Abstract

Purpose

Irinotecan is a cytotoxic agent with activity against gliomas. Thalidomide, an antiangiogenic agent, may play a role in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). To evaluate the combination of thalidomide and irinotecan, we conducted a phase II trial in adults with newly-diagnosed or recurrent GBM.

Patients and methods

Thalidomide was given at a dose of 100 mg/day, followed by dose escalation every 2 weeks by 100 mg/day to a target of 400 mg/day. Irinotecan was administered on day 1 of each 3 week cycle. Irinotecan dose was 700 mg/m2 for patients taking enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants and 350 mg/m2 for all others. The primary endpoint was tumor response, assessed by MRI. Secondary endpoints were toxicity, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

Results

Twenty-six patients with a median age of 55 years were enrolled, with fourteen evaluable for the primary outcome, although all patients were included for secondary endpoints. One patient (7%) exhibited a partial response after twelve cycles, and eleven patients (79%) had stable disease. The intention to treat group with recurrent disease included 16 patients who had a 6-month PFS of 19% (95% CI: 4–46%) and with newly-diagnosed disease included 10 patients who had a 6-month PFS of 40% (95% CI: 12–74%). Gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity was mild, but six patients (23%) experienced a venous thromboembolic complication. Two patients had Grade 4 treatment-related serious adverse events that required hospitalization. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Conclusion

The combination of irinotecan and thalidomide has limited activity against GBM. Mild GI toxicity was observed, but venous thromboembolic complications were common.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Clinical trial, Glioblastoma multiforme, Irinotecan, Thalidomide

Introduction

Despite aggressive therapy, nearly all patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) will die of their disease [1]. Following years of negative clinical trials with cytotoxic therapies, temozolomide was recently shown to significantly prolong survival when combined with radiation in initial treatment of these patients [2]. It is unlikely that a single agent will result in eradication of GBM and combinations of drugs with different anti-neoplastic mechanisms have the potential to augment response. By combining cytotoxic and cytostatic agents it may be possible to enhance activity against the tumor without worsening side effects [3].

Irinotecan (Camptosar®) and its active metabolite, SN-38, have activity against multiple solid tumors cell lines, including glioblastoma [4]. Toxicity in patients with recurrent malignant glioma is less than that observed in patients with colorectal cancer, probably because the concomitant use of enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants (EIA) results in low plasma concentrations from increased drug clearance [5]. Phase I data for irinotecan in patients with recurrent GBM has established an MTD of 350 mg/m2 for patients not receiving EIA, but 750 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for those receiving EIA [6]. Initial phase II data for single agent irinotecan revealed a 15% response rate in 60 patients with recurrent high grade glioma [5]. More recent studies published after our trial was completed suggest that single agent irinotecan has minimal activity against GBM [7, 8].

Thalidomide (Thalomid®) has demonstrated activity against a variety of malignancies, including: myeloma, renal cell carcinoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and GBM [9]. In a phase II study, Fine et al. treated 36 patients with recurrent high-grade glioma with thalidomide escalated by 200 mg/day every 2 weeks to a final daily dose of 1200 mg; there were two partial responders, two minor responders, and 12 patients with stable disease. Eight patients were alive greater than 1 year after starting thalidomide, although the majority had tumor progression [10]. Similarly, Marx et al. started patients at a dose of 100 mg/day and escalated to 500 mg/day [11]. Of 38 evaluable patients, two achieved response and 16 had stabilization. Assessment of Quality of Life (QOL) and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) showed stabilization or improvement in the group of patients with stable or responding disease.

The combination of thalidomide and irinotecan has been used in treatment of metastatic colon cancer. A Phase I–II study treated with irinotecan at a dose of 300–350 mg/m2every 3 weeks and thalidomide at a dose of 400 mg/day without any severe gastrointestinal toxicity (GI) toxicity [12]. In animal models, the concomitant administration of irinotecan with thalidomide did not significantly alter the plasma pharmacokinetics of the former drug [13]. In the setting of relapsed GBM, thalidomide has modest activity which seems enhanced when combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy [14]. Given that each of these agents has activity against GBM and that the combination could increase efficacy with decreased toxicity, we undertook a phase II clinical trial.

Methods

This was an open-label, two institution study of irinotecan/thalidomide following radiotherapy for the treatment of patients with GBM. All patients had previously undergone surgical resection or biopsy leading to diagnosis. Prior to enrollment, all patients had been treated with conformal external beam radiotherapy. Additionally, patients who had evidence of disease progression or relapse after chemotherapy were eligible for participation if at least 4 weeks had elapsed since the last treatment with chemotherapy. Eligible patients were ≥18 years with a KPS ≥ 60 and histologically confirmed glioblastoma. Patients were required to have evidence of enhancing disease on contrast-enhanced MRI performed within four weeks of enrollment. For patients with newly diagnosed disease, enhancement on MRI scan done within 4 weeks of completing radiation therapy was required. For patients with progression or recurrence, enhancing disease was required by MRI scan following completion of radiation therapy and one prior chemotherapy regimen. Repeat biopsy was not required, although efforts were made to distinguish tumor from radiation necrosis including magnetic resonance spectroscopy and thallium single photon emission tomography. Patients on corticosteroids must have been on a stable or decreasing dose for 1 week prior to entry. Adequate hematologic, renal and hepatic function parameters were required. Patients of childbearing potential were required to have a negative pregnancy test before starting treatment and to use contraception while on study. All patients were required to enroll in the FDA-mandated System for Thalidomide Education and Prescription Safety (S.T.E.P.S.®) Program. Patients provided signed informed consent in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines. The trial was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of Dartmouth College, Clinical Cancer Research Committee of the Norris Cotton Cancer Center, and the institutional review board of Ohio State University Medical Center.

Treatment was initiated with irinotecan at a dose of 350 mg/m2 or 700 mg/m2, if the patient was on EIA, and thalidomide at a dose of 100 mg/day. Thalidomide was increased as tolerated, by 100 mg/day every 2 weeks to a maximum dose of 400 mg/day. No other chemotherapy or experimental anticancer medications were permitted while subjects were on study. During therapy, physical examination, Complete Blood Count (CBC) with differential, and chemistry profile were performed 1 week after the first cycle and prior to each subsequent cycle. Pregnancy testing was done as outlined in S.T.E.P.S. Program. Toxicities were graded on a scale of 0–4, using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) version 2.0. Criteria for response were based on those recommended by Macdonald et al. [15]. Patients were reassessed by MRI following three cycles of therapy. Those patients with evidence of response had a confirmatory scan after three additional cycles. Thereafter, a scan was repeated every three cycles. Patients who continued to have benefit following six cycles of therapy continued on protocol at physician discretion. Protocol treatment was discontinued for those patients with evidence of disease progression, but they remained in the study and were included in the intent to treat analysis. Since disease free survival and overall survival were considered secondary endpoints all patients were followed until death.

A two-stage sequential design was used to evaluate treatment with an initial planned enrollment of 14 evaluable patients, followed by an additional ten enrolled if at least one response was observed in the initial cohort. With this design, if the study was stopped early, the data would statistically rule-out response rates of 20% or more with P < 0.05 (one-sided). The total sample size of 24 patients would provide a confidence interval for the response rate having a half-width of at most ±20%. Time from study enrollment to disease progression and death were assessed using the product-limit method.

Results

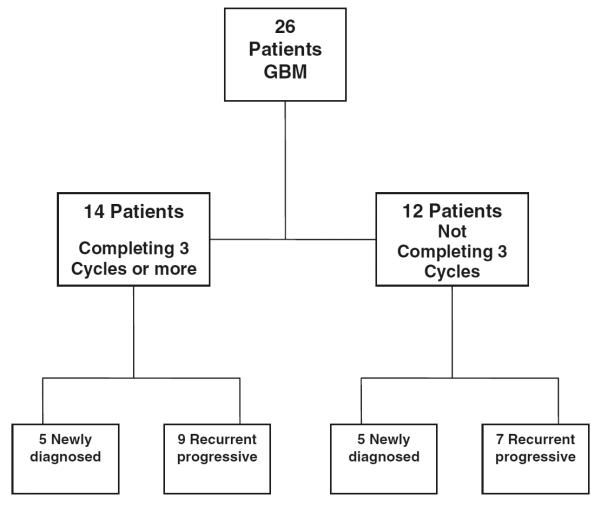

Between March 2002 and November 2004, 26 patients enrolled onto study. Their characteristics are listed in Table 1. The distribution of the patients as primary or recurrent is shown in Fig. 1. All patients were considered evaluable for toxicity. Twelve patients were considered non-evaluable for response due to withdrawal prior to completing three cycles of therapy. Reasons for withdrawal are described in Table 2. Of 14 evaluable patients, there were eleven with stable disease (SD) and three with progression after three cycles. Five patients with SD withdrew from protocol before completing six cycles: two due to deep venous thrombosis (DVT), two due to personal decision, and one with compression fracture with severe back pain and clinical deterioration. All six patients who completed the six cycles of therapy had SD on MRI at that time point. One patient with recurrent disease had a partial response (PR) after 12 cycles that persisted until 17 cycles when progressive disease was observed. This patient had a second surgical resection with pathology revealing recurrent tumor. Another patient with newly diagnosed GBM had SD for 14 cycles before progression. The study was terminated because there were no responses at the specified time interval (at least a PR following three cycles). Best response achieved was a PR after 12 cycles. Given the single responding patient after 12 cycles, the response rate is 7% (1 of 14 patients; 95% CI: 0–34%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Newly diagnosed | Recurrent disease | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 10 | 16 | 26 |

| Age at enrollment, years | |||

| Median | 58 | 54 | 57 |

| Range | 41–75 | 30–72 | 30–75 |

| KPS | |||

| Median | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Range | 70–90 | 70–90 | 70–90 |

| Extent of Resection | |||

| Biopsy | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Partial | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Complete | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Number of Prior Chemotherapy Regimens | |||

| 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| 1 | 15 | 15 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Days from diagnosis to start of study treatment | |||

| Median | 95 | 288 | |

| Range | 90–105 | 133–1,605 | |

| Percentage of patients completing 3 cycles or more | 50 | 56 | 54 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of patients enrolled

Table 2.

Reason and time of withdrawal for 12 non-evaluable patients

| Reason | <1 Cycle | 1 Cycle | 2 Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sedation | 1 | ||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 3 | ||

| Neurologic deterioration | 1 | ||

| Compliance | 1 | ||

| Patient decision | 1 | ||

| Progressive disease | 1 | 1 |

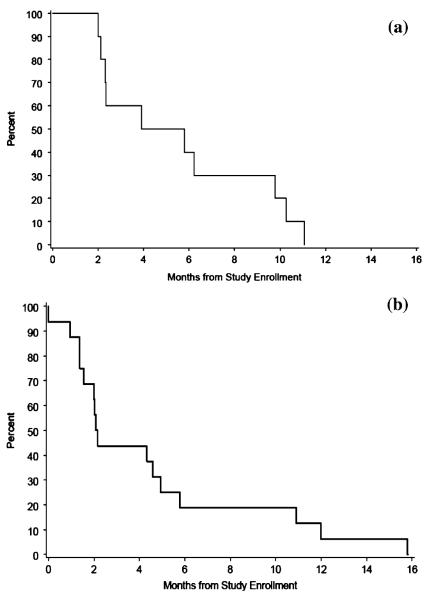

The median overall survival for the intention-to-treat group was 10.2 months and the 6-month progression-free survival (PFS) was 27% (95% CI: 12–48%). The intention to treat group with recurrent disease included 16 patients who had a 6-month PFS of 19% (95% CI: 4–46%) and with newly-diagnosed disease included 10 patients who had a 6-month PFS of 40% (95% CI: 12–74%) (Fig. 2a). For the nine evaluable patients treated for recurrent disease, the median PFS was 4.6 months and the 6-month PFS was 22% (95% CI: 3–60%) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Progression free survival curves for intention to treat patients with (a) newly diagnosed (10 patients) GBM and (b) recurrent (16 patients) GBM

Summary of severe adverse events and toxicities encountered is shown in Table 3. There was no difference in adverse events for patients receiving EIA. Thromboembolic complications were diagnosed in six patients including five DVT and one pulmonary embolism. One patient experienced sedation with thalidomide which prevented him from completing the first cycle of treatment. There were no treatment related deaths.

Table 3.

Serious adverse events and possible relation to treatment according to irinotecan dose

| All events | Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 350 mg/m2 | 700 mg/m2 | 350 mg/m2 | 700 mg/m2 | |

| Likely | ||||

| Neutropenia | 5 | 1 | ||

| Nausea/vomit | 1 | 1 | ||

| Infection | 1 | |||

| Constipation | 1 | |||

| Diarrhea | 1 | |||

| Somnolence/fatigue | 1 | |||

| Anorexia | 1 | |||

| Possible | ||||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 3 | 2 | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | |||

| Seizures | 1 | |||

| Increased ALT | 1 | |||

| Colitis | 1 | |||

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | |||

| Unlikely | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 3 | 1 | ||

| Dysphagia | 1 | 2 | ||

| Headaches | 1 | |||

| Compression | 2 | |||

| Fracture/Pain | ||||

| Pain/Abdominal | 1 | |||

| Neurologic deterioration | 1 | |||

| Weakness | 1 | |||

| Tremor | 1 | |||

| Cushingoid | 1 | |||

Discussion

Although the combination of irinotecan and thalidomide for treatment of GBM was appealing, we observed minimal activity in the population studied. Moreover, 27% of enrolled patients did not complete the first three cycles of therapy because of treatment related adverse effects. Prolonged cytostatic effect was not apparent as all patients had evidence of progressive disease. When data including only patients with recurrent disease was analyzed, there was no improvement in the 6 month PFS compared to reported data for phase II trials [16] or when compared to data obtained using irinotecan alone [8].

In this preliminary Phase II trial, response rate was used as the primary outcome to overcome the potential shortfall of including patients with both newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM. Radiation therapy can transiently increase contrast enhancement in patients with GBM that in some cases improves or stabilizes without treatment [17]. This could lead to a false response rate in phase II trials, but that was not the case here since there were no responses in the newly diagnosed group. Most phase II studies for recurrent GBM use 6 month PFS as the primary outcome especially when a cytostatic agent is being evaluated [16]. Fine at al. changed the primary outcome of their study using thalidomide for GBM from time to tumor progression to objective radiographic response, after evidence of early response [10]. Puduvalli et al. reported a 6% response rate and a 6 month PFS of 25% in 32 patients with recurrent GBM using a regimen of irinotecan 125 mg/m2 weekly times 4, followed by 2 weeks off treatment, and thalidomide 100 mg daily escalated to 400 mg [18]. In the recurrent disease group included in our study, PFS and overall survival were disappointing compared to the historic data. [16]. Therefore, we conclude that the use of response rate as the primary outcome and the inclusion of patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent disease do not limit the validity of our results.

Several recent studies underscore the difficulties of defining the optimum dose of irinotecan for patients with malignant glioma [19–21], The interaction between irinotecan and inducers of the CYP450 system is well recognized [20, 21]. The variability in response and toxicity associated with irinotecan, although explained in part by drug-drug interaction in patients on EIA, is probably also related to inter-patient differences in the drug metabolism [22, 23] and tumor resistance [24]. It has been suggested that because of the wide variance in MTD the dose should be individualized by dose escalating to MTD for the individual patient [19]. In our study, patients were dosed according to the concomitant use of EIA and there was no difference seen in response between those on EIA or not.

The dose of single agent thalidomide for treatment of recurrent GBM has varied widely. A response rate of 6% was seen at doses up to 1,200 mg/day [10]. Similar response rates have been seen at lower doses, suggesting absence of dose-response effect [11, 25]. It is unclear if combination of thalidomide with other chemotherapy agents might enhance activity. In a study combining BCNU and thalidomide the response rate for recurrent GBM was 24% [14]. In contrast, two studies examining temozolomide and thalidomide in the recurrent setting showed a disappointing response rate of 7–8% [26, 27]. Therefore, the addition of thalidomide to temozolomide or irinotecan does not appear to offer an advantage over the use of either drug alone.

Several reports describe increased tolerability of irinotecan when given with thalidomide [28]. Although we found that the frequency and severity of GI toxicity was less then expected there were a high number of venous thromboembolic (VTE) complications. This finding suggests that the therapy increased the risk, already high in this patient population, of developing a venous vascular event. Almost one quarter of the patients in this study developed symptomatic thromboembolic complications that appeared after starting therapy. Thalidomide alone is not associated with VTE but the risk appears to increase when combined with other chemotherapeutic agents [14, 29]. Several studies have looked at the potential role of anticoagulation in preventing VTE in patients receiving thalidomide for multiple myeloma but there is no consensus yet as to what intervention would be most appropriate [30–37]. Overall toxicity in this study suggests an inability to further dose escalate and that the absence of response was not the result of under dosing.

Single agent irinotecan, thalidomide, or the combination of both drugs has minimal antineoplastic activity against GBM. These agents in combination exhibit fairly significant toxicity and any further study does not seem justified. Preliminary studies combining irinotecan with bevacizumab, an antibody targeting vascular endothelial growth factor, have shown response rates that compare favorably with those obtained with other combinations including irinotecan [38–40]. The contribution of irinotecan to the responses observed with this combination is unclear.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 8th Annual SNO Meeting in Keystone, CO, November 13–16, 2003.

References

- 1.McLendon RE, Halperin EC. Is the long-term survival of patients with intracranial glioblastoma multiforme overstated? Cancer. 2003;98:1745–1748. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11666. doi:10.1002/cncr.11666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Govindarajan R, Heaton KM, Broadwater R, et al. Effect of thalidomide on gastrointestinal toxic effects of irinotecan. Lancet. 2000;356:566–567. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02586-1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02586-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakatsu S, Kondo S, Kondo Y, et al. Induction of apoptosis in multi-drug resistant (MDR) human glioblastoma cells by SN-38, a metabolite of the camptothecin derivative CPT-11. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;39:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s002800050592. doi:10.1007/s002800050592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman HS, Petros WP, Friedman AH, et al. Irinotecan therapy in adults with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1516–1525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prados MD, Yung WK, Jaeckle KA, et al. Phase 1 trial of irinotecan (CPT-11) in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. Neuro-oncol. 2004;6:44–54. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000292. doi:10.1215/S1152851703000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batchelor TT, Gilbert MR, Supko JG, et al. Phase 2 study of weekly irinotecan in adults with recurrent malignant glioma: final report of NABTT 97–11. Neuro-oncol. 2004;6:21–27. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000218. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prados MD, Lamborn K, Yung WK, et al. A phase 2 trial of irinotecan (CPT-11) in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. Neuro-oncol. 2006;8:189–193. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2005-010. doi:10.1215/15228517-2005-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajkumar SV, Witzig TE. A review of angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapy with thalidomide in multiple myeloma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:351–362. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0188. doi:10.1053/ctrv.2000.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine HA, Figg WD, Jaeckle K, et al. Phase II trial of the antiangiogenic agent thalidomide in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:708–715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marx GM, Pavlakis N, McCowatt S, et al. Phase II study of thalidomide in the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:31–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1012554328801. doi:10.1023/A:1012554328801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govindarajan R. Irinotecan/thalidomide in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncology (Huntingt) 2002;16:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Hu Z, Chan SY, et al. Simultaneous determination of the lactone and carboxylate forms of irinotecan (CPT-11) and its active metabolite SN-38 by high-performance liquid chromatography: application to plasma pharmacokinetic studies in the rat. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;821:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.05.010. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fine HA, Wen PY, Maher EA, et al. Phase II trial of thalidomide and carmustine for patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2299–2304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.045. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, et al. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong ET, Hess KR, Gleason MJ, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in recurrent glioma patients enrolled onto phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2572–2578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wit MC, de Bruin HG, Eijkenboom W, et al. Immediate post-radiotherapy changes in malignant glioma can mimic tumor progression. Neurology. 2004;63:535–537. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133398.11870.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puduvalli VK, Giglio P, Groves MD, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan and thalidomide in adults with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncol. 2008;10:216–222. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-060. doi:10.1215/152285172007-060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloughesy TF, Filka E, Kuhn J, et al. Two studies evaluating irinotecan treatment for recurrent malignant glioma using an every-3-week regimen. Cancer. 2003;97:2381–2386. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11306. doi:10.1002/cncr.11306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert MR, Supko JG, Batchelor T, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of irinotecan in adults with recurrent malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2940–2949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamberlain MC. Salvage chemotherapy with CPT-11 for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2002;56:183–188. doi: 10.1023/a:1014532202188. doi:10.1023/A:1014532202188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai AA, Innocenti F, Ratain MJ. Pharmacogenomics: road to anticancer therapeutics nirvana? Oncogene. 2003;22:6621–6628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206958. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innocenti F, Liu W, Chen P, et al. Haplotypes of variants in the UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 1A9 and 1A1 genes. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:295–301. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200505000-00004. doi:10.1097/01213011-200505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker RJ, Fruehauf JP, Mehta R, et al. A prospective blinded study of the predictive value of an extreme drug resistance assay in patients receiving CPT-11 for recurrent glioma. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:365–375. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000014549.77646.f6. doi:10.1023/B:NEON.0000014549.77646.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short SC, Traish D, Dowe A, et al. Thalidomide as an anti-angiogenic agent in relapsed gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2001;51:41–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1006414804835. doi:10.1023/A:1006414804835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang SM, Lamborn KR, Malec M, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide with radiation therapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.023. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groves MD, Puduvalli VK, Chang SM, et al. A North American brain tumor consortium (NABTC 99-04) phase II trial of temozolomide plus thalidomide for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9225-y. doi:10.1007/s11060-006-9225-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Hu Z, Chan SY, et al. Determination of thalidomide by high performance liquid chromatography: plasma pharmacokinetic studies in the rat. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2005;39:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.041. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krown SE, Niedzwiecki D, Hwu WJ, et al. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic melanoma in the brain: high rate of thromboembolic events (CALGB 500102) Cancer. 2006;107:1883–1890. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22239. doi:10.1002/cncr.22239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller KC, Padmanabhan S, Dimicelli L, et al. Prospective evaluation of low-dose warfarin for prevention of thalidomide associated venous thromboembolism. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2339–2343. doi: 10.1080/10428190600799631. doi:10.1080/10428190600799631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zangari M. Anticoagulation regimens for thalidomide and lenalidomide. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4:658–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajkumar SV, Blood E. Lenalidomide and venous thrombosis in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2079–2080. doi:10.1056/NEJMc053530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight R, DeLap RJ, Zeldis JB. Lenalidomide and venous thrombosis in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2079–2080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc053530. doi:10.1056/NEJMc053530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikhlaque N, Seshadri V, Kathula S, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic warfarin for prevention of thalidomide-related deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:420–422. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20625. doi:10.1002/ajh.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajkumar SV. Thalidomide therapy and deep venous thrombosis in multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1549–1551. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baz R, Li L, Kottke-Marchant K, et al. The role of aspirin in the prevention of thrombotic complications of thalidomide and anthracycline-based chemotherapy for multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1568–1574. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minnema MC, Breitkreutz I, Auwerda JJ, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism with low molecular-weight heparin in patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide and chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2004;18:2044–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403533. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope WB, Lai A, Nghiemphu P, et al. MRI in patients with high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab and chemotherapy. Neurology. 2006;66:1258–1260. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000208958.29600.87. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000208958.29600.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, 2nd, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multi-forme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang TY, Jin T, Elinzano H, et al. Irinotecan and bevacizumab in progressive primary brain tumors, an evaluation of efficacy and safety. J Neurooncol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9599-0. doi:10.1007/s11060-008-9599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]