Abstract

BACKGROUND

There is limited data on the impact of anti-retroviral treatment (ART) initiation on alcohol consumption. We characterized predictors of abstaining from alcohol among HIV-infected individuals following ART initiation.

METHODS

We analyzed data from a prospective cohort of HIV-infected adults in Mbarara, Uganda with quarterly measures of self-reported alcohol consumption, socio-demographics, health status, and blood draws. We used pooled logistic regression to evaluate predictors of becoming abstinent from alcohol for at least 90 days after baseline.

RESULTS

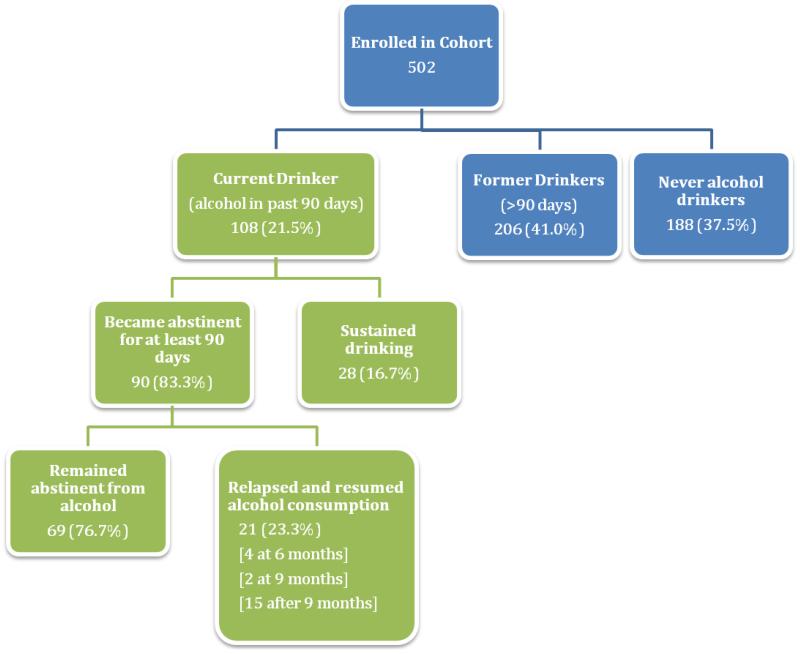

Among the 502 participants, 108 (21.5%) were current drinkers who consumed alcohol within 90 days of baseline, 206 (41.0%) were former drinkers, and 188 (37.5%) were lifetime abstainers at baseline. Among current drinkers, 67 (62.0%) drank at hazardous levels. 90 of current drinkers (83.3%) abstained from alcohol at least for 90 days over 3.6 median years of follow-up [IQR 2-4.8]; of those 69 (76.7%) remained abstinent for a median duration of follow-up of 3.25 years [1.6-4.5]. Becoming abstinent was independently associated with lower baseline AUDIT score (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.95[95%CI 0.91-0.99]), baseline physical health score (AOR 0.92[0.87-0.97]), and decreases in physical health score at follow-up visits (AOR 0.92[0.88-0.97)). Alcohol abstinence was most likely to start immediately after ART initiation (AORs for 6 month versus 3 month visit: 0.25[0.10-0.61]; 9 month visit or later versus 3 month visit: 0.04[0.02-0.09]).

CONCLUSIONS

We found that a large majority of drinkers starting ART reported that they became and remained abstinent from alcohol. ART initiation may be an opportune time to implement interventions for alcohol consumption and other health behaviors.

Keywords: Alcohol, HIV, alcohol abstinence, hazardous drinking, ART-initiation, antiretroviral treatment, Uganda, Africa

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2010, five and a half percent of the total burden of disease around the world has been attributed to alcohol consumption, which is also causally related to more than 60 chronic and acute health conditions (Lim et al., 2012; Room et al., 2005). Heavy alcohol use, in particular, has been associated with a wide range of societal, economic, and medical consequences (Lee and Forsythe, 2011; Room et al., 2005; Tumwesigye et al., 2012b).

Hazardous alcohol consumption is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA; World Health Organization, 2011a). Per-capita, Uganda has among the highest alcohol consumption in the world (World Health Organization, 2011a). One study in primary care clinics in Kampala, Uganda observed a 17% and 10% prevalence of hazardous alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence, respectively (Kullgren et al., 2009). Despite the high prevalence of heavy alcohol use in SSA and in Uganda, interventions to reduce alcohol use are not widespread in this region, particularly outside large urban areas, underscoring a major public health gap (Hahn et al., 2011). Although provision of health education materials and cognitive behavioral therapy may be promising in reducing alcohol consumption among HIV-infected individuals in some settings, scale-up of these programs remain limited (Papas et al., 2011; Peltzer et al., 2013; Pengpid et al., 2013a). Moreover, problem alcohol use is believed to often go undetected in this region; one study in primary care settings found that only 7% of drinkers have been asked about their alcohol consumption by their medical providers (Kullgren et al., 2009).

Alcohol use has been associated with increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission in SSA (Bukenya et al., 2012; Mbulaiteye et al., 2000; Page and Hall, 2009; Seeley et al., 2012; Shuper et al., 2009; Tumwesigye et al., 2012a; Zablotska et al., 2006). There is compelling data linking alcohol consumption and increased sexual risk behaviors—and consequently secondary HIV transmission—in SSA (Kalichman et al., 2007). In addition, alcohol consumption has been associated with delays in detection of HIV-infection, poor HIV health outcomes and sub-optimal HIV care (Fatch et al., 2012; Hahn et al., 2011; Hendershot et al., 2009). Drinking may also play a role in receipt of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and alcohol intoxication may also affect ART efficacy through poor adherence or potential changes in metabolism of ART (Martinez et al., 2008; Braithwaite and Bryant, 2010; Hahn and Samet, 2010; Hendershot et al., 2009). Some, though not all, studies have found independent associations between alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression (Hahn and Samet, 2010; Hahn et al., 2011).

However, little is known about the patterns of alcohol use among HIV-infected individuals in SSA. There is also very limited data on the impact of ART initiation on alcohol consumption. One study in Kampala, Uganda, found that ART initiation was associated with a 50% increase in odds of reporting abstinence from alcohol for at least six months among those with HIV (Hahn et al., 2012b). Given the interplay between HIV and alcohol use, it is important to characterize the extent of alcohol consumption, particularly among HIV-infected individuals, in this region. Moreover, identifying HIV-infected persons who do not become abstinent from alcohol can assist with targeting and development of effective interventions for others to reduce harms associated with alcohol (Hahn et al., 2011). We therefore sought to evaluate alcohol consumption patterns and prospective predictors of self-reported initiation of abstinence from drinking among HIV-infected individuals initiating ART in Mbarara, Uganda.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants and Study Design

Data from this analysis was collected as part of the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes (UARTO) study, a prospective cohort of HIV-infected individuals initiating ART. Participants were eligible for enrollment in this cohort if they were HIV-infected, ART-naïve, at least 18 years of age and lived within 60 kilometers from the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital Immune Suppression Syndrome (ISS) Clinic in Mbarara, Uganda. A representative from the study recruited and screened individuals obtaining antiretroviral medication for the first time from the ISS pharmacy for eligibility. All eligible patients who consented to participate were enrolled in the cohort until the target sample size for the study was reached. In quarterly visits, biological specimens were collected, and participants were interviewed face-to-face with standardized questionnaires administered in English or Runyankole by native speakers.

2.2. Measurements

Data on sociodemographic characteristics and quality of life measures, including mental health summary (MHS) and physical health summary (PHS) were collected in interviewer-administered structured questionnaires. MHS and PHS are two of the domains from the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Survey (MOS-HIV)—a measure of health function that has been previously validated in Uganda (Stangl et al., 2007) and has been associated with AIDS-related events (Wu et al., 1997). MHS and PHS scores range between 0-100, with higher scores corresponding with better function and quality of life. Self-reported alcohol consumption, including frequency and volume was elicited quarterly. At baseline, the World Health Organization’s 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) was administered to assess alcohol consumption from the past 12 months (range:0-40; Saunders et al., 1993). Hazardous alcohol consumption cut-offs for men and women were scores of eight and five, respectively. These cut-offs were observed to have the most optimal sensitivity and specificity for hazardous drinking among men and women in a population-based study in Finland (Aalto et al., 2009). Blood draws were also conducted at quarterly visits for CD4+ T-cell counts. The procedures for this study were approved by the Committee in Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco, Partners HealthCare, Mbarara University of Science and Technology and the Uganda National Council on Science and Technology.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

At baseline, we estimated the proportion of current alcohol drinkers (i.e. those who reported alcohol consumption within the prior 3 months), former alcohol drinkers (i.e. those who reported alcohol consumption over 3 months ago), and lifetime abstainers of alcohol. Among current drinkers at baseline, we fitted a pooled logistic regression (PLR) model to evaluate predictors of time to first becoming abstinent from alcohol for at least 90 days using a complete case analysis. Because the majority of participants reported becoming abstinent at month 3 or 6 visits, time intervals were categorized into 3 groups: 1) month 3 visits (referent), 2) months 6 visits, and 3) months 9 visits or later. PLR is appropriate for outcomes that are interval-censored between visits; furthermore, with the inclusion of the categorical variable for interval in the model, PLR provides estimates of the between-interval differences in the incidence rate for abstinence. We evaluated the relationship between abstaining from drinking and the following: age, sex, education, religion, literacy, and baseline AUDIT score (evaluated as a continuous measure and dichotomized as hazardous vs. non-hazardous). Time-varying predictors of interest were time since ART initiation/baseline visit, MHS score, PHS score, and CD4 cell count. For model-building, we used the algorithm suggested by Hosmer and Lemeshow in which predictors that were statistically significant in the bivariate-level using a p-value cut-off point of 0.25 were included in the larger multivariable model (Bursac et al., 2008). The final multivariable model was arrived at using a step-wise backward procedure; likelihood ratio tests were used to confirm that nested-models fit the data as well as larger models. At year one and two of follow-up, 2% and 5% of UARTO participants were lost to follow-up, respectively. Moreover, 12% of data on alcohol consumption were missing due to missed visits. We therefore conducted multiple imputation using iterative chained equations with STATA 12.1 (College Station, TX) to examine our findings’ sensitivity to missing data. For multiple imputation, missing continuous follow-up data on MHS, PHS, and CD4 count were imputed using predictive mean matching while missing binary data on alcohol consumption was imputed using logistic regression; 10 datasets were imputed using demographic (e.g. education, literacy, religion, gender, age) characteristics, AUDIT score, PHS score, MHS score, and CD4 cell count. The 10 imputed datasets were analyzed using STATA mi estimate, which combines dataset-specific results to estimate standard errors, confidence intervals, and p-values that reflect the imputation of missing data via established methods (Schafer, 1999).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Among the 502 HIV-infected participants enrolled in the UARTO cohort from June 2005 to May 2011, 108 (21.5%) were current drinkers, 206 (41.0%) were former drinkers, and 188 (37.5%) were lifetime abstainers of alcohol (Figure 1). The median number of days between baseline alcohol assessment and ART initiation was 1 day (inter-quartile range: 0-2); 96% of participants initiated ART within 15 days of baseline alcohol assessment. Of the current drinkers at baseline, over half were male (51.9%), most were literate (78.7%), and most only had primary education or lower (63.9%; see Table 1). Among current drinkers, 67 (62.0%) were considered hazardous drinker at baseline by past-year AUDIT score (median 9; IQR: 5-15). The median number of drinking days among current drinkers was 3.5 (IQR: 1-10) and the majority reported drinking less than 5 drinks on a typical drinking day (68.5% had 1 or 2 drinks, 17.6% had 3 or 4). Many have felt guilty about their drinking (37.0%) or the need to cut down on their alcohol consumption (49.1%).

Figure 1.

Alcohol consumption in UARTO Cohort during Baseline and Follow-Up Visits

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of HIV-infected Current Alcohol Drinkers, Former Drinkers, and Never Drinkers initiating ART in Rural Uganda.

| Never Drinkers (Lifetime Alcohol Abstainers, N=188) |

Former Drinkers (Alcohol >90 days of baseline, N=206) |

Current Drinkers (Alcohol within 90 days of baseline, N=108 ) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N median |

(row %) (IQR) |

N median |

(row%) (IQR) |

N median |

(row%) (IQR) |

|

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 33.5 | (27-39) | 35 | (30-40) | 35 | (30-39) |

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 152 | (44.4) | 141 | (41.2) | 49 | (14.3) |

| Male | 34 | (22.5) | 61 | (40.4) | 56 | (37.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Primary or Less | 137 | (40.1) | 136 | (39.8) | 69 | (20.2) |

| Beyond Primary | 45 | (36.9) | 48 | (39.3) | 29 | (23.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Literacy | ||||||

| Illiterate | 38 | (37.6) | 43 | (42.6) | 20 | (19.8) |

| Partial or Fully Literate | 145 | (37.3) | 159 | (40.9) | 85 | (21.9) |

|

| ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Protestant | 97 | (39.0) | 102 | (41.0) | 50 | (20.1) |

| Catholic | 46 | (26.6) | 76 | (43.9) | 51 | (29.5) |

| Moslem | 29 | (70.7) | 9 | (22.0) | 3 | (7.3) |

| Other | 14 | (46.7) | 15 | (50.0) | 1 | (3.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical | ||||||

| CD4 Count, median (IQR) | 131.5 | (76-201) | 134 | (67-192) | 124 | (73.5-217.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Mental Health Score (MOS), median (IQR) † | 52.3 | (44.4-56.6) | 51.0 | (44.2-56.8) | 53.1 | (47.1-59.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Physical Health Score (MOS), median (IQR) † | 53.3 | (42.4-58.6) | 52.2 | (42.0-57.1) | 55.6 | (47.0-59.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline Alcohol Consumption among Current Alcohol Drinkers |

N

median |

[column %]

(IQR) |

||||

|

| ||||||

| Drinking days in past 30 days, median (IQR) | 3.5 | (1-10) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Score – in the past year, median (IQR) | 9 | (5-15) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Hazardous Alcohol Consumption by AUDIT Score | 67 | [62%] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Drinks on a typical day when you were drinking in the past year | ||||||

| 1 or 2 drinks | 74 | [68.5] | ||||

| 3 or 4 drinks | 19 | [17.6] | ||||

| 5 or more drinks | 10 | [9.3] | ||||

| “cannot estimate”§ | 4 | [3.7] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Heavy episodic drinking (having six or more drinks on one occasion) in the past year | ||||||

| Never | 71 | [65.7] | ||||

| Less than monthly | 6 | [5.6] | ||||

| Monthly | 10 | [9.3] | ||||

| Weekly | 7 | [6.5] | ||||

| Daily/mostly daily | 5 | [4.6] | ||||

| “cannot estimate”§ | 8 | [7.4] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Ever hospitalized due to drinking | 3 | [2.8] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Ever attended a 12-step program | 1 | [1.0] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Ever felt they should cut down on drinking | 53 | [49.1] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Ever felt guilty about drinking | 40 | [37.0] | ||||

Notes: Percent may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Measures from Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) health-related quality of life measures in HIV/AIDS; higher scores correspond with better physical or mental health function.

Participants who reported that they “cannot estimate because of use of non standardized non-bottled home-brewed beverages.”

3.2 Longitudinal Analysis

Analyses of becoming abstinent from alcohol were restricted to 108 current drinkers at baseline, who contributed 167.75 person-years of follow-up, with a median follow-up time of 3.6 median years of follow-up [IQR: 2-4.8]. Among the current drinkers, 90 (83.3%) reported first abstaining from alcohol for at least 90 days during follow-up. As illustrated in Figure 2, the majority (n=50) of those who abstained reported doing so during the first 90 days after ART initiation—that is by their 3-month visit. Becoming abstinent was less common later during follow-up; 14 participants became abstinent by 6-month visit and the 26 participants became abstinent by 9-month visit or later. Among the 90 who abstained from alcohol for at least 90 days, 69 participants (76.7%) reported remaining abstinent, while 21 (23.3%) resumed drinking at some point during the course of the 6-year follow-up (4 relapsed at 6 month, 2 at 9 month, and 15 after 9 month). For those who remained abstinent, the median duration of follow up was 3.25 years (IQR = 1.6-4.5).

Figure 2.

Time to first becoming abstinent from alcohol for 90 days among 108 baseline current drinkers

3.3 Multivariable Pooled Logistic Regression

Becoming abstinent from alcohol for at least 90 days was independently associated with lower AUDIT score at baseline (AOR 0.95; 95% CI 0.91-0.99), lower PHS score at baseline (AOR 0.92; 95% CI 0.87-0.97), and decreases in PHS score at follow-up visits (AOR 0.92; 95% CI 0.88-0.97), while controlling for changes in CD4 count during follow-up in multivariable analysis. Participants were also most likely to report alcohol abstinence in the first 90 days immediately after ART initiation (the 3 month visit); becoming abstinent from alcohol was less likely at later visits for those who continue to drink. Participants were most likely to abstain from alcohol during the first three months after ART initiation; among those still at drinking, the odds of abstaining from alcohol by 6 month visits and after 9 months were 0.25 (95% CI 0.10-0.61) and 0.04 (95% CI 0.02-0.09), respectively, compared to the odds of abstaining at month 3. The findings were similar in PLR analysis which used multiple-imputation (Table 2).

Table 2. Pooled Logistic Regression Model for Becoming Abstinent from Alcohol for at least 90 days.

| Complete Case | Multiple Imputation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| ||||

| Visit Interval | ||||

| Month 3 visit | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Month 6 visit | 0.25 (0.10-0.61) | 0.002 | 0.32 (0.13-0.81) | 0.016 |

| Month 9 visit or later | 0.04 (0.02-0.09) | <0.001 | 0.05 (0.02-0.09) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Baseline AUDIT Score (past 12 months)2 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.049 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.042 |

|

| ||||

| Baseline Physical Health Score | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | 0.001 | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Change in Physical Health Score at Follow-up | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | 0.001 | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | 0.001 |

Note Data only shown for statistically significant findings, models also adjusted for changes in CD4 cell count at follow-up

4. DISCUSSION

Among HIV-infected individuals in Uganda, the prevalence of current alcohol use was modest but a high proportion of current drinkers reported drinking at hazardous levels the year prior to ART initiation. This finding is broadly consistent with the high rates of hazardous alcohol consumption among drinkers previously observed in other Ugandan samples overall, and among HIV infected individuals (Fatch et al., 2012; Hahn et al., 2012b; Kullgren et al., 2009). Most significantly, a very large proportion of current drinkers at baseline reported becoming abstinent from alcohol for at least 90 days immediately after initiating ART, and most of those remained abstinent, findings which have not previously been reported.

We found that those with higher AUDIT scores at baseline were more likely to persist in drinking alcohol during follow-up. A three-question alcohol screen at clinic entry using the AUDIT-C, comprised of the first three consumption questions of the AUDIT, is standard procedure in this clinic (Bush et al., 1998). This suggests that further measures to address heavy alcohol consumption may be warranted. In addition, implementing screening for problematic or hazardous alcohol consumption in HIV-treatment clinics where it is not yet standard is vital, since identifying those with alcohol abuse or dependence is the first step toward referrals to/provision of effective treatment (Petry, 1999). Moreover, efforts to develop focused on interventions for hazardous drinkers who continue to drink should be prioritized.

We also observed that individuals with greater improvement in physical function as measured by PHS were less likely to report becoming abstinent from alcohol. It is possible that as perceived physical health improved, participants may have perceived that alcohol no longer posed harm to their health, and consequently continued drinking. Similarly, those who had greater physical health scores at baseline were also less likely to report abstinence from alcohol. It is possible that compared to those with poor physical function, those who had better physical health may not have felt a compelling reason to abstain from alcohol. Conversely, participants with poor physical health may have also abstained from alcohol because they were too ill to drink. This finding is important because ART is increasingly being initiated prior to the onset of symptoms, which suggests that more people may be drinking alcohol while on ART, therefore raising concerns about the effect of alcohol on early ART adherence.

In addition, we observed that among those still at risk, a high proportion of current alcohol drinkers reported abstaining from alcohol immediately after ART initiation. These findings are consistent with another Ugandan study which found that self-reported abstinence from alcohol was associated with ART initiation among HIV-infected individuals (Hahn et al., 2012b). Of note, as drinking continued beyond the first quarterly visit after ART initiation, the likelihood of becoming abstinent from alcohol had decreased dramatically. The reductions in alcohol consumption were concurrent with ART initiation. Those who continued to drink more than three months after they initiated ART were unlikely to ever quit on their own. Interestingly, these reductions in alcohol consumption after ART initiation are mirrored by other health improvements in this same cohort—in UARTO, ART initiation has been associated with increased food security and reductions in depression (Martinez et al., 2012; Weiser et al., 2012). It is possible that initiating ART provides a range of collateral health benefits. Interestingly, these reductions in alcohol consumption after ART initiation are mirrored by other health improvements in this same cohort—in UARTO, ART initiation has been associated with increased food security and reductions in depression (Martinez et al., 2012; Weiser et al., 2012). It is possible that initiating ART provides a range of collateral benefits that are similar to engaging in primary care. Indeed, a prospective study of individuals in a drug/alcohol detoxification unit found that receipt of primary medical care was associated with significant declines in alcohol consumption and severity of use (Saitz et al., 2004) and a similar effect for substance abuse has also been shown (Friedmann et al., 2003). It is possible that engagement in health care and/or discussions about health preserving behaviors have some effect. While motivation to change behavior is the foundation of many brief interventions, many which have been successful, especially in primary care (Kaner et al., 2007), additional studies are needed to understand why those initiating ART reduce their alcohol consumption.

The mechanism behind our findings on alcohol abstinence during follow-up is not completely clear. Two recent randomized controlled trials, one among hospital outpatients (Pengpid et al., 2013) and one among primary care patients with active tuberculosis (Peltzer et al., 2013), compared brief motivational interventions to providing health education information on alcohol consumption. Both studies found equivalent reductions in drinking among both conditions (Peltzer et al., 2013; Pengpid et al., 2013). This suggests that in some settings minimal intervention may be all that is needed; thus information about the effects of alcohol on HIV disease and ART adherence may be sufficient. Counseling to promote ART adherence is conducted by the ISS clinic, and alcohol consumption is sometimes addressed, which may have a positive effect on drinking. At this time, there is no standard protocol in the clinic for patients who drink alcohol. Instead, staff are encouraged to communicate about reduction of alcohol after assessing the levels of consumption, however the delivery of this message may vary widely between staff (Personal Communication: Muyindike, 2013).

Another plausible explanation for declines in drinking is assessment reactivity. Alcohol researchers have previously recognized that participants react to study protocols involving collection of data on alcohol use; more frequent and more comprehensive alcohol assessments have been associated with declines in alcohol consumption and better drinking outcomes (Bien et al., 1993; Clifford and Maisto, 2000; Clifford et al., 2007; Maisto et al., 2007). Researchers posit that the assessment of drinking behavior in itself can lead to reductions in alcohol consumption (Bien et al., 1993; Clifford and Maisto, 2000). In this study, participants were interviewed about their drinking behaviors on a quarterly basis, and research assistants may often be perceived as health care workers. Although study participants were not receiving a formal alcohol intervention, it is likely that at least some individuals were reactive to these assessments and changed their drinking behavior as a result of these regular interviews.

Alternately, participants may also fear that alcohol consumption could be used as an exclusionary criterion from ART receipt and therefore under-report their current alcohol consumption; indeed, health providers have delayed provision of ART among alcohol drinkers due to treatment adherence concerns (McNaghten et al., 2003; Papas et al., 2012). Some of these data were collected during the early stages of large-scale ART roll out, and the perception that ART was being rationed is plausible during the earlier periods of the study. Social desirability bias may also provide at least a partial explanation for our findings (Hahn et al., 2012b). A recent nested-study within UARTO (n=61) observed a two-fold increase in self-reported alcohol consumption when alcohol biomarkers were collected concurrently during alcohol assessment confirm that at least some participants are under-reporting alcohol consumption (Hahn et al., 2012c). Unfortunately, because we did not systematically collect whole blood samples to test for alcohol biomarkers such as phosphatidylethanol (PEth), the extent of under-reporting is unclear across the entire sample. Future studies among HIV-infected individuals should collect specimens for biomarkers of alcohol consumption when possible as they function as complementary objective measures of alcohol use and potentially improve the accuracy of self-reported consumption (Hahn et al., 2010, 2012a, 2012c). Qualitative studies currently underway (JH) may also help determine whether reported reductions in alcohol consumption at this clinic are due to assessment reactivity, the influence of counseling by the staff, concern about the effects of alcohol on ART efficacy, or otherwise. However, because many of our results were consistent with previous findings and decreased levels of becoming abstinent among more hazardous drinkers and those reporting better health (Hahn et al., 2012b), we feel that at least some of the decline in drinking is real.

This study has several limitations. First, the modest number of current drinkers in our sample at time of ART initiation may have reduced our power to detect statistically significant associations and precluded us from evaluating other less common alcohol drinking patterns in the study, such as abstaining and then relapsing to drinking. This may explain the lack of association we observed for other characteristics previously shown to be associated with alcohol abstinence, such as gender and CD4 cell count (Hahn et al., 2012b; Pandrea et al., 2010). However, although we did not observe gender differences for alcohol abstinence among current drinkers, we note that at baseline, women were much less likely to be current drinkers compared to men (14.3% vs. 37.1%), suggesting that women may be more likely to never start drinking and to quit earlier, consistent with the literature. Additionally, the majority of those initiating ART in this study were immunologically quite compromised (i.e., had low CD4 cell count) and this low variance in CD4 cell count at baseline may explain the lack of association with quitting alcohol. Physical health score, which was inversely related to quitting, was a better predictor in this study. Thus, it would be important to replicate this analysis and also explore predictors of stopping and resuming drinking with a larger sample that has greater prevalence of alcohol consumption.

As previously described, the self-reported data used for alcohol consumption are subject to recall and/or social desirability and other reporting biases. However, we believe that self-report has very high (if not perfect) specificity as participants who are not drinking are unlikely to over-report drinking. Compared to outcome measures with poor specificity, effect estimates from analyses with outcome measures with high specificity are less prone to biased estimates, despite imperfect sensitivity (Copeland et al., 1977). Thus, we are confident that the findings from our PLR models are not significantly biased due to possible misclassification of the outcome. Similar to other non-randomized studies, we cannot rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounders in our analysis of correlates of becoming abstinence. Moreover, this study is limited to a sample of HIV-infected individuals who are ART-naïve from a single HIV-treatment clinic. Thus, the findings may not necessarily be generalizable to other populations or settings. An additional limitation is that the time-dependent covariates CD4 count and change in MHS and PHS scores may in part mediate the effect of visit interval, thus understating its importance. Despite these limitations, the findings on self-reported abstinence were consistent between the complete case pooled logistic regression models and multiple imputation sensitivity analyses for missing data, suggesting that these results are robust. In addition, our analytic findings were consistent with the findings of other studies.

These data underscore the need to implement screening tools to increase detection of problematic alcohol consumption in HIV care settings, and intervention approaches (Samet et al., 2004). The findings on the inverse relationship between physical health and alcohol consumption has important implications as countries in SSA begin to implement treatment guidelines that call for earlier initiation of ART. If ART occurs prior to the onset of HIV-related symptoms, alcohol consumption during treatment may become more common, and HIV providers should be aware that more of their patients may be drinking alcohol. Hazardous alcohol use may influence the efficacy of ART through behavioral and biologic pathways and function as a barrier to optimal HIV-care (Braithwaite and Bryant, 2010; Hahn et al., 2011; Hendershot et al., 2009).

Moreover, our study provides insight on the longitudinal alcohol consumption patterns of HIV-infected adults initiating ART and the baseline prevalence of alcohol use in this population. These findings can inform the development of new alcohol interventions in SSA, where hazardous alcohol consumption is common and additional evidence-based interventions outside large urban areas are needed. These data can also inform the targeting and translation of screening and brief interventions for harmful alcohol use—which have been tested in hospital settings, patients with tuberculosis in primary care settings, and in university students in SSA—for HIV-infected individuals (Peltzer et al., 2013; Pengpid et al., 2013a,2013b). Moreover, these results can also facilitate the identification of drinkers who are initiating ART whom may benefit from intensive behavioral interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy—which showed promising results in reducing alcohol consumption among HIV-infected patients in Kenya (Papas et al., 2011). Ideally, these existing evidence-based interventions should be made available to sub-groups who have difficulty abstaining from alcohol, particularly those who have more hazardous alcohol consumption prior to ART initiation and those with good physical health who may not necessarily feel an urgency to reduce their consumption. The data also suggest that ART initiation may be an opportune time to implement additional harm reduction interventions for alcohol consumption. As many patients appear to attempt abstaining from alcohol during this period, many individuals may benefit from additional counseling to reduce relapse or resumption of hazardous drinking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of UARTO for taking part in this study. The study was funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health U01 CA066529, R01 MH-054907 (PI: Bangsberg), and R01 AA-018631 (PI: Hahn). The authors acknowledge the following additional sources of support: R36 DA-035109A (Santos).

Role of Funding Source: Nothing declared.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict declared.

Author Disclosures:

Contributors:

GMS executed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. JAH conceptualized the study and assisted in drafting the manuscript. EV and ARM assisted in the analysis. JNM, DIB, JAH conceived and designed the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aalto M, Alho H, Halme JT, Seppä K. AUDIT and its abbreviated versions in detecting heavy and binge drinking in a general population survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88:315–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Res. Health. 2010;33:280–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukenya J, Vandepitte J, Kwikiriza M, Weiss HA, Hayes R, Grosskurth H. Condom use among female sex workers in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2012;25:767–774. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.748863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Biol. Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA. Subject reactivity effects and alcohol treatment outcome research. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:787–793. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part I. Alcohol use and related consequences. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:519–528. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1977;105:488–495. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatch R, Bellows B, Bagenda F, Mulogo E, Weiser S, Hahn JA. Alcohol consumption as a barrier to prior HIV testing in a population-based study in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2012;17:1713–1723. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0282-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Bwana MB, Javors MA, Martin JN, Emenyonu NI, Bangsberg DR. Biomarker testing to estimate under-reported heavy alcohol consumption by persons with HIV initiating ART in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1265–1268. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9768-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Dobkin LM, Mayanja B, Emenyonu NI, Kigozi IM, Shiboski S, Bangsberg DR, Gnann H, Weinmann W, Wurst FM. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) as a biomarker of alcohol consumption in HIV-positive patients in sub-Saharan Africa. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012a;36:854–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Fatch R, Baveewo S, Choi JE, Bangsberg DR, Kamya M, Wanyenze R, Coates TJ. Reductions in Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption After HIV Testing in Uganda; Conference on Retrovirueses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. 2012b. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Fatch R, Kabami J, Mayanja B, Emenyonu NI, Martin J, Bangsberg DR. Self-report of alcohol use increases when specimens for alcohol biomarkers are collected in persons With HIV in Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012c;61:e63–64. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318267c0f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Woolf-King SE, Muyindike W. Adding fuel to the fire: alcohol’s effect on the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:172–180. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;52:180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev. Sci. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007;2:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullgren G, Alibusa S, Birabwa-Oketcho H. Problem drinking among patients attending primary healthcare units in Kampala, Uganda. Afr. J. Psychiatry (Johannesbg.) 2009;12:52–58. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v12i1.30279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GA, Forsythe M. Is alcohol more dangerous than heroin? The physical, social and financial costs of alcohol. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2011;19:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, Chafe Z, Charlson F, Chen H, Chen JS, Cheng AT, Child JC, Cohen A, Colson KE, Cowie BC, Darby S, Darling S, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dentener F, Des Jarlais DC, Devries K, Dherani M, Ding EL, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Edmond K, Ali SE, Engell RE, Erwin PJ, Fahimi S, Falder G, Farzadfar F, Ferrari A, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Fowkes FG, Freedman G, Freeman MK, Gakidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannucci E, Gmel G, Graham K, Grainger R, Grant B, Gunnell D, Gutierrez HR, Hall W, Hoek HW, Hogan A, Hosgood HD, 3rd, Hoy D, Hu H, Hubbell BJ, Hutchings SJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacklyn GL, Jasrasaria R, Jonas JB, Kan H, Kanis JA, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Khang YH, Khatibzadeh S, Khoo JP, Kok C, Laden F, Lalloo R, Lan Q, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Li Y, Lin JK, Lipshultz SE, London S, Lozano R, Lu Y, Mak J, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Marcenes W, March L, Marks R, Martin R, McGale P, McGrath J, Mehta S, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Micha R, Michaud C, Mishra V, Mohd Hanafiah K, Mokdad AA, Morawska L, Mozaffarian D, Murphy T, Naghavi M, Neal B, Nelson PK, Nolla JM, Norman R, Olives C, Omer SB, Orchard J, Osborne R, Ostro B, Page A, Pandey KD, Parry CD, Passmore E, Patra J, Pearce N, Pelizzari PM, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pope D, Pope CA, 3rd, Powles J, Rao M, Razavi H, Rehfuess EA, Rehm JT, Ritz B, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Romieu I, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Roy A, Rushton L, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Sapkota A, Seedat S, Shi P, Shield K, Shivakoti R, Singh GM, Sleet DA, Smith E, Smith KR, Stapelberg NJ, Steenland K, Stockl H, Stovner LJ, Straif K, Straney L, Thurston GD, Tran JH, Van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Veerman JL, Vijayakumar L, Weintraub R, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams W, Wilson N, Woolf AD, Yip P, Zielinski JM, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Clifford PR, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part II. Treatment engagement and involvement. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:529–533. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Andia I, Emenyonu N, Hahn JA, Hauff E, Pepper L, Bangsberg DR. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms and the receipt of antiretroviral therapy in southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:605–612. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Tsai A, Muzoora C, Kembabazi A, Weiser S, Huang Y, Haberer J, Martin J, Bangsberg D, Hunt P. Reversal of IDO-induced Tryptophan Catabolism May Mediate ART-related Improvements in Depression in HIV+ Ugandans; 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mbulaiteye SM, Ruberantwari A, Nakiyingi JS, Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Whitworth JA. Alcohol and HIV: a study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000;29:911–915. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaghten AD, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Jones JL. Differences in prescription of antiretroviral therapy in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2003;32:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, Hall CP. Psychosocial distress and alcohol use as factors in adolescent sexual behavior among sub-Saharan African adolescents. J. Sch. Health. 2009;79:369–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandrea I, Happel KI, Amedee AM, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Alcohol’s role in HIV transmission and disease progression. Alcohol Res. Health. 2010;33:203–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas RK, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S, Bryant KJ, Meslin EM, Sidle JE. Ethical issues in a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral therapy feasibility study and trial to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics. 2012;7:29–37. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.3.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas RK, Sidle JE, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S, Mwaniki MM, Songole R, Omolo OE, Kamanda AM, Ayuku DO, Ojwang C, Owino-Ong’or WD, Harrington M, Bryant KJ, Carroll KM, Justice AC, Hogan JW, Maisto SA. Treatment outcomes of a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral trial to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected out-patients in western Kenya. Addiction. 2011;106:2156–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Louw J, Matseke G, Zuma K, McHunu G, Tutshana B, Mabaso M. Screening and brief interventions for hazardous and harmful alcohol use among patients with active tuberculosis attending primary public care clinics in South Africa: results from a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:699. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Skaal L, Van der Heever H. Screening and brief interventions for hazardous and harmful alcohol use among hospital outpatients in South Africa: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013a;13:644. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengpid S, Peltzer K, van der Heever H, Skaal L. Screening and brief interventions for hazardous and harmful alcohol use among university students in South Africa: results from a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013b;10:2043–57. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10052043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Alcohol use in HIV patients: what we don’t know may hurt us. Int. J. STD AIDS. 1999;10:561–570. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365:519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Phillips SJ, Horton NJ, Traphagen ET, Freedberg KA. Detecting alcohol problems in HIV-infected patients: use of the CAGE questionnaire. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2004;20:151–155. doi: 10.1089/088922204773004860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Horton NJ, Larson MJ, Winter M, Samet JH. Primary medical care and reductions in addiction severity: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2005;100:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1999:8. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, Mpendo J, Asiki G, Abaasa A, De Bont J, Nielsen L, Kaleebu P, Team CS. High HIV incidence and socio-behavioral risk patterns in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2012;39:433–439. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318251555d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, Rehm J. Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1021–1036. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl AL, Wamai N, Mermin J, Awor AC, Bunnell RE. Trends and predictors of quality of life among HIV-infected adults taking highly active antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2007;19:626–636. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumwesigye NM, Atuyambe L, Wanyenze RK, Kibira SP, Li Q, Wabwire-Mangen F, Wagner G. Alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviour in the fishing communities: evidence from two fish landing sites on Lake Victoria in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2012a;12:1069. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumwesigye NM, Kyomuhendo GB, Greenfield TK, Wanyenze RK. Problem drinking and physical intimate partner violence against women: evidence from a national survey in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2012b;12:399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Gupta R, Tsai AC, Frongillo EA, Grede N, Kumbakumba E, Kawuma A, Hunt PW, Martin JN, Bangsberg DR. Changes in food insecurity, nutritional status, and physical health status after antiretroviral therapy initiation in rural Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012;61:179–186. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318261f064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Wu AW, Revicki DA, Jacobson D, Malitz FE. Evidence for reliability, validity and usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV) Qual. Life Res. 1997;6:481–493. doi: 10.1023/a:1018451930750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotska IB, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, Kigozi G, Sewankambo N, Lutalo T, Mangen FW, Wawer M. Alcohol use before sex and HIV acquisition: a longitudinal study in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20:1191–1196. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226960.25589.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]