Abstract

Objectives

To define an easy-to-use model for prediction of survival time in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer in order to optimise patient' care.

Design

An observational retrospective study on patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. The initial radiographs at presentation of symptoms were reviewed and the maximum diameter of the primary tumour was determined. The occurrence of liver metastases and performance status that determines initiation of chemotherapy was also used in the regression analysis to identify prognostic subgroups.

Setting

County hospital in south-east of Sweden.

Population

Consecutive patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer who were diagnosed between January 2003 and May 2010 (n=132).

Main outcome measures

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.13. Survival time was assessed with Kaplan-Meier analysis, log-rank test for equality of survivor functions and Cox regression for calculation of individual hazard based on tumour diameter, presence of liver metastases and initiation of chemotherapy treatment according to patient performance status.

Results

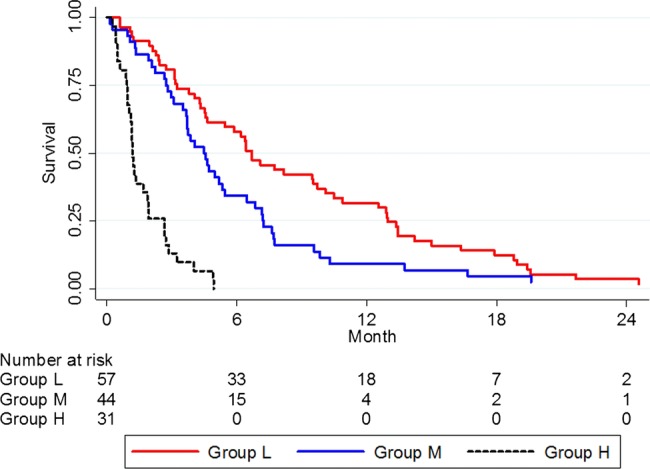

The individual hazard was log h=0.357 tumour size+1.181 liver metastases−0.989 performance status/chemotherapy. Three prognostic groups could be defined: a low-risk group with a median survival time of 6.7 (IQR 9.7) months, a medium-risk group with a median survival time of 4.5 (IQR 4.5) months and a high-risk group with a median survival time of 1.2 (IQR 1.7) months.

Conclusions

The maximum diameter of the primary tumour and the presence of liver metastases found at the X-ray examination of patients with pancreatic cancer, in conjunction with whether or not chemotherapy is initiated according to performance status, predict the survival time for patients who do not undergo surgical resection. The findings result in an easy-to-use model for predicting the survival time.

Keywords: Surgery, Oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The data cover every patient with unresectable pancreatic cancer at a single hospital between January 2003 and May 2010.

With the described model, it is possible to identify patients with a very short expected survival time and those patients who are likely to have a somewhat longer duration of survival.

The knowledge of expected survival may improve opportunities to individualise optimal patient care.

One limitation is that the validation of the proposed model for prediction has to be conducted.

Background

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a highly fatal neoplasm and one of the leading causes of death in cancer in the Western world. The prognosis of patients with unresectable pancreatic carcinoma is extremely poor with no prospects of a 5-year survival rate.1 The disease is difficult to treat because clinical presentation is often late, and most of the patients have an advanced tumour burden with a high incidence of metastatic disease at diagnosis. In a recent Swedish study, tumour size—but not length of bile duct stricture—measured at the initial radiographic examination predicted the survival rate of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer.2 Identifying factors that can accurately predict the duration of disease survival is potentially helpful in the treatment of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. It may be unsuitable for patients with a bulky tumour to be exposed to cytotoxic chemotherapy or other advanced palliative therapies, as it may not prolong their survival but instead impair the quality of their short remaining lives. Could information that is readily available to clinicians at the time of diagnosis be used to predict survival time?

The purpose of this study is to examine whether tumour size and the presence of liver metastases at initial radiographic imaging, studied in conjunction with the decision to start chemotherapy based on patient performance status, can predict survival length in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer and identify prognostic subgroups among patients by calculating individual hazards after Cox regression.

Method

During the period January 2003–May 2010, 185 consecutive patients were diagnosed with ductal pancreatic cancer and recruited into a single centre study. Only patients with a diagnosis of cancer in the caput, corpus and cauda of the pancreas, or carcinoma growth outside the pancreas into adjacent organs were enrolled. Patients who had undergone surgery for curative purposes, that is, Whipple procedure or total pancreatectomy, were excluded from this survey. The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was based on radiographic examinations but cytological specimens were also performed. Initial radiographs following admittance to the hospital were retrieved and re-examined, all by the same radiologist, and tumour size was measured again. For a more detailed description of this procedure of tumour evaluation see Forssell et al.2 In summary, most patients were examined with multislice CT with a slice thickness of 2 mm. The maximum tumour diameter could be measured in 132 patients, in 114 with CT and the rest, 18 (14%) patients, with transabdominal ultrasound examination. In 53/185 (29%) cases, the image of the tumour was far too diffuse to be measured by standard radiological means and these patients were not accounted for in this study. First, when the tumour was measurable, the median tumour maximum diameter was 4.35 cm and therefore the study material was classified into two equal groups with the cut-off diameter at 4.3 cm. Second, occurrence of liver metastases at the time of diagnosis was noted and the patients were divided into two groups depending on whether or not liver metastases were present. Third, patients were divided into two groups of performance status, good or bad, corresponding to a Karnofsky scoring index above or below 50%. The decision to offer chemotherapy was entirely based on whether the patient performance status was good, that is, clinical judgement, taking into account the patient's general level of fitness, comorbidity and overall likelihood of benefitting from such treatment. If patients were offered chemotherapy it always started with gemcitabine. A second-line chemotherapy consisted of 5-fluorouracil/calcium folinate (5 patients), capecitabine (6 patients) or oxaliplatin (1 patient). Patient characteristics are given in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with primary unresectable pancreatic neoplasm

| Patients | 132 |

| Female/male | 75/57 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 74 (64–81) |

| Age ≤65/>65 years (%) | 40/92 (30/70) |

| Tumour diameter ≤4.3 cm (%) | 66 (50) |

| Tumour diameter >4.3 cm (%) | 66 (50) |

| Liver metastases (%) | 60 (45) |

| Performance status, corresponding to Karnofsky index >50% | 57 (43) |

| Chemotherapy started with gemcitabine (%) | 57 (43) |

| Second-line chemotherapy after gemcitabine treatment (%) | 12 (9) |

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Stata V.13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as median values (IQR) and were compared with two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The comparison among groups for categorical variables was performed with Pearson χ2 test. Overall survival estimates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference between groups was assessed by the log rank. Survival rates are given as median and IQR. Survival curves were truncated at 24 months, since the number of patients at risk after that time was very small. Independent factors for overall survival were assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. The relative hazard for each patient was calculated from coefficients received by Cox regression.3 A p value <0.050 was considered statistically significant.

Results

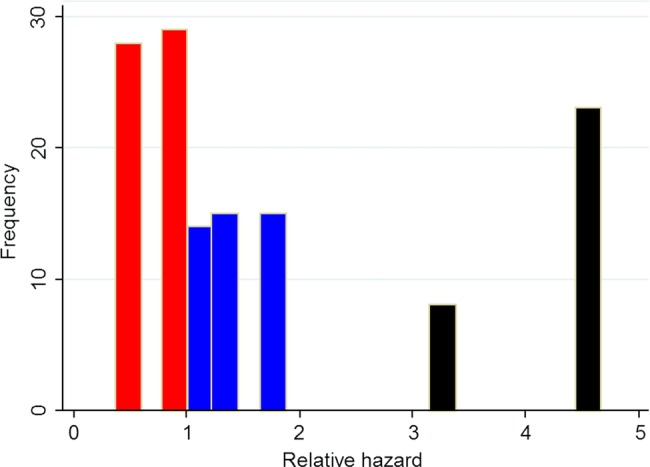

A total of 132 of 185 patients had a measurable tumour and were included in the study with a median age of 74 (IQR 64–81) years. Of these, 75 were women and 57 were men. Liver metastases were found in 60 patients (45%) at the initial radiological investigation and presentation of symptoms. Median survival times for patients with different tumour sizes according to liver metastases and given chemotherapy treatment are shown in table 2. In the group with failed cytological proven ductal adenocarcinoma (about half of the enrolled patients), the overall survival time was the same as in those patients with proven cancer. There were no differences in overall survival rate between patients included in 2003–2006 and 2007–2010 (p=0.629). In the 53 patients with no measurable tumour, the median overall survival time was 3.3 months and not significantly different from 4.9 months in those patients with a tumour size ≤4.3 cm or 3.1 months if tumour was >4.3 cm. A Cox regression was performed to identify prognostic subgroups of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer (table 3). The final form of the Cox model calculated from data from the 132 patients with ductal pancreatic neoplasm is shown in the lower part of table 3. This corresponds to log h=0.357, tumour size +1.181, liver metastases −0.989 performance status/chemotherapy. Tumour size ≤4.3 cm, no liver metastases and performance status bad/no given chemotherapy were all coded as 0 and the other alternatives as 1. By using the formula, each individual relative hazard (h) was calculated. Three prognostic groups were defined according to the frequency distribution of the relative hazard: a low-risk group, h≤1; a medium-risk group, h>1 but ≤2; and a high-risk group, h>2. Distribution of relative hazard in 132 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer is shown in figure 1. The corresponding survival rates are shown in table 4. Log-rank tests for equality of survivor functions between the three groups indicated significant differences in the survival rate, p<0.001, figure 2.

Table 2.

Median survival time for patients according to tumour size, presence of liver metastases and started chemotherapy in days

| No liver metastases | Liver metastases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | No chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | All | No chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | |

| Tumour ≤4.3 cm | 204 | 131 | 392 | 111 | 59 | 117 |

| Tumour >4.3 cm | 157 | 107 | 196 | 58 | 35 | 139 |

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable regression | |||

| Tumour size, ≤4.3 cm, >4.3 cm | 1.51 | 1.07 to 2.13 | 0.020 |

| Liver metastases, no, yes | 2.35 | 1.63 to 3.38 | <0.001 |

| Performance status, bad (no chemotherapy), good (chemotherapy started) | 0.56 | 040 to 0.81 | 0.002 |

| Age, ≤65 years, >65 years | 0.93 | 0.67 to 1.30 | 0.690 |

| Age groups | |||

| 40 | 1 | ||

| 50 | 2.29 | 0.53 to 9.91 | 0.269 |

| 60 | 1.66 | 0.40 to 6.87 | 0.481 |

| 70 | 1.41 | 0.34 to 5.79 | 0.638 |

| 80 | 1.55 | 0.38 to 6.38 | 0.541 |

| 90 | 3.69 | 0.77 to 17.5 | 0.102 |

| Sex, male, female | 0.93 | 0.70 to 1.25 | 0.689 |

| CRP | 1.001 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.176 |

| Multivariable regression | |||

| Tumour size, ≤4.3 cm, >4.3 cm | 1.43 | 1.01 to 2.04 | 0.048 |

| Liver metastases, no, yes | 3.26 | 2.16 to 4.92 | <0.001 |

| Performance status, bad (no chemotherapy), good (chemotherapy started) | 0.37 | 0.25 to 0.55 | <0.001 |

CRP, C reactive protein.

Figure 1.

Distribution of relative hazard in 132 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, red bar=low, blue bar=medium and black bar=high-risk group, corresponding to the three subgroups shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival for prognostic subgroups

| Risk group | Relative hazard | Number of patients (%) | Median (IQR) survival, months | 3-month survival rate (%) | 6-month survival rate (%) | 12-month survival rate (%) | 18-month survival rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | ≤1 | 57 (43) | 6.7 (3.2–13.0) | 81 | 58 | 32 | 12 |

| Medium | >1 to ≤2 | 44 (33) | 4.5 (2.7–7.2) | 70 | 34 | 9 | 5 |

| High | >2 | 31 (24) | 1.2 (0.9–2.7) | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Figure 2.

Survival analysis in patients divided into low-risk (L), medium-risk (M) and high-risk (H) prognostic subgroups, N=132; p<0.001.

Discussion

Our findings highlight three important factors that contribute to overall survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, that is, tumour size defined as the tumour's maximum diameter, the presence of liver metastases and patient performance status allowing starting chemotherapy. Those patients with good performance status corresponding to a Karnofsky index above 50% received chemotherapy. We have previously found that survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method showed a better survival rate in unresectable pancreatic cancer if the tumour size was below 4.3 cm.2 By using Cox regression, adjusted for occurrence of liver metastases and performance status to decide if chemotherapy should start or not, the individual relative hazard was calculated. Age, gender and C reactive protein (CRP) were not included in this calculation since these variables had no influence on the final multivariable Cox regression. Three different prognostic groups could be determined from the frequency distribution of individual hazard and the survival rate was clearly different between these groups (p<0.001), ranging from median 1.2 to 6.7 months (figure 2). An easy-to-use model for prediction of survival in unresectable pancreatic neoplasm is therefore proposed, which discriminates survival better than predictions based on only tumour size, the presence of liver metastases or performance status to decide treatment with chemotherapy. The characteristics of the three groups are given in table 5. The model is really a condensation of 8 (23) groups, that is two groups based on tumour size×two groups based on liver metastases×two groups based on performance status and initiation of chemotherapy treatment. The model also reveals a shift to a better risk group for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer who start chemotherapy treatment. In the high-risk group, tumour size has no influence on survival, which in their case is extremely short, about 1 month. The proposed model combines measurable hard data from initial radiographic examinations, in the form of tumour size and presence of liver metastases, with a somewhat weaker variable in the form of patient performance status and the physician-based decision to initiate chemotherapy or not. A clinical decision like this may be prone to individual bias in how the patient's general level of fitness, comorbidity and overall likelihood of benefitting from treatment is assessed. This may be seen as a potential limitation to the model's usefulness and reproducibility. However, it was necessary to give some form of consideration for performance status/chemotherapy in the model, as the initiation of cytotoxic drug clearly has a considerable impact on patient survival as shown in table 2. Even if it is not an exact factor, excluding the performance status/chemotherapy variable would reduce the regression model too much. We, therefore, chose to deal with it in our calculations and to adjust for it in the regression analysis.

Table 5.

Risk groups according to liver metastases, performance status/initiation of chemotherapy and tumour size

| Liver metastases | Performance status | Tumour size, cm | Risk group | Median survival (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Good, chemotherapy | Any | Low | 6.7 (3.2–13.0) |

| Bad, no chemotherapy | ≤4.3 | |||

| No | Bad, no chemotherapy | >4.3 | Medium | 4.5 (2.7–7.2) |

| Yes | Good, chemotherapy | Any | ||

| Yes | Bad, no chemotherapy | Any | High | 1.2 (0.9–2.7) |

Another limitation of our study is that only half of the patients had cytological verified ductal adenocarcinoma and this highlights the clinical problems in managing pancreatic neoplasm and that in many cases the diagnose needs to rely on radiological examinations. However, in our study, there was no difference in survival whether cytological diagnosis could be obtained or not. Nor were there any difference in overall survival with respect to enrolment periods and possible changes in second-line chemotherapy.

The strengths of this study are that it includes consecutive patients from a single medical centre and that all initial X-rays following admittance to the hospital were re-examined, all by the same radiologist. The prediction may be carried out immediately after radiological investigations and assessment of patient performance status, thereby not losing time while waiting for additional examinations. For a comprehensive summary of the previous literature on prognostic factors in pancreatic cancer, see Stocken et al.4 Factors implicated by more than one previous researcher can be broadly attributed to one of the five following groups: (1) factors describing tumour burden, that is, tumour size, tumour, node and metastasis disease stage and presence of metastases, not necessarily confined to the liver5; (2) factors describing the patient's fitness level, that is, performance status or nutritional status6; (3) biochemical variables from blood, with varying degrees of disease specificity, with the non-specific inflammatory marker CRP most frequently mentioned, but including many others, like the tumour markers CA 19–9 and CA 2424 7; (4) immunohistochemical analyses from pathological specimens, where more than 11 are identified as relevant in two or more studies, but none validated highly enough to be recommended for use in clinical practice as of now8; and (5) treatment factors, that is, surgery and/or chemotherapy.1 9 10 We find that our model fits these previous findings quite well. In our study, CRP had no impact on the final model for prediction of overall survival. However, it may require expansion to accommodate information from those groups that are not represented at present, that is, blood laboratory and immunohistochemistry. The variable performance status/initiation of chemotherapy in its current form is likely to reflect the biological effect that the drug has on tumour cells and a selection bias in who receives treatment. It may in the future be modified to better reflect the difference between these two effects. The clinical implications of being able to give patients a more individualised prognosis are quite clear in order to improve optimal patient care. Patients with an extremely short survival should have best supported care and those with a better predicted survival may be selected for radiochemotherapy. Also, as previously suggested by another research team, a more accurate individual prognosis may influence the choice between plastic and metal biliary stents for palliation of obstructive jaundice.5 The initiation of chemotherapy treatment is correlated to survival advantages across all levels of tumour burden. It is not possible to determine which patients should have chemotherapy treatment based solely on the evaluation of initial patient X-rays. The survival advantages of chemotherapy are at least obvious in the low-risk group, where we can observe a non-significant tendency towards longer survival among those treated. In the future, we have plans to validate the findings of our model, using a new cohort of patients at our centre who were diagnosed with unresectable pancreatic cancer from 2010 onwards. The model may also be expanded with new variables according to our previous line of discussion. Closer determination of what factors warrant the initiation of chemotherapy merits attention. Ideally, an effort should be made to adjust the survival times for quality of life during the disease.

Conclusion

We propose an easy-to-use decision model which can predict survival time in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer by determining the maximum diameter of the primary tumour and the presence of liver metastases at the patient's initial radiological examination, together with performance status information to initiate chemotherapy. With the described model, it is possible to identify patients with a very short expected survival time, and those patients who are likely to have a somewhat longer duration of survival. This knowledge may improve opportunities to individualise optimal patient care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors substantially contributed to the current manuscript as listed below: HF drafted the manuscript, is the principal investigator of the study and designed this study. KÅ reviewed and measured tumour size of all X-rays. MW, KÅ, SJ revised the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from Blekinge County Council's Research and Development Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (EPN Dnr 2012/92).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wilkowski R, Wolf M, Heinemann V. Primary advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 2008;177:79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forssell H, Pröh K, Wester M, et al. Tumor size as measured at initial X-ray examination, not length of bile duct stricture, predicts survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2012;12:429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machin D, Cheung YB, Parmar MKB. Survival analysis. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2006:187–206 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocken DD, Massan AB, Altman DG, et al. Modelling prognostic factors in advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2008;99:883–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber A, Kehl V, Mittermeyer T, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 2010;39:247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terwee CB, Nieveen Van Diikum EJ, Gouma DJ, et al. Pooling of prognostic studies in cancer of the pancreatic head and periampullary region: the Triple-P study. Triple-P study group. Eur J Surg 2000;166:706–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tingstedt B, Johansson P, Andersson B, et al. Predictive factors in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: role of the inflammatory response. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:754–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansari D, Rosendahl A, Elebro J, et al. Systematic review of immunohistochemical biomarkers to identify prognostic subgroups of patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2011;98:1041–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riall TS, Nealon WH, Goodwin JS, et al. Pancreatic cancer in the general population: improvements in survival over the last decade. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1212–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sultana A, Cox T, Ghaneh P, et al. Adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 2012;196:65–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.