Abstract

Background

Residents who live in neighborhoods that are primarily African-American, Latino, or poor are more likely to have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), less likely to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and less likely to survive. No prior studies have been conducted to understand the contributing factors that may decrease the likelihood of residents learning and performing CPR in these neighborhoods. The goal of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to learning and performing CPR in three low-income, “high-risk” predominantly African American, neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio.

Methods and Results

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approaches were used to develop and conduct six focus groups in conjunction with community partners in three target high-risk neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio in January-February 2011. Snowball and purposeful sampling, done by community liaisons, was used to recruit participants. Three reviewers analyzed the data in an iterative process to identify recurrent and unifying themes. Three major barriers to learning CPR were identified and included financial, informational, and motivational factors. Four major barriers were identified for performing CPR and included fear of legal consequences, emotional issues, knowledge, and situational concerns. Participants suggested that family/self-preservation, emotional, and economic factors may serve as potential facilitators in increasing the provision of bystander CPR.

Conclusion

The financial cost of CPR training, lack of information, and the fear of risking one's own life must be addressed when designing a community-based CPR educational program. Using data from the community can facilitate improved design and implementation of CPR programs.

Keywords: heart arrest, CPR, sudden death

Introduction

African-American and Latino adults are more likely than white adults to have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and to be found in asystole and pulseless electrical activity, both poorer prognosis rhythms when compared to ventricular fibrillation (VF)/ventricular tachycardia (VT).1-3 The neighborhood in which a person arrests may also dramatically affect his or her likelihood of receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and ultimately surviving an OHCA.4-6 Residents who live in neighborhoods that are primarily African-American, Latino, or poor are more likely to have an OHCA, less likely to receive CPR, and are less likely to survive.1, 7, 8 Therefore, such neighborhoods are important targets for public health interventions to reduce disparities in bystander CPR and OHCA survival. Previous studies, using novel spatial epidemiologic methods and public health datasets, like the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), have been conducted to identify neighborhoods as “high-risk” and potential targets for community-based interventions.4, 7, 9 Such high-risk neighborhoods are defined as having a high incidence of OHCA and low prevalence of bystander CPR when compared to their neighbors.

The HANDDS (identifying High Arrest Neighborhoods to Decrease Disparities in Survival) Program was created to understand the extent of racial/ethnic and geographic location disparities in the provision of CPR and OHCA survival and identify target areas for neighborhood-based CPR interventions (http://www.handds.org/ohca/ohca.php). In Columbus, Ohio, the first HANDDS Program site, three neighborhoods were identified as being high-risk, with the lowest prevalence of bystander CPR and highest incidence of OHCA.10 These neighborhoods were comprised of primarily African-Americans with lower socioeconomic status as compared to the rest of City of Columbus. Once these high-risk neighborhoods were identified, the next step was to understand why residents of these neighborhoods do not receive or provide CPR.

The cost of training, time required, and lack of non-English training are commonly cited reasons for why people do not learn CPR.11-18 Fear of disease transmission from mouth-to-mouth breathing, doing it incorrectly, or legal action from being unsuccessful11, 13-15, 17, 19-27 may be reasons why people do not perform CPR. However, with the introduction of “Hands Only” CPR in 2008, which requires bystanders to simply do chest compressions with no ventilations, many of these common barriers may be overcome. No previous studies have specifically targeted neighborhoods in which overall rates of learning and performing bystander are much lower than average. Accordingly, the goal of this study was to use qualitative methods, to conduct an in-depth exploration of the barriers and facilitators to learning and performing CPR in three lower income “high-risk” neighborhoods comprised of African-American residents in Columbus, Ohio.

Methods

Setting

The City of Columbus has a population of 729,369 individuals and covers approximately 212 square miles, with 65.4% of residents classified as white, 26.4% as black and 4.5% as Hispanic by the US Census Bureau.28 Approximately 95% of all medic runs within the City of Columbus are made by the single City of Columbus fire-based EMS system, which provides all advanced life support emergency medical services with at least one paramedic on each fire engine and two paramedics on all ambulances. The EMS system responds to approximately 107,000 calls annually.29

Study Design and Sample

Three spatial analytical methods were used to identify high-risk neighborhoods (defined as having a high OHCA incidence and low prevalence of bystander CPR). The analytic approach that was used to identify these census tracts is described in-depth elsewhere. 10 Briefly, data from the Columbus Fire Division cardiac arrest registry (April 2004 – September 2007) and the CARES dataset (October 2007 – April 2009), an ongoing OHCA surveillance registry that collects data from EMS systems throughout the United States, were used to identify high-risk neighborhoods (defined by census tracts) in Columbus, Ohio. Consecutive adults (≥18 years of age) who experienced OHCA of cardiac etiology and were treated by EMS were studied. Data were geocoded using ArcGIS 9.3 (Environmental Systems Research Institute [ESRI] Inc., Redlands, CA) and Geoda software (http://geodacenter.asu.edu/), and spatial analysis methods were used to identify high-risk census tracts.

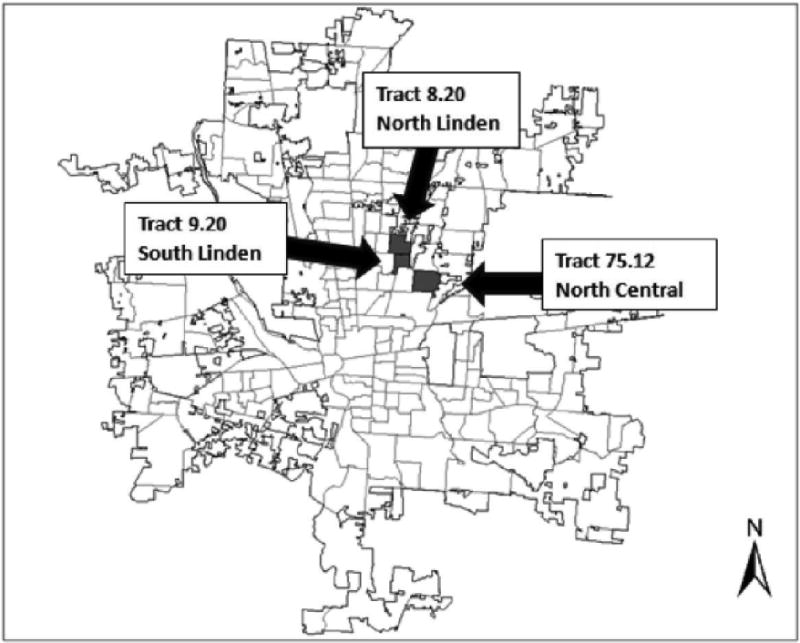

Five census tracts were identified as being high-risk. Based on existing community partnerships and consultation with community partners, three neighborhoods were identified to conduct a qualitative study to explore the barriers and facilitators to learning and providing bystander CPR (Figure 1). The North Linden, South Linden, and North Central neighborhoods had a crude annual incidence of OHCA that ranged from 0.70-1.17 per 1,000 people. During the 6-year study period, 0% of all OHCA patients received bystander CPR. These three neighborhoods were comprised of residents who were primarily African-American (range: 36.6% to 90.2%; Franklin County average: 17.9%), had a lower median household income (range: $22,333 to $33,154; Franklin County average: $42,734), and had lower high school graduation prevalence (range: 64.4%-72.0%; Franklin County average: 85.7%).

Figure 1. High-Risk Census tracts in Columbus, Ohio.

*Boundary of study area (Franklin County, Ohio). High-risk census tracts denoted with dark color.

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approaches were used to identify and partner with key community stakeholders and organizations.30 The study team included a community-based organization located within the identified high-risk neighborhoods (The Ohio State University Extension) and community liaisons who were familiar with the area and who helped identify key issues of relevance to each neighborhood and develop focus group questions. Qualitative methods were used to conduct six focus groups,31 each lasting 90-120 minutes, in January and February 2011. Prior studies have employed closed-ended surveys to measure the reasons why bystanders fail to provide CPR. Our qualitative approach with focus groups aims to provide a more in-depth understanding the phenomena of lower CPR prevalence in these target neighborhoods. Qualitative methods were oriented toward understanding rather than simply measuring phenomena. Because data collection was open-ended, research participants were free to express themselves in their own words. Through detailed, in-depth analyses of the resulting data, these methods can uncover what may drive complex decisions like choosing to learn or perform bystander CPR. As such, they are appropriate for exploring issues of disparities in bystander CPR provision in these high-risk neighborhoods.

Focus groups were conducted in lieu of one-on-one interviews, to promote interactions among focus group participants and to gain insights from the dynamics and interactions among focus group participants.31 Community liaisons recruited focus group participants using a mixture of convenience, purposeful and snowball sampling techniques. Because we were targeting a population that traditionally is difficult to reach for participation in research studies, we chose to use three common types of qualitative sampling techniques to ensure the composition of our focus groups and that the views of target neighborhood residents were well-represented. Flyers advertising the focus groups were placed in businesses (e.g., grocery stores, restaurants, public library) located in the targeted neighborhoods. Based on prior successful recruitment techniques, community liaisons conducted on-site recruitment at a local grocery store and the public library located in the target neighborhoods (convenience sample). Six radio advertisements were played during the two-month study period on a local radio station commonly listened to by residents of our three target neighborhoods. We recruited residents of the three target neighborhoods so that we could have a focus group comprised of residents from the same neighborhood (purposeful sample). Two focus groups were conducted in each of the three neighborhoods (total of 6 focus groups).32 From the respondents who agreed to attend the focus groups, we asked them to recommend others who also live in the target neighborhoods, and assist us in recruiting for future focus groups (snowball sample). Snowball sampling is a commonly used qualitative sampling technique that identifies study participants, who then recruit other potential focus group members to participate in the study. We continued to recruit participants in the focus groups until our target sample size and saturation of themes was reached.33 The coding team reached consensus that there was a saturation of themes achieved during the data analysis.32 Saturation of themes in qualitative research refers to the point in which new information is no longer being gathered from the focus groups. 34 Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for the audiotaping of the focus groups. The focus group participants were each given a ten-dollar gift card for their participation. The research protocol was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection and Processing

Six focus groups were conducted during the study period, with six to eight individuals participating in each group. To insure consistency, one investigator (CB) served as the moderator for all six focus groups, and the primary author (CS) assisted with two of the groups. The moderators used an interview guide (Appendix A), developed by the study team, to elicit comments from focus group participants related to: (1) perceived barriers to learning and performing bystander CPR; (2) familiarity with CPR; and (3) facilitators to learning and teaching CPR in high-risk neighborhoods. A video demonstrating hands-only CPR was shown to the participants. All focus groups were audiotaped. A transcription service was used to transcribe each focus group verbatim. Transcripts were stripped of personal identifiers. Participants were also asked to complete a brief survey of socio-demographic characteristics and their familiarity with CPR prior to the start of the focus group.

Data Analysis

A qualitative content analysis was used with a five stage iterative process to analyze each transcript: (1) development of a coding schedule; (2) coding of the data; (3) description of the main categories; (4) linking of categories into major themes; and (5) the development of explanations for the relations among themes.35, 36, 37 Initial or preliminary codes were created inductively from the transcripts. Three reviewers (CS, EM, and RK) read through each transcript independently and coded all transcripts line by line. The three reviewers then met to discuss the transcipts, in order to expand and refine existing categories in an iterative manner. With the full study team, the final coding structure and definitions were defined. No intercoder agreement statistics were calculated, but disagreements were resolved by consensus by the full study team. Codes were applied to the specific lines from each transcript to enable reorganization into categories (e.g., material goods), which could then be attributed to a major theme (e.g., economic incentives). The three reviewers met to question, discuss, and document interpretations and findings. Two types of audit processes were used to ensure that the content was validated. First, respondent validation was conducted: At the end of the first three focus groups, and then again at the end of the coding of the final three focus groups, the codebook was distributed to the entire research team (including the community liaisons) for input and validation. Second, multiple coders also independently coded each transcript and then met together to discuss major themes.38 Qualitative analysis software (NVivo 9.0, QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) was used to facilitate reorganization of data into codes, categories, and themes.

Results

Demographics of the focus group participants are included in Table 1. The majority of the participants were ≥30 years (82%), female (85%), and African American (83%). Approximately half of the participants were residents from the three high-risk neighborhoods (49%). Fifty-six percent of the participants had completed at least some college. Two-thirds of the participants had an annual household income of <$20,000.

Table 1. Focus Group Participant Characteristicsa.

| Number of Participants (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) (n=37) | |

| < 20 | 2 (5) |

| 20 – 29 | 1 (3) |

| 30 – 39 | 8 (22) |

| 40 – 49 | 9 (24) |

| 50 – 59 | 10 (27) |

| 60 + | 7 (19) |

| Gender (n=39) | |

| Male | 6 (15) |

| Female | 33 (85) |

| Neighborhood (n=41) | |

| North Central | 4 (7) |

| North Linden | 21 (10) |

| South Linden | 3 (32) |

| Other | 13 (51) |

| Race/Ethnicity (n=41) | |

| Black/African American | 34 (83) |

| White | 6 (15) |

| Other | 1 (2) |

| Educational Attainment (highest level) (n=41) | |

| Some High School | 7 (18) |

| Completed High School | 11 (27) |

| Some College | 11 (27) |

| Completed College | 6 (14) |

| Master's Degree | 6 (14) |

| Annual Household Income ($/yr) (n=41) | |

| < 10,000 | 22 (54) |

| 10,000 – 20,000 | 5 (12) |

| 20,000 – 30,000 | 4 (10) |

| 30,000 – 50,000 | 5 (12) |

| 50,000 – 100,0000 | 2 (5) |

| 100,000 – 200,000 | 2 (5) |

| > 200,000 | 1 (2) |

| Profession (n=31) | |

| Business/Marketing | 4 (13) |

| Housewife | 4 (13) |

| Housekeeping/Janitorial | 2 (6) |

| Nurse | 5 (16) |

| Receptionist | 3 (10) |

| Retired | 3 (10) |

| Other | 10 (32) |

Of the 42 total participants, one did not complete the pre-focus group survey. (n=41)

Table 2 illustrates the focus group participants' reported familiarity with CPR. The majority of the participants indicated that they were familiar with CPR before the focus group (88%), and more than half had taken a formal CPR course at least once in their lifetime (68%). Of those who had taken a previous CPR course, only 43% had taken the course within the previous three years.

Table 2. Familiarity of Focus Group Participants with CPRa.

| Number of Participants (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Familiar with CPR before focus group (n=41) | |

| Yes | 36 (88) |

| No | 5 (12) |

| Ever taken a formal CPR course (n=41) | |

| Yes | 28 (68) |

| No | 13 (32) |

| Time since CPR course (years) (n=28)b | |

| < 1 | 2 (7) |

| 1 – 3 | 10 (36) |

| 4 – 7 | 3 (11) |

| 8 – 14 | 4 (14) |

| 15 + | 5 (18) |

| No answer | 4 (14) |

Of the 42 total participants, one did not complete the pre-focus group survey. (n=41)

Represents the 28 individuals who responded ‘yes’ to having taken a formal CPR course.

Our analyses identified three key barriers to learning CPR (financial, lack of information, and motivation [Table 3]), four main barriers to performing CPR (consequences, emotions, knowledge, and environment [Table 4]), and three possible facilitators to learning and teaching CPR (knowledge/self-preservation, emotional factors, and economic incentives [Table 5]).

Table 3. Key Barriers to Learning CPR in High-Risk Neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio.

| Major Themes | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Financial |

|

| Informational |

|

| Motivational |

|

Table 4. Key Barriers to Performing CPR in High-Risk Neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio.

| Major Themes | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Fear of Legal Consequences |

|

| Emotional Disconnection from Community |

|

| Knowledge |

|

| Risk to Personal Health |

|

Table 5. Key Facilitators to Learning and Teaching CPR in High-Risk Neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio.

| Major Themes | Facilitators |

|---|---|

| Family / Self-Preservation |

|

| Combined CPR and First-Aid Training due to Violence in Community |

|

| Economic Incentives |

|

Barriers to learning CPR

Financial Factors

An important concern for focus group participants was the cost of taking a formal CPR course. Most participants believed the cost associated with a CPR course was the biggest barrier to learning CPR.

“Yeah, ain't that crazy? Because I want to save a life you're going to charge me. You should give us that type of knowledge for free…I mean there are certain civic responsibilities we have as citizens that should be free, and I think that this is one of them. I mean, it's not a hindrance to anybody. I don't know why all this knowledge that costs, when it's basic to help out one another.”

Participants mentioned that no CPR courses were held near where they lived. Because many residents in these neighborhoods do not own a personal vehicle, finding transportation to and from a CPR course was thought to be costly, time-consuming (sometimes requiring multiple buses), and potentially unsafe (depending on the time of day the course was held).

“For me, accessibility is always the biggest issue. There are a lot of services that are available but you really can't get to them, and you may not have the means in order to get to them.”

In addition, participants believed that paying someone to care for their children during the CPR course was an additional financial barrier, as two-thirds of the focus group participants made less than $20,000 per year.

Informational factors

There was consensus among the focus group participants that many community members did not know what a cardiac arrest was, or the importance of CPR in saving a life.

“I don't look at this community, or any community, you know, being stereotyped as okay, they're not going to do CPR; they're not going to help. Of course, I see the reality in everything that's been said, but most of the time, it's the lack of knowledge or the lack of education. The lack of education, knowing about CPR, is why you might not do it.”

Multiple participants also mentioned that they used the Internet to obtain information about CPR; however, they believed that many of their neighborhood residents did not have access to computers or other technology (e.g., Smartphones) that would allow them to obtain this information online. Participants stated that often times there was a lack of advertising about upcoming CPR trainings, most of which were not held in their community and were difficult to access. One person stated,

“Well, another thing is if, you know, there was more classes where people would be more aware of what to do, they won't be as afraid to try and save somebody.”

Finally, language was also perceived as a potential barrier, as focus group participants did not believe that there were many CPR resources available for people who did not speak English as their primary language.

Motivational factors

Focus group participants reflected that certain factors might be associated with neighborhood residents not learning CPR. Personal health issues, such as difficulty with mobility, fear of hurting oneself, or not being able to adequately provide chest compressions could be perceived as motivators for older people to not learn CPR. Respondents emphasized that programs have to explicitly find ways to motivate people to come. In addition, many CPR courses were expensive, so there may actually be a financial disincentive to learn CPR:

“What I find is a lot of times is you don't get people to show up unless there is some motivator. There's got to be an incentive or they just don't come. The interest just remains low.”

There was also the perception that in the face of multiple competing priorities, learning CPR was not a high priority when people were already struggling to make ends meet on a day-to-day basis. If CPR was not a job, educational or driver's license requirement, participants believed that people would not be motivated to learn.

Barriers to performing CPR

Fear of Legal Consequences

Focus group participants were fearful of being sued if they performed CPR, had very little knowledge of Good Samaritan laws and how those would apply in certain situations (e.g., mouth-to-mouth CPR on child). Multiple participants in each of the six focus groups were afraid of the legal consequences associated with someone doing CPR. For example, two participants in a group stated the potential consequences of not performing CPR if a person was trained,

(Participant #1) “Now, there is a reverse to that. If somebody is in trouble and you have your certification and you don't stop to help them.”

(Participant #2) “Then you can be arrested.”

(Participant #1) “You can get in some trouble. That might be a deterrent, too, why people don't take the classes and learn how to do CPR, because they don't want to be liable.”

There was also perception that doing CPR incorrectly could kill the cardiac arrest victim and that then the person doing CPR would be blamed for the death:

“Another reason a lot of people don't do CPR on somebody—because that's fear of a lawsuit. I mean, if you kill somebody, they can blame it on you for not doing it right.”

Participants were also afraid of possible consequences of hurting someone by pressing too hard and possibly puncturing a lung. This fear may be an important barrier to doing CPR.

“What kind of liability does the lay person have if they see someone collapsed and they try to do CPR on them, and say they do crack a rib and puncture a lung? Jimbo ain't going to be able to sue me, is he?”

There was also concern about the age of the victim, particularly if a child or infant sustained an arrest. Participants felt that others could perceive this situation as a person potentially trying to inappropriately touch a child.

Emotional Disconnect from Community

In general, focus group participants stated that they did not know many of their neighbors and had concerns about how well the community was connected. Participants even questioned whether a neighborhood resident would stop to assist a person in a time of need. For example one woman stated,

“You're not going to see nobody perform CPR out here. When someone witness[es] something, they'll pull out their cell phone and take pictures. They may put it on YouTube or Facebook, but they're not going to perform CPR.”

Another participant echoed these feelings, and identified a possible solution.

“This is the ‘me’ generation now, not a ‘we’ generation. If we can reverse that, if we can reverse the generation from a ‘me’ generation back to a ‘we’ generation, then more people will know CPR, more people will want to learn CPR, and more lives will be saved.”

Knowledge

Focus group participants voiced some main knowledge barriers to performing CPR. These included lack of knowledge about how and when to perform CPR, rapidly changing CPR guidelines leading to confusion and fear of doing CPR incorrectly. One participant commented on the confusion associated with rapidly changing CPR guidelines,

“And I think, with the frequent changes—I think that's the biggest thing I heard from the community, why they are always changing things, you know. Why can't they keep it the same? Because you teach them one way two years and then the next year it's changed to something different. So, the last class I taught, they were like well, why are they changing it from ABC to CBA? They've been doing ABC forever, you know. So now it's CBA so now they're confused, you know, of what to do.”

While only a minority of focus group participants had actually performed CPR, there was a consensus that people would feel panicked if they had to do CPR on a person. Even participants who had been trained in CPR voiced concerns about the ability to act in the setting of a cardiac arrest due to fears of performing CPR incorrectly.

“My grandmother collapsed in her home and my uncle works for Ohio State, and he's ACLS certified trained. But he froze because it was his mom, you know what I mean? So even if you do have the training, I pray to God I never have to use mine, and in the 13 years I've done my job, I've never had to use it. But I'm always on pins and needles, but you never know. It's scary.”

Participants believed that such uncertainties, combined with fear of legal consequences to performing CPR, could be detrimental and undermine a bystander's desire to perform CPR.

Risk to Personal Health

Focus group members described how important personal health was in their decision to not perform CPR. One of the most common barriers was the fear of breathing into a stranger's mouth:

“But it is a gross factor, you know. If you still had to do the, you know, mouth to mouth, you know, how this airborne illnesses and you know, not everybody wants to place their mouth on another person.”

There was also a potential to risk one's own personal safety to help someone else. This quote illustrates the residents' fears that stopping to help someone on the street could potentially place them in an unsafe situation (e.g. being robbed or shot). One neighborhood resident stated,

“I mean, I don't know if it's relevant in other neighborhoods, but in this one, I've walked down the street and seen people laying in the alley and I'm like, are you ours? How do I know if I need to go forward? I'd be looking around to see who might set me up.”

Incentives to learning and performing CPR

Family/Self-Preservation

The focus group participants believed residents would be more inclined to learn and perform CPR if they could see how it would be directly beneficial to their own family and friends. One woman in the group stated that this was a duty of parents and adults to protect the welfare of their children and other loved ones:

“Let's now focus on your family, your peeps, your kids, your grandkids, your mom, your dad, your grandma, your grandfather. Those are the type of people you are going to bend over backwards and going to try to save. Those are the type of people you are going to do more than call 911.”

Another mother spoke about her personal experience teaching her children to perform CPR as a as a means of self-preservation,

“Well, me being a ten-year dialysis patient, I've taught my girls to do CPR, and my oldest girl—she'll be sixteen this year, when she was about seven, she had to perform CPR on me because I was at work and I came home early, and I just got real, real dizzy and I just passed out. So by her knowing what I taught her, she saved my life.”

Combined CPR and First Aid Training due to Violence in Community

Participants stated that tying CPR training into a person's ability to save a life or being more prepared could be important reasons for a neighborhood resident to learn CPR. Combining CPR and first aid training would be very beneficial in their neighborhoods, due to the high crime rate and incidence of cardiac arrest due to violent crimes.

“Cardiac arrest doesn't just happen with heart attacks; cardiac arrest happens with people being wounded; people losing blood and that kind of thing. Because there is fairly high-level of trauma in that part of town. It [CPR training] might have a little more appeal.”

In addition, by bringing people together in a neighborhood to learn CPR, a secondary benefit could be building social capital and potentially lowering violent crime in their communities.

“Learning CPR in this community, is crucial because I'm going to give you real talk. We have a lot of homicides and taking these CPR—learning CPR, that's one way of lowering the 105 homicides that we have in this city last year.”

Economic Incentives

Focus group participants felt strongly that economic incentives, such as providing refreshments, child care, certification cards, and free CPR courses, would all facilitate high-risk neighborhood residents' desire to learn and perform CPR.

“I just know this from experience, it's hard to motivate people without incentives, so … like I said, depending on the population that you're serving, and probably the population that need it the most, there would have to be some kind of incentive, be it food, whatever, to get people to even show up. I think in some of the upper echelon communities, I don't think it would be that big of a deal to get people to show up. But then, again, [our culture] is just driven by things.”

Another participant echoed this statement,

“If we go pick up people, feed them, give them a free class, watch their kids, they might take the [CPR] class.”

In addition, obtaining personal gain through CPR training in the form of academic credit and job skills were also felt to be important facilitators to learning and teaching CPR:

“When I was in high school, no matter how well I did in health, whether it was sex education or dissecting a frog, I had to take CPR and pass in it in order to get a passing grade.”

Discussion

This is the first study to identify barriers and facilitators to learning and performing CPR in high-risk neighborhoods comprised of primarily African-American and lower median household income residents. Previous research has focused on why people do not do CPR, such as fear of doing it incorrectly,27, 39 breathing into someone's mouth,20, 40 or litigation concerns.41, 42 Our focus group participants identified barriers that are more upstream to even performing CPR, the reasons why people living in high-risk neighborhoods may not choose to even learn this life-saving procedure. The financial cost of CPR training, lack of information and the fear of risking one's own life were common barriers for learning and performing CPR and must be addressed in order to increase CPR provision in these neighborhoods.

Financial concerns were a factor in people learning CPR, as well as in motivating them to attend a CPR educational class. More than half of our participants had a self-reported household income of less than $20,000 per year. With competing demands such as housing, food, and transportation, the cost for CPR training is not feasible for many of our focus group participants. As a result, there was strong sentiment from the groups that CPR education should be made available at no cost in order to increase the numbers of people who are trained in CPR. Incentives were also perceived to be important facilitators for having people in high-risk neighborhoods learn CPR. Participants believed that free transportation to and from the training (e.g., bus tokens, etc.), childcare, food and gift cards would motivate people to attend a CPR class. In addition, combining the CPR education with educational credit, marketing it as a potential job skill, and/or combining this with driver's license requirements were all identified as possible ways to increase CPR education in these neighborhoods.

Another major theme identified by our focus group participants as a reason for low performance of CPR was the lack of information available about the signs of an OHCA, value of CPR, and fear of performing CPR incorrectly. Multiple focus group participants stated that there was a general lack of knowledge about CPR and OHCA in their neighborhoods. This is consistent with a prior study that identified important gaps in people's understanding recognizing an OHCA event.43 The American Heart Association changed its guidelines for bystander CPR to hands-only in 2008;44 however, the majority of focus group participants were unfamiliar with this change. Although the participants' stated that hands-only CPR would allay some of the common fears of breathing into one's mouth, fear of infection or being perceived as doing something inappropriate (e.g., man breathing into mouth of woman or child), there was confusion and distrust associated with rapid guideline changes. As a result, the groups stressed the importance of using local media (e.g., church-based radio stations, neighborhood-based newspapers, news broadcasts, etc.) to reach their residents and to explain the rationale behind the guideline changes. Participants indicated that having leaders from within the community advocating for and disseminating this information would increase the likelihood of actually reaching the target populations and overcome the skepticism surrounding guideline changes. Finally, tying these trainings to saving the life of one's own family and friends and making the training “personal” would be an important method for motivating people to attend a training.

Finally, there was a major theme of risking one's own life to save another's in our focus groups. Many of the participants expressed their fears of intervening or stopping to help someone due to concerns about risking their own lives. This distrust of one another and safety concerns have been seen in other areas of community-based education surrounding gang violence and crime as well.45, 46 Although many people voiced the desire to help others, there was a suspicion that the person could be “faking it” so that they could rob or even kill the person who was trying to assist. Consistent with prior literature,47 this lack of trust in one another, though understandable in high-crime neighborhoods, can further contribute to a neighborhood environment that promotes a failure to help one's own neighbors.

The underlying theme of violence will need to be explored in further detail. It may be that in high-crime areas, personal safety may be a complex topic that should be addressed with people who are learning CPR. In addition, participants indicated that many of the cardiac arrest victims they were most likely to encounter were more likely to have had a cardiac arrest due to trauma than medical issues. As a result, they recommended that more people in their neighborhoods would be motivated to attend CPR training if it were done in conjunction with basic first aid. Incorporating both types of training into a one-hour educational session would be a huge draw to the community, as violence and traumatic injuries were more applicable to the day-to-day lives of high-risk neighborhoods residents than simply just cardiac arrest of medical etiology.

A core concept we discovered through our research was a heightened awareness of the underlying pressures and concerns that high-risk neighborhood residents have when choosing to learn and/or perform bystander CPR. Beyond the financial, safety and informational concerns, there are also other barriers that must be addressed if community-based CPR trainings are going to be effective in reaching this target population. Although, we have begun to build a foundation for identifying what these factors are that drive people to acquire CPR as a skill, future research will still need to be conducted to better understand how this may be similar or different in other populations.

There are some limitations to this study. First, this was an exploratory, qualitative study to help understand barriers and facilitators to learning and performing bystander CPR in high-risk neighborhoods. There were two purposes to the study: to generate hypotheses that could be tested quantitatively in future studies, as well as building the foundation for a theoretical framework in which we begin to understand why certain target populations do not learn and/or perform CPR, with the eventual goal of creating community-based interventions that can specifically address common barriers. Given that very little prior research has been conducted in this area, we felt that qualitative methods would be an important first step in developing a better understanding of this phenomenon. In addition, future research will need to be conducted in other target populations to assess whether the hypotheses generated by this study, as well as the foundational work for the theoretical framework are applicable.

Second, we had a small number of participants. However, the individuals we interviewed were from the target areas (North Linden, South Linden and North Central), primarily African-American and the majority had household incomes below $30,000 per year. It is, of course possible that additional focus groups would elicit newer information; however, the team also felt that a saturation of themes was obtained in the process of analyzing the six focus groups. Second, 68% of the participants had participated in a formal CPR training course in the past. This may mean that our study sample is potentially more knowledgeable about CPR than the general public. Although the participants provided key insights into barriers and facilitators to learning and performing CPR, but a larger study with participants who have less experience with CPR might discover additional detail and variation. Third, there may also be some selection bias in the sample, as the focus group participants were all recruited from the area, by community liaisons who lived and worked in the neighborhoods. In addition, we chose to use three sampling techniques to ensure that our focus groups were comprised of residents from the target neighborhoods. There is a possible sampling bias, however, because we were most interested in reaching a target population living in the highest-risk neighborhoods that is traditionally difficult to reach with standard CPR training, this was actually a strength of the study. Future research will need to be conducted to examine how the barriers and facilitators to learning and performing CPR elucidated in this research may be similar or different in both non-minority populations and other groups (e.g. limited English proficiency, lower income neighborhoods in other cities). Groups were also recruited by community liaison who lived in the area as to allow participants to feel more comfortable disclosing their thoughts on why bystander CPR prevalence was low in their neighborhoods.

Research shows that a person who arrests in a primarily low-income black neighborhood is two times less likely to receive bystander CPR. This is the first systematic study to generate hypotheses as to why residents living in the highest-risk neighborhoods are both less likely to learn and perform CPR. Qualitative methods, using focus groups, done in partnership with local community-based organizations, were used in order to understand the underlying causes for this disparity. Future research will need to be conducted to evaluate implementation of community-based CPR trainings designed to overcome these important barriers, in conjunction with residents from the highest-risk neighborhoods. These findings will have major policy implications as we move beyond the description of health disparities to finding solutions that will help us design effective programs to decrease health disparities in the provision of bystander CPR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was funded by the University of Michigan Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program. Dr. Sasson is supported, in part, by awards from the Emergency Medicine Foundation and American Heart Association. Dr. Haukoos is supported, in part, by an Independent Scientist Award (K02 HS017526) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and an Investigator-Initiated Grant (R01 AI106057) from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Heisler is supported in part by the Veterans' Administration DM-QUERI grant, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (P30DK092926).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Comilla Sasson, American Heart Association. Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado; Aurora, CO.

Jason S. Haukoos, Department of Emergency Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Department of Epidemiology, Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, CO.

Cindy Bond, ABD Ohio State University Extension. Columbus, OH.

Marilyn Rabe, Ohio State University Extension. Columbus, OH.

Susan H. Colbert, Ohio State University Extension. Columbus, OH.

Renee King, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado; Aurora, CO.

Michael Sayre, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Michele Heisler, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

References

- 1.Galea S, Blaney S, Nandi A, Silverman R, Vlahov D, Foltin G, Kusick M, Tunik M, Richmond N. Explaining racial disparities in incidence of and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:534–543. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirbaugh PE, Pepe PE, Shook JE, Kimball KT, Goldman MJ, Ward MA, Mann DM. A prospective, population-based study of the demographics, epidemiology, management, and outcome of out-of-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:174–184. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vadeboncoeur TF, Richman PB, Darkoh M, Chikani V, Clark L, Bobrow BJ. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the Hispanic vs the non-Hispanic populations. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA, Becker LB. Neighborhoods matter: a population-based study of provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)80047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasson C, Keirns CC, Smith D, Sayre M, Macy M, Meurer W, McNally BF, Kellermann AL, Iwashyna TJ. Small area variations in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: does the neighborhood matter? Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:19–22. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaillancourt C, Lui A, De Maio VJ, Wells GA, Stiell IG. Socioeconomic status influences bystander CPR and survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims. Resuscitation. 2008;79:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasson C, Magid DJ, Chan P, Root ED, McNally BF, Kellermann AL, Haukoos JS. Association of neighborhood characteristics with bystander-initiated CPR. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1607–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerner EB, Fairbanks RJ, Shah MN. Identification of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest clusters using a geographic information system. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:81–84. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasson C, Cudnik MT, Nassel A, Semple H, Magid DJ, Sayre M, Keseg D, Haukoos JS, Warden CR. Identifying high-risk geographic areas for cardiac arrest using three methods for cluster analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu KH, May CR, Clark MJ, Breeze KM. CPR training in households of patients with chest pain. Resuscitation. 2003;57:257–268. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flabouris A. Ethnicity and proficiency in English as factors affecting community cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) class attendance. Resuscitation. 1996;32:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(96)00942-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanstad BK, Nilsen SA, Fredriksen K. CPR knowledge and attitude to performing bystander CPR among secondary school students in Norway. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Clark AP. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for family members. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009;28:156–163. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181a473ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locke CJ, Berg RA, Sanders AB, Davis MF, Milander MM, Kern KB, Ewy GA. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Concerns about mouth-to-mouth contact. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:938–943. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.9.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meischke H, Taylor V, Calhoun R, Liu Q, Sos C, Tu SP, Yip MP, Eisenberg D. Preparedness for cardiac emergencies among Cambodians with limited English proficiency. J Community Health. 2012;37:176–180. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9433-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platz E, Scheatzle MD, Pepe PE, Dearwater SR. Attitudes towards CPR training and performance in family members of patients with heart disease. Resuscitation. 2000;47:273–280. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reder S, Quan L. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in Washington state public high schools. Resuscitation. 2003;56:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Eigel B, Hickey RW, Longstreth WT, Jr, Nadkarni V, Nichol G, Sayre MR, Sommargren CE, Hazinski MF. Reducing barriers for implementation of bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association for healthcare providers, policymakers, and community leaders regarding the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2008;117:704–709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley SM, Rea TD. Improving bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:219–224. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834697d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coons SJ, Guy MC. Performing bystander CPR for sudden cardiac arrest: behavioral intentions among the general adult population in Arizona. Resuscitation. 2009;80:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwyer T. Psychological factors inhibit family members' confidence to initiate CPR. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:157–161. doi: 10.1080/10903120801907216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston TC, Clark MJ, Dingle GA, FitzGerald G. Factors influencing Queenslanders' willingness to perform bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;56:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormack AP, Damon SK, Eisenberg MS. Disagreeable physical characteristics affecting bystander CPR. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:283–285. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolan RP, Wilson E, Shuster M, Rowe BH, Stewart D, Zambon S. Readiness to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an emerging strategy against sudden cardiac death. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:546–551. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith KL, Cameron PA, Meyer AD, McNeil JJ. Is the public equipped to act in out of hospital cardiac emergencies? Emerg Med J. 2003;20:85–87. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swor R, Khan I, Domeier R, Honeycutt L, Chu K, Compton S. CPR training and CPR performance: do CPR-trained bystanders perform CPR? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:596–601. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. [Accessed May 20, 2013]; Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/39/3918000.html.

- 29.Keseg DP. Personal Communication. Sep 17, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, Lopez J, Butz A, Mosley A, Coates L, Lambert G, Potito PA, Brenner B, Rivera M, Romero H, Thompson B, Coronado G, Halstead S. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbour RS. Making sense of focus groups. Med Educ. 2005;39:742–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaskell G. A Practical Handbook. London: SAGE Publications; 2000. Individual and Group Interviewing., Qualitative Researching With Text, Image and Sound. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS. 2005:S67–72. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000172879.20628.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Given LM. Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Publications, Incorporated; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayring P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2000;2 Art. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbour R. Checklist for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001;322:1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaillancourt C, Stiell IG, Wells GA. Understanding and improving low bystander CPR rates: a systematic review of the literature. CJEM. 2008;10:51–65. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500010010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taniguchi T, Sato K, Fujita T, Okajima M, Takamura M. Attitudes to bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan in 2010. Circ J. 2012;76:1130–1135. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho GC, Sohn YD, Kang KH, Lee WW, Lim KS, Kim W, Oh BJ, Choi DH, Yeom SR, Lim H. The effect of basic life support education on laypersons,Äô willingness in performing bystander hands only cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81:691–694. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischer P, Krueger J, Greitemeyer T, Vogrincic C, Kastenmuller A, Frey D, Heene M, Wicher M, Kainbacher M. The bystander-effect: a meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:517–537. doi: 10.1037/a0023304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradley SM, Fahrenbruch CE, Meischke H, Allen J, Bloomingdale M, Rea TD. Bystander CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: The role of limited English proficiency. Resuscitation. 2011;82:680–684. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sayre MR, Berg RA, Cave DM, Page RL, Potts J, White RD. Hands-only (compression-only) cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a call to action for bystander response to adults who experience out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest: a science advisory for the public from the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee. Circulation. 2008;117:2162–2167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.189380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Wilkinson RG. Crime: social disorganization and relative deprivation. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:719–731. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ. 1997;314:1037–1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King RA, Moreno E, Sayre M, Colbert S, Bond-Zielinski C, Sasson C. How to Design a Targeted, Community-Based Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Intervention for High-Risk Neighborhood Residents. Annals of emergency medicine. 2011;58:S281. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.