Abstract

Introduction

Favus of the scalp or tinea capitis favosa is a chronic dermatophyte infection of the scalp. In almost cases, favus is caused by Trichophyton schoenleinii, anthropophilic dermatophyte. It is characterized by the presence of scutula and severe alopecia. Besides the classic clinical type of tinea capitis favosa, there are many variant of clinical form which may persist undiagnosed for many years. In this work, we report an atypical form of favus to Trichophyton schoenleinii which was misdiagnosed as tinea amiantacea.

Case-report

An 11-year old girl came to the outpatient department of dermatology (day 0) with history of tinea amiantacea treated unsuccessfully with keratolytic shampoo (day – 730). She presented a diffuse scaling of the scalp with thick scaly patches and without scutula or alopecia. A diagnosis of tinea favosa by T. schoenleinii was made by mycological examination. She was treated with griseofulvin and ketoconazole in the form of foaming gel for twelve weeks. Despite treatment, clinical evolution was marked by appearance of permanent alopecia patches. The follow-up mycological examination was negative.

Conclusion

Because of ultimate evolution of favus into alopecia, we emphasize the importance of mycological examination in case of diffuse scaling.

Keywords: Tinea favosa, Favus, Trichophyton schoenleinii, Tinea amiantacea, Tunisia

1. Introduction

Tinea favosa is a chronic dermatophyte infection of the scalp and, less commonly, of the glabrous skin and nails. In most cases, favus is due to Trichophyton schoenleinii which is an anthropophilic dermatophyte. Favus of the scalp is characterized by the presence of scutula and severe alopecia. Besides this classic clinical form, there are many atypical clinical forms which can persist for years before being diagnosed [1–4].

Tinea capitis favosa has been frequent in Tunisia presenting 23% of tinea cases in 1950 [5]. Thanks to the anti-favus campaigns and the improvement in living conditions and hygiene, favus is becoming exceptional; it is only presenting 0.24% to 1.6% of total cases [6,7]. This infection is so rare that tinea favosa can be misdiagnosed. By this atypical observation, we should recall the tinea favosa in order to an early and adequate management.

2. Case

An 11-year old girl came to the outpatient department of dermatology (day 0) with history of tinea amiantacea treated unsuccessfully with keratolytic shampoo (day – 730). Physical examination revealed a diffuse scaling of the scalp with thick hairless patches containing hairs which are broken in some cm of their emergence, without scutula. No other dermatological or ungueal abnormality was observed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tinea favosa with a diffuse scaling of the scalp.

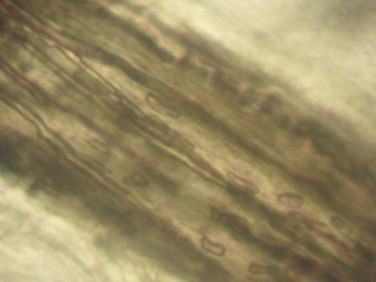

Scales and altered hairs were collected. The direct microscopic examination of the hairs in 20% potassium hydroxide revealed an endothrix pilar invasion with the presence of septate hyaline hyphae (Fig. 2). The culture on Sabouraud glucose agar at 27 °C yielded in twenty days white limited colonies producing ramifications that submerged into agar (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination revealed the presence of multiple branched hyphae known as favic chandeliers, terminal dilation of hyphae giving a nail head shape known as favic nails and some chlamydoconidia (Fig. 4a and b).

Fig. 2.

Direct microscopic examination showing endothrix hair invasion with septate hyaline hyphae (20% Potassium hydroxide, 400×).

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic examination of Trichophyton schoenleinii on Sabouraud medium.

Fig. 4.

(a and b). Microscopic examination of Trichophyton schoenleinii showing characteristic favic chandelier and favic nail (lactophenol cotton blue 100×).

Based on the clinical and mycological data, the diagnosis of tinea favosa by T. schoenleinii was made. The patient was treated with 20 mg/kg/d of oral grisofulvin and ketoconazol in the form of foaming gel (once a day) during twelve weeks. Despite the regular intake of the treatment, the clinical evolution was marked by the appearance of grey hair and permanent alopecia patches (Fig. 5). The follow-up mycological examination was twice negative (two months (day +60) and three months (day +90) after the end of the treatment). The epidemiologic survey did not reveal the origin of the contamination.

Fig. 5.

Clinical evolution after treatment: gray hair and ultimate alopecia patches.

3. Discussion

Although the favus occurred worldwide, it is at present limited to some endemic regions. It was mainly endemic in the Middle East, Iran, Kashmir, certain North and South African regions, Denmark and some foci in America, especially the USA, Canada, Brazil [2]. Thanks to the improvement in living conditions and hygiene and the introduction of grisofulvin in 1958, favus was eradicated or became very rare in the majority of these regions especially Tunisia. It is now limited to some endemic regions like China, Iran and Nigeria [2,8–11].

Favus could occur during childhood or adolescence and persists to adulthood in case of absence of treatment [2,12]. Contrary to the other types of tinea, tinea favosa does not disappear until puberty but persists as long as there is hair. Its evolution is slow [1,2].

T. schoenleinii which is the isolated specie in our patient is responsible for the majority of tinea favosa cases [1–4,9,13,14]. Other species could rarely determine this tinea. It is the anthropophilic species, Trichophyton violaceum, zoophilic species, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Microsporum canis and geophilic species, Microsporum gypseum [1,2].

The classic favus lesion is the scutula, a yellowish cup-shaped crust of 0.5 to 1.5 cm of diameter on the scalp from where come out dull grey hair. The fusion of many scutula determines the crust favic which is straw-colored and crisp. It is the origin of the name favosa which means honeycomb. The scalp is characterized by an unpleasant “mousy” odor. The parasitized hair will fall down causing a final alopecia. This typical form which associates scutula, dull grey hair and alopecia patches is met in 95% of the cases [1,2,15]. Besides this clinically typical form, there are atypical tinea favosa which makes about 5% of the cases. In presence of scaly patches without alopecia, favus could be similar to seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis or tinea amiantacea [2,3,14]. This was the case of our patient in whom favus was misdiagnosed as a tinea amiantacea. This confusion was also reported by other authors [14]. Tinea amiantacea is characterized by scaling of the scalp. The scaling is white yellowish, thick, “asbestos-like” and binds down tufts of hair [1,16]. It may be difficult clinically to distinguish from atypical favus of the scalp without doing mycological examination.

Regardless of the clinical form, lesions evolve in all cases into ultimate scarring alopecia, which imposes an early diagnostic and therapeutic management. Indeed, if treated at an early stage of evolution, tinea favosa will cured without sequelae. However, if the treatment is late established it will not prevent the ultimate scarring alopecia, which was the case of our patient [1,2,4]. It is then important to diagnose tinea favosa at an early stage. The diagnostic lies on the mycological examination of the parasitized hair and scutula. The sample should be made easier by the Wood's light examination which reveals a green fluorescence [1,2,4]. The direct examination reveals a strict endothrix pilar invasion with an entanglement of the mycelial filaments at the scutula [1–4,9,13,14].

In Sabouraud medium, T. schoenleinii has been growing slowly between 2 to 4 weeks giving two macroscopic aspects of colonies: waxy colonies or limited white colonies with ramifications that emerging in agar. This last aspect was noticed in our case [1–4,9,13,14].

The treatment of tinea favosa lies on the association of an oral and topical treatment. The local treatment consists in cutting of hair around the alopecia patches and applying once or twice a day of antifungal imidazol (shampoo, foam gel, lotion and spray). The systemic treatment is mainly based on a 15 to 20 mg/kg/d griseofulvin per os during 10 to 12 weeks [1–4,14]. The resistance of the T. schoenleinii to the griseofluvin has been described. The multiple-layered, thick cell wall of the fungi may act as a barrier impermeable to griseofulvin [17]. In this case, other antifungal treatment could be used like the terbinafine and itraconazole. T. schoenleinii is transmitted from one person to another by the use of common combs or hats [1,2,13]. It is then necessary to look for an infesting family or school environment. In our case, the survey has remained negative.

Conflict of interest

There is none.

Acknowledgments

There is none.

References

- 1.Chabasse D, Guiguen CP, Contet-Audonneau N. Mycologie Médicale. Masson; Paris: 1999. Mycoses autochtones et cosmopolites, diagnostic et traitement. p. 127–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s11046-010-9312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khaled A., Ben Mbarek L., Kharfi M., Zeglaoui F., Bouratbine A., Fazaa B. Tinea capitis favosa due to Trichophyton schoenleinii. Acta Dermatovenerologica Alpina, Panonica, et Adriatica. 2007;16:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaraa I, Hawilo A, Aounallah A, Trojjet S, El Euch D, Mokni M, et al. Inflammatory Tinea capitis: a 12-year study and a review of the literature. Mycoses July 3, 2012 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Coutelen J., Cochet G., Biguet J., Mullet S., Doby-Dubois M., Deblock S. Contribution à la connaissance épidémiologique et mycologique des teignes infantiles en Tunisie. Annales de Parasitologie Humaine Comparee. 1956;31:449–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belhaj S., Jguirim H., Anane S., Kaouech E., Kallel K., Chaker E. Evolution des teignes du cuir chevelu à Microsporum canis et à Trichophyton violaceum à Tunis. Journal of Medical Mycology. 2007;17:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saghrouni F., Bougmiza I., Gheith S., Yaakoub A., Gaïed-Meksi S., Fathallah A. Mycological and epidemiological aspects of tinea capitis in the Sousse region of Tunisia. Annales de Dermatologie et de Venereologie. 2011;138:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng S., Bulmer G.S., Summerbell R.C., De Hoog G.S., Hui Y., Gräser Y. Changes in frequency of agents of tinea capitis in school children from Western China suggest slow migration rates in dermatophytes. Medical Mycology. 2008;46:421–427. doi: 10.1080/13693780701883730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahromi S.B., Khaksar A.A. Aetiological agents of tinea capitis in Tehran (Iran) Mycoses. 2006;49:65–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nweze E.I. Etiology of dermatophytoses amongst children in northeastern Nigeria. Medical Mycology. 2001;39:181–184. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.2.181.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seebacher C., Bouchara J.P., Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335–352. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta A.K., Summerbell R.C. Tinea capitis. Medical Mycology. 2000;38:255–287. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.4.255.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matte S.M., Lopes J.O., Melo I.S., Costa Beber A.A. A focus of favus due to Trichophyton schoenleinii in Rio Grande do Sul. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 1997;39:1–3. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651997000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velho G.D., Selores M., Amorim I., Lopes V. Tinea capitis by Trichophyton schoenleinii. European Journal of Dermatology : EJD. 2001;11:481–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viguié Vallanet C. Les teignes. Annales de Dermatologie et de Venereologie. 1999;126:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon C.M., Schissel D.J. Pityriasis amiantacea. Cutis. 1999;63:169–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng Y.C. Morphology of griseofulvin-resistant isolates of Mongolian variant Trichophyton schoenleinii. Chinese Medical Journal. 1990;103:489–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]