Abstract

Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) antagonists rapidly reduce testosterone and are preferred to LHRH agonists in situations when early response is important. The lack of flare reaction, as compared to LHRH agonists, is particularly desirable as it would not aggravate the problem. A 78-year-old man presented with symptoms of urinary tract obstruction. He had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) of 91.3 ug/L and serum creatinine 146 umol/L. He had a large pelvic mass due to histologically confirmed prostate cancer, resulting in moderate left hydronephrosis and deteriorating renal function (serum creatinine of 163 umol/L). He was started on combined degarelix and bicalutamide on the day of consultation (day 0). The hydronephrosis resolved on the repeat computerized tomography scan performed on day 10. Serum creatinine normalized to under 130 umol/L on day 18. The PSA fell to 11 ug/L on day 18, 2.8 ug/L on day 28, and 0.5 ug/L on day 53. Therefore, LHRH antagonists are particularly useful in urgent situations. It is the preferred choice in these circumstances.

Introduction

Patients with advanced prostate cancers are treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with or without radiotherapy. For many years, orchiectomy or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists have been used. LHRH antagonists, such as degarelix, have been developed as they rapidly reduce testosterone and are preferred to LHRH agonists in situations when early response is important. The lack of flare reaction, as compared to LHRH agonists, is particularly desirable as it would not aggravate the problem (e.g., spinal cord compression, bone pain or urinary obstruction). With our patient, we decided to treat his prostate cancer with degarelix to improve his deteriorating renal function due to urinary tract obstruction.

Case report

A 78-year-old male presented with stage IV carcinoma of the prostate, T4N0M0. He had stomach discomfort for 1.5 months and lower urinary tract obstructive symptoms for 2 months. The family doctor did some blood tests and found that the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was 91.3 ug/L. A prostate biopsy showed an adenocarcinoma of Gleason score 9 (5+4). Transrectal ultrasound showed a large mass above the base of the prostate.

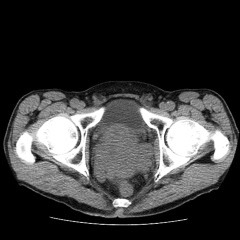

Due to an elevated serum creatinine of 146 umol/L 3 weeks before, an urgent renal function and non-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis were performed on the day of consultation. Serum creatinine came back to be 163 umol/L. His CT scan showed a large lobulated pelvic mass which indented the bladder base and the anterior wall of the rectum (Fig. 1). It extended to the left pelvic sidewall in contact with the obturator internus muscle. The seminal vesicles could not be discerned. The mass measured 8.3 × 8.1 cm. No enlarged nodes were present more superiorly in the pelvis and there was no retroperitoneal nodal enlargement. There was moderate left hydronephrosis and hydroureter which could be traced to the level of the large prostatic pelvic mass (Fig. 2). There was no right hydronephrosis.

Fig. 1.

Computerized tomography scan at the level of prostate on day 0.

Fig. 2.

Computerized tomography scan at the level of kidneys on day 0.

Degarelix 240 mg subcutaneously and bicalutamide 50 mg oral once daily for 2 weeks were started on the same day of new patient consultation (day 0). The radiologist felt that it would be quite difficult to insert a nephrostomy tube. During the multidisciplinary round, the urologist concluded that ADT generally would not work very fast and he intended to put a nephrostomy tube after seeing him. Partly to monitor the response and if possible to avoid an invasive procedure, a repeat CT was performed on day 10 post-ADT. The tumour had decreased in size to 7.1 × 5.6 cm (Fig. 3), and the left renal collecting system was no longer distended (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Computerized tomography scan at the level of prostate on day 10.

Fig. 4.

Computerized tomography scan at the level of kidneys on day 10.

Upper endoscopy did not show any specific stomach or duodenal lesions. Serum creatinine, which was monitored daily in the first week, normalized to below 130 umol/L on day 18. The PSA fell to 11 ug/L on day 18, 2.8 ug/L on day 28, and 0.5 ug/L on day 53. Testosterone was measured on day 28 and already achieved <20 ng/dL (0.69 nmol/L). He then received monthly maintenance doses of degarelix 80 mg subcutaneously.

Discussion

Degarelix was chosen as the treatment for this patient due to its rapid onset of action and lack of flare. Klotz and colleagues made these observations in the CS21 study, a 12-month open-label randomized study on the use of degarelix 240 mg for 1 month then maintenance 80 or 160 mg versus 7.5 mg leuprolide monthly in different stages of prostate cancer.1 Three days after starting treatment, the median testosterone levels were ≤0.5 ng/mL in 96.1% and 95.5% of patients in the degarelix 240/80 mg and 240/160 mg groups, respectively. Some patients in the leuprolide group had testosterone surge; the median testosterone levels increased by 65% from baseline by day 3 (6.30 ng/mL). Of the 201 patients in the leuprolide group, 23 (11%) received concomitant bicalutamide for flare protection at the start of treatment. Of the 178 patients in the leuprolide group who did not receive bicalutamide, 144 (81%) had a surge in testosterone (defined as a testosterone increase of ≥15% from baseline, on any 2 days during the first 2 weeks). In patients who received bicalutamide, 17/23 (74%) had a testosterone surge. PSA was suppressed significantly more rapidly by degarelix at day 14 and 28.

There are other potential advantages of degarelix over LHRH analog. Firstly, compared to leuprolide, it provides a better control of the bone formation marker serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in patients with metastatic disease.2 Secondly, Pickles and colleagues described the problem of incomplete testosterone suppression with LHRH agonists; the risk of a breakthrough >32 ng/dL (1.1 nmol/L) was 6.6%, and >50 ng/dL (1.7 nmol/L) was 3.4%.3 Repeated breakthroughs occurred in 16% of patients. The 5-year biochemical no evidence of disease (bNED) duration was inferior in those with breakthroughs of 1.1 to 1.7 nmol/L versus those without (58% vs. 73%, respectively; p = 0.048). Tombal and colleagues also reported that about 5% to 17% patients on LHRH agonists fail to achieve a castrate testosterone of 50 ng/dL (1.7 nmol/L) or less.4 These are clinically relevant as there is a relationship between testosterone suppression and androgen-independent progression; breakthrough testosterone increases predict decreased progression-free survival (PFS).5 Lastly, the extension study (CS21A) showed that follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) suppression was better with degarelix.6

The disadvantages of degarelix include a 40% rate of injection site reactions,1 cost and inconvenience to patients and staff due to the monthly injection requirement. Table 1 summarizes the current indications for LHRH antagonists. Our case illustrates the advantages of degarelix. In retrospect, the lack of flare with degarelix obviates the need of anti-androgen supplements in our case.

Table 1.

LHRH antagonists are preferred to LHRH agonists in these cases

|

LHRH: luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; PCa: prostate cancers; PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

There are currently no long-term data on survival differences between therapy with degarelix and LHRH agonists. The number of deaths in CS21 is too small to draw any definite conclusions. The published report of CS21A has a median 27.5 month follow-up only.6 However, this is a 5-year extension to the pivotal trial and is ongoing to investigate the long-term safety and efficacy of degarelix.

Conclusion

In emergency situations like spinal cord compression, the lack of flare reaction and rapid response of testosterone within 3 days are distinct advantages over LHRH analogs. Our case illustrates that degarelix can avoid more invasive procedures, like nephrostomy tube insertion or Foley catheterization in patients with urinary obstruction. LHRH antagonists are particularly useful in urgent and emergency situations. It is the preferred choice in these circumstances.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Klotz L, Boccon-Gibod L, Shore ND, et al. The efficacy and safety of degarelix: a 12-month, comparative, randomized, open-label, parallel-group phase III study in patients with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:1531–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tombal B, Miller K, Boccon-Gibod L, et al. Additional analysis of the secondary end point of biochemical recurrence rate in a Phase 3 trial (CS21) comparing degarelix 80 mg versus leuprolide in prostate cancer patients segmented by baseline characteristics. Eur Urol. 2010;57:836–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickles T, Hamm J, Morris WJ, et al. Incomplete testosterone suppression with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists: does it happen and does it matter? BJU Int. 2012;110(11 Pt B):E500–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tombal B, Berges R. How good do current LHRH agonists control testosterone? Can this be improved with Eligard®? Eur Urol. 2005;4S:30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morote J, Orsola A, Planas J, et al. Redefining clinically significant castration levels in patients with prostate cancer receiving continuous androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol. 2007;178:1290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford ED, Tombal B, Kurt Miller K, et al. A phase III extension trial with a 1-arm crossover from leuprolide to degarelix: comparison of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and antagonist effect on prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:889–97. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]