Mucormycosis is an opportunistic infection caused by fungi of the order Mucorales, environmental nonseptate molds widely distributed in soil, plants, and decaying materials [1]. Mucormycosis can be divided into the following categories on the basis of the site of infection: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, and disseminated [2-4]. The most common clinical presentation is rhinocerebral disease, followed by pulmonary infection.

Medically important Mucorales are Lichtheimia, Absidia, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Rhizopus, Cunninghamella, and Syncephalastrum. Identification of Mucorales is primarily based on standard mycological methods. However, culture-based identification is often difficult and time-consuming. Conventional phenotypic methods usually identify isolates only to the genus level, and sometimes only as Mucorales. In recent years, internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing has been applied to fungi and is considered a reliable method for the accurate identification of most pathogenic Mucorales to the species level [5]. However, a few species have high ITS sequence homology, making their differentiation difficult.

Here we report a case of fatal pulmonary mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus microsporus in an 83-yr-old man newly diagnosed with diabetes. The isolate was identified by a combination of phenotypic methods and genetic sequencing of the ITS and D1/D2 domains.

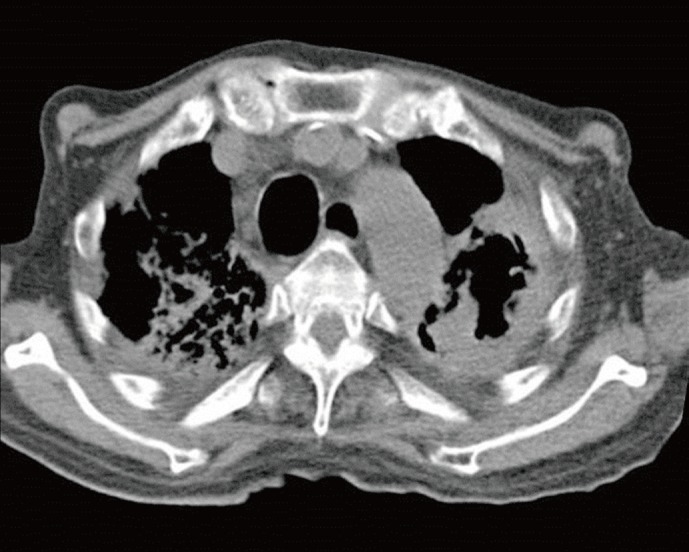

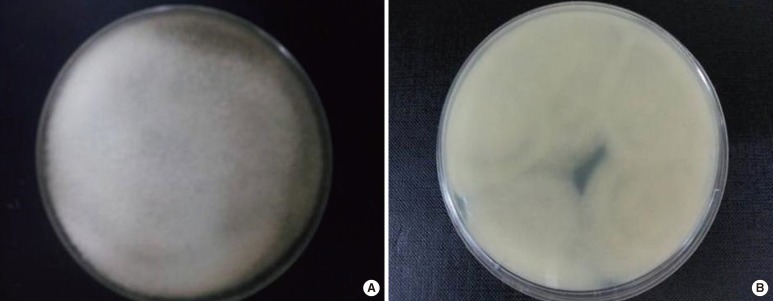

An 83-yr-old man was referred to a tertiary hospital because of the increased sputum with dyspnea. He had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis in his 20s. Fasting blood glucose was 210 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c was 8.4% on initial laboratory tests. He was newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. His chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed large cavitary lesions in the upper lungs (Fig. 1). Acid-fast staining and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid culture yielded negative results. On the fifth day of hospitalization, the serum Aspergillus galactomannan index value was slightly increased at 0.87 (threshold, 0.5). With a diagnosis of suspected pulmonary aspergillosis, itraconazole therapy (400 mg bid) was initiated. Fungus culture of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was performed on Sabouraud dextrose agar at room temperature. After 3 days of incubation, white, aerial, cotton candy-like colonies appeared and quickly covered the agar surface (Fig. 2). These colonies turned pale brownish gray and light yellow reverse with time. Sputum culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar revealed the same colonies. Microscopic examination showed broad, unseptated hyphae. Sporangiophores were unbranched and arose singly or in groups from above rhizoids. Sporangia were spherical, brown, and filled with sporangiospores (Fig. 3). The organism was provisionally identified as a Rhizopus species on the basis of colony morphology and microscopic features. Antifungal therapy was switched to intravenous amphotericin B.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography of chest showed traction bronchiectasis, fibrosis, and large cavitary lesion in both upper lobes.

Fig. 2.

Culture of sputum incubated at room temperature on Sabouraud dextrose agar for 3 days. (A) The front side shows whitish cottony aerial colonies. (B) The reverse side shows light yellow colonies.

Fig. 3.

Rhizopus microsporus. The stolons with rhizoids were shown right under unbranched brown sporangiophores about 600 µm high having columellate, and brown sporangia filled with sporangiospores (lactophenol cotton blue stain, ×400).

For further identification, the ITS region (including the 5.8S ribosomal DNA gene) of the 28S ribosomal DNA was sequenced with primer ITS1: 5'-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3' and primer ITS4: 5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3' [6]. The isolate was identified as either Rhizopus microsporus or R. azygosporus by GenBank's Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (accession numbers GQ328854.1 and DQ119008.1) with 99.5% homology to both species. Sequencing of the D1/D2 regions yielded the same result. The isolate grew at 37℃, 40℃, and 45℃, but did not grow at 50℃, and its sporangiospores were striated. On the basis of these phenotypic characteristics, the isolate was finally identified as R. microsporus. The patient died of respiratory insufficiency on the 35th day after admission.

Mucormycosis is an emerging infectious disease and represents the second leading cause of invasive mold infection, following aspergillosis [7]. It is reported mainly in patients with hematologic malignancy, organ transplantation, immunosuppressive therapy, and diabetes [2]. Diabetes is the most common underlying condition, and Roden et al. [8] reported that 36% of patients with mucormycosis had diabetes at the time of infection, and mucormycosis led to the diagnosis of diabetes in 16% of these patients. In this case, the patient was newly diagnosed with diabetes at admission. Ketoacidosis and uncontrolled hyperglycemia may be related to mucormycosis acquisition in patients with diabetes [9].

Pulmonary mucormycosis is a rapidly progressive disease. The overall mortality rate is above 70% [8]. The clinical findings and chest imaging features are not specific, and it is often difficult to differentiate between aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Unfortunately, the therapeutic regimens for these 2 diseases are different. Azole, used for invasive aspergillosis, has limited activity for mucormycosis [7, 10]. Moreover, mucormycosis has been recently reported in patients receiving voriconazole for prophylaxis or for treatment of invasive aspergillosis [11]. A delay in administering the appropriate therapy often leads to poor outcomes. Thus, rapid diagnosis is very important for optimal therapeutic management.

Fungus culture is the primary method for the diagnosis of mucormycosis. Mucorales are easily recognized by their grayish, fluffy colonies that rapidly fill the culture media. The differentiation of the various genera is based on the presence and location of rhizoids, the branching nature of the sporangiophores, the shape of the columella, the size and shape of the sporangia, and the maximum growth temperature. However, the identification of Mucorales species based on morphological features alone can be difficult. It is time-consuming and requires experience in the recognition of microscopic differences. Kontoyiannis et al. [7] reported that approximately 21% of Rhizopus species were erroneously identified by morphology, compared with ITS sequencing.

To overcome the limitations of morphology-based identification, molecular identification is applied. Ribosomal DNA sequences including the V9 region of the 18S ribosomal RNA, the D1/D2 domains of the 28S ribosomal DNA, and the ITS region are used for fungal identification [6]. The ITS region, including 5.8S ribosomal DNA, is recommended as the standard choice for identification of human pathogenic Mucorales to the species level [12]. The ITS sequences of most Mucorales are highly variable and species-specific. R. oryzae and R. microsporus show only 70% similarity between their ITS sequences, allowing for clear differentiation. Most Mucor spp. possess 79-96% sequence similarity, allowing for good species identification [5].

Although ITS sequencing is reliable for identification of Mucorales species, a few closely related species have nearly 100% identical ITS regions. The sequences of R. microsporus are nearly identical to those of R. azygosporus [5]. The sequences of M. circinelloides demonstrate a 99-100% match with those of M. rouxii or Rhizomucor variabilis var. regularior [13]. For differentiation of these species, sequencing of the ITS region alone is inadequate. Alternative DNA targets such as the D1/D2 domains of the 28S ribosomal DNA may be needed for differentiation.

We present a case of fulminating pulmonary mucormycosis by R. microsporus in a patient with diabetes mellitus. We emphasize the importance of rapid and accurate identification of the pathogen by both morphology and molecular techniques for appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by a Gachon University Gil Medical Center Research Grant 2012.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Garcia-Hermoso D, Dannaoui E, Lortholary O, Dromer F. Agents of systemic and subcutaneous mucormycosis and entomophthoromycosis. In: Versalovic J, Carroll KC, Funke G, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Warnock DW, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 10th ed. Washington, DC: ASM press; 2011. pp. 1880–1901. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 1):S16–S22. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilos G, Samonis G, Kontoyiannis DP. Pulmonary mucormycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:693–702. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ. Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:236–301. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.236-301.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz P, Bretagne S, Gantier JC, Garcia-Hermoso D, Lortholary O, Dromer F, et al. Molecular identification of zygomycetes from culture and experimentally infected tissues. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:340–349. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.340-349.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park Y. Sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA in the genus Rhizopus. Mycobiology. 2005;33:109–112. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2005.33.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kontoyiannis DP, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Healy M, Perego C, et al. Zygomycosis in a tertiary-care cancer center in the era of Aspergillus-active antifungal therapy: a case-control observational study of 27 recent cases. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1350–1360. doi: 10.1086/428780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg J, Sujatha S, Garg A, Parija SC. Nosocomial cutaneous zygomycosis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e508–e510. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Mol P, Meis JF. Disseminated Rhizopus microsporus infection in a patient on oral corticosteroid treatment: a case report. Neth J Med. 2009;67:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigouroux S, Morin O, Moreau P, Méchinaud F, Morineau N, Mahé B, et al. Zygomycosis after prolonged use of voriconazole in immunocompromised patients with hematologic disease: attention required. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:e35–e37. doi: 10.1086/427752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balajee SA, Borman AM, Brandt ME, Cano J, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dannaoui E, et al. Sequence-based identification of aspergillus, fusarium, and mucorales species in the clinical mycology laboratory: where are we and where should we go from here? J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:877–884. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01685-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez E, Sutton DA, Cano J, Fothergill AW, Stchigel A, Rinaldi MG, et al. Spectrum of zygomycete species identified in clinically significant specimens in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1650–1656. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00036-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]