Abstract

The fetal development of the anterior subventricular zone (SVZ) involves the transformation of radial glia into neural stem cells, in addition to the migration of neuroblasts from the SVZ towards different regions in the brain. In adult rodents this migration from the anterior SVZ is restricted to the olfactory bulb following a rostral migratory stream (RMS) formed by chains of migratory neuroblasts. Similar to rodents, an RMS has been suggested in the adult human brain, where the SVZ remains as an active proliferative region. Nevertheless, a human fetal RMS has not been described and the presence of migratory neuroblasts in the adult remains controversial. Here we describe the cytoarchitecture of the human SVZ at the lateral ganglionic eminence late in the second trimester of development (23–24 weeks postconception). Cell organization in this region is heterogeneous along the ventricular wall, with GFAP-positive cells aligned to the ventricle. These cells coexpress markers for radial glia like GFAPδ, nestin, and vimentin. We also show the presence of abundant migratory neuroblasts in the anterior horn SVZ forming structures here denominated cell throngs. Interestingly, a ventral extension of the lateral ventricle suggests the presence of a putative RMS. Nevertheless, in the olfactory bulb neuroblast throngs or chain-like structures were not observed. The lack of these structures closer to the olfactory bulb could indicate a destination for the migratory neuroblasts outside the olfactory bulb in the human brain.

Keywords: subventricular zone, rostral migratory stream, neuroblast migration, olfactory bulb

During early brain development, after the closing of the neural tube, proliferative cells from the neural plate form the ventricular zone (VZ) in the mammalian brain (Bystron et al., 2008). After symmetrical divisions, nuclei of VZ cells become distributed through interkinetic nuclear movements and form a pseudostratified epithelium, which create the ependyma later during development (Boulder Committee, 1970; Bystron et al., 2008). Postmitotic neuroblasts emerge from the VZ and migrate to the neocortex using processes from the radial glia cells (RG) as guides (Rakic, 1971; Kriegstein and Noctor, 2004). While these events occur, a second group of dividing cells appears behind the VZ forming the region known as the subventricular zone (SVZ) (Boulder Committee, 1970; Bystron et al., 2008). In a phenomenon only described in humans, RG migrate out of the VZ into the parenchyma, maintaining a basal process contacting the ventricular surface. Once in the parenchyma, these RG undergo cell division and migrate back to the VZ before differentiating (Hansen et al., 2010). By midgestation most RG cells start transforming into GFAP+ astrocytes (de Azevedo et al., 2003), with some of them retaining neurogenic potential (Mo et al., 2007). By gestational weeks 25–27 in humans, the VZ is reduced to a single cell epithelium and virtually stops its mitotic activity while the SVZ keeps proliferating (Zecevic et al., 2005).

In adult rodents, cell proliferation in the SVZ continues, making it the most active neurogenic region in the adult brain (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2008). SVZ type B1 astrocytes have been identified as bona fide neural stem cells; they divide asymmetrically to give rise to the transient amplifying type C cells, which then become type A cells (Doetsch et al., 1999). Type A cells, surrounded by type B2 cells, form migratory chains in the SVZ and move towards the olfactory bulb (OB) through the rostral migratory stream (RMS) (Lois et al., 1996). Once in the OB, neuroblasts differentiate into olfactory interneurons (Doetsch et al., 1999; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2008).

In the adult human brain, neural stem cells can also be isolated from the SVZ (Sanai et al., 2004); however, the SVZ cytoarchitecture is significantly different from the one in rodents. Astrocytes are not found adjacent to the ependyma; instead, cell bodies of human SVZ astrocytes accumulate in a ribbon-like structure, separated from the ependymal layer by a gap that is largely devoid of cells, with some astrocytes extending a long process that crosses this gap and touches the ventricular surface (Sanai et al., 2004; Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006). Further, there has been no description of type C cells or chains of migratory neuroblasts and the existence of an RMS in the human adult brain has been a subject of debate (Bedard and Parent, 2004; Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006; Curtis et al., 2007; Sanai et al., 2004, 2007; Kam et al., 2009; van den Berge et al., 2010).

Four divisions in the SVZ are found in the forebrain during human fetal development: three ganglionic eminences (medial, lateral, and caudal) and the fetal neocortical SVZ (Brazel et al., 2003). The lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE) gives rise to the adult anterior SVZ and the majority of interneurons in the olfactory glomerulus (Young et al., 2007). The human ganglionic eminences (GE) have been studied as a source for basal ganglia and cortical neurons, and have been the focus of extensive review articles (Ulfig, 2002; Brazel et al., 2003). Nevertheless, little is known about the cellular organization of neural stem cells and progenitor-related markers in the human LGE and the anterior extension of the lateral ventricles connecting to the olfactory tract and bulb.

With the use of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, we describe the cytoarchitecture of the anterior human LGE and the rostral extension of the lateral ventricles during the second trimester of prenatal development. Deciphering the organization of the fetal human LGE and its rostral extension will help in understanding the normal development of the adult SVZ. This is of paramount importance since increased cell proliferation, altered rates of cell death, and migration in the human LGE-SVZ have been implicated in childhood and adult brain tumors as well as neurodegenerative diseases (Lewis, 1968; Zecevic et al., 2005; Lim et al., 2007; Chaichana et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection and processing

We collected seven complete human fetal brains ranging from 23–24 gestation weeks (g.w.) within 4 hours postelective abortion. All procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the UCSF Committee on Human Research (CHR no. H11170-19113). Specimens had no clinical or postmortem evidence of brain pathology. Five complete brains were processed for light microscopy and two for electron microscopy (EM).

For light microscopy, cerebral hemispheres were fixed by bilateral internal carotid artery perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4. Fixed hemispheres were cut coronally into 1.5–2.0 cm sections, postfixed by immersion in 4% PFA for 2 weeks, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for 2 weeks. For EM, brains were immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde + 2% PFA for 24 hours and subsequently rinsed with 0.1 M PB. Fetal brain tissue was cut along the rostrocaudal axis of the lateral ventricle and the sections were divided into three regions as previously reported in the adult human brain: anterior horn, body of the ventricle, and atrium/occipital horn (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006).

The LGE was identified according to previous descriptions of human brain development (Brazel et al., 2003; Bayer and Altman, 2007), as the most dorsal elevation in the lateral wall of the lateral ventricles (Fig. 1A–C); limited laterally by the caudate nucleus and the internal capsule, ventrally by the MGE, and dorsally by the corpus callosum. The wall of the ventricles in each of these regions was studied in two zones according to the recommendations of the Boulder Committee (1970): the VZ, a pseudostratified epithelial monolayer that surrounds the wall of ventricles; and the SVZ, a region generated by the accumulation of basal progenitors (Fig. 1D–F) (Bystron et al., 2008).

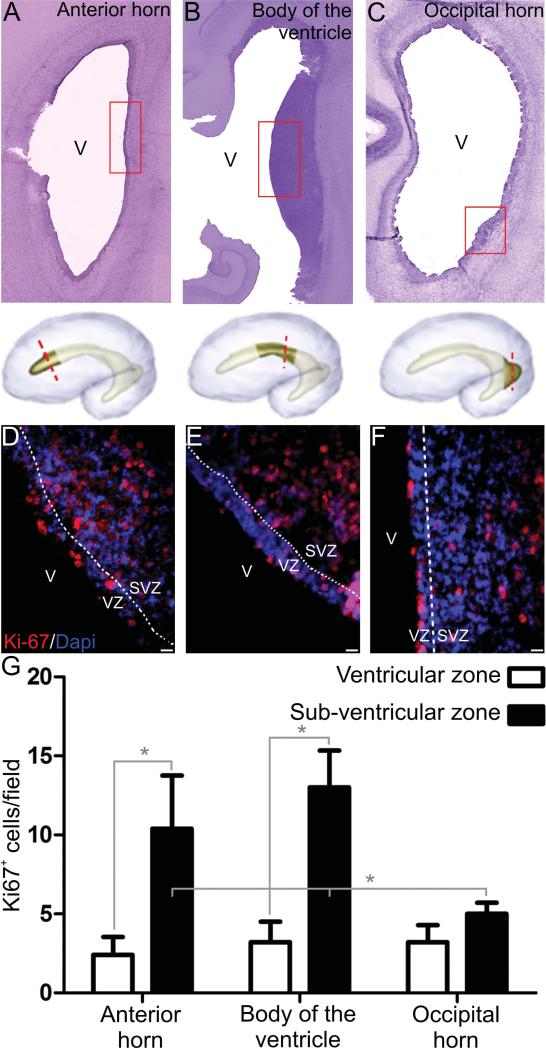

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation in the ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE) and caudal ganglionic eminence. Representative images of coronal sections from the human fetal anterior horn (A), body of the ventricle (B), and occipital horn (C), stained with cresyl violet. Red rectangles show the areas where Ki67 expression was quantified. D–F: Representative images of Ki67 immunostains at different regions. G: Ki67+ cell quantification shows a higher proliferation rate in the SVZ when compared to the VZ. Higher proliferation is more evident in the anterior horn and the body of the ventricle when compared to the occipital horn *P < 0.05. V, Ventricle; VZ, ventricular zone; SVZ, subventricular zone. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Cryostat sectioning and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

PFA fixed specimens were frozen in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA) and sectioned on a cryostat (10-μm sections). For an initial morphological overview of the human SVZ under the light microscope, serial 30–50-μm sections were cut on a cryostat and stained with cresyl violet. In order to evaluate the rostral extension of the lateral ventricles, semisagittal sections were obtained at a 30° angle in relation to the lateral ventricle, intersecting the anterior horn and the olfactory tract. Cryostat-obtained sections were thoroughly rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in blocking solution consisting of 10% normal goat serum (NGS), diluted in PBS with 0.1% Triton. Sections were then incubated for 24 hours at 4° C in primary antibody diluted in 2% NGS blocking solution (Table 1). Following primary antibody incubation, sections were rinsed in PBS and then incubated in the appropriate fluorescent secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) at a dilution of 1:500 for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (40 ng/mL) for 5 minutes at room temperature and mounted in Aqua Polymount (Polysciences, Warrington, PA).

TABLE 1.

List of Antibodies

| Antibody | Source/Cat. | Immunogen | Host | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doublecortin | Millipore/AB 5910 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 350-365 of mouse and human Doublecortin (DCX) protein ( LYLPLSLDSDSLGDSM) | Guinea pig | 1:1000 |

| GFAP | Millipore/ MAB 3402 | Purified GFAP from porcine spinal cord | Mouse | 1:500 |

| GFAP | Dako/ Z 0334 | GFAP isolated from cow spinal cord | Rabbit | 1:500 |

| GFAPδ | Abcam/ab28926 | Synthetic peptide (QAHQIVNGTPPARG) corresponding to C terminal amino acids 418-431 of Human GFAP delta | Rabbit | 1:500 |

| Ki-67 | Novocastra/NCL-Ki-67p | Bacterially expressed residues 1159 to 1522 of human Ki67 | Rabbit | 1:1,000 |

| Nestin | Millipore/MAB5326 | Fragment derived from cloned nestin cDNA of human fetal brain cells coupled to glutathione S-transferase (PWDDSLRGAVAGAPKTALETESQDSAEPSGSEEESDPVSLEREDKVPGPLEIPSGMEDAGPGADIIGVNGQGPNLEGKSQHVNGGVMNGLEQSEEVGQGMPLVSEGDRGSPFQEEEGSALKTSWAGAPVHLGQGQFLKFTQREGDRESWS) | Mouse | 1:200 |

| Pax-6 | Covance/prb-278P | Fragment of C-terminus of the mouse Pax-6 protein (QVPGSEPDMSQYWPRLQ) | Rabbit | 1:300 |

| Sox-2 | Santa Cruz/sc-17320 | Synthetic peptide corresponding to aa 277-293 of the human SOX2 (YLPGAEVPEPAAPSRLH) | Goat | 1:500 |

| Vimentin | Sigma Aldrich/V6630 | Purified protein from pig eye lens | Mouse | 1:200 |

Antibody characterization and image acquisition

Antibody information is summarized in Table 1. Double-cortin (DCx) is a microtubule associated protein expressed by migratory neuroblasts (Doetsch et al., 1997; Eriksson et al., 1998; Mizuguchi et al., 1999; Ligon et al., 2004). This polyclonal antibody detects a single band of 40 kDa in immunoblots of rat developing retina (Lee et al., 2003). The antibody has been used to label mouse brain migrating neurons in previous reports, showing the same staining pattern as in our results (Tran et al., 2007).

GFAP is an intermediate filament protein expressed by astrocytes (Mizuguchi et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2004). We used two antibodies to identify GFAP-positive cells in our study: 1) a rabbit polyclonal antibody which recognizes the native protein (48 kDa) and a proteolytic GFAP fragment (40–47 kDa) in mouse brain protein extracts via western blot (Gerdes et al., 1991; Key et al., 1993; Bedard and Parent, 2004). The staining pattern observed in this study is similar to the one reported in human SVZ (Rodda et al., 2005); 2) a mouse monoclonal GFAP antibody (Millipore, Bedford, MA; Cat. No. MAB 3402) which identifies a single 51-kDa band on western blots of porcine brain lysates (manufacturer's information). The expression pattern observed in this study is similar to that reported previously in adult human SVZ (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006).

The GFAPδ isoform is specifically present in the population of astrocytes that are neural stem cells in the adult human brain (Roelofs et al., 2005). The anti-GFAPδ antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; Cat. No. ab28926) detects a single band of ≈60 kDa on immunoblots of whole-cell lysates of human astrocytoma-derived cell lines U373 and U343 (Perng et al., 2008). The staining pattern found in our study is similar to previous observations on fetal and adult human brain (Roelofs et al., 2005).

Ki-67 is a large nuclear protein of about 360 kDa used as a marker of proliferating cells (Gerdes et al., 1983). The rabbit polyclonal antibody (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; Cat. No. NCL-Ki-67p) specifically recognizes human, mouse, and rat Ki67 nuclear antigen on all proliferating cells during late G1, S, M, and G2 phases (Gerdes et al., 1984).

Nestin is a high-molecular-weight (MW 240,000), class VI intermediate filament protein transiently expressed during mammalian development (Hockfield and McKay, 1985) and in proliferating central nervous system (CNS) progenitor cells (Lendahl et al., 1990). This antibody (Millipore, MAB5326) detects a double band of 220–240 kDa on whole-cell lysates from U373 and U251 human glioma cell lines and the immortalized human neuroglial cell line SVG (Messam et al., 2000). Cultured fetal human neural progenitors are labeled with this antibody (Messam et al., 2000). The staining pattern observed in this work is similar to the one observed in adult human brain (Leonard et al., 2009).

Pax-6 is a homeobox domain protein expressed in the developing nervous system (Walther and Gruss, 1991; Davis and Reed, 1996). The Pax6 antibody (Covance, Richmond, CA; prb-278P) detects two bands of ≈50 kDa by immunoblot of tissue from the adult brain, eye, and OB (Walther and Gruss, 1991; Davis and Reed, 1996). The expression pattern found in this study is similar to the one observed previously in adult human brain (Curtis et al., 2007).

The transcription factor Sox-2 is implicated in the process of cell fate decision during development (Miyagi et al., 2004). The Sox-2 antibody used here (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-17320) detects a band of 34 kDa in western blots of human and mouse embryonic stem cells (manufacturer's information). The staining pattern found in this study is similar to previous reports on rodents tissue (Navarro-Quiroga et al., 2006), and adult human SVZ (Baer et al., 2007).

Vimentin is an intermediate filament protein frequently found as a marker immature neuroepithelial cells (Dahl et al., 1981). The antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; V6630) detects a 58-kDa band on western blots of human fibroblast extracts (manufacturer's information) and U343 human astrocytoma cell extracts (Langlois et al., 2002). The staining pattern observed in this study is similar to the one reported on rat (Berglof et al., 2007) and adult human SVZ (Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006).

Brightfield images were taken with a digital camera (SPOT camera, Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) connected to a light microscope (Olympus, Lake Success; NYAX70). Fluorescence images were taken with an ORCA II camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) connected to an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope. Image brightness and contrast were adjusted using Slidebook software (Olympus).

Electron microscopy

Brain sections fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde + 2% PFA and cut on a vibratome in transverse or sagittal 200-μm sections. Sections were postfixed in 2% osmium for 2 hours, rinsed, dehydrated, and embedded in Durcupan resin (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). Serial 1-μm semithin sections were stained with 1% Toluidine blue and examined with a light microscope to study the overall organization of the SVZ. Ultrathin (0.07 μm) sections were cut with a diamond knife, stained with lead citrate, and examined under an FEI Tecnai Spirit G2 electron microscope using a digital camera (Morada, Soft Imaging System, Olympus) to identify individual cell types.

Cell count and statistical analysis

To quantify the number of proliferating cells in the VZ and SVZ of the anterior horn, body of the ventricle, and occipital horn, we performed IHC against Ki-67 as described above. Ki-67-positive cells from five high-powered fields (40×) per slide per region were counted by three blinded observers in two brains. Proliferation values were compared among regions and evaluated using a two-way analysis of variance, followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. Statistical significance was established if P < 0.05 was achieved.

RESULTS

Cell proliferation in the VZ and SVZ

To determine cell proliferation, Ki-67-positive cells were quantified in the LGE of the anterior horn, the body of the ventricle, and the caudal GE of the occipital horn (Fig. 1A–C). We found a more robust presence of Ki-67-positive cells in the SVZ (10.4 ± 3.36 cells/field) when compared to the epithelial cells of the VZ (2.4 ± 1.14 cells/field) in the anterior horn (t:6.68 (2,24), P < 0.05). Similar observations were made in the body of the ventricle (SVZ: 13 ± 2.34, VZ: 3.2 ± 1.304 cells/field. t:8.19 (2,24), P < 0.05). No significant differences were found in the occipital horn. Comparing these three areas, cell proliferation in the SVZ was significantly higher in the body of the ventricle (q:7.449) and anterior horn (q:5.028), as compared to the occipital horn (F(2,12) = 14.44, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1G). These data suggest that by 23 weeks of gestation cells in the VZ have decreased their proliferation rate and a more active SVZ emerges as the main site of cell division, especially at the more anterior regions.

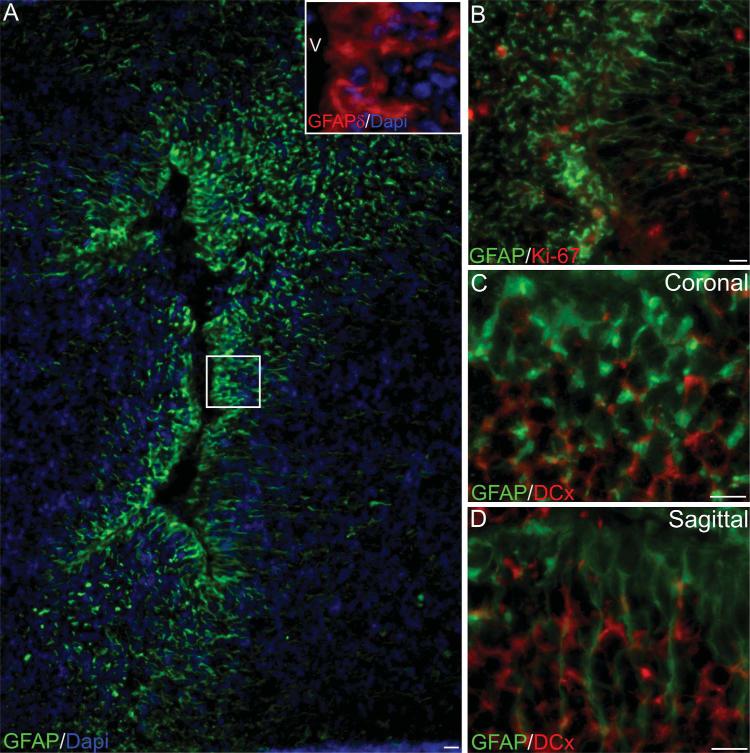

Expression of GFAP, vimentin, nestin, pax-6, and sox-2 in the human anterior horn

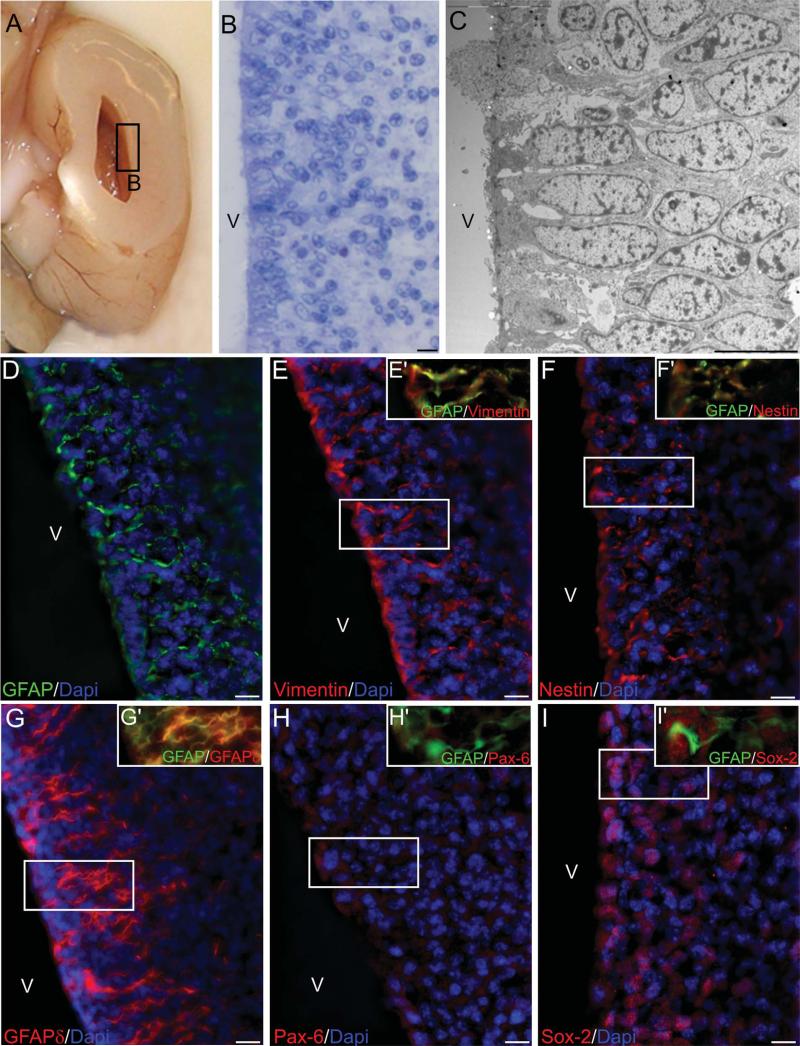

The VZ of this region showed cells arranged as a one-cell thick pseudostratified epithelium (Fig. 2B,C). Most cells in the VZ expressed markers of radial glia such as GFAP, vimentin, and nestin (Fig. 2D–F). We also evaluated the expression of the delta isoform of GFAP (GFAPδ), as well as the transcription factors Sox-2 and Pax-6 in coronal sections of the anterior horn. In the VZ and the SVZ, while GFAP-positive cells were found to coexpress GFAPδ and Sox-2 (Fig. 2E′–I′), Pax-6 was not found in this region (Fig. 2H). GFAPδ is a splice variant of GFAP that appears to be specifically expressed by multipotent neural stem cells in the human adult and fetal SVZ (Roelofs et al., 2005; Middeldorp et al., 2010; van den Berge et al., 2010). Here we show a restricted expression of GFAPδ to cells in the VZ and SVZ area that have short processes extending into the brain parenchyma.

Figure 2.

Cell organization of the anterior horn (AH) LGE. A: Coronal section of a human fetal brain anterior horn. B: Cresyl violet-stained section showing a pseudostratified epithelium. C: EM image showing cells touching the ventricular wall, with cell nuclei arranged at different levels forming the pseudostratified appearance. D: Ventricular epithelial cells express GFAP filaments and arrange their process in a radial manner, these cell elongations coexpress vimentin (E), nestin (F), and GFAPδ (G). No specific expression of Pax-6 was observed in this region (H) while Sox-2 was abundant in both the VZ and the SVZ (I). Insets (E′–I′) show coexpression of the different proteins with GFAP. V, ventricle. Scale bars = 10 μm.

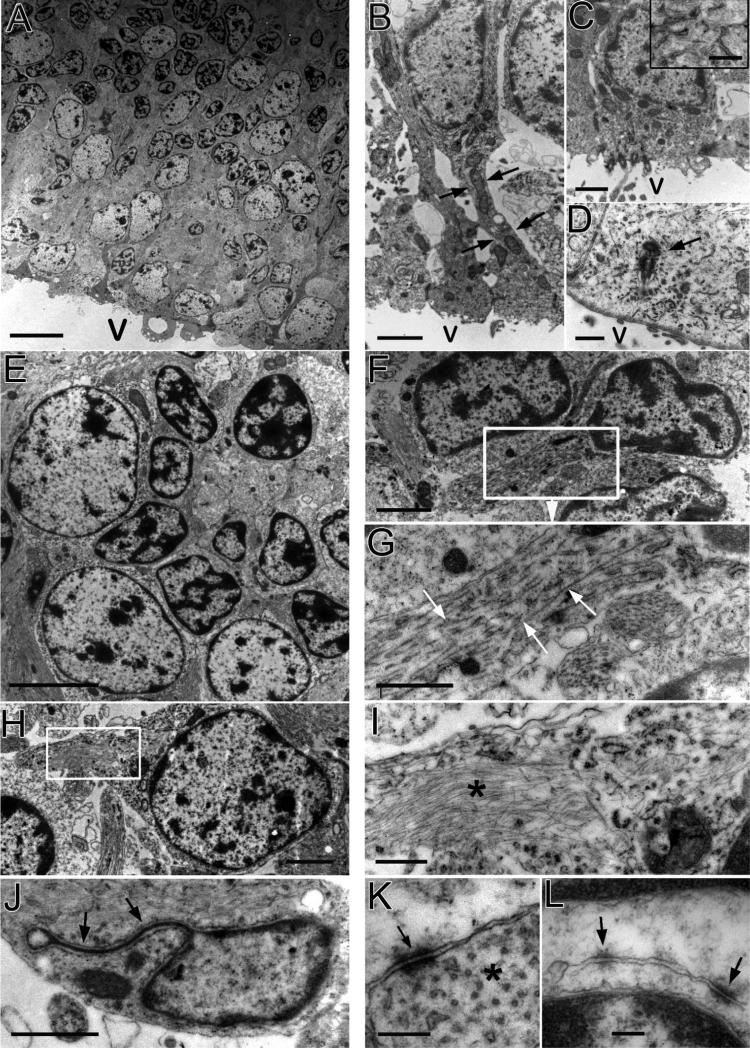

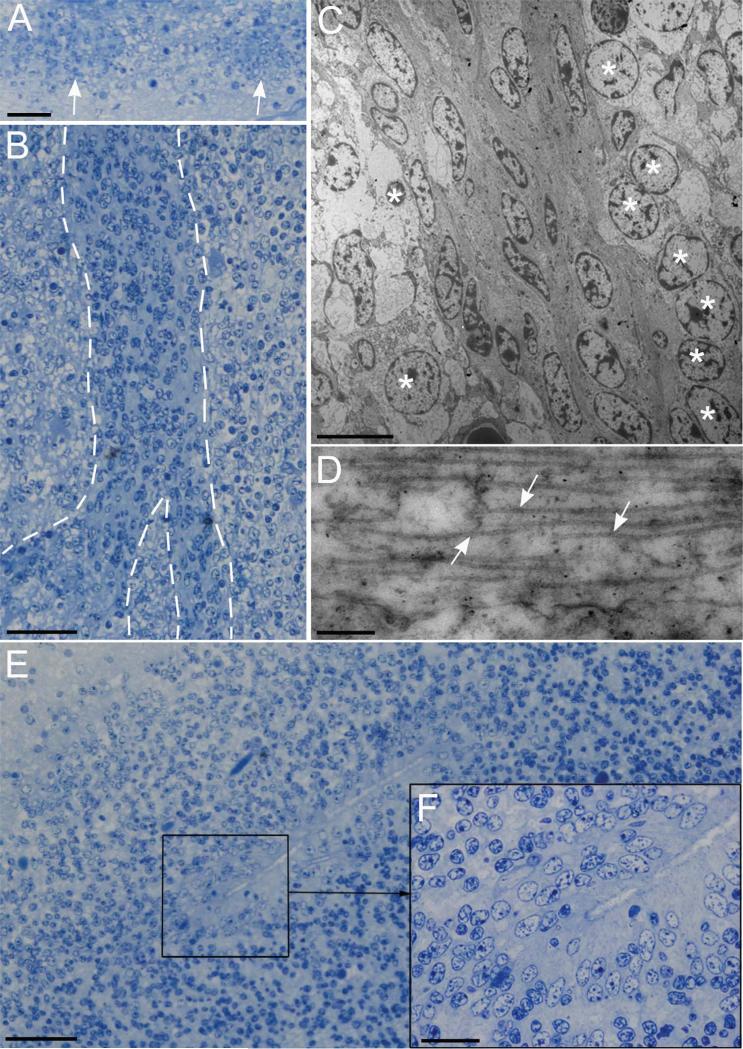

To further investigate the cytoarchitecture of the human anterior horn LGE, EM analysis was performed. In this region the VZ and the SVZ are clearly distinguishable through EM (Fig. 3A). The VZ is formed by a pseudostratified epithelium of cells rich in intermediate filaments, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum cisternae. Cell nuclei are distributed adjacent to the ventricular surface or up to 35 μm away from it, in cells extending long processes that touch the ventricular surface thereby forming the pseudostratified structure (Fig. 3B). Two types of cells are observed in the VZ: multiciliated (Fig. 3C) and uniciliated (Fig. 3D) cells, with the latter being more abundant in this region. Both types of cells present union complexes, interdigitations, and microvillus in their apical portion and abundant intermediate filaments basally. Multiciliated cells also present multiple basal bodies associated with mitochondria while uniciliated cells present a perpendicular centriole and fewer mitochondria. The SVZ presents a group of cells with no particular organization and greater density of cytoplasmic extensions running in every direction, while cells from the VZ are mostly organized in a radial fashion. Two cell types can be identified in this layer: one with large and clear cytoplasm (large-clear cells) and with noncondensed chromatin in the nucleus; one with small and dark cytoplasm (small-dark cells) and condensed chromatin (Fig. 3E). Small-dark cells present abundant microtubules, a ribosome-rich cytoplasm, small endoplasmic reticulum cisternae, and little dictyosomes (Fig. 3F–G). Large-clear cells are characterized by spherical nuclei with areas of nuclear membrane fusion (Fig. 3J) and abundant intermediate filaments, with extensions that do not display a defined direction in the neuropil (Fig. 3H,I). They also have abundant organelles and few ribosomes and endoplasmic reticulum cisternae. Other characteristic observed in this region is the presence of intercellular adherent junctions, which are observed between the same cell types (i.e., two clear cells) and between two different cells (Fig. 3K,L). The finding of two clearly distinct cell populations in this region indicates a high degree of specialization during the late second trimester of gestation.

Figure 3.

EM analysis of the AH LGE. A: Two cell types (large-clear and amall-dark) are observed in this region. B: A pseudostratified epithelium is formed by cell nuclei distributed adjacent to the ventricular wall or several microns away. B: Some cells extend long apical processes to contact the ventricular wall (arrows). C,D: Multiciliated and uniciliated cells (respectively) are observed in this region, arrow shows the basal corpuscle and centriole of a uniciliated cell. E: Two types of SVZ cells are observed, one with large and clear cytoplasm and nucleus, with noncondensed chromatin, and one with small and dark cytoplasm and nucleus with more condensed chromatin. F: A group of small cells with dark nuclei and small ribosome-rich cytoplasm, small endoplasmic reticulum cisternae and little dictyosomes. These cells present abundant microtubuli as shown in G (arrows). H: Cells with clear nuclei are characterized by the presence of abundant intermediate filaments, organelles, and few ribosomes and endoplasmic reticulum cisternae. I: Detail showing the intermediate filaments (asterisk). J: Clear nucleus cell with areas of nuclear fusion (arrows), tight junctions (arrows) can be observed between clear and dark nucleus cells (K); and between two clear cells (L). Asterisk in K shows transversal sections of intermediate filaments found in a dark nucleus cell. Scale bars = 10 μm in A; 2 μm in B,C,F,H (inset in C: 0.5 μm); 1 μm in D,G,I; E: 5 μm; 0.5 μm in J; 200 nm in K,L.

Rostral extension of the anterior horn

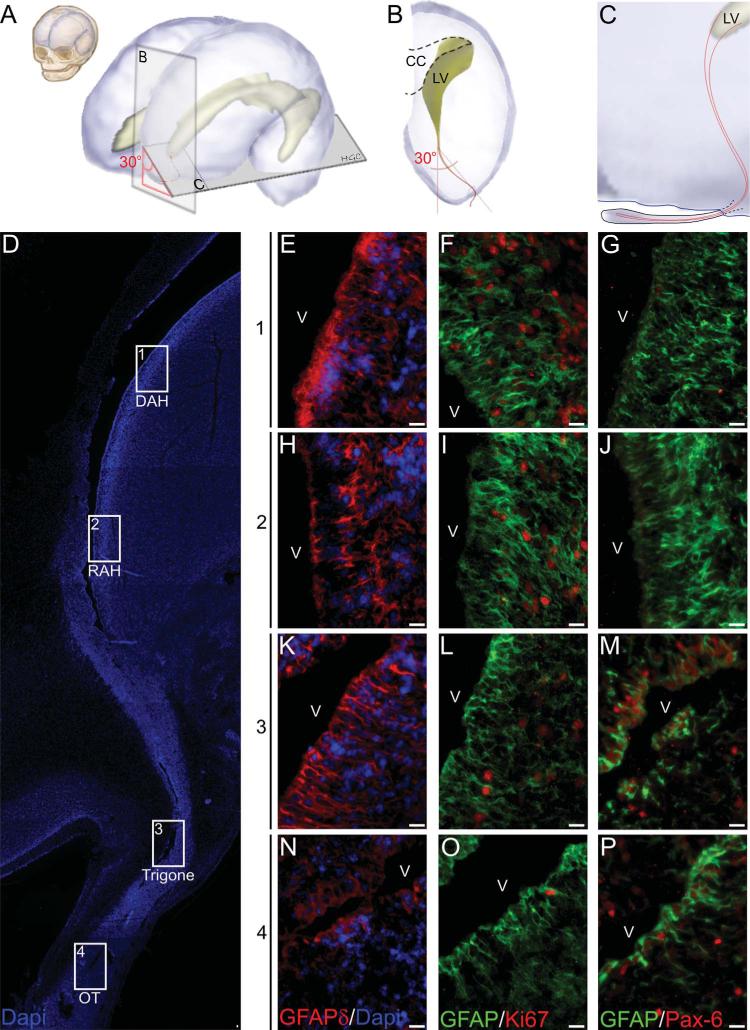

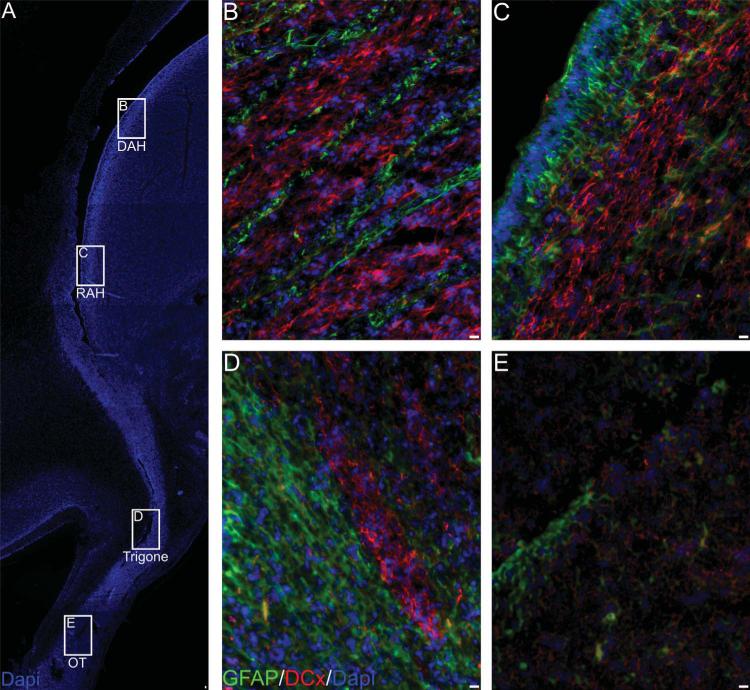

To analyze a possible connection between the anterior horn of the lateral ventricles and the olfactory tract, we obtained semisagittal sections angled at 30° in relation to a lateral sagittal plane (Fig. 4A–C), thereby intersecting both areas. These sections allowed us to visualize the anterior horn, the olfactory tract, and the olfactory bulb in the same section. Interestingly, we observed a rostral extension of the lateral ventricle with cells aligned along the ventricular path from the anterior horn to the olfactory bulb (Fig. 4D). We evaluated this connection at four different levels: a dorsal portion of the anterior horn (DAH) (Fig. 4E–G), a rostral portion of the anterior horn (RAH) (Fig. 4H–J), the olfactory trigone (trigone) (Fig. 4K–M), and the olfactory tract (OT) (Fig. 4N–P). In all of these regions we found GFAPδ-positive cells aligned with the ventricular surface (Fig. 4E,H,K,N). Ki-67 expression was found to be abundant in the DAH and less frequent in the OT (Fig. 4F,I,L,O), the same distribution was observed when immunostained for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (data not shown). Staining for Pax-6 cells found positive nuclei that were abundant in the trigone and the OT, while almost no positive cells were found at the DAH or the RAH (Fig. 4G,J,M,P). These observations suggest the presence of proliferating undifferentiated cells surrounding a rostral extension of the ventricular wall, which connects the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle and the OT.

Figure 4.

Rostral extension of the lateral ventricle in the human fetal brain. A: Diagram representing the human fetal brain at 20 weeks of gestation. B,C: The lateral ventricle anterior horn extends into the olfactory bulb at a lateral inclination of 30° from the ventricle. D: Semi-sagittal section, stained with the nuclear dye DAPI. The ventricular opening extends from the lateral ventricle to the olfactory bulb. Cells from the ventricular wall are positive for GFAPδ in all the regions studied (E,H,K,N). Ki-67-positive cells are more abundant in the DAH (F), RAH (I), and trigone (L) when compared to the OT (O). Pax-6-positive cells are absent in the DAH (G) and RAH (J) and present in the more rostral regions of the trigone (M) and the OT (P). CC, corpus callosum; LV lateral ventricle; V, ventricle; DAH, Dorsal anterior horn; RAH, Rostral anterior horn; OT, olfactory tract. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Migratory neuroblasts in the human fetal SVZ and the rostral extension of the lateral ventricle

To evaluate the presence of migratory neuroblasts, we determined the presence of DCx-positive cells in the SVZ and the lateral ventricle rostral extension into the olfactory bulb (Fig. 5A). At the level of the lateral ventricle, we observed abundant groups of DCx-positive cells, denominated hereafter as cell throngs, with elongated morphology mixed with GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 5B,C). As we approached the olfactory trigone, cell throngs become thinner and the structures formed by DCx-positive cells resemble the migratory chains observed in rodents RMS (Fig. 5D). We found that DCx-positive cells in the SVZ and the olfactory trigone are associated with GFAP-positive cells running parallel to them (Fig. 5B–D). This characteristic is absent in the OT areas, where DCx-positive cells were not associated with GFAP-positive cells and displayed a nonelongated morphology (Fig. 5E). Nevertheless, under the electron microscope it was possible to observe small-dark cells forming chain-like structures surrounded by large-clear cells (Fig. 6A–C). Small-dark cells in this area were also characterized by abundant microtubules similar to the ones observed in SVZ dark cells (Fig. 6D). Small-dark cells in the olfactory tract form chain-like structures that bifurcate forming thinner structures, as shown in Figure 6B. These ultrastructural features corroborate the resemblance with the migratory chains observed in rodents RMS

Figure 5.

Doublecortin (DCx)-positive structures in the anterior SVZ. A: Reconstruction of the entire connection between the anterior horn and the olfactory tract. DCx+ cells were found at every region with different organization. At the DAH (B), RAH (C), and olfactory trigone (D) DCx+ cells were found aligned to GFAP-positive cells. At the OT, no GFAP+ cells were observed in alignment with the less abundant DCx+ cells. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Figure 6.

A: Transversal section of the olfactory trigone where a large group of dark nucleus cells (arrows) is surrounded by clear nucleus cells. B: Longitudinal section of the olfactory tract showing a bifurcating chain of dark nucleus cells surrounded by clear nucleus cells. C: EM image of a chain of dark nucleus cells showing an elongated morphology. These cells are surrounded by groups of clear cells with round nuclei (*). D: High-magnification image showing microtubules in a dark nucleus cell. E,F: Semithin section of the olfactory bulb showing a ventricular lumen delimited by a pseudostratified epithelium. Scale bars = 50 μm in A,B,E; 8 μm in C; 250 nm in D; 20 μm in F.

Cytoarchitecture of the human fetal olfactory ventricle

The cytoarchitecture of the olfactory bulb at the ventricular opening showed an organization similar to the one observed in the SVZ. Two distinct cell types were observed (i.e., small and dark, and large and clear) (Fig. 6E,F). Coronal and sagittal sections of the human fetal olfactory bulb were performed and immunostained for GFAP, GFAPδ, Ki-67, and DCx. GFAP-positive cells, coexpressing GFAPδ were found aligned to the ventricular surface as observed in the previously studied regions (Fig. 7A). Abundant Ki-67-positive cells were observed, with no restriction to the areas surrounding the ventricle (Fig. 7B). To evaluate the presence of migratory neuroblasts we evaluated the immunoreactivity to DCx. As observed in the olfactory tract, DCx-positive cells in the olfactory bulb present a rounded morphology that was observed in both coronal (Fig. 7C) and sagittal sections (Fig. 7D). The nature of these DCx-positive cells remains to be studied.

Figure 7.

Cytoarchitecture of the human fetal olfactory ventricle. A: GFAP-positive cells align to the olfactory bulb ventricle similarly to the anterior horn. These GFAP-positive cells also coexpress the GFAPδ isoform (inset). B: Ki67-positive cells are observed in the OB parenchyma but none were found in the ventricular wall. DCx-positive fibers are observed in this region but no clear alignment was observed either on coronal (C) or sagittal (D) sections. V, ventricle. Scale bars = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Despite the SVZ being the most active germinal region of the adult mammalian brain, it remains relatively poorly understood in humans. The principal aim of the present study was to provide a basic description of the architecture and ultrastructure of the VZ and the SVZ at the LGE of the human fetal lateral ventricle and the ventricular connection to the olfactory bulb. The ganglionic eminences (medial, lateral, and caudal) are involved in the development of the striatum, putamen, and other cortical and subcortical structures (Wichterle et al., 2001; Marshall and Goldman, 2002; Brazel et al., 2003; Young et al., 2007). The LGE in particular is responsible for the development of the adult anterior SVZ (Marshall and Goldman, 2002; Young et al., 2007).

Our findings indicate that at this age: 1) Two clearly distinct layers are observed in the LGE, a VZ formed by a monolayer of cells and a SVZ formed by dark-small and clear-large cells. 2) Cell proliferation is more abundant in the SVZ when compared to the VZ. 3) Human fetal LGE presents a heterogeneous cytoarchitecture which includes GFAP-positive cells coexpressing neurogenesis-related markers, such as GFAPδ, Vimentin, Nestin, and Sox-2. 4) A rostral extension of the lateral ventricle, comprised of throngs of DCx-positive cells with a migratory morphology, extends into the olfactory bulb.

Organization of the human fetal lateral ganglionic eminence

During brain development in rodents, cell proliferation in the VZ decreases during the last part of gestation, while SVZ increases its proliferative capacity, reaching a proliferation peak in the postnatal period (Takahashi et al., 1995; Tramontin et al., 2003). Here we show that by the second trimester of fetal development in humans cell proliferation is already more prominent in the SVZ than in the VZ, especially in its more anterior regions, as reported in rodents (Doetsch et al., 2002).

In the analysis of late second trimester fetal brain we observed a heterogeneous cell organization in the fetal SVZ with two distinct cell types. Contrary to what occurs in the adult SVZ in rodents (Garcia-Verdugo et al., 1998), these cells do not exhibit a particular organizational pattern. Instead, GFAP-positive cells, coexpressing Nestin, Vimentin, and GFAPδ, are arranged next to the ventricular surface and are also found deeper into the SVZ extending short processes into the brain parenchyma. In a recent report by Hansen et al. (2010), a group of cells morphologically and phenotypically similar to radial glia were found in the human fetal outer SVZ. The origin of these cells is postulated to be in the VZ (Hansen et al., 2010). The use of live cell imaging in human fetal organotypic cultures could help to determine if the GFAPδ/vimentin-positive cells found in the present work are able to migrate into the brain parenchyma and give rise to outer SVZ radial glial cells.

Migratory neuroblasts in the human fetal SVZ

We observed a large number of DCx-positive cells that throng parallel to the ventricular surface. DCx is a microtubule protein expressed by migratory neuroblasts (Brown et al., 2003). In the rodent brain a widespread network of pathways for chain migration extends throughout most of the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle (Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996). Many of these chains join the RMS leading to the olfactory bulb (Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996; Alonso et al., 1999). Similar chains have also been described in primates (Kornack and Rakic, 2001; Pencea et al., 2001; Gil-Perotin et al., 2009). Chains of migrating cells in the adult rodent and monkey brain can also be visualized with PSA-NCAM antibodies (Rousselot et al., 1995; Bonfanti et al., 1997; Kornack and Rakic, 2001). A previous study reports clusters of PSA-NCAM+ cells in the human SVZ of children less than 1 year old (Weickert et al., 2000). Similarly, the expression of DCx by cells in the VZ and SVZ of human fetal brain has been previously observed (Meyer et al., 2002). Here we describe a large amount of DCx-positive cells found in the SVZ of the anterior horn. However, these cells do not present an organized orientation pattern. Under EM in rodents, migratory neuroblasts are observed as small dark cells (Doetsch et al., 1997); here we describe similar small-dark cells in the human fetal SVZ, suggesting that migratory neuroblasts are present in the human fetal SVZ. Although we observe small-dark cells adjacent to astrocyte-like large-clear cells, no gliotubes were observed. We also found some cells that have both microtubules and intermediate filaments, which may indicate that some of these cells are more likely transforming from a radial glia state to a young precursor migratory state, as described previously (Li et al., 2002).

One of the most intriguing and interesting aspects of the adult human SVZ is that it differs significantly from other mammals previously studied. In the SVZ of mice (Doetsch et al., 1997), dogs (Blakemore and Jolly, 1972), and primates (Kornack and Rakic, 2001; Pencea et al., 2001), astrocytes lie directly next to the ependymal layer. In contrast, human adult SVZ astrocytes are separated from the ependyma by a region largely devoid of cell bodies and very rich in processes from astrocytes and ependymal cells (layer II) (Sanai et al., 2004; Quinones-Hinojosa et al., 2006). The present data in SVZ of the human fetal brain indicate that there is no hypocellular gap present throughout the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle. This region is instead occupied by numerous migratory neuroblasts. We postulate that layer II of the adult human SVZ may represent an embryonic remnant of the migratory pathway that fetal neuroblasts leave behind during brain development.

Rostral extension of the lateral ventricle anterior horn

In rodents, neuroblasts born in the adult SVZ migrate through an extensive network of interconnected pathways to reach the RMS (Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996). The RMS ends in the olfactory bulb, where young neurons differentiate into local interneurons in the olfactory granule layer. This process has been demonstrated in the brain of adult rodents (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994) and primates (Kornack and Rakic, 2001; Pencea et al., 2001), and has been suggested in adult humans (Curtis et al., 2007; van den Berge et al., 2010). Here we show that during the second trimester of human fetal brain development a ventricular surface can be observed from the anterior horn of the lateral ventricles towards the olfactory bulb., Nestin, vimentin, and GFAPδ-positive cells are found throughout these regions aligned to the ventricular surface. Nevertheless, contrary to the findings by Curtis et al. (2007) in the adult human brain, we did not observe evidence of strong proliferative activity in the olfactory tract or the olfactory bulb, as evidenced by Ki-67 immunostaining. The greater importance of olfaction in the adult life could explain a more intense cellular proliferation in these regions in the adult brain. In opposition to Ki-67 expression, Pax-6 expression is virtually absent in the anterior horn SVZ and increases in the trigone and the OT. This finding is in accordance with previous reports in mice (Hack et al., 2005) and adult humans (Curtis et al., 2007), showing Pax-6 absent in the SVZ and expressed in the RMS as progenitor cells differentiate into a more neuronal lineage (Hack et al., 2005). The expression pattern of Pax-6 has a very dynamic distribution during human fetal brain development (Mo and Zecevic, 2008; Larsen et al., 2010). At the GE, high levels of Pax-6 expression precede periods of prominent cell proliferation (Larsen et al., 2010), a phenomenon also observed in rodents (Osumi et al., 2008). Prenatal cell fate in the VZ and SVZ is determined by a complex interaction of transcription factors like Pax6, Sonic Hedgehog, Nkx2.2, and Gsh2, among others (Yun et al., 2001; Kallur et al., 2008; Genethliou et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010). Pax-6 expression is closely related to a neuronal fate in the human fetal SVZ at the LGE, where a robust expression of Pax-6 is present at 15 g.w. (Mo and Zecevic, 2008). In the work by Mo and Zecevic the expression of Pax-6 in the LGE was not reported by immunohistochemistry after 15 g.w. Nevertheless, in culture, some cells derived from 20 g.w. human fetal SVZ coexpress Pax-6 and Olig-2 (Mo and Zecevic, 2008). The presence of Pax-6-negative cells found in our study could indicate a decrease in cell proliferation and a possible commitment to a glial cell lineage. Nevertheless, given the narrow period of development studied, the cell fate of these Pax-6-negative cells remains to be determined at later time-points in human fetal brain development using other methodological approaches.

Our findings indicate the presence of a ventral extension of the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle with DCx-positive cells going through the olfactory tract and reaching the olfactory bulb. In the DAH and RAH SVZ DCx-positive cells form thick structures here denominated cell throngs that are separated by GFAP-positive cells. Under EM analysis we observe groups of small dark cells that resemble the chains of migratory neuroblasts described in rodents. The presence of a connection between the anterior horn and the olfactory bulb suggests a migratory stream of neuroblasts in the fetal brain. However, we cannot establish whether this phenomenon persists in the adult brain or if the structures observed by other groups are only remnants of the fetal ventricular surface, left behind after the closing of the ventricular extension during development (Humphrey, 1940) and not an active migratory pathway.

In summary, here we provide a description of the SVZ in the human fetal LGE during the late second trimester. The cell organization and cytoarchitecture of this fetal region is heterogeneous along the ventricle, with GFAPδ-positive cells aligned to the ventricular surface. Interestingly, a ventral extension of the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle appears to generate a putative rostral migratory stream of neuroblasts that reach the olfactory bulb. The presence of throngs of DCx-positive cells in this region indicates similarities in neuroblasts migratory mechanisms between rodents and humans. Nevertheless, the characteristics of these structures change as they approach the olfactory bulb where no chain-like structures are observed and cell proliferation is minimal. Thus, the final destination of human fetal SVZ neuroblasts remains to be determined. The use of live cell imaging in preserved viable tissue will help elucidate the fate of SVZ neuroblasts as well as the molecular mechanisms regulating their migration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Liron Noiman, BA, for important feedback on the article and Sofie Christensen, BA, Ashwini Niranjan, BS, and Claudia Ruiz, BS, for their help on this work.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: K08NS055851 (to A.Q.H., G.Z.); Grant sponsor: Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (to H.G.C.); from the Grant sponsor: Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain TERCEL; Grant number: (SAF 2008-01274 (to J.M.G.V., M.S.); Grant sponsor: CONACyT; Grant number: CB-2008-101476 (to O.G.P.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Alonso G, Prieto M, Chauvet N. Tangential migration of young neurons arising from the subventricular zone of adult rats is impaired by surgical lesions passing through their natural migratory pathway. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:508–528. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990322)405:4<508::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Kohwi M, Nguyen TM, Merkle FT. The heterogeneity of adult neural stem cells and the emerging complexity of their niche. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:357–365. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Eriksson PS, Faull RL, Rees MI, Curtis MA. Sox-2 is expressed by glial and progenitor cells and Pax-6 is expressed by neuroblasts in the human subventricular zone. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:828–831. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA, Altman J. Atlas of human central nervous system development. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard A, Parent A. Evidence of newly generated neurons in the human olfactory bulb. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;151:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglof E, Af Bjerken S, Stromberg I. Glial influence on nerve fiber formation from rat ventral mesencephalic organotypic tissue cultures. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:431–442. doi: 10.1002/cne.21251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore WF, Jolly RD. The subependymal plate and associated ependyma in the dog. An ultrastructural study. J Neurocytol. 1972;1:69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01098647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L, Peretto P, Merighi A, Fasolo A. Newly-generated cells from the rostral migratory stream in the accessory olfactory bulb of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1997;81:489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulder Committee Embryonic vertebrate central nervous system: revised terminology. Anat Rec. 1970;166:257–261. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091660214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazel CY, Romanko MJ, Rothstein RP, Levison SW. Roles of the mammalian subventricular zone in brain development. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:49–69. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JP, Couillard-Despres S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG. Transient expression of double-cortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.10874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystron I, Blakemore C, Rakic P. Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:110–122. doi: 10.1038/nrn2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaichana KL, McGirt MJ, Frazier J, Attenello F, Guerrero-Cazares H, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to the lateral ventricles predicts survival following tumor resection. J Neurooncol. 2008;89:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, Holtas S, van Roon-Mom WM, Bjork-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, Frisen J, Dragunow M, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science. 2007;315:1243–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1136281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl D, Rueger DC, Bignami A, Weber K, Osborn M. Vimentin, the 57 000 molecular weight protein of fibro-blast filaments, is the major cytoskeletal component in immature glia. Eur J Cell Biol. 1981;24:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JA, Reed RR. Role of Olf-1 and Pax-6 transcription factors in neurodevelopment. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5082–5094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05082.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo LC, Fallet C, Moura-Neto V, Daumas-Duport C, Hedin-Pereira C, Lent R. Cortical radial glial cells in human fetuses: depth-correlated transformation into astrocytes. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:288–298. doi: 10.1002/neu.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Alvarez-Buylla A. Network of tangential pathways for neuronal migration in adult mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14895–14900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5046–5061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nord-borg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F, Wichterle H, Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Architecture and cell types of the adult subventricular zone: in search of the stem cells. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:234–248. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199808)36:2<234::aid-neu10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J, Schwab U, Lemke H, Stein H. Production of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with a human nuclear antigen associated with cell proliferation. Int J Cancer. 1983;31:13–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker HH, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984;133:1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J, Li L, Schlueter C, Duchrow M, Wohlenberg C, Gerlach C, Stahmer I, Kloth S, Brandt E, Flad HD. Immunobiochemical and molecular biologic characterization of the cell proliferation-associated nuclear antigen that is defined by monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:867–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Perotin S, Duran-Moreno M, Belzunegui S, Luquin MR, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Ultrastructure of the subventricular zone in Macaca fascicularis and evidence of a mouse-like migratory stream. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514:533–554. doi: 10.1002/cne.22026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack MA, Saghatelyan A, de Chevigny A, Pfeifer A, Ashery-Padan R, Lledo PM, Gotz M. Neuronal fate determinants of adult olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:865–872. doi: 10.1038/nn1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Lui JH, Parker PR, Kriegstein AR. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature. 2010;464:554–561. doi: 10.1038/nature08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockfield S, McKay RD. Identification of major cell classes in the developing mammalian nervous system. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3310–3328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03310.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T. The development of the olfactory and the accessory olfactory formations in human embryos and fetuses. J Comp Neurol. 1940;73:431–468. [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO, Xie L, Cottrell BA, Henshall DC, Greenberg DA. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:343–347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam M, Curtis MA, McGlashan SR, Connor B, Nannmark U, Faull RL. The cellular composition and morphological organization of the rostral migratory stream in the adult human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;37:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key G, Becker MH, Baron B, Duchrow M, Schluter C, Flad HD, Gerdes J. New Ki-67-equivalent murine monoclonal antibodies (MIB 1–3) generated against bacterially expressed parts of the Ki-67 cDNA containing three 62 base pair repetitive elements encoding for the Ki-67 epitope. Lab Invest. 1993;68:629–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. The generation, migration, and differentiation of olfactory neurons in the adult primate brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein AR, Noctor SC. Patterns of neuronal migration in the embryonic cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois A, Lee S, Kim DS, Dirks PB, Rutka JT. p16(ink4a) and retinoic acid modulate rhoA and GFAP expression during induction of a stellate phenotype in U343 MG-A astrocytoma cells. Glia. 2002;40:85–94. doi: 10.1002/glia.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KB, Lutterodt MC, Laursen H, Graem N, Pakkenberg B, Mollgard K, Moller M. Spatiotemporal distribution of PAX6 and MEIS2 expression and total cell numbers in the ganglionic eminence in the early developing human fore-brain. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:149–162. doi: 10.1159/000297602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Kim IB, Lee E, Kwon SO, Oh SJ, Chun MH. Differential expression and cellular localization of doublecortin in the developing rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1542–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BW, Mastroeni D, Grover A, Liu Q, Yang K, Gao M, Wu J, Pootrakul D, van den Berge SA, Hol EM, Rogers J. Subventricular zone neural progenitors from rapid brain autopsies of elderly subjects with and without neuro-degenerative disease. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:269–294. doi: 10.1002/cne.22040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PD. Mitotic activity in the primate subependymal layer and the genesis of gliomas. Nature. 1968;217:974–975. doi: 10.1038/217974a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu F, Salmonsen RA, Turner TK, Litofsky NS, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Jones SN, Recht LD, Ross AH. PTEN in neural precursor cells: regulation of migration, apoptosis, and proliferation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:21–29. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon KL, Alberta JA, Kho AT, Weiss J, Kwaan MR, Nutt CL, Louis DN, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. The oligodendroglial lineage marker OLIG2 is universally expressed in diffuse gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:499–509. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DA, Cha S, Mayo MC, Chen MH, Keles E, VandenBerg S, Berger MS. Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to neural stem cell regions predicts invasive and multifocal tumor phenotype. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:424–429. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chain migration of neuronal precursors. Science. 1996;271:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CA, Goldman JE. Subpallial dlx2-expressing cells give rise to astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the cerebral cortex and white matter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9821–9830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messam CA, Hou J, Major EO. Coexpression of nestin in neural and glial cells in the developing human CNS defined by a human-specific anti-nestin antibody. Exp Neurol. 2000;161:585–596. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Perez-Garcia CG, Gleeson JG. Selective expression of doublecortin and LIS1 in developing human cortex suggests unique modes of neuronal movement. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1225–1236. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp J, Boer K, Sluijs JA, De Filippis L, Encha-Razavi F, Vescovi AL, Swaab DF, Aronica E, Hol EM. GFAP-delta in radial glia and subventricular zone progenitors in the developing human cortex. Development. 2010;137:313–321. doi: 10.1242/dev.041632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi S, Saito T, Mizutani K, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y, Iwama A, Nakauchi H, Masui S, Niwa H, Nishimoto M, Muramatsu M, Okuda A. The Sox-2 regulatory regions display their activities in two distinct types of multipotent stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4207–4220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4207-4220.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi M, Qin J, Yamada M, Ikeda K, Takashima S. High expression of doublecortin and KIAA0369 protein in fetal brain suggests their specific role in neuronal migration. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1713–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65486-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z, Zecevic N. Is Pax6 critical for neurogenesis in the human fetal brain? Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1455–1465. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z, Moore AR, Filipovic R, Ogawa Y, Kazuhiro I, Antic SD, Zecevic N. Human cortical neurons originate from radial glia and neuron-restricted progenitors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4132–4145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0111-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Quiroga I, Hernandez-Valdes M, Lin SL, Naegele JR. Postnatal cellular contributions of the hippocampus subventricular zone to the dentate gyrus, corpus callosum, fimbria, and cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:833–845. doi: 10.1002/cne.21037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi N, Shinohara H, Numayama-Tsuruta K, Maekawa M. Concise review: Pax6 transcription factor contributes to both embryonic and adult neurogenesis as a multi-functional regulator. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1663–1672. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencea V, Bingaman KD, Freedman LJ, Luskin MB. Neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and rostral migratory stream of the neonatal and adult primate forebrain. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:1–16. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng MD, Wen SF, Gibbon T, Middeldorp J, Sluijs J, Hol EM, Quinlan RA. Glial fibrillary acidic protein filaments can tolerate the incorporation of assembly-compromised GFAP-delta, but with consequences for filament organization and alphaB-crystallin association. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4521–4533. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Hinojosa A, Sanai N, Soriano-Navarro M, Gonzalez-Perez O, Mirzadeh Z, Gil-Perotin S, Romero-Rodriguez R, Berger MS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cellular composition and cytoarchitecture of the adult human subventricular zone: a niche of neural stem cells. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:415–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Guidance of neurons migrating to the fetal monkey neocortex. Brain Res. 1971;33:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda DJ, Chew JL, Lim LH, Loh YH, Wang B, Ng HH, Robson P. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24731–24737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs RF, Fischer DF, Houtman SH, Sluijs JA, Van Haren W, Van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM. Adult human subventricular, subgranular, and subpial zones contain astrocytes with a specialized intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Glia. 2005;52:289–300. doi: 10.1002/glia.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselot P, Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Embryonic (PSA) N-CAM reveals chains of migrating neuroblasts between the lateral ventricle and the olfactory bulb of adult mice. J Comp Neurol. 1995;351:51–61. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, Lawton MT, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Manuel-Garcia Verdugo J, Berger MS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Berger MS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Comment on “Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension.”. Science. 2007;318:393. doi: 10.1126/science.318.5849.393a. author reply 393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS., Jr Early ontogeny of the secondary proliferative population of the embryonic murine cerebral wall. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6058–6068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06058.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramontin AD, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Postnatal development of radial glia and the ventricular zone (VZ): a continuum of the neural stem cell compartment. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:580–587. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Banisadr G, Ren D, Chenn A, Miller RJ. Chemokine receptor expression by neural progenitor cells in neurogenic regions of mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:1007–1033. doi: 10.1002/cne.21229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulfig N. Ganglionic eminence of the human fetal brain—new vistas. Anat Rec. 2002;267:191–195. doi: 10.1002/ar.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berge SA, Middeldorp J, Zhang CE, Curtis MA, Leonard BW, Mastroeni D, Voorn P, van de Berg WD, Huitinga I, Hol EM. Longterm quiescent cells in the aged human subventricular neurogenic system specifically express GFAP-delta. Aging Cell. 2010;9:313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther C, Gruss P. Pax-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS. Development. 1991;113:1435–1449. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Webster MJ, Colvin SM, Herman MM, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Localization of epidermal growth factor receptors and putative neuroblasts in human subependymal zone. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:359–372. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000731)423:3<359::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Turnbull DH, Nery S, Fishell G, Alvarez-Buylla A. In utero fate mapping reveals distinct migratory pathways and fates of neurons born in the mammalian basal forebrain. Development. 2001;128:3759–3771. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KM, Fogarty M, Kessaris N, Richardson WD. Subventricular zone stem cells are heterogeneous with respect to their embryonic origins and neurogenic fates in the adult olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8286–8296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0476-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic N, Chen Y, Filipovic R. Contributions of cortical subventricular zone to the development of the human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:109–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.20714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]