Abstract

Scope

This study investigated the in vivo and in vitro activity of α-mangostin (α-MG), the most abundant xanthone in mangosteen pericarp, on HT-29 cell tumorigenicity, proliferation, and several markers of tumor cell activity, as well as the profile and amounts of xanthones in serum, tumor, liver, and feces.

Methods and results

Balb/c nu/nu mice were fed either control diet or diet containing 900 mg α-MG/kg. After 1 week of acclimation to diet, mice were injected subcutaneously with HT-29 cells and fed the same diets ad libitum for an additional 2 or 4 weeks. After 2 and 4 weeks, tumor mass and the concentrations of BcL-2 and β-catenin in tumors of mice fed diet with α-MG were significantly less than in mice fed control diet. Xanthones and their metabolites were identified in serum, tumor, liver, and feces. In vitro treatment of HT-29 cells with α-MG also inhibited cell proliferation and decreased expression of BcL-2 and β-catenin.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate that the anti-neoplastic effect of dietary α-MG is associated with the presence of xanthones in the tumor tissue. Further investigation of the impact of beverages and food products containing xanthones on the prevention of colon cancer or as complementary therapy is merited.

Keywords: α-Mangostin, BcL-2 protein, β-Catenin protein, Tumor mass, Xenograft

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer is estimated to account for approximately 10% of all global cancers and cancer deaths [1]. Rates of colon cancer in affluent countries are markedly greater than in developing countries and the risk for Asians and Africans generally increases after immigrating to North America. Epidemiological, clinical, and experimental evidence has shown that dietary patterns, foods, and some dietary compounds are closely associated with the risk of colon cancer [1]. Chronic inflammation in the colon is also associated with an increased risk of cancer [2]. As many dietary polyphenols exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic activities [3], diet-based strategies to minimize colonic inflammation are expected to reduce the risk of colon cancer.

Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen; Clusiaceae) is a tropical fruit native to Southeast Asia that is often referred to as “the queen of fruits”. Products containing mangosteen fruits represented the sixth highest selling single-herb dietary supplement in U.S, in 2008 with sales exceeding $200 million [4]. The pericarp of mangosteen contains a family of polyphenols referred to as xanthones that are characterized by the presence of one or more prenyl and hydroxy groups in their tricyclic ring system [5]. Reported in vitro activities of the mangosteen xanthones have provided the basis for the aggressive marketing of the diverse health benefits of mangosteen-containing products, despite the limited number of in vivo studies investigating such claims [5,6]. The proposed health-promoting effects of mangosteen necessitate the delivery and uptake of the xanthones or their bioactive metabolites to target tissues. We previously reported that (i) α- and γ-MG in mangosteen pericarp are stable during simulated gastric and small intestinal digestion, (ii) α-MG is taken up by differentiated cultures of Caco-2 human intestinal cells in a dose-dependent manner and partially converted to phase 2 metabolites, and (iii) both free and conjugated forms of α-MG are transported across the basolateral membrane of Caco-2 cells, suggesting that this compound and its phase 2 metabolites are bioavailable [7]. We recently confirmed this possibility, since xanthones in a 100% mangosteen fruit juice product were found to be absorbed [8].

Investigation of the bioavailability and anti-cancer efficacy of mangosteen xanthones in preclinical animal models remains quite limited. Of particular interest is a report that feeding Balb/c mice, a semi-purified diet containing 2.5 or 5.0 g xanthones/kg diet significantly decreased tumor mass and metastasis of injected breast cancer cells when compared to mice fed the control diet [9]. Similarly, administration of as little as 200 and 500 mg “crude preparation” of α-mangostin (α-MG) per kg diet significantly inhibited the number of aberrant crypt foci, as well as decreasing both dysplastic foci and accumulation of β-catenin, in response to dimethylhydrazine [10]. The present study was designed to investigate the anti-tumorigenicity of ingested α-MG in athymic nude mice injected with human HT-29 colonic adenocarcinoma cells. To correlate the anti-tumorigenic effects with key mechanisms associated with colon carcinogenesis, the effect of α-MG on the proliferation and expression of the pro-apoptotic marker B-cell lymphoma-2 (BcL-2) and the promitogenic transcription factor β-catenin also were tested with cultured HT-29 cells. Finally, xanthones in serum, tumor, liver, and feces were determined to examine if the observed anti-tumorigenic activity was correlated with the presence of ingested xanthones in tissues.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and supplies

α-MG, β-mangostin (β-MG), and γ-mangostins (γ-MG), garcinones D and E, 8-deoxygartanin, gartanin, and 9-hydroxycalabaxanthone were purified (≥98% as assessed by NMR spectroscopy and ESIMS), as described elsewhere [11, 12]. BcL-2 and β-catenin assay kits were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY, USA). All other reagents and supplies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Gibco (Invitrogen, CA, USA), Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), and Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA).

2.2 Colonic cell line

The HT-29 human adenocarcinoma colon cell line (passage 135) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and used at passages 140–148. Cells were maintained in McCoy’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (final concentrations of 100 U of penicillin and 100 µg streptomycin per mL) and 0.2% fungizone (final concentration of 25 ng/mL) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. Fresh medium was provided every second day.

2.3 In vivo study

2.3.1 Animal model

Animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Protocol # 2011A00000006. Female athymic Balb/c nu/nu mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Balb/c nu/nu mice were received at 4 weeks of age. Animals were acclimated for 4 days (n = 3 per cage) located in a controlled humidity (50 ± 10%), light (12 h light/dark cycle), and temperature (23 ± 2°C) room. Mice were given free access to AIN-93G diet (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and sterile de-ionized water.

2.3.2 Diet

AIN-93G diet [13] without and with 900 mg/kg α-MG was prepared by Research Diet, Inc and sterilized by γ-radiation. This dose is well below the 2500 or 5000 mg of a mixture of α- and γ-mangostin/kg diet that decreased tumor mass and metastasis of injected breast cancer cells in BALB/c mice [9]. Diets were extracted to determine the actual concentration of α-MG as described below. Analysis revealed that the total xanthone content of the test diet was 901 ± 36 mg/kg with α-MG accounting for 94% of the total xanthone content (Table 1). Structures of the detected dietary xanthones in this study are shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1. The amounts and profile of xanthones in the test diet remained stable throughout the study (data not shown).

Table 1.

Xanthone composition in test diet

| Xanthones | AIN-93G + α-mangostin mg/kg diet |

Percent total |

|---|---|---|

| Garcinone C | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Garcinone D | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Garcinone E | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 8-Deoxygartanin | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Gartanin | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 0.6 |

| α-Mangostin | 845.2 ± 36.7 | 93.8 |

| β-Mangostin | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 |

| γ-Mangostin | 6.2 0.3 | 0.7 |

| 9-Hydroxycalabaxanthone | 16.2 ± 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Unknown xanthonesa) | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Total xanthones | 901 ± 36 | 100 |

Concentration estimated as α-MG equivalents.

Data are mean ± SD, n = 4.

2.3.3 Experimental design

Mice were assigned randomly to one of two dietary groups (n = 24/group) fed either the control diet or diet with α-MG. Food intake, general appearance/behavior, and body weight were monitored after 3 and 7 days to determine if dietary α-MG affected consumption, activity, and weight.

Cultures of HT-29 colon cells (passage 141) were grown in T75 flasks to 70–80% confluence. Monolayers were washed twice with warm sterile PBS, released from the surface with trypsin-EDTA, collected by centrifugation, and suspended in McCoy’s medium with matrigel (1:1, v/v) [14] to 2.5 × 106 cells/mL. Mice (n = 18) in each dietary group were injected subcutaneously in each flank with 200 µL vehicle containing 5 × 105 HT-29 colonic cells. The remaining six nontumor-bearing animals in the control and α-MG dietary groups were injected with vehicle only. Mice continued to be fed either the respective control or α-MG diets throughout the study.

The behavior of all mice was monitored daily by a veterinarian and animals were weighed weekly. Maximal longitudinal (x) and maximal transverse (y) diameters were measured weekly with a Vernier sliding jaw caliper (Ohaus Scale Corp., Florham Park, NJ, USA) by the same observer to estimate tumor volume [15]. Two weeks after injection of HT-29 cells, 12 tumor-bearing mice from both the control and test diet groups were sacrificed by inhalation of CO2 and cardiac puncture after fasting for 10 h (food removed from cages at 10 pm). Tumor tissue and liver were excised, rinsed in cold saline, weighed, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storing at −80°C. Clotted blood was centrifuged (800 × g, 10 min, 4°C) to isolate serum and stored at −80°C. Fecal pellets were also collected daily, weighed, and stored in screw-capped polypropylene tubes at −80°C. The remaining non-tumor bearing and tumor-bearing mice (n = 6 each for both dietary groups) were continued to be fed the assigned diet until 4 weeks after injection when the xenograft volume in mice fed the control diet was <250 mm2. Fasted mice were killed and tissues were collected as above. Feces also were collected daily from nontumor bearing mice and tumor bearing mice 21–28 days after inoculation with HT-29 cells.

2.3.4 Xanthone analysis

Samples of liver, tumor, and pooled feces were weighed and transferred to a glass hand-held homogenizer. Ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) was added and samples (approximately 50 mg sample/mL) were disrupted manually. An aliquot of homogenate (2 mL) was transferred to a 5 mL polypropylene tube and 2 mL ACN were added. Samples were mixed by vortexing for 1 min and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Each supernatant was transferred to a clean glass tube and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. The film was re-solubilized in sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and incubated at 37°C in the absence or presence of glucuronidase/sulfatase mixture from Helix pomatia (150 units/mg tissue) for 2 h to hydrolyze xanthone conjugates. This was followed by SPE using C18 cartridges [16] with the eluate collected for HPLC-DAD analysis. Serum (100 µL) was mixed 1:1 with sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), incubated with or without glucuronidase/sulfatase enzymes (160 units: 100 µL serum), and further processed as above. Extracts were analyzed using an HPLC system consisting of a Waters 2695 separation module with a 2996 diode-array detector (DAD) controlled by an Empower 2 workstation (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Xanthones were separated as described elsewhere [11]. Garcinones D and E, α-, β-, and γ-mangostins, 8-deoxygartanin, gartanin, and 9-hydroxycalabaxanthone were identified by comparison of their retention time and UV spectrum with purified standards (>98% purity as determined by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy and ESIMS) [11,12]. Concentrations were determined by comparison with known quantities of pure compounds prepared gravimetrically. The five-point calibration curves were linear with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.998. The LOD of xanthones was 12.2 nmol/L (S/N ratio = 3). Peaks containing compounds with xanthone-like absorption spectra were identified tentatively as unknown xanthones and their concentrations were estimated as equivalents of α-MG.

As the above method lacked sufficient sensitivity to detect xanthones other than α-MG in serum, sera were selected randomly for analysis by HPLC-MS to determine if other xanthones were present. Analysis was performed on a Micromass LC-Tof™ II (Micromass, Wythenshawe, UK) mass spectrometer equipped with an orthogonal electrospray source (Z-spray) operated in the positive-ion mode. The mobile phase flow rate was maintained at 0.75 mL/min and was split postcolumn using a microsplitter valve (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA, USA) to 20 µL/min for introduction to the ESI source. Sodium iodide was used for mass calibration for a calibration range of m/z 100–2000. Optimal ESI conditions were: capillary voltage 3000 V; source temperature 110°C; and cone voltage of 55 V. The ESI gas was nitrogen. Q1 was set to optimally pass ions from m/z 100–2000, and all ions transmitted into the pusher region of the TOF analyzer were scanned with a 1 s integration time. Data were acquired in continuum mode during the HPLC run. The same approach was used to confirm the identity of assigned peaks of xanthones in extracts from the tumor tissue and the liver.

2.3.5 Tumor tissue markers

Tumor tissue (20–100 mg) was disrupted by homogenizing in 2 mL of lysis solution containing PMSF (1 mM) and protease inhibitor cocktail (2–10 mL). Homogenates were vigorously vortexed for 15 s and centrifuged (16 000 × g, 4°C, 15 min). Aliquots of supernatant were analyzed for β-catenin and BcL-2 by ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions for the kits (Enzo Life Sciences).

2.4 In vitro study

2.4.1 α-MG and cell viability

HT-29 colon cells suspended in McCoy’s medium containing 10% FBS were transferred to 12-well dishes (1.25 × 105 cells/well). When monolayers were approximately 50% confluent, fresh medium containing α-MG (0–200 µmol/L; purity ≥95% pure) that had been solubilized in Tween-40 was added to wells and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air: 5% CO2. After 24 h, the viability of HT-29 cells was assessed using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H–tetrazolium (MTT) bromide assay [17]. Briefly, following the incubation of cells with either Tween-40 only as control or Tween-40 containing α-MG, 50 µL MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) were added to each well and the dish was incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Spent medium was removed and 200 µL DMSO were added to each well to dissolve the purple formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Synergy HT microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instrument, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was expressed as the percentage of MTT absorbance compared to control cultures.

2.4.2 Effect of α-MG on BcL-2, and β-catenin content in HT-29 cells

HT-29 cells were seeded in 6-well dishes (2 × 105 cells/well). At 70% confluence, monolayers were incubated in basal McCoy’s medium without and with α-mangostin (6 and 12 µmol/L) for 24 h. Monolayers were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and cells collected by centrifugation (800 × g, 4°C, 10 min). The cell pellet was disrupted in 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer and the quantity of BcL-2 and β-catenin determined by ELISA as for the tumor tissue (Enzo Life Sciences).

2.5 Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-test (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to determine significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatment groups for body weight, food consumption, and tissue and fecal xanthones in the various treatment groups. Two-way ANOVA was used to investigate the effect of dietary treatment and duration of treatment on tumor volume. Tumor mass, BcL-2, and β-catenin content in tumors, and in vitro effects of α-MG on proliferation and other markers of HT-29 cells were compared among control and treatment groups performed by Welch’s unpaired Student’s t-test due to unequal sample size and unequal variance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Graph-Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Effect of dietary α-MG on food intake and body weight

Food intake and body weight were not significantly altered by the inclusion of 845 mg/kg α-MG (901 mg total xanthones/kg) in the diet or by the presence of the HT-29 xenograft (Supporting Information Table S1) during the study. The mean daily intake of α-MG for the nontumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice fed the α-MG diet for the 5-week feeding period was 3.25 ± 0.2 and 3.15 ± 0.2g, respectively.

3.2 Anti-tumorigenic effect of dietary α-MG

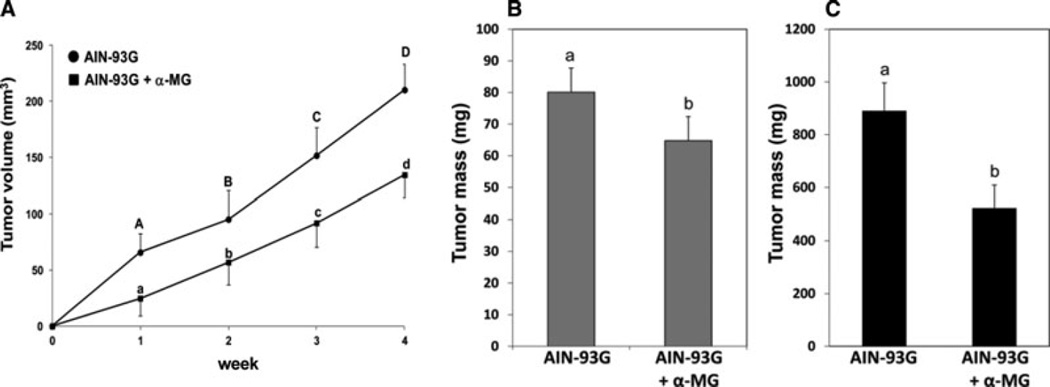

HT-29 cells injected in the bilateral flanks engrafted with 100% efficiency in both the control and in the α-MG dietary groups. Tumors in mice fed the control diet reached a maximal average volume of 118 and 235 mm2 at 2 and 4 weeks after injection, respectively (Fig. 1A). Tumor volumes in mice fed diet with α-MG were 41% and 36% less than those in mice fed the diet without α-MG at 2 and 4 weeks after the injection of HT-29 cells, respectively (Fig. 1A). Similarly, tumor masses were 27 and 41% less in mice fed the diet with α-MG compared to the control diet at 2 weeks (Fig. 1B) and 4 weeks (Fig. 1C), respectively, after injection of HT-29 cells.

Figure 1.

Dietary α-MG decreases growth of HT-29 tumor in mice. Panel A: Tumor growth after injection of HT-29 colonic cells as assessed by computed volume. Data are means ± SD; n = 18 per dietary group for weeks 1 and 2 and 6 per dietary group for weeks 3 and 4. Tumor mass was measured in mice fed diet with α-MG compared to mice fed control diet at 2 weeks (panel B) and 4 weeks (panel C) after xenograft transplantation. Data are means ± SD; n = 12 and six mice at 2 and 4 weeks after xenograft transplantation, respectively. Presence of different letters above error bars indicates significant differences between means at p < 0.01.

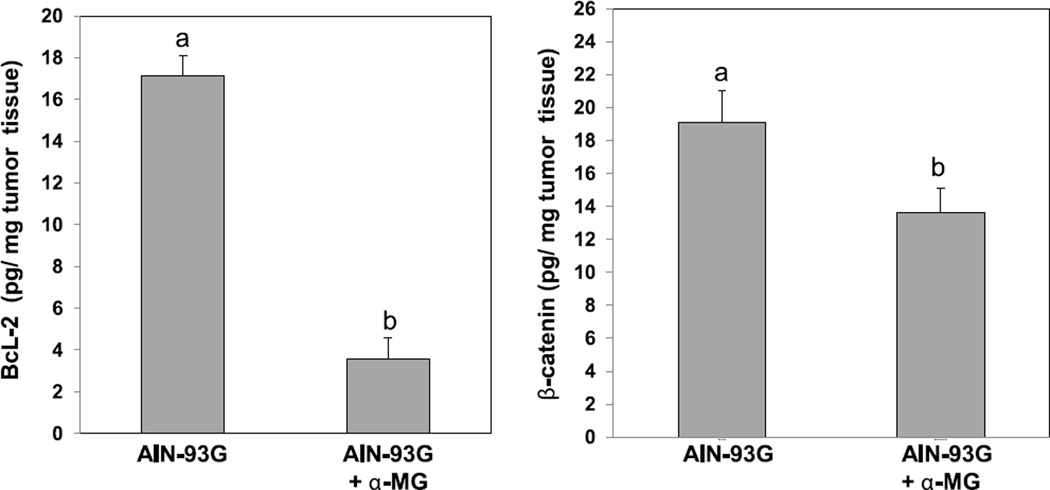

3.3 Biomarkers of anti-tumorigenic activity

α-MG, like many other phytochemicals has been suggested to affect processes associated with cancer [18,19]. To investigate biomarkers of apoptosis and proliferation contributing to xenograft tumor progression, we quantified anti-apoptotic BcL-2 and mitogenic β-catenin in tissue homogenates by ELISA (Fig. 2). The concentrations of both proteins were significantly (p < 0.001) lower in tumors from mice fed diet with α-MG (3.9 ± 0.5 and 11.2 ± 0.7 pg/mg protein, respectively) compared to the control diet (17.2 ±0.8 and 19.1 ± 1.9 pg/mg protein, respectively).

Figure 2.

BcL-2 and β-catenin protein were significantly reduced in HT-29 tumors from mice fed diet with α-MG compared to control diet at 4 weeks after injection of cells. Data are means ± SD, n = 8. Different letters above bars indicates significant differences (p < 0.001).

3.4 Tissue xanthones

Initial analysis of serum from nontumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice fed diet with α-MG for 5 weeks indicated that only a trace amount of the xanthone (15 ± 1 ng/mL) was present. However, incubation of serum with glucuronidase/sulfatase enzyme mixture from H. pomatia increased the amount of α-MG in serum by approximately two orders of magnitude, revealing extensive conjugation of the xanthone. The concentration of total α-MG in serum of mice with tumors 4 weeks after injection of cells was significantly greater than that in nontumor-bearing mice (2.5 ± 0.2 µg/mL versus 1.9 ± 0.3 µg/mL, respectively; p < 0.05). The concentration of conjugated α-MG in serum in mice bearing tumors for 4 weeks also was significantly greater than that in mice with tumors for 2 weeks (1.0 ± 0.1 µg/mL;p < 0.001). Since α-MG was the only xanthone detected in enzyme-treated serum using HPLC-DAD, the serum also was analyzed by HPLC-MS to provide greater sensitivity. Low concentrations of other xanthones including garcinones, gartanins, 9-hydroxycalabaxanthone, and β- and γ-MG were identified in serum (Supporting Information Fig. S2). These data collectively show that the dietary xanthones were absorbed.

With the exception of garcinones C and D, xanthones present in the diet were detected in tumors at both 2 weeks and 4 weeks (Table 2). Xanthones were not detected in tumors from animals fed the control diet (data not shown). The concentration of total xanthones in tumors were significantly greater in tumors at 4 weeks after injection of HT-29 cells (9.5 ± 0.2 µg/g) compared to that after 2 weeks (3.3 ± 0.2 µg/g) (p < 0.001). Both free and conjugated α-MGs were present in tumor tissue at concentrations of 1.4 ± 0.03 (60% conjugated) and 3.6 ± 0.1 (52% conjugated) at 2 and 4 weeks postinjection, respectively. Surprisingly, β-MG was tentatively identified on basis of its retention time and spectrum as the most abundant xanthone in the tumor tissue, representing 41 and 45% of total xanthones in tumors after 2 and 4 weeks, respectively, after injection of HT-29 cells. Although phase II conjugates of β-MG were not detected in tumors at 2 weeks, such conjugates accounted for 40% of tumor β-MG at 4 weeks. Together, the above data demonstrate that the presence of xanthones in tumors was correlated with the impaired growth of the HT-29 tumors.

Table 2.

Xanthone profile in tumor tissue at 2 and 4 weeks after injection of HT-29 cells into mice fed diet containing 901 mg/kg xanthones

| Xanthones | Tumor at 2 weeks µg/g |

Tumor at 4 weeks µg/g |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Conjugates | Free | Conjugates | |

| Garcinone E | 0.09 ± 0.03a) | nd | 0.14 ± 0.05a) | nd |

| 8-Deoxygartanin | 0.22 ± 0.01b) | nd | 0.54 ± 0.04a) | nd |

| Gartanin | 0.11 ± 0.05b) | nd | 0.32 ± 0.12a) | nd |

| α-Mangostin | 0.51 ± 0.02b) | 0.76 ± 0.03c) | 1.71 ± 0.06a) | 1.87 ± 0.06a) |

| β-Mangostin | 1.54 ± 0.16b) | nd | 2.68 ± 0.17a) | 1.83 ± 0.17b) |

| γ-Mangostin | 0.12 ± 0.02b) | nd | 0.23 ± 0.03a) | nd |

| 9-Hydroxycalabaxanthone | 0.22 ± 0.09a) | nd | 0.32 ± 0.11a) | nd |

| Unknown xanthonesa) | 0.15 ± 0.02b) | nd | 0.21 ± 0.02a) | nd |

| Total xanthones | 3.0 ± 0.2b) | 0.8 ± 0.0c) | 6.2 ± 0.2a) | 3.7 ± 0.2b) |

Concentration estimated as α-MG equivalents.

Data are mean ± SD. n = 6 and 8 for tumors from mice at 2 and 4 weeks after injection of HT-29 cells, respectively. Different letters as superscripts in a row indicate mean concentrations are significantly different (p < 0.01); nd = not detected.

The xanthone contents in the livers from nontumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice fed diet with α-MG were also analyzed (Supporting Information Table S2). Interestingly, hepatic xanthone content was 78% greater in tumor bearing mice after 4 weeks than in age-matched mice lacking tumors (40.7 ± 2.7 µg/g versus 23.0 ± 1.3 µg/g, respectively; p < 0.001). Hepatic xanthone content in mice bearing tumors for 2 weeks also was greater than in liver of nontumor-bearing mice 4 weeks after time of injection (27.0 ± 1.2 µg/g versus 23.0 ±1.3 µg/g, respectively; p < 0.05). As observed with tumor tissue, a xanthone tentatively identified as β-MG was the most abundant xanthone (approx. 85% of the total xanthones) in the liver of control- and tumor-bearing mice. Phase II conjugates of xanthones represented less than 6% of the total xanthones in the liver in contrast to their relative abundance in tumor tissue.

Fecal pellets were collected from tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice fed diet with α-mangostin to estimate daily excretion of xanthones. All xanthones present in the diet were detected in feces (Supporting Information Table S3). Daily fecal excretion of xanthones was significantly (p < 0.0001) greater in control mice than in mice bearing the tumor (78 ± 1.2% versus 50 ± 2.5% of daily intake, respectively). The relative amounts of the various xanthones in feces from control animals were similar to that in the diet with the exception of garcinone D that was enriched in feces (Table 1). In contrast, the relative amounts of β-MG and γ-MG, as well as garcinone D, in feces shed by tumor bearing mice were significantly (p < 0.001) greater than in the diet, whereas the relative amount of α-MG was significantly less (p < 0.001) than in the diet (Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S3). Phase II conjugates of α- and β-MG were present in feces from both groups of mice.

3.5 In vitro effects of α-MG on proliferation, pro-apoptotic, and anti-mitogenic markers in HT-29 colonic cells

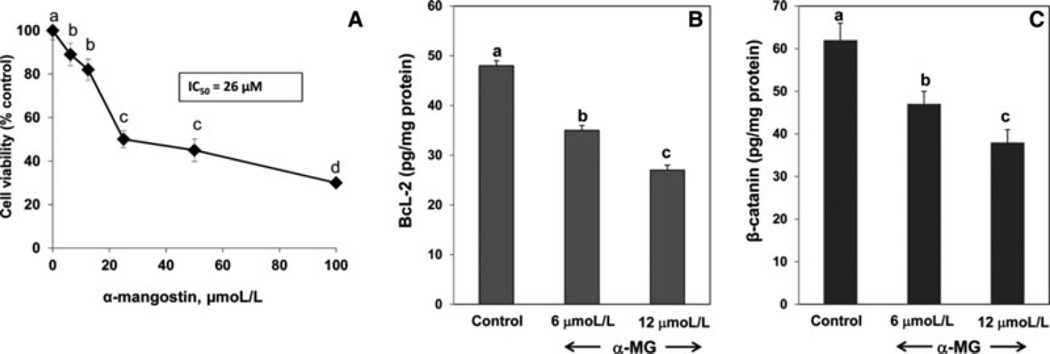

To determine the direct effects of α-MG on proliferation of HT-29 colon cells, sub-confluent cultures of cells were incubated with 6–100 µmol/L α-MG for 24 h. Reduction of MTT to its formazan derivative was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 26 µmol/L α-MG (Fig. 3A). Incubation of preconfluent monolayers of HT-29 cells with 6 µmol/L α-MG significantly decreased the amounts of BcL-2 by 27 ± 3% (p < 0.01) and β-catenin by 24 ± 2% (p < 0.01), respectively, as compared to cultures incubated with vehicle only (Fig. 3B and C). When medium concentration of α-MG was increased to 12 µmol/L, cellular content of BcL-2 and β-catenin in cells was 44 ± 4% (p < 0.001) and 39 ± 3% (p < 0.001), respectively, less than those in control cultures.

Figure 3.

α-MG decreases viability (panel A) and concentrations of BcL-2 (panel B) and β-catenin (panel C) in preconfluent cultures of HT-29 cells in vitro. Data are means ± SD, n = 6. The presence of different letters above the error bars indicates significant differences (p < 0.01).

4 Discussion

Our results clearly demonstrate anti-tumorgenic activity of α-MG, the most abundant xanthone in the pericarp of the tropical fruit mangosteen (G. mangostana L.). Consumption of a semi-purified diet with 845 mg/kg α-MG (901 mg/kg xanthones) attenuated the growth of the HT-29 human colonic cell xenograft without adversely affecting food intake or body weight. The reduced tumor mass in mice fed the diet containing α-MG also had lower concentrations of the antiapoptotic protein, BcL-2, and β-catenin, the transcription factor essential for the expression of Wnt target genes such as c-myc, c-jun, and cyclin D1, compared to those in tumors in mice fed the control diet. Our observations with the murine model align well with several recent reports that α-MG administered by oral gavage (100mg/kg/5× per week), continuous subcutaneous administration using osmotic mini-pumps (0.036 mg/d) and direct intra-tumoral injection (0.024–3.0 mg 1×) decreased the growth of xenografts of murine prostate [20], murine mammary [21], and human COLO colonic cancer cells [22], respectively. Likewise, Nabandith et al. [9] reported that dietary administration of 500 mg/kg xanthones (78% α-MG, 16% γ-MG) to rats injected with dimethylhydrazine significantly inhibited the total number of aberrant crypt foci in the colon and decreased both dysplastic foci and β-catenin accumulation in the crypts.

We also observed that exposure of cultures of HT-29 cells to 6 and 12 µmol/L α-MG inhibited cell proliferation and decreased cellular BcL2 and β-catenin. Our in vitro results are similar to previous reports on the anti-proliferative [23, 24] and anti-apoptotic [25–27] activities of α- and γ-MG with various animal and human cancer cell lines. It is interesting that in vitro exposure of human DLD-1 colon cells to α-MG-induced apoptosis by decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential leading to the release of endonuclease-G responsible for caspase-independent apoptosis [26]. Recent reports further suggest that α-mangostin mediates its anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on cultured cells by inhibiting Akt, MAPK, NF-κB, and Wnt/cGMP signaling pathways [28–31].

Of particular interest is whether the observed antitumor activity of dietary α-MG and trace contaminants of other mangosteen xanthones was the result of the direct or indirect actions of one or more of these compounds. The possibility that xanthones directly inhibit tumor growth requires the delivery of these compounds or their metabolites to the tissue. The absorption, tissue distribution, and metabolism of xanthones have received minimal previous attention. Bumrungpert et al. [7] reported apical and trans-epithelial transfer of α-MG by differentiated monolayers of Caco-2 human intestinal cells. A portion of α-MG also was converted to glucuronidated/sulfated metabolites that effluxed across both the apical and basolateral membranes. Kondo et al. [32] reported the presence of free α-MG in plasma of human subjects (Cmax, 3.1 nmol/mL) after consuming a mangosteen juice blend containing 94 mg/mL α-MG. We subsequently examined the bioavailability of xanthones in human subjects ingesting 100% mangosteen juice (130 mg dose) co-administered with a breakfast meal [8]. As predicted from results with Caco-2 cells, both free xanthones and their phase 2 conjugates were present in serum and urine collected during 24-h period following consumption of the juice. Urinary xanthone content suggested absorption of a minimum of 2% of the ingested. Li et al. [33] reported an extremely low absorption of α-MG in rats following gastric administration of 20 mg/kg in water containing 2% ethanol plus 2% Tween-80.

The present results clearly show that dietary xanthones are bioavailable to athymic nude mice as evidenced by the presence of free and conjugated xanthones in serum, tumor, and liver of control- and tumor-bearing mice. Also, the concentrations of xanthones in these tissues increased with greater duration of consumption of the supplemented diet. It is interesting that the concentration of α-MG in serum and liver of mice-bearing tumors exceeded those in mice-lacking tumors, suggesting that the pathological condition affected absorption, metabolism, excretion, or some combination of these possibilities in tumor-bearing animals. Moreover, the relative amounts of the various xanthones in tumor, liver, and feces differed considerably from those in the diet. This was particularly notable for the greater concentration of β-MG compared to α-MG in the tumor and liver despite β-MG representing only 0.3% of total dietary xanthones. β-MG was also enriched in feces compared to diet. β-MG can be generated from α-MG by methylation of the 3-hydroxyl position of the B ring (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The likelihood of this biotransformation is supported by the presence of other phase II metabolites of xanthones in tumor, liver, and feces shed by the mice, as well as in human serum and urine [8]. Potential interconversions of free xanthones are outlined in Supporting Information Fig. S1. Many dietary polyphenols are metabolized to bioactive compounds by the gut micro-biota with the generated metabolites being absorbed and modulating cellular processes in target organs [34–36]. It is interesting that in vitro exposure of human DLD-1 colon cell induced apoptosis by decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential leading to the release of endonuclease-G responsible for caspase-independent apoptosis [26]. The amount of xanthones in feces supports the likelihood that the gut epithelium is exposed to relatively high concentrations of ingested xanthones. Of particular interest in this regard is the reported inhibitory activity of α-MG on inflammatory signaling cascades in several preclinical models [37,38]. The possible impact of α-MG on gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders in the gut warrants consideration.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that dietary α-MG inhibited the growth of HT-29 colonic cells in nude mice. The presence of xanthones in the tumor, serum, and liver shows that dietary α-MG was bioavailable and appears to be metabolized to other xanthones and their phase 2 conjugates. Studies to determine the activities of these xanthones and their metabolites within the colonic tumor cells have been initiated. We estimate that the dose of α-MG fed to mice in this study is 25–100-fold greater than that likely ingested by humans consuming commercial mangosteen beverages with recommended servings of 2–8 ounces daily. Critical assessment of health-promoting claims of such products in humans is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center/Molecular Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention Program and Food Innovation Center, The Ohio State University. The Thailand Research Fund (Grant DBG5280013) and the Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC), Commission for Higher Education, Ministry of Education, Thailand.

Abbreviations

- α-MG

α-mangostin

- BcL-2

B-cell lymphoma-2

- β-MG

β-mangostin

- γ-MG

γ-mangostin

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site

The authors have declared no conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent or reflect views of Comprehensive Cancer Center/Molecular Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention and Food Innovation Center, The Ohio State University.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl C, Hombach A, Kruis W. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2000;47:57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos S. Cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy: dietary polyphenols and signaling pathways. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:507–526. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloan EW. Getting ahead of the curve: phytochemicals. Nutraceutical World. 2010;13:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obolskiy D, Pischel I, Siriwatanametanon N, Heinrich M. Garcinia mangostana L: a phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother. Res. 2009;23:1047–1065. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin YW, Kinghorn AD. Structural characterization, biological effects, and synthetic studies on xanthones from mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana), a popular botanical dietary supplement. Mini-Rev. Organ. Chem. 2008;5:355–364. doi: 10.2174/157019308786242223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bumrungpert A, Kalpravidh RW, Suksamrarn S, Chaivisuthangkura A, et al. Bioaccessibility, biotransformation and transport of α-mangostin from Garcina mangostana (mangosteen) using simulated digestion and Caco-2 human intestinal cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009;53:S54–S61. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitchumroonchokchai C, Riedl KM, Suksumrarn S, Clinton SK, et al. Xanthones in mangosteen juice are absorbed and partially conjugated by healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2012;142:675–680. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.156992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi H, Shibata M, Shibata E, Morimoto J, et al. Panaxanthone isolated from pericarp of Garcinia mangostana L. suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of a mouse model of mammary cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2485–2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nabandith V, Suzuki M, Morika T, Kaneshiro T, et al. Inhibitory effects of crude α-mangostin, axanthone derivative, on two different categories of colon preneoplastic lesions induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine in the rat. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2004;5:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaivisuthangkura A, Malaikaew Y, Chaovanalikit A, Jaratrungtawee A, et al. Xanthone composition of Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) fruit hull. Chromatographia. 2009;69:315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung HA, Su BN, Keller WJ, Mehta RG, et al. Antioxidant xanthones from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:2077–2082. doi: 10.1021/jf052649z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC. AIN-93 purified diet for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993;123:1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen RL, Leppla D, Rokosz N, Wurster RD. Ma-trigel augments xenograft transplantation of meningioma cells into athymic mice. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:130–136. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrara E, Forssell-Aronsson E, Ahlman H, Bernhardt P. Specific growth rate versus doubling time for quantitative characterization of tumor growth rate. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3970–3975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh KR, Haak SJ, Bohn T, Tian Q, et al. Isoflavonoid glucosides are deconjugated and absorbed in the small intestine of human subjects with ileostomies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:1050–1056. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YS, Milner J. Dietary modulation of colon cancer risk. J. Nutr. 2007;137:2576S–2579S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2576S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan T, Ma Q, Guo K, Liu J, et al. Xanthones from mangosteen as natural chemopreventive agents: potential anticancer drugs. Curr. Mol. Med. 2011;11:666–677. doi: 10.2174/156652411797536679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JJ, Petiwala SM, Syed DN, Rasmussen JT, et al. α-Mangostin, a xanthone from mangosteen fruit, promotes cell cycle arrest in prostate cancer and decreases xenograft tumor growth. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:413–419. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata MA, Linuma M, Morimoto J, Kurose H, et al. α-Mangostin extracted from the pericarp of the mangos-teen (Garcinia mangostana Linn) reduces tumor growth and lymph node metastasis in an immunocompetent xenograft model of metastatic mammary cancer carrying a p53 mutation. BMC Med. 2011;9:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanapokasin R, Jarinthanan F, Jerusalmi A, Suksanrarn J, et al. Potential of xanthones from tropical fruit mangosteen as anti-cancer agents: capase-dependent apoptosis induction in vitro and in mice. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2011;17:2086–2095. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedro M, Cerqueira F, Sousa ME, Nascimento MS, et al. Xanthones as inhibitors of growth of human cancer cell lines and their effects on the proliferation of human lymphocytes in vitro. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:3725–3730. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han AR, Kim JA, Lantvit DD, Kardono Ls, et al. Cytotoxic xanthone constituents of the stem bark of Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:2028–2031. doi: 10.1021/np900517h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Ohguchi K, Ito T, et al. Xanthones induce cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in human colon cancer DLD-1 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:6064–6069. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa Y, Iinuma M, Naoe T, Nozawa Y, et al. Characterized mechanism of α-mangostin-induced cell death: capase-independent apoptosis with release of endonuclease-G from mitochondria and increased miR-143 expression in human colorectal cancer DLD-1 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:5620–5628. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang HF, Huang WT, Chen HJ, Yang LL. Apoptotic effects of γ-mangostin from the fruit hull of Garcinia mangostana on human malignant glioma cells. Molecules. 2010;15:8953–8966. doi: 10.3390/molecules15128953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung SH, Shen KH, Wu CH, Liu CL, et al. α-Mangostin suppresses PC-3 human prostate carcinoma cell metastasis by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-2/9 and urokinase- plasminogen expression through the JNK signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:1291–1298. doi: 10.1021/jf8032683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi YW, Chien ST, Chen PS, Lee JH, et al. α-Mangostin suppresses phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced MMP-2/MMP-9 expression via α v β-integrin/FAK/ERK and NFκB signaling pathway in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2010;58:31–44. doi: 10.1007/s12013-010-9091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krajarng A, Nakamura Y, Suksumrarn S, Watanapokasin R. α-Mangostin induces apoptosis in human chondrosarcoma cells through down regulation of ERK/JNK and Akt signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:5746–5754. doi: 10.1021/jf200620n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo JH, Kang K, Jho EH, Chin YW, et al. α- and γ-mangostin inhibit proliferation of colon cancer cells via β-catenin gene regulation in Wnt/cGMP signaling. Food Chem. 2011;129:1550–1566. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo M, Zhang L, Ji H, Kou Y, et al. Bioavailability and antioxidant activity of a xanthone-rich mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) product in humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:8788–8792. doi: 10.1021/jf901012f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Brunner I, Han A, Hamburger M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of α-mangostin in rats after intravenous and oral application. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011;55:1–8. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kay CD, Kroon PA, Cassidy A. The bioactivity of dietary anthocyanins is likely to be mediated by their degradation products. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009;53:S92–S101. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monagas M, Urpi-Sarda M, Sanchez-Patan F, Llorach R, et al. Insights into the metabolism and microbial biotransformation of dietary flavan-3-ols and bioactivity of their metabolites. Food Funct. 2010;1:233–253. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00132e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forester SC, Waterhouse AL. Metabolites are keys to understanding health effects of wine polyphenolics. J. Nutr. 2009;139:1824S–1831S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.107664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen LG, Yang LL, Wang CC. Anti-inflammatory activity of mangostins from Garcinia mangostana. Food Chem. Toxco. 2008;46:688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakatani K, Yamakuni T, Kondo N, Arakawa T, et al. γ-Mangostin inhibits inhibitor-κB kinase activity and decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in C6 rat glioma cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:667–674. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.