Abstract

Chronic paronychia is an inflammatory disorder of the nail folds of a toe or finger presenting as redness, tenderness, and swelling. It is recalcitrant dermatoses seen commonly in housewives and housemaids. It is a multifactorial inflammatory reaction of the proximal nail fold to irritants and allergens. Repeated bouts of inflammation lead to fibrosis of proximal nail fold with poor generation of cuticle, which in turn exposes the nail further to irritants and allergens. Thus, general preventive measures form cornerstone of the therapy. Though previously anti-fungals were the mainstay of therapy, topical steroid creams have been found to be more effective in the treatment of chronic paronychia. In recalcitrant cases, surgical treatment may be resorted to, which includes en bloc excision of the proximal nail fold or an eponychial marsupialization, with or without nail plate removal. Newer therapies and surgical modalities are being employed in the management of chronic paronychia. In this overview, we review recent epidemiological studies, present current thinking on the pathophysiology leading to chronic paronychia, discuss the challenges chronic paronychia presents, and recommend a commonsense approach to management.

Keywords: Chronic paronychia, en bloc excision of nail fold, hand dermatitis

Introduction

What was known?

Chronic paronychia was considered a form of fungal infection affecting the nail folds with anti-fungals being the mainstay of treatment. Surgical management like eponychial marsupialization and en bloc excision of nail fold was done in recalcitrant cases without nail plate removal.

Chronic paronychia is an inflammatory recalcitrant disorder affecting the nail folds. It can be defined as an inflammation lasting for more than 6 weeks and involving one or more of the three nail folds (one proximal and two lateral).[1] This review aims to throw a light on the current concepts in etiopathogenesis of chronic paronychia and brings in detail the past and present management strategies with special focus on newer therapies.

Structure of nail

The nail is a complex unit composed of five major modified cutaneous structures: The nail matrix, nail plate, nail bed, cuticle (eponychium), and nail folds.[2] The nail bed, which consists of 2 portions, is primarily involved in the production, migration, and maintenance of the nail. The proximal portion, called the germinal matrix, contains active cells that are responsible for generating new nail. Damage to the germinal matrix results in malformed nails. The distal portion, the sterile matrix, adds thickness, bulk, and strength to the nail. The nail arises from a mild proximal depression called the proximal nail fold. The nail divides the nail fold into 2 components: The dorsal roof and the ventral floor, both of which contain germinal matrices. Cuticle is an outgrowth of the proximal nail fold (PNF) and is situated between the skin of the digit and the nail plate, fusing these structures together. This configuration provides a waterproof seal from external irritants, allergens, and pathogens. In chronic paronychia, this seal is broken; the irritants enter the space thus created.

Clinical features

The patient presents with complaint of redness, tenderness, swelling, fluid under the nail folds, and thick discolored nail [Figure 1]. Morphologically, it is characterized by induration and rounding off of the paronychium, recurring episodes of acute eponychial inflammation and drainage. Nail plate may show thickening and longitudinal grooving. Onychomadesis, transverse striation, pitting, hypertrophy can be present and are probably due to inflammation of nail matrix.[3] Nail plate may present a green discoloration of its lateral margins due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization.

Figure 1.

A case of paronychia with rounding off of peronychium and thick, discoloured nails

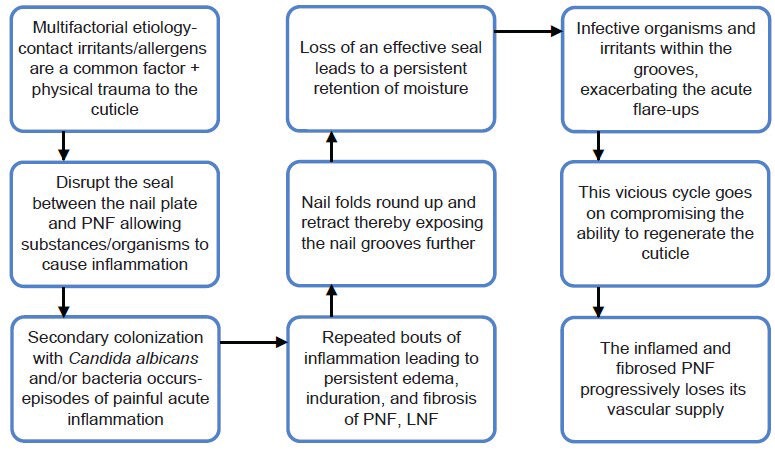

Pathogenesis

Repeated bouts of inflammation, persistent edema, induration, and fibrosis of proximal and lateral nail folds causes the nail folds to round up and retract, thereby exposing the nail grooves further. This loss of an effective seal leads to a persistent retention of moisture, infective organisms and irritants within the grooves, in turn exacerbating the acute flare-ups. This vicious cycle goes on, compromising the ability to regenerate the cuticle. The inflamed and fibrosed PNF progressively loses its vascular supply [Figure 2]. This is responsible for failure of medical treatment measures. Topical drugs fail to penetrate chronically inflamed skin, and systemic drugs cannot be delivered to areas of decreased vascular supply.[4]

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of chronic paronychia

Etiology

It has a complex pathogenesis and is caused by multifactorial damage to the cuticle, thereby exposing the nail fold and the nail groove.[5] Previously, it was believed that chronic paronychia is caused by Candida.[6] However, recent data reveals that it is a form of hand dermatitis caused by environmental exposure. Candida is often isolated; however, in many cases, Candida disappears when the physiologic barrier is restored.[7] Hence, the recent view holds that chronic paronychia is not a mycotic disease but an eczematous condition with a multifactorial etiology. For this reason, topical and systemic steroids may be used successfully, whereas systemic anti-fungals are of little value. Tosti et al.[7] discovered that topical steroids are more effective than systemic anti-fungals in the treatment of chronic paronychia. Although Candida was frequently isolated from the PNF of their patients with chronic paronychia, Candida eradication was not associated with clinical cure in most patients.

In a study conducted by Rigopoulos D et al.,[8] tacrolimus 1% ointment and betamethasone 17-valerate cream was found to be more effective in patients of chronic paronychia than just emollient application, confirming allergens and irritants have indeed an important contribution to the pathogenesis of chronic paronychia.

Chronic paronychia commonly afflicts house and office cleaners, laundry workers, food handlers, cooks, dishwashers, bartenders, chefs, nurses, swimmers, diabetes, and patients on HIV-ART. Hypersensitivity to foodstuff is responsible for an increased incidence in food handlers.[9]

There are many rare causes of chronic paronychia, which should always be kept in mind and some of which include the following:

Infections (Bacterial, mycobacterial, or viral)

Raynaud's disease

Metastatic cancer, subungual melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma. Benign and malignant neoplasms should always be excluded when chronic paronychia does not respond to conventional treatment

Papulosquamous disorders like psoriasis, vesicobullous disorders-pemphigus

Drug toxicity from medications such as retinoids, epidermal growth factor-receptor inhibitors (cetuximab), and protease inhibitors. Indinavir- induces retinoid-like effects and remains the most frequent cause of chronic paronychia in patients with HIV disease. Retinoids also induce chronic paronychia. The mechanism can be -nail fragility and minor trauma by small nail fragments.[10] Paronychia has also been reported in patients taking cetuximab (Erbitux), an anti-epidermal growth factor-receptor (EGFR) antibody used in the treatment of solid tumors.[11]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic paronychia includes squamous cell carcinoma of the nail, malignant melanoma, metastases from malignant tumors. The clinician should consider the possibility of the carcinoma when a chronic inflammatory process is unresponsive to treatment. Any suspicion for the aforementioned entities should prompt biopsy.

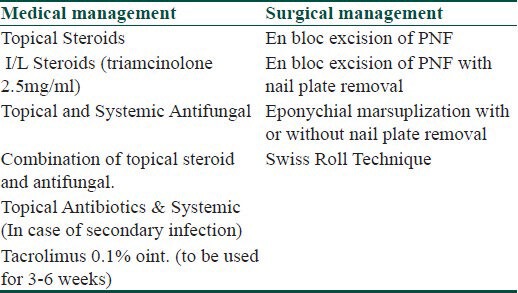

Treatment of chronic paronychia

Various treatment options for management of chronic paronychia have been enlisted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment options for management of chronic paronychia

General measures

These measures help in prevention as well as work synergistically with other active measures in improving the healing time and decreasing further recurrences. The basic aim is avoidance of aggravating factors and minimizing further injury by reducing the manipulation of the nail. The former may be achieved by avoiding exposure to moist environments and contact irritants such as soaps and detergents. The affected area should be kept dry, and moisturizers should be applied after washing hands. Rubber gloves should be used, preferably with inner cotton glove or cotton liners while performing any work with probable exposure to irritants.[12] Further injury may be minimized by keeping the nails short and avoiding any manipulation of the nail, such as manicuring, finger sucking, or self attempt to incise and drain the lesion. The footwear should be properly chosen to avoid unnecessary damage to the nail. The patients with diabetes should maintain a strict glycemic control.[12]

Medical management of chronic paronychia

Initially, organisms such as Candida and intestinal bacteria were causally related to this condition.[13,14] Thus, anti-fungals played an important role in the management of chronic paronychia in the past, and several studies using topical or systemic anti-fungals have reported encouraging results. Wong et al.[15] compared the therapeutic effect of ketoconazole tablets and econazole lotion in the treatment of chronic paronychia and found them comparable in efficacy. However, they continued to isolate Candida species in cured patients, thus suggesting that total elimination of organisms is not necessary for complete recovery. Likewise, bacteria including micrococci, diphtheroids, and gram-negative organisms were recovered from nail-folds throughout the treatment period proving the multifactorial origin of the condition. Daniel et al. assessed the efficacy of ciclopirox 0.77% topical suspension in combination with a strict irritant-avoidance regimen in patients with simple chronic paronychia and/or onycholysis and showed excellent therapeutic outcomes.[16]

Though anti-fungals were the mainstay of therapy in the past, some investigators have suggested that the therapeutic potential of anti-fungals in chronic paronychia might be attributed equally to the anti-fungal and to the anti-inflammatory properties of these agents.[1] Even in studies showing a good therapeutic effect, some of the patients reported unsuccessful anti-fungal therapy in the past.[17] Thus, the accumulating evidence indicates that chronic paronychia is an eczematous condition as discussed above.[18,19] For this reason, topical and systemic steroids have become the first line of therapy, whereas topical and systemic anti-fungals are of little value now, being used only when there is an associated fungal infection.

Tosti et al.[7] conducted a randomized, double-blind study to compare the efficacy of systemic anti-fungals (itraconazole 200 mg daily or terbinafine 250 mg daily) versus a topical corticosteroid (methylprednisolone aceponate cream 0.1%, 5 mg daily) in the treatment of 45 adult patients with chronic paronychia over 3 weeks. The follow-up period was of 6 weeks. The statistical analysis showed a significant difference between the number of nails improved or cured by methylprednisolone aceponate (41 out of 48) and that of nails improved or cured with terbinafine (30 out of 57) or itraconazole (29 out of 64). Presence of Candida was not strictly linked to disease activity, and Candida eradication was associated with clinical cure in only 2 of the 18 patients who carried Candida.

Tacrolimus has been used successfully in treatment of atopic and allergic contact dermatitis. Based on this fact and that irritants and allergens play a pivotal role of in the development of chronic paronychia, Rigopoulos et al.[8] conducted a randomized, unblinded, comparative study to compare the efficacy of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% vs. betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% vs. emollient application for 3 weeks in the treatment of 45 patients with chronic paronychia. Both betamethasone and tacrolimus groups presented statistically significantly greater cure or improvement rates when compared with the emollient group, and tacrolimus ointment appeared to be a more efficacious than betamethasone 17-valerate or placebo for the treatment of chronic paronychia. Possible effect of tacrolimus was explained by its role in the elicitation phase of allergic contact dermatitis through inhibition of dendritic cell migration into the draining lymph node[20] and suppression of both irritant and contact patch test reactions.[21] In addition, the ointment formulation of the tacrolimus might offer increased benefit on the impaired barrier function of the inflammatory perionychium.

Surgical management of chronic paronychia

Surgical management is only indicated in recalcitrant cases of chronic paronychia, which does not respond to medical management and proper use of general measures. Surgical treatment is required in such cases to remove the chronically inflamed tissue, which aids in effective penetration of topical as well as oral medications and regeneration of the cuticle.

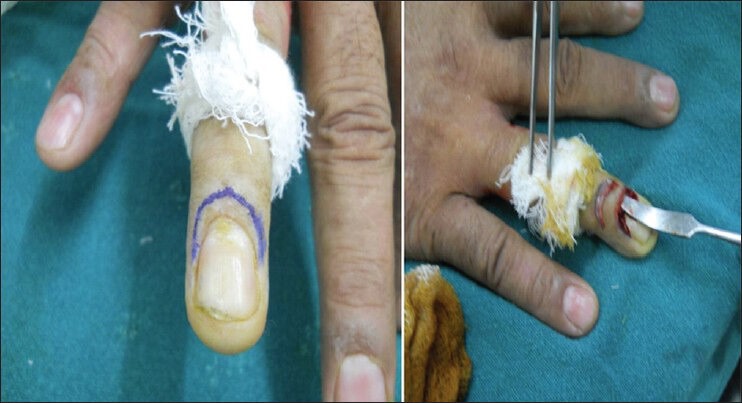

Various surgical techniques with modifications have been described in literature. Keyser et al.[22] in 1975 suggested simple eponychial marsupialization as the treatment of chronic paronychia. In this technique, after anesthesia and tourniquet control, a crescent-shaped incision parallel and proximal to the distal edge of eponychium and extending from the radial to ulnar borders was made [Figure 3]. The width of the crescent was 3 mm from proximal to distal edge. All affected tissue within the boundaries of the crescent and extending down to, but not including, the germinal matrix is excised and packed with gauze pieces. Thus, this procedure exteriorizes the infected and obstructed nail matrix and allows its drainage. Epithelialization of the excised defect occurs over the next 2-3 weeks.

Figure 3.

Eponychial marsupilization in a case of chronic paronychia

Bednar et al.[4] in 1991 treated 7/28 fingers with marsupialization alone and found recurrences in two of these patients who had nail plate irregularities. The 16 patients with nail irregularities were treated with marsupialization plus nail removal, and there were no recurrences with statistically significant difference. The two patients treated with marsupilization alone who showed recurrence were retreated with marsupialization and nail removal and both improved significantly. Thus, they further confirmed that eponychial marsupialization is an effective means of treating chronic paronychia and suggested that nail removal should also be done when concurrent nail irregularities are seen as eponychial marsupialization only drains the dorsal surface of the dorsal roof of germinal matrix, whereas nail removal more thoroughly debrides the entire nail fold by permitting drainage of the volar portion of the dorsal roof as well as the ventral floor.

Eponychial marsupilization preserves the ventral surface of the PNF, which forms the dorsal roof or surface of the nail plate, thus the authors claimed that it produces a cosmetically more acceptable result as compared to en bloc excision of PNF (complete removal of the dorsal roof including the eponychium), since it prevents any subsequent roughness or lack of shininess over the nail plate surface.

Baran et al.[23] Suggested en bloc excision of proximal nail fold as a treatment option for chronic paronychia based on their observation that sites of biopsies from proximal nail fold in cases of collagen disorders healed uneventfully without scarring or distortion in about three weeks. In this procedure, they excised a crescent-shaped piece of full thickness skin, 5-6 mm wide at greatest diameter that extends from one lateral nail fold to the opposite one and includes the entire proximal nail fold [Figure 4]. Complete healing and restoration occurred in three months. They postulated that this method was simpler, curative, and cosmetically and functionally more satisfactory than eponychial marsupialization.

Figure 4.

En bloc excision of the proximal nail fold in a case of chronic pronychia

Grover et al.[24] treated 30 patients of chronic paronychia with nail plate irregularities by en bloc excision of PNF with or without nail plate removal. Of these, 70% of patients were cured in group, in which en bloc excision with nail avulsion was performed, whereas only 41% were cured in group where en bloc excision without nail avulsion was performed; however, the difference was not significant statistically. Thus, they concluded that though en bloc excision of the PNF is a useful method in recalcitrant paronychia, simultaneous nail avulsion improves the surgical outcome.

The authors also claimed that a fibrosed, avascular distal eponychium would not contribute effectively towards a normal nail plate surface or produce a new cuticle as postulated by supporters of eponychial marsupilization, and thus preserving the eponychium does not offer any added advantage. Moreover, all these patients of en bloc excision of PNF showed an effective regeneration of eponychium and cuticle with normal attachment to nail plate and no loss of post-op shininess.

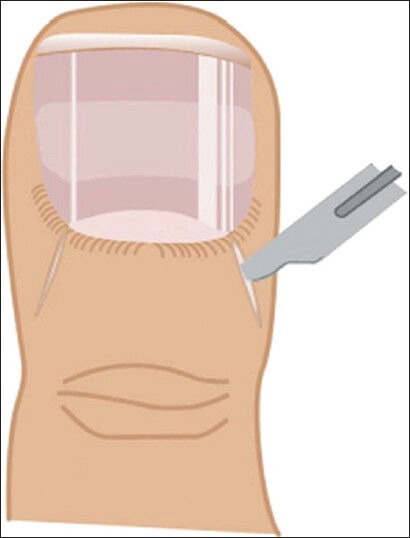

Recently, Pabari et al.[25] described Swiss roll technique for chronic and severe acute paronychia with run around infection involving both nail folds. In this technique, the nail fold is elevated by making an incision on either side using a no. 15 scalpel blade with the scalpel tip pointed away from the nail bed to prevent iatrogenic deformity of the nail [Figure 5]. The elevated nail fold is reflected proximally over a non-adherent dressing [Figure 6] that is rolled up like a Swiss roll and secured to the skin with 2 anchoring non-absorbable sutures. The exposure of the nail bed allows drainage of any residual infection. The finger is subsequently dressed with a simple finger dressing. If the wound is clean at 48 hours, the anchoring sutures are removed, and the nail fold is allowed to fall back to its original position and heal by secondary intention. In chronic paronychia, the fold may be kept open for up to 7 days to allow adequate drainage. This technique has the advantage of retaining the nail plate and allowing rapid healing without creating a defect in the skin.

Figure 5.

Swiss roll technique: Incision made on either side of nail fold for nail fold elevation (adapted from Pabari A, Iyer S, Khoo CT. Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Surg 2011;15:75-7)

Figure 6.

Swiss roll technique: Elevated nail fold is reflected proximally over a non-adherent dressing (adapted from Pabari A, Iyer S, Khoo CT. Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Surg 2011;15:75-7)

Prognosis

Chronic paronychia responds slowly to treatment and may take several weeks or months, but this should not be a deterrent to therapy. If the patient is not treated, sporadic painful episodes of acute inflammation may be experienced as a result of continuous penetration of various pathogens.

Conclusion

Thus, chronic paronychia should no longer be considered a mycotic disease but an eczematous condition with multifactorial etiology. Preventive measures should always form the main part of therapy. Topical steroids have a major role to play in therapy and are more effective than systemic anti-fungals (level of evidence B). Tacrolimus has recently shown to have promising results. Surgical therapy should be resorted to in recalcitrant cases, and simultaneous nail removal augments the results in most cases.

What is new?

Chronic paronychia has a multifactorial etiology and is primarily a form of hand dermatitis and not fungal infection. Steroids have a definite edge over anti-fungals in the management of chronic paronychia. Tacrolimus has recently shown to have promising results. The surgical methods used for recalcitrant cases give better results when the nail plate is also removed simultaneously. A new surgical technique namely Swiss roll technique has been described, which has the advantage of retaining the nail plate and allowing rapid healing without creating a defect in the skin.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rockwell GP. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleckman P. Structure and function of the nail unit. In: Scher RK, Daniel CR III, editors. Nails: Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover C, Reddy BSN, Chaturvedi KU. Nail biopsy, an assessment of indications and outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:190–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bednar MS, Lane LB. Eponychial marsupialization and nail removal for surgical treatment of chronic paronychia. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16:314–7. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A color guide to diagnosis and therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby; 2004. Nail diseases; pp. 871–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay RJ, Baran R, Morre MK, Wilkinson JD. Candida onychomycosis – an evaluation of the role of Candida species in nail disease. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Ghetti E, Colombo MD. Topical steroids versus systemic antifungal in the treatment of chronic paronychia: An open, randomized double-blind and double dummy study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:73–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Belyayeva E, Larios G, Kontochristopoulos G, Katsambas A. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% vs. betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% in the treatment of chronic paronychia: An unblinded randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:858–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tosti A, Guerra L, Morelli R, Bardazzi F, Fanti PA. Role of foods in the pathogenesis of chronic paronychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:706–9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosti A, Pirracini B, Antuono AD. Paronychia associated with antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1165–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roe E, Garcia MP, Marcuello E. Description and management of cutaneous side effects during cetuximab or erlotinib treatments: A prospective study of 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:429–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, Alevizos A. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:339–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samman PD. Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1979. pp. 1834–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow AJ, Chattaway FW, Holgate MC, Aldersley T. Chronic paronychia. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:448–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1970.tb02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong ES, Hay RJ, Clayton YM, Noble WC. Comparison of the therapeutic effect of ketoconazole tablets and econazole lotion in the treatment of chronic paronychia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:489–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1984.tb00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniel CR, Daniel MP, Daniel J, Sullivan S, Bell FE. Managing simple chronic paronychia and onycholysis with ciclopirox 0.77% and an irritant-avoidance regimen. Cutis. 2004;73:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amichai B, Shiri J. Fluconazole 50 mg⁄day therapy in the management of chronic paronychia. J Dermatolog Treat. 1999;10:199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Paronychia. In: Amin S, Lahti A, Maibach HI, editors. Contact urticaria syndrome. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1997. pp. 267–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaias N. Paronychia. In: Zaias N, editor. The nail in health and disease. 2nd ed. Norwalk (CT): Appleton and Lange; 1990. pp. 131–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumer W, Sülzle B, Weigt H. Cilomilast, tacrolimus and rapamycin modulate dendritic cell function in the elicitation phase of allergic contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:136–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauerma AI, Stein BD, Homey B. Topical FK 506: Suppression of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in the guinea pig. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:337–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00402225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keyser JJ, Eaton RG. Surgical cure of chronic paronychia by eponychial marsupialization. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:66–70. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baran R, Bureau H. Surgical treatment of recalcitrant chronic paronychia of the fingers. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:106–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grover C, Bansal S, Nanda S. En bloc excision of proximal nail fold for treatment of chronic paronychia. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:393–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pabari A, Iyer S, Khoo CT. Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Surg. 2011;15:75–7. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181ec089e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]