Abstract

Human pythiosis is an emerging disease caused by Pythium insidiosum, a fungus-like aquatic organism. Clinical presentations can be classified into four types: (i) cutaneous/subcutaneous, (ii) ocular, (iii) vascular, and (iv) disseminated pythiosis. Serological tests such as immunodiffusion and immunochromotographic test are useful to make rapid diagnosis in cutaneous and vascular pythiosis. We report a case of 35 year-old male with vascular pythiosis of both legs, diagnosed by serology and molecular techniques.

Keywords: Vascular pythiosis, Thalassemia, Bilateral leg ulcers

1. Introduction

Human pythiosis is a rare life-threatening disease caused by Pythium insidiosum, a fungus-like organism that belongs to the Kingdom Straminiphila [1]. Infected patients were mostly reported from Thailand and usually had an agricultural background and history of exposure to swampy areas without wearing appropriate protections [2]. Four forms of clinical presentations are documented, cutaneous/subcutaneous, ocular, vascular, and disseminated pythiosis. The majority of the reported patients with vascular pythiosis have unilateral limb involvement [2]. We, herein, report a case of 35 year-old male with bilateral leg ulcers which P. insidiosum has been isolated from both cutaneous and vascular sites.

2. Case

A 35 year-old Thai man with Hemoglobin H/Constant Spring (Hb H/CS) disease was admitted to Siriraj Hospital (day 0) due to low grade fever and bilateral leg ulcers for −10 months. He had a history of fishing in a swampy area before the occurrence of leg lesions. Skin swabs and skin biopsy from previous hospital revealed P. aeruginosa and suppurative necrosis of dermis through subcutaneous fat with dense neutrophilic infiltration, respectively. He was commenced on various intravenous antibiotics with no improvement and subsequently developed new leg ulcers with progressive leg pain. His lesions when he was referred to Siriraj Hospital are shown in Fig. 1. Physical examination revealed febrile, marked pallor, mildly icteric sclerae, hepatosplenomegaly and edema of his legs. Complete blood count showed hematocrit 11.9%, white blood cell count 13,700 cells/μl and platelet count 259,000 /μl. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing was negative. Gram stain, acid fast stain, modified acid fast stain, and Wright’s stain performed on discharge of the leg ulcers did not show any organisms. Pythiosis was suspected because of the history of thalassemia and exposure to swampy area. Prompted serum immunochromatographic (ICT) and immunodiffusion (ID) tests were done and showed positive results for P. insidiosum antibody. Emergency computed tomography angiography (CTA) of abdomen and legs demonstrated occlusion of distal part of right peroneal, dorsalis arteries, left dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries. Small aneurysms with total occlusion at distal part of left anterior tibial artery were also found (Fig. 2). The second skin biopsy revealed lobular panniculitis with marked tissue necrotizing inflammation. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers for detection of P. insidiosum deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in paraffin embedded tissue was also positive for P. insidiosum DNA (Fig. 3). Human vascular pythiosis was diagnosed and treatment was commenced with oral terbinafine 250 mg/day in combination with itraconazole 400 mg/day. In addition, immunotherapy using modified P. insidiosum antigens (PIA) was initiated however a cutaneous reaction from a test dose showed signs of a poor response. Four days after immunotherapy, he developed swelling and pain on his right knee. Joint effusion from arthrocentesis was positive for P. insidiosum antibody by ID test. The repeated CTA demonstrated a new mycotic aneurysm of left anterior tibial artery. As a result of progressive disease, emergency bilateral above knee amputations (about 10 cm) were undertaken. Fresh tissue was stained with potassium hydroxide (KOH) revealing non-septate hyaline hyphae on arterial walls of both legs. Immunotherapy, oral terbinafine and itraconazole were planned to continue for at least one year although the optimal duration of treatment is currently unknown. He was discharged from the hospital after +33 days of admission. The patient has been followed up and remains stable without any signs of recurrence for at least +18 months. Thus, immunotherapy and oral antifungal drugs are discontinued. He has been scheduled for leg prosthesis.

Fig. 1.

Bilateral leg ulcers.

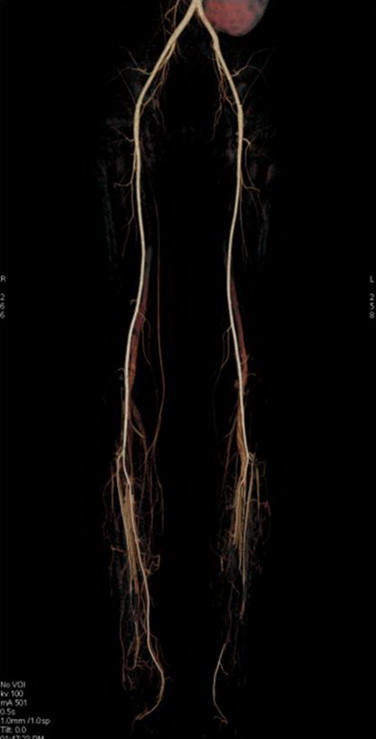

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography angiography showed total occlusion of distal part of right peroneal artery and middle part of left posterior tibial artery.

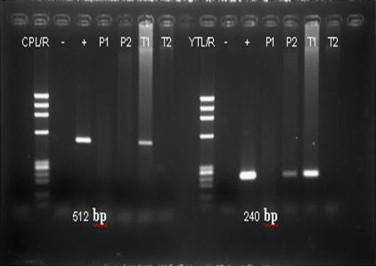

Fig. 3.

Paraffin embedded tissue (P2) was positive for Pythium insidiosum (240 bp) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique. Tissue from left posterior tibial artery (T1) was positive for both Pythium sp. (512 bp) DNA and Pythium insidiosum (240 bp) DNA.

3. Discussion

Pythiosis is caused by P. insidiosum, the only Pythium species of the Kingdom Chromista (Stramenopila) that has been implicated in human and animal infections [3,4]. It has been reported worldwide especially from tropical, subtropical, and temperature areas [5,6]. The first case of human pythosis was reported from Thailand in 1985 [4]. P. insidiosum presents in two forms: perpendicular branching hyphae and biflagellate zoospore which shares some morphologic characteristics with fungal members of the order Zygomycetes. However, phylogenic analysis shows that Pythium species are more closely related to diatoms and algae than true fungi. Zoospores are the infectious units which develop only in water. At the optimal temperatures (34–36 °C), zoospores can produce germ tubes in host skin and then slowly progress into blood circulation [7].

Clinical presentations of human pythiosis can be classified into four types: cutaneous/subcutaneous, vascular, ocular, and disseminated forms. Cutaneous/subcutaneous infection can lead to vascular and disseminated diseases. The majority of the patients affected with cutaneous, vascular and disseminated forms have underlying thalassemia/hemoglobinopathy syndrome while a minority of them have underlying aplastic anemia-paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Ocular pythiosis is exceptional in that it can affect otherwise healthy individuals [2]. Patients with vascular pythiosis usually present with chronic arterial insufficiency syndrome of unilateral leg, which varies from intermittent claudication to gangreonous ulceration. Bilateral involvement, as in our patient, has rarely been reported. Table 1 summarizes clinical features, treatment and outcomes of case reports with vascular pythiosis of both legs [8–11].

Table 1.

Case reports with vascular pythiosis of both legs.

| Case (Ref.) | Career | Age (Y)/Sex | Underlying disease | Clinical manifestations | Vascular involvement | Therapy |

Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Medication | |||||||

| 1 [8] | Farmer | 35/F | aHet. bthal. HbE | Rt. Leg gangrene, Lt. leg ischemia | Infrarenal aortic occlusion | Resection with graft bypass | Amphotericin B | Died 10 months after surgery |

| 2 [9] | Farmer | 34/M | bThal HbH & HbCS | Gangrene of both legs (Lt.>Rt) | Lt. external iliac artery and Rt. common iliac artery occlusion | Amputation & aorto-femoral bypass | None | Died 4 months after surgery |

| 3 [10] | NA | 17/M | Beta bthal. HbE | Gangrene of Lt. leg and Rt. flank pain | Abdominal aorta occlusion | Amputations of both legs | None | Died |

| 4 [10] | Farmer | 28/F | Beta bthal. HbE | Chronic ulcer Lt. leg, claudication of both legs | Aortic bifurcation thrombosis | Amputations of both legs | None | Died |

| 5 [10] | Farmer | 31/F | Beta bthal. HbE | Gangrene of both legs | Rt. common iliac artery thrombosis | Amputations of both legs | Amphotericin B cSSKI | Died |

| 6 [11] | NA | 63/F | AEBart’s disease | Pain and intermittent claudication of both legs | Complete obstruction of the right common iliac and left internal iliac arteries | Right femoral embolectomy and aorto femoral bypass, limb amputations and hip disarticulation | Terbinafine, Itraconazole, Immunotherapy | Died 2 months after admission |

| Our case | Truck driver | 35/M | HbH disease | Ulcer of both legs | Rt. peroneal artery and Lt. tibial artery | Above knee amputation (both legs) | Terbinafine, Itraconazole, Immunotherapy | No relapse 18 months after treatment |

Het=Heterozygous,

thal.=Thalassemia,

SSKI=saturated solution of potassium iodide.

Histopathology and angiography are not specific to diagnose pythiosis as the morphology of the organism is similar to other fungi such as mucormycosis and aspergillosis. Culture identification is a gold standard. Creamy white and glabrous colonies of P. insidiosum are usually detected after 24–48 h of incubation. However, it is a time-consuming method, and requires expertise. Molecular diagnosis (PCR) and the serological assays (immunodiffusion and immunochromatographic tests) are therefore useful to make a diagnosis of human pythyosis. Immunodiffusion test (ID) for detecting circulating P. insidiosum antibody (PIA) is convenient. However, the sensitivity of this method was 61% [12,13]. Krajaejun et al. demonstrated a more sensitive test by using rapid immunochromatographic test (ICT) for diagnosis of vascular and cutaneous pythiosis [13]. Both tests have 100% specificity but the sensitivity of ICT is higher than ID (88% and 61%, respectively). Moreover, the turnaround time of ICT is shorter than ID (30 minutes and 24 hours, respectively). It should be noted that false-negative result can occur in patients with ocular pythiosis especially by using ID test [12,13]. The data regarding validity of the ID test performed on joint effusion is still lacking.

In the absence of tissue culture, a specific diagnostic PCR using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of P. insidiosum can be used in cases which fixed tissue is submitted for histopathology. In our case, amplification of Pythium sp. was done using primer pairs CPL6: 5′–GACACAGGGAGGTAGTGACAATAAATA-3′ & CPR8: 5′–CTTGGTAAATGCTTTCGCCT–3′. In addition, the primer pairs YTL1: 5′–CTTTGAGTGTGTTGCTAGGATG–3′ & YTR1: 5′–CTGGAATATGAATACCCCCAAC–3′ was used for P. insidiosum (data has not been published). Therefore, the diagnosis of pythiosis in our patient was confirmed by in-house ID, ICT and PCR tests.

Treatment of human pythiosis is difficult. Amphotheracin B and ketoconazole do not have therapeutic activity against P. insidiosum [2,7]. Combination of terbinafine and itraconazole has been used in some patients and this combination has been reported to be successfully used in a child with inoperable facial pythiosis [14]. However, medical treatment alone seems to be ineffective against systemic or vascular pythiosis. Most patients usually require surgical removal of infected site in combination with medical treatment. Immunotherapy which is a modified P. insidiosum-antigen (PIA) formulation has been developed in 1981. It was first successfully used to save a Thai boy with vascular pythiosis in 1998 [15]. Wanachiwanawin et al. reported the efficacy of immunotherapy in eight patients with vascular pythiosis. Four patients (50%) had dramatic and complete remission while the other two (25%) showed partial response. The overall efficacy of immunotherapy in human including the first case is approximately 56% [16]. Early administration of immunotherapy is important for successful outcome. Systemic antifungal drugs and immunotherapy were firstly initiated without surgical intervention as our patients had vascular pythiosis of both legs. However, bilateral above-knee amputations were subsequently done due to deteriorative condition and life-threatening disease. After surgery, immunotherapy with PIA and antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine were continued for +18 months. A long term follow-up is necessary in order to assess the efficacy of immunotherapy and antifungal drugs in this patient.

Conflict of interest

There are none.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Dr. Carol Cunningham for all kind support.

References

- 1.Kaufman L. Penicilliosis marneffei and pythiosis: emerging tropical diseases. Mycopathologia. 1998;143:3–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1006958027581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krajaejun T., Sathapatayavongs B., Pracharktam R., Nitiyanant P., Leelachaikul P., Wanachiwanawin W. Clinical and epidemiological analyses of human pythiosis in Thailand. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43:569–576. doi: 10.1086/506353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabosa I.M., Riet-Correa F., Nobre V.M., Azevedo E.O., Reis-Junior J.L., Medeiros R.M. Outbreaks of pythiosis in two flocks of sheep in northeastern Brazil. Veterinary Pathology. 2004;41:412–415. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-4-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imwidthaya P. Human pythiosis in Thailand. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1994;70:558–560. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.70.826.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco Sde M., Bagagli E., Araujo J.P., Jr., Candeias J.M., de Franco M.F., Alencar Marques M.E. Human pythiosis, Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:715–718. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.040943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivierre C., Laprie C., Guiard-Marigny O., Bergeaud P., Berthelemy M., Guillot J. Pythiosis in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:479–481. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaastra W., Lipman L.J., De Cock A.W., Exel T.K., Pegge R.B., Scheurwater J. Pythium insidiosum: an overview. Veterinary Microbiology. 2010;146:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sathapatayavongs B., Leelachaikul P., Prachaktam R., Atichartakarn V., Sriphojanart S., Trairatvorakul P. Human pythiosis associated with thalassemia hemoglobinopathy syndrome. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1989;159:274–280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chetchotisakd P., Pairojkul C., Porntaveevudhi O., Sathapatayavongs B., Mairiang P., Nuntirooj K. Human pythiosis in Srinagarind hospital: one year's experience. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 1992;75:248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanachiwanawin W., Thianprasit M., Fucharoen S., Chaiprasert A., Sudasna N., Ayudhya N. Fatal arteritis due to Pythium insidiosum infection in patients with thalassaemia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;87:296–298. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90135-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pupaibool J., Chindamporn A., Patrakul K., Suankratay C., Sindhuphak W., Kulwichit W. Human pythiosis. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:517–518. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pracharktam R., Changtrakool P., Sathapatayavongs B., Jayanetra P., Ajello L. Immunodiffusion test for diagnosis and monitoring of human pythiosis insidiosi. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1991;29:2661–2662. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2661-2662.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krajaejun T., Imkhieo S., Intaramat A., Ratanabanangkoon K. Development of an immunochromatographic test for rapid serodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2009;16:506–509. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00276-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenep J.L., English B.K., Kaufman L., Pearson T.A., Thompson J.W., Kaufman R.A. Successful medical therapy for deeply invasive facial infection due to Pythium insidiosum in a child. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1998;27:1388–1393. doi: 10.1086/515042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thitithanyanont A., Mendoza L., Chuansumrit A., Pracharktam R., Laothamatas J., Sathapatayavongs B. Use of an immunotherapeutic vaccine to treat a life-threatening human arteritic infection caused by Pythium insidiosum. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1998;27:1394–1400. doi: 10.1086/515043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanachiwanawin W., Mendoza L., Visuthisakchai S., Mutsikapan P., Sathapatayavongs B., Chaiprasert A. Efficacy of immunotherapy using antigens of Pythium insidiosum in the treatment of vascular pythiosis in humans. Vaccine. 2004;22:3613–3621. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]