Abstract

Dioscorea species is a very important food and drug plant. The tubers of the plant are extensively used in food and drug purposes owing to the presence of steroidal constituent's diosgenin in the tubers. In the present study, we report for the first time that the leaves of Dioscorea composita and Dioscorea floribunda grown under the field conditions exhibited the presence of multicellular oil glands on the epidermal layers of the plants using stereomicroscopy (SM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Essential oil was also isolated from the otherwise not useful herbage of the plant, and gas chromatographic-mass spectroscopy analysis revealed confirmation of the essential oil constituents. Out of the 76 compounds detected in D. floribunda and 37 from D. composita essential oil, major terpenoids which are detected and reported for Dioscorea leaf essential oil are α-terpinene, nerolidol, citronellyl acetate, farnesol, elemol, α-farnesene, valerenyl acetate, and so forth. Elemol was detected as the major constituent of both the Dioscorea species occupying 41% and 22% of D. Floribunda and D. composita essential oils, respectively. In this paper, we report for the first time Dioscorea as a possible novel bioresource for the essential oil besides its well-known importance for yielding diosgenin.

1. Introduction

Dioscorea commonly referred to as yam is a monocotyledonous tuber plant of the family Dioscoreaceae with about 600 species recorded so far. Different species originate from different parts of the world: Africa, Asia, the Caribbean's South America, and the South Pacific islands, and so forth. The dominant zone for yam production in the world is in West Africa [1], where about 48 million tonnes (about 93% of the world's production) are cultivated on 4 million hectares annually, and mainly in five countries—Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo (FAO, 2005) feeding about 100 million people in the tropics [1]. The more domesticated and cultivated ones are native to Africa [2]. Yams, especially the wild species: D. floribunda, D. composita, D. dumetorum, and D. villosa, and so forth are essentially orphan crops and are therefore classified as neglected and under-utilised species (NUS) due to the fact that though they are rich in nutrients, phytochemicals [3], they are also important in strategies to alleviate biotic and abiotic stresses linked to climate change and are important in traditional pharmacology but yet are adapted to low input agriculture. Yam extracts are emerging as good candidates for the treatment of certain illnesses, for example, menopausal symptoms and some forms of cancer [4]. It is also suggested that yam might reduce the risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular diseases in postmenopausal women [4]. Essential oils usually occur as mono- and sesquiterpenoids in plants and are important commodities and used for centuries medicinally and as cosmetics [5]. The oil glandular trichomes are the primary sites of essential oil biosynthesis [6–10]. Multicellular peltate and single celled capitate glands contribute significantly to the biosynthesis and accumulation of essential oil content [8, 9, 11]. Essential oils with therapeutic effects have been reported in tubers of some yam species: D. alata, rhizomes of D. japonica [12]. Metabolic engineering of monoterpene biosynthesis in the model plant tomato and peppermint has resulted in increase in yield and compositional improvement of the essential oil and also provided strategies for manipulating flavor and fragrance production, as well as plant defense [5, 8, 13, 14]. The qualitative, quantitative, and interspecific variations in essential oil constituents have been reported to occur for several plant species in earlier reports [15–17].

In the present study, we attempted to determine if the diosgenin yielding Dioscorea species possess essential oil in their aerial parts and also the nature and contents of essential-oil and oil glands bearing the essential oil in two species of Dioscorea, namely, D. composita and D. floribunda leaves and vines. The study will aid in the search for and development of novel elemol (Figure 1) rich essential oil of Dioscorea chemotypes and/or species.

Figure 1.

Structure of elemol.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The plants of Dioscorea composita and D. floribunda were obtained from the experimental farm at Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow) in May 2010, Lucknow (26.5°N latitude, 80.5°E longitude), 120 m above mean sea level, subtropical, semiarid zone for the studies.

2.2. Stereomicroscopic and Scanning Electron Microscopic Analysis of Leaf

For stereomicroscopic observation and analysis of glandular trichomes from two species of Dioscorea, namely, D. composita and D. floribunda, fresh leaf samples were taken. Both the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces were processed as described earlier [8]. The processed leaf sample was mounted on clean labelled microscope slide. Leaf impression is studied under a Leica model SM starting at magnification from 100x to 400x for quantitative and qualitative analysis. For SEM analysis, the leaf and vine samples were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (with 0.02% Triton X-100) overnight at 4°C. Three washes (each after 5 minutes duration) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 were given to clean the material. Subsequently, dehydration was followed as 1X 10 minutes in 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol. Finally samples are left in the 100% ethanol solution. Samples were air-dried under a light bulb and were mounted onto metal stubs with double-sided carbon tape. Samples were then subjected to automated sputter coater which applies a thin layer of metals, gold and palladium over them for about 10 minutes.

2.3. Extraction and Gas Chromatographic Analysis of Essential Oil

30 g fresh leaves were collected over ice and hydro-distilled using Clevenger type apparatus to obtain the essential oil for GC/MS analysis as described earlier [8]. The conditions for GC-MS were as follows: a set of sample (D. floribunda and D. composita) specific conditions for the GC-MS, utilized a Perkin Elmer AutoSystem XL GC interfaced with a TurboMass Quadrupole mass spectrometer fitted with an Equity-5 fused silica capillary column (60 m × 0.32 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 μm; Supelco Bellefonte, PA, USA). The oven temperature program ranged from 70°C to 250°C, programmed at 3°C/min, with initial and final hold time of 2 min, carrier gas: He at 10 psi constant pressure, a split ratio of 1 : 40; injector, transfer line, and source temperatures were kept at 250°C; ionization energy 70 eV; mass scan range 40–450 amu. Characterization was achieved on the basis of retention time, elution order, coinjection with standard elemol in GC-FID capillary column (Aldrich and Fluka), mass spectra library search (NIST/EPA/NIH version 2.1, and Wiley registry of mass spectral data 7th edition).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stereomicroscopic (SM) and Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) Analysis of Dioscorea Species

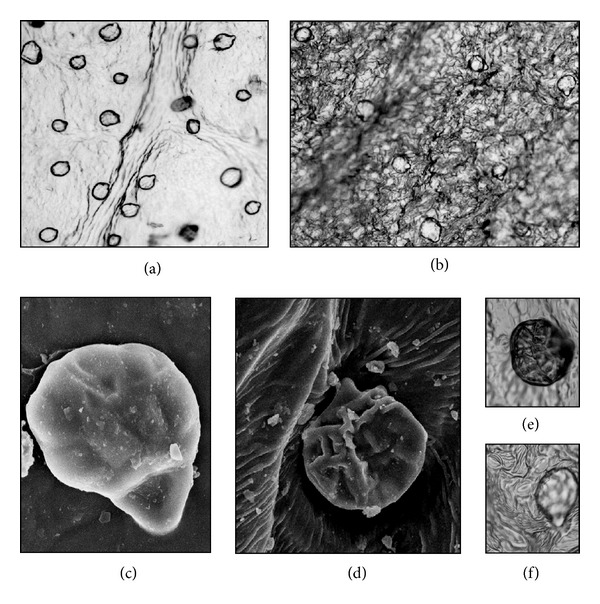

The multicellular peltate oil glands were observed on both D. composita and D. floribunda, with the gland head supported by a stalk cell protruding from the basal cells of the leaves and vines (Figure 2). The population of oil glands on the abaxial surface of D. composita appears more than that on D. floribunda on the basis of the observations on the oil gland count under microscope. The leaves from D. composita yielded about 0.014% (w/w), while D. floribunda yielded slightly higher quantity (0.016% w/w) of essential oil.

Figure 2.

(a) and (b): stereomicroscopic picture of D. composita and D. floribunda essential-oil glandular trichomes at 100x, respectively. (c) and (d): scanning electron microscopic picture of D. composita and D. floribunda essential-oil glandular trichomes at 2.74 kkX, respectively. (e) and (f): 400x stereomicroscopic views of magnifications of essential-oil glandular trichomes of D. composita and D. floribunda, respectively. All were viewed abaxially.

3.2. Essential Oil Composition of Dioscorea Species

A total of 76 compounds were detected from the GC-MS of D. floribunda and most were in trace amounts, while in D. composita, a total of 37 compounds were detected, and like in D. floribunda most of the constituents were present in trace amounts. Mostly sesquiterpenes were detected (85% of essential oil) in D. composita and (48% in essential oil) in D. floribunda essential oils. The overall monoterpene content was detected in traces in both of the Dioscorea species. The % of elemol in D. composita was recorded as 41.02% of total terpenoid, while it is 22.88% of total terpenoid contents in case of D. floribunda leaves (Tables 1 and 2). However, elemol remained as a major oil constituent in both of the Dioscorea species. This communication describes evidence of multicellular peltate oil glands on the leaves and vines of the Dioscorea species and also exhibits existence of novel oil constituent in its essential oil. The anatomical studies with SM and SEM clearly show the presence of essential oil glands in both the species. Also, GC-MS results revealed elemol to be the most abundant essential oil constituent. This compound is a sesquiterpene alcohol with a green woody sweet odour. Of the terpenoids, only members of the mono-(C10) and sesquiterpenoid (C15) classes are sufficiently volatile [18]. Elemol has been reported as an important terpenoid constituent with insecticidal properties [19]. The SM and SEM reveal higher abundance of the oil glands on the abaxial leaf surface of both species and more so in D. composita than in D. floribunda leaves. It is speculated that, evolutionarily, the peltate glands might represent an advanced structure of ecological significance in accumulation and functionality of volatile secondary metabolites [6]. Lack of programmed gland/cuticular dehiscence in capitate glands together with their limited oil-sequestration capacity might put them as a sort of “primitive” oil glands or secretory trichomes which originated from nonglandular trichomes in a phylogenetic sequence [6]. As an evolutionary link in the transition from capitate to peltate glands, some plant species possess capitate glands with more than one secretory head cell, and capitate glands in some plant species possess exocytotic mechanisms of emission of volatiles through rudimentary rupture mode [19]. It has been reported that the β-elemol and α-terpineol achieved 100% termite mortality at the dosage of 1 mg/g after 7 d of testing [20, 21]. Thus, β-elemol and α-terpineol have been shown to possess commendable antitermitic activity [20, 21].

Table 1.

Major essential oil constituents, their retention time, and MS data for Dioscoria composita and Dioscorea floribunda. Different libraries such as Wiley, Nbs, and Nist were used for identification of compounds.

| Plant | Peak no | Lib | Time (mins) | Compound | MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. composita | 2 | W | 9.85 | terpinene | 39,44,65,77,91,93,105,121,136,137 |

| 3 | W | 9.85 | terpinene 1,3-cyclohexadiene, 1 methyl-4-methylethy | 27,39,77,91,93,105,121,136,137 | |

| 3 | N | 30.6 | Butylated hydroxytoluene | 29,41,57,91,105,115,145,177,205,220,221 | |

| 4 | W | 30.6 | Phenol 1,6 Bis (1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl-cas | 41,57,81,105,145,177,205,220,221 | |

| 4 | W | 38.87 | Nerolidol | 53,55,69,79,93,119,133,161,204,205 | |

| 4 | W | 37.57 | Citronellyl acetate | 43,67,69,81,95,123,138 | |

| 5 | W | 9.85 | terpinene 1,3-cyclohexadiene, 1 methyl-4-methylethyl-4 | 27,39,77,91,93,105,121,136,137 | |

| 5 | W | 38.87 | Farnesol | 39,41,55,69,93,107,119,133,161,204 | |

| 5 | Nbs | 37.35 | Dodecyl acrylate | 41,55,56,73,83,97,111,140,168 | |

| 5 | Nbs | 37.57 | Doecadien-1-ol | 41,55,69,81,95,123,181,224 | |

| 6 | W | 37.35 | 2- Decenal | 41,43,55,57,70,83,97 | |

| 6 | W | 37 | 3-Isopropenyl | 43,55,77,91,105,121,131,161,189,204,205 | |

| 6 | W | 37.17 | Selina-3,7 (11)-Diene | 29,41,55,81,91,107,122,133,161,189,204,205 | |

| 10 | W | 32.47 | Elemol | 41,67,68,81,93,107,121,161,189,204,222 | |

| 11 | W | 32.47 | β-elemene | 51,53,67,81,93,107,147,161,189,190 | |

| 15 | Nbs | 39.75 | α-farnesene | 29,41,55,69,93,107,119,135,161,204 | |

| 16 | N | 39.75 | 1,3,6,10-Dodecatetraene | 41,55,69,93,119,120,161,189,204 | |

|

| |||||

| D. floribunda | 3 | W | 38.9 | Farnesol | 39,41,55,69,93,107,119,133,161,204 |

| 3 | W | 36.62 | Torreyol | 39,41,43,81,93,105,119,133,161,162,204,205 | |

| 4 | Nbs | 38.9 | 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol | 39,41,55,69,93,107,119,133,161,204 | |

| 4 | W | 36.62 | Isoledene | 39,41,55,81,91,105,119,133,161,162,204,205 | |

| 4 | W | 34.72 | Aromadendrene | 41,55,69,91,93,105,133,161,189,204,205 | |

| 4 | W | 37.17 | Selina-3,7(11)-diene | 29,41,55,81,91,107,122,133,161,189,204,205 | |

| 4 | W | 37.35 | Dodecanol | 41,43,55,69,70,83,97,111,140,168,169 | |

| 4 | N | 9.87 | Cyclohexene | 27,39,53,79,91,93,105,121,136,137 | |

| 5 | N | 34.72 | 2,4,4-Trimethyl-3B hydroxymethyl | 67,69,77,91,107,121,135,189,207 | |

| 5 | W | 42.92 | 1,6,6-Trimethyl-10 oxatricyclo [8.1.0]undec-3yn-2-ol | 40,41,43,77,91,95,121,123,177,220 | |

| 5 | W | 9.87 | α-terpinene | 41,77,91,93,119,121,136,137 | |

| 7 | W | 36.2 | Cadinene | 27,41,55,81,91,105,119,133,161,162,189,204,205 | |

| 7 | W | 46.12 | 1,H-dimethyl-7 | 41,59,77,91,105,131,159,162,202,203 | |

| 8 | W | 36.47 | Torreyol | 39,41,43,81,93,105,119,133,161,162,204,205 | |

| 8 | W | 46.12 | 1,8-Anhydro-cis-α-copaene-8-ol | 41,77,91,119,145,159,187,202,203 | |

| 9 | W | 36.47 | 4-Iodobis bicycle[2.2.1] hexane | 77,79,91,105,133,161,288,289 | |

| 10 | W | 36.97 | α-cadinol | 71,81,95,105,121,134,161,162,204,205,223 | |

| 10 | W | 32.52 | Elemol | 41,67,68,81,93,107,121,161,189,204,222 | |

| 10 | W | 45.52 | Deoxycapsidiol | 41,55,77,91,105,119,159,173,187,202,220 | |

| 11 | W | 42.8 | 7-1-Methyl-ethenyl-1-hydroxy-1,4-dimethyl | 41,43,79,91,105,145,162,173,202,205,223 | |

| 11 | N | 32.52 | γ-Elemene | 39,41,55,67,79,93,121,136,161,189,204 | |

| 11 | N | 45.52 | 1H-cyclopropa [A] naphthalene | 41,43,55,77,91,131,159,187,202 | |

| 13 | W | 44.82 | Valerenyl acetate | 41,43,55,79,91,105,107,145,160,161,187,202,203 | |

Table 2.

Essential oil constituents and their percentages in oil from Dioscorea composita and Dioscorea floribunda.

| RT | Constituent name | Molecular formula | Type of constituent | % in D. composita | % in D. floribunda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.87 | Alpha terpinene | C10H16 | Monoterpene | 0.45 | 0.06 |

| 30.6 | Butylated hydroxytoluene | C15H24O | Sesquiterpene | 7.57 | 2.68 |

| 32.47 | Elemol | C15H26O | Sesquiterpene | 41.02 | 22.88 |

| 32.52 | Elemene | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 0.33 | 0.31 |

| 34.72 | Aromadendrine | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 0.82 | 0.04 |

| 36.2 | Naphthalene | C15H26 | Sesquiterpene | 3.71 | 2.48 |

| 36.45 | Torreyol | C15H26O | Sesquiterpene | 3.91 | 2.45 |

| 36.62 | Alpha copaene | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| 36.97 | Azulene | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 2.12 | 2.31 |

| 37.17 | Selinene | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 4.32 | 9.57 |

| 37.35 | Dodecyl acrylate | C15H28O2 | Sesquiterpene | 0.95 | 0.19 |

| 37.57 | Citronellyl acetate | C12H22O2 | Monoterpene | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| 38.87 | Farnesol | C15H26O | Sesquiterpene | 14.81 | 0.65 |

| 39.75 | Farnesene | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | 0.64 | 0.18 |

| 42.80 | Gamma-costol | C15H24O | Sesquiterpene | 1.51 | 1.45 |

| 42.92 | Beta-costol | C15H24O | Sesquiterpene | 0.76 | 0.78 |

| 44.82 | Valerenyl acetate | C17H26O2 | Sesquiterpene | 0.69 | 0.55 |

| 45.52 | 1-Deoxycapsidiol | C15H24O | Sesquiterpene | 0.58 | 0.43 |

| 46.12 | 1,8-Anhydro-cis-alpha-copaene-8-ol | C15H22 | Sesquiterpene | 0.49 | 0.66 |

The novel results from this study will facilitate the development of Dioscorea as a high value plant and encourage further research on it for increment of the essential oil through genetic engineering or otherwise in order to help the people living in areas where it grows abundantly and who also happen to be one of the world's poorest peoples [14]. The study will aid in the search and development of novel elemol rich essential oil of Dioscorea chemotypes and/or species. It may also be possible to utilize the waste herbage for the antitermite molecule elemol which is present in high proportions after the Dioscorea tubers are taken out.

4. Conclusions

This communication describes for the first time evidence of multicellular peltate oil glands on the leaves of the Dioscorea composita and D. floribunda and also exhibits existence of novel oil constituent elemol in its essential oil by GC-MS. Elemol has been reported as an important terpenoid constituent with insecticidal and antitermite properties. D. composita with about 41% of elemol in its essential oil could be one of the best sources for elemol rich essential oil, if the efforts are made to express essential oil in leaves in higher amounts. The results reveal that Dioscorea in addition to its well-known usage of its tubers as food and drug crop can also be an important elemol rich essential oil bearing plant.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Joy I. Odimegwu is grateful to Third World Organization of Women in Science (TWOWS) for funding Ph.D. studentship under TWOWS-CSIR, India sandwich programme. The authors thank the Director of CSIR-Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants and Head of Department of Structural and Molecular Biology Unit for constant encouragement and support. Ritesh K. Yadav thanks UGC for the senior research fellowship. CSIR network project NWP 09 and ChemBio (BSC 203) are duly acknowledged for the financial assistance to carry out the research. The authors also thank Head Gene bank and CIMAP for plant material.

References

- 1.Asiedu R, Sartie A. Crops that feed the world 1. Yams. Food Security. 2010;2(4):305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozo ON, Caygill JC, Coursey DG. Phenolics of five yam (Dioscorea) species. Phytochemistry. 1984;23(2):329–331. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su PF, Li CJ, Hsu CC, et al. Dioscorea phytocompounds enhance murine splenocyte proliferation ex vivo and improve regeneration of bone marrow cells in vivo . Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:11 pages. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq032.731308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu W-H, Liu L-Y, Chung C-J, Jou H-J, Wang T-A. Estrogenic effect of yam ingestion in healthy postmenopausal women. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2005;24(4):235–243. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sangwan NS, Farooqi AHA, Shabih F, Sangwan RS. Regulation of essential oil production in plants. Plant Growth Regulation. 2001;34(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, Sangwan NS, Sangwan RS. Developmental process of essential oil glandular trichome collapsing in menthol mint. Current Science. 2003;84(4):544–550. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanker S, Ajayakumar PV, Sangwan NS, Kumar S, Sangwan RS. Essential oil gland number and ultrastructure during Mentha arvensis leaf ontogeny. Biologia Plantarum. 1999;42(3):379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose SK, Yadav RK, Mishra S, et al. Effect of gibberellic acid and calliterpenone on plant growth attributes, trichomes, essential oil biosynthesis and pathway gene expression in differential manner in Mentha arvensis L. Plant Physiology et Biochemistry. 2013;66:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh N, Luthra R, Sangwan RS. Oxidative pathways and essential oil biosynthesis in the developing Cymbopogon flexuosus leaf. Plant Physiology et Biochemistry. 1990;28:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangwan RS, Sangwan NS. Metabolic and molecular analysis of chemotypic diversity in aromatic grasses (Cymbopogon spp.) In: Kumar S, Dwivedi S, Kukreja AK, Sharma JR, Bagchi GD, editors. Aromatic Grass Monograph. Lucknow, India: CIMAP; 2000. pp. 223–247. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis D, Bonner L, Johnson CB. UV-B is required for normal development of oil glands in Ocimum basilicum L. (sweet basil) Annals of Botany. 2002;90(4):453–460. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gramshaw JW, Osinowo FAO. Volatile components of cooked tubers of the water yam Dioscorea alata . Journal of Science Food Agriculture. 1982;33(1):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmoud SS, Croteau RB. Strategies for transgenic manipulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in plants. Trends in Plant Science. 2002;7(8):366–373. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangwan NS, Sangwan RS. Metabolic engineering for flavour enhancement in tomato-path setting for opportunities and strategies. Current Science. 2007;93(7):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sangwan NS, Yadav U, Sangwan RS. Genetic diversity among elite varieties of the aromatic grasses, Cymbopogon martinii . Euphytica. 2003;130(1):117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farooqi AHA, Sangwan NS, Sangwan RS. Effect of different photoperiodic regimes-on growth, flowering and essential oil in Mentha species. Plant Growth Regulation. 1999;29(3):181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sangwan RS, Farooqi AHA, Bansal RP, Singh-Sangwan N. Interspecific variation in physiological and metabolic responses of five species of Cymbopogon to water stress. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1993;142(5):618–622. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gounaris Y. Biotechnology for the production of essential oils, flavours and volatile isolates: a review. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 2010;25(5):367–386. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krings M, Taylor TN, Kellogg DW. Touch-sensitive glandular trichomes: a mode of defence against herbivorous arthropods in the Carboniferous. Evolutionary Ecology Research. 2002;4(5):779–786. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng S-S, Lin C-Y, Chung M-J, Chang S-T. Chemical composition and antitermitic activity against Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki of Cryptomeria japonica leaf essential oil. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 2012;9(2):352–358. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201100243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll JF, Paluch G, Coats J, Kramer M. Elemol and amyris oil repel the ticks Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) in laboratory bioassays. Experimental and Applied Acarology. 2010;51(4):383–392. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]