Abstract

Commonly used general anesthetics can have adverse effects on the developing brain by triggering apoptotic neurodegeneration, as has been documented in the rat. The rational of our study was to examine the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the apoptotic action of propofol anesthesia in the brain of 7-day-old (P7) rats. The down-regulation of nerve growth factor (NGF) mRNA and protein expression in the cortex and thalamus at defined time points between 1 and 24 h after the propofol treatment, as well as a decrease of phosphorylated Akt were observed. The extrinsic apoptotic pathway was induced by over-expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) which led to the activation of caspase-3 in both examined structures. Neurodegeneration was confirmed by Fluoro-Jade B staining. Our findings provide direct experimental evidence that the anesthetic dose (25 mg/kg) of propofol induces complex changes that are accompanied by cell death in the cortex and thalamus of the developing rat brain.

Keywords: Propofol, Postnatal rat, NGF, TNF, Caspase-8, Caspase-3

1. Introduction

Data that has been accumulating in the past decade is placing increasing importance on the neurotoxic effects of different general anesthetic agents on the postnatal developing brain (Olney et al., 2000). Anesthesia-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration is age-dependent and closely correlates with the timing of synaptogenesis. Namely, the developing brain is most sensitive when synaptogenesis is at its peak (Yon et al., 2005).

The mechanisms of the toxic effects on the central nervous system that are induced by anesthetic agents remain poorly understood. It has been suggested that anesthesia-induced neurodegeneration involves the activation of both mitochondrial (intrinsic) and death receptor-mediated (extrinsic) apoptotic pathways (Yon et al., 2005). They both converge on the activation of executioner caspase-3 which subsequently cleaves multiple downstream cellular targets (Regula and Kirshenbaum, 2005). However, the recent report of Lu et al. (2006) pointed to the role of neurotrophins, suggesting that general anesthetics with a clinical application (e.g. midazolam-nitrous oxide-isoflurane), induce neuroapoptotic damage in the developing brain of immature rats mediated, at least in part, through the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-modulated apoptotic cascade.

Neurotrophins were initially considered as target-derived neuronal survival factors, however, they are now recognized as mediators of a wide range of responses that include maintenance of survival and induction of apoptosis (Bibel and Barde, 2000; Roux and Barker, 2002). The signal transduction systems that mediate the diverse biological functions of the neurotrophins are initiated through interactions with two categories of cell surface receptors, the tropomyosin-related kinase (Trk) tyrosin kinase receptors and the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR; Roux and Barker, 2002). These receptors that are often present on the same cell coordinate and modulate the responses of neurons to neurotrophins. Neurotrophin binding to Trk activates a number of signaling pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway important for neurotrophin-mediated survival of neurons (Arevalo and Wu, 2006). Importance of this signaling pathway for is well documented (Crowder and Freeman, 1998; Dudek et al., 1997; Kaplan and Miller, 2000; Volosin et al., 2006).

The basic machinery for apoptosis is constitutively expressed in most if not in all cells and is regulated by the equilibrium of life and death signals. The nature of these interactions is not completely understood. During brain development when apoptosis plays a fundamental role in regulating cell fate, the neurotrophins antagonize naturally occurring programmed cell death and thus promote neuronal survival in mammals (Kaplan and Miller, 2000). Nerve growth factor (NGF) and presumably other neurotrophic factors, maintain neuronal survival by suppressing the active death program (Martin et al., 1988). Also, a novel view of neurodegeneration has recently emerged in which a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor induces death through the ‘silencing of survival signals’ (SOSS; Venters et al., 2000). Elucidation of the crosstalk between growth factor signaling pathways and extrinsic apoptotic pathways is important as it may prove to be essential in determining cell survival.

In the present study, we examined the effects of propofol anesthesia in 7-day-old (P7) rats (at the peak of brain development) on two of the most vulnerable brain regions – the cerebral cortex and thalamus. Propofol is an intravenous anesthetic used for the induction of anesthesia as well as its maintenance either by continuous infusion or by administration of intermittent bolus doses (Trapani et al., 2000). Although there is controversy with regard to the use of propofol in children, at present it is commonly administered to young children, including neonates (Westrin, 1991; Wooltorton, 2002).

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms that are induced by propofol anesthesia, we investigated the changes in expression of NGF and members of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway (TNFα, caspase-8). Apoptotic neurodegeneration was assessed by changes in active caspase-3 expression that were confirmed by Fluoro-Jade B staining. Our findings provide direct experimental evidence about pro-apoptotic effect of short-term propofol anesthesia in the cortex and thalamus of P7 rats.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Propofol (Recofol®) was obtained from Schering (Turku, Finland). Rabbit polyclonal antibody NGF (H-20) (sc-548), goat polyclonal antibody TNFα (M-18) (sc-1348), rabbit polyclonal antibody p-Akt1/2/3 (Thr-308)-R (sc-16646-R), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG (sc-2020) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc-2004) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) antibody (#9661) was purchased from Cell Signalling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-β-actin rabbit polyclonal antibody (A-5060) was purchased from Sigma. The ECL-plus kits were purchased from Amersham (Otelfingen, Switzerland). Fluoro-Jade B (AG310) was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). TRIZOL reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Oligo-dT primers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase was purchased from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). Reagents for semiquantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were purchased from Fermentas (Vilnius, Lithuania). RT-PCR High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit, Assay-on-Demand Gene Expression Products for NGF β (ID Rn01533872_m1), caspase-8 (ID Rn00574069_m1), GAPDH (ID Rn99999916_s1) and other reagents for real-time PCR were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

2.2. Animals and treatment

All experiments were performed in accordance with approved institutional animal care guidelines. Seven-day-old (P7) Wistar rat pups with an average body weight of 14 g were used in the experiments. As at this time point brain development is at its peaks, it is very vulnerable to anesthesia-induced apoptotic damage.

Animals were treated with propofol manufactured for i.v. human use (Recofol®). The formulation contained in addition to the active substance, soybean oil, purified egg phosphatide, glycerol and sodium hydroxide to adjust the pH. The ampoules were shaken well and the drug was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

All experiments were approved by the institutional committee as well as by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health).

We first performed an experiment in order to obtain the dose of propofol for the main study. Rat pups (n = 20) were separated from their mothers and placed in a temperature-controlled incubator set to an ambient temperature of 35 °C. The animals were randomly divided into four groups (n = 5) and injected i.p. with 10, 20, 25 or 50 mg/kg of propofol. Loss of the righting reflex served as an indicator of anesthetic-induced unconsciousness and sleeping time. The animal was considered to have lost the righting reflex if it was unable to stand on its feet. The length of time required for loss of the righting reflex was defined as the time between the injection and the point at which the animal could no longer successfully perform the righting response when placed on its back. The times of loss and recovery of the righting reflex (measured in min) were recorded with a stopwatch. We also used the tail pinching test to examine pain sensation in the anesthetized animals. Changes in skin color were also noted. The animals that were used in this experiment were not used in any other experiments.

Observations obtained from the above-described experiment are presented in Section 3. We opted for the dose of 25 mg/kg of propofol which was subsequently used in the main experiment

2.3. Experimental procedure

For Western blot and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses n = 56 rat pups were used. They were separated from their mothers and placed in a temperature-controlled incubator. The animals were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 8) and injected with propofol (25 mg/kg, i.p.). They were decapitated at different time points after the treatment: at 0 h (the control), 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h. Animals that were to be killed after 4 or more hours after the treatment were allowed to recover in the incubator for 2 h and were then returned to their mothers to feed.

For Fluoro-Jade B staining n = 12 rat pups were used; n = 4 rats were treated with propofol (25 mg/kg). Physiological controls (n = 4) were injected with an appropriate volume of saline; n = 4 rats were treated with two i.p. doses (0.5 mg/kg) of (+) MK-801 (Ikonomidou et al., 1999; Hansen et al., 2004) at 8 h intervals (positive control); the rats were killed 24 h after the first injection.

2.4. Tissue preparation

Rat pups were sacrificed at different time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h after the propofol treatment; n = 8 per group). The cortex and the thalamus from both hemispheres were dissected on ice. Due to the small size of the immature rat brain, protein and RNA were prepared from two different tissue homogenates that were obtained from four pooled brains per time point. The samples were stored at −70 °C.

2.5. Protein isolation and Western blot analysis

The tissues were homogenized and sonicated in 10 volumes of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After 30 min incubation on ice, the lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C until required.

Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford (1976). Forty micrograms of the protein extracts were heat denaturated (5 min, 95 °C) in Leammli’s sample loading buffer, separated on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels by electrophoresis, and electro-transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific protein binding was prevented by treating the membrane with blocking buffer containing 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline/0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in a blocking buffer. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-NGF (13 kDa), anti-TNFα (17 kDa), anti-p-Akt1/2/3 (Thr-308)-R (54 kDa), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (17–19-kDa fragments), anti-β-actin (42 kDa). Secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and donkey anti-goat) in Tris-buffered saline/0.1% Tween-20 were used (60 min incubation, room temperature). Three washes with 0.3% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline were performed between all steps. The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and subsequent exposure on an X-ray film. All films were densitometrically analyzed using the computerized image analysis program, ImageQuant 5.0.

2.6. Fluoro-Jade B histochemistry and image analysis

The animals were killed 24 h after the initial injection. The brains were removed and fixed overnight at 4 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The brains were cryoprotected by three 24-h incubations at 4 °C in increasing sucrose concentration solutions (10%, 20%, and 30%) in PBS. After incubation in 30% sucrose for 24 h, the brains were frozen in an isopentane bath and stored at −70 °C. Every fifth coronal section (18 μm) was taken, mounted on the slides, allowed to dry overnight and stored at −20 °C.

Degenerating neuronal somata and their processes were detected with Fluoro-Jade B as described by Schmued and Hopkins (2000). The tissue sections were examined with an Axio Observer Microscope Z1 (ZEISS) using a filter system suitable for visualizing fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Cells labeled with Fluoro-Jade B were observed as individual shiny spots clearly discernible from the background.

In control and propofol-treated animals, the number of dying neurons labeled by Fluoro-Jade B was counted at a 20× magnification under the area of the screen (0.38 mm2) in the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex and in the laterodorsal thalamus in five representative sections per animal (n = 4 per group).

(+)MK-801-treated rats served as a positive control. They were subjected to the Fluoro-Jade B assay without quantitative analysis.

2.7. RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from tissue using TRIZOL reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue samples were homogenized at a ratio of 1 ml reagent: 0.1 g tissue. RNA integrity was assessed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel. RNA concentrations were estimated by UV spectrophotometry. Total RNA was treated with 10 U of RNase free DNase I and dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water.

2.8. Reverse transcription and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed with 5 μg total RNA using oligo-dT primers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were performed in pairs since a reference gene for the normalization of target gene expression was included. The reference gene for TNFα was glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are shown in Table 1. The GAPDH:TNFα primer ratio of 1:3 (0.07 μM:0.21 μM final concentrations) allowed for linear amplification conditions. 200 ng of cDNA were used for each reaction. PCR reactions were performed in the GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems) All PCR reactions were performed from two independent RT reactions in at least two repeats from each. The PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light. Multi-Analyst/PC Software Image Analysis System (Bio-Rad Gel Doc 1000) was used for densitometry analysis.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and annealing temperature used for semiquantative RT-PCR analyses.

| cDNA | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | Annealing temperature (°C) | No. PCR cycles | Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNFα | GCCCTAAGGACACCCCTGAGGGAGC | TCCAAAGTAGACCTGCCCGGACTCC | 58 | 28 | 158 bp | Yakovlev and Faden (1994). |

| GAPDH | CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT | AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC | 58 | 28 | 306 bp | Wong et al. (1994). |

2.9. Reverse transcription and real- time RT-PCR

The RT reactions were performed in 20 μl using a High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were carried out under RNase-free conditions at 25 °C for 10 min and at 37 °C for 2 h. Each RT reaction was accompanied by a no RT control in which the reverse transcriptase was replaced by DEPC-treated water. The cDNA was stored at −20 °C until further use.

TaqMan real-time RT-PCR reactions were performed using Assay-on-Demand Gene Expression Products for NGFβ and caspase-8. The gene expression assay contained primers for amplification of the target gene and TaqMan MGB probe 6-FAM dye-labeled for the quantification. Reactions were performed in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 1× TaqMan Universal Master Mix with AmpErase UNG, 1× Assay Mix and cDNA template (10 ng of RNA converted to cDNA). PCR reactions were carried out in the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, and at 60 °C for 1 min. Each sample was run in triplicate and the mean values of each Ct were used for further calculations. A reference endogenous control was included in every analysis to correct for differences in the inter-assay amplification efficiency. Validation of endogenous control genes was performed as described previously (Tanic et al., 2007), with GAPDH and β-actin exhibiting the most stable expression. For the quantification, additional validation of the efficiencies of GAPDH, β-actin, NGFβ, and caspase-8 amplification was performed. Serial cDNAs dilutions were amplified by real-time RT-PCR using specific primers and fluorogenic probes for all tested genes. GAPDH had the same efficiency of amplification with NGF and caspase-8. Quantification was performed by the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The results obtained by RT-PCR were analyzed by RQ Study Add ON software for 7000 v 1.1 SDS instrument (ABI Prism Sequence Detection System) with a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.05). The fold-change of mRNA levels was expressed relative to the calibrator, 0h control sample that was assumed as the control value (100%).

2.10. Statistical analysis

The relative changes in mRNA and protein levels, as well as the changes in the number of Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells are presented as percentages (mean ± SEM) of the control samples assumed to be 100%. Further statistical analysis was made with relative values. Comparisons between the groups were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher LSD test, or by Kruskal–Wallis analysis that was followed by the U-test for data sets that did not have a normal distribution. The data obtained by Fluoro-Jade B staining (the number of labeled cells, control vs. propofol treated) was analyzed by the t-test. A p < 0.05 was used to determine significance.

3. Results

3.1. Propofol caused a dose-dependent loss of the righting reflex in P7 rats

To assess the optimal dose of propofol that was capable of inducing effective anesthesia we intraperitoneally injected 10, 20, 25 and 50 mg/kg of propofol and examined the behavior of P7 pups for the next 100 min. The lowest dose of propofol (10 mg/kg, i.p.) had no effect on the righting reflex although it resulted in some transient sluggishness. Two higher doses caused almost immediate loss of the righting reflex (within the first couple of minutes), accompanied by an absence of response to painful stimuli (i.e. the tail pinch). Although the tail response was restored in about 10–13 min, the righting reflex was impaired for about 40 min and 60 min for 20 and 25 mg/kg doses of administered propofol, respectively. None of the three doses caused any changes in skin color and breathing patterns. However, the propofol dose of 50 mg/kg immediately induced loss of the righting reflex and promoted cyanotic changes in skin color. Two of five rat pups died whereas in the other three pups changes in skin color persisted for about 15 min. Based on these observations we performed all subsequent experiments with 25 mg/kg propofol.

3.2. Propofol caused a significant decrease in NGF mRNA levels in the developing cortex but not in the thalamus of P7 rats

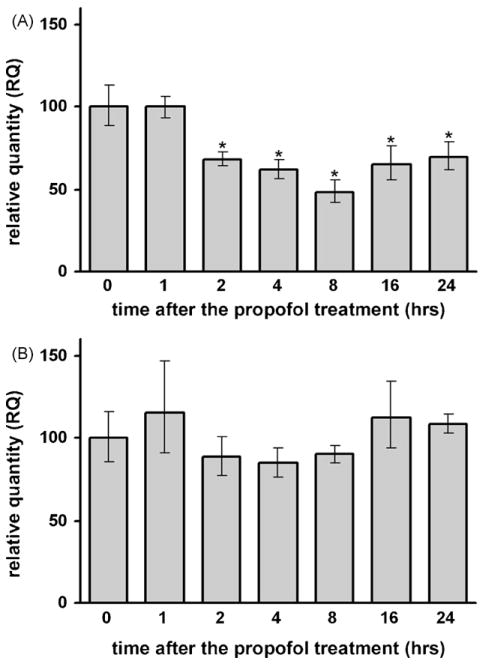

Real-time PCR revealed that propofol treatment caused a significant decline (*p < 0.05) in the NGF mRNA levels in the cortex relatively early, by 2 h post-treatment. A maximal decline was recorded at 8 h (a 2-fold decrease compared to the 0 h time point) (Fig. 1A). NGF mRNA levels remained significantly decreased up to 24 h post-treatment. The thalamus was less sensitive to propofol-induced changes in NGF mRNA levels. A transient decrease was recorded at 2 h post-treatment, followed by relatively stable levels up to 24 h (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent changes in NGF mRNA expression in the cortex (A) and thalamus (B) of P7 rats after the propofol treatment, as revealed by real-time RT-PCR. A significant decrease of NGF mRNA expression was observed in the cortex (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

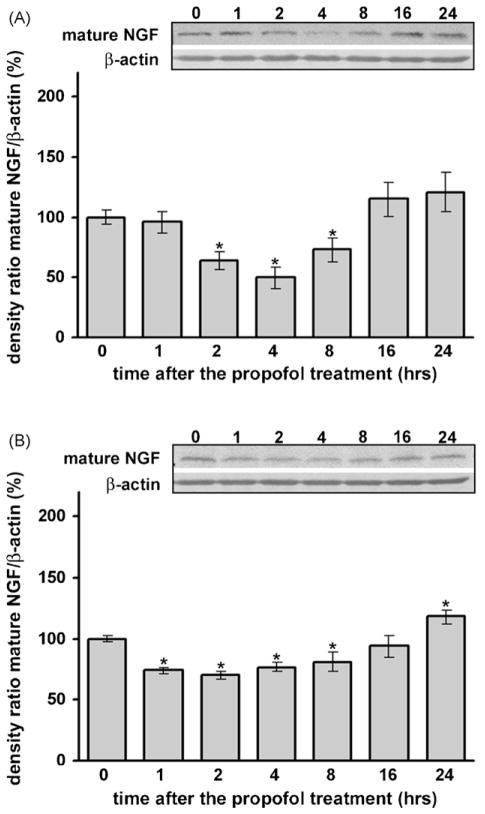

3.3. Propofol caused a significant decrease in NGF protein levels in the developing cortex and in the thalamus of P7 rats

Using Western blot analysis we detected significant down-regulation of NGF protein levels in both the cortex (Fig. 2A) and the thalamus (Fig. 2B) compared to their respective controllevels(at 0 h). In the cortex, this decrease was observed early and was most pronounced between 2 and 8 h post-treatment (*p < 0.05). In the thalamus, significant down-regulation was detected earlier, at 1 h post-treatment, and the change remained significant up to 8 h (*p < 0.05). Note that the magnitude of NGF protein down-regulation was greater in the cortex than in the thalamus (a 50% decrease was measured in the cortex compared to a 25% decrease in the thalamus, with respect to the 0 h time point). Data analysis by one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time after the treatment for both structures (for the cortex: F(6, 28) = 6.208, p = 0.001; for the thalamus: F(6, 28) = 9.422, p = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Time-dependent changes in mature NGF expression in the cortex (A) and thalamus (B) of P7 rats after the propofol treatment, as revealed by Western blotting. Each graph is accompanied by a representative immunoblot. A significant decrease of mature NGF expression was observed in both structures (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

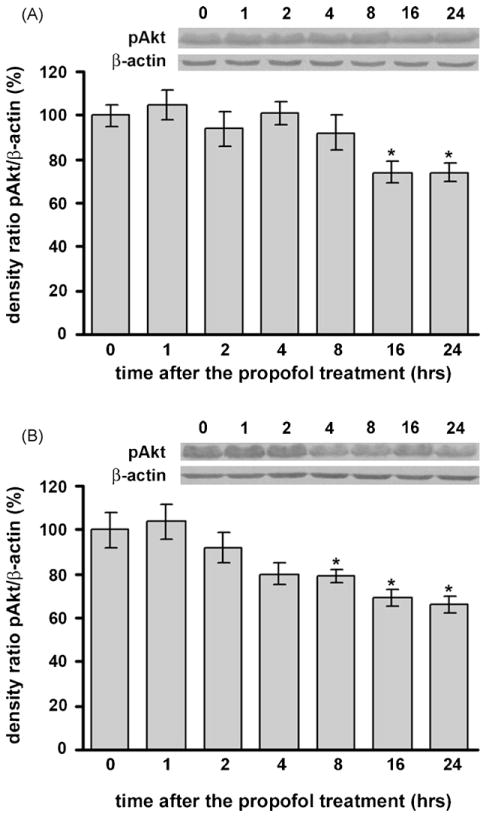

3.4. Propofol caused a significant decrease in phosphorylated Akt levels in he developing cortex and in the thalamus of P7 rats

Using Western blot analysis we detected significant down-regulation of phosphorylated Akt levels in both the cortex (Fig. 3A) and thalamus (Fig. 3B) compared to their respective control levels at 0 h. In the cortex, this decrease was observed at 16 h post-treatment, while in the thalamus significant down-regulation was detected earlier, at 8 h post-treatment. In both structures the change remained significant up to 24 h (*p < 0.05). One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time after the treatment for both structures (cortex: F(6, 28) = 4.695, p = 0.005; thalamus: F(6, 28) = 6.139, p = 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Time-dependent changes in phosphorylated Akt expression in the cortex (A) and thalamus (B) of P7 rats after propofol treatment, as revealed by Western blotting. Each graph is accompanied by a representative immunoblot. A significant decrease of phosphorylated Akt expression was observed in both structures (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

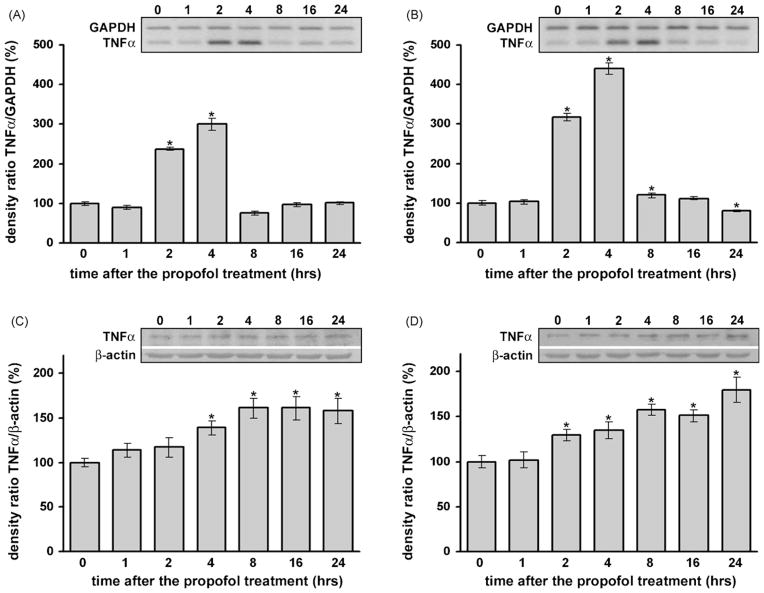

3.5. Propofol induced up-regulation of mRNA expression and protein levels of TNF-α in the developing cortex and in the thalamus of P7 rats

Compared to the control group a significant increase in TNF-α mRNA expression was observed from 2 to 4 h in the cortex (Fig. 4A, *p < 0.05) and from 2 to 8 h in the thalamus (Fig. 4B, *p < 0.05) by RT-PCR. The up-regulation was substantial and a peak increase (3-fold in the cortex and 4-fold in the thalamus) was detected 4 h after propofol administration. Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time after the treatment for both structures (P7 cortex: H(6, N = 42) = 32.404, p = 0.001; P7 thalamus: F(6, N = 35) = 31.928, p = 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent changes in TNFα mRNA and protein expression in the cortex and thalamus of P7 rats after the propofol treatment. A significant increase in TNFα mRNA expression, revealed by RT-PCR, was observed at similar times in the cortex (A) and in the thalamus (B) (*p < 0.05 vs. control). The levels of TNFα protein, as revealed by Western blotting, were significantly increased between 4 and 24 h after the treatment in the cortex (C) and between 2 and 24 h after the treatment in the thalamus (D) (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

Likewise, the analysis of TNF-α protein levels showed significant up-regulation, starting from 4 h in the cortex (Fig. 4C, *p < 0.05) and 2 h in the thalamus (Fig. 4D, *p < 0.05), compared to the respective controls (0 h). The most prominent increase was observed at the 8 h time point. The effect of propofol was long lasting since even at 24 h post-treatment there was a significant (more than 50%) increase compared to the 0 h time point in both the cortex and thalamus. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time after the treatment for both structures (cortex: F(6, 28) = 6.261, p = 0.001; thalamus: F(6, 28) = 11.129, p = 0.001).

Despite the observed changes in TNFα mRNA and protein levels, we did not observe changes in mRNA and protein levels of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) (data not shown).

3.6. Propofol induced a significant increase in caspase-8 mRNA levels in the developing cortex and thalamus of P7 rats

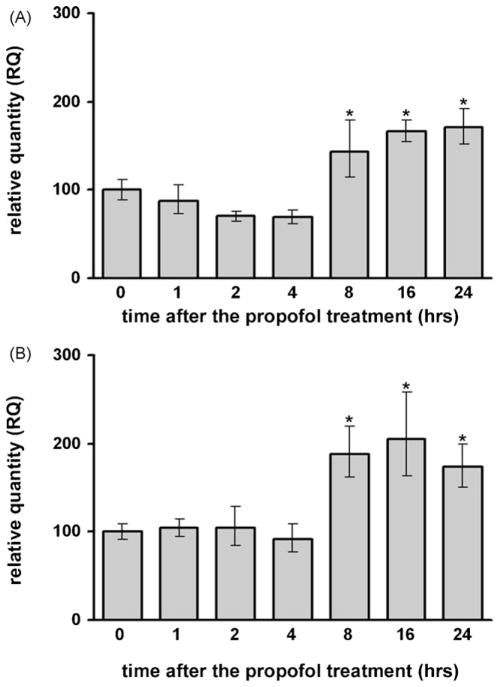

The expression of caspase-8 mRNA in the cortex (Fig. 5A) and in the thalamus (Fig. 5B) was increased in propofol-treated animals at 8 h after the treatment. It remained significantly elevated up to 24 h.

Fig. 5.

Time-dependent changes in caspase-8 mRNA expression in the cortex (A) and thalamus (B) of P7 rats after the propofol treatment, as revealed by real-time RT-PCR. A significant increase in caspase-8 mRNA expression was detected between 8 and 24 h after the treatment (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

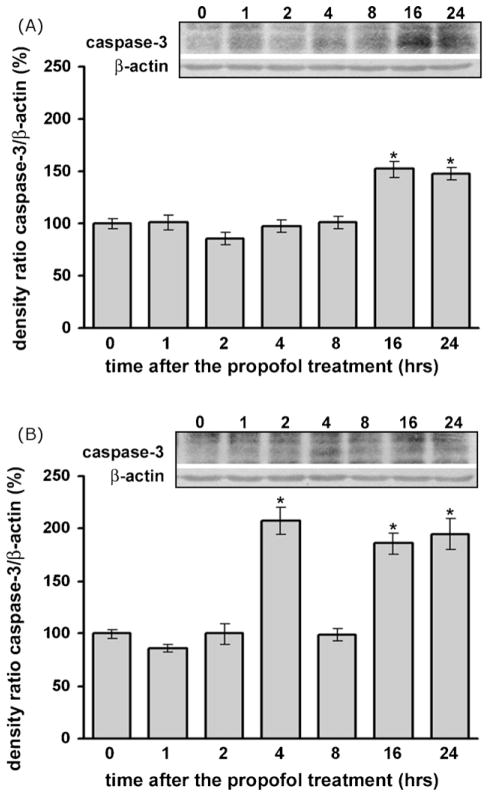

3.7. Propofol induced neuroapoptosis in the developing cortex and thalamus by activating caspase-3

Western blot analysis revealed a significant increase in the expression of the active subunit of caspase-3 (17 kDa fragment) in the cortex and thalamus, suggesting that the activity of the protease increased in both examined structures after the propofol treatment (Fig. 6). Although there was a transient (and very robust) increase in caspase-3 levels at 4 h in the thalamus, both the cortex and thalamus exhibited significant caspase-3 elevation at 16 h post-treatment and thereafter, when compared to the 0 h time-point (approximately 50% increase, *p < 0.05). Data analysis by Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the time after the treatment for both examined structures (P7 cortex: H(6, N = 28) = 19.367, p = 0.004; P7 thalamus: F(6, N = 35) = 26.716, p = 0.001).

Fig. 6.

Time-dependent changes in activated caspase-3 expression in the cortex (A) and thalamus (B) after the propofol treatment, as revealed by Western blotting. The expression of cleaved caspase-3 protein was significantly increased in both structures after the propofol treatment (*p < 0.05 vs. control).

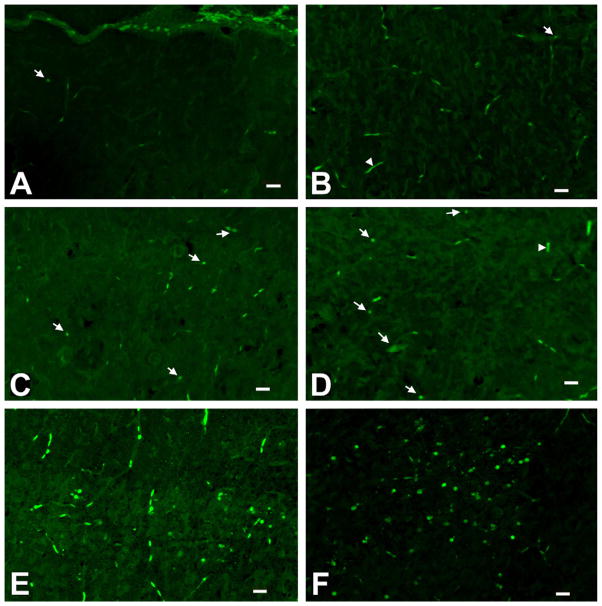

Histological analysis of degenerated neurons revealed the presence of sparsely stained Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells in control cortex (Fig. 7A) and anterior thalamus (Fig. 7B). However, increased number of Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells scattered throughout the cortex and the anterior thalamus of P7 rats 24 h after the propofol treatment is detected compared to control, especially in the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 7C) and in laterodorsal thalamic region (Fig. 7D). Quantitative analysis of Fluoro-Jade B staining revealed increases in the number of positive cells in the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex and in the laterodorsal thalamus, 185 ± 15% (*p < 0.05) and 205 ± 10% (*p < 0.05), respectively, compared to the controls. Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells in the (+)MK-801 experiments served as a positive control (Fig. 7 E and F).

Fig. 7.

Fluoro-Jade B staining of frozen brain sections. Controls (saline-injected rats killed 24 h after the injection) had a few Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex (A) and laterodorsal thalamus (B). The densest labeling was found in the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex (C) and the laterodorsal thalamus (D) of animals that were treated with propofol (25 mg/kg) and killed 24 h post-injection. Rats treated with two i.p. doses (0.5 mg/kg) of (+) MK-801 and killed 24 h after the first administration of the drug served as a positive control (E – posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex; F – laterodorsal thalamus). Degenerating neurons are marked with arrows and the blood vessels with arrowheads. Normal neurons appear darker than the background. Scale bar – 20 μm.

4. Discussion

In the present study we describe the cell death effect of short-term propofol anesthesia in the cortex and thalamus of P7 rats. In both structures, neurodegeneration was induced in a neurotrophic- and extrinsic apoptotic pathway-dependent manner. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the molecular mechanisms that contribute to the apoptotic action of propofol anesthesia in the neonatal rat brain.

The pharmacokinetics of propofol in neonates is a relatively unexplored field. The study of Allegaert et al. (2007) represents the first population analysis of preterm and term neonates. The authors explored the pharmacokinetics and its covariates following an i.v. single bolus administration of 3 mg/kg propofol. The anesthetic doses of propofol in postnatal rats have yet to be defined. The dose of propofol used in our study is much higher than the dose applied in humans (neonates). However, the dosing paradigms used in animal studies typically do not reflect the doses administered to pediatric patients (Wang and Slikker, 2008). Although most human anesthetics can be used in animals, their anesthetic effects can differ between species. Also, in small rodents venous puncture is difficult and anaesthetic agents are generally injected intraperitoneally or intramuscularly (Bazin et al., 2004). We applied propofol intraperitoneally.

It was shown recently that anesthesia-induced neuroapoptotic damage in the developing brain of the immature rats is mediated, at least in part, by the BDNF-modulated apoptotic cascade (Lu et al., 2006). In the present work, we present our results of studies of the changes of NGF expression after propofol anesthesia. The effect of propofol on NGF mRNA was region-specific. NGF and BDNF mRNA expression is activity-dependent and the balance between the activities of the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems controls the physiological level of NGF mRNA in neurons in vitro and in vivo (Zafra et al., 1991). According to our results, it can be assumed that the functional state of the cortex was influenced to a greater extent by propofol anesthesia than the functional state of the thalamus. This assumption is in agreement with the finding that propofol suppresses field potentials in the rat cortex to a greater extent than in the thalamus (Angel and LeBeau, 1992). Another explanation of the results could be that propofol increases the half-life of the unstable NGF mRNA in a region-specific manner.

Decreased levels of NGF protein were detected in both the cortex and the thalamus of P7 rats and they were more pronounced in the cortex. The changes in the expression profiles of mRNA and mature neurotrophin (NGF in our study) may have the same profile, but it is not necessarily the case. Mature neurotrophins are formed by proteolytic cleavage of their precursors (proneurotrophines) by intracellular and extracellular processing. Thus, the enzymes that process proneurotrophins assume an important role in maintenance of the physiological level of mature neurotrophins. Data from our study suggested that propofol may influence NGF production at the level of proNGF processing (at least in the thalamus), and additional analysis will elucidate this issue.

The next step in our experiments was to examine the relationship between the decreased level of NGF and the expression of phosphorylated (active) Akt. The binding of neurotrophins to Trk receptors leads to dimerization and trans-phosphorylation of the receptors, the recruitment of different adaptors and enzymes and the activation of several signaling pathways, including the PI3K-Akt pathway (Arevalo and Wu, 2006). Our experiments showed that the expression of phosphorylated Akt was decreased after the propofol treatment in both brain structures. The decrease was first observed in the thalamus and then in the cortex despite the similar patterns of change in NGF expression in both structures. These results were expected if we take into consideration the compensatory effects of the different neurotrophins in the central nervous system. The importance of active Akt for neuronal survival is well documented (Crowder and Freeman, 1998; Dudek et al., 1997). How Akt regulates the activity of its targets, as well as the mechanisms whereby PI-3K regulates Akt activity was extensively discussed in the review by Vanhaesebroeck and Alessi (2000). It was recently shown that Trk phosphorylation is not sufficient to prevent apoptosis and that the critical balancing point in neurotrophin-dependent survival vs. death occurs between Trk activation and phosphorylation of downstream targets, specifically of Akt (Volosin et al., 2006).

Pioneering studies from Eugene Johnson’s group performed in the late 1980s showed that apoptosis resulting from NGF withdrawal required both transcription and translation to occur (Martin et al., 1988). The authors showed that NGF represses a cascade of protein synthesis from de novo synthesized mRNA that leads to cell death. Thus, alterations in gene expression are the first changes observed in neurons deprived of survival factors.

The next goal of our investigation was to examine whether the decrease in NGF expression was accompanied by an increase in TNFα expression, an established inducer of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway (Baud and Karin, 2001). Indeed, we observed increased expression of TNFα mRNA after the propofol treatment in both the cortex and thalamus. This was followed by a prolonged increase in soluble TNFα protein expression. This form of TNFα protein is obtained by the proteolytic cleavage of a 26 kDa membrane-bound precursor protein by the TNFα-converting enzyme (Wajant et al., 2003). Hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that propofol treatment induces changes in enzyme activity.

The involvement of TNFα in the regulation of developmental programmed cell death has been described (Barker et al., 2001; Mao et al., 2006). Although it can trigger apoptosis through more than one pathway, the most widely accepted pathway involves the TNF receptor-associated death domain protein (TRADD), Fas-associating protein with a death domain (FADD) and the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3 (Baud and Karin, 2001; Chen and Goeddel, 2002). In order to examine the potential apoptotic events associated with increased expression of TNFα, we analyzed the changes in caspase-8 mRNA expression and observed its significant increase 8, 16 and 24 h after the propofol treatment in both the cortex and the thalamus. Although we did not examine caspase-8 at the protein level, an increase in caspase-8 mRNA has been shown to correlate with its protein level (Zhang et al., 2003).

Caspase-3 is the major effector protease in apoptosis triggered by various stimuli. We examined whether the described propofol-induced changes converged on caspase-3 activation. Our experiments showed that propofol anesthesia increased the level of active caspase-3 in the cortex and the thalamus of P7 rats 16 and 24 h after the treatment. An increase in active caspase-3 expression 4 h after the propofol injection was observed in the thalamus but not in the cortex. This could be due to a rapid turnover rate of caspase-3 in the cortex. It could also point to early apoptotic events specific to the thalamus.

To confirm the neurotoxicity of propofol we undertook imunohistochemical studies. Degenerating cells were identified with Fluoro-Jade B, a second-generation fluorescein derivative (Schmued and Hopkins, 2000). An increased number of disseminated Fluoro-Jade B positive cells was observed throughout the cortex (especially in the posterior cingulated/retrosplenial cortex) and in thalamic nuclei (especially in the lateral dorsalis) of P7 rats 24 h after the propofol treatment. Considering that the level of active caspase-3 was increased, we presumed that these cells largely died by apoptotic mechanisms.

To conclude, we report for the first time that short-term propofol anesthesia induces a decrease in NGF expression that is accompanied by an increase in TNFα expression in the cortex and in the thalamus of P7 rats. The observed changes were followed by a decrease in phosphorylated Akt expression, caspase-3 activation and cell death and all are in agreement with the report of Cattano et al. (2008). Furthermore, our findings are in accord with the data describing the anesthesia-induced damage in the most vulnerable regions of the developing brain – the anterior thalamus and cerebral cortex (Jevtović-Todorović et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2006). In contrast to the papers that have described the effects of different combinations of anesthetics when applied for several hours (that thereby disturb tonic neuronal activity and continuous neuronal signaling), we showed that the cortex and the thalamus of P7 rats were very sensitive to the effects of short-term propofol anesthesia. Thus, aside from the duration of exposure to general anesthesia, the molecular mechanisms of propofol action that contribute to its apoptogenic action should be taken into consideration (Grasshoff and Gillessen, 2005; Kozinn et al., 2006). Our preliminary results indicate that propofol induces changes in the expression of proneurotrophins, potent p75NTR ligands, whose signaling pathway(s) are under investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants (143004B and 143009B) from the Ministry of Sciences and Technological Development, Republic of Serbia and the John E. Fogarty International Center at the NIH Award GC11479-128322 (to S.R).

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DISC

death-inducing signaling complex

- FADD

Fas-associating protein with a death domain

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GAPDH

glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IAP

inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- P7

7-day-old

- p75NTR

p75 neurotrophin receptor

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- RT

reverse transcription

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRADD

TNF receptor-associated death domain protein

- Trk

tropomyosin-related kinase

References

- Allegaert K, Peeters MY, Veresselt R, Tibboel D, Naulaers G, de Hoon JN, Knibbe CA. Inter-individual variability in propofol pharmacokinetics in preterm and term neonates. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:864–870. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel A, LeBeau F. A comparison of the effects of propofol with other anaesthetic agents on the centripetal transmission of sensory information. Gen Pharmacol. 1992;23:945–963. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(92)90273-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo JC, Wu SH. Neurotrophin signaling: many exciting surprises. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1523–1537. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker V, Middleton G, Davey F, Davies AM. TNFα contributes to the death of NGF-dependent neurons during development. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1194–1198. doi: 10.1038/nn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud V, Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin JE, Constantin JM, Gindre G. Laboratory animal anaesthesia: influence of anaesthetic protocols on experimental models. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2004;23:811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Barde YA. Neurotrophins: key regulators of cell fate and cell shape in the vertebrate nervous system. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2919–2937. doi: 10.1101/gad.841400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattano D, Young C, Straiko MM, Olney JW. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1712–1714. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172ba0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Goeddel D. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder RJ, Freeman RS. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt protein kinase are necessary and sufficient for the survival of nerve growth factor dependent sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2933–2943. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02933.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, Birnbaum MJ, Yao R, Cooper GM, Segal RA, Kaplan DR, Greenberg ME. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasshoff C, Gillessen T. Effects of propofol on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated calcium increase in cultured rat cerebrocortical neurons. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22:467–470. doi: 10.1017/s0265021505000803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Briem T, Dzietko M, Sifringer M, Voss A, Rzeski W, Zdzisinska B, Thor F, Heumann R, Stepulak A, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Mechanisms leading to disseminated apoptosis following NMDA receptor blockade in the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vockler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtović-Todorović V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozinn J, Mao L, Arora A, Yang L, Fibuch EE, Wang JQ. Inhibition of glutamatergic activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases in hippocampal neurons by the intravenous anesthetic propofol. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LX, Yon JH, Carter LB, Jevtović-Todorović V. General anesthesia activates BDNF-dependent neuroapoptosis in the developing rat brain. Apotosis. 2006;11:1603–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8762-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao M, Hua Y, Jiang X, Li L, Zhang L, Mu D. Expression of tumor necrosis factor α and neuronal apoptosis in the developing rat brain after neonatal stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2006;403:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Schmidt RE, DiStefano PS, Lowry OH, Carter JG, Johnson EM., Jr Inhibitors of protein synthesis and RNA synthesis prevent neuronal death caused by nerve growth factor deprivation. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:829–844. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Farber NB, Wozniak DF, Jevtović-Todorović V, Ikonomidou C. Environmental agents that have the potential to trigger massive apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:383–388. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regula KM, Kirshenbaum LA. Apoptosis of ventricular myocytes: a means to an end. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Barker PA. Neurotrophin signaling through the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:203–233. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 2000;874:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanic N, Perovic M, Mladenovic A, Ruzdijic S, Kanazir S. Effects of aging, dietary restriction and glucocorticoid treatment on housekeeping gene expression in rat cortex and hippocampus-evaluation by real time RT-PCR. J Mol Neurosci. 2007;32:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapani G, Altomare C, Sanna E, Biggio G, Liso G. Propofol in anesthesia. Mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, and drug delivery. Curr Med Chem. 2000;7:249–271. doi: 10.2174/0929867003375335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck B, Alessi DR. The PI3K-PDK1 connection: more than just a road to PKB. Biochem J. 2000;346:561–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venters HD, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. A new concept in neurodegeneration: TNFa is a silencer of survival signals. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volosin M, Song W, Almeida RD, Kaplan DR, Hempstead BL, Friedman WJ. Interaction of survival and death signaling in basal forebrain neurons: roles of neurotrophins and proneurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7756–7766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1560-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajant H, Pfizenmaier K, Scheurich P. Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:45–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Slikker W. Strategies and experimental models for evaluating anesthetics: effects on the developing nervous system. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1643–1658. doi: 10.1213/ane.ob013e3181732c01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrin P. The induction dose of propofol in infants 1–6 months of age and in children 10–16 years of age. Anesthesiology. 1991;74:455–458. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H, Anderson WD, Cheng T, Riabowol KT. Monitoring mRNA expression by polymerase chain reaction: the “primer-dropping” method. Anal Biochem. 1994;223:251–258. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooltorton E. Propofol contraindicated for sedation of pediatric intensive care patients. CMAJ. 2002;167:507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev AG, Faden AI. Sequential expression of c-fos protooncogene, TNF-alpha, and dynorphin genes in spinal cord following experimental traumatic injury. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1994;23:179–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02815410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon JH, Daniel-Johnson J, Carter LB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Anesthesia induces neuronal cell death in the developing rat brain via the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Neuroscience. 2005;135:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafra F, Castren E, Thoenen H, Lindholm D. Interplay between glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid transmitter systems in the physiological regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and nerve growth factor synthesis in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Graham SH, Kochanek PM, Marion DW, Nathaniel PD, Watkins SC, Clark SB. Caspase-8 expression and proteolysis in human brain after severe head injury. FASEB J. 2003;17:1367–1369. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1067fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]