Abstract

Context

Although suicide is the third leading cause of death among US adolescents, little is known about the prevalence, correlates, or treatment of its immediate precursors, adolescent suicidal behaviors (i.e., suicide ideation, plans, and attempts).

Objectives

To estimate lifetime prevalence of suicidal behaviors among US adolescents and associations of retrospectively-reported temporally primary DSM-IV disorders with the subsequent onset of suicidal behaviors.

Design

Dual-frame national sample of adolescents from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A).

Setting

Face-to-face household interviews with adolescents and questionnaires with parents.

Participants

6,483 adolescents (ages 13–18 years) and parents.

Main outcome measures

Lifetime suicide ideation, plans, and attempts.

Results

The estimated lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts among NCS-A respondents is 12.1%, 4.0% and 4.1%. The vast majority of adolescents with these behaviors meet lifetime criteria for at least one DSM-IV mental disorder assessed in the survey. Most temporally primary (based on retrospective age-of-onset reports) fear/anger, distress, disruptive behavior, and substance disorders significantly predict elevated odds of subsequent suicidal behaviors in bivariate models. The most consistently significant associations of these disorders are with suicide ideation, although a number of disorders also predict plans and both planned and unplanned attempts among ideators. Most suicidal adolescents (>80%) receive some form of mental health treatment. In most cases (>55%) treatment starts prior to onset of suicidal behaviors but fails to prevent these behaviors from occurring.

Conclusions

Suicidal behaviors are commonly occurring among US adolescents, with rates that approach those of adults. The vast majority of youth with suicidal behaviors have pre-existing mental disorders. The disorders most powerfully predicting ideation, though, are different from those most powerfully predicting conditional transitions from ideation to plans and attempts. These differences suggest that distinct prediction and prevention strategies are needed for ideation, plans among ideators, planned attempts, and unplanned attempts.

Suicidal behaviors are among the leading causes of death worldwide, especially among adolescents and young adults.1–4 Despite the scope and seriousness of the problem, relatively little is known about the prevalence, correlates, or treatment of suicidal behavior (i.e., suicide ideation, plans and attempts) among US adolescents, as nationally representative studies of this problem are rare. Although some prior studies have reported on these aspects of adolescent suicidal behavior5–8 and death,9–11 virtually all of them were based on small regional samples, limiting the generality of findings and precluding fine-grained analyses. Comprehensive national data on suicidal behavior among adolescents are needed to improve our understanding of the nature of this perplexing and devastating problem, arm clinicians with information about risk profiles, and help inform decisions about promising prevention targets.

The current report presents data on the epidemiology of adolescent nonlethal suicidal behaviors from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), the first national survey of US adolescents to assess a wide range of DSM-IV mental disorders and suicidal behaviors using fully-structured diagnostic interviews. Several recent studies have reported on the NCS-A design,12, 13 measures,14, 15 the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders,16–18 and 12-month prevalence and treatment of suicidal behaviors.19 In the current report, we present new data on lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset of suicidal behaviors as well as information on correlations with temporally primary mental disorders and treatment.

METHOD

Sample

The NCS-A is a survey of 10,148 adolescents (ages 13–17 at the time of selection, although some respondents turned 18 before interview) in the continental United States completed in conjunction with the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).20 NCS-A design and field procedures are reported in detail elsewhere.12–15 The NCS-A used a dual-frame sample composed of (a) a household sub-sample of adolescents (n = 904) selected from NCS-R households and (b) a school sub-sample of adolescents (n = 9,244) selected from schools (day and residential schools of all types, probabilities proportional to size) in the same nationally-representative counties as those in the NCS-R. The overall response rate was 82.9%.

One parent or parent surrogate (subsequently referred to as “parents”) of each adolescent provided written informed consent and adolescents provided written informed assent before adolescent interviews. Parents also completed self-administered questionnaires (SAQ) about the adolescent’s mental health. The SAQ response rate was 82.5–83.7% in the household-school samples. This report focuses on the 6,483 adolescent-parent pairs with complete data. Use of this sub-sample reduces precision of estimates compared to analyses based on the full sample, but eliminates the bias introduced by having missing parent reports on adolescent disorders.

Each parent and adolescent was paid $50 for participation. All study procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. Completed cases were weighted for within-household probability of selection (for the household sub-sample) and residual discrepancies between sample and population on demographic-geographic variables. Weighting procedures are described elsewhere.12, 13 Adolescents in the weighted NCS-A parent-adolescent sample are very similar to the population of US adolescents on a wide range of socio-demographic/geographic variables.12, 13

Measures

Suicidal behaviors

Suicidal behaviors were assessed using a modified version of the Suicidal Behavior Module of the CIDI.21, 22 This module assesses lifetime occurrence and age-of-onset (AOO) of suicide ideation (“You seriously thought about committing suicide”) and, among respondents who reported lifetime ideation, suicide plans (“You made a plan for committing suicide”) and suicide attempts (“You attempted suicide”). In order to examine transitions among behaviors, we focus not only on predictors of lifetime suicide attempts but also predictors of lifetime suicide ideation, lifetime suicide plans among ideators, and lifetime attempts among ideators with and without a plan.

DSM-IV mental disorders

All adolescents completed a modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a fully-structured diagnostic interview administered by trained lay interviewers16, 21 modified for administration to adolescents.15 The disorders examined here were organized into four broad categories based on the results of an exploratory factor analysis reported elsewhere:23 fear and anger disorders (panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia, intermittent explosive disorder [IED]), distress disorders (separation anxiety disorder [SAD], post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], major depressive disorder and/or dysthymia [MDD/DYS], and generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]), disruptive behavior disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder [CD], and eating disorders [including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder]), and substance abuse (alcohol and illicit drug abuse). We also assessed bipolar disorder (I or II). Parent reports were also obtained and were combined with adolescent reports to derive DSM-IV diagnoses for the four disorders shown in prior research to benefit most from inclusion of parental reports: MDD/DYS, ADHD, ODD, and CD.24, 25 Adolescent and parent reports were combined using an “or” rule at the symptom level. An NCS-A clinical reappraisal study showed good concordance between diagnoses based on the CIDI and SAQ and independent clinical diagnoses in a sub-sample of NCS-A parent-adolescent pairs14 based on blinded administration of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL).14, 26

Socio-demographics

The CIDI assessed a number of socio-demographic variables considered here: sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), parental education (less than high school graduation, high school or GED, some post-secondary education, college degree), birth order (first, last, other), number of siblings (0,1,2,3+), and number of biological parents living with the adolescent (0,1,2). Information was collected in the surveys to date transitions in time-varying variables (e.g., respondent age at birth of siblings and at parental death or divorce), allowing us to redefine these variables for each year of the respondent’s life as time-varying predictors of onset of suicidality.

Treatment

Lifetime history of treatment for emotional or behavioral problems was assessed using questions from the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents.27, 28 Entry question asked respondents if they (for adolescent self-reports) or their child (for parent reports) ever “received services” for problems with “emotions or behavior or alcohol of drug use” from each of 11 different types of professionals or settings. Responses were collapsed into six treatment sectors: (1) mental health specialty (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist), (2) general medical (e.g., primary care physician, nurse, pediatrician), (3) human services (e.g., counselor, crisis hotline, religious/spiritual advisor), (4) complementary-alternative medicine (CAM; e.g., self-help group, support group, other healer), (5) juvenile justice (e.g., probation or juvenile corrections officer or court counselor), and (6) school services (e.g., special school for emotional/behavioral problems, school counseling, school nurse). No information was obtained about the content of the “services” received, which means that the characterization of services as “treatment” can be called into question with regard to human services, juvenile justice, and school services.

Statistical analysis

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate lifetime prevalence of suicidal behaviors, mental disorders, and treatment. Discrete-time survival analysis with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function was used to examine associations of temporally primary (based on retrospective AOO reports) mental disorders and subsequent first onset of suicidality.29 Time was modeled as a separate dummy predictor variable for each year of life up to age at interview or age at onset of the outcome, whichever came first. Survival coefficients their standard errors were exponentiated and reported as odds-ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. Results of both bivariate and multivariate models are reported to provide information on both gross and net associations of disorders with suicidal behaviors.

Multivariate survival models either assumed additivity (in predicting logits) or included non-additive associations among comorbid mental disorders. The latter models included a separate dummy predictor variable for each disorder (“type dummies”) and dummy predictor variables for number of disorders (“number dummies”). Relative-odds of suicidal behaviors associated with a given comorbid cluster (compared to respondents with no disorders) correspond to the product of the type dummies and the number dummy for the respondent’s number of disorders. For example, the relative-odds of suicidal behaviors among respondents with a given set of three comorbid disorders would be the product of the three type ORs for those particular disorders multiplied by the three-disorder number dummy, where the latter was assumed to be constant for all respondents with any combination of exactly three or more comorbid disorders. This means that the ORs associated with the number dummies can be interpreted as multiplicative deviations from the associations of comorbid disorder clusters with the outcomes expected based on an additive model (i.e., a model with type dummies but no number dummies).30

The Taylor series method31 was used to estimate standard errors in the SUDAAN software system32 to adjust for sample weighting-clustering. Multivariate significance was examined using Wald χ2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated using two-sided .05-level tests. Individually significant coefficients were interpreted only if the equation in which they were estimated was significant as a whole in a multivariate test; an approach that minimizes the problem of false positives due to multiple comparisons while avoiding the problem of low power to detect true associations of moderate magnitude that is introduced by more conservative methods (e.g., Bonferroni corrections).33 Model comparisons were made using the Akaike Information Criterion.34

RESULTS

Prevalence and age-of-onset of suicidal behaviors

Lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts are 12.1%, 4.0%, and 4.1%, respectively. (Table 1) One-third (33.4%) of ideators go on to develop a suicide plan and 33.9% make an attempt. The proportions of ideators who go on to make an attempt are 60.8% of those with a plan compared to 20.4% of those without a plan, resulting in roughly 60% of first attempts being planned (57% among boys and 66% among girls) and the other 40% unplanned. All of these prevalence estimates are higher among girls than boys, with the exception of the proportion of ideators who go on to develop a plan and the proportion of attempts that are planned vs. unplanned.

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of adolescent suicidality in the NCS-A (n = 6,483)

| In the total sample

|

Among lifetime ideators

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation | Plan | Attempt | Plan | Attempt | Attempt among those with a plan | Attempt among those with no plan | |

| %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | %1 (SE) | |

|

|

|

||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 15.3* (1.2) | 5.1* (0.8) | 6.2* (0.9) | 33.3 (4.1) | 40.6* (3.9) | 69.9* (4.6) | 25.9* (5.8) |

| Male | 9.1 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.5) | 33.4 (5.2) | 23.3 (4.9) | 46.3 (9.8) | 11.7 (2.8) |

| Total | 12.1 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.6) | 33.4 (3.2) | 33.9 (3.7) | 60.8 (4.8) | 20.4 (4.1) |

| (n)1 | (6,483) | (6,483) | (6,483) | (717) | (717) | (203) | (514) |

Significant gender difference at the .05 level, two-sided test

Denominator n for each column

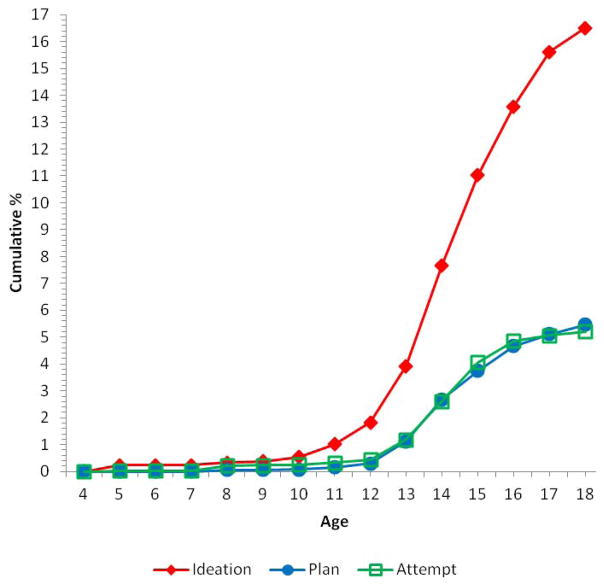

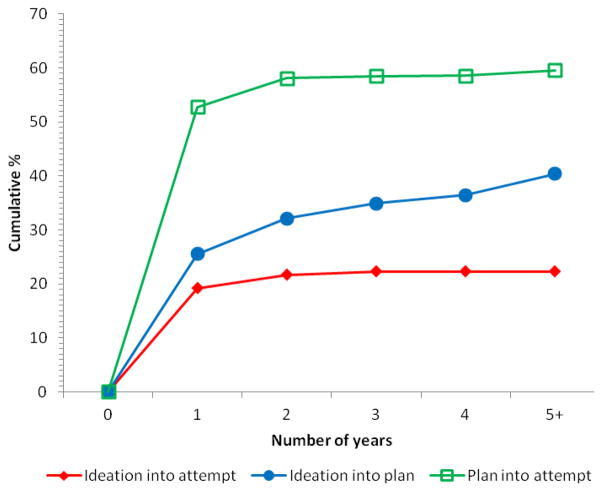

AOO curves show that lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation is very low (<1%) through age 10, then increases slowly through age 12, and more rapidly between ages 12 and 17. (Figure 1) Prevalence of plans and attempts, in comparison, remains very low (<1%) through age 12 and then increases in roughly linear fashion through age 15 and more slowly until age 17. Speed-of-transition curves show that the vast majority of adolescent transitions from ideation to plan (63.1%) and from ideation to attempt (86.1%) occur within the first year of onset of ideation. (Figure 2) The vast majority (88.4%) of adolescent transitions from plan to attempt occur within the year of developing the plan.

Figure 1.

Age of onset curves of suicidal behaviors

Values are all 0.0 for years 1–4

Figure 2.

Speed of transition across suicidal behaviors

Socio-demographic correlates

Girls have significantly elevated odds of lifetime suicide ideation (OR=1.7) and attempt (OR=2.9) and, among ideators, of making an unplanned attempt (OR=3.7), but do not differ significantly from boys either in the transition from ideation to a plan (OR=1.0) or transition from plan to attempt (OR=1.7). (Table 2) Non-Hispanic Blacks have significantly lower odds of attempts (OR=0.3) than Non-Hispanic Whites, which can be traced to significantly lower odds of ideation (OR=0.5) in conjunction with insignificantly lower conditional odds of plans among ideators (OR=0.7) and attempts among both planners (OR=0.4) and ideators without a plan (OR=0.4). Hispanics and other race/ethnic groups, in comparison, do not differ significantly from Non-Hispanic Whites in any of these odds.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic predictors of lifetime suicidality1

| In the total sample

|

Among lifetime ideators

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation | Attempt | Plan | Attempt2 | Attempt among those with a plan | Attempt among those with no plan | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.7* (1.4–2.1) | 2.9* (1.8–4.8) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 2.4* (1.4–4.2) | 1.7 (0.6–4.6) | 3.7* (1.7–8.2) |

| Male | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| χ21 | 36.1* | 18.5* | 0.0 | 10.1* | 1.1 | 11.0* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.5* (0.3–0.7) | 0.3* (0.2–0.6) | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) | 0.3 (0.0–3.0) | 0.4 (0.1–1.7) |

| Hispanic | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.7 (0.8–3.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | 2.2 (0.8–5.6) | 2.8 (0.6–13.1) | 2.1 (0.6–6.9) |

| Other | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.7 (0.2–1.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 1.0 (0.2–4.4) | 0.8 (0.1–4.7) | 0.7 (0.1–4.1) |

| χ23 | 36.8* | 22.2* | 5.1 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Highest level of parental education | ||||||

| Less than HS | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.0 (0.4–2.9) | 1.9 (0.9–4.2) | 1.0 (0.3–3.2) | 0.3 (0.1–1.3) | 1.6 (0.4–6.3) |

| HS | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 2.0* (1.0–3.9) | 1.9 (1.0–3.9) | 1.7 (0.8–4.0) | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) | 1.8 (0.5–6.3) |

| Some college | 1.4* (1.1–1.9) | 3.0* (2.0–4.6) | 2.0 (1.0–4.2) | 2.2* (1.1–4.4) | 1.5 (0.5–4.1) | 3.4* (1.4–8.4) |

| College graduate | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| χ23 | 8.1* | 37.9* | 5.1 | 8.6* | 5.2 | 8.5* |

| Birth order | ||||||

| Oldest | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 1.0 (0.5–2.2) | 2.0 (0.5–8.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) |

| Youngest | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 1.7 (0.7–4.0) | 0.6 (0.3–1.6) | 2.7 (0.5–14.8) | 0.1* (0.0–0.4) |

| Other | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| χ22 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 11.7* |

| Number of siblings | ||||||

| None | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1 | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.2 (0.0–1.1) | 0.3 (0.0–1.7) |

| 2 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.3 (0.1–1.0) | 0.3 (0.0–1.9) | 0.1* (0.0–0.9) |

| 3+ | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 1.1 (0.3–3.7) | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | 1.1 (0.1–8.2) | 0.1* (0.0–0.5) |

| χ23 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 8.5* | 9.7* |

| Number of biological parents living with adolescent | ||||||

| None | 2.8* (2.0–3.9) | 4.0* (2.3–7.0) | 1.0 (0.5–2.1) | 3.0* (1.4–6.2) | 7.1* (2.6–19.6) | 3.4* (1.1–9.8) |

| 1 | 1.8* (1.2–2.7) | 2.0* (1.1–3.8) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.9 (0.3–3.1) | 1.3 (0.5–3.3) |

| 2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| χ22 | 43.0* | 30.4* | 4.0 | 10.4* | 17.4* | 5.5 |

| χ213 | 255.6* | 336.2* | 29.4* | 119.6* | 50.0* | 34.2* |

| (n)3 | (6,483) | (6,483) | (717) | (717) | (203) | (514) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival models with person-year the unit of analysis, a logistic link function, and person-year defined as a separate dummy predictor variable for each year of life.

An additional control was included in this model for lifetime suicide plan

Denominator n for each column

The odds of attempt are elevated among youths with a parent who graduated from high school (OR=2.0) or completed some college (OR=3.0) compared to those with either more (i.e., college graduates) or less (i.e., did not graduate from high school) education. These associations are due to: significantly elevated odds of ideation among respondents whose parents having some college (OR=1.4), non-significantly elevated conditional odds of a plan (OR=1.9–2.0) and planned attempt (OR=1.3–1.4) among respondents whose parents completed high school or some college with, and elevated odds of unplanned attempt (significant only for the offspring of parents with some college) in these two sub-samples. Birth order and number of siblings are related only to one aspect of suicidality: significantly reduced odds of unplanned attempt among youngest children and those with two or more siblings (OR=0.1). Finally, a significant relationship exists between living with 0 (OR=4.1) or 1 (OR=2.0) versus both biological parents and suicide attempt due to significantly elevated odds of ideation (OR=2.8–1.8) and, among youth living with no biological parents, of both planned (OR=6.2) and unplanned (OR=3.7) attempts.

Prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents with suicidal behaviors

The vast majority of adolescents with a lifetime history of suicide ideation (89.3%) and attempt (96.1%) meet lifetime criteria for at least one of the 15 DSM-IV/CIDI disorders considered here. (Table 3) The prevalence of each disorder is elevated in virtually all sub-samples of youths with suicidal behaviors, with 78.7% of these differences statistically significant at the .05 level. The most prevalent lifetime disorder among suicidal adolescents is MDD/DYS followed by specific phobia, ODD, IED, substance abuse, and CD. The prevalence of mental disorders generally increases with increasing severity of suicidal behaviors (i.e., suicide ideation < suicide plan < suicide attempt), although SAD shows the opposite pattern.

Table 3.

Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI mental disorders among respondents with versus without lifetime suicidality1

| In the total sample

|

Among lifetime ideators

|

No lifetime suicidality3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation | Plan | Attempt | Planned attempt2 | Unplanned attempt | ||

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| I. Fear/anger disorders | ||||||

| Specific phobia | 36.8* (2.7) | 39.0* (6.2) | 44.3* (6.3) | 40.7* (8.8) | 49.6* (12.8) | 17.6 (1.0) |

| Panic disorder and/or agoraphobia | 10.1* (1.8) | 10.6* (2.7) | 10.4 (3.0) | 10.8 (3.6) | 9.8 (4.1) | 4.0 (0.5) |

| Social phobia | 19.9* (2.9) | 16.2* (2.8) | 25.6* (7.0) | 17.7* (4.3) | 37.5 (15.0) | 7.0 (0.5) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 29.4* (2.6) | 35.7* (5.5) | 35.2* (7.0) | 42.1* (8.4) | 24.9 (8.8) | 11.5 (0.7) |

| II. Distress disorders | ||||||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 11.9 (2.1) | 8.9 (2.7) | 7.0 (2.2) | 3.9 (1.6) | 11.5 (4.8) | 7.0 (0.5) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 16.1* (2.1) | 27.9* (4.3) | 25.7* (5.4) | 34.2* (5.9) | 13.0 (6.2) | 3.1 (0.3) |

| Major depressive disorder or dysthymia | 56.8* (3.4) | 69.7* (4.7) | 75.7* (4.7) | 76.7* (6.7) | 74.3* (8.2) | 13.3 (0.9) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 8.4* (1.7) | 10.3 (3.1) | 9.2* (3.5) | 11.2 (5.0) | 6.2 (2.7) | 1.6 (0.3) |

| III. Disruptive behavior disorders | ||||||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 16.3* (2.6) | 19.0* (5.4) | 21.5* (4.6) | 23.5 (8.0) | 18.5 (6.0) | 7.0 (0.6) |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder | 34.4* (3.9) | 41.6* (5.0) | 50.0* (8.0) | 51.5* (6.1) | 47.8* (13.9) | 9.6 (0.8) |

| Conduct disorder | 20.2* (4.4) | 22.8* (5.3) | 33.5* (10.2) | 26.9* (7.6) | 43.3* (13.8) | 5.0 (0.7) |

| Any eating Disorder | 15.8* (2.8) | 11.9 (3.7) | 26.7* (6.9) | 15.3 (5.9) | 43.7* (14.4) | 4.0 (0.6) |

| IV. Substance abuse4 | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 18.4* (2.0) | 28.6* (5.3) | 24.3* (4.4) | 34.4* (7.9) | 9.2 (3.5) | 4.6 (0.5) |

| Illicit drug abuse | 27.4* (2.9) | 28.0* (4.5) | 34.7* (6.1) | 27.5* (6.0) | 45.3* (13.9) | 6.4 (0.6) |

| V. Other disorders | ||||||

| Bipolar I or II | 9.1* (1.8) | 11.9* (4.2) | 13.2* (4.3) | 18.6* (6.5) | 5.2 (2.5) | 2.2 (0.3) |

| Any disorder | 89.3* (1.3) | 93.6* (2.2) | 96.1* (1.8) | 96.7* (2.5) | 95.2* (2.8) | 49.5 (1.3) |

| (n)5 | (717) | (203) | (196) | (112) | (84) | (5,766) |

Significant difference in prevalence from respondents who had no history of suicidality at the .05 level, two-sided test

The sample was restricted to adolescents with the outcomes defined in the column headings.

The sample was restricted to adolescents that had a lifetime plan.

The sample was restricted to adolescents who never had any suicidality

With or without a history of dependence

Denominator n for each column

Associations of temporally primary lifetime mental disorders with suicide attempts

Discrete-time survival analysis was used to examine associations of temporally primary lifetime mental disorders with subsequent first onset of suicide attempt. Results of bivariate models (i.e., including only one disorder at a time) suggest that 13 of the 15 lifetime DSM-IV disorders examined are associated with significantly elevated odds of subsequent suicide attempt. (Table 4) Panic/agoraphobia and SAD are the exceptions. Significant ORs are 4.5–7.4 for disruptive behavior disorders, 4.1–12.3 for significant distress disorders, 2.8–4.8 for substance disorders, and 2.5–3.5 for significant fear/anger disorders. The OR for bipolar disorder is 8.8. ORs become smaller in an additive multivariate survival model that includes all 15 mental disorders as predictors. The only significant positive predictors of suicide attempt in this additive model are PTSD (OR=3.3), MDD/DYS (OR=6.2), ODD (OR=2.1), eating disorder (OR=3.2), and bipolar disorder (OR=2.9). Interestingly, there is a significant protective effect for SAD (OR=0.3).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate associations (odds-ratios) of temporally primary DSM-IV/CIDI disorders with first onset of lifetime suicide attempt in the total sample (n = 6,483)1

| Bivariate model2

|

Multivariate model2

|

|

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| I. Fear/anger disorders | ||

| Specific phobia | 2.5* (1.7–3.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Panic disorder and/or agoraphobia | 1.9 (0.9–4.3) | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) |

| Social phobia | 2.5* (1.4–4.3) | 0.8 (0.4–2.0) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 3.5* (1.7–7.5) | 1.7 (0.8–3.6) |

| II. Distress disorders | ||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 0.8 (0.3–1.7) | 0.3* (0.1–0.7) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 7.3* (3.7–14.4) | 3.3* (2.0–5.5) |

| Major depressive disorder or dysthymia | 12.3* (8.0–19.0) | 6.2* (3.8–10.0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 4.1* (1.4–11.8) | 0.9 (0.2–3.4) |

| III. Disruptive behavior disorders | ||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 4.8* (2.9–8.0) | 1.9 (1.0–3.7) |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder | 7.2* (4.0–12.8) | 2.1* (1.2–3.6) |

| Conduct disorder | 4.5* (2.6–7.9) | 1.0 (0.5–2.2) |

| Any eating Disorder | 7.4* (4.1–13.6) | 3.2* (1.5–7.0) |

| IV. Substance abuse3 | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 2.8* (1.2–6.3) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) |

| Illicit drug abuse | 4.8* (2.5–9.1) | 1.3 (0.5–3.3) |

| V. Other disorders | ||

| Bipolar I or II | 8.8* (3.8–20.1) | 2.9* (1.0–7.9) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival models with person-year the unit of analysis, a logistic link function, and person-year defined as a separate dummy predictor variables for each year of life. Both models control for the socio-demographic variables in Table 2. Lifetime predictor disorders are coded as present only if their AOO is less than or equal to the age when the respondent made his or her first suicide attempt.

The bivariate model includes only one mental disorder in each equation, whereas the multivariate model includes all 15 mental disorders in the same equation. The addition of the 15 disorders to the predictor set in the multivariate model improves on the socio-demographic model in Table 2 (Akaike Information Criterion [AIC] = 2862.4 for the socio-demographic model and 2354.8 for the model that added the 15 mental disorders; the model with the lower AIC being the preferred model).

With or without a history of dependence

The additive multivariate survival model implicitly assumes the odds of suicide attempt among respondents with comorbid disorders equal the product of ORs associated with individual disorders. However, a non-additive model that includes additional number-of-disorder dummies for exactly two and three or more disorders fits the observed data better than the additive model (AIC=2354.8 for the additive model and 2340.4 for the non-additive model, with the preferred model being the one with the lower AIC). (Table 5) A comparison of coefficients in the two models shows five of the same six disorders are significant but with positive ORs consistently lower in the non-additive model due to odds of attempted suicide being 1.5 times the product of the ORs of the component disorders among respondents with two comorbid disorders and 3.4 times that product among respondents with three or more comorbid disorders.

Table 5.

Multivariate associations (odds-ratios) of type and number of temporally primary (based on retrospective reports) with subsequent first onset of lifetime suicidality1

| Lifetime DSM-IV disorders | In the total sample

|

Among lifetime ideators

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation | Attempt | Plan | Attempt with a control for plan2 | Attempt with interactions by plan2 | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

||||

| Fear/anger disorders | |||||

| Specific phobia | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| Panic disorder and/or agoraphobia | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 0.9 (0.3–2.9) | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) |

| Social phobia | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 1.0 (0.3–3.6) | 1.0 (0.3–3.9) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 1.5* (1.0–2.1) | 1.4 (0.7–3.0) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 1.6 (0.7–3.4) | --- |

| Intermittent explosive disorder with a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 4.2* (1.7–10.0) |

| Intermittent explosive disorder without a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.5 (0.1–1.7) |

| Distress disorders | |||||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.3* (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | --- |

| Separation anxiety disorder with a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.1* (0.0–0.3) |

| Separation anxiety disorder without a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.0 (0.4–2.9) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1.7* (1.2–2.4) | 2.6* (1.5–4.5) | 2.0 (0.9–4.2) | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | 1.6 (0.7–3.7) |

| Major depressive disorder or dysthymia | 4.1* (3.0–5.5) | 4.3* (2.3–8.3) | 2.0* (1.1–3.8) | 2.4* (1.1–5.2) | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 1.0 (0.3–3.1) | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.8 (0.2–2.7) | 0.8 (0.2–2.9) |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | |||||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 2.1 (0.9–4.8) | 2.5* (1.1–5.5) |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder | 1.6* (1.1–2.3) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) |

| Conduct disorder | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 3.2* (1.6–6.3) | --- |

| Conduct disorder with a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) |

| Conduct disorder without a Suicide Plan | --- | --- | --- | --- | 8.0* (3.5–18.3) |

| Any eating disorder | 1.5* (1.1–2.2) | 2.8* (1.4–5.4) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 4.5* (1.8–11.2) | 5.3* (2.0–14.0) |

| Substance abuse3 | |||||

| Alcohol abuse | 2.5* (1.5–4.1) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 0.4* (0.2–0.8) | 0.3* (0.1–1.0) |

| Illicit drug abuse | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 1.3 (0.6–2.9) | 0.4* (0.2–0.8) | 1.0 (0.4–2.3) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) |

| Other Disorders | |||||

| Bipolar I or II | 1.7* (1.0–2.8) | 2.6* (1.1–6.0) | 1.9 (0.8–4.9) | 2.3 (0.8–6.4) | 2.2 (0.7–7.2) |

| Number of disorders | |||||

| 2 disorders | 1.9* (1.3–2.9) | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) |

| 3+ disorders | 1.9* (1.0–3.7) | 3.4* (1.0–11.9) | 2.3 (0.7–7.4) | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) |

| Suicide plan | --- | --- | --- | 5.3* (3.2–8.8) | 5.0* (2.4–10.5) |

| (n)4 | (6,483) | (6,483) | (717) | (514) | (203) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Results are based on discrete-time survival models. Models control for all the demographic variables from Table 2 and person-years (each year coded as a dichotomous dummy, starting from year 4).. Time-varying disorders were not time-lagged (turns on the year of onset for the disorder).

A dummy predictor variable for having a plan was included in both models. In the model that merely controlled for plan, this was the only additional predictor, which means that it was implicitly assumed that the ORs of temporally primary disorders predicting subsequent attempt were the same for planned and unplanned attempts. In the model that also included interactions, subgroup coding was used to estimate ORs of disorders separately with planned and unplanned attempts for the subset of disorders in which the difference between these two ORs was found to statistically significant and stable.

With or without a history of dependence

Denominator n for each column.

We used the same non-additive model to predict lifetime ideation in the total sample and lifetime plans and attempts among ideators in an effort to decompose the associations of temporally prior mental disorders with suicide attempts through the more proximal outcomes. Results show that prior mental disorders are most strongly associated with suicide ideation (12 disorders have ORs greater than 1.0, 7 of them significant, and the ORs of comorbidity significantly greater than 1.0). Conditional associations of mental disorders with suicide plans among ideators are weaker and less consistent (6 disorders have ORs greater than 1.0, 1 of them significant, but with the OR for illicit drug abuse significantly less than 1.0). Conditional associations of mental disorders with attempts among ideators controlling for plans are somewhat weaker and less consistent than with plans (9 disorders having ORs greater than 1.0, 3 of them significant, but with the OR for alcohol abuse significantly less than 1.0). Having a plan, in comparison, is strongly associated with elevated odds of attempt among ideators (OR=5.3).

We also found significant global interactions between type-number of disorders and plans predicting attempts among ideators (χ217=65.0, p<.001). However, multicollinearity due to high comorbidity among respondents with suicide plans made it impossible to estimate a model with all 17 type-number coefficients separately for ideators with and without a plan. We were able to estimate a stable model, though, by constraining ORs for particular types-numbers of disorders to be the same in predicting both planned and unplanned attempts unless the interaction of the predictor with plans in the pooled model was significant at the .05 level and had an estimated variance inflation factor (VIF; a diagnostic test suggesting that a regression coefficient might be affected by multicollinearity) less than 10.0. The final model constrained in this way included interactions of three disorders with plans: IED, SAD, and CD. This model fits the data better than a model with no interactions between disorders and plans (AIC=1041.9 for the model with interactions versus 1083.6 without interactions). Only half of the 12 disorders with the same ORs predicting planned and unplanned attempts are greater than 1.0, two of them significant (OR=2.5 for ADHD and 5.3 for eating disorders), and one other OR is significantly less than 1.0 (OR=0.3 for alcohol abuse). Two of the three disorders with ORs that differ in predicting planned and unplanned attempts are significant only in predicting planned attempts (OR=4.2 for IED and 0.1 for SAD). The other is significant only in predicting unplanned attempts (OR=8.0 for CD).

It is instructive to trace out the significant associations of type-number of disorders with suicide attempts in the total sample through more proximal outcomes (i.e., ideation, plans among ideators, and attempts among ideators with/without a plan). All four of the disorders with significant ORs greater than 1.0 predicting suicide attempt in the total sample (PTSD, MDD/DYS, eating disorders, bipolar disorder) have significant ORs predicting ideation (1.7–4.1). This is the only significant OR for two of these four disorders (PTSD and bipolar disorder), although ORs of these disorders with other intermediate outcomes are all elevated (1.2–2.2). In the case of MDD/DYS, in comparison, most of the ORs with intermediate outcomes also are significantly greater than 1.0, although the OR with ideation (4.1) is higher than the ORs with the intermediate outcomes (all of which are 2.0–2.4). In the case of eating disorders, the OR is significantly elevated predicting ideation (1.5), insignificant predicting plan among ideators (0.6), and significantly elevated predicting attempt among ideators controlling for a plan (4.5). The only significant component OR in the case of SAD, the one disorder associated with significantly reduced odds of suicide attempt in the total sample (0.3), is with attempt among planners (0.1). The elevated ORs of comorbidity with suicide attempts in the total sample, finally, are due to significant ORs with ideation (1.9) and insignificantly elevated ORs with plan among ideators (1.5–2.3).

Treatment of suicidal adolescents

Most adolescents with suicide ideation (80.2%), plan (87.5%), and attempt (94.2%) have received some form of treatment, although it is important to remember the caution raised above in the section on measures that some proportion of the “services” received in the human services, juvenile justice, and school services sectors might not have qualified as “treatment.” (Table 6) The most common form of treatment was from a mental health specialist (66.4–86.2% across outcomes), followed by school-based services (40.6–68.0%), general medical treatment (25.8–41.1%), human services (21.1–40.2%), CAM (17.3–25.1%), and from the juvenile justice system (10.2–17.7%).

Table 6.

Lifetime treatment among respondents with lifetime suicidality1

| In the total sample

|

Among lifetime ideators

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideation | Plan | Attempt | Planned attempt2 | Unplanned attempt | |

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | |

|

|

|

||||

| I. Percent of lifetime cases that received any lifetime treatment | |||||

| Mental health specialty | 66.4 (2.6) | 72.7 (4.5) | 82.1 (4.3) | 79.4 (5.4) | 86.2 (5.5) |

| General med | 25.8 (2.5) | 34.0 (5.3) | 37.0 (4.4) | 41.1 (8.3) | 30.9 (9.1) |

| Human service | 25.3 (2.8) | 34.0 (5.0) | 32.6 (6.1) | 40.2 (6.6) | 21.1 (7.4) |

| CAM | 19.6 (2.3) | 25.1 (4.2) | 21.9 (4.7) | 25.0 (5.3) | 17.3 (5.8) |

| Juvenile justice | 10.2 (2.1) | 12.6 (3.7) | 16.8 (4.4) | 17.7 (5.2) | 15.4 (5.9) |

| School service | 46.4 (2.4) | 61.9 (5.1) | 57.0 (4.9) | 68.0 (6.0) | 40.6 (11.7) |

| Any treatment | 80.2 (1.8) | 87.5 (2.8) | 94.2 (1.9) | 93.6 (3.0) | 95.1 (2.1) |

| II. Percent of lifetime cases that received treatment before onset of suicidality | |||||

| Mental health specialty | 39.6 (2.7) | 43.2 (4.9) | 48.4 (4.7) | 40.5 (6.8) | 60.2 (10.7) |

| General med | 13.1 (2.1) | 20.5 (5.4) | 21.0 (4.7) | 28.0 (8.0) | 10.7 (4.9) |

| Human service | 12.9 (2.6) | 17.1 (5.0) | 14.7 (4.3) | 17.1 (5.6) | 11.0 (4.6) |

| CAM | 9.2 (1.8) | 13.4 (4.3) | 12.8 (3.9) | 13.4 (5.0) | 11.8 (4.5) |

| Juvenile justice | 1.8 (0.6) | 2.0 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.5) | 5.9 (3.4) |

| School service | 30.6 (2.1) | 43.3 (5.4) | 39.0 (5.3) | 45.5 (8.7) | 29.2 (8.5) |

| Any treatment | 55.3 (3.2) | 61.7 (4.7) | 67.1 (5.7) | 63.0 (5.9) | 73.2 (7.3) |

| III. Percent of lifetime cases that first received treatment in the same year as onset of suicidality | |||||

| Mental health specialty | 12.7 (1.9) | 14.8 (3.8) | 11.8 (3.5) | 12.2 (3.7) | 11.2 (5.1) |

| General med | 5.0 (0.9) | 7.4 (2.6) | 4.9 (1.8) | 3.7 (2.2) | 6.6 (3.1) |

| Human service | 5.4 (1.2) | 10.1 (3.3) | 8.7 (3.0) | 12.4 (4.7) | 3.1 (2.2) |

| CAM | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.1 (2.5) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.7) |

| Juvenile justice | 2.4 (1.0) | 1.3 (0.8) | 2.1 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.7) |

| School service | 5.1 (1.2) | 7.7 (2.7) | 3.8 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.3) | 5.4 (2.7) |

| Any treatment | 13.1 (1.6) | 17.7 (4.2) | 15.2 (3.7) | 18.2 (5.3) | 10.8 (3.7) |

| IV. Percent of lifetime cases that first received treatment after onset of suicidality | |||||

| Mental health specialty | 14.1 (2.0) | 14.7 (5.6) | 22.0 (3.9) | 26.8 (7.9) | 14.8 (5.7) |

| General med | 7.8 (1.3) | 6.0 (2.1) | 11.1 (2.6) | 9.4 (4.3) | 13.6 (5.8) |

| Human service | 7.0 (1.4) | 6.8 (3.1) | 9.2 (3.1) | 10.7 (4.7) | 7.0 (2.7) |

| CAM | 5.9 (1.0) | 7.6 (1.8) | 6.0 (1.8) | 8.3 (2.7) | 2.7 (1.6) |

| Juvenile justice | 6.0 (1.6) | 9.3 (3.3) | 11.0 (3.7) | 13.6 (5.0) | 7.1 (4.4) |

| School service | 10.8 (2.0) | 10.9 (3.3) | 14.2 (3.9) | 19.7 (5.4) | 6.1 (2.6) |

| Any treatment | 11.9 (2.4) | 8.1 (3.2) | 11.9 (4.4) | 12.4 (5.1) | 11.1 (5.0) |

| (n)3 | (717) | (203) | (196) | (112) | (84) |

The sample was restricted to adolescents with the outcomes defined in the column headings.

The sample was restricted to adolescents that had a lifetime plan.

Denominator n for each column.

We next examined whether lifetime treatment was first received before the year the adolescent first experienced each suicidal behavior, the same year, or only after their suicidal behavior. These analyses reveal that most suicidal adolescents (55.3–73.2% across outcomes) receive some form of treatment before the onset of their suicidal behavior—most often mental health or school-based services. The prevalence of first receiving treatment is substantially lower during the same year as the onset of their suicidal behavior (10.8–18.2%) and in the years following first suicidal behavior (8.1–12.4%).

COMMENT

This study presented nationally-representative data on the lifetime prevalence, correlates, and treatment of adolescent suicidal behaviors. We estimate that 12.1% of US adolescents experience suicide ideation, 4.0% develop a suicide plan, and 4.1% make a suicide attempt. These estimates are consistent with those reported in prior studies using smaller samples.1–3 Nationally representative studies of adults have reported that first onset of suicidal behaviors increases dramatically during adolescence.35 The current study provides a more fine-grained picture of these increases and extends prior studies in documenting that approximately one-third of youth with suicide ideation go on to develop a suicide plan during adolescence, approximately 60% of those with a plan make a suicide attempt, and most who make this transition do so within the first year after onset. This information is important not only for a scientific understanding of suicidal behaviors, but for clinicians monitoring risk among suicidal adolescents and for public health efforts to identify those at risk for suicide attempts. These findings also inform the debate about the use of suicide ideation as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials36 and argue strongly for close monitoring of adolescents with a suicide plan, especially during the first year of onset.

The elevated odds of suicidal behavior among girls and the lower odds among Non-Hispanic Blacks are consistent with prior studies.1, 3, 7, 37 It is well-documented that although females have higher rates of nonlethal suicidal behaviors, males have higher rates of suicide death – a difference due in part to the more lethal methods used by males in their suicide attempts (e.g., firearms). We also observed elevated odds of suicidal behavior among adolescents whose parents had intermediate levels of education and lower odds of suicidal behavior among those living with biological parents and having more siblings. These latter two findings, also consistent with previous reports,11, 38, 39 might reflect influences of social support that buffer against stress or psychopathology or might be markers of low exposure to adversity and/or low genetic risk.

This study also provides new information about the associations of temporally primary mental disorders with subsequent adolescent suicidal behaviors.1, 5, 6, 8, 9 The rates of prior mental disorders among suicidal adolescents found here are somewhat higher than in previous community studies of adolescents1–3 and adults,40 possibly reflecting the fact that the NCS-A examined more disorders than previous studies. Although virtually all mental disorders examined predicted a suicide attempt in bivariate models, these associations were largely explained by mental disorders predicting suicide ideation. Among those with ideation, only MDD/dysthymia predicted the development of a suicide plan and only a handful of disorders predicted the transition from ideation to a suicide attempt (i.e., MDD/dysthymia, eating disorders, ADHD, conduct disorder [only for unplanned attempt] and IED [only for planned attempt]). These findings are consistent with recent findings in epidemiological studies of adults, in which MDD emerged as the strongest predictor of suicidal thoughts compared to disorders characterized by anxiety, agitation, and poor behavioral control being the strongest predictors of suicide attempt among ideators.22, 40

Several of the findings raise questions that require further study and theorizing. Our finding that IED predicts only planned, not unplanned, suicide attempts is surprising given the impulsive nature of IED. Notably, though, we observed this same pattern in two prior studies,22, 40 suggesting that it is not merely a chance finding in the current study. Future research is needed to study this association in more depth in the context of a broader investigation of the roles of impulsiveness and planning in suicidal behaviors. Another interesting finding was that SAD was associated with consistently low odds of all subsequent suicidal behaviors and significantly so for planned suicide attempts. Although speculative, it may be that adolescents who fear leaving their parents are less likely to act on suicidal thoughts and plans for fear of losing them. Prior studies have found that anxiety disorders protect against oppositional/aggressive behavior.41 A similar process might exist for suicidal behavior. Nevertheless, given the large number of coefficients examined, the significant association of SAD with reduced odds of an attempt among planners should be considered no more than provisional until replicated in independent samples.

Several aspects of the results regarding treatment are especially noteworthy. The fact that most suicidal adolescents who receive treatment see a mental health specialist suggests that such adolescents are getting access to those most qualified to treat them. In addition, the fact that the proportion in treatment increases with severity (i.e., ideation<plan<attempt) implies that the treatment system is responsive to variation in severity. However, it is noteworthy that suicidal adolescents typically enter treatment before rather than after onset of suicidal behaviors. This means that mental health professionals are not simply meeting with adolescents in response to their suicidal thoughts or behaviors, but that adolescents who are clinically severe enough to become suicidal more typically enter treatment before onset of suicidal behaviors. There is no way to know from the NCS-A data how often this early intervention prevents the occurrence of suicidal behaviors that would otherwise have occurred but were not observed in our data. It is clear, though, that treatment does not always succeed in this way, as the adolescent suicide attempters in the NCS-A that received treatment prior to their first attempt went on to make an attempt. This finding is consistent with recent data highlighting the difficulty of reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adolescents.42 We are unaware of any prior epidemiologic data on the lifetime treatment of suicidal adolescents, so there is no basis for comparison of our findings with those of previous studies. However, a recent report found that 12-month treatment of adults with suicidal behavior in 21 countries averaged 40%43 and was higher in the US (63–82%).43, 44 The slightly higher rate of treatment observed in the current study than in these adult studies reflects the fact that we examined lifetime rather than 12-month treatment and that prevalence of mental disorders among those with suicidal behaviors, which is associated with increased probability of treatment,45 was higher in the NCS-A than in the other studies.

The above findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, results are based on retrospective self-reports that may be subject to recall bias. Second, mental disorders were assessed with a fully-structured instrument rather than clinical assessment, although this limitation is tempered somewhat by the good concordance between survey diagnoses and blinded clinical diagnoses.14 Third, several disorders known to be associated with suicidal behavior were not examined (e.g., schizophrenia, personality disorders). Fourth, some of the disorders found to be significant are likely to have been false positives due to the large number of tests carried out. It is consequently important to consider the results regarding these associations provisional until they are replicated. Fifth, we examined only a limited set of predictors. For example, we did not consider health risk behaviors, protective factors, or family-community predictors. Sixth, we focused only on onset of suicidal behaviors and did not examine either severity or persistence or inquire specifically about intent to die. Seventh, we did not validate reports of treatment. Nor did we examine adequacy of treatment. These limitations notwithstanding, the study provides valuable new information about suicidal behaviors among adolescents. The results point to the need for future work to increase our understanding of the dramatic increase in suicidal behaviors during adolescence, the causal pathways linking child-adolescent mental disorders to adolescent suicidal behaviors, and actionable strategies for clinical prediction and prevention of these behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The NCS-A is supported by grants U01-MH60220, R01-MH66627, U01MH060220-09S1, K01-MH092526 (McLaughlin), and K01-MH085710 (Green) from the National Institute of Mental Health, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044780 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust. The World Mental Health Data Coordination Centres have been supported by grants R01-MH070884, R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-MH077883 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant R01-DA016558 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant FIRCA R03-TW006481 from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the Pan American Health Organization, and unrestricted educational grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Sanofi-aventis, and Wyeth.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors had full access to all of the data in the study. Dr Kessler takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US government.

Additional Information: A complete list of NCS-A publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. A public-use version of the NCS-A data set is available for secondary analysis. Instructions for accessing the data set can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php. A detailed set of subsample prevalence tables has been posted on the NCS Web site (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/publications.php) in conjunction with the publication of this article. The NCS-A is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. A complete list of World Mental Health Survey Initiative publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

Additional Contributions: We thank the staff of the World Mental Health Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Kessler has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, HealthCore Inc, Health Dialog, Integrated Benefits Institute, John Snow Inc, Kaiser Permanente, Matria Inc, Mensante, Merck and Co Inc, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc, Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, sanofi-aventis, Shire US Inc, SRA International Inc, Takeda Global Research and Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly and Co, Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co, EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc, sanofi-aventis, and Shire US Inc. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed suicide in adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung HC. Deaths: preliminary data for 2009. Nat Vital Stat Report. 2011;59(4):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, Angold A. Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry Sep. 2006;63(9):1017–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(2):297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Baldwin CL. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):427–434. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Kramer R, Flisher AJ, Goodman S, Canino G, Shaffer D. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):339–348. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1093–1099. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, Chen T, Chiappetta L. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(12):1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(2):69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell BE, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):380–385. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, Gruber MJ, Guyer M, He Y, Jin R, Kaufman J, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Koretz D, Kessler RC. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):367–369. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819996f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, He JP, Koretz D, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Prevalence, Persistence, and Sociodemographic Correlates of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Green JG, Gruber MJ, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Severity of 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders in the NCS-R Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Arch Gen Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1603. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husky MM, Olfson M, He JP, Nock MK, Swanson SA, Merikangas KR. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and service use in adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. 2012. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Borges G, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Huang Y, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Kovess V, Levinson D, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tomov T, Viana MC, Williams DR. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Pine DS, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Psychol Med. 2012:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Issues in parent-child agreement: the case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5(1):57–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1014573708569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Rao U, Ryan ND. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, Georgiades K, Heaton L, Swanson S, Olfson M. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Compton W, 3rd, Cottler L, Bean DL, Narrow WE, Weisz JR. The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(8):1032–1039. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Efron B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(402):414–425. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alonso J, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Schoenbaum M, Üstün TB, Rojas-Farreras S, Angermeyer M, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam AN, Kovess V, Levinson D, Liu Z, Medina-Mora ME, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Uda H, Kessler RC. Including information about co-morbidity in estimates of disease burden: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2011;41(4):873–886. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.SUDAAN 9.0.2. Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis [computer program] Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998 Apr 18;316(7139):1236–1238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-theoretic Approach. 2. NY: Spring-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam E, Kessler RC, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Williams D. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolgin E. The ultimate endpoint. Nature Medicine. 2012;18(2):190–193. doi: 10.1038/nm0212-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, Caldwell CH, Jackson JS. 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):271–282. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1155–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sourander A, Klomek AB, Niemela S, Haavisto A, Gyllenberg D, Helenius H, Sillanmaki L, Ristkari T, Kumpulainen K, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Piha J, Almqvist F, Gould MS. Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts: findings from the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):398–406. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(7):703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis JM, Mann JJ. Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. (e-published ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Hwang I, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Alonso J, Borges G, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Florescu S, Gureje O, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Kostyuchenko S, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Levinson D, Matschinger H, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Scott KM, Stein DJ, Tomov T, Viana MC, Nock MK. Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:64–70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock MK, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, Wang P, Wells KB, Zaslavsky AM. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]