Abstract

We report here a clinical case of phaeohyphomycosis in an 18-year-old male giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Skin lesions on the giant panda disappeared following 2 months of treatment with ketoconazole. Three months after discontinuing the treatment, there was a clinical and mycological relapse. The disease progression was no longer responsive to ketoconazole. Microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis revealed that the infection was caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides. A 4-month treatment regime with Itraconazole oral solution (700 mg per day) successfully terminated the infection.

Keywords: Cladosporium cladosporioides, Phaeohyphomycosis, Polymerase chain reaction, Itraconazole

1. Introduction

Phaeohyphomycosis is a mycotic infection caused by dematiaceous fungi [1,2]. Cladosporium cladosporioides is one of the most common dematiaceous fungi that inhabits saprophytic and soil environments. Other species of Cladosporium have also been found in both outdoor and indoor atmospheres [3,4]. C. cladosporioides causes infections with various clinical features including infection of the skin [2–5], keratomycosis [6], corneal ulcer [7], brain abscess [8,9], pulmonary ball [9], and dental granuloma [10].

We report here a clinical case of phaeohyphomycosis found in a giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis revealed that the phaeohyphomycosis was caused by C. cladosporioides. The phaeohyphomycosis was successfully treated with the antimycotic Itraconazole.

2. Case report

The giant panda was an 18-year-old male, who lived in a semi-captive and semi-stocking environment at the Giant Panda Protection Research Center. The center is located in Ya'an, a humid, mountainous area in southwest China. A small amount of hair loss was observed at the dorsum nasi of the giant panda and the skin of the dorsum nasi was scratched by its front paws. The dermatic lesion on its dorsum nasi was measured as 12 cm×8 cm (Fig. 1). The skin lesion, which was initially hard, erythematous and displayed edema, later became pruritic. Skin scrapings were examined using a microscope and fungal spores were identified. The identification of these symptoms was defined as day 0.

Fig. 1.

Nose infection of the giant panda as indicated by hair loss, redness and swelling of the skin.

Five days after the symptoms were identified, the giant panda was first treated with antimycotic ketoconazole (600 mg/day orally), and the treatment regimen continued for 2 months. The skin redness disappeared and hair loss was recovered.

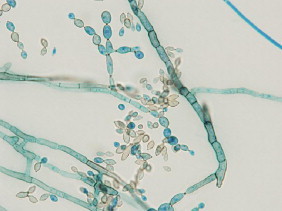

However, the same symptoms recurred 3 months after the ketoconazole treatment stopped. The same treatment was reinitiated but the giant panda was not responsive to the second treatment with ketoconazole. Samples of the secretion, furfurescence, thrix and hair follicles of the dorsum nasi were collected. The samples were cultured on Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) at 25 °C for 2 weeks. Black colonies were observed on the agar and the colony discs were subsequently cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 25 °C. After 48 h, yellowish-green colonies had formed and were approximately 1.0 cm in diameter. After 5 days, the colonies gradually turned black and were about 5 cm in diameter. The fungus grew well on SDA at 25–28 °C, grew poorly at 30 °C, and did not grow at 35 °C. Microscopic observation revealed that the fungus had long conidiophores with ellipsoidal conidia. The conidiophores were non-nodose and had both terminal and lateral ramifications (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

A representative fungal colony from a hair follicle cultured for 14 days.

Fig. 3.

Microscopic image of C. cladosporioides cultured on SDA (magnification=1000×).

PCR was performed to further identify the fungus. Genomic DNA was extracted and amplified using primers targeting internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) and internal transcribed spacer 4 (ITS4). The resulting sequence of 509 nucleotides was subjected to a homology search using the BLAST alignment program of the GenBank database. The sequence was 99% identical to the C. cladosporioides gene, with a highest maximum score of 922 (GenBank accession number: JQ727688.1). The expected E value for the identity was 0.0, indicating that this result was non-random and statistically significant. The fungus was thus identified as C. cladosporioides. Oral itraconazole (700 mg daily) was administered. After 3 months of treatment, the edema disappeared and the infection was completely healed (Fig.4). No reoccurrence was found one year after the recovery.

Fig. 4.

The same giant panda as in Fig. 1, after itraconazole treatment for 3 months.

3. Discussion

Cladosporium species are usually either pathogenic to plants or saprophytic. Occasionally, they have been found in culture as contaminants, but rarely reported as etiological agents of animal infection [11]. The most common and typical lesions of phaeohyphomycosis are localized cutaneous or subcutaneous abscesses, granulomas or cysts. Here we reported a case of phaeohyphomycosis in a giant panda, who had obvious symptoms of hair loss at the dorsum nasi, redness and swelling of the skin.

Several treatments have been proposed for the treatment of C. cladosporioides infection. However, cases are rare in giant pandas so it is difficult to make specific therapeutic recommendations. For systemic or local infections (i.e. infections with dermatic lesions), systemic treatment with a few antifungal agents has been recorded. Some of the antifungal agents, such as amphotericin B, ketoconazole and miconazole, have low success rates and frequent relapses [12]. However, ketoconazole was the only antifungal agent available at that time, so it was initially used to treat the infected giant panda. We observed an apparent clinical and mycological cure, but the infection relapsed 3 months after the final ketoconazole treatment.

After isolation and identification of the infectious fungus as C. cladosporioides, we decided to treat the giant panda with itraconazole oral solution, which showed good clinical and mycological responses. Itraconazole is a broad-spectrum, hydrophilic fatty triazole antifungal drug. It is used to treat certain types of internal and external fungal infections. It selectively inhibits the cytochrome enzymes of fungal cells, causes cell membrane damage and cell death. Liver and kidney functions were measured 7 days after stopping the treatment; all indexes were normal.

In conclusion, we identified and successfully treated a rare infection of C. cladosporioides in a giant panda. We demonstrated that PCR for ITS1 and ITS4 ribosomal DNA typing was useful because it allowed quick and accurate identification of the organism, which facilitated prompt initiation of an appropriate therapy—itraconazole.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Xiaomin Liu for helping identify the fungus, and Dr. Chengdong Wang for suggesting the therapy with Itraconazole oral solution.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This study was supported by Youth Fund of Sichuan Provincial Education Department (12ZB093) and by Captive giant pandas Management Research (SD1118).

Contributor Information

Xiaoping Ma, Email: mxp886@sina.com.cn.

Jiafa Hou, Email: jiafahou@163.com.

Chengdong Wang, Email: 285934012@qq.com.

References

- 1.Sang H., Zheng X.E., Zhou W.Q. A case of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladosporium cladosporioides and its treatment. Mycoses. 2012;55(2):195–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vieira M.R., Milheiro A., Pacheco F.A. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladosporium cladosporioides. Medical Mycology. 2001;39(1):135–137. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.1.135.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annessi G., Cimitan A., Zambruno G., Di Silverio A. Cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladosporium cladosporioides. Mycoses. 1992;35(9–10):243–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1992.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gugnani H.C., Sood N., Singh B., Makkar R. Case report. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis due to Cladosporium cladosporioides. Mycoses. 2000;43(1–2):85–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2000.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereiro M., Jr., Jo-Chu J., Toribio J. Phaeohyphomycotic cyst due to Cladosporium cladosporioides. Dermatology. 1998;197(1):90–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew F.L., Subrayan V., Chong P.P., Goh M.C., Ng K.P. Cladosporium cladosporioides keratomycosis: a case report. Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;53(6):657–659. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polack F.M., Siverio C., Bresky R.H. Corneal chromomycosis: double infection by Phialophora verrucosa (Medlar) and Cladosporium cladosporioides (Frescenius) Annals of Ophthalmology. 1976;8(2):139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarcioglu A.S., Yucel A., de Hoog G.S. Case report. Isolation of Cladosporium cladosporioides from cerebrospinal fluid. Mycoses. 2002;45(11–12):500–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2002.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon-Chung K.J., Schwartz I.S., Rybak B.J. A pulmonary fungus ball produced by Cladosporium cladosporioides. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1975;64(4):564–568. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/64.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepe R.R., Bertolotto C. The first isolation of Cladosporium cladosporioides (Fres.) de Vries from dental granulomas. Minerva Stomatologica. 1991;40(12):781–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Hoog G.S., Gueho E., Masclaux F. Nutritional physiology and taxonomy of human-pathogenic Cladosporium-Xylohypha species. Journal of Medical and Veterinary Mycology. 1995;33(5):339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharkey P.K., Graybill J.R., Rinaldi M.G. Itraconazole treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990;23(3 Part 2):577–586. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70259-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]