Abstract

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) based nanorobotics has been used for building nano devices in semiconductors for almost a decade. Leveraging the unparallel precision localization capabilities of this technology, high resolution imaging and mechanical property characterization is now increasingly being performed in biological settings. AFM also offers the prospect for handling and manipulating biological materials at nanometer scale. It has unique advantages over other methods, permitting experiments in the liquid phase where physiological conditions can be maintained. Taking advantage of these properties, our group has visualized membrane and cytoskeletal structures of live cells by controlling the interaction force of the AFM tip with cellular components at the nN or sub-nN range. Cell stiffness changes were observed by statistically analyzing the Young’s modulus values of human keratinocytes before and after specific antibody treatment. Furthermore, we used the AFM cantilever as a robotic arm for mechanical pushing, pulling and cutting to perform nanoscale manipulations of cell-associated structures. AFM guided nano-dissection, or nanosurgery was enacted on the cell in order to sever intermediate filaments connecting neighboring keratinocytes via sub 100 nm resolution cuts. Finally, we have used a functionalized AFM tip to probe cell surface receptors to obtain binding force measurements. This technique formed the basis for Single Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS). In addition to enhancing our basic understanding of dynamic signaling events in cell biology, these advancements in AFM based biomedical investigations can be expected to facilitate the search for biomarkers related to disease diagnosis progress and treatment.

I. Introduction

Nanobiotechnology, the application of nanotechnology to the characterization and analysis of biological systems is a fast evolving field that represents the intersection of nanoscale physics, biology and engineering [1]. The centerpieces of this technology are the instrumentation and techniques that allow for the sensing and manipulation of nanoscale structures and molecules. One of the key instruments is the Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM) which measures the near-field physical interactions, mainly van der Waals forces, between the scanning probe and the materials underneath [2]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM), a member of the SPM family, has taken a front seat in driving new developments of nanobiotechnology, and there is now ever-increasing emphasis on applying nanoscale forces to investigate biological events.

AFM was developed by Binning and Quate in 1986 [3], with the first commercialized AFM available in 1989. AFM remains a high resolution imaging tool mainly used for surface science research, helping researchers visualize materials, such as semiconductors, at nanometer scale [4 5] or even sub-nano meter level to resolve atomic structures. Even today, new material characterizations still rely on the high spatial resolution capability of AFM, such as the identification of single layer graphene [6 7]. However, the application of AFM in semiconductor and material sciences are being overwhelmed by new breakthroughs in AFM guided biological investigations [8–13].

The extension of AFM into nanobiotechnology relies on its unique working features that are particularly well suited for biological studies [14–16]. First, AFM can be operated in several environments, including vacuum, air and liquid, the most important of which is the liquid environment where normal physiological conditions for biological matters can be maintained. This is a key factor for AFM studies as compared with other high resolution imaging techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Second, due to the nature of its measurement properties, AFM does not require complicated sample preparation where sample contamination and damage can possibly be introduced. For example, electron microscopy requires sample fixation, dehydration and coating processes before each observation. Third, measurement using a sharp probe, as is done in AFM, is less destructive compared with many other commonly used imaging techniques.. Furthermore, AFM measurement in stable conditions delivers a relatively high signal to noise ratio (SNR), allowing high image resolution at the nano and even sub-nano meter scale. With this level of resolution the membrane structure of single cells, single proteins and DNA molecules can be visualized in unparalleled detail.

The AFM tip can be controlled to mechanically pull, push and manipulate nanoscale objects, working as a nanorobotic arm under precise computer control. Therefore, traditional concepts in robotics such as feedback, stability, and frequency response can all be integrated into these miniatured nanorobotic systems. AFM based nanorobotics has been a tremendously useful tool in nanomanufacturing, as demonstrated by its ability to perform nanolithography, nanoassembly and manipulating nano particles [17–19]. In biology, nanomanipulation using the AFM based robotics system has substantially extended the reach of AFM in various biological fields. One such application is to functionalize the AFM tip to conduct so called single-molecule manipulations. Single strand intermediate filaments have been stretched by a controlled AFM tip to measure their tensile strength [20]. Nanosurgery has been performed on cell associated molecules with a resolution of less than 100 nm [21]. Individual DNA and protein molecules have been manipulated. The term single molecular force spectroscopy (SMFS) has been applied when using the technology to probe forces at the molecular level on surface membranes [22 23].

The cellular response to varying physiological conditions is often manifested as alterations in cellular mechanics. A recent AFM study [24] has shown that during apoptosis cytoskeleton elements such as actin filaments will form a thick layer wrapping around the collapsed nucleus, thus resulting in a time lapse stiffness change; first a decrease and then an increase. Dynamic mechanical properties such as elasticity and viscoelasticity can be revealed by AFM and may serve as biomarkers, or even regulators of signaling events and physiological processes. Furthermore, AFM allows these changes in biological structures to be visualized through high resolution images. Thus, AFM based nanorobotic operations are proving to be an exciting and novel technology that may be uniquely suited for the capture of biologically relevant information linking mechanostructural and functional events.

II. Application of AFM in bionanoscience

2.1 AFM high resolution imaging for structural characterization

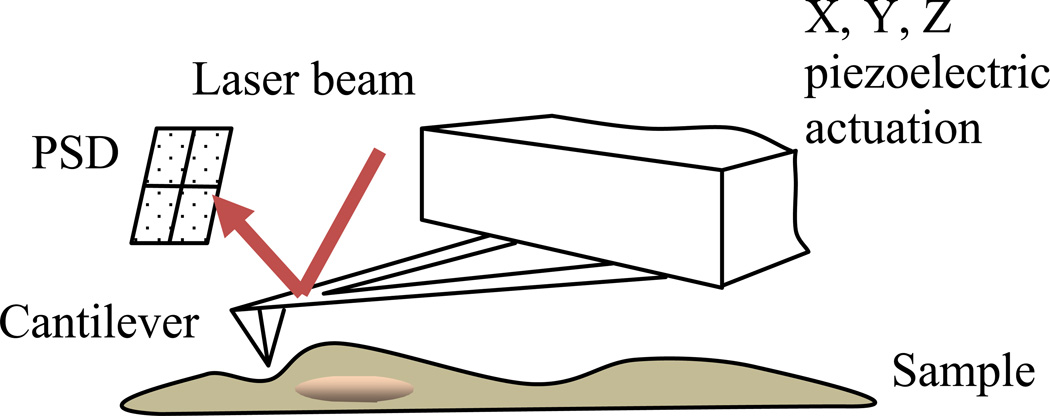

The imaging principle of AFM is relatively simple. A cantilever with a sharp tip is operated to scan across the sample surface to probe its topography. The main functioning unit is the piezoelectric actuator which drives the cantilever both horizontally, the XY scanning direction, and vertically, the Z motion direction. During the XY scanning, the interaction force (mostly van der Waals forces and sometimes electrostatic forces) between the scanning AFM tip and the sample surface will cause the bending of the cantilever. A laser beam which is reflected from the back of the cantilever is able to record this bending with a position sensitive device (PSD). The Z piezo will move accordingly to keep the tip at a constant oscillation (tapping mode) or in contact with the sample (contact mode). A schematic of the working principle of AFM is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A schematic drawing of the AFM imaging principle.

By this simple mechanism, complex biological structures can be visualized with nanoscale detail. When imaged in liquid, biological samples are often rendered soft and delicate. Therefore, the contact force must be well controlled to avoid damage to the sample surface. Typically for contact mode AFM imaging, the applied force should be adjusted to less than 100 pN for live cell imaging (this value varies for different cell types). At this interaction force, the deformation of the cell membrane can be recovered [25]; any force larger than this value would pose potential irreversible damage to the cell membrane and cytoskeleton. However, the applied force can also be used to highlight the stiffer structures underneath the soft cell membrane. In this case, the AFM tip will press against the soft cell membrane into the cytoplasm until the membrane is supported by the underlying filaments structures, allowing the underlying structures to be highlighted in both the topography and deflection images. The most important aspect for this imaging mode is to accurately control the applied force.

Not only is the normal force applied by contact mode a potential damaging factor for biological samples, but the lateral or frictional force that “scratches” the surface must also be considered. The development of tapping mode AFM imaging has proved a good solution to this problem [26]. By oscillating the cantilever at its resonance frequency in liquid with a pre-defined amplitude, the sharp tip at the end of the cantilever is free of contact with the sample. The interaction force between the sample and the tip reduces the oscillation amplitude and also induces a phase shift. By controlling the vertical piezo to maintain the desired amplitude, topography information can be obtained. In fact, the phase shift provides indirect, quasi-quantitative data for mechanical property analysis.

The ever-developing techniques for AFM imaging of biological samples have led to a number of breakthroughs in the biological sciences. The surface structure of bacteria cells was visualized with lateral resolution around 2 nm with an applied force around 80 pN [27]. Membrane protein structures have been revealed with tetramer configurations at sub-angstrom resolution in the vertical direction. Animal cells have been imaged live to obtain structural information on cell membranes or underlying cytoskeleton structures [28]. At an even larger scale, cartilage tissues were imaged to determine their fibril composite [29]. These experiments truly demonstrate the spatial resolving capability of AFM for biological materials under physiological conditions; in some cases this has been used to confirm crystallography data for defined structural conformations.

Keratinocytes are epithelial skin cells characterized by their strong intercellular adhesion through bundles of intermediate filaments within so-called desmosomes. Desmosomal adhesion structures support the mechanical integrity and maintain the strength of cutaneous tissue. Intercellular junctions can be destroyed by self tissue-directed antibodies to specific proteins in auto-immune conditions such as Pemphigus vulgaris (PV). Using tapping mode AFM imaging on both fixed and live cells in fluid, our group has visualized the disruption of cellular junctions following antibody binding [10]. Detailed analysis of AFM deflection images revealed significant surface change in response to antibody interaction in real time. The live cell images in Fig. 2 show the topography and the surface detail of keratinocytes in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The cytoskeleton beneath the cell membrane was highlighted by the applied force, revealing actin filaments at the center of the cell and intermediate filaments at the peripheral connecting neighboring cells.

Fig. 2.

High resolution images showing the cytoskeleton structure under the applied peak force of 5 nN, scan size: 30 µm.

2.2 AFM in combination with other imaging modalities

2.2.1 AFM combined with fluorescence microscopy

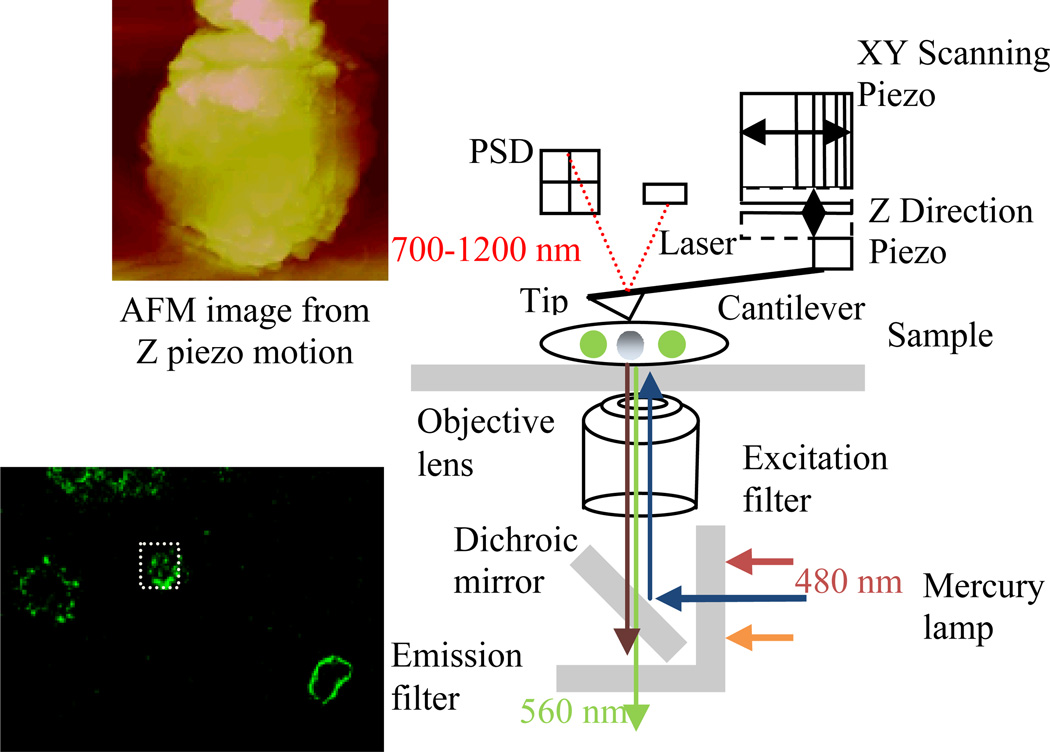

Several studies have utilized a combination of AFM with optical microscopy techniques to localize desired targets (schematically shown in Fig. 3). For the majority of these studies, AFM is used to image the topography of a sample while a fluorescence image is collected simultaneously. The fluorescence image is used to guide the AFM tip to certain locations where a specific agent is labeled, allowing detailed structural images to be obtained around the labeled molecule. In other cases, the AFM tip is employed as a mechanical device to manipulate the sample while at the same time conducting fluorescence imaging. A few papers have examined the mechanical properties of single molecules by using AFM to stretch them and simultaneously visualize the stretching process by fluorescence imaging [30]. However, a concern with this combination of techniques is the interference between the excitation light and the emission light from the fluorescence microscopy and the laser for AFM deflection recording. The laser used for cantilever deflection detection has a wavelength in near infrared (NIR) ranging from 700 to 1200 nm [31], while in most cases fluorescence excitation and emission wavelength is less than 700 nm, in the visible light range space; for FITC the excitation and emission wavelengths are 480 and 560 nm, respectively shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The combination configuration of fluorescence microscopy with AFM. Simultaneous imaging of B lymphoma cells labeled with anti-CD20 (FITC labeled) surface receptor and the AFM is shown.

Our group undertook AFM characterization of keratinocyte intercellular junctions in combination with the labeling of the desmosomal protein desmoplakin in red and cytoskeletal element intermediate filaments in green. The fluorescence imaging was used to direct the localization of the AFM scanning tip to the desired cell junctional areas where there was a concentration of desmoplakin (red). Fig. 4 shows the correlation of fluorescence image and AFM images of keratinocytes within intact desmosomes. Thus, AFM and fluorescence imaging work in a complementary fashion in this characterization process.

Fig.4.

Fluorescence (A) and AFM imaging (B, C) combined to characterize cells with intact desmosomes. Scan sized are 100 µm (B) and 50 µm (C), respectively, from top to bottom.

2.2.2 AFM in combination with SEM

If we consider the combination of fluorescence imaging with AFM to be more of an instrumental combination, then AFM combined with SEM could be considered as a functional combination. A few investigators have used SEM to confirm structures observed in AFM. SEM has much larger scanning area, and thereby can be used to complement the AFM measurement. In one study, SEM was operated in low acceleration voltage to observe vesicle structures on the cell membranes [32]. Vesicle pits normally contain a substantial amount of water. Thus, when imaged by AFM under low loading force, the pit structure may not be elevated. Only when a certain contact force is applied on the surface can the pit be visualized with higher contrast between the water-filled area and the unfilled area. However, this pit structure can be directly observed under SEM. Before SEM imaging, samples need to be dehydrated. Therefore, the water containing vesicles will be highlighted after shrinkage due to the drying process. The inhomogeneity of the membrane surface can then be confirmed.

Our group characterized keratinocyte intercellular junctional structures by the functional combination of AFM and SEM as shown in Fig. 5. SEM and AFM provide images in different sizes and resolution that confirm and validate each other.

Fig. 5.

AFM (bottom) combined with SEM (up) for intercellular junction characterization. Scale bars: 20 µm and 2 µm respectively.

2.2.3 AFM in combination with Raman spectroscopy

The combination of AFM with Raman spectroscopy was introduced approximately ten years ago termed as tip enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) [33]. This method takes advantage of the high spatial resolution of scanning probe microscopy to obtain topography images while performing surface chemical sensing at the nanoscale. The AFM tip is coated with metal (normally silver) to further enhance the Raman signal. When the laser is irradiated onto the metal surface of the AFM tip closely engaged with the sample surface, field- enhancement occurs to excite molecules around the tip that allows Raman spectroscopy with a higher lateral resolution as compared with surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). The most common application of TERS in bio-imaging is to chemically characterize biomaterials [34]. Further development and refinement of this method is required before it can be routinely applied to more complex biological samples and processes.

2.3 AFM nanoindentation for mechanical property characterization

2.3.1 Elasticity measurement on keratinocytes

Mechanical properties of structures can be characterized by recording force displacement curves via AFM nano indentation. Following Hertzian model analysis of force curves, a quantitative Young’s modulus can be generated. For this purpose, the AFM tip is driven by piezoelectric actuator along its Z direction towards the sample and then retracted back over a pre-defined distance. The movement of the piezoelectric actuator is then used to drive the AFM cantilever vertically and the deflection signal from the cantilever is recorded as a force-displacement curve.

The force curve plots the relation between the cantilever displacement (z) and its vertical deflection (d). A hard sample surface is regarded as indefinitely stiff compared with the cantilever and thus will not be indented at all. Therefore, the force curve has a slope of one, meaning the deflection equals the cantilever displacement. The deflection sensitivity which correlates the photodiode voltage with the deflection of the cantilever can be calibrated by this hard surface force curve. Moreover, it is a natural reference for soft surface force curves. The soft surface on which indentation becomes dominant will have a slope less than one. The difference between the two in the deflection axis is the indentation depth. δ

| (1) |

The point from where the force curve slope starts is called the contact point, where the initial contact between the tip and the sample surface was established. Thus, the offset of both the displacement (z0) and the deflection (d0) before the contact point should be subtracted, as shown in Fig. 6A.

| (2) |

Fig. 6.

The conversion of force-displacement curve to force-indentation curve (A); The fitting of the force indentation curve by Hertz model to generate the Young’s modulus (B).

The indentation force can be easily calculated by applying Hooke’s law to the cantilever, where k is the spring constant of the cantilever.

| (3) |

Therefore, the force displacement is converted to the force indentation curve which directly depicts the stiffness of the cell surface (Fig. 6A). The force indentation curve can be further fitted to the Hertzian model to generate the quantitative data on the Young’s modulus (E) of the cell surface (Fig. 6B). For a conical tip the relationship between the applied force and the indentation can be expressed as [35]:

| (4) |

where α is the half opening angle of a conical shaped indenter and ν is the Poisson ratio.

A number of studies have used a spherical tip at the end of the cantilever instead of a conical shape for indentation measurement. The fabrication process involves gluing a spherical particle, normally polymeric and with 1 µm to 5 µm diameter, to one end of the cantilever. In this case, the relationship between the indentation and the applied load will be slightly different from equation (4).

| (5) |

Where R is the radius of the sphere and the other quantities remain.

The main advantage of using a spherical AFM tip for nanoindentation is less damage to a soft sample compared with the sharp conical tip, normally 10 to 40 nm in diameter at the apex. The spherical tip can induce deformation of a large area; therefore, the global stiffness can be measured [36]. On the other hand, a sharp tip indents a much smaller area, and it resolves local stiffness very well. This is especially useful when the inhomogeneity of the biological samples matters most. With cells, for example, the underlying cytoskeleton that supports the soft membrane is not evenly distributed and organized. In this case, the dynamic distribution and organization of the cytoskeleton may be best monitored by measuring the local stiffness using the conical tip.

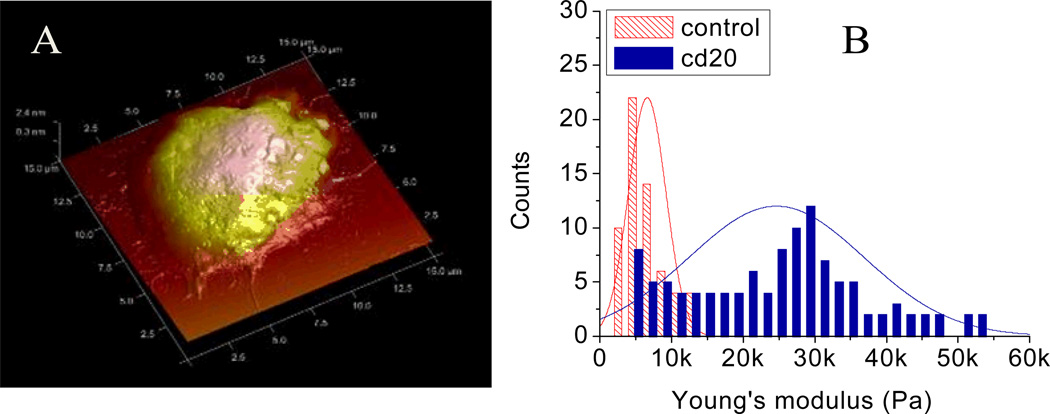

To identify the mechanical property of a cell population which is not homogenous, statistical analysis of a large number of cells must be undertaken. Transformed B cells are the cancerous cell type normally found in Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL). One of the treatments for NHL is Rituximab, an antibody targeting CD20, a surface receptor expressed on normal B cells and B lymphoma cells. This treatment eventually leads to lymphoma cell apoptosis. An AFM image in Fig. 7A shows the fixed 3D structure of a B lymphoma cell which has diameter around 10 µm. Shown in Fig.7B is the quantitative measurement of 180 B lymphoma cells (60 control samples and 120 anti-CD20 antibody treated samples). Normal B lymphoma cells have a Gaussian-distributed Young’s modulus with a mean around 5 kPa, while the cell samples after Rituximab treatment shows a normal distribution of Young’s modulus values with a mean around 25 kPa (but with values that are distributed more widely than normal B cells) that is indicative of cellular apoptosis. The change of this mechanical property could be obtained only by evaluation of a large number of samples [12].

Fig.7.

(A) Three dimensional AFM image of a B lymphoma cell; (B) Young’s modulus distribution for control sample and anti-CD20 treated samples of B lymphoma cells, scan size: 15 µm.

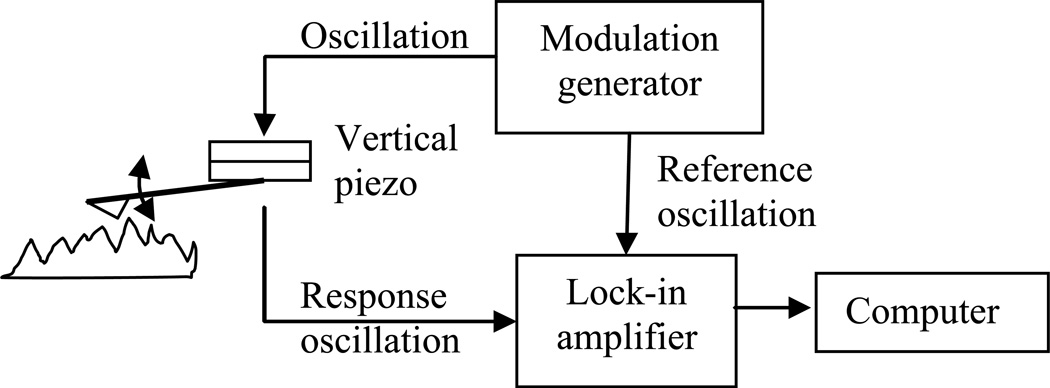

2.3.2 Viscoelasticity by AFM based force modulation

Force modulation imaging is an AFM technique that maps differences in surface stiffness [37]. It is based on contact mode AFM imaging. The basic principle for force modulation is to add a small vertical oscillation of the tip during the contact scanning. That means the contact force is modulated while the average is still the same as in contact mode. When the tip is modulated with a vertical displacement around 10 nm with a frequency ranging from 0.5 Hz to 500 Hz [38], there will be a difference in the resistance of this oscillation among areas with different mechanical properties. This resistance can be measured as the viscoelasticity of the sample. The schematic drawing of the modulation process is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of force modulation by AFM.

For a spherical shaped AFM tip, the applied normal force, a complex with different modulation frequency can be denoted as (derived from equation (5)) [39]:

| (6) |

Where ν is the Poisson ratio, R is the radius of the probe and E0 is the elastic modulus at zero frequency. is the frequency-dependent elastic modulus. is the indentation displacement caused by the oscillation force, and δ0 is the main indentation caused by the applied force by contact AFM.

Two components constitute the applied force: the contact force and the oscillation force. The original Hertz model force is the same as equation (5). And the oscillation force is:

| (7) |

The complex modulus can therefore be expressed as the relation between the applied complex force and the indentation as well as the indentation displacement:

| (8) |

From equation (8), we can calculate the elastic moduli of the viscoelastic biological samples with the real part G′ as the storage modulus and the imaginary part G″ as loss modulus.

III. AFM extended applications with nanobiomanipulation

3.1 Development and application of AFM-based nanobiomanipulation

The imaging of AFM is the direct result of the scanning motion driven by the XY direction piezo actuation unit. From the control point of view, the zigzag shaped driving voltage is applied to the XY piezo scanner, causing a linear motion back and forth with a pre-defined frequency. However, this is not the case for a nanomanipulation operation, where the position of the tip is not linearly related and the applied voltage should be an arbitrary shape rather than a zigzag [40]. Besides, most nanomanipulation operations on biological samples are performed in liquid. Thus, the viscoelasticity of the sample requires a higher response frequency, and the control system should be upgraded to meet this demand. The schematic drawing in Fig. 9 shows the upgraded hardware and software configurations from a commercial AFM to a nanobiomanipulation oriented AFM. The signal access module provides all the signals needed for the external control of the manipulation operation by the Linux controller with DAQ cards as the interface. The joystick is the command input where all the motions start, enabling the precision manipulation of nanoscale objects. The force feedback from the joystick makes it an ideal augmented reality environment.

Fig. 9.

AFM nanomanipulation system with joystick control architecture

By utilizing the AFM tip as a robotic arm the capability of AFM can be extended greatly. AFM based nanomanipulation has had great success in nanomanufacturing, including nanolithography and nanoassembly. More recently, biological applications have been conducted, including using a functionalized tip for chemical force sensing as in Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) and for surface receptor mapping [41].

3.1.1 DNA manipulation

DNA molecules are mechanically flexible and physicochemically stable. The capability of AFM to maneuver objects at the molecular level has allowed the manipulation of DNA. Based on the behavior model of DNA, the operation can be displayed in real time in an augmented reality environment. An example of DNA manipulation is shown in Fig.10. Fig. 10A shows DNA molecules in their original configuration; Fig 10B shows the manipulation of DNA molecules displayed in the manipulation interface; Fig. 10C shows an AFM image after manipulation. It can be seen that several kinks have been created by slightly “pushing” individual DNA strands or bundles. The kinks created in the interface (image in Fig. 10 B) are very similar to the actual AFM image post manipulation (Fig. 10 C) [8].

Fig. 10.

Pushing DNA on a polycarbonate surface (scanning range of 5um). (A) Image of DNA before pushing. (B) The real time display in the augmented reality during pushing. The kinks inside the circles are created by elaborately pushing. (C) A new scanning image after several pushing operations. (Adapted from [8])

3.1.2 Single cell manipulation

There are a number of different mechanisms for single cell manipulation, including micropipette aspiration, optical trapping, magnetic twisting, and nanoindentation, etc. Each technique works differently to fit different mechanical models for single cell structures. Regarding AFM based single cell manipulation, the main operation is AFM based nanoindentation. There are two different types of AFM based nanomanipulation: unpenetrated nanoindentation and penetrated nanoindentation.

For unpenetrated nanoindentation, the sharp AFM tip only deforms the membrane surface of the cell. Because the cell membrane is supported by and propagated through the cytoskeleton, deformation at the surface can result in cytoskeletal re-configuration. Altered cytoskeleton organization results in an altered response to the applied load, and is eventually manifested in the form of changes in the overall stiffness of the cell body. There is also work to suggest that the tension in the cell membrane is mainly responsible for the stiffness behavior of the cell body, like a balloon filled with liquid [42]. However, recent findings indicate that the cell may behave more like a globally interconnected structure covered by a soft membrane, like a tent that is nailed to the ground [43]. This is also consistent with AFM imaging data where high applied contact force elevates the intracellular actin network.

For penetrated nanoindentation, the sharp AFM tip is used as a nanoneedle to penetrate the membrane and reach the actin filament network underneath. The applied force just before the penetration can be correlated with the indentation depth just before penetration. One important potential application of penetrated nanoindentation is for controlled drug delivery [44]. The nanoneedle can be fabricated with a hollow inner structure whereby certain drugs can be pumped into the cell upon penetration in a controlled fashion.

3.1.3 Filament manipulation and characterization

The cytoskeletal structure supports the cell, performs functions such as vesicle transportation and protein anchoring, and regulates the cell shape and movement. It composed of three different filament structures: actin filaments, intermediate filaments and microtubules. Each group of proteins is critical for cellular functioning. Dynein is a basic protein that is assembled together to make microtubules. It functions as a motor protein that converts chemical energy conserved in ATP to mechanical energy required for movement [45]. This process may provide a powerhouse for the development of future self-assembly fabrication processes to construct complex devices from nano building blocks.

Recently, mechanical properties of intermediate filaments have been studied using AFM based nanomanipulation systems [46]. For one study, intermediate filaments absorbed on the mica surface were stretched by AFM tip. The manipulation operation itself in this case was routine, but the findings from the experiment were striking. Intermediate filaments could be stretched more than two fold of original length. This in vitro experiment also confirmed the role of intermediate filament in the maintenance of mechanical integrity of the cell body and in providing strength for the entire tissue. These roles are performed particularly well when cells are undergoing a large extent of deformation, and can be systematically studied by this AFM nanomanipulation technique.

3.1.4 Nanodissection and Nanosurgery

A very special group of operations using AFM involves nanodissection, or nanosurgery. The main purpose of this operation is to isolate, or partially isolate a group of cellular and/or moleculer structures from other structures. There is literature on the dissection of DNA molecules, proteins, cell membranes, intermediate filaments, among other structures. Most of these experiments were performed for the sole purpose of demonstrating the capability of AFM based nanobiomanipulation systems in handling and changing biological matters. Our group has extended the application of nanosurgery to demonstrate that it can be a novel tool to re-create and disrupt specific functional biological activities with unparalleled precision (discussed below).

3.2 AFM-based nanosurgery on keratinocytes

Keratinocytes normally have diameters around 15 µm, while the intercellular junction area composed of intermediate filaments and cell membrane materials can be less than 100 nm. By dissecting adhesion junctions between cells, our group attempted to mimic the damaging effect caused by pathogenic auto-antibody binding and to study the resulting cytoskeleton rearrangement (Fig. 11).

Fig.11.

Schematic drawing of the nanobiomanipulation tasks of dissecting the intercellular junctions of keratinocytes. The motion path of the nanodissection is denoted around the periphery of the cell perpendicular to intermediate filaments

The topography image shows three keratinocytes connected by intercellular junction molecules, mainly intermediate filaments. A few intermediate filament bundles were cut off as indicated by the circles. During the cutting process the AFM tip travelled a distance of approximately 8 µm. The AFM images before and after the dissection clearly illustrate the topographical difference subsequent to dissection (Fig. 12).

Fig.12.

The keratinocytes before and after nanodissection imaged by AFM. The arrow in both AFM images shows the disappearance of a bundle of intermediate filaments, scan size: 24.6 µm.

We have previously found that the treatment of keratinocytes with pathogenic antibody decreases cellular stiffness. We speculated that this decrease in stiffness is linked to the loss of intercellular adhesion structures, as imaged by fluorescence microcopy combined with AFM. Thus, the damaged desmosome loses its “spot-welding” function and can no longer hold together intermediate filaments from neighboring cells. We hypothesized that cells without the full compliment of intermediate filaments linking to adjacent cells would undergo a period of adjustment to reach a state with lower prestress. Less prestress in the cytoskeleton would result in less stiffness in the cell body. This is in alignment with the tensegrity model developed by Ingber [43]. Using nanodissection, we achieved the same effect as antibody binding disruption of the intermediate filament bundle connections.

3.3 AFM functionalized tip for surface receptor recognition

3.3.1 Tip functionalization based on self-assembly

Functionalization of AFM tips by coating them with antibodies or ligands has extended the application of AFM for studying specific interactions at a molecular level, e.g. binding force for molecular interaction or molecular recognition. The functionalization process is mainly based on the self-assembly ability of chemical agents at molecular level. There are three ways to functionalize the AFM probes with functional agents: (i) The simplest method is by direct coating of a functional protein to the AFM tip. While this is not technically difficult, the binding strength here may not be strong enough. A common strategy to improve the binding is to employ certain crosslinking reagents to link the functional agents onto the AFM probe. (ii) The intermediate linking method is a much more complicated procedure, but it results in a larger binding force between the AFM tip and the functional agents. It also provides a higher degree of spatial specificity. This functionalization method usually employs a linker to covalently bind the proteins in order to expose specific site(s) within selected molecules. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a common crosslinking reagent. A terminal thiol group can be first attached to the antibody or protein and this thiol group will be able to covalently bind to PEG [47]. The AFM tip should be cleaned and processed to add an amine group layer, which can then be cross-linked to PEG. This functionalization process is schematically shown in Fig. 13, using Rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) functionalization as an example. (iii) One of the most common ways to functionalize the AFM tip is by the formation of Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) [47]. The formation of SAM is achieved by thiol chemistry, similar to the coating of polymer PEG. After the initial binding of thiol with gold, the large space between molecules enables the thiolyated alkyls to be horizontally oriented. As the density of the horizontally aligned alkyls increases, the lateral interaction through van der Waals forces drives the alkyls to lift off and finally align upright as depicted in Fig. 14.

Fig. 13.

Tip functionalization with the intermediate linker molecules.

Fig. 14.

SAM formation onto goad coated AFM tip.

3.3.2 AFM CD20 receptor recognition on B cell lymphoma cells

Biological coating has been mostly used for measuring the binding force between a receptor and a ligand, including antigen-antibody-pairs, as well as mapping the distribution of binding partners on samples. For the B lymphoma example mentioned above, there is a strong affinity-binding activity between the CD20 receptor on the B cell surface and the Rituximab anti-CD20 antibody. Therefore, by linking the Rituximab antibody onto the AFM cantilever by processes mentioned above, we were able to recognize the surface receptors and also measure the binding force between the two. The tip functionalization process is shown in Fig.13 using a PEG based linker.

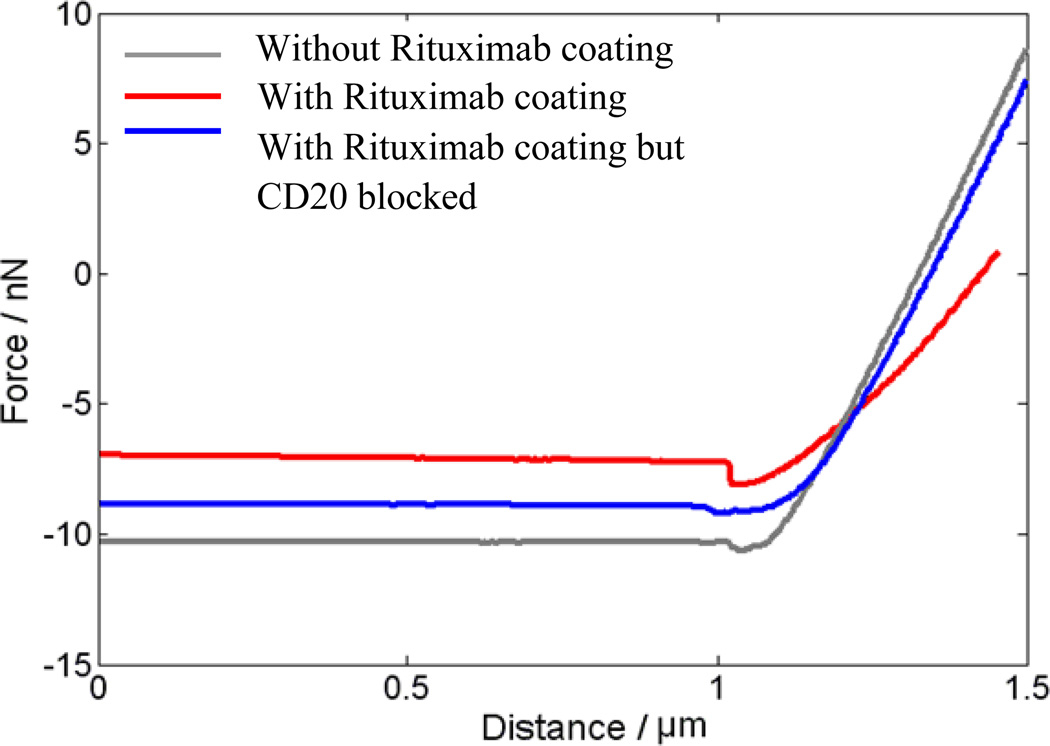

The AFM tip was first brought into contact with the cell sample (Process A in the Fig. 15). When there is affinity binding activity between the Rituximab coated AFM tip and the surface receptor CD20, the adhesive forces dominate the interaction between the AFM tip and the sample below (B). When the cantilever is pulled back from the sample, the adhesive interaction drag back the cantilever and this is detected by the high sensitivity cantilever bending (C). The bending of the cantilever through the whole process A to D is recorded as a function of the vertical displacement of the piezo drive. From the force distance curve, this dragging effect can be calculated as the force difference between the baseline and the minimum. Normally, drag effect always exists when the AFM cantilever pulls back from the sample due to the van der Waals force, but the force is quite small. The experimental data with three different conditions for the Rituximab based surface receptor CD20 binding force is shown in Fig. 16. The force curve with Rituximab functionalized AFM tip has a much larger dragging force compared with two controls - one normal AFM tip without functionalization, and the other one where the tip was functionalized but the surface receptor CD20 was blocked before the measurement. The force calculated from the force displacement curve is around 1 to 2 nN. However, this binding force shows the cluster of CD20-Rituximab binding activity. To obtain the binding force for single bonds, more detailed analyses would need to be performed.

Fig. 15.

The binding force measuring process.

Fig. 16.

The force measurement taken with Rituximab, without Rituximab and a neutralized surface;

IV. Remaining challenges and future directions

AFM applications are providing increasing insights onto biological processes that are otherwise not offered by other techniques. With its unique operating environment, AFM high resolution structural imaging and nanomechanical measurement provide real-time structural and functional information during the course of biological events. AFM imaging can be combined with other imaging modalities such as florescence imaging and electron microscopy to boost its capability. Furthermore, with the introduction of robotic concepts nanobiomanipulation can be performed on single cells, DNA molecules and membrane proteins. However, there are still technological challenges that need to be solved for even more precise monitoring of biological phenomenon.

Biological events are normally time sensitive. Most of these processes occur much faster than the time it takes to capture a full frame AFM image. Therefore, a continuing goal is to improve temporal resolution while maintaining spatial resolution. The use of high-speed AFM to track macromolecules may be useful for this purpose [48]. Future exploration may include developing AFM imaging modalities correlated with a series of newer techniques to capture more precise biomarkers for various biological processes. For instance, AFM combined with Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCMD) enables measurement of physical changes (energy dissipation) while observing structural changes [49 50].

AFM based nanobiomanipulation requires in situ sensing while the manipulation operation is being performed. Thus, the AFM process needs to be able to switch between imaging mode and manipulation mode periodically with high frequency during manipulation. In manipulation mode the AFM tracks the operator input, while in imaging mode it performs in a zigzag motion allowing the effect of the operations to be visualized simultaneously. Dual probe systems have also been proposed in which one cantilever performs the manipulation while a second cantilever senses the manipulation. This technique may be particularly useful for experiments involving local drug delivery or site-specific nanosurgery [51]. Multiple probe sensing arrays have also been envisioned to enhance the capacity of AFM readouts [52]. These exciting new developments in AFM suggest that we are on the cusp of revolutionary technologies that will no doubt open unforeseen windows into the mechanism of cellular and molecular process that underlie normal physiological as well as disease states.

Contributor Information

Ruiguo Yang, College of Engineering, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA..

Ning Xi, Email: xin@egr.msu.edu, College of Engineering, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA (Tel.: 517-432-1925; fax: 517-353-1980).

Carmen Kar Man Fung, College of Engineering, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA..

Kristina Seiffert-Sinha, Division of Dermatology and Cutaneous Sciences, Center for Investigative Dermatology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA..

King Wai Chiu Lai, College of Engineering, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA..

Animesh A. Sinha, Email: asinha@msu.edu, Division of Dermatology and Cutaneous Sciences, Center for Investigative Dermatology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA (Tel.: 517-353-7727; fax: 517-353-7730)..

Reference

- 1.Muller D, Dufrene Y. Atomic force microscopy as a multifunctional molecular toolbox in nanobiotechnology. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:261–269. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horber J, Miles M. Scanning probe evolution in biology. Science. 2003;302:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1067410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binnig G, Quate CF. Atomic Force Microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986;56:930–933. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ukraintsev VA, Baum C, Zhang G, Hall CL. The role of AFM in semiconductor technology development: the 65 nm technology node and beyond. Proc. SPIE. 2005;5752:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krauss TD, Brus LE. Charge, polarizability and photoionization of single semiconductor nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;83:4840–4843. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nature Materials. 2007;6:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai KWC, Fung CKM, Chen H, Yang R, Song B, Xi N. Manipulation and assembly methods for graphene based nano devices. IEEE Int. Conf. on Nanotechnology; Seoul, Korea. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Xi N, Wang DH. In situ sensing and manipulation of molecules in biological samples using a nanorobotic system. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2004;31:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li G, Xi N, Wang DH. Probing membrane proteins using atomic force microscopy. J. of Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;97:1191–1197. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung CKM, et al. Investigation of human keratinocytes cell adhesion using atomic force microscopy. Nanomedicine, Nanotechnology Biology, and Medicine. 2010;6:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang R, Xi N, Fung CKM, Lai KWC, Seiffer-Sinha K, Sinha AA. Analysis of keratinocytes stiffness after desmosome disruption using atomic force microscopy. IEEE Int. Conf. on Nanotechnology; Genoa, Italy. 2009. pp. 640–643. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R, Xi N, Fung CKM, Lai KWC, Seiffert-Sinha K, Sinha AA, Zhang W. Investigations of bio makers for human lymphoblastoid cells using atomic force microscopy. IEEE. Int. Conf. on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems; Xiamen, China. 2010. pp. 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung CKM, Yang R, Lai KWC, Xi N, Seiffert-Sinha K, Sinha AA. Micro fixture enabled in-situ imaging and manipulation of cell membrane protein. IEEE. Int. Conf. on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems; Xiamen, China. 2010. pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller DJ. AFM: a nanotool in membrane biology. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7986–7998. doi: 10.1021/bi800753x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li G, Xi N, Liu L, Zhang J, Lai KWC. Study of DNA properties under controlled conditions using AFM based nano-robotics. IEEE Int. Conf. on Nanotechnology; Hong Kong. 2007. pp. 1018–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel A, Muller D. Observing single biomolecules at work with the atomic force microscope. Nature Structural Biology. 2000;7:715–718. doi: 10.1038/78929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai KWC, Xi N, Fung CKM, Zhang J, Chen H, Luo Y, Wejinya UC. Automated nanomanufacturing system to assemble carbon nanotube based devices. International Journal of Robotics Research. 2009;28:523–536. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decossas S, Mazen F, Baron T, Bremond G, Souifi A. Atomic force microscopy nanomanipulation of silicon nanocrystals for nanodevice fabrication. Nanotechnology. 2003;14:1272–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xi N, Fung CKM, Yang R, Seiffert-Sinha K, Lai KWC, Sinha AA. Bionanomanipulation using atomic force microscopy. IEEE Nanotechnology Magazine. 2010;4:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann H, Bar H, Kreplak L, Strelkov S, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:562–573. doi: 10.1038/nrm2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beard JD, Burbridge DJ, Moskalenko AV, Dudko O, Yarova PL, Smirnov SV, Gordeev SN. An atomic force microscope nanoscalpel for nanolithography and biological applications. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:445302–445312. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/44/445302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rief M, Oesterhelt F, Heymann B, Gaub HE. Single molecular force spectroscopy on polysaccharides by atomic force microscopy. Science. 1997;275:1295–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuman K, Nagy A. Single molecule force spectroscopy: optical tweezers, magnatic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nature Methods. 2008;5:491–505. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelling A, Veraitch F, Chu C, Mason C, Horton M. Mechanical dynamics of single cells during early apoptosis. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2009;66:409–422. doi: 10.1002/cm.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fotiadis D, et al. Imaging and manipulation of biological structures with the AFM. Micron. 2002;33:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(01)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansma P, et al. Tapping mode atomic force microscopy in liquids. Applied Physics Letters. 1994;13:1738–1740. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheuring S, Dufrene YF. Atomic force microscopy: probing the spatial organization, interactions and elasticity of microbial cell envelopes at molecular resolution. Molecular Microbiology. 2010;75:1327–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li QS, Lee GY, Ong CN, Lim CT. AFM indentation study of breast cancer cells. BBRC. 2008;374:609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolz M, et al. Early detection of aging cartilage and osteoarthritis in mic and patient samples using atomic force microscopy. Nature Nanotechnology. 2009;4:186–192. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hards A, Zhou C, Seitz M, Brauchle C, Zumbusch A. Simultaneous AFM manipulation and fluorescence imaging of single DNA strands. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:534–540. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiara C, et al. Simultaneous mechanical stiffness and electrical potential measurements of living vascular endothelial cells using combined atomic force and epifluorescence microscopy. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:1–8. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/17/175104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riethmüller C, Schäffer T, Kienberger F, Stracke W, Oberleithner H. Vacuolar structures can be identified by AFM elasticity mapping. Ultramicroscopy. 2007;107:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flores SM, Toca-Herrera JL. The new future of scanning probe microscopy: combining atomic force microscopy with other surface-sensitive techniques, optical microscopy and fluorescence techniques. J. of Royal Society of Chemistry. 2009;1:40–49. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00156e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picardi G, Chaigneau M, Ossikovski R, Licitra C, Delapierre G. Tip enhanced Raman spectroscopy on azobenzene thiol self-assembled monolayers on Au(111) J. of Raman Spectroscopy. 2009;40:1407–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radmacher M. Measuring the elastic properties of biological samples with the AFM. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine. 1997;16:47–57. doi: 10.1109/51.582176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carl P, Schillers H. Elasticity measurement of living cells with an atomic force microscope: data acquisition and processing. European J. Physiology. 2008;457:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maivald P, et al. Using force modulation to image surface elasticities with the atomic force microscope. Nanotechnology. 1991;2:103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahaffy R, Park S, Gerde E, Kas J, Shih C. Quantitative analysis of the viscoelastic properties of thin regions of fibroblasts using atomic force microscopy. Biophysical Journal. 2004;86:1777–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang N, Wong KKH, Bruyn JR, Hutter JL. Frequency-dependent viscoelasticity measurement by atomic force microscopy. Meas. Sci. Techno. 2009;20:703–712. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang R, et al. Motion controller for the atomic force microscopy based nanomanipulation system. IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; St. Louis, MO, USA. 2009. pp. 1339–1344. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alsteens D, Dague E, Rouxhet P, Baulard A, Dufrene Y. Direct measurement of hydrophobic forces on cell surfaces using AFM. Langmuir. 2007;23:977–979. doi: 10.1021/la702765c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim CT, Zhou EH, Quek ST. “Mechanical models for living cells-a review,”. Journal of Biomechanics. 2006;39:195–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingber D, Tensegrity I. Cell structure and hierarchical systems biology. J. of Cell Sci. 2003;116:1157–1173. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han S, Nakamura C, Obataya I, Nakamura N, Miyake J. A molecular delivery system by using AFM and nanoneedle. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2005;20:2120–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Robers K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Sciences; 2008. pp. 1115–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreplak L, Bar H, Leterrier J, Herrmann H, Aebi U. Exploring the mechanical behavior of single intermediate filaments. Journal of Mol. Biol. 2005;354:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanchette C, Loui A, Ratto T. Tip functionalization: applications to chemical force spectroscopy. In: Noy A, editor. Handbook of Molecular Force Spectroscopy. US: Springer; 2008. pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ando T, et al. A high-speed atomic force microscope for studying biological marcomolecules in action. Chemphyschem. 2003;4:1196–1202. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayden O, Bindeus R, Dickert F. Combining atomic force microscope and quartz crystal microbalance studies for cell detection. Measurement Science and Technology. 2003;14:1876–1881. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang R, Xi N, Fung CKM, Qu C, Xi J. Comparative studies of Atomic force microscopy and quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation for real-time identification of signaling pathway. IEEE. Int. Conf. on Nanotechnology; Seoul, Korea. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie H, Régnier S. Parallel imaging/manipulation force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:106–109. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahn Y, Ono T, Esashi M. Micromachined Si cantilever arrays for parallel AFM operations. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology. 2008;22:308–311. [Google Scholar]