Abstract

Background and Purpose

The need for surgical feeding tube placement after acute stroke can be uncertain and associated with further morbidity.

Methods

Retrospective data were recorded and compared across patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). We identified all feeding tubes placed as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes (PEG). A prediction score for PEG tube placement was developed separately for AIS and ICH patients using logistic regression models of variables known by 24 hours from admission.

Results

Of 407 patients included, 51 (12.5%) underwent PEG tube placement (25 AIS and 26 ICH). The odds of an AIS patient with PEG score ≥3 of getting a PEG are greater than those with PEG score <3 (Odds Ratio 15.68, 95% CI 4.55-54.01). The odds of an ICH patient with PEG score ≥3 of getting a PEG are greater than those with PEG score <3 (Odds Ratio 12.49, 95% CI 1.54-101.29).

Conclusions

The PEG score, comprised by variables known within the first day of admission, may be a powerful predictor of PEG placement in patients with acute stroke.

Keywords: Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy, PEG, surgical feeding tube, acute ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage

Introduction

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, can be identified in up to fifty percent of patients with acute stroke.1-3 The placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is a feasible and common medical intervention with a low complication rate4 for patients who suffer from dysphagia following stroke to minimize complications.5 This study aims to develop a score to assist physicians in predicting the eventual placement of a PEG in patients who suffer from acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from patients admitted consecutively with acute stroke (AIS and ICH) to our academic stroke center from 07/2008-12/2010. Patients who received a PEG tube or other surgical feeding tube during hospital stay were identified from our stroke registry database. Patients with an in-hospital stroke, transferred from an outside facility, with an unknown time of last seen normal (LSN), reason for dysphagia other than stroke (e.g., multiple sclerosis, advanced Alzheimer’s dementia, or previous head and neck surgery), and who presented 24 hours after LSN were excluded. Admission demographic and clinical data as well as outcome measures were extracted from patient records. Demographic and clinical data were recorded from within 24 hours of presentation and compared across patients with AIS and ICH using Chi square and t-test with nonparametric tests, as well as odds ratios (OR), when appropriate. A prediction score was developed separately for AIS and ICH patients. More information on data collection, statistical analyses and prediction model building can be found in the online supplementary file.

Results

Patient population

A total of 734 patients were identified for the study, 407 patients met inclusion criteria. Of these patients 51 (12.5%) underwent PEG placement during hospital admission (Table 1). Of those undergoing PEG placement, there were 25 AIS patients (7.6% of AIS patients) and 26 ICH patients (34.2% of ICH patients) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic Information: PEG versus No PEG

| No PEG (N=356) | PEG (N=51) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (19-97) | 63 (42-95) | 0.5363 |

| Female, n (%) | 151 (42.4%) | 25 (49.0%) | 0.3733 |

| Black Race | 235 (66.4%) | 40 (78.4%) | 0.1517 |

| Past Medical History | |||

| HTN, n (%) | 270 (76.5%) | 40 (80.0%) | 0.5811 |

| CAD, n (%) | 58 (16.4%) | 9 (17.7%) | 0.8205 |

| DM, n (%) | 114 (32.2%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.2412 |

| HLD, n (%) | 142 (40.5%) | 17 (34.0%) | 0.3826 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 134 (37.6%) | 15 (29.4%) | 0.2539 |

| IV tPA (AIS only), n (%) | 119/304 (39.1%) | 11/25 (44.0%) | 0.6331 |

Past medical history data was self-reported unless otherwise found in patient medical records.

Abbreviations: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), Interquartile range (IQR), hypertension (HTN), coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia (HLD), intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA), acute ischemic stroke (AIS).

Table 2.

Admissions, Discharge, and Outcome Data in AIS Verses ICH Patients

| Admissions Data | AIS (N=25) | ICH (N=26) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission NIHSS (for AIS patients) or GCS (for ICH patients), median score (IQR) | 19 (3-31) | 10 (5-15) | n/a |

| Delay from LSN to ED arrival, median min. (IQR) | 180 (28-791) | 65 (20-956) | 0.0676 |

| Dysarthria at admission, n (%) | 16 (64.0%) | 20 (76.9%) | 0.3113 |

| Impaired LOC at admission, n (%) | 1 (4.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 0.0001 |

| Discharge Data | AIS (N=25) | ICH (N=26) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge disposition | 0.3024 | ||

| Home, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Inpatient Rehabilitation, n (%) | 9 (36.0%) | 7 (26.9%) | |

| Skilled Nursing Facility, n (%) | 8 (32.0%) | 11 (42.3%) | |

| LTAC, n (%) | 3 (12.0%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| Hospice, n (%) | 1 (4.0%) | 2 (7.7%) | |

| Expired, n (%) | 3 (12.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| LOS, median days (IQR) | 21 (6-45) | 21 (7-86) | 0.9249 |

| Discharge NIHSS, median score (IQR) | 19 (5-42) | 17 (5-32) | 0.8713 |

| Discharge mRS, median score (IQR) | 5 (3-6) | 5 (4-5) | 0.3931 |

| Outcome Data | AIS (N=25) | ICH (N=26) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological Deterioration, n (%) | 21 (84.0%) | 6 (75%) | 0.3198 |

| Tracheostomy placed, n (%) | 3 (12.0%) | 11 (42.3%) | 0.0137 |

| Bacteremia, n (%) | 8 (32.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 0.1494 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 11 (44.0%) | 14 (56%) | 0.1572 |

All laboratory and clinical information is taken from chart or patient reported.

Abbreviations: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), National Institute of Health Stroke Score (NIHSS), inter-quartile range (IQR), last seen normal (LSN), emergency department (ED), loss of consciousness (LOC), long-term acute care (LTAC), length of stay (LOS), modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

Risk Prediction Model –AIS

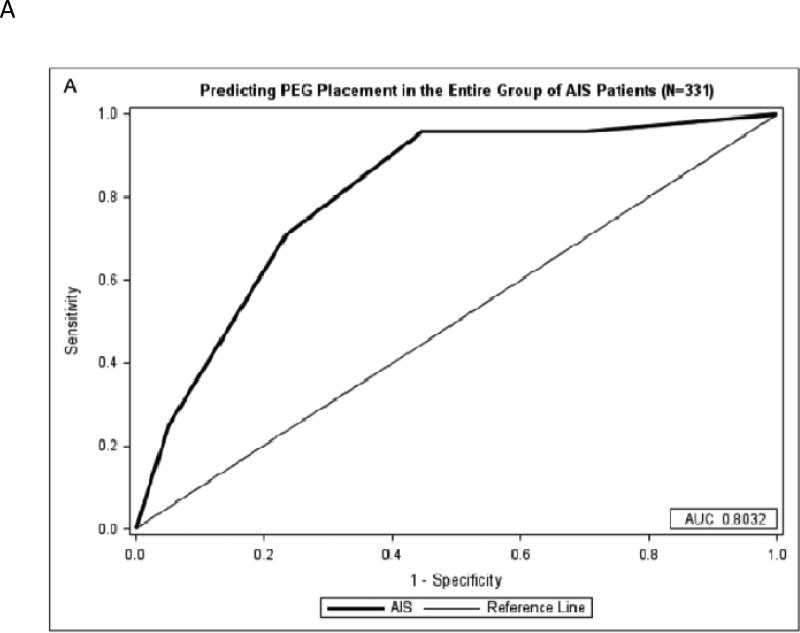

The AIS PEG score was developed with 1 point being awarded for each of the following: age ≥80 years, 24-hour NIHSS score 8-14 (with an extra point for 24-hour NIHSS score >14), 1 point for black race, and 1 point for the infarct location involving cortex with a maximum of 5 points. Severity of dysphagia documented by speech therapy, dichotomized as nil per os (NPO) versus liquid or solid foods permissible, was not predictive of PEG placement, and therefore not included in the model (p=0.252). We found that for the entire cohort, the odds of patients with PEG score ≥3 getting a PEG as an inpatient were 15 times higher than those with PEG score <3 (OR 15.68, 95% CI 4.55-54.01), and a score of ≥3 points is 91.7% sensitive and 62.8% specific for undergoing PEG placement during hospitalization for AIS patients with stroke (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A: Predicting PEG Placement in AIS Patients

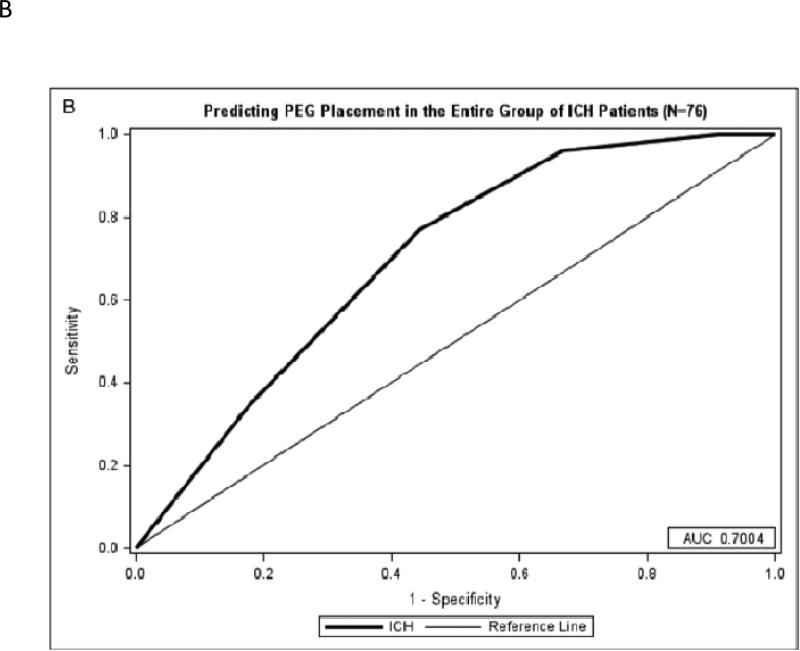

Figure 1B: Predicting PEG Placement in ICH Patients

A) A maximum of 5 points can be achieved from the AIS-PEG model. An area under the curve of 0.8032 shows the model is very predictive of PEG tube placement. B) A maximum of 5 points can be achieved from the ICH-PEG model. An area under the curve of 0.7004 for the model shows a moderate predictive value of PEG tube placement.

Abbreviations: Acute ischemic stroke (AIS), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), receiver operator characteristic (ROC)

Risk Prediction Model – ICH

The ICH PEG score was developed with 1 point being awarded for each of the following: black race, 24-hour NIHSS score 8-14 (with an extra point for 24-hour NIHSS score >14), midline shift on initial head computed tomography scan (HCT; >3mm), and edema on follow up HCT with a maximum of 5 points. Again, severity of dysphagia did not reach statistical significance for predicting PEG placement (p=0.523). With this risk prediction model, the odds of ICH patients with PEG score of ≥3 undergoing PEG placement as an inpatient were nearly 12 times higher than those with PEG score <3 (OR 12.49, 95% CI 1.54-101.29), and a score of ≥3 points is 96.2% sensitive and 33.3% specific for having a PEG tube placed (Figure 1).

Discussion

Severe strokes, baseline dysarthria, and impaired LOC were associated with increased PEG tube placement, which is consistent in the literature.2, 6, 7 Despite this association, dysarthria and LOC were not included in the models due to nonsignificance.

The AIS risk prediction model was found to be more prognostic of future PEG placement than the ICH risk model. The PEG score could be used to demonstrate need for surgical feeding tube insertion by the day after admission, potentially minimizing length of stay.

Our study is limited by its small sample size involving only one academic center, making our results difficult to generalize to larger populations, and by the retrospective nature of this study. We mitigated these limitations by extensively documenting admission physical exam data, allowing us to create an effective model to predict PEG placement very early during hospitalization. The study is further limited by the method of classifying the severity of dysphagia, as it does not utilize a validated dysphagia scoring system.

In summary, our data presents a new tool for estimating who will undergo PEG placement. With the expedited placement of a PEG, enteral nutrition can be initiated and the risks of malnutrition, prolonged length of stay, and mortality could be minimized. In order to appreciate the full implications of such a scoring system, we recommend validating this risk prediction model prospectively and with other stroke registries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to fund Clinical Research Fellow Perry Dubin. The project described was supported by Award Numbers 5 T32 HS013852-10 from The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 3 P60 MD000502-08S1 from The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by award 13PRE13830003 from the American Heart Association. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ, AHA or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures

There are no disclosures for this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dennis MS, Lewis SC, Warlow C. Effect of timing and method of enteral tube feeding for dysphagic stroke patients (food): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:764–772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alshekhlee A, Ranawat N, Syed TU, Conway D, Ahmad SA, Zaidat OO. National institutes of health stroke scale assists in predicting the need for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in acute ischemic stroke. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2010;19:347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann G, Hankey GJ, Cameron D. Swallowing function after stroke: Prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1999;30:744–748. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figueiredo FA, da Costa MC, Pelosi AD, Martins RN, Machado L, Francioni E. Predicting outcomes and complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:333–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malmgren A, Hede GW, Karlstrom B, Cederholm T, Lundquist P, Wiren M, et al. Indications for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and survival in old adults. Food & nutrition research. 2011:55. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Langmore S, Goddeau RP, Jr., Alhazzani A, Selim M, Caplan LR, et al. Predictors of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in patients with severe dysphagia from an acute-subacute hemispheric infarction. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2012;21:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okubo PC, Fabio SR, Domenis DR, Takayanagui OM. Using the national institute of health stroke scale to predict dysphagia in acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:501–507. doi: 10.1159/000336240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.