Abstract

Demodex mite is an obligate human ecto-parasite found in or near the pilo-sebaceous units. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are two species typically found on humans. Demodex infestation usually remains asymptomatic and may have a pathogenic role only when present in high densities and also because of immune imbalance. All cutaneous diseases caused by Demodex mites are clubbed under the term demodicosis or demodicidosis, which can be an etiological factor of or resemble a variety of dermatoses. Therefore, a high index of clinical suspicion about the etiological role of Demodex in various dermatoses can help in early diagnosis and appropriate, timely, and cost effective management.

Keywords: Demodex, demodicosis, demodicidosis, ecto-parasite

Introduction

What was known?

Demodex mite infestation usually remains asymptomatic, but may be an important causative agent for many dermatological conditions.

Demodex, a genus of tiny parasitic mites that live in or near hair follicles of mammals, are among the smallest of arthropods with two species Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis typically found on humans. Infestation with Demodex is common; prevalence in healthy adults varying between 23-100%.[1,2] Demodex infestation usually remains asymptomatic, although occasionally some skin diseases can be caused by imbalance in the immune mechanism. In this article, we have described the mite and have highlighted its dermatological importance.

General considerations of Demodex

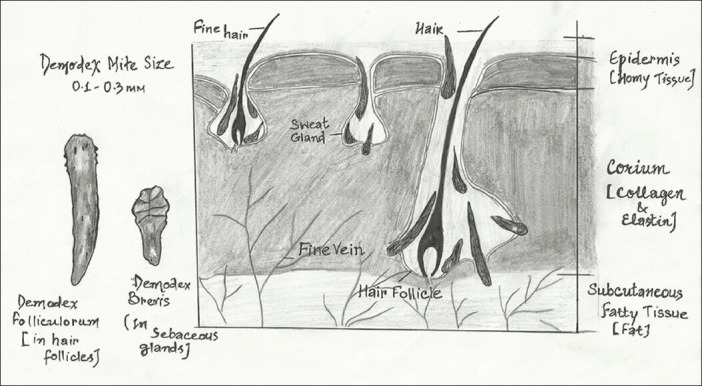

Demodex mite is an obligatory human ecto-parasite, and it is resident in or near the pilo-sebaceous units.[3] About 65 species of Demodex are known. Two species D. folliculorum and Demodex brevis, collectively referred to as Demodex, are typically found on humans, occurring in 10% of skin biopsies and 12% of follicles[4,5] [Figure 1]. Identification of these mites dates back to 1841-42 for D. folliculorum by Simon and 1963 for D. brevis by Akbulatova.[4,6,7]

Figure 1.

Demodex mite, an obligatory human ecto-parasite resides in or near the pilo-sebaceous units

Species/genus identification

Demodex is a saprophytic mite that belongs to family Demodicidae, class Arachnida, and order Acarina.[8]

Morphology

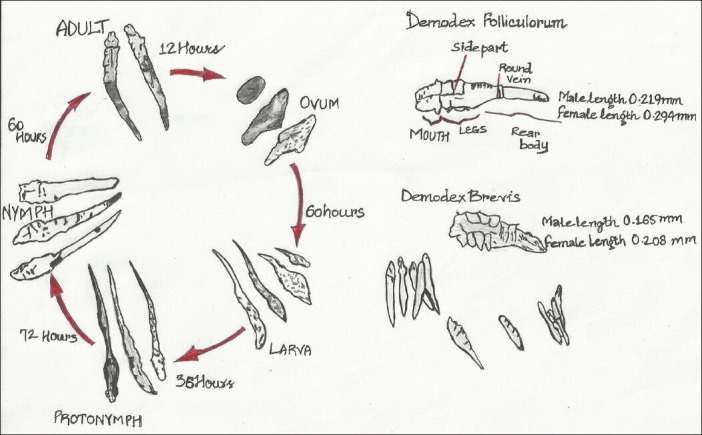

Adult D. folliculorum mites are 0.3-0.4 mm in length and that of D. brevis are slightly shorter of 0.15-0.2 mm length,[2] with females somewhat shorter and rounder than males [Figure 2]. This makes them invisible to the naked eye, but, under the microscope, their structure is clearly visible. It has a semi-transparent, elongated body that consists of two fused segments. Eight short, segmented legs are attached to the first body segment. The eight legs of this mite move at a rate of 8-16 mm/h and this is mainly done during the night as bright light causes the mite to recede into its follicle. The body is covered with scales for anchoring itself in the hair follicle and the mite has pin-like mouth parts for eating skin cells, hormones, and oils (sebum) accumulating in the hair follicles.[2,4,5]

Figure 2.

Morphology and life cycle of the Demodex mite

Sites of involvement

Demodex is an ecto-parasite of pilo-sebaceous follicle and sebaceous gland, typically found on the face including cheeks, nose, chin, forehead, temples, eye lashes, brows, and also on the balding scalp, neck, ears.[4,5] Other seborrheic regions such as naso-labial folds, peri-orbital areas, and less commonly upper and medial region of chest and back are also infested.[2] They may also be found on penis, mons veneris, buttocks, and in the ectopic sebaceous glands in the buccal mucosa.[2]

D. folliculorum is more commonly localized to the face, while D. brevis is more commonly found on the neck and chest.[9] Infestation with D. folliculorum is more common than with D. brevis, but the later has wider distribution on the body.[4] D. folliculorum is usually found in the upper canal of the pilo-sebaceous unit at a density of ≤ 5/sq cm[4] and uses skin cells and sebum for nourishment.[3,10] Several mites, with heads directed toward the fundus, usually occupy a single follicle.[4,11] D. brevis, on the other hand, burrows deeper into the sebaceous glands and ducts and feeds on gland cells.[5] Penetration of Demodex into the dermis or, more commonly, an increase in the number of mites in the pilo-sebaceous unit of > 5/sq cm,[4] is believed to cause infestation, which triggers inflammation.[10,12] Some authors consider the density of > 5 mites per follicle as a pathogenic criterion.[10,13]

Life cycle

Female Demodex are somewhat shorter and rounder than males. Both male and female Demodex mites have a genital opening and fertilization is internal. Mating takes place in the follicle opening and eggs are laid inside the hair follicles or sebaceous glands. The six-legged larvae hatch after 3-4 days, and the larvae develop into adults in about 7 days. It has a 14-day life cycle[6] [Figure 2]. The total lifespan of a Demodex mite is several weeks. The dead mites decompose inside the hair follicles or sebaceous glands.

Age/sex consideration of infestation

The number of Demodex mites present in the lesion increases with age.[9] The prevalence of infestation with Demodex mites is highest in the 20-30 years age group, when the sebum secretion rate is at its highest.[14] Older people are also more likely to carry the mites.[15] Demodicosis is exceptionally seen in children aged <5 years.[16,17] Presumably, Demodex passes to newborns through close physical contact after birth; however, due to low sebum production, infants and children lack significant Demodex colonization.[5]

Infestation of both species is more common in males than in females, with males more heavily colonizing than females (23% vs 13%) and harboring more D. brevis than females (23% vs 9%).[4]

Mode of transmission

The mites are transferred between hosts through contact of hair, eyebrows, and sebaceous glands on the nose.

Methods of detection on body

Demodex is not easily detected in histological preparations; therefore, skin surface biopsy (SSB) technique with cyanoacrylic adhesion is a commonly used method to measure the density of Demodex.[10] It allows the collection of the superficial part of the horny layer and the contents of the pilo-sebaceous follicle;[18] however, it can fail to collect the complete biotope of D. folliculorum.[12] Other sampling methods used in assessing the presence of Demodex by microscopy include adhesive bands, skin scrapings, skin impressions, expressed follicular contents, comedone extraction, hair epilation, and punch biopsies.[11,19] The resulting number of mites measured varies greatly depending on the method used.[11] With modern, and more sensitive, assays, the prevalence of Demodex in skin samples approaches 100%; therefore, mere presence of Demodex does not indicate pathogenesis. Rather, more important in diagnosing Demodex pathology is the density of mites or their extra-follicular location.[19]

Predisposing factors

Most people are only carriers of Demodex mites and do not develop clinical symptoms. Human demodicosis can therefore be considered as a multi-factorial disease, influenced by external and/or internal factors.[20]

One of the factors for the transition from a clinically unapparent colonization of mites to dermatoses can be the development of primary or secondary immunodepression.[20,21] Primary immune suppression is most probably based on hereditary defect of T cells, subsequently reinforced by substances that are produced by mites and by bacteria, with intact B cell immunity.[20,22,23] The fact that people and animals with immunodeficiency are prone to infestation with Demodex mites has been shown repeatedly.[24,25]

Secondary immune suppression predisposing to demodicosis follows corticosteroid, cytostatic therapy, or due to diseases of an immune-compromised nature such as malignant neoplasia, hepatopathies, lymphosarcoma, and HIV infection.[25,26,27,28] There may, however, be factors other than generalized immunosuppression leading to the development of demodicosis.[29] It has been suggested that infestation may be related to genetic predisposition[30] and also with special types of HLA, although some HLA types are considered to be resistant to demodicosis.[29]

Immunopathogenesis

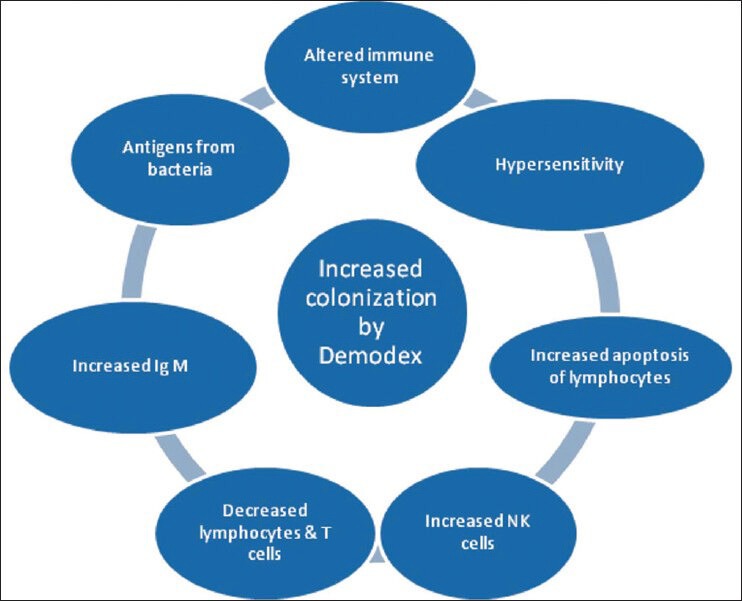

Pathogenesis of demodicosis and immune response to mite invasion are poorly understood.[31,32] Many views have been put forth [Figure 3] as follows:

Figure 3.

Factors involved in pathogenesis

Altered immune system, especially in immune-deficient individuals, which eventually causes a skin disorder.

Hypersensitivity against the mite itself; the evidence being that histopathological examination reveals a dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and typical granulomas predominantly composed of CD4+ T helper lymphocytes, often distributed around a Demodex body.[33]

Increased readiness of lymphocytes to undergo apoptosis and increased number of NK cells with Fc receptors is correlated with increased mite density.[34]

Significant decrease in absolute numbers of lymphocytes and T- cell subsets and significant increase in IgM levels have also been found in patients presenting with demodex. Demodex proliferation and facial skin lesions.[35]

Antigenic proteins related to a bacterium isolated from a D. folliculorum mite, Bacillus oleronius, have the potential to stimulate an inflammatory immune response in patients with papulopustular rosacea by increasing the migration, degranulation, and cytokine production abilities of neutrophils.[36,37]

These findings suggest that colonization of the skin with Demodex could be a reflection of immune response of the host to organism.[34]

Clinical manifestation

Demodex mites are present in healthy individuals and may have a pathogenic role only when present in high densities.[13] The infestation may be clinically inapparent, but, under favorable circumstances, these mites may multiply rapidly, leading to the development of different pathogenic conditions.[30,38] All cutaneous diseases caused by Demodex mites are clubbed under the term demodicosis or demodicidosis. Although elevated levels of Demodex occur in such conditions, no studies have proven a definitive relationship. It remains unknown if Demodex is the underlying cause of these conditions or if Demodex mite density increases due to inflammation of affected follicles.[39] It is possible that by blocking the hair follicles, it can cause inflammation or allergic reaction or act as vector for other microorganisms.[40] These conditions are briefly described below:

Rosacea and Demodex rosacea

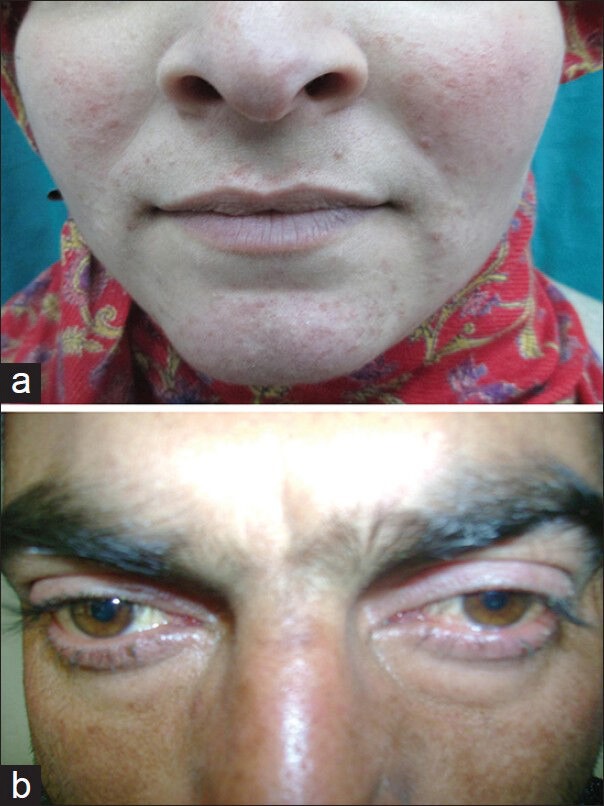

Demodex may have a direct role in rosacea or may manifest as rosacea like dermatitis [Figure 4a]. Numerous studies have reported elevated emodex density in patients with rosacea.[4,10,11,41,42]

Figure 4.

Clinical photograph showing rosacea (a) and steroid induced rosacea (b)

Human demodicosis may manifest as a dry type of rosacea, termed rosacea-like demodicidosis.[43] Rosacea of demodicosis needs to be differentiated from the common rosacea. Demodex type rosacea is characterized by dryness, follicular scaling, superficial vesicles, and pustules, while common rosacea is characterized by oily skin, absent follicular scaling, and being more deeply seated.[44] Another useful feature is the complete resolution of demodicosis on treatment with scabicide crotamiton or lindane. It has been proposed that failure to wash the face and overuse of oily or creamy preparations supplies the Demodex mites with extra lipid nourishment, which promotes reproduction of mites in large numbers, which plugs the pilo-sebaceous ducts and leads to appearance of rosacea-like facial eruption.[45]

Non specific facial dermatitis

Patients presenting with nonspecific facial symptoms such as facial pruritus with or without erythema, a seborrheic dermatitis-like eruption, perioral dermatitis-like lesions and papulopustular, and/or acneiform lesions without telangiectasia, flushing, or comedones have been found to have significantly higher median mite density[39,46] [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Clinical photograph of Demodex induced non specific facial dermatitis

Demodex dermatitis may in fact be distinct from rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis, as reported by one group[47] and the presence of facial erythema, dryness, scaling, and roughness with or without papules/pustules may be a result of D. folliculorum proliferation.[48]

Steroid rosacea

The role of D. folliculorum in the pathogenesis of topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea is controversial.[49,50] It has been reported that the population of Demodex mites is increased in these patients[5,11,51,52] [Figure 4b].

Androgenetic alopecia

Demodex has been implicated in the etiology of AGA.[53] The role of Demodex in AGA has been evaluated to be direct in some studies and indirect in others. The possible mechanisms include the following:

Induction of inflammation by the presence of an immune-active lipase in Demodex mite.[54] Nowadays, inflammation has been considered to be involved in pathogenesis of AGA.[39,55] It has been proposed that inflammation reaction in AGA is confined to the surrounding area of sebaceous glands and infundibulum, and follicular infiltration with activated T cells results in induced synthesis of collagen by dermal sheath fibroblasts and ultimately replacement of hair follicle with fibrosis takes place.[56,57]

Altering local hormone metabolism by the inflammatory reaction.[58]

Sebaceous glands of alopecia-affected hair follicles become larger and more active under the influence of dihydrotestosterone, producing oils at a faster rate and, hence, become a more suitable environment for Demodex. In fact, Demodex infestation is considered to be secondary to AGA and not its cause.

Exhaustion of the hair bulb and shifting of hair cycle from anagen to telogen through long-term invasion by the parasite.[53]

Madarosis

Infestation of pilo-sebaceous components of the eyelids with D. folliculorum can also result in loss of eyelashes.[59] Demodex mite causes follicular inflammation that produces edema and subsequent easier epilation of eyelashes. It also affects cilia constriction so that lashes become brittle and fall.[60]

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei

Several authors suggest that LMDF is a reaction to D. folliculorum; however, a definite association has not been confirmed[61] [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

A case of clinically and histopathologically proven LMDF

Dissecting folliculitis

The cause of dissecting folliculitis of scalp is not well understood [Figure 7]. It is generally considered to be an inflammatory reaction to components of the hair follicle, particularly microorganisms like bacteria (especially Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus aureus), yeasts (M Human Demodex Mite: The Versatile Mite of Dermatological Importance…[62]

Figure 7.

Clinical photograph of dissecting folliculitis leading to cicatricial alopecia

Miscellaneous conditions

Increased number of Demodex mites has also been observed in peri-oral dermatitis [Figure 8a], acarica blepharo-conjuctivitis [Figure 8b], grover's disease, eosinophilic folliculitis, papulovesicular facial, papulopustular scalp eruptions, pityriasis folliculorum, pustular folliculitis, Demodex abscess, and demodicosis gravis (granulomatous rosacea like demodicosis).[34,39,63]

Figure 8.

Clinical photograph of peri-oral dermatitis (a) and blepheritis (b)

Other points of importance

As a vector for transmission

Demodex may act as a vector of transmission of various infections from one area of body to another or between individuals by its potential to ingest and transport various microorganisms that are found in its niche, as demonstrated by potassium hydroxide mount of skin scraping from a mycotic plaque, which showed numerous Demodex mites containing spores of Microsporum canis inside them.[64]

Defense against bacteria

Similar to bacterial flora found on human skin, follicle mites have been shown to contain immune-reactive lipase,[54] which can produce free fatty acids from sebum triglycerides. Therefore, follicle mites could play a role in the defense of human skin against pathogenic bacteria, particularly against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.[65]

Prevention/treatment of human demodicosis

Demodex can only live in the human hair follicle and, when kept under control, causes no problems. However, to reduce the chance of the mites proliferating excessively, following preventive measures are important:

Cleanse the face twice daily with non-soap cleanser

Avoid oil-based cleansers and greasy makeup

Exfoliate periodically to remove dead skin cells.

After clinical manifestations, the mites may be temporarily eradicated with topical insecticides, especially crotamiton cream, permethrin cream, and also with topical or systemic metronidazole. In severe cases, such as those with HIV infection, oral ivermectin may be recommended.[3,48,66]

Conclusion

Human demodicosis is caused by the clinical manifestation of otherwise asymptomatic infestation of humans by two species of Demodex mite, i.e., D. folliculorum and D. brevis. The etiological role of this versatile mite should be kept in mind as human demodicosis can present as a variety of clinical manifestations mimicking many other dermatoses. This can help in early diagnosis and proper treatment, thereby saving time and at the same time being cost effective.

What is new?

Demodex mite should be considered as an aetiological factor for a number of dermatoses for their early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Norn MS. Demodex folliculorum. Incidence, regional distribution, pathogenicity. Dan Med Bull. 1971;18:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rufli T, Mumcuoglu Y. The hair follicle mites Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis: Biology and medical importance. A review. Dermatologica. 1981;162:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000250228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baima B, Sticherling M. Demodicidosis revisited. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:3–6. doi: 10.1080/000155502753600795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aylesworth R, Vance C. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis in cutaneous biopsies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;7:583–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basta- Juzbasic A, Subic JS, Ljubojevic S. Demodex folliculorum in development of dermatitis rosaceiformis steroidica and rosacea-related diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:135–40. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(01)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spickett SG. Studies on Demodex folliculorum Simon. Parasitology. 1961;51:181–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akbulatova LK. The pathogenic role of Demodex mite and the clinical form of demodicosis in man. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1963;40:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns DA. Follicle mites and their role in disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:152–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forton F. Dιmodex and perifollicular inflammation in man: Review and report of 69 biopsies. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1986;113:1047–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forton F, Seys B. Density of Demodex folliculorum in rosacea: A case-control study using standardized skin-surface biopsy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:650–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnar E, Eustace P, Powell FC. The Demodex mite population in rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:443–8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forton F, Song M. Limitations of standardized skin surface biopsy in measurement of the density of Demodex folliculorum: A case report. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:697–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbagci Z, Ozgoztasi O. The significance of Demodex folliculorum density in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:421–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zomorodian K, Geramishoar M, Saadat F, Tarazoie B, Norouzi M, Rezaie S. Facial demodicosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:121–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sengbusch HG, Hauswirth JW. Prevalence of hair follicle mites, Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis (Acari: Demodicidae), in a selected human population in western New York, USA. J Med Entomol. 1986;23:384–8. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/23.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delfos NM, Collen AF, Kroon FP. Demodex folliculitis: A skin manifestation of immune reconstitution disease. AIDS. 2004;18:701–2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin CD, Underwood JC. Demodex infestation of oral mucosal sebaceous glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:80–2. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks R, Dawber RP. Skin surface biopsy: An improved technique for the examination of the horny layer. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:117–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb06853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: Etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gothe R. Demodicosis of dogs–a factorial disease? Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1989;102:293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boge-Rasmussen T, Christensen JD, Gluud B, Kristensen G, Norn MS. Demodex folliculorum hominis (Simon): Incidence in a normomaterial and in patients under systemic treatment with erythromycin or glucocorticoid. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:454–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellerich U, Metzelder M. Incidence of scalp involvement by Demodex folliculorum Simon ectoparasites in a pathologic, anatomic and forensic medicine autopsy sample (in German) Arch Kriminol. 1994;194:111–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caswell JL, Yager JA, Parker WM, Moore PF. A prospective study of the immunophenotype and temporal changes in the histologic lesions of canine demodicosis. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:279–87. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barriga OO, Al-Khalidi NW, Martin S, Wyman M. Evidence of immunosuppression by Demodex canis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;32:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivy SP, Mackall CL, Gore L, Gress RE, Hartley AH. Demodicidosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: An opportunistic infection occurring with immunosuppression. J Pediatr. 1995;127:751–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa T, Sasaki M, Fujita K, Nishimoto M, Takaiwa T. Demodex folliculitis on the trunk of a patient with mycosis fungoides. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:148–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrizi A, Trestini D, D’Antuono A, Colangeli V. Demodicidosis in a child infected with acquired immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Pediat Dermatol. 1999;9:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benessahraoui M, Paratte F, Plouvier E, Humbert P, Aubin F. Demodicidosis in a child with xantholeukaemia associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:311–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akilov OE, Mumcuoglu KY. Association between human demodicosis and HLA class I. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:70–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu CK, Hsu MM, Lee JY. Demodicosis: A clinicopathological study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:453–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temnikov VE. The peculiarity of immune status in rosacea. Nigniy Novgorod. 1991;1:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrosjan EA, Petrosjan VA. The treatment of rosacea complicated by demodicosis by extracorporal modification blood of sodium hypochloritis. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1996;2:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rufli T, Buchner SA. T-cell subsets in acne rosacea lesions and the possible role of Demodex folliculorum. Dermatologica. 1984;169:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000249558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akilov OE, Mumcuoglu KY. Immune response in demodicosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:440–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Bassiouni SO, Ahmed JA, Younis AI, Ismail MA, Saadawi AN, Bassiouni SO. A study on Demodex folliculorum mite density and immune response in patients with facial dermatoses. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2005;35:899–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lacey N, Delaney S, Kavanagh K, Powell FC. Mite-related bacterial antigens stimulate inflammatory cells in rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:474–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Reilly N, Bergin D, Reeves EP, McElvaney NG, Kavanagh K. Demodex-associated bacterial proteins induce neutrophil activation. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:753–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaur T, Jindal N, Bansal R, Mahajan BB. Facial demodicidosis: A diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:72–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.92688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vollmer RT. Demodex-associated folliculitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:589–91. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roihu T, Kariniemi AL. Demodex mites in acne rosacea. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:550–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1998.tb01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Shazly AM, Ghaneum BM, Morsy TA, Aaty HE. The pathogenesis of Demodex follicularum (hair follicular mites) in females with and without rosacea. J Egypt SOC Parasitol. 2001;31:867–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgala S, Katoulis AC, Kylafis GD, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E, Georgala C, Aroni K. Increased density of Demodex folliculorum and evidence of delayed hypersensitivity reaction in subjects with papulo pustulor Rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayres S, Jr, Ayres S., III Demodectic eruptions (demodicidosis) in the human. 30 year’ experience with two commonly unrecognized entities: Pityriasis folliculorum (Demodex) and acne rosacea (Demodex type) Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:816–27. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1961.01580110104016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasan M, Siddiqui FA, Naim M. Human demodicidosis. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2008;1:70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayres S., Jr Demodex folliculorum as a pathogen. Cutis. 1986;37:441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karincaoglu Y, Bayram N, Aycan O, Esrefoglu M. The clinical importance of Demodex folliculorum presenting with nonspecific facial signs and symptoms. J Dermatol. 2004;31:618–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pallotta S, Cianchini G, Martelloni E, Ferranti G, Girardelli CR, Di Lella G, et al. Unilateral demodicidosis. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:191–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bikowski JB, Del Rosso JQ. Demodex Dermatitis: A retrospective analysis of clinical diagnosis and successful treatment with topical crotamiton. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:20–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoekzema R, Hulsebosh HJ, Bos JD. Demodicidosis or rosacea: What did we treat? Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:294–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ljubojeviae S, Basta JA, Lipozeneiae J. Steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea: Aetiopathogenesis and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:121–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00388_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rathi SK, Kumrah L. Topical corticosteroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis: A clinical study of 110 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:42–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.74974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saraswat A, Lahiri K, Chatterjee M, Barua S, Coondoo A, Mittal A, et al. Topical corticosteroid abuse on the face: A prospective, multicenter study of dermatology outpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:160–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zari J, Abdolmajid F, Masood M, Vahid M, Yalda N. Evaluation of the relationship between androgenetic alopecia and Demodex infestation. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:64–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.41647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jimenez-Acosta F, Planas L, Penneys N. Demodex mites contain immuno reactive lipase. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1436–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1989.01670220134028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahé YF. Inflammatory perifollicular fibrosis and alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:416–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaworsky C, Kligman AM, Murphy GF. Characterization of inflammatory infiltrates in male pattern androgenetic alopecia: Implication for pathogenesis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:239–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whiting DA. Diagnostic and predictive value of horizontal sections of scalp biopsy specimen in male pattern androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:755–63. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millikan LE. Androgenetic alopecia: The role of inflammation and Demodex. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:475–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01173-4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clifford CW, Fulk GW. Association of diabetes, lash loss and Staphylococcus aureus with infestation of eyelids by Demodex folliculorum (Acari: Demodicidae) J Med Entomol. 1990;27:467–70. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sachdeva S, Prasher P. Madarosis: A dermatological marker. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:74–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.38426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehta V, Balachandran C, Mathew M. Skin-colored papules on the face. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:368. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tchernev G. Folliculitis et perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens controlled with a combination therapy: Systemic antibiosis (Metronidazole Plus Clindamycin), dermatosurgical approach, and high-dose isotretinoin. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:318–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pena GP, Andrade Filho JS. Is Demodex really non-pathogenic? Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2000;42:171–3. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652000000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolf R, Ophir J, Avigad J, Lengy J, Krakowski A. The hair follicle mites (Demodex spp.): Could they be vectors of pathogenic microorganisms? Acta Derm Venereol. 1988;68:535–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Namazi MR. A possible role for human follicle mites in skin's defense against bacteria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:270. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.33646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gamborg Nielsen P. Metronidazole treatment in rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]