Abstract

Cases of brucellosis were diagnosed in 3-month-old twins and their mother. An epidemiologic survey suggested that raw sheep or goat meat might be the source of Brucella melitensis infection. This finding implies that the increasing threat of brucellosis might affect low-risk persons in urban settings in China.

Keywords: brucellosis, bacteria, human infection, public health, urban setting, risk, China

Brucellosis, a zoonotic disease, causes severe pain and impairment in humans. In 2012, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) reported 39,515 new cases of human brucellosis, and this number is increasing by 10% each year. Generally, brucellosis is associated with persons who are occupationally in contact with Brucella spp.–infected animals or products (1,2). However, in this report, we present a cluster of cases of brucellosis in a family living in Guangzhou, China. These data illustrate a trend of human brucellosis threatening theoretically low-risk persons in an urban setting and suggest a need for eradicating or controlling Brucella spp.–infected animals and products in China.

Case Reports

Congenital brucellosis was diagnosed in patients 1 and 2, who were 3-month-old twins (Technical Appendix Table). They were prematurely delivered by cesarean section on July 6, 2012, at the Provincial Maternity and Child Care Center (Guangzhou, China). The boy (patient 1, Apgar score 9–10/1–10 min) had a birthweight of 2.3 kg, and the girl (patient 2, Apgar score 9–10/1–10 min) had a birthweight of 1.8 kg. They received standard care for preterm neonates at the hospital. They were discharged once their weight reached 2.5 kg; this happened for patient 1 at 3 weeks of age and for patient 2 at 4 weeks of age (July 29 and August 3, 2012, respectively).

On October 2, 2012, the boy was examined at the hospital for irregular fever up to 39°C. On October 9, he was readmitted to the hospital with a fever of 38°C and weight of 5.0 kg. Chest radiograph showed signs of increased bronchovascular shadows. Mezlocillin sodium and sulbactam sodium (4:1) and ribavirin were administered, but the patient did not improve. On the same day, the girl had a cough and low-level fever (37–37.5°C) but was not hospitalized. On October 16, B. melitensis was isolated from a blood culture from patient 1, in whom brucellosis with alveobronchiolitis, abnormal hepatic function, and moderate anemia were initially diagnosed when he was 3 months and 10 days of age.

On October 17, the twins were transferred to an infectious disease hospital, where they had extensive physical and laboratory examinations (Table 1). During 57 days of hospitalization, the boy received general and specific therapies for brucellosis. Brucellosis and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency were diagnosed in the girl, and she received appropriate treatment. At the time of discharge (December 12), the twins were well and without fever. They left the hospital for home care, which was supervised by a local general practitioner who provided rifampin and sulfamethoxazole for up to 6 weeks.

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory data on twin patients on admission to the infectious disease hospital.

| Variables* | Patient 1, twin boy | Patient 2, twin girl | Reference range (children)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature, °C | 38 | 37.0 | 36–37 |

| Pulse, beats/min | 128 | 128b | 120 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 34 | 36 | 30–35 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | 76/42 | 76/45 | 80/48 |

| Weight, kg | 5.7 | 5.6 | |

| Erythrocyte count, cells/L | 4.99 × 1012 | 4.69 × 1012 | 3.5–5.5 × 1012 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 85 | 89 | 120–160 |

| Hematocrit, % | 26.3 | 27.5 | 40–50 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 5 | No record | <10 |

| Leukocyte count, cells/L | 7 × 109 | 8.51 × 109 | 4.0–10.0 × 109 |

| Differential count, % | |||

| Neutrophils | 18.8 | 10.7 | 50–75 |

| Eosnophils | 3 | 1.1 | 0.5–5 |

| Basophiles | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0–1.0 |

| Lymphocytes | 74.3 | 83.9 | 20–40 |

| Monocytes | 3.7 | 4 | 3.0–10.0 |

| Platelet count, per L | 462 × 109 | 456 × 109 | 100–300 × 109 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 103 | 135.4 | 135–145 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 33 | No record | 3.4–4.8 |

| Glucose 6-dehydrogenase, U/L | 4,254 | 1,363 | ≥2,500 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 356 | 322 | 100–380 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 31 | 48 | 5–40 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 54 | 64 | 5–40 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 508 | 642 | 30–390 |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/L | 8.49 | 5.17 | 5.10–22.2 |

| Total protein, g/L | 51 | 49 | 60–68 |

| Albumin, g/L | 37 | 40 | 35–55 |

| Globulin, g/L | 14 | 9 | 20–35 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.03–5 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 49 | 203 | 24–194 |

| Creatine kinase-MB, U/L | 32 | 25 | 0–25 |

| Brucella antibody titer, SAT | 400 | 800 | <100 |

| Blood culture | B. melitensis | B. melitensis | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | Negative | |

| Antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen, IU/L | 6.77 | Negative | |

| Hepatitis B e antigen | Negative | Negative | |

| EBV IgA | Negative | Negative | |

| Cytomegalovirus IgM | Negative | Negative | |

| Herpes simplex virus 1, 2 IgM | Negative | Negative | |

| Influenza virus A + B antigens | Negative | Negative | |

| Mycoplasma IgM | Negative | Negative | |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM | Negative | Negative | |

| Toxoplasma IgM | Negative | Negative |

*Major items are presented from clinical testing. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus. †The ranges used at this hospital are not all for children, and may not be appropriate for the twin patients. The values may be affected by the laboratory methods in different hospitals.

Patient 3 (the mother of patients 1 and 2), a 31-year-old woman who was admitted to a hospital on July 4, 2012 for threatened premature labor at 34 weeks and 2 days’ gestation. Chorioamnionitis phase I was diagnosed that day. On July 6, the patient gave birth to twins through a uterine lower segment cesarean section due to early rupture of the amniotic membrane. Postnatally, the mother was in generally good clinical condition without specific complaint and was discharged for home care on July 11. When Brucella infection was diagnosed in her son (patient 1), she was hospitalized for suspected Brucella infection (Technical Appendix Table). Brucellosis was diagnosed, and she was treated as an outpatient with a 4-week course of rifampin and doxycycline and 1-week course of streptomycin. Her symptoms of brucellosis rapidly improved.

Serologic and bacteriologic tests were conducted for diagnosis of Brucella infection. On October 17, 2012, blood samples were taken from all 6 members of the patients’ family. By standard tube agglutination test, the twins and their mother tested positive for Brucella antibodies with titers of 400 (twins) and 800 (mother), whereas results for the twins’ father and grandparents were negative. Brucella antibodies from the twins’ blood samples were detected 3 times with titers of 400, 200, and 200 on November 10, 18, and 29, respectively. Plasma from the twins’ cord blood tested positive by a rose bengal plate test, but results were indeterminate or negative by standard tube agglutination test (titer <50). Samples from patients 1–3 were collected on October 17, and on October 25, after 8 days of blood cultures on commercial agar plates 3 Brucella strains were isolated. A Brucella sp. was repeatedly isolated in blood samples collected on November 10 but not in samples collected on November 18 and 29, after the patients were treated with rifampin. The mother’s breast milk was collected before and after she was treated for brucellosis, and Brucella sp. was not isolated from these samples.

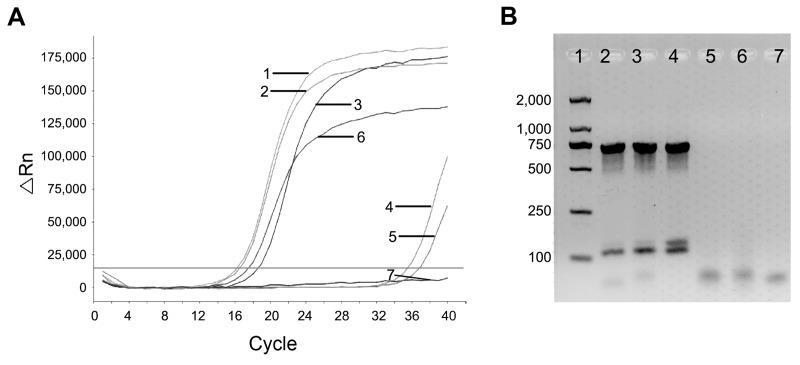

Brucella DNA was tested by quantitative PCR of blood cultures from 3 patients, from patients’ cord blood, and from a positive control (Figure 1, panel A). Additionally, the specific DNA bands for B. melitensis were identified from each patient’s blood culture by an abbreviated B. abortus, melitensis, ovis, and suis (AMOS) PCR (3) but were not observed from the twins’ cord blood, possibly due to low levels of Brucella DNA (Figure 1, panel B).

Figure 1.

Detection and identification of Brucella DNA. A) Detection of Brucella DNA by quantitative PCR. Numbers indicate amplification curves with cycle threshold (Ct) values representative of samples. Curve 1, sample from patient 1 with 16 Ct value; curve 2, sample from patient 2 with 16 Ct; curve 3, sample from patient 3 with 17 Ct; curve 4, stem cells of cord blood from patient 1 with 34 Ct; curve 5, stem cells of cord blood from patient 2 with 34.5 Ct; curve 6, positive control with 18 Ct, curve 7, negative control with no Ct. B) Amplification of Brucella DNA by AMOS-PCR. Numbers indicate the amplified DNA bands representative of samples. Lane 1, DNA molecular weight marker, values along the left side are base pairs; lane 2, sample from patient 1; lane 3, sample from patient 2; lane 4, sample from patient 3; lane 5, stem cells from cord blood of patient 1; lane 6, stem cells from cord blood of patient 2; lane 7, negative control.

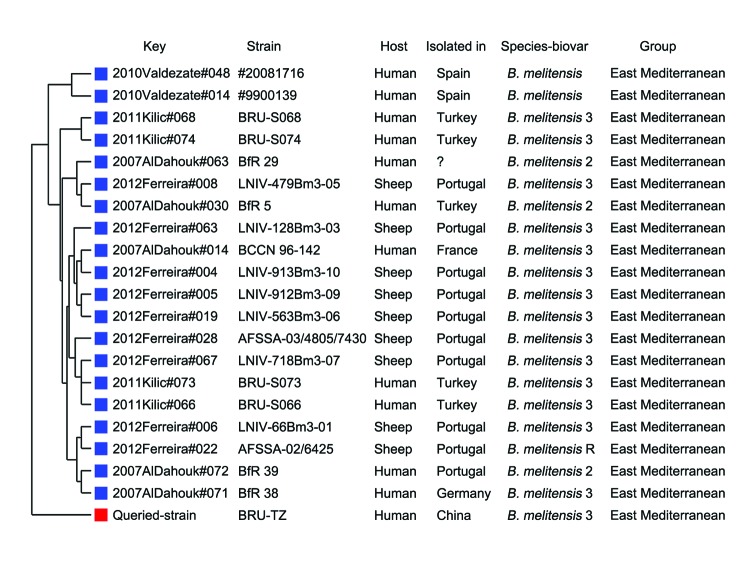

Bacterial isolates were characterized as B. melitensis biotype 3 (Table 2) (4). By multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of 16 samples (5), these Brucella isolates from the twins and their mother were genetically identical. They were all genotyped as 16 loci, with variable number of tandem repeats of 1 5 3 13 2 3 3 2 6 22 9 6 9 11 4 5, which was phylogenetically closer to #20081716 and #9900139 strains prevalent in Spain (Figure 2) but differed from strains prevalent in Kyrgyzstan (6).

Table 2. Bacteriological and biochemical features of Brucella strains.

| Strain | TZ (twin boy) | TS (twin girl) | ML (mother) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 requirement | – | – | – |

| H2S production |

– |

– |

– |

| Dye inhibition* | |||

| Thionin | + | + | + |

| Basic fuchsin |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Mono-specific anti-serum agglutination† | |||

| A | + | + | + |

| M | + | + | + |

| R |

– |

– |

– |

| Lysis test by Brucella spp. phage‡ | |||

| Tb104 | – | – | – |

| Tb | – | – | – |

| Wb | ± | ± | ± |

| BK2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Identification | |||

| Species | B. melitensis | B. melitensis | B. melitensis |

| Biovar | 3 | 3 | 3 |

*A final concentration of 20 μg/mL dyes was used in the testing (4). †The bacterial isolate was tested for agglutination by mono-specific anti-serum samples to Brucella antigens A, M, and R (rough), respectively. ‡Bacterial isolate was tested for lysis by specific Brucella phages of Tb, Wb, and BK2.

Figure 2.

Genetic relationship between the strain isolated in this study (BRU-TZ) and other Brucella melitensis strains. The variable number of tandem repeats were obtained for phylogenetic analysis at multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis bank version-4 (http://mlva.u-psud.fr) (5,6). The phylogenetic tree was plotted on the differences in variable number of tandem repeats at 16 loci obtained by multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis.

Conclusions

Patients with brucellosis usually have occupations that involve interaction with animals or clinical or laboratory veterinary work. There are reports of human brucellosis related to blood transfusion (7), bone marrow transplantation (8), transplacental transmission (9), breast feeding (10), or sexual activity (11). In this study, a cluster of brucellosis was identified in 3 patients from a 6-member family. However, the mother and other family members denied having risk factors associated with brucellosis. During the mother’s pregnancy, she had fever and aching bones, while the grandmother occasionally prepared steamed stuffed buns containing raw sheep or goat meat, which reportedly were bought at the supermarket or local butcher’s shop. Raw meat might therefore constitute the source of the Brucella infection.

In recent years human brucellosis cases have spread quickly from rural to urban areas and increased sharply in persons in China who do not fit into standard risk categories. Guangzhou, a major city in southern China, is located far away from the Brucella-endemic areas of northern China but has recorded increasing numbers of human brucellosis: >60 cases in the past 5 years (China CDC, unpub. data). Live animals and raw meat products are frequently transported across the whole country, and cases of brucellosis have been recorded in all regions of the country (12). About 85% of brucellosis cases have been attributed to B. melitensis from infected sheep or goats (12,13), which put ordinarily low-risk persons at much higher risk when they consumed or handled infected animal meat and milk (14). The increasing numbers of cases of brucellosis indicates that the strategy of vaccination and quarantine for infected animals has failed in China. One possible reason is the limited efficacy of the current vaccines (2,15), but a primary reason is that the policies for eradication and control of Brucella-infected animals and their products have not been adequately implemented.

Time points of clinical examination for the 3 patients with brucellosis reviewed in this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians who provided clinical information about cases, Guangzhou Stem Cell Bank for providing the reserved stem cells of the twins’ cord blood, Yuming Zhang (for reviewing patients’ cases, and Jean-Pierre Allain for his helpful revisions and comments.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program No. 2010CB530204) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31100657). The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report.

Biography

Dr Chen is affiliated with Guangzhou CDC. His primary research interests are surveillance for emerging and re-emerging diseases in Guangzhou, China.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Chen S, Zhang H, Liu X, Wang W, Hou S, Li T, Zhao S, Yang Z, Li C. Increasing threat of brucellosis to low-risk persons in urban settings, China. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Jan [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2001.130324

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL. Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:775–86. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorvel JP. Brucella: a Mr “Hide” converted into Dr Jekyll. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1010–3. 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2660–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbel MJ. Identification of dye-sensitive strains of Brucella melitensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1066–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Dahouk S, Flèche PL, Nöckler K, Jacques I, Grayon M, Scholz HC, et al. Evaluation of Brucella MLVA typing for human brucellosis. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;69:137–45. 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasymbekov J, Imanseitov J, Ballif M, Schürch N, Paniga S, Pilo P, et al. Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic susceptibility of livestock Brucella melitensis isolates from Naryn Oblast, Kyrgyzstan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2047. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Economidou J, Kalafatas P, Vatopoulou D, Petropoulou D, Kattamis C. Brucellosis in 2 thalassaemic patients infected by blood transfusions from the same donor. Acta Haematol. 1976;55:244–9. 10.1159/000208021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naparstek E, Block CS, Slavin S. Transmission of brucellosis by bone marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1982;319:574–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer R, Amitai Y, Geist M, Shimonovitz S, Herzog N, Reiss A, et al. Neonatal brucellosis possibly transmitted during delivery. Lancet. 1991;338:127–8. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90128-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palanduz A, Palanduz S, Güler K, Güler N. Brucellosis in a mother and her young infant: probable transmission by breast milk. Int J Infect Dis. 2000;4:55–6. 10.1016/S1201-9712(00)90068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer E, Sidi Y, Smolen G, Banai M, Bardenstein S, Schwartz E. Sexually transmitted brucellosis in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:e12–5. 10.1086/653608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang WY, Guo WD, Sun SH, Jiang JF, Sun HL, Li SL, et al. Human brucellosis, Inner Mongolia, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:2001–3. 10.3201/eid1612.091081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deqiu S, Donglou X, Jiming Y. Epidemiology and control of brucellosis in China. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90:165–82. 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00252-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luk S, To WK. Diagnostic challenges of human brucellosis in Hong Kong: a case series in 2 regional hospitals. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu J, Wang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Wang Y, Qiao J, et al. Characterization of periplasmic protein BP26 epitopes of Brucella melitensis reacting with murine monoclonal and sheep antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34246. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time points of clinical examination for the 3 patients with brucellosis reviewed in this article.