Abstract

Background:

Acquired, non-nevoid, apparently idiopathic facial pigmentation are distributed over some specific locations like periorbital area, zygomatic area, malar area, root of nose, perioral and mandibular area. Periorbital pigmentation is the most well known entity in this group. These are bilaterally distributed homogenously diffuse gray to dark gray or slate-gray colored patches showing progressive intensification of pigmentation. These are often considered as physiologic or constitutional pigmentation. Some portions of the margins of these patches were described previously as pigmentary demarcation line (PDL- F, G, H).

Aim:

To analyze the distributional patterns of acquired, apparently idiopathic facial pigmentations and to evaluate the etiologic aspects of these conditions.

Materials and Methods:

Spatial patterns, distribution, and orientation were analyzed among 187 individuals with idiopathic non-nevoid, facial pigmentation. Observed patterns were compared with various pigmentary nevi and Blaschko's lines on face.

Results:

It was found that most of the idiopathic facial pigmentary alterations including periorbital pigmentation and PDL on face had specific patterned distribution that had high similarity to that of the pigmentary nevi and Blaschko's lines on face.

Conclusion:

It is hypothesized here that phenotypic expression of acquired patterned pigmentation (AIFPFP) is due to genetically determined increased pigmentary functional activity to various known and unknown yet natural factors like UV rays and aging. Mosaicism was a definite possibility. We also consider that the patterns actually reflected the normal patterns of embryological human pigmentation on face.

Keywords: AIPFP, facial pigmentation, lines of Blaschko, mosaicism, periorbital pigmentation, pigmentary demarcation line, PDL, zygomatic pigmentation

Introduction

What was known?

Acquired, idiopathic, patterned facial pigmentations are known to be physiological or constitutional. There has been no definite evidence that these pigmentations including periorbital pigmentation and PDL on face are distributed along the Blaschko's lines.

Facial pigmentation may develop in a wide range of known and unknown conditions. Melasma, nevi, macular amyloidosis,[1] erythema dyschromicum perstans,[2] photosensitive diseases, pigmented contact dermatitis, drugs, seborrheic melanosis, actinic lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus are known to induce facial pigmentation. Atopic dermatitis is also known to develop pigmentation around eye.

Apart from these conditions, a large number of individuals develop acquired, idiopathic, non-nevoid, facial pigmentations that are frequently distributed in a patterned manner over preferential locations. Periorbital pigmentation is the most well known entity in this group. This is particularly common among many black races including India.[3,4,5] Different conditions like fatigue, anxiety, dehydration excessive sun exposure, drugs, hormonal causes, pregnancy and breast-feeding have been mentioned as the possible precipitating and aggravating factors for such pigmentation. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, shadow effects due to an overhanging tarsal muscles, eye-bags, or a deep tear trough have also been referred to as possible cause of periorbital pigmentation.[6,7] This was often referred to as constitutional, idiopathic,[6,7,8,9] familial and genetic.[10] Apart from periorbital pigmentation, existence of other types of idiopathic patterned pigmentation on face has been mostly ignored so far, although, some of these are also commonly seen.

Common to all these highly prevalent pigmentations are their apparently idiopathic nature, acquired onset, bilateral distribution, progressive intensity and homogenously diffuse gray to dark gray or slate-gray color. No well-accepted consensus seems to exist regarding their status as a disease.

The present study is done to analyze the distributional patterns of acquired, apparently idiopathic facial pigmentations. These were compared with various pigmentary nevi (both hypo and hyper) and the Blaschko's line of face[11] and also with the recently described specific Blaschko's lines for pigmentary nevi.[12] to elucidate some possible genetic mechanism for these conditions.

Materials and Methods

Two hundred and fifty consecutive cases of apparently idiopathic facial pigmentation belonging to all ethnic populations and religions, any ages, and both sexes were selected from the outpatient department in a tertiary care hospital during one-year period. The criterion for selection was apparently idiopathic, asymptomatic, acquired and non-nevoid condition without any form of surface changes other than hyperpigmentation. Thus we excluded all cases with pigmentation from other clinically identifiable or suspected etiologies like nevi, melasma, seborrheic melanosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, photosensitive diseases, pigmented allergic contact dermatitis and macular amyloidosis. Associated surface alterations like thickening, atrophy, telengiectasia, presence or history of persistent eye itching (or on other patches), post-inflammatory hyper-pigmentation and history of chronic exposure to drugs that could induce pigmentation were also excluded.

On further examination, few cases were excluded who might have overlapping melasma, cases who had extensive macular amyloidosis, extensively present elsewhere in the body and few individuals who were unwilling to take part in the study.

They were enquired about the family history, age and mode of onset, nature of progression, suspected aggravating factors and presence of any symptom associated with the pigmentation.

The shape, orientation and pattern of these pigmented patches and their margins were compared with the pigmentary nevi on face (hypo and hyperpigmented), Blaschko's line of face.

Consent was taken from the participants before inclusion into the study and before taking photographs as well. The study was approved by institutional ethical committee.

Results

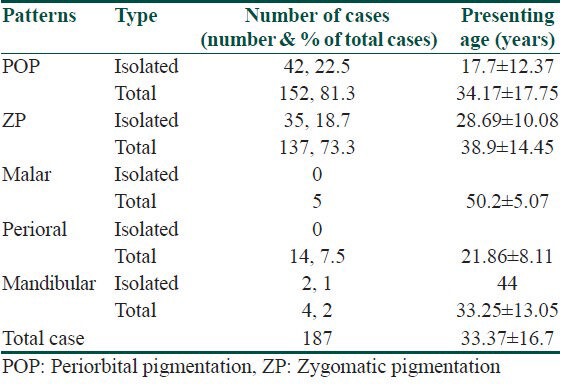

Total cases included were 187. Mean age at presentation was 33.37 ± 16.7 years. Mean age of presentation of isolated periorbital pigmentation (17.7 ± 12.37 years) and perioral pigmentation (21.86 ± 8.11 years) was significantly less than the total average (33.37 ± 16.7) (P = 0.0235 and 0.001, respectively). Male to female ratio was 1:1.37. History of definite familial occurrence (same or other patterns of idiopathic pigmentation) was mostly unavailable except for perioral involvement that was reported to be common in families (36% positive family history) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Different patterns of pigmentation

Color of all the pigmented patches under discussion was diffuse, light to dark gray, or slate-gray. Erythematosus hue was prominent in some fairer young individuals. Margins were generally detectable with some parts being distinctly sharp. Distribution, shape, and orientation pattern also varied but maintained a regular and expected uniform pattern. Gradually progressive darkening was mentioned by almost all cases. Some areas developed relatively higher intensity than the other areas. Some parts of the patch were often not completely discernible, at least initially. The patterns of pigmentation were anatomically categorized as periorbital, zygomatic, malar, perioral, upper nasal, and mandibular pigmentation.

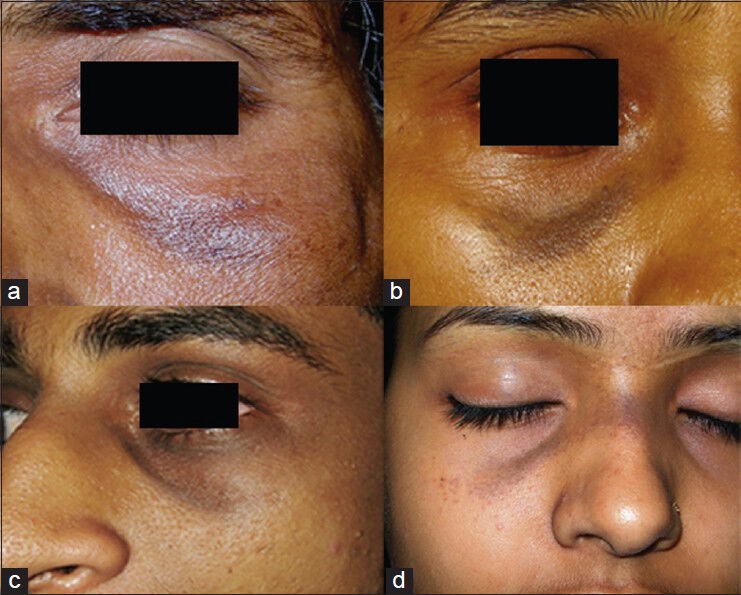

Periorbital pigmentation was the most common pattern observed (81.3%). This and perioral pigmentation were found to start earlier than others. One male child of 1.2 years had periorbital pigmentation of the medial infraorbital region [Figure 1]. The child had her mother affected with more intense periorbital pigmentation.

Figure 1.

A child aged 1 year 2 months having infraorbital pigmentation with erythematosus hue over the medial half

Pigmentation was commonly noted over both supra and infraorbital area but upper eye lid pigmentation was slightly more common than lower eye lid area. Higher intensity of pigmentation was noted at some areas like most medial part of both supraorbital and infraorbital areas and sometimes the medial part of the infraorbital rim. Generally, the upper eyelid formed the supraorbital part of periorbital pigmentation but in more advance cases, pigmentation extended higher but a distinct area of sparing beneath the eyebrow was almost always noted [Figure 2c and d].

Figure 2.

Different patterns of periorbital pigmentation. (a and b) Medially, extension over root of nose and laterally continuation as zygomatic pigmentation. (c) Most medial part of supraorbital area showing most intense pigmentation. (d) Periorbital pigmentation without any zygomatic pigmentation. (e and f) Blaschko's lines on face for pigmentary nevi (Figure 2e shows the simplified version of original figure for easier comparison)

Infraorbital part was generally margined in the lower part by the bony orbital rim. Sometimes it was found to extend over the cheek [Figure 2a]. Medial infraorbital area often showed earlier onset and more intense pigmentation than lateral area. Darker pigmentation was also noted over the infraorbital rim than the rest part [Figures 2 and 3]. Some occasional cases had prominent pigmentation only over the medial infraorbital rim [Figure 3]. Pigmentation was noted more laterally as a separate curved patch that started from the margin of eyelid and extended laterally to continue as the zygomatic patch. Thus, frequently there existed a curved area of sparing in the infraorbital area [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 3.

(a) Pigmentation exclusively over infraorbital rim. (b) Nevus of Ota with similar pattern. (c) Pigmentation in the infraorbital area with area of sparing and extension over root of nose. (d) Nevus of Ota with similar pattern of distribution

Periorbital pigmentation was often found to extend medially over the root of the nose [Figures 3 and 4]. Often it merged with the opposite side. It was observed only among the middle-aged people, who also had prominent periorbital pigmentation. Intensity of the pigmentation on the sides of nose was higher than the anterior surface of nose as well as the periorbital pigmentation. Apparently, it appeared as the medial extension of the periorbital pigmentation.

Figure 4.

Different patterns of zygomatic pigmentation (a, b, d, and f) and pigmentary nevi with similar patterns (c and f). Patterns have been compared with Blaschko's lines (simplified) on face for pigmentary nevi (g and f). (Figure 4c and 4f have been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Second common pattern was pigmentation lateral to eyes on the zygomatic area that has been mentioned as zygomatic pigmentation (73.3%). It was found to be oriented laterally and downwards with an outward curve [Figure 4]. At the upper and medial end, it almost, always started at the lateral part of eye as the continuation of pigmentation of this part of periorbital pigmentation. However, among many individuals, at the initial stage of development of pigmentation, the area near eye was the most indistinct part. In many other cases with prominent zygomatic pigmentation, this medial end was broad and merged with the lateral end of upper eye pigmentation. Zygomatic pigmentation extended laterally on lateral part of cheek over the zygomatic bone, generally lateral to zygomatic eminence.

Size of the zygomatic pigmentation varied with some very small and other having large and complete shape [Figure 5]. Lower lateral margin of zygomatic pigmentation formed a blunt or angulated end. Not uncommonly, this lower part had more than one ends [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

(a) A small zygomatic pigmentation. (b) Similar pattern of depigmented nevus. (c) Blaschko's line (simplified) on face for pigmentary nevi. (Figure 5b has been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Figure 6.

Left panel (a and b) shows inferolateral end of zygomatic pigmentation having multiple angulated projections. (c) A depigmented nevus of similar pattern. (d) Blaschko's line (simplified) on face for pigmentary nevi. (Figure 6c has been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Rarely, pigmentation was noted to be distributed on more medial aspects of cheek or the malar area [Figure 7]. This happened in different forms. In some cases, zygomatic pigmentation appeared wider and its medial margin encroached over the cheek. In others, a completely separate patch that started more medially at infraorbital area than classical zygomatic pigmentation extended over cheek. No case of isolated malar patch was observed. There existed a distinct spared area in between the malar patch and typical zygomatic pigmentation

Figure 7.

Upper panel (a and b) shows pigmentation on cheek. (a) Zygomatic pigmentation extended medially over cheek. (b) A separate patch appeared on cheek with a distinct spared area in between two patches. (c) Pigmentary nevus involving periorbital area and cheek. (d) Blaschko's line on face for pigmentary nevi (simplified). (Figure 7c has been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Perioral pigmentation was noted in 14 cases. There were high number (>35%) of familial occurrence with this type. Most cases were also associated with periorbital pigmentation. Pigmentation involved the area above upper lips and the chin. Laterally it was approximately limited by the nasolabial folds and mentolabial folds. Thus, these pigmented patch was found to be oriented downward and laterally. It spared the lips and the mentum or the chin bulge appeared distinctly less involved [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Upper panel shows perioral pigmentation. Lower panel shows different nevi at similar areas. (8 D, E, F has been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Four individuals had pigmentation over the mandibular area. This pigmentation stretched from sides of cheek in front of ear and advanced in a downward curved fashion till the perioral areas [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

(a and b) Curved mandibular pigmentation. (c) Nevus depigmentaosus and (d) Blaschko's lines on face for pigmentary nevi. (Figure 9d has been reproduced with permission from Ref 12)

Other important observation was presence of freckles predominantly over many of these patterned patches [Figures 2a, 5a and e, 7a, 8b, 9c].

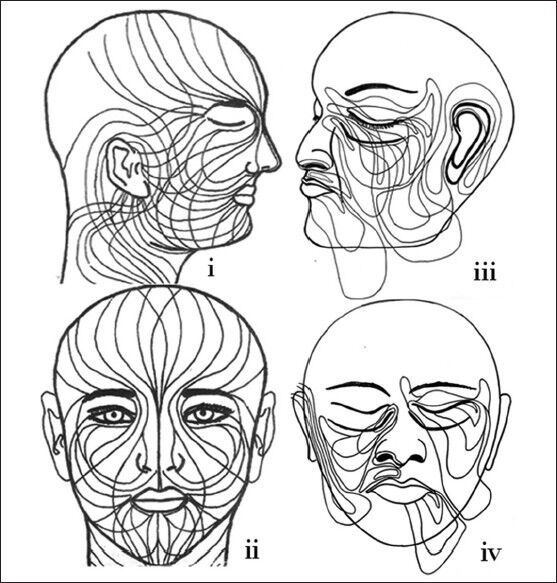

There was high degree of similarity in the shape, orientation, and pattern of these idiopathic pigmented patches with the same of many pigmentary nevi, Blaschko's line of face and with the recently described specific Blaschko's lines for pigmentary nevi as well [Figure 10]. For easier comparison, a simplified form of the latter that had fewer lines on the periorbital area was used as shown in many of the previous figures.

Figure 10.

Blaschko's lines on face on left panel (i, ii) and Blaschko's lines on face for pigmentary nevi (iii, iv) (This figure has been reproduced with permission from Ref 11 and Ref 12)

Discussion

Periorbital pigmentation was described by some authors to be inherited in autosomal dominant manner.[3,10,13] Although, some familial cases have been examined, familial pattern of these conditions could not be evaluated in this hospital-based study.

Most of the individuals could not recollect the correct age of onset. A case of periorbital pigmentation presenting at 1.2 years was probably the youngest one to be reported with periorbital pigmentation.

Most of the observed idiopathic pigmentation on face was found to be patterned, bilateral, having a homogenous, gray, dark gray or rarely slate-gray color indicating a deeper level of the pigment.

With their typical presentation, identification and differentiation from other common pigmentations on face was generally not difficult unless they had atypical manifestations or had overlap. Melasma was differentiated with their brownish tinge, irregular, scalloped margin, and frequent reticular appearance. However, malar patch was found to be commonly overlapped by melasma. It was the reason for very low number of this type of patch being included in this study.

Lower eye pigmentation has been previously mentioned as more common than upper.[7,14] We also have found that the lower eye pigmentations were often the reason for seeking medical advice. However, we noticed that upper eye pigmentation was actually little more common in occurrence. The later was often even more intense as shown in the figures. This was most possibly due to anatomical location of upper eyelid that was less visible while eyes were open. Thus, any hyperpigmentation involving upper eyelid was less distressing.

Progressive increment in the intensity of pigmentation was reported by most. Ultraviolet rays possibly played some definite role in it. Development of pigmentation of higher intensity over some of the more exposed areas like lower part infraorbital area where pigmentation sometimes even extended beyond the rim to reach upper cheek in advanced ages indicated that UV rays had some aggravating role. Development of freckles preferentially on the periorbital and zygomatic patch were considered indirect evidence of not only the possible role of UV rays in accentuation of pigmentation but also the higher functional activity of the melanocytes of these patches.

Some of the patterned pigmentation like that on periorbital and perioral areas is known to have slightly higher pigmentation since early age in large number of population. Thus, pigmentation of these areas often has been referred to as constitutional or physiological. We also believe that these patches are genetically determined and physiological factors play the leading role in accentuation of the pigmentation. More intense pigmentation within a patterned patch (e.g. zygomatic pigmentation) than the similarly exposed surrounding area can only be explained by the genetically determined higher functional activity within these patches.

Due to the unusual similarity in the spatial patterns of these patches with many pigmentary nevi and Blaschko's lines, mosaicism due to some early post-zygotic genetic aberration involving the precursor melanoblast could be a possible explanation. However, it seems somewhat confusing as there have been no previously described apparently physiological conditions to follow Blaschko's lines or other patterns of mosaicism. It is very difficult to accept that large number of population is affected by genetic mosaicism that leads to almost similar type of phenotypic expression. Our findings also have nothing to propose their status as a disease. So, we simply suggest that these are genetically determined, predefined patches with higher functional capacity than surrounding areas to wide arrays of factors like UV rays, aging and many unidentified factors. Mosaicism remains a strong possibility for their altered functional activity and pattern. This can be confirmed only after cytogenetic analysis.

Patterns of embryological pigmentation on human face have recently been proposed.[12] Pigmentary nevi that develop due to genetic aberration, known as genetic mosaicism involving these precursor cells are the only known condition to render the spatial patterns of embryological pigmentary segments visible. Rather than simply representing the migration lines for primitive cells like melanoblast, Blaschko's lines specific for pigmentary nevi have been shown to follow the margins of a pigmentary nevi signifying the pattern and orientation of the nevi.[12] This theory successfully explains the normal human pigmentation pattern more logically and incorporates the post-migration proliferation stage of melanoblast. Thus, an important proposal was that the spatial patterns of a pigmentary nevi like shape, distribution, and orientation exactly represent the same for a pigmentary segment that would have normally been formed from that particular precursor melanoblast, had there been no genetic aberration.[12] This theory explains well the possibility that acquired idiopathic pigmented patches possibly represent the normal human pigmentation pattern in these particular locations.

As mentioned, some of these margins or some parts often appeared as sharp and clearly distinct. For example, the inferomedial margins of the zygomatic patches were found to be often very sharp and distinct. Interestingly, this was observed to conform to what has been previously mentioned as pigmentary demarcation line type F (PDL-F).[15] It was also described that PDL-F extended as periorbital pigmentation.[16] We have also observed that the lateral margins of the perioral pigmentation roughly follow the nasolabial fold in the upper part and the mentolabial fold in the lower part. Possibly, parts of this margin represent what has been previously mentioned as PDL-H pattern.[17]

Matzumoto first described the PDL.[18] A subsequent population survey confirmed its existence.[19] Several types of PDL have been described.[15,17,20] It had been postulated that PDLs are distributed along the cutaneous nerves and the dermatomes.[21,22] Role of hormones[23] and genetics[24] had also been suggested. Before the introduction of any of the facial PDL, Krivo[25] found similarity in the distribution of PDL with the Blaschko's lines that was proposed by Bolognia et al.[26] However, it was not accepted by others due to lack of significant evidence.[27] From the analytical evaluation of all these lines on face, we have provided evidence, which proposes that all the described PDLs on face including PDL-F, G and H actually represent the margins of such patches and they closely conform with the Blaschko's lines on face. Thus, we propose that mosaicism may play a role in the development of PDL also. Due to the expected variations in the inferior end of zygomatic patch, V or W pattern, appearance that are even more complex is expected. However, as there can be innumerable number of Blaschko's lines, we feel that it may not be logical to describe each of them as a new type of PDL. Describing each of them as Blaschko's line appears more rational.

This is probably the first large study of its kind to evaluate acquired, non-nevoid, idiopathic facial pigmentation. These all may be better grouped under an umbrella term called acquired, idiopathic, patterned facial pigmentation or in short AIPFP.

What is new?

Acquired, idiopathic, patterned facial pigmentation follows the lines of Blaschko and possibly results from mosaicism. Their patterns reflect the embryological pigmentation patterns in human. Periorbital pigmentation and pigmentary demarcation lines (PDL) on face actually represented Blaschko's lines of face.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.van den Berg WH, Starink TM. Macular amyloidosis, presenting as periocular hyperpigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:195–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1983.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ing EB, Buncic JR, Weiser BA, de Nanassy J, Boxall L. Periorbital hyperpigmentation and erythema dyschromicum perstans. Can J Ophthalmol. 1992;27:353–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulk CS. Primary disorders of hyprpigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gellin GA. Dark circles around eye. J Am Med Assoc. 1981;245:1165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimbow M, Jimbow K. Pigmentary disorders in oriental skin. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:11–27. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(89)90053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh MR, Chung KY. Infraorbital dark circles: Definition, causes, and treatment options. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1163–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranu H, Thang S, Goh BK, Burger A, Goh CL. Periorbital hyperpigmentation in Asians: An epidemiologic study and a proposed classification. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia A, Fulton JE., Jr The combination of glycolic acid and hydroquinone or kojic acid for the treatment of melasma and related conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:443–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duke-Elder S. The eyelids. The ocular adnexae. In: Duke-Elder S, editor. Text of Ophtalmology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1952. pp. 364–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman RM, Belcher RW. Periorbital hyperpigmentation. An overlooked genetic disorder of pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:169–74. doi: 10.1001/archderm.100.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Happle R, Assim A. The lines of Blaschko on the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:612–5. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarma N. Pigmentary nevi on face have unique patterns and implications: The concept of Blaschko's lines for pigmentary nevi. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:30–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.92673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters R. Auffallende dunkelfarburg der unteren Lider als erbliche Anomaliie. Zbl Prakt Augenheilk. 1918;42:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe NJ, Wieder JM, Shorr N, Boxrud C, Saucer D, Chalet M. Infraorbital pigmented skin. Preliminary observations of laser therapy. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:767–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malakar S, Dhar S. Pigmentary demarcation lines over the face. Dermatology. 2000;200:85–6. doi: 10.1159/000018330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malakar S, Lahiri K, Banerjee U, Mondal S, Sarangi S. Periorbital melanosis is an extension of pigmentary demarcation line-F on face. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:323–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.34009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somani VK, Razvi F, Sita VN. Pigmentary demarcation lines over the face. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:336–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matzumoto SH. Uber aine eigentumliche Pigmentverteilung an den Voigetschen Linien. Arch Dermatol Syphil. 1913;118:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.James WD, Carter JM, Rodman OG. Pigmentary demarcation lines: A population survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:584–90. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selmanowitz VJ, Krivo JM. Pigmentary demarcation lines. Comparison of Negroes with Japanese. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:371–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb06510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maleville J, Taïeb A. Pigmentary demarcation lines as markers of neural development. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1459. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890470139025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dupré A, Maleville J, Lassère J, Aillos O. [Axial dermatoses (author's transl)] Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1977;104:304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vazquez M, Ibanez MI, Sanchez JL. Pigmentary demarcation line during pregnancy. Cutis. 1986;38:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selmanowitz VJ, Krivo JM. Hypopigmented markings in Negroes. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:229–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1973.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krivo JM. How common is pigmentary mosaicism? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:527–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:157–90. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlow SJ. How common is pigmentary mosaicism.? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]