ABSTRACT

Background

Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws, including juvenile ossifying fibroma, pose diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties due to their clinical, radiological and histological variability. The aim of this study was to report the outcome of a 9 years old girl with diagnosed juvenile ossifying fibroma treatment.

Methods

A 9 years old girl presented with a 6 x 8 cm sized hard fixed tumour on right ramus and corpus of the mandible. On the radiological examination tumour showed an irregular but well bordered, unilocular and expansive lesion on the right corpus and ramus of the mandible. There was no teeth displacement or teeth root resorbtion. Microscopically, the tumour had trabeculae, fibrillary osteoid and woven bone. After the clinical, radiological (panoramic radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) and histologic analysis it was diagnosed juvenile ossifying fibroma. In the history of the patient there has been an acute lymphocytic leukaemia in the remission for 3 years.

Results

Because of large size of mandibular tumour, resultant expansion and destruction of mandibular cortex, the patient underwent right hemimandibulectomy using transmandibular approach. There was no recurrence or complications for two years follow-up.

Conclusions

Although juvenile ossifying fibroma is an uncommon clinical entity, its aggressive local behaviour and high recurrence rate means that it is important to make an early diagnosis, apply the appropriate treatment and, especially, follow-up the patient over the long-term.

Keywords: mandibular diseases, mandibular neoplasms, ossifying fibroma, oral surgery, lymphocytic leukemia.

INTRODUCTION

Fibro osseous-lesions of the cranial and facial bones are usually benign and tend to grow slowly. Benign fibro-osseous lesions have similar histopathological features with fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, and cemento-ossifiying dysplasia [1,2].

Ossifying fibroma, a rare tumour entity, is a well-demarcated benign fibro-osseous tumour with capsule composed of metaplastic bone, fibrous tissue and varying amounts of osteoid [3,4,5]. The ossifying fibromas are subdivided into conventional and juvenile clinicopathologic subtypes [3]. Conventional ossifying fibromas are usually slow growing and generally seen in the third and forth decades of life [6,7]. They are treated with simple curettage and the recurrence is rare [8]. It affects people of all ages, but in contrast to the form seen at adults, the juvenile form is clinically more aggressive and tends to be recurrent [3].

According to the new edition of the classification of the World Health Organization [9], ossifying fibromas which appear as fast growing mass between 5 and 15 years of age, radiologically well bordered, and consistent with ossifying fibroma histologically, are referred as juvenile (aggressive) ossifying fibroma.

Juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) appears at an early age and in 79% of the patients are diagnosed before the age of 15 [2,3,10]. Males and females are equally affected [11]. JOF originates from periodontal ligament and ranges 2% of oral tumours in children [13]. The JOF is located mainly (85%) in facial bones, in some cases (12%) in calvarium and very seldom (3%) extracranially [2]. Ninety percent of the lesions located in the face region, involve the sinuses, mainly the maxillary antra [2]. Mandibular lesions are seen in 10% of the cases [2,14]. The tumour is well circumscribed by a tiny sclerotic shell of bone. It appears locally aggressive with cortical disruption and involvement of many adjacent anatomical structures. This lesion has predominating soft tissue consistency with variable amounts of internal calcification and/or linear or irregular focal bone [2]. It usually shows a low density mass due to cystic changes on computed tomography (CT) scans. Following intravenous injection of iodinated contrast, the lesion may show diffuse appearance enhancement [2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important for the lesion extent evaluation, but is inadequate for bony components. It is isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images. Following gadolinium injection, there is homogeneous tumour appearance enhancement [2].

Histologically, JOF is characterized by the presence of cellular fibrous strom, garland like bony strands and cement particles [2,6,11,13]. The JOFs are classified into two distinct clinicopathological entities: the trabecular and the psammomatoid types. Trabecular JOF is distinguished by the presence of trabeculae of fibrillar osteoid and woven bone and psammomatoid JOF is characterised by the presence of small uniform spherical ossicles that resemble psammoma bodies [15]. Psammomatoid JOF is reported more commonly than trabecular JOF [14,16]. Psammomatoid JOF occurs predominantly in the sinonasal and orbital bones, and trabecular JOF predominantly affects the jaws. Psammomatoid JOF has aggressive behaviour and it has a very strong tendency to recur [15,16,17].

An accurate diagnosis of JOF is made by correlating the clinical, CT scan, MRI and histopathological findings [2]. Authors herein presents a case of juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible which caused expansion and destruction of mandibular cortex.

CASE DESCRIPTION AND RESULTS

A 9 year old girl applied to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey, complaining of a swelling on the right side of her lower jaw lasting three months. She also felt a pain and inflammation in this area. Medical history revealed acute lymphocytic leukaemia presented in remission for 3 years.

Physical examination revealed a hyperaemic swelling about 6 x 8 cm in size, causing facial asymmetry in the region of submandibular area including right corpus and ramus of the mandibule (Figure 1). Assessment with palpation showed a hard, nontender mass with smooth surface adhered to the mandible. The mouth opening of the patient was normal and there were no decayed teeth in the lesion area, but there was malocclusion. There was clear lingual expansion of the right mandible (Figure 2). Oral hygiene was good. The right palatine tonsil was deviated to the left. There were no assessed pathological changes of the mucous membrane in the tumour region.

Figure 1.

Photograph of a 9 year old girl with JOF showing unilateral swelling extending from the right submandibular to the right mandibular ramus and corpus region.

Figure 2.

Photograph of mandibular ramus and corpus region showing clear lingual expansion of the mansoble (arrow).

Panoramic radiograph showed an irregular but well bordered, unilocular, expansive lesion of the right corpus and ramus of mandible. There was no teeth displacement or teeth root resorbtion. There were registered deciduous right mandibular canine and first and second premolars. However, there were no deciduous teeth in the left side.

The CT scan of mandibular tumour showed a solid hypodense mass that enlarged the submandibular area, filled the pterygoid fossa and right masseter muscle region. The tumour was occupied and destructed the right corpus and ramus of the mandible (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CT axial image shows a lesion involving submandibular area and causing expansion and destruction of body and ramus of the right mandible (arrow). Pharyngeal air column displaced to opposite site.

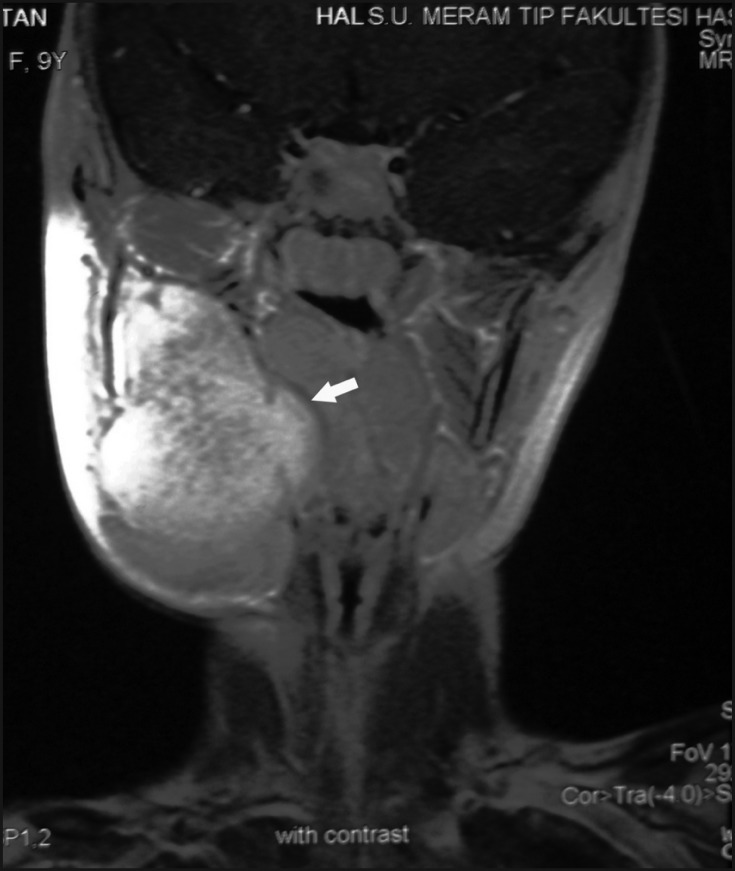

The heterogenic mass lesion caused destruction of the right ramus of mandible was seen on MRI. It was hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 4). Pharyngeal air column, hyoid bone and larynx were displaced to the opposite side (Figure 5). There was clear contrast retention following intravenous gadolinium injection.

Figure 4.

MRI axial image shows a large tumour which causes destruction of body and ramus of the right mandible (arrow).

Figure 5.

MRI coronal image shows contrast retention in the tumour (arrow) after gadolinium injection. Pharyngeal air column is displaced to opposite site.

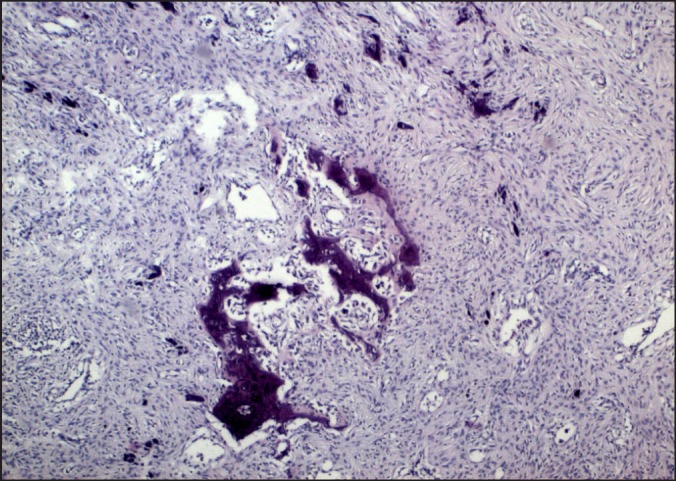

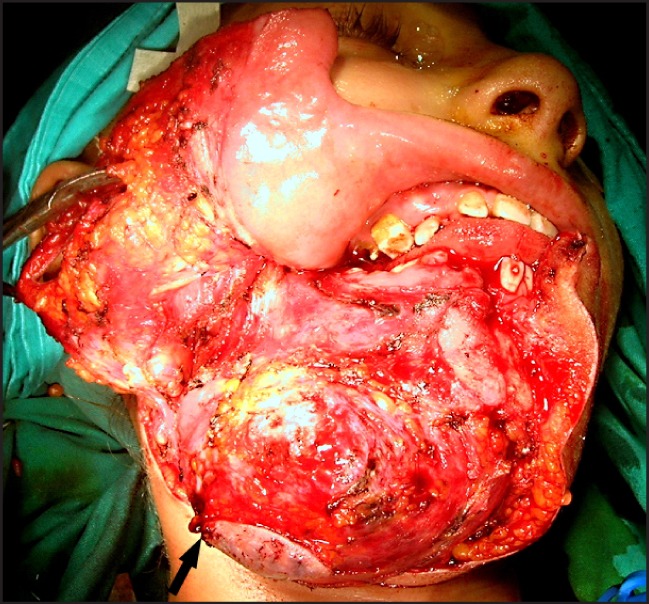

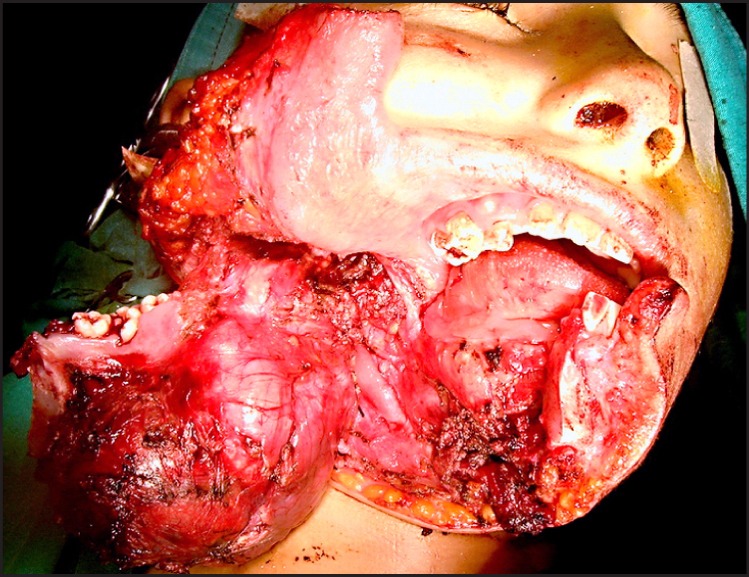

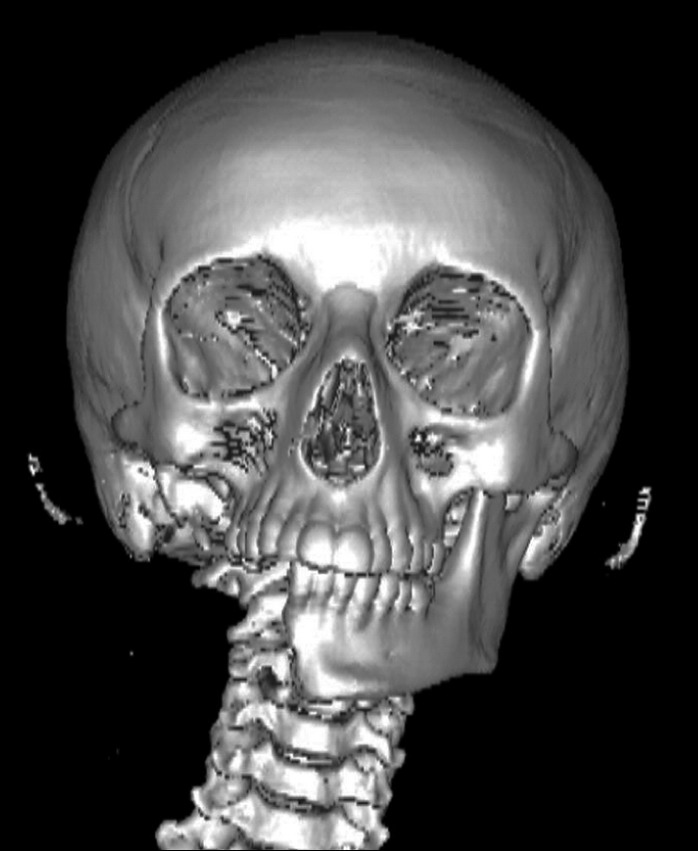

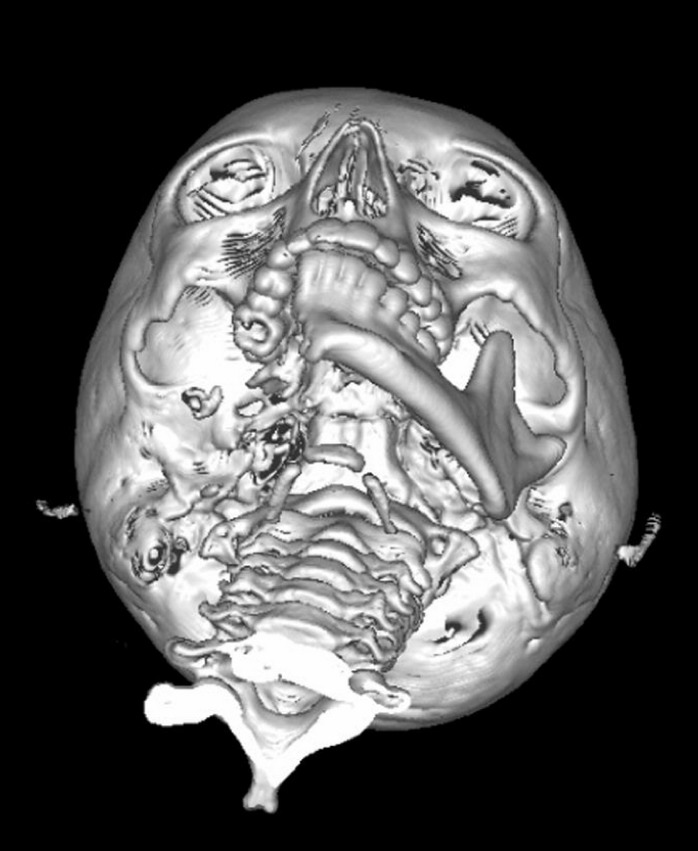

The incisional biopsy was taken from the lesion and the pathology process was reported as JOF. Diagnosis was based on the presence of trabeculae of fibrillar osteoid and woven bone fragments (Figure 6). Because of large size of the mandibular tumour, the resultant expansion and destruction of mandibular cortex, and the close adjacency to the temporomandibular joint, the patient underwent a right hemimandibulectomy using transmandibular approach (Figures 7,8,9). No recurrence was observed during the 2 years of follow-up with three dimensional CT scan and MRI (Figures 10 and 11). Oral functions of the patient (chewing, eating and speaking) were appearing intact (Figure 12).

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of tumour shows the presence of trabeculae of fibrillar osteoid and woven bone (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification x40).

Figure 7.

Intraoperative photograph showing exposed tumour using a transmandibular approach.

Figure 8.

Intraoperative photograph showing right hemimandibulectomy.

Figure 9.

Photograph of gross surgical specimen of about 13 x 8.5 x 6.5 cm in size.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional CT scan of the patient after right hemimandibulectomy.

Figure 11.

Three-dimensional CT scan shows good jaws relationship and occlusion in the left side.

Figure 12.

Photograph showing patient's postoperative appearance.

DISCUSSION

Most benign fibro-osseous lesions of jaws are asymptomatic and slowly progressing. Moreover, an unusual clinical presentation with apparent aggressive and destructive growth may be expected when the lesion is encountered in a younger patient, especially below the age of 15 years [24,26].

The JOF is a fibro-osseous lesion that occurs in the facial bones [1,2]. It is also called aggressive ossifying fibroma due to its aggressiveness and the high tendency to recur, unlike other fibro-osseous lesions, such as cemento-ossifying fibroma, which may resemble radiographically [18]. Due to its distinct histological features, JOF has been recognized as a separate histopathological entity among the fibro-osseous group of lesions [9].

JOF is a relatively rare fibro-osseous lesion of the jaws characterized by the early age of onset i.e., under 15 years of age, the location of tumour, and the radiological appearance and the tendency to recur [28].

JOF affects both males and females equally without any significant gender predilection. However some researches showed that it is more common among men [19]. In contrast, Johnson et al. [20] stated that mandibular tumours are more frequently common in girls between the age of 5 - 11 or during the second to fourth decades of life [6]. In present paper 9 years old girl was presented.

A few cases of facial trauma have been suggested as a possible etiologic factor in the JOF development [10]. There was no trauma in anamnesis of present patient, but there was an abscess previously drained from this area.

Noffke [21] after 8 year follow-up of a juvenile ossifying fibroma in the left mandible of a 4 year old boy demonstrated initial lack of radiological evidence of demarcation and subsequent eccentric enlargement, selective tooth displacement and a multilocular appearance in areas of active growth. Additionally, an aneurysmal bone cyst and a decrease in the bone content were presented in the excision specimen. Furthermore, osteblastoma, osteosarcoma and odontogenic tumours should be considered in the differential diagnosis of JOF. While the osteoblastoma is radiologically seen as cystic bone lesion with sclerotic boundary, abnormal soft tissue mass and aggressive bone destruction is seen in the osteosarcoma, and cystic lesion connected to premolar or molar teeth is seen in odontogenic tumours [3].

The JOF is characterized as expansive, having defined sclerotic borders, locally aggressive and destructive at cortex on CT scan. This lesion is observed as a soft tissue mass with internal calcification, linear or irregular bone focuses [2,22]. An increase in diffuse contrast is seen after intravenous injection [22]. Contrast increase is seen on adventitia on MRI [14]. While aggressive cortical changes are seen in juvenile form, sclerotic changes are more common in adult form [2]. JOF is isointense in T1-weighted images and hypointense or isointense in T2-weighted images. Cystic areas can be identified. Following gadolinium injection, a slight increase in contrasting is seen [2,22]. In present case, the lesion was hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 on MRI and there was clear contrast retention after the injection of contrast agent. These findings suggest that there was acute lymphocytic leukaemia in the patient's history. However, after the incissional biopsy obtained from the lesion the final diagnosis of JOF was recognized.

Ong and Siar [23] presented JOF as a progressively growing lesion that can attain an enormous size with resultant deformity if left untreated. They presented a case of large cemento-ossifying fibroma involving the left mandible in a 15 year old male patient. The long lasting history of untreated JOF resulted to spontaneous fracture of mandible. Furthermore, if JOF do not have adequate surgical treatment, it may have high rate of recurrence [4,24]. The recurrences are generally seen at early stage and they are more aggressive when compared to primary lesions [4].

There is no consensus on the treatment of JOF cases. Radical resection, local excision conservatively or enucleation with curettage are among the treatment alternatives [4,13,25]. Slootweg and Müller [10] suggested that there were no differences between the cases that have limited surgical treatment and those with major surgery in terms of results, and they recommended conservative surgery. On the other hand, Waldron et al. [26] suggested that local excision and curettage should be a more preferable method and added that local surgical excision can be applied for recurrent tumour treatment. However, rate of recurrence after conservative treatment was reported in 30 - 58% of cases [4,27,28]. Incomplete resection causes recurrence in aggressive tumours. Therefore, some authors were recommended en block resection as an adequate treatment [12,28]. Curettage together with peripheral osteotomy or sometimes segmental mandibular resection and mandibular reconstruction are suggested in prevalent or recurrent cases [4]. Sarcomatous degeneration is reported to develop in lesions that have recurrence in long term [18]. In contrast, Espinosa et al. [4] reported a case of unusual bone regeneration after resection of JOF. Secondary mandibular reconstruction with autogenous grafts was delayed due to the rapid bone formation.

Because the large size of the mandibular tumour, resultant expansion and destruction of mandibular cortex, the patient underwent right hemimandibulectomy using transmandibular approach. Zama et al. [8] in a similar case performed resection and reconstruction keeping the mandibular tissue around the temporomandibular joint. However, in present case, it was necessary to perform right hemimandibulectomy due to close localisation of the tumour to the tempormandibular joint and absence of adequate reliable surgical border. Despite of that the oral functions of the patient remained adequate. Furthermore, cosmetically tolerable appearance of the patient was achieved. There was no recurrence or complication during two years of follow-up period.

CONCLUSIONS

Although juvenile ossifying fibroma is an uncommon clinical entity, its aggressive local behaviour and high recurrence rate mean that it is important to make an early diagnosis, apply the appropriate treatment and, especially, follow-up the patient over the long-term.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

The authors report no conficts of interest related to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Fibro-osseous lesions of the face and jaws. Clin Radiol. 2004 Jan;59(1):11-25. Review. Erratum in: Clin Radiol. 2009 Jan;64(1):107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Khoury NJ, Naffaa LN, Shabb NS, Haddad MC. Juvenile ossifying fibroma: CT and MR findings. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12 Suppl 3:S109-13. Epub 2002 May 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mehta D, Clifton N, McClelland L, Jones NS. Paediatric fibro-osseous lesions of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 Feb;70(2):193-9. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Espinosa SA, Villanueva J, Hampel H, Reyes D. Spontaneous regeneration after juvenile ossifying fibroma resection: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006 Nov;102(5):e32-5. Epub 2006 Sep 12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Patil K, Mahima BG, Balaji P. Juvenile aggressive cemento-ossifying fibroma. Acase report. Indian J Dent Res. 2003 Jan-Mar;14(1):59-66. Erratum in: Indian J Dent Res. 2003 Apr-Jun;14(2):74. Corrected and republished in: Indian J Dent Res. 2003 Apr-Jun;14(2):111-9.

- 6.Chang CC, Hung HY, Chang JY, Yu CH, Wang YP, Liu BY, Chiang CP. Central ossifying fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008 Apr;107(4):288-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Alsharif MJ, Sun ZJ, Chen XM, Wang SP, Zhao YF. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws: a study of 127 Chinese patients and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009 Apr;17(2):122-34. Epub 2008 May 14. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zama M, Gallo S, Santecchia L, Bertozzi E, De Stefano C. Juvenile active ossifying fibroma with massive involvement of the mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Mar;113(3):970-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sciubba JJ. The new classification of Head and Neck Tumours (WHO)--any changes? Oral Oncol. 2006 Sep;42(8):757-8. Epub 2006 May 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Slootweg PJ, Müller H. Juvenile ossifying fibroma. Report of four cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990 Apr;18(3):125-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bertrand B, Eloy P, Cornelis JP, Gosseye S, Clotuche J, Gilliard C. Juvenile aggressive cemento-ossifying fibroma: case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 1993 Dec;103(12):1385-90. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sharif MA, Mushtaq S, Mamoon N, Khadim MT. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of oral cavity. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008 Mar;18(3):181-2. [PubMed]

- 13.Dominguete PR, Meyer TN, Alves FA, Bittencourt WS. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the jaw. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Sep;46(6):480-1. Epub 2008 Feb 21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lawton MT, Heiserman JE, Coons SW, Ragsdale BD, Spetzler RF. Juvenile active ossifying fibroma. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 1997 Feb;86(2):279-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.El-Mofty S. Psammomatoid and trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma of the craniofacial skeleton: two distinct clinicopathologic entities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002 Mar;93(3):296-304. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Thankappan S, Nair S, Thomas V, Sharafudeen KP. Psammomatoid and trabecular variants of juvenile ossifying fibroma-two case reports. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2009 Apr-Jun;19(2):116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Solomon M, Khandelwal S, Raghu A, Carnelio S. Psammomatoid Juvenile Ossifying Fibroma of the Mandible – A Histochemical insight!. The Internet Journal of Dental Science [1937-8238] 2009;7(2). Available from: http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_dental_science/volume_7_number_2_20/article/psammomatoid-juvenile-ossifying-fibroma-of-the-mandible-a-histochemical-insight.html.

- 18.Brannon RB, Fowler CB. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: a review of current concepts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001 May;8(3):126-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Rinaggio J, Land M, Cleveland DB. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible. J Pediatr Surg. 2003 Apr;38(4):648-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Johnson LC, Yousefi M, Vinh TN, Heffner DK, Hyams VJ, Hartman KS. Juvenile active ossifying fibroma. Its nature, dynamics and origin. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;488:1-40. Review. [PubMed]

- 21.Noffke CE. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible. An 8 year radiological follow-up. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1998 Nov;27(6):363-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bendet E, Bakon M, Talmi YP, Tadmor R, Kronenberg J. Juvenile cemento-ossifying fibroma of the maxilla. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997 Jan;106(1):75-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ong AH, Siar CH. Cemento-ossifying fibroma with mandibular fracture. Case report in a young patient. Aust Dent J. 1998 Aug;43(4):229-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Williams HK, Mangham C, Speight PM. Juvenile ossifying fibroma. An analysis of eight cases and a comparison with other fibro-osseous lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000 Jan;29(1):13-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Saiz-Pardo-Pinos AJ, Olmedo-Gaya MV, Prados-Sánchez E, Vallecillo-Capilla M. Juvenile ossifying fibroma: a case study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2004 Nov-Dec;9(5):456-8; 454-6. English, Spanish. [PubMed]

- 26.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993 Aug;51(8):828-35. Review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Shekhar MG, Bokhari K. Juvenile aggressive ossifying fibroma of the maxilla. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2009 Jul-Sep;27(3):170-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Sun G, Chen X, Tang E, Li Z, Li J. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the maxilla. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 Jan;36(1):82-5. Epub 2006 Oct 2. [DOI] [PubMed]