had increased uptake of blood pressure checks by 22.5% and 11.1% and for cholesterol tests by 8.9% and 13.2%, respectively. Individuals with existing eyesight problems and diabetes health problems had an increased uptake for eyesight tests of 11.1% and 29.4%, respectively. Permanent equivalised household income increased the uptake of dental screening and eyesight tests by 2.5% and 1.8%, respectively. Initial conditions show significance for all health check-ups.

Discussion

Our analysis compared the determinants of the uptake of six health check-ups in the UK using the BHPS from 1992 to 2008 (excluding Northern Ireland). We investigated which determinants were the same for all health check-ups and which determinants differed for determining uptake with a focus on the importance of past screening behaviour on actual screening behaviour and health-related variables.

The strong positive significant effect of past screening behaviour shows that past behaviour influences current behaviour and this result can be interpreted as persistence in screening behaviour in the sense of state dependence.56 57 Reasons for the strong positive state dependence are the adherence to the medical screening guidelines in the UK such as the NHSBSP and NHSCSP with explicit recommendations for the time interval between screening examinations. The relevance of these both screening guidelines on current behaviour can be seen in the high predictive value of the coefficients for the same specific screening examination 3 years before. Our results for the high predictive value of a breast or cervical cancer screening examination which had been carried out 3 years ago for the uptake in the current year are in accordance with other results which analysed the uptake for these both screening examinations.27 58 Also the coefficient for the same specific health check-up 1 year before was significantly positive for all the different health check-ups. These results are in agreement with a further analysis which used a lagged dependent variable of uptake one period before as predictor variable and analysed these six different health check-ups.46 Different other studies have confirmed the importance of past screening behaviour for recent uptake of screening examinations such as for mammographies,59 smear tests60 and faecal occult blood test,61 and also a systematic review confirmed that past screening examinations had a positive influence on a recent screening examination.26 Persistence in screening behaviour, control follow-ups to check unclear test results from the previous health check-up and shorter recommended time intervals for some of the analysed health check-up (blood pressure check, cholesterol test, dental screening and eyesight test) are of importance to explain the significance of the 1-year lagged dependent variable as predictor variable. However, with data from the BHPS it is not possible to differentiate between these different possibilities. Initial conditions show relevance in all analysed screening examinations. If initial conditions for the first 3 years would not been taken into account, the influence of past screening behaviour on actual behaviour would have been overestimated, because some of the persistence in screening examinations uptake has been to be attributed to unobserved characteristics. Initial conditions have also to be found significant in other analyses which have used the Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator for the analysis of dynamic panel data models.28

For women the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening is higher in the age group for which it is recommended than in the reference groups and this result has also been found for other empirical studies which has analysed the uptake of screening examinations in the UK27 28 and our results are similar to an Australian study which confirmed that the uptake of the Pap smear test in the recommended age group was also higher than in the non-recommended age group.62 There is a lower uptake of dental screening for older ages in comparison with persons of middle age, and our result is in accordance with another study which has analysed the dental screening uptake with the BHPS in the UK.63 The finding of decreasing screening uptake with increasing age can be explained with the shorter pay-off period for older individuals from the human capital theory approach and are in agreement with a study in the Netherlands for which participation in a health examination increased until age 60 and then decreased.64 For blood pressure checks, cholesterol tests and eyesight tests, uptake increases with age and our results can be explained by the increasing prevalence of hypertension, high cholesterol and eyesight problems at older ages and the necessity to check these specific health problems and are confirmed for these specific health check-ups also by other studies.65

The significance of a GP visit in the year before the actual wave, for all the included health check-ups with the exception of non-significance for the eyesight test, can be explained by the fact that the GP plays an important role as gatekeeper in the UK and also an important role in access to prevention by giving advice about accepting a health check-up or by doing the screening examination42 as it is the case for cervical cancer screening, blood pressure check or cholesterol test. Our results reflect those in an Italian study which analysed the uptake of cervical cancer screening with a recursive probit.31 The regulations for having a smear test are very similar in Italy and the UK with respect to the role of the GP in cervical cancer screening. In both countries a visit to the GP is not an essential condition for the provision of a smear test and this test can also be carried out in specialised services. Estimations from the Italian study showed that GP visits led to an increased uptake of cervical screening. However, the importance of the GP is also significant in our analysis for the health check-ups which are carried out outside of practice: breast cancer screening and dental screening. Two further analyses reinforce the interpretation of the importance of a GP visit as a healthcare provider contact for prevention, because a higher number of healthcare provider contacts increases the uptake rate for breast cancer screening examinations66 and cholesterol tests.65 Furthermore, individuals who visit their GP more often have a higher uptake of general cardiovascular checks in the UK.67 68 The importance of the GP for prevention in the UK is also further strengthened by the fact that individuals who have visited a GP in the previous year have a higher propensity to make an appointment for a health check-up in the recent year.69 In the auxiliary regressions, the averaged value of a GP visit during the past 12 months variable was correlated in five of the six health check-ups with the individual-specific term for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity and could also be caused by unobserved time-invariant factors that have an influence on probability of a GP visit and uptake of the different health check-ups. The effect of self-assessed health status is dependent on the specific health check-up. The uptake of blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests increased with a deteriorating self-assessed health status and was highest for individuals in a very poor health state. Both these health check-ups are often included in a general health check-up for the health status of an individual. The interpretation of health status as a proxy for health stock is most valid for these two health check-ups in comparison with the other health check-ups as individuals in a poor health status have a high demand for these two health check-ups in order to increase their health stock.70 However, poor self-assessed health status can influence uptake also in other ways such as changed perceptions on the preventability of health problems and diseases. Individuals with poorer health status also expressed less interest in receiving prevention information in another study.71 Psychological factors such as fear and anxiety about confirmation of a disease can be related to a poor health status and this correlation could be especially relevant for both analysed female cancer screening examinations. Also individuals with a poor health status could be less able to visit the screening location and these interpretations could explain why such individuals have a lower uptake such as for cervical cancer screening. The effect of self-perceived health status on breast cancer screening was non-uniform in other studies: women with poor or fair self-perceived health status attended mammograms less often than those with good self-perceived health status72; however, another study have found no influence for breast and cervical cancer screening.73

Individuals with blood pressure or diabetes problems had a higher propensity for the blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests and also individuals with eyesight problems had a higher propensity for the eyesight tests, in accordance with the medical guidelines. This is, to our knowledge, the first analysis that compares the uptake rates of blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests for individuals who have blood pressure and diabetes problems with individuals without having these diseases in a longitudinal setting in the UK. Individuals with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases have a higher uptake for a routine check-up by physicians in the USA.70 Smoking had an influence on the uptake of breast cancer screening, blood pressure screening, cholesterol tests and dental screening, but not the other two health check-ups. These results are in accordance with the interpretation that smokers have a risk-taking behaviour and non-smoking women have been found with a higher uptake for breast and cervical cancer screening,72 74 also smoking individuals who registered as patients in a GP practice for the first time have had a lower probability to do a general health check-up.75 However, the effect of smoking with a reduced uptake on health check-ups has not been found in all studies as two systematic reviews have shown.26 40 The change of the medical screening guideline to extend breast cancer screening for women of age 65–70 had the effect of an increased uptake. The reason why the change in the medical screening guidelines for breast cancer screening had the intended effect could be based on the fact that timed appointments are made and there is a strictly policed screening interval. However, the result could be influenced by varying unobservable variables (eg, changing macroeconomic conditions) which are correlated with the policy change dummy variable.

The results for the socioeconomic variables are mixed for the different health check-ups. For women, uptakes in non-specific screening examinations were higher for blood pressure checks, dental screening and eyesight tests, and lower for cholesterol tests and these results were in agreement with three recent studies from the USA.33 70 76 Two systematic reviews find that the uptake of health check-ups is typically higher for women and not for men with the exception of cholesterol tests.26 40 Individuals with a higher education level are more aware of the benefits of preventative care and also early detection of diseases and this explains the higher uptake of preventative activities. Therefore, education has sometimes been found to be an important predictor of uptake of health check-ups,77 78 but a systematic review has found more often not a significant influence on the uptake rates of different health check-ups.26 The hypothesised influence of higher education was, in our analysis, only visible in dental screening and a secondary or tertiary education level had a positive significant influence on the uptake of dental screening. This result is in part explained that education is being correlated with other socioeconomic variables and the inclusion of further socioeconomic variables could explain why the effect on education disappears in the other health check-up regressions. Non-uniform results were also found for other socioeconomic variables for the different analysed health check-ups: employment status as a proxy for opportunity costs of time had a significant negative effect on breast cancer screening, blood pressure checks and cholesterol tests. However, in other studies, the effect of employment status was found insignificant on the uptake of breast cancer screening,79 cervical cancer screening62 and general health check-ups for new GP-registered patients.75 Living with a partner as a proxy for social support and network had only a significant positive effect for dental screening. Most analyses have found no effect of living in a partnership on the uptake for specific health check-ups, for example, breast cancer screening examinations80 and cervical cancer screening examinations.26 A number of children as a proxy for a possible time constraint led to a significant negative effect for breast cancer screening and blood pressure checks. A UK-based study which has analysed the attendance rate for health check-ups in a general practice setting has found that a predictor for attendance was not to have children under 5 and other dependants68; however, the effect of the number of children has not been confirmed in another study for the uptake of breast cancer screening.81 In two systematic reviews, which analysed the determinants of screening uptake for a variety of health check-ups, none of the socioeconomic variables have been significant in all screening examinations.26 40 Actual (transitory) household income had no effect on any of the analysed health check-ups and averaged (permanent) household income had a significant influence only on the uptake for dental screening and eyesight tests. No effect of actual household income on attendance rates has also been found for other screening examinations such as breast cancer screening,82 cervical cancer screening73 and colorectal cancer screening.61 This result is important in comparison with the other analysed free health check-ups, because income effects exist for access to preventative health services for which a charge has to be paid in comparison with preventative services for which no charge exists. Permanent income effects could also be caused by unobserved time-invariant factors that have an influence on income and uptake. Another study which estimated the uptake of the health check-ups with unbalanced panels using the BHPS from 1991 until 2003 confirmed our results only in part, because a transitory income effect was found for the blood pressure check and a permanent income effect was found for dental screening.46

Ethnicity had no significant influence on any of the health check-ups, suggesting that ethnicity is not a cultural barrier for access to preventative services. In comparison with our results, another study using the BHPS that has analysed an unbalanced panel has found a lower uptake for cervical cancer screening for Asian women in comparison with women of other ethnic origin.27 For two studies on the uptake rates of cervical cancer screening in the USA, there has not been found such an influence of ethnicity.83 84 Changed residence and address with a higher chance for not receiving an invitation letter influenced the uptake rate of the various health check-ups unequally: women who had changed residence and address within the UK did not have a lower uptake for breast and cervical cancer screening and so the effectiveness of sending invitation letters for these both female screening examinations is questionable. In agreement with our results for changed residence and address, the length of time an individual woman has lived in her own country and women's postcode of residence have not been a significant predictor of attendance for cervical cancer screening uptake.60 In contrast to these both female cancer screening examinations, it was found that a changed residence with a lower chance of receiving an invitation resulted in a lower uptake for dental screening. Sending invitation letters have also been reported to be successful in increasing the participation rates of dental screening.85 The implementation for the different health check-ups with sending routine periodic invitation letters to individual women for breast and cervical cancer screening, with the decision about invitation left for individual practices for eyesight test and dental screening and as an invitational programme for blood pressure check and cholesterol test could have influenced the uptake rates for the different health check-ups in different ways; however, there is no information in the BHPS available how the invitational programmes are implemented on an individual practice level. The effectiveness of sending invitation letters for increasing participation rates for blood pressure checks has been shown86; however, invitational follow-up letters have not contributed to increase participation in comparison with a control group for the cholesterol test.87

There are some differences when comparing our results on the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening with other studies which had analysed the uptake behaviour for the UK and used the BHPS as sample. Analysis of breast cancer screening uptake with the BHPS was carried out in one analysis with a balanced sample.28 Identical results were found for the relevance of previous screening history, a GP visit, age and self-assessed health status; however, the results were different to our results for smoking status, education level, marital status and the average household income, because they were significant in this analysis. The different results for the later mentioned variables are best explained by choosing different specifications in the two empirical analyses. Analysis of cervical cancer screening uptake with the BHPS was carried out in a further analysis with a balanced sample. In our analysis, previous screening history, age and a GP visit were significant for cervical cancer screening in the UK and our results were confirmed by this study which analysed uptake of cervical cancer screening in England with an unbalanced panel for the first 12 waves of the BHPS until 2003.27 The coefficients for education, smoking and changed residence status were not significant in our analysis. The differences in results for the variables education and smoking are remarkable, because in our analysis they had not been significant. However, also some other studies have found no influence of education60 and smoking status88 on cervical cancer screening uptake. Only one analysis has compared the sociodemographic determinants for the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening at the same time for the UK with a cross-sectional survey.2 Results for the effects of determinants on the uptake of both female cancer screening examinations were different, because for mammography level of education, occupational classification and ethnicity were not significant and only indicators for wealth were positively significant. For having a smear test, a higher educational level and white British ethnicity were positively significant, but not indicators for wealth or occupational classification. This is one of the few studies which has compared the determinants of the uptake of breast and cervical screening and has found different determinants to be responsible for the uptake of both screening examinations. An advantage of this analysis was that is used the same estimation sample for the analysis, however unobserved heterogeneity and state dependency could not be taken into account with cross-sectional data in this analysis and this could explain the different results to the results of our own study. One study with the BHPS found in a descriptive analysis that females reported a higher uptake than males for dental check-ups under NHS provision.63 Individuals between age 46 and 55 years had the highest proportion of dental check-ups with 72% in 2000 and the lowest participation rate was for individuals of age 66 years and older with 43% in 2000. These results are confirmed in our analysis. Another study which used the BHPS to investigate the probability of making a dental check-up visit in 1, 3, 5 and 10 years in comparison with the baseline period of 1991 found that in each of these time periods from 1991 to 2001, females, more educated and non-smokers had a higher uptake which is in accordance with our results. However, in contrast with our results, persons below age 40 had the highest rate of uptake and this result could be explained by the fact that only a distinction between individuals below age 40 and above age 40 was made.

The first limitation of our study is that there is no information about results from previous screening examinations available and it is not possible to differentiate between types of health check-ups: preventative health check-ups according to screening guidelines, health check-ups following the advice of a GP or consultant to do a test or health check-ups which are in response to previous inconclusive results. There is also no information available about close female relatives with a history of breast or cervical cancer. The second limitation of our study is that no information was available about the level of trust in the NHS or in the GP, because it has been shown that taking part in screening examinations can be dependent on trust.31 The third limitation exists, because there was no information available about the characteristics of the primary care factors that have been shown to be associated with the uptake of screening examinations in England.89 Characteristics of the professional performing of the screening test, structure and organisation of medical services can influence the uptake rate. The fourth limitation of our study comes from not using detailed microgeographic information, because uptake rates for a specific health check-up can be higher in affluent and less-deprived areas.90

Conclusions

Our analysis compares for the first time the determinants of six different NHS health check-ups and has a focus on health-related variables such as the role of the GP, health status and existing health problems for these six different health check-ups. A further innovative feature of our study is the analysis of the uptake of different health check-ups with a REs panel probit model with initial conditions (Mundlak-Wooldridge estimator) and a balanced sample, because some other analyses have used cross-sectional data and unbalanced panels with the possible problem of an attrition bias. Our research shows the high importance of past screening behaviour for each of the analysed health check-ups for recent screening behaviour and it is important, therefore, to maintain a high level of prevention uptake. The GP plays a central role in the uptake of screening examinations and this role in prevention in the UK healthcare system should not be weakened. Existing diseases are, as expected, important predictors for the specific health check-up. Income barriers could be removed for health check-ups such as dental screening and eyesight tests to increase the uptake for individuals with limited financial possibilities. Future research could use information about results from previous screening examinations and microgeographic information by linking with other data sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the SPECTRE High Performance Computing Facility at the University of Leicester.

Footnotes

Contributors: AL performed statistical analyses. AL, RB and FP discussed the results, and contributed to the text of the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The research was funded by and took place at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care based at Leicester.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- 1.Damiani G, Federico B, Basso D, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening in Italy: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moser K, Patnick J, Beral V. Inequalities in reported use of breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: analysis of cross sectional survey data. BMJ 2009;338:b2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advisory Committee on Breast Cancer Screening. Screening for breast cancer in England: past and future NHSBSP. http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/nhsbsp61.pdf Publication No 61 (accessed 3 Nov 2013)

- 4.NHS Cervical Screening Programme. http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/publications/reviews-leaflets.html (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 5.Macmillan Cancer Support Cervical Screening. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Cancerinformation/Testsscreening/Cervicalscreening/Cervicalcancerscreening.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 6.Public Health England UKNSC policy database. The UK NSC policy on cervical cancer screening in women. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/cervicalcancer (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 7.ISD Scotland Cervical cancer screening. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Cancer/Cervical-Screening/ (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 8.NHS Wales Cervical screening Wales. http://www.screeningservices.org.uk/csw/pub/ (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 9.Government Statistical Service Cervical statistics bulletin: cervical screening programme, England: 2002–2003. http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/cervical-statistics-bulletin-2002–03.pdf (accessed 3 Nov 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasieni P, Adams J, Cuzick J. Benefit of cervical screening at different ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories. Br J Cancer 2003;89:88–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blood Pressure UK Blood pressure checks and readings. http://www.bloodpressureuk.org/microsites/u40/Home/checks (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 12.NHS NHS choices. High blood pressure (hypertension)—diagnosis. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Blood-pressure-%28high%29/Pages/Diagnosis.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 13.NHS NHS choices. High cholesterol—diagnosis. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cholesterol/Pages/Diagnosis.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 14.Life Line Screening High cholesterol screening by life line screening. http://www.lifelinescreening.co.uk/health-screening-services/heart-disease/high-cholesterol.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 15.NHS NHS choices. Dental check-ups. http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/dentalhealth/Pages/Dentalcheckups.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 16.NHS Scotland Counter Fraud Services Dental. https://cfs.scot.nhs.uk/dental.php (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 17.NHS Direct Wales Local services dentists—frequently asked questions. http://www.nhsdirect.wales.nhs.uk/localservices/dentistfaq/ (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 18.NHS NHS choices. Eyecare entitlements. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/Healthcosts/Pages/Eyecarecosts.aspx (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 19.NHS Scotland Counter Fraud Services Sight. https://cfs.scot.nhs.uk/sight.php (accessed 3 Nov 2013).

- 20.Grossman M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ 1972;80:223–55 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenkel DS. Prevention. In: Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP, eds. Handbook of health economics. Vol 1,Chap 31 North Holland: Elsevier, 2000:1675–720 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehrlich I, Becker GS. Market insurance, self-insurance, and self-protection. J Polit Econ 1972;80:623–48 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selden TM. Uncertainty and health care spending by the poor: the health capital model revisited. J Health Econ 1993;12:109–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zweifel P, Breyer F, Kifmann M. Health economics. Berlin: Springer, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cropper ML. Health, investment in health, and occupational choice. J Polit Econ 1977;85:1273–94 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jepson R, Clegg A, Forbes C, et al. The determinants of screening uptake and interventions for increasing uptake: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:1–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabates R, Feinstein L. The role of education in the uptake of preventative health care: the case of cervical screening in Britain. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:2998–3010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carney P, O'Neill S, O'Neill C. Determinants of breast cancer screening uptake in women, evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. Soc Sci Med 2013;82:108–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenkel DS. The demand for preventative medical care. Appl Econ 1994;26:313–25 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lairson DR, Chan W, Newmark GR. Determinants of the demand for breast cancer screening among women veterans in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1608–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrieri V, Bilger M. Preventive care: underused even when free. Is there something else at work? Appl Econ 2013;45:239–53 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, et al. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract 2000;49:147–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]