Abstract

Background:

Early detection of skin cancers by screening could be very beneficial to decrease their morbidity or mortality. There is limited study about skin cancer screening in Iran.

Aim:

This essay was planned as a pilot skin cancer screening campaign in Tehran, Iran to evaluate its profit and failure and further design large-scale screening program more definitely.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty one public health centers of Shahid Beheshti Medical University were selected in different areas of Tehran. The project was announced via media and invited all the people above 40 years old to come for the whole-body skin examination in a one-week period. Patients with any suspected lesions were referred to the dermatology clinics of the university.

Results:

1314 patients, 194 males (14.8%) and 120 females (85.2%), with mean age of 51.81 ± 10.28 years participated in this screening campaign. Physicians found suspected lesions in 182 (13.85%) of participants. The diagnosis of skin cancer was confirmed in 15 (1.14%) patients. These malignancies included 10 (0.76%) cases of basal cell carcinoma, 2 (0.15%) cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 3 (0.23%) cases of malignant melanoma.

Conclusion:

Skin cancer screening seems to be valuable to detect skin malignancies in their early course. Regarding the considerable amount of facilities needed to perform skin cancer screening program, it might be more beneficial to perform the targeted screening programs for the high-risk groups or emphasis more on public education of skin cancer risk factors and their early signs.

Keywords: Basal cell carcinoma, cost-effective, malignant melanoma, skin cancer screening, squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

What was known?

There is limited data upon skin cancer screening program in western Asia region and especially Iran.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the white population worldwide. The two most common variants are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); regardless of their low mortality rates, these tumors can provoke severe consequence as a result of their treatment. The third most frequent skin cancer type, malignant melanoma (MM), has a more destructive behavior and accordingly a poor prognosis; malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 75% of all deaths from skin cancer.[1,2] The major modality used for secondary prevention is skin cancer screening.[3] Skin cancer screening includes the complete cutaneous examination and 2-3 minute visual inspection of the skin. There is strong data that whole-body clinical skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanoma and, as a result, screening would reduce melanoma mortality.[4] In US and other countries such as Australia there are some skin cancer education and screening programs.[5,6] However, some studies debate on the effective and beneficial method of skin cancer screening as mass screening or high risk group screening and the real impact of skin cancer screening result on the society health.[7]

In Iran, there are limited studies about prevalence and incidence of skin cancers. The estimated incidence rate is 10 to 15 new cases per 100,000 populations.[8,9] We found no published report of skin cancer screening in Iran. Therefore, this study was planned as a pilot one-week skin cancer screening campaign in Tehran, Iran to evaluate its profit and failure and design further large-scale screening program more definitely.

Materials and Methods

This study was planned as a skin cancer screening campaign in the public health centers of Shahid Beheshti Medical University in a one-week period in Tehran, Iran. We applied for the collaboration of the public health centers in Tehran as the location of this screening program. These health centers are generally under supervision of Medical Universities. The usual services provided in these centers include prenatal and pediatric care, women health, vaccination, health education, environmental or occupational health, etc., Due to distribution of these centers in different areas of Tehran, we discussed with the health deputy of the university for the collaboration of these health centers in this screening campaign and finally, thirty one public health centers were selected in different areas of Tehran.

Physicians and health staffs of these health centers were volunteered to cooperate in this study. Due to cultural and religious belief in our country, some female participants might be reluctant to be examined by male physicians. In this regard, we select a male physician and female health staff or vice versa in each center to avoid any limitation in examination of the female participants. Practical information upon skin cancer risk factors and its early symptoms or signs along with any needed guideline of this screening project provided to them in a two-day course by an expert board certified dermatologist. An illustrated educational pamphlet in the case of the risk factors especially sun exposure, ways of prevention and early detection of skin cancer published and distributed in the health centers for general patient education. The project was announced via media, local newspaper and brochures. We invited all people over 40 years old to the mentioned health centers for complete skin examination in a one-week period on October 2008. We emphasized in these pamphlets and brochures that any bizarre or asymmetric skin lesion especially with change in shape, color and size might be important for screening. Moreover, it has been advocated that any skin erosion or ulcer remained unimproved after one month should be examined by physicians.

The participants would have undergone the whole-body skin examination by the trained physicians or health staffs. Any lesion with bizarre or asymmetric shape, uneven color, increasing size, resistant ulcers or erosions considered as suspicious. Patients with any suspected lesions were referred to the specialized dermatology clinics of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for further evaluation of their lesions. All the participants were instructed about the study, and they signed the informed consent forms. This essay was approved by the ethics committee of our center. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

A board certified dermatologist performed the whole-body skin examination for the referred patients and further evaluation particularly skin biopsy was done whenever needed. The skin examination was done by visual inspection and use of hand lens in the setting of proper lighting. The alarming signs including bizarre or asymmetric shape, uneven color, increasing size, resistant ulcers or erosions were considered for decision to perform skin biopsy. We could not use dermatoscope because of some limitation in the facilities. In the case of confirmed malignancies, the suitable treatment would be provided for the patients in the dermatology ward or referred to the proper department. All the data registered and the related questionnaires were completed. After gathering the data, statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS 16.0.0. (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In a one-week period of screening, 1314 patients, 194 males (14.8%) and 1120 females (85.2%), with mean age of 51.81 ± 10.28 years were attended the allied health centers and underwent the whole-body skin examination.

Regarding the considerable attendance of female volunteers, most of them had indoor occupation especially being housewives. More than 85% of participants show Fitzpatrick skin type III or IV. We found multiple freckling in about 28% of participants. We had the data of the number of melanocytic nevi in 92.9% of the participants. 25% of them had less than 3 melanocytic lesions and 25% had more than 10 lesions. Less than one percent of the participant had the positive personal history of skin cancer. We have found the personal history of non-skin cancers in 14 (1.1%) of participants. These were ovarian, prostate, breast and gastrointestinal carcinoma. 19.1% of participants had the positive family history of the non-skin cancers.

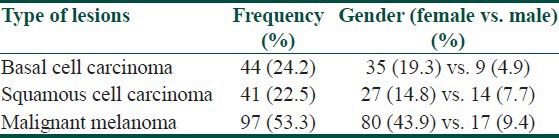

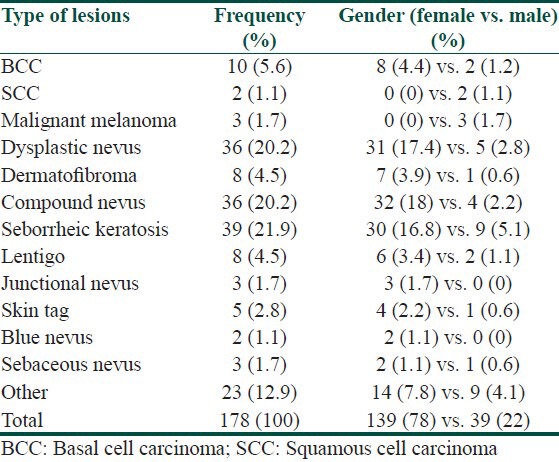

Physicians found suspected lesions in 182 (13.85%) of participants [142 (78%) females and 40 (22%) males] with possible diagnosis of BCC, SCC or malignant melanoma which were located mostly on the head, neck and trunk [Table 1]. These participants with suspected lesions were referred to the allied dermatology clinics of the university. Four participants refused to attend the dermatology clinics due to unknown reasons. We have evaluated 178 referred participants in our specialized dermatology clinics. All these patients underwent the whole-body skin examination by a board certified dermatologist and skin biopsy performed in 115 patients for the histopathological examination. Table 2 shows the final diagnosis of suspected malignant skin lesions referred from the health centers.

Table 1.

Clinical diagnosis of suspected lesions by primary physician

Table 2.

Final diagnosis of the suspected lesions

The diagnosis of skin cancer was finally confirmed by histopathology evaluation in 15 (1.14%) patients out of 1314 volunteers who participated in this skin cancer screening program [Figures 1 and 2]. These malignancies include 10 (0.76%) cases of BCC, 2 (0.15%) cases of SCC and 3 (0.23%) cases of malignant melanoma. One patient with malignant melanoma showed positive personal history of skin cancer. Two patients with BCC had positive personal history of breast and gastrointestinal cancers but no family history of skin and non-skin cancer found in these patients. Thirty six (2.74%) cases of dysplastic nevus were also diagnosed in this study. In the case of confirmed malignancies, the proper treatment provided for the patients in the dermatology ward or surgery department.

Figure 1.

A morphoeic basal cell carcinoma found on the eyebrow of a middle-age man

Figure 2.

Squamous cell carcinoma on the ear in an elderly man

We found no significant difference in the number of common moles, multiple freckling, family history of skin and non-skin cancers between skin-cancer diagnosed patients and other participants. Outdoor occupations and personal history of non-skin cancers was significantly higher in skin cancer diagnosed patients (P < 0.05, Chi-square test).

Discussion

Early diagnosis of skin cancer is very crucial to improve the prognosis, for best treatment results, and increase the quality of life of the patient. In this regard, there are many studies upon skin cancer screening with valuable results upon the importance of early detection of skin malignancies.[10,11,12,13] However, there is no strong evidence to establish whether there is a decrease in mortality due to regular physical examination of the skin.[7,14,15]

In this study, we find 15 cases (10 BBC, 2 SCC and 2 malignant melanoma) of skin cancer. Most of the participants in this campaign were housewives women and this could be due to the working hours of the public health centers that caused less attendance of male participants or those with outdoor jobs. If we could extend the active daily hours of screening to the evening, we could probably detect more skin cancers. Regarding the high population of Tehran, it would better screen more people or extend the campaign period to avoid this selection or estimating bias. Unfortunately, we could not improve these biases because of our limited facilities. However, this campaign was planned as pilot skin cancer screening program in Tehran and its results and limitation could help us to design the large-scale screening program more definitely.

There are different methods of skin cancer screening including population-based or targeted screening. Planning of a population-based or mass skin cancer screening program needed considerable cooperation of different sectors including dermatology or health departments and it need substantial facilities for the project setting, announcement, training of the volunteered health staff, their remunerations and further diagnostic or treatment measure for the participants. Well-trained physicians should be employed in order to reduce the false positive diagnosis and it may have great financial impact on the health care system. Moreover, the current evidence seems to be insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of mass screening for skin cancer.[7,15,16] Therefore, it might be more practical to perform the targeted screening programs for the high-risk groups such as patients with organ transplantation or those with the history of skin cancer or outdoor occupations.[17,18]

The media campaign increased the population awareness of skin cancers, promoted effective sun protection and make known the dangers of excessive UV-exposures. More educational activities for both patients and physicians regarding the skin cancer risk factors and their early signs and symptoms might be more beneficial and cost-effective to decrease the skin cancer mortality and morbidity.[19,20]

To the best of our knowledge, there was no similar study in Iran to perform skin cancer screening and this study provides us useful information upon the profit and failure of a screening program. Another limitation of this study was lack of comparison between different methods of skin cancer screening such as targeted or mass screening to provide more exact data upon the efficacy and cost-benefit of different methods of skin cancer screening. Therefore, further controlled study could be beneficial to elucidate the more practical and cost-effective method of skin cancer screening in our country.

What is new?

This study gives us many practical clues to plan and perform large-scale skin cancer screening better.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate all cooperation of the health deputy of Shahid Beheshti Medical University. We also thank Dr. Reza F Ghohestani for his kind guidance for development of this essay.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Skin Research Center

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Gallagher RP. Sunscreens in melanoma and skin cancer prevention. CMAJ. 2005;173:244–5. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uliasz A, Lebwohl M. Patient education and regular surveillance results in earlier diagnosis of second primary melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:575–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirsner RS, Federman DG. The rationale for skin cancer screening and prevention. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4:1279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, Youl P, English D. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:450–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill L, Ferrini RL. Skin cancer prevention and screening: Summary of the American college of preventive Medicine's practice policy statements. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:232–5. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theobald T, Marks R, Hill D, Dorevitch A. “Goodbye Sunshine”: Effects of a television program about melanoma on beliefs, behavior, and melanoma thickness. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:717–23. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopes-Kerr CP. Selections from current literature: Screening for skin cancer: Sense or nonsense? Fam Pract. 2002;19:112–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noorbala MT, Kafaie P. Analysis of 15 years of skin cancer in central Iran (Yazd) Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somi MH, Farhang S, Mirinezhad SK, Naghashi S, Seif-Farshad M, Golzari M. Cancer in east Azerbaijan, Iran: Results of a population-based cancer registry. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:327–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolognia JL, Berwick M, Fine JA. Complete follow-up and evaluation of a skin cancer screening in Connecticut. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6 Pt 1):1098–106. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70340-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelberg D, Gallagher RP, Rivers JK. Follow-up and evaluation of skin cancer screening in British Columbia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krol S, Keijser LM, van der Rhee HJ, Welvaart K. Screening for skin cancer in the Netherlands. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:317–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagano T, Ueda M, Suzuki T, Naruse K, Nakamura T, Taguchi M, et al. Skin cancer screening in Okinawa, Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1999;19:161–5. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(98)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoorob R, Anderson R, Cefalu C, Sidani M. Cancer screening guidelines. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1101–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh HK, Geller AC, Miller DR, Lew RA. Can screening for melanoma and skin cancer save lives? Dermatol Clin. 1991;9:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Screening for skin cancer: U. S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:188–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katris P, Donovan RJ, Gray BN. The use of targeted and non-targeted advertising to enrich skin cancer screening samples. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swetter SM, Waddell BL, Vazquez MD, Khosravi VS. Increased effectiveness of targeted skin cancer screening in the veterans affairs population of northern California. Prev Med. 2003;36:164–71. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carli P, De Giorgi V, Giannotti B, Seidenari S, Pellacani G, Peris K, et al. Skin cancer day in Italy: Method of referral to open access clinics and tumor prevalence in the examined population. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:76–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikkels AF, Nikkels-Tassoudji N, Jerusalem-Noury E, Sandman-Lobusch H, Sproten G, Zeimers G, et al. Skin cancer screening campaign in the German speaking community of Belgium. Acta Clin Belg. 2004;59:194–8. doi: 10.1179/acb.2004.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]