Abstract

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the commonest valve disorder in the developed world requiring surgery. Surgery in patients with severe asymptomatic AS remains controversial. Exercise testing can identify asymptomatic patients at increased risk of death and symptom development, but with limited specificity, especially in older adults. Cardiac MRI (CMR), including myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR) may be a novel imaging biomarker in AS.

Aims

(1) To improve risk stratification in asymptomatic patients with AS and (2) to determine whether MPR is a better predictor of outcome than exercise testing and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP).

Method/design

Multicentre, prospective observational study in the UK, comparing MPR with exercise testing and BNP (with blinded CMR analysis) for predicting outcome.

Population

170 asymptomatic patients with moderate-to-severe AS, who would be considered for aortic valve replacement (AVR).

Primary outcome

Composite of: typical symptoms necessitating referral for AVR and major adverse cardiovascular events. Follow-up: 12–30 months (minimum 12 months).

Primary hypothesis

MPR will be a better predictor of outcome than exercise testing and BNP.

Ethics/dissemination

The study has full ethical approval and is actively recruiting patients. Data collection will be completed in November 2014 and the study results will be submitted for publication within 6 months of completion.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study design: blinded imaging with core lab analysis (cardiac MR (CMR) and exercise testing) to reduce referral bias, inclusion only of patients who would consider surgery, multicentre, data collection/analysis by independent clinical trials unit.

Comprehensive phenotyping of participants.

Management and oversight: independent chair and members of steering committee, independent event adjudication.

Harder primary endpoint: asymptomatic patients referred for aortic valve replacement not included.

Registration with National Health Service Information services to minimise loss to follow-up and acquire long-term data.

Coronary disease not excluded by angiography.

CMR not widely available in all secondary care settings.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the commonest valve lesion requiring surgery in the developed world.1 European registry data indicate that as few as 30% of potentially eligible patients are referred for surgery.2 As the population in developed countries continues to age, it is predicted that the prevalence of AS will double in the next 20 years.3

The development of symptoms in AS heralds a malignant phase of the condition and prompt aortic valve replacement (AVR) results in a clear reduction in mortality.4 Surgery in this situation is universally regarded as a class I indication despite the absence of randomised controlled trials.5 6 In contrast, management of patients with severe AS in the absence of symptoms remains controversial and continues to provoke debate, with divergent clinical practice.7 8 It is generally agreed that the ideal timing of surgical intervention is immediately before a patient develops symptoms. Such a strategy, if successfully implemented, would minimise the risk of sudden death during the long latent (asymptomatic) period and minimise the number of patients sent for surgery who may never have developed symptoms related to AS.

Risk stratification in asymptomatic patients with moderate-to-severe AS

Many researchers have therefore sought clinical markers in asymptomatic patients with AS, that reliably identify those who will need AVR. The current body of evidence in asymptomatic AS consists mainly of observational studies (table 1), which have identified a number of risk factors for developing symptoms or death.8 9 These include (1) echocardiographic markers: aortic valve calcification, rapid increase in pressure gradient,10 very high aortic valve velocities11 12; (2) an abnormal response or symptoms on exercise testing13–15 and (3) abnormal biomarkers, especially brain natriuretic peptides (BNP).16 It should be noted, however, that echocardiographic measures of AS severity are a poor discriminator between those who go on to develop symptoms and those that do not, compared with other parameters.13 17

Table 1.

Prospective studies assessing risk stratification in moderate-to-severe asymptomatic AS

| Author | N | Severity | CAD | Outcome | Follow-up: months | AVR | Total/cardiac deaths | SCD | Outcome predictor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosenhek et al10 | 128 | Severe (>4 m/s) | Not exclude | Death, AVR | 22±18 | 59 of 106 (56%) | 8 6 cardiac |

1 (0.9%) | Calcification, rapid progression |

| Amato et al13 | 66 | Severe (AVA <1 cm2) | Excluded (angio) | Death, symptoms | 15±12 | ?34 | 4 | 4 (6.1%) | AVA <0.7 cm2, positive ETT |

| Lancellotti et al14 | 69 | Severe (AVA <1 cm2) | Not excluded | Symptoms, death, AVR | 15±7 | 12 (17%) | 3 cardiac + 1 death post-AVR | 2 (2.9%) SCD | Exercise mean PG +ve ETT, AVA <0.75 cm2 |

| Das et al15 | 125 | Moderate-to–severe (AVA <1.4 cm2), | Not excluded | Symptoms, death | 12 | 36 (29%) symptoms? AVR | No deaths | No SCD | Exercise symptoms |

| Monin et al40 | 104 | Moderate-to-severe: >3 m/s AVA <1.5 cm | RWMA exclude | Indication for AVR, death | 24 | 58 AVR | 4 deaths (1 post-AVR) | Female sex, BNP, peak velocity | |

| Rosenhek et al12 | 116 | Very severe >5 m/s | Not excluded | Indication for AVR, death | 41 (median) | 79 AVR, 10 refused AVR | 17 deaths 9 no surgery 8 post-AVR |

1 SCD | Peak AV >5.5 m/s, diabetes, cholesterol |

| Kang et al11 | 197 | Very severe >4.5 m/s or AVA <0.75 cm2 | History or RWMA | Death | 42 AVR 58 medical |

148 102 early, 46 (of 95) medical |

3 (0 cardiac) early, 28 (12 cardiac) medical | 9 (10%) medical 0 early |

Peak AV >5 m/s |

| Cioffi et al20 | 209 | Severe (AVA<1 cm2 or mean PG>40 mm Hg | History | Death, AVR, MI, HF hospitalisation | 22±13 | 72 | 20 (16 cardiac) | 2 SCD | Inappropriate high LVMI, peak velocity, calcification |

Source: Adapted from ref. 9-reproduced with permission.

Angio, coronary angiography; AS, aortic stenosis; AV, aortic valve velocity; AVA, aortic valve area; AVR, aortic valve replacement; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CAD, coronary artery disease; ETT, exercise tolerance test; HF, heart failure; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; PG, pressure gradient; RWMA, regional wall motion abnormalities; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Limitations of current research in asymptomatic AS

The limitations of these research studies have been highlighted in a recent editorial.9 These include a degree of selection bias due to non-randomisation, unblinded investigations influencing management decisions and patients who subsequently refuse surgery and patients undergoing AVR while asymptomatic being included in the primary outcome.

Exercise testing to risk stratify in AS

Of the prognostic markers studied to date, most attention has focused on exercise testing.13–15 A recent meta-analysis of stress testing in 491 asymptomatic patients with severe AS demonstrated that there was no sudden death in those with a normal test, which was also associated with a low risk of subsequent events.18 However, the specificity of a positive test is low for predicting outcome. Das et al15 showed the positive predictive value of exercise symptoms to be only 57% and even lower in the large and important group of patients >70 years of age. It does seem likely that the mechanisms limiting exercise capacity will closely be related to those that cause symptoms. However, no trial to date has assessed whether early AVR can improve outcome in asymptomatic patients with a positive exercise test (or for any other risk factor). For this reason the ACC/AHA guidelines grade exercise-induced symptoms as a class IIB indication (can be considered but weight of evidence does not support intervention) for AVR.19 Exercise testing has not been widely implemented in clinical practice.2

Importance of left ventricular remodelling in AS

The hypertrophic response to pressure overload in severe AS is extremely variable.20 21 When left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) does occur, it is associated with a number of detrimental pathophysiological sequelae: reduction in myocardial strain,22 development of myocardial fibrosis23 and diastolic dysfunction. These changes are also associated with microvascular dysfunction.24 Patients with AS with high left ventricular mass index (LVMI) are more likely to develop heart failure, suggesting that adverse ventricular remodelling is promotive of LV systolic dysfunction.21 Inappropriately high LVMI has also been identified as an adverse prognostic marker in patients with severe asymptomatic AS.20

Following AVR there is regression of LVH which has been associated with improvement in myocardial strain,22 myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR)25 and exercise capacity,26 but not in all studies.27 However, there are concerns that LVH regression is incomplete and that myocardial fibrosis may be irreversible leading to persistent diastolic dysfunction and increased long-term mortality.28

Cardiac MR in AS

Focal myocardial fibrosis can be detected non-invasively by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in 27–62% of patients with AS.29 30 The extent of LGE correlates well with, although underestimates the extent of interstitial fibrosis on myocardial biopsy29 31 and increases with LVH.29 30 LGE in patients with severe AS is associated with limited improvement in symptoms, LV function and higher medium-term mortality after AVR.29 31

Cardiac MR (CMR) myocardial tissue tagging can also demonstrate alterations in strain and strain rates, and is considered the gold standard technique for the assessment of function.32 In AS there is an increase in the normal wringing action (torsion) of the LV, which improves after AVR.33 The rate of untwisting in AS is reduced which may reduce diastolic filling and MPR by loss of ‘suction’ action.

The importance of CMR detected LVH, LGE and MPR in predicting objectively measured maximal aerobic exercise capacity (peak oxygen consumption (VO2)) in 46 patients with severe isolated AS prior to AVR has been studied.34 On stepwise regression analysis, MPR was the only independent predictor of sex and age-corrected peak VO2, β=0.457, p=0.001. MPR also significantly decreased with increasing New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class (p=0.001). Newer CMR methods utilising T1 mapping also offer the possibility of quantifying diffuse myocardial fibrosis not detected by the LGE technique.26 This has also been shown to be associated with exercise capacity and NYHA class in patients with severe AS prior to AVR.26 Diffuse fibrosis may be an important determinant of MPR preoperatively. However, early after AVR there is no significant change in diffuse fibrosis26 28 but MPR does increase25 (reflecting changes in pressure overload and reverse LV remodelling34).

MPR is an attractive biomarker in AS since it is dependent on a combination of factors that include: valve severity and measures of LV remodelling/fibrosis and perfusion time. The primary aim of the PRIMID AS study is to assess whether MPR (and other CMR measures) can improve risk stratification in asymptomatic patients with moderate-to-severe AS, by comparing them to the best studied prognostic indicators: exercise testing and NT-proBNP.

Study design

This is a multicentre, prospective observational study with blinded analysis of CMR data. The study has been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01658345).

Aims of the study

To improve risk stratification in asymptomatic patients with AS.

To determine whether MPR is a better predictor of outcome than exercise testing and NT-proBNP.

To establish the determinants of MPR in asymptomatic AS.

Two substudies will:

Assess the reproducibility of MPR measurement in AS;

Assess the rate of progression in LV remodelling at 1 year in asymptomatic AS.

Primary hypothesis

MPR will be a better predictor of adverse outcome than exercise testing in asymptomatic patients with moderate-to-severe AS.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

These are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Moderate-to-severe AS (≥2 of: AVA <1.5 cm2, peak pressure gradient >36 mm Hg, mean PG >25 mm Hg) | History of CABG or recent MI within 6 months |

| Asymptomatic | Previous valve surgery |

| Age >18 and <85 years | Severe valve disease other than AS |

| Prepared to undergo AVR if symptoms develop | Persistent atrial fibrillation or flutter |

| Ability to perform bicycle exercise test | Severe asthma |

| History of heart failure | |

| Severe renal impairment eGFR <30 mL/min | |

| Planned AVR | |

| EF <40% | |

| Any absolute contraindication to CMR | |

| Contraindication to adenosine | |

| Other medical condition that limits life expectancy or precludes AVR | |

| Pregnancy |

AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CMR, cardiac MR; EF, extraction fraction; eGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; MI, myocardial infarction.

In addition, 20 asymptomatic controls without known cardiac disease will undergo baseline assessment to allow determination of age and sex-matched normal ranges for MPR, diffuse myocardial fibrosis and exercise capacity.

Primary outcome measures

Composite of typical AS symptoms necessitating referral for AVR, cardiovascular death and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; hospitalisation with any of heart failure, chest pain, syncope, arrhythmia or stroke) at 12 months (time to first event). Asymptomatic patients having AVR for other reasons (valve progression, positive exercise test) will be excluded from primary endpoint analysis.

Secondary outcome measures

Composite of AVR (for any reason) and MACE at 12 months (first event).

Composite of AVR and MACE during follow-up (first event).

Determinants of exercise capacity (age and sex corrected peak VO2) in AS.

Determinants of MPR in AS.

Predictors of symptom development in AS.

Predictors of progression of diffuse fibrosis and LV remodelling in AS at 12 months.

Predictors of progression in microvascular dysfunction (reduced MPR) in AS at 12 months.

Reproducibility of MPR measurement in AS (substudy).

Recruitment and data collection

Patients will be recruited from a number of regional hospitals, with testing performed at one of five tertiary cardiac centres in the UK with expertise in the management of AS and in CMR (Leicester, Leeds, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen; see figure 1). Patients will be identified from cardiology clinics, echocardiography and MRI reports. Suitable patients will be approached in outpatient clinics by a member of the clinical team and given a patient information sheet (PIS) if interested. Those who are not due in clinic in the near future will be posted a PIS with a reply form and stamped addressed envelope. An electronic case report form (e-CRF) will be used to collect study data, which has been developed by the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow. Access to the e-CRF will be restricted, with only authorised personnel able to make entries or amendments to patients’ data.

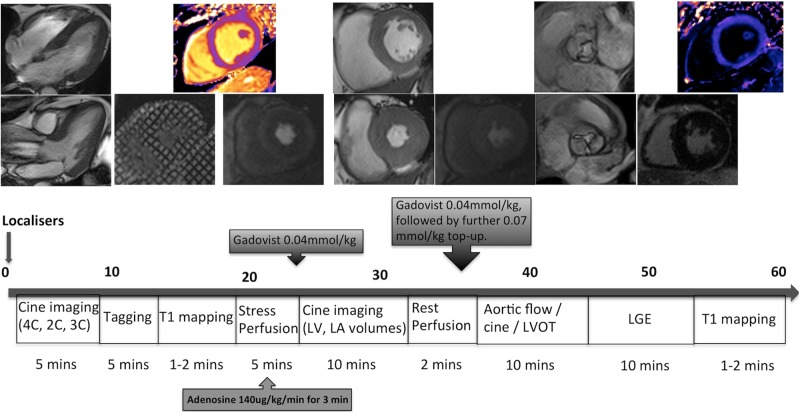

Figure 1.

Flow chart demonstrating study plan.

Baseline assessment

Written, informed-consent will be taken from all patients. Heart rate and blood pressure (BP) will be recorded and a resting ECG will be performed.

Venepuncture

A blood sample for clinical blood tests, including haematocrit for calculation of myocardial extracellular volume (ECV), will be drawn. An additional 20 mL of venous blood will be collected for biomarkers. These samples will be immediately transferred on ice to a centrifuge, where they will be centrifuged at 2000 rpm, for 20 min, at 4°C. Once separated, the plasma will be pipetted into cryotubes in aliquots and stored in a cryobox in an electronically monitored freezer at –80°C, for analysis at the end of the study.

Biobanking

With additional consent, a blood sample will be drawn and banked for prospective research studies. All tissue will be collected, stored and disposed of in accordance with the Codes of Practice as laid out by the Human Tissue Authority.

Echocardiography

This will be undertaken according to the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations to determine AS severity and grade diastolic dysfunction.35 At peak exercise, maximal peak and mean aortic valve velocity will be measured, allowing calculation of valve compliance.36

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

A symptom-limited maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test will be performed on a bicycle ergometer with workload increasing at 1 min intervals. Workload increments will be based on patient age, gender, height and weight.37 The test will be physician supervised and BP will be recorded at 2 min intervals. Indications for medical termination will be as previously published.36 Prior to the test initiation patients will be read the following statement: ‘Breathlessness is laboured or difficult breathing characterised by air hunger and an uncomfortable awareness of one’s own breathing.’ The test will be considered symptomatically positive if the patient stops prematurely due to limiting breathlessness, chest tightness or dizziness at <80% of predicted workload. Results of the cardiopulmonary exercise test will not be reported unless the responsible cardiologist would have performed an exercise test for clinical purposes.

Cardiac MR

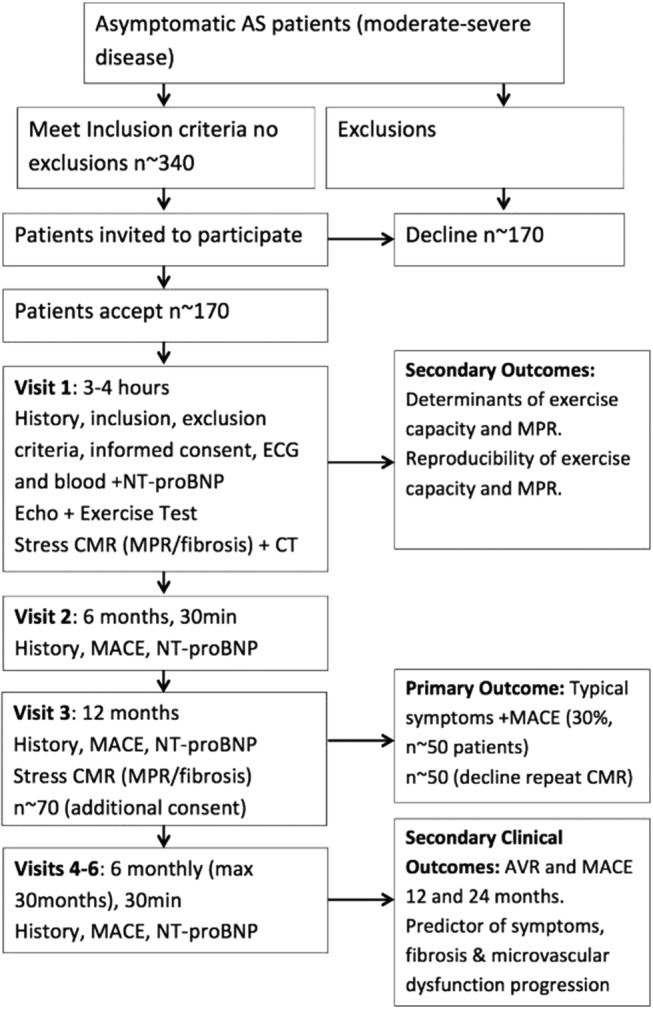

Patients will be imaged on 3 T CMR platforms because of the better signal intensity and limits of agreement of myocardial blood flow with microspheres and better tag persistence compared to 1.5 T, with similar LV function analysis. A comprehensive adenosine stress (140 µg/kg/min for 3 min) and rest perfusion study will be undertaken (figure 2), to determine: (1) LV mass and volumes/ejection fraction; (2) rest and stress myocardial blood flow and MPR; (3) LGE for focal fibrosis; (4) precontrast and postcontrast T1 mapping at a mid-ventricular level and (5) Tagging in three short axis slices.

Figure 2.

MRI protocol used (4/2/3C, 4/2/3 chamber; LA, left atrial; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract).

CMR analysis

The epicardium and endocardium will be contoured on the perfusion images, along with a region of interest in the LV blood pool, to generate signal intensity curves. The arterial input function corrected for signal saturation will be used for myocardial blood flow (MBF) quantification by model-independent deconvolution.38 Transmural MPR will be calculated by dividing hyperaemic blood flow by resting blood flow. Ten patients will undergo repeat adenosine stress CMR (within 10 days) to assess the reproducibility (coefficient of variation) of MPR in AS. Focal and diffuse fibrosis will be assessed using LGE and precontrast and postcontrast T1 mapping to estimate the myocardial ECV.39 Tagging will be analysed using InTag postprocessing toolbox (Creatis, Lyon, France) in OsiriX (Geneva, Switzerland).

At the 12-month visit, with additional consent, the rate of change in MPR will be assessed in those patients who have not developed symptoms. This will allow correlation of MPR with LV remodelling, diffuse and focal LV fibrosis development. All CMR scans will be analysed at the core lab (University of Leicester) by a single investigator blinded to all patient details.

CT coronary artery calcium scoring

The role of subclinical coronary artery disease in the progression to symptoms in asymptomatic AS is unclear. CT coronary artery calcium (CTCAC) scoring will be performed on a multidetector CT scanner with ECG gating, in a single breath-hold. Coronary artery calcification will be reported as present/absent and scored according to standard criteria to allow correlation of subclinical atherosclerosis in relation to MPR. CT scans will be analysed at the core lab in Leicester by a specialist cardiac radiologist. Reports will remain blinded except in the event of potentially life-threatening incidental findings and CTCAC >3 SDs above age-predicted values. The extent of AV calcification will also be assessed in relation to valve compliance and clinical outcome.

Follow-up

Patients will be followed up at 6 monthly intervals to a maximum of 30 months. The research team will contact patients by telephone just before the follow-up appointment is due, in order to optimise attendance, and travel costs will be covered for their follow-up visits if required. Each visit will include a history on development of any typical symptoms, admissions to hospital, prespecified MACE and venepuncture for NT-proBNP. For patients who report typical symptoms or MACE, the responsible clinician will be notified to consider referral for AVR. The 12-month visit will take place at the tertiary cardiac centres and if patients are asymptomatic, they will be invited to have repeat CMR as per baseline.

Event adjudication

All patients will be registered with the National Health Service (NHS) Information service or the Information Services division in Scotland to verify outcomes and acquire long-term data. Two independent cardiologists will judge clinical events for the primary outcome. Disagreement will be resolved by consensus and if necessary by a third independent clinician.

Statistical analysis

This will be performed under the supervision of IF at the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics. All patients recruited will have a minimum of 1 year of follow-up for the primary outcome. The relationship between MPR and exercise testing with 1-year outcome will be analysed using logistic regression. The MPR cut-point for predicting the primary outcome will be determined from receiver operating characteristic analysis and will be selected to match the sensitivity of exercise-induced symptoms. Paired comparisons of the specificities of the two approaches on the same dataset will be carried out using McNemar’s test. The prognostic value of exercise test symptoms at low workload and MPR individually and in combination will be assessed for the full follow-up period using Cox-regression analyses, testing the significance of MPR in the presence of exercise test data, NT-proBNP and by calculating and comparing c-statistics (discrimination), Hosmer Lemeshow statistics (calibration) and net reclassification indices (prognostic value). Predictors of MPR and VO2 will be assessed by univariate and multivariate regression analysis. Time to event data will be displayed using Kaplan-Meier curves and all model assumptions will be assessed using appropriate methods.

Power calculation

The study, with 170 participants will have 80% power (binomial test) to show that MPR has superior overall accuracy (assumed 85%) in predicting symptom onset, compared with the results of previous studies for exercise testing (76%), assuming an annual event rate of 29%.15

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The study will be conducted according to the principles of the Medical Research Council Good Clinical Practice guidelines, Declaration of Helsinki, Data Protection Act, NHS Research Governance and relevant local and national laws. All patients will provide written informed consent during their first visit, before any tests are carried out, and will have had at least 24 h to decide whether to participate or not prior to this.

Study organisation and oversight

The sponsor is the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust. A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) has been appointed and is responsible for the scientific and ethical conduct of the study. This consists of the independent chairman and two members, the chief investigator, two coinvestigators from the tertiary centres, a lay representative, representative of the Clinical Trials and Evaluation Unit and a representative of the sponsor. The study protocol and subsequent amendments have been approved by the TSC. A data monitoring committee was deemed not necessary given the observational design.

Study timetable

Ethics application was approved in December 2011. Study enrolment started in April 2012 and recruitment is expected to be completed in November 2013 with a further 12 months for follow-up, postprocessing and close-out of the study. The main study paper will be submitted within 6 months of study close-out.

Funding sources

The study has been funded by a grant from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR; Grant award number: NIHR-PDF 2011-04-51 Gerald P McCann). Additional support and resources for the study will be provided by the NIHR Leicester Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit and NIHR Comprehensive Local Research Networks.

Discussion

Limitations

The primary endpoint includes AVR for symptom development, which is subjective in nature. However, AVR by itself is deliberately not considered an endpoint due to the variability in clinical practice in referring severe but asymptomatic patients for surgery. Such patients will also be excluded from primary endpoint analysis. The presence of underlying coronary artery disease (CAD) may affect MPR and possibly symptom development. Although previous coronary artery bypass grafting/myocardial infraction with 6 months is an exclusion criteria, the patients will not undergo coronary angiography to exclude CAD. The possibility of CT coronary angiography was considered but the high radiation dose at the time of study planning, administration of intravenous contrast and β-blockers, was not felt to be justified in asymptomatic patients.

Anticipated health benefits

The study will address a number of limitations in previously published data, with the primary endpoint being driven by symptom development and MACE. The study should identify the strongest prognostic markers on which to base identification of asymptomatic patients with moderate-to-severe AS for consideration of early (before symptoms develop) AVR. The efficacy of such a strategy should be assessed in a prospective randomised controlled trial of early surgery in those with impaired MPR versus watchful waiting until symptom development.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AS is responsible for acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. IF and MJ-H are responsible for analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. JPG, CB, SN, BP, BW and NJS were involved in conception and design of the study and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JNK and AU were involved in acquisition of data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. GPM is responsible for the conception and design of the study, drafting and critically revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: NIHR grant number PDF 2011-04-51 Gerald P McCann.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study has full ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee East Midlands (REC reference 11/EM/0410).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bridgewater B, Kinsman R, Walton P, et al. Demonstrating quality: the sixth National Adult Cardiac Surgery database report. Henley-on-Thames: Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain & Ireland 2008

- 2.Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1231–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nkomo V, Gardin J, Skelton T, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:1005–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, et al. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:2111–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: the task force on the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007;28:230–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease). Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:e1–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carabello BA. Aortic valve replacement should be operated on before symptom onset. Circulation 2012;126:112–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah PK. Severe aortic stenosis should not be operated on before symptom onset. Circulation 2012;126:118–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCann GP, Steadman CD, Ray SG, et al. Managing the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis: randomised controlled trials of early surgery are overdue. Heart 2011;97:1119–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:611–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang DH, Park SJ, Rim JH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment in asymptomatic very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2010;121:1502–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenhek R, Zilberszac R, Schemper M, et al. Natural history of very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2010;121:151–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amato MC, Moffa PJ, Werner KE, et al. Treatment decision in asymptomatic aortic valve stenosis: role of exercise testing. Heart 2001;86:381–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancellotti P, Lebois F, Simon M, et al. Prognostic importance of quantitative exercise Doppler echocardiography in asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation 2005;112(Suppl 9):I377–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das P, Rimington H, Chambers J. Exercise testing to stratify risk in aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1309–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steadman CD, Ray S, Ng LL, et al. Natriuretic peptides in common valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2034–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das P. Determinants of symptoms and exercise capacity in aortic stenosis: a comparison of resting haemodynamics and valve compliance during dobutamine stress. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1254–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafique AM, Biner S, Ray I, et al. Meta-analysis of prognostic value of stress testing in patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:972–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2008;118:e523–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cioffi G, Faggiano P, Vizzardi E, et al. Prognostic effect of inappropriately high left ventricular mass in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Heart 2011;97:301–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupari M, Turto H, Lommi J. Left ventricular hypertrophy in aortic valve stenosis: preventive or promotive of systolic dysfunction and heart failure? Eur Heart J 2005;26:1790–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rost C, Korder S, Wasmeier G, et al. Sequential changes in myocardial function after valve replacement for aortic stenosis by speckle tracking echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11:584–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, et al. Midwall fibrosis is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajappan K, Rimoldi OE, Dutka DP, et al. Mechanisms of coronary microcirculatory dysfunction in patients with aortic stenosis and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Circulation 2002;105:470–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajappan K, Rimoldi OE, Camici PG, et al. Functional changes in coronary microcirculation after valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation 2003;107:3170–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flett AS, Sado DM, Quarta G, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in severe aortic stenosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;13:819–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munt BI, Legget ME, Healy NL, et al. Effects of aortic valve replacement on exercise duration and functional status in adults with valvular aortic stenosis. Can J Cardiol 1997;13:346–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krayenbuehl HP, Hess OM, Monrad ES, et al. Left ventricular myocardial structure in aortic valve disease before, intermediate, and late after aortic valve replacement. Circulation 1989;79:744–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azevedo CF, Nigri M, Higuchi ML, et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis quantification by histopathology and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with severe aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:278–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debl K, Djavidani B, Buchner S, et al. Delayed hyperenhancement in magnetic resonance imaging of left ventricular hypertrophy caused by aortic stenosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: visualisation of focal fibrosis. Heart 2006;92:1447–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weidemann F, Herrmann S, Stork S, et al. Impact of myocardial fibrosis in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2009;120:577–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shehata ML, Cheng S, Osman NF, et al. Myocardial tissue tagging with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2009;11:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandstede JJ, Johnson T, Harre K, et al. Cardiac systolic rotation and contraction before and after valve replacement for aortic stenosis: a myocardial tagging study using MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:953–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steadman CD, Jerosch-Herold M, Grundy B, et al. Determinants and functional significance of myocardial perfusion reserve in severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging 2012;5:182–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das P, Rimington H, Smeeton N, et al. Determinants of symptoms and exercise capacity in aortic stenosis: a comparison of resting haemodynamics and valve compliance during dobutamine stress. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1254–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasserman K, Hanson J, Sue D, et al. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. 3rd edn Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jerosch-Herold M, Swingen C, Seethamraju RT. Myocardial blood flow quantification with MRI by model-independent deconvolution. Med Phys 2002;29:886–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ugander M, Oki AJ, Hsu LY, et al. Extracellular volume imaging by magnetic resonance imaging provides insights into overt and sub-clinical myocardial pathology. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1268–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monin JL, Lancellotti P, Monchi M, et al. Risk score for predicting outcome in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation 2009;120:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.