Abstract

Biliary candidiasis is increasing in the hospitalized immunosuppressed individuals. Placement of biliary stents in the cancer patients with obstructive jaundice has been found to be an important factor associated with infectious complications. Positive fungal cultures from bile should not be ignored as mere contamination but should be considered when prescribing treatment for the immunosuppressed with recurrent cholangitis or receiving long-term antibiotic therapy. Here,we report a case of cholangiocarcinoma with cholangitis where Candida tropicalis was the sole pathogen isolated from bile. This is probably the first case of its kind to be reported from Manipal, Karnataka, South India.

Keywords: Candida tropicalis, Biliary candidiasis, Cholangiocarcinoma, Cholangitis, Biliary stents

1. Introduction

Infections with Candida species are of increasing frequency and significance in the hospitalized patient, especially in those with impaired immune systems [1,2]. Many factors have contributed to this rise, including more aggressive use of chemotherapy and immunosuppressive agents, corticosteroids, parenteral hyperalimentation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics [1,3]. Clinical isolation of Candida may represent colonization or infection [7]. Fungal biliary aspirates are frequently positive in patients who have stents and have been on antibiotics [8].

With the increasing use of therapeutic hepatobiliary procedures in patients with cancer, the prevalence of complications, including infections, has increased. The procedures of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) and endoscopic biliary stents (endoprostheses) for decompression of malignant obstructive biliary disease have been useful as alternatives to surgical intervention [1,2].

Infection was not reported as a significant complication of these procedures in a number of early studies. Recent literature, however, has emphasized the risk of infectious complications related to these procedures. The role of contributing factors in patients with cancer has been observed to have a high infection rate as stressed by other authors [1,2].

Surgical decompression has been reported to be associated with mortality rates of 20–40% in patients with primary biliary malignant lesions [1,3] and of 59% in patients with extensive metastasis [4]. PTBD and the placement of an endoprosthesis have been used in palliative therapy for obstructive biliary disease in patients with unresectable malignancies, for preoperative biliary decompression, and for management of biliary sepsis. Several authors have reported a reduction in postoperative mortality and morbidity with use of preoperative PTBD [2,5].

Though Candida albicans is the commonest species isolated followed by C.glabrata, it should be kept in mind that Candida tropicalis is also a possible emerging Candidal species and its pathogenic role in biliary Candidiasis needs to be further investigated especially in the immunocompromised patients with cholangitis. C. tropicalis has been identified as the most prevalent pathogenic yeast species of the Candida non- albicans group. Infections due to C.tropicalis have dramatically increased on a global scale thus proclaiming this organism to be an emerging pathogenic yeast[6].

2. Case report

A 56 year old male patient was referred to the surgery unit of Kasturba Hospital Manipal in the month of October 2011 with the complaints of jaundice, loss of appetite and weight and intermittent fever for the past 3 months. He was diagnosed to have obstructive jaundice due to an inoperable cholangiocarcinoma by Computerized Tomography (CT) which showed a lesion suspicious of cholangiocarcinoma in the distal bile duct with ascites. On clinical examination following admission on day 0, the patient was found to be nourished and of moderate built, febrile and deeply jaundiced. Examination per abdomen revealed hepatomegaly. Bowel sounds were normal.

Laboratory investigations & Results: Routine laboratory investigations performed on day 0 of hospital admission revealed leukocytosis (19.6×103/μl) and differential count revealed 76% neutrophils with a left shift with toxic changes. The liver function tests showed a markedly elevated direct bilirubin (20 mg/dl) and alkaline phosphatase (443U/L) with moderate elevation of aminotransferases (AST 114 IU/L, ALT 66 IU/L).

In view of obstructive jaundice, leukocytosis and fever, the diagnosis of cholangitis secondary to biliary obstruction was made and the patient was empirically started on cefoperazone-sulbactam (1.5 g Q8H) and tinidazole (800 mg once daily) intravenously after sending blood for culture and sensitivilty on day 0.

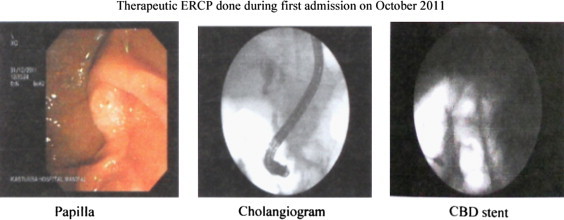

Ultrasonography done on day 3 revealed the same findings as the CT done earlier outside Kasturba hospital i.e. stricture of the distal common bile duct with ascites. Considering the patient's poor general condition, cholangitis and radiological appearance of an inoperable cholangiocarcinoma, it was decided to stent the common bile duct via Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio Pancreatograhy (ERCP) to drain the infected bile and palliate the obstructive jaundice. ERCP and stenting was done on day 4 after checking the coagulation profile (which was found to be normal) (Fig. 1). During the procedure a sample of bile was obtained for culture and sensitivity.

Fig. 1.

Microbiological investigations: Both the blood and bile culture and sensitivity reports revealed the growth of ESBL producing Klebsiella pneumoniae which was sensitive to amikacin, cotrimoxazole, netilmycin, cefoperazone–sulbactam, meropenem and resistant to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, ampicillin, cefazolin, cefotaxime, cefuroxime and ciprofloxacin. Hence cefoperazone–sulbactam was continued and given for a total period of 14 days. Serology for HBsAg, HCV spot test were non-reactive and HIV rapid test and ELISA were also negative. In the meantime, the general condition of the patient improved, he was afebrile and his jaundice decreased clinically and biochemically. His WBC counts dropped to normal and he was discharged in November 2011 upon completion of the antibiotic course and advised for a follow up check up after one month.

The patient returned to the emergency department in the last week of January 2012 and was readmitted with the complaints of malaise since 2 days and had stopped eating food. Examination revealed fever and mild icterus. Investigations performed on day 1 of readmission revealed the following results: peripheral smear report revealed presence of RBCs which were normocytic and normochromic, blood smear report revealed a high total WBC count of 23.6×103/μl with a left shift with toxic granules, a differential count of 80% and platelet count appeared low normal. Liver function test results revealed elevated direct bilirubin (4 mg/dl) and elevated liver enzymes namely aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP ) being 52 IU/L, 40 IU/L and 200 U/L respectively. Prothrobin time showed an INR of 3.Ultrasonography done on day 1 of readmission revealed moderate dilatation of intra and extra hepatic bile ducts with a mass in the region of distal common bile duct.

He developed hypotension on day 2 of readmission, was given ionotropic support and then shifted to the ICU. In view of leukocytosis, biliary dilatation radiologically and moderately elevated direct bilirubin, a diagnosis of cholangitis secondary to obstructive jaundice was made again and the patient was again started on cefoperazone–sulbactam and tinidazole parenterally, after obtaining blood for culture and sensitivity. Blood culture report was sterile.

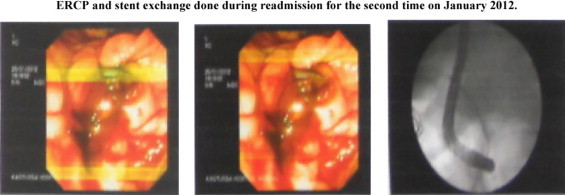

Due to prolonged prothrombin time, the patient was given vitamin K injections (10 mg) daily for 3 days. He received fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and his low platelet count was treated with platelet rich plasma (PRP).Once the patient became hemodynamically stable and his bleeding parameters were normal, he underwent an ERCP and stent exchange on day 4 of readmission (Fig. 2). During this process his bile was sampled for culture and sensitivity which grew C. tropicalis as the sole pathogen which was identified and confirmed by VITEK 2C (Biomerieux) Identification system.

Fig. 2.

Following stent exchange, the patient again became hemodynamically unstable, developed anuria and hypotension, did not respond to supportive measures and succumbed to his ailments and died on day 6 of readmission.

3. Discussion

Infectious complications are common in patients with cancer who are undergoing biliary drainage procedure. In most of the cases of cholangitis due to cholangiocarcinoma, the common pathogens that are cultured from bile are the aerobic Gram negative bacilli. Fungal infections of the hepatobiliary system are uncommon and the various fungi reported to infect the biliary tree include C. albicans, Blastomyces dermatitidis and Cryptococcus neoformans [10]. But of late, C. tropicalis is also being isolated from biliary aspirates of patients with cholangitis who have some form of malignancy or have undergone some surgical procedure involving the biliary tract as seen in this case. Our patient's bile sample grew C. tropicalis as the sole pathogen and this is perhaps the first case of C.tropicalis being isolated from bile of a patient with cholangitis due to cholangiocarcinoma, from this part of coastal Karnataka, Manipal, India.

The pathogenesis is not certain, the reported postulations are direct invasion of the common bile duct from the duodenum or systemic Candida sepsis could establish microabscess in liver parenchyma following movement of candida organisms into the bilary tree [10]. Another vital question to consider is the route by which Candida species reach the biliary tract: is it by infection or by colonization?There are 3 possible pathways: (a) ascending (from the midgut or hindgut), (b) hematogenous (fungemia and sepsis) and (c) via instrumentation (ERCP/stenting) [9].In patients with preexisting damage of the biliary tract, eg, CBD stenosis (benign or malignant), fungal species have an invasion point[9].

From our experience of the few cases where the biliary aspirates of the patients with cholangitis had a pure growth of C. tropicalis, we feel that colonization may have played an important role in biliary candidiasis apart from other contributing factors like malignancy and existing biliary stents in those patients. To conclude, Candida species can frequently be isolated from the biliary aspirates. Positive fungal cultures of bile samples should not be ignored as just contamination artifacts, but it has to be taken into account when designing anti-infectious treatment of recurrent cholangitis or even more cholangiosepsis. Physicians should screen for biliary-tract candidiasis during endoscopic examination, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed or recipients of long-term antibiotic therapy. During endoscopic examination, Candida conglomerates can be assumed when long tubular, filamentous structures (mycelia) with several branches and a gray-to-dark color can be extracted from the biliary tract [9].

Conflict of interest statement

There are none.

Acknowledgments

There are none.

References

- 1.Kozarek R.A., Sanowski R.A. Nonsurgical management of extrahepatic obstructive jaundice. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1982;96:743–745. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khardori N., Wong E., Carrasco C.H., Wallace S., Patt Y., Bodey G.P. Infections associated with biliary drainage procedures in patients with Cancer. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 1991;13(4):587–591. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.587. July–August. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarr M.G., Cameron J.L. Surgical management of unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. Surgery. 1982;91:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feduska N.J., Dent T.L., Lindemauer S.M. Results of palliative operations for carcinoma of the pancreas. Archives of Surgery. 1971;103:330. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350080246039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakayama T., Ikeda A., Okuda K. Percutaneous transhepatic drainage of the biliary tract:techniques and results in 104 cases. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:554–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothavade Rajendra J., Kura M.M., Valand Arvind G, Panthaki M.H. Candida tropicalis: its prevalence, pathogenicity and increasing resistance to fluconazole. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010;59:873–880. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.013227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris B., Sands L., Shiraki Masanori, Brown B., Ryczak Mary. Gallbladder and biliary tract candidiasis: Nine cases and review. Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 1990;12:483–489. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Story Brian, Gluck Michael. Obstructing fungal cholangitis complicating metal biliary stent placement in pancreatic cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(24):3083–3086. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz Philipp. Prevalence, associations, and trends of biliary-tract candidiasis:a prospective observational study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2009;70(3):480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta N.M., Chaudhary A., Talwar P. Candidial obstruction of the common bile duct. British Journal of Surgery. 1985;72:13. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]