Abstract

Background

The nonmedical use of prescription drugs is the fastest growing drug problem in the United States, disproportionately impacting youth. Furthermore, the population prevalence of injection drug use among youth is also on the rise. This short communication examines the association between current prescription drug misuse (PDM) and injection among runaway and homeless youth.

Methods

Homeless youth were surveyed between October, 2011 and February, 2012 at two drop-in service agencies in Los Angeles, CA. Prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between current PDM and injection behavior were estimated. The outcome of interest was use of a needle to inject any illegal drug into the body during the past 30 days.

Results

Of 380 homeless youth (median age, 21; IQR, 17-25; 72% male), 84 (22%) reported current PDM and 48 (13%) reported currently injecting. PDM during the past 30 days was associated with a 7.7 (95% CI: 4.4, 13.5) fold increase in the risk of injecting during that same time. Among those reporting current PDM with concurrent heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use, the PR with injection was 15.1 (95% CI: 8.5, 26.8).

Conclusions

Runaway and homeless youth are at increased risk for a myriad of negative outcomes. Our preliminary findings are among the first to show the strong association between current PDM and injection in this population. Our findings provide the basis for additional research to delineate specific patterns of PDM and factors that enable or inhibit transition to injection among homeless and runaway youth.

Keywords: prescription drug misuse, injection, homeless youth

1. Introduction

The nonmedical use of prescription drugs is the fastest growing drug problem in the United States, resulting in more deaths per year than heroin and cocaine combined (CDC, 2011). In household and school-based surveys, opioid pain relievers are the most commonly misused prescription drug and young people misuse them at alarming rates (Johnston et al., 2013; SAMHSA, 2013). Approximately one in ten persons between the ages of 12 and 25 have engaged in nonmedical use of opioid pain relievers (SAMHSA, 2011). Among high school seniors, reports of past year nonmedical use of tranquilizers and sedatives are approximately 5% (Johnston et al., 2013). Furthermore, evidence is beginning to emerge to suggest that misuse of prescription drugs may represent a new pathway into injection drug use (Inciardi et al., 2009; Lankenau et al., 2012b; Pollini et al., 2011).

However, data on prescription drug misuse (PDM) among homeless and runaway youth is sparse. Homeless and runaway youth are at increased risk for a myriad of negative outcomes including prevalent use of alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine (Baer et al., 2003; Martino et al., 2011; Nyamathi et al., 2012; Rice et al., 2007; Salomonsen-Sautel et al., 2008). Furthermore, homelessness has been shown to independently predict initiation into injection drug use (Feng et al., 2013; Parriott and Auerswald, 2009).

Injection drug use is a major risk factor for acquiring and transmitting blood-borne infections such as HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Young injectors are at particularly high risk for infection (Klevens et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2002). Moreover, the population prevalence of young persons who inject drugs (PWID) appears to be increasing (Tempalski et al., 2013). To help better characterize the increasingly intertwining epidemics of nonmedical use of prescription drugs and injection drug use among young people, we examined the association between current PDM and injection among homeless and runaway youth.

2. Methods

Data were derived from the YouthNet study, a longitudinal study of runaway and homeless youth and young adults aged 13 to 28 who are recruited using an event based approach at two drop-in agencies in Los, Angeles, California. Panel data is collected every six months. During the recruitment period, a consistent set of two research staff members are responsible for recruitment to prevent youth completing the survey multiple times within each data collection period per site.

Study eligibility includes: being at least 13 years of age, able speak English or Spanish, and utilizing services at one of the two drop-in agencies where data was collected. During each panel collection, participants complete an Audio-Computer Assisted Self-Interview survey which assesses sexual history and risk behaviors, drug and alcohol behaviors, mental health, and living situation. In addition, participants completed a face-to-face social network-mapping interview. Participants had the option of refusing to answer any question which they did not want to answer. Signed voluntary informed consent was obtained from each participant (informed consent from participants 18 and older and informed assent from those 13 to 17 years of age as homeless youth are considered unaccompanied minors.) All participants received $20 in cash or gift cards as compensation for their time. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California.

The present study examines baseline data collected between October, 2011 and February, 2012 from 380 participants. The primary outcome is current injection defined as having used a needle to inject any illegal drug into the body in the past 30 days at least once. The main factor of interest is current PDM. To assess current PDM, participants were asked “during the past 30 days, how many times have you taken a prescription drug without a doctor's prescription or used more of the drug or took the drug more often than prescribed? Prescription drugs may include OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, codeine, Adderall, Ritalin, or Xanax.” Both measures were based on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance questions (Brener et al., 2013).

Chi-square (X2) statistics were calculated to assess differences based on current injection status and Fisher's exact test was calculated when minimum expected frequency requirements were not met. Generalized linear models with log link and binomial error distribution were used to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between current injection and PDM. All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

A total of 457 homeless youth and young adults receiving services at two drop-in agencies were approached to participate in the study. Of those approached, a total of 398 (87%) agreed to participate. Of the 380 participants included in the current analysis, approximately 72% were male (Table 1). By race/ethnicity, 36% of participants were white, non-Hispanic, 29% were black, non-Hispanic, and 16% were Hispanic. A total of 48 (13%) participants reported using a needle to inject any illegal drug into their body during the past 30 days. Overall, 84 (22%) participants reported misusing prescription drugs in the past 30 days. Among participants who reported current injection, 33 (69%) also reported current PDM compared to 51 (16%) of participants who were not current injectors. By injection status, participants differed significantly by race/ethnicity. Compared to those who did not report current injection, significantly more participants who reported currently injecting were white (56% vs. 33%, p<0.001).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, current living situation, current illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse (PDM) by injection status among runaway and homeless youth, Los Angeles, California, October 2011-February 2012.

| Current injector n(%) 48 (12.6) | Not current injector n(%) 332 (87.4) | X2 p-value | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAIN FACTOR OF INTEREST | ||||

| Current PDM | ||||

| In past 30 days | 33 (68.8) | 51 (15.5) | <0.001 | 84 (22.2) |

| Not in past 30 days or never | 15 (31.2) | 279 (84.5) | 294 (77.8) | |

| Current PDM and heroin use | ||||

| Both in past 30 days | 23 (60.5) | 8 (2.3) | <0.001 | 31 (9.5) |

| Not in past 30 days or never | 15 (39.5) | 279 (97.2) | 294 (90.5) | |

| Current PDM and cocaine use | ||||

| Both in past 30 days | 17 (53.1) | 12 (4.1) | <0.001 | 29 (9.0) |

| Not in past 30 days or never | 15 (46.9) | 279 (95.9) | 294 (91.0) | |

| Current PDM and meth use | ||||

| Both in past 30 days | 24 (61.5) | 22 (7.3) | <0.001 | 46 (13.5) |

| Not in past 30 days or never | 15 (38.5) | 279 (92.7) | 294 (86.5) | |

| Current PDM, heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use | ||||

| All in past 30 days | 10 (40.0) | 3 (1.1) | <0.001 | 13 (4.2) |

| Not in past 30 days or never | 15 (60.0) | 279 (98.9) | 294 (95.8) | |

| COVARIATES | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 37 (78.7) | 232 (71.0) | 0.267 | 269 (71.9) |

| Female | 10 (21.3) | 95 (29.0) | 105 (28.1) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 27 (56.3) | 109 (32.9) | <0.001 | 136 (35.9) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | --- | 110 (33.2) | 110 (29.0) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (20.8) | 49 (14.8) | 59 (15.6) | |

| Other or mixed race | 11 (22.9) | 63 (19.0) | 74 (19.5) | |

| Age | ||||

| 14 – 18 | 4 (8.3) | 22 (6.6) | 0.303 | 26 (6.8) |

| 19 – 20 | 13 (27.1) | 102 (30.7) | 115 (30.3) | |

| 21 – 22 | 9 (18.7) | 95 (28.6) | 104 (27.4) | |

| 23 – 27 | 22 (45.8) | 113 (34.0) | 135 (35.5) | |

| Current living situation | ||||

| Family home | 2 (4.3) | 30 (9.3) | 0.094 | 32 (8.6) |

| Relative/friend/partner's home | 11 (23.4) | 53 (16.4) | 64 (17.3) | |

| Shelter/group home | 5 (10.6) | 69 (21.3) | 74 (20.0) | |

| Street | 23 (48.9) | 110 (34.0) | 133 (25.8) | |

| Other: e.g. hotel, detention, car | 6 (12.8) | 62 (19.1) | 68 (18.3) | |

NOTE: Categories may not add up to total due to missing data for individual variables.

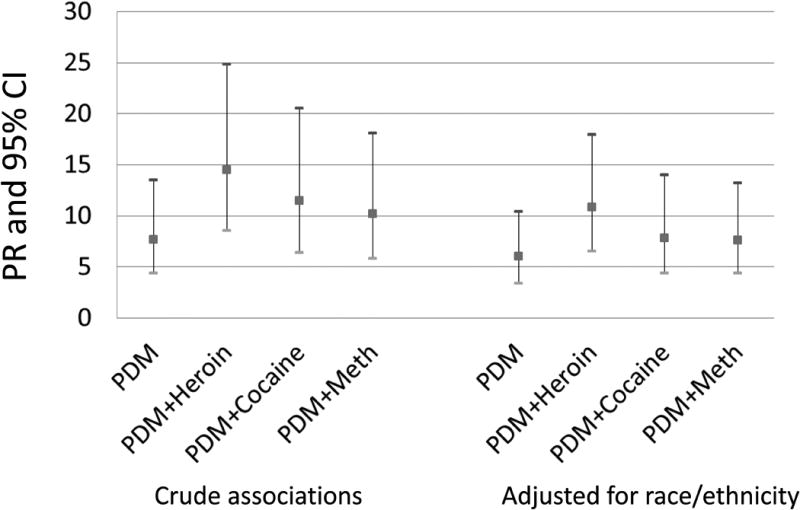

Figure 1 shows the crude and adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% CIs for the association between injection and PDM in the past 30 days. In addition, crude prevalence ratios and 95% CI are presented for the associations between current injection and past 30 day use of PDM and heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Current misuse of prescription drugs was associated with a 7.7 (95% CI: 4.4, 13.5) fold increase in the risk of current injection. Comparatively, the association is stronger for current PDM with heroin, current PDM with cocaine, and current PDM with methamphetamine and injection with crude prevalence ratios of 14.5 (95% CI: 2.5, 24.8), 11.5 (95% CI: 6.4, 20.5), and 10.2 (95% CI: 5.8, 18.0), respectively. When adjusting for race/ethnicity, the prevalence ratios between PDM and injection are slightly attenuated.

Figure 1.

Crude and adjusted associations between current prescription drug misuse and injection status among runaway and homeless youth, Los Angeles, California, October, 2011-February, 2012.

4. Discussion

In our sample of homeless and runaway youth, current prescription drug misuse was strongly associated with current injection. Furthermore, these preliminary data show that PDM is intricately intertwined in the complicated drug use patterns of homeless youth. Although our focus was to describe the relationship between PDM and injection, only 2 participants who were current injectors reported PDM without concurrent use of other substances which further underscores how intertwined PDM and illicit drug use have become.

Overall, 12.6% of our sample reported current injection. In other studies representative of homeless youth, estimates of injection drug use vary from 3.8% among non-travelling or non-migratory homeless youth to 19.4% among migratory youth (Martino et al., 2011) and 4.7% among newly homeless youth (i.e. homeless for less than 6 months) to 25.4% among experienced homeless (i.e. homeless for more than 6 months; Milburn et al., 2006). With the exception of Lankenau's study (2012a) among prescription drug using young adults of whom a proportion reported being homeless, we are unaware of estimates of prescription drug misuse among representative samples of homeless youth. In our sample of homeless and runaway youth, 22.2% reported misuse of prescription drugs in the past 30 days. Our results contribute to the modest, but growing scientific literature, documenting the association between injection and PDM with a particular focus on an underrepresented at-risk population.

Our findings are subject to limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional and we did not include questions to ascertain whether the misuse of prescription drugs occurred before or after initiation of injection behavior. Delineating the onset and progression of PDM and its relation to other substance use and injection is critical to understanding this emerging drug use pattern. Second, we did not ask what drug participants were injecting. Our injection question simply captured whether or not the participant had used a needle to inject any illegal drug into their body. It is possible that some participants may have underreported injection if they only injected prescription drugs believing that prescription drugs are legal. However, given the intermediate steps associated with preparing and apportioning prescription drugs for injection, the risk for HCV transmission is particularly high for persons who are injecting prescription drugs (Roy et al., 2012). Though we did not test for HIV and HCV as part of the study, 8 participants self-reported being HIV positive and 2 reported being HCV positive. Third, the current analysis is a descriptive analysis of the baseline data and does not represent the rich social network context within which the data was collected.

These preliminary findings, along with the handful of studies documenting this emerging drug use pattern, signify the need for prospective studies that provide comprehensive data to characterize the transition from prescription drug misuse to injection among youth and young adults.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Mental Health (R01 MH093336) to Dr. Eric Rice. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors thank the YouthNet study team at the USC School of Social Work for collecting this important data and the research participants for providing it.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA undertook the literature review, data analysis, and writing of this brief communication. ER and HR designed the parent study, were responsible for data collection, and contributed to the analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of this brief communication and have approved of the final communication.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have financial or personal disclosures to make.

Parts of this research were presented at the 2013 Society for Prevention Research Conference.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer JS, Ginzler JA, Peterson PL. DSM-IV alcohol and substance abuse and dependence in homeless youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kinchen S, Eaton DK, Hawkins J, Flint KH. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System--2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers---United States, 1999--2008. MMWR. 2011;60:1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Mathias S, Montaner J, Wood E. Homelessness independently predicts injection drug use initiation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Beard RA. Prescription opioid abuse and diversion in an urban community: the results of an ultrarapid assessment. Pain Med. 2009;10:537–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Drug Use: 2012 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klevens RM, Hu DJ, Jiles R, Holmberg SD. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Schrager SM, Silva K, Kecojevic A, Bloom JJ, Wong C, Iverson E. Misuse of prescription and illicit drugs among high-risk young adults in Los Angeles and New York. J Public Health Res. 2012a;1:22–30. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2012.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Jackson Bloom J, Harocopos A, Treese M. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2012b;23:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Tucker JS, Ryan G, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Munjas B. Increased substance use and risky sexual behavior among migratory homeless youth: exploring the role of social network composition. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40:1634–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9646-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rice E, Mallet S, Rosenthal D. Cross-national variations in behavioral profiles among homeless youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Tyndall M, Spittal P, Li K, LaLiberte N, Schechter MT. HIV incidence and associated risk factors among young injection drug users. AIDS. 2002;16:491–493. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200202150-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Hudson A, Greengold B, Leake B. Characteristics of homeless youth who use cocaine and methamphetamine. Am J Addict. 2012;21:243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parriott AM, Auerswald CL. Incidence and predictors of onset of injection drug use in a San Francisco cohort of homeless youth. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1958–1970. doi: 10.3109/10826080902865271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, Banta-Green CJ, Cuevas-Mota J, Metzner M, Teshale E, Garfein RS. Problematic use of prescription-type opioids prior to heroin use among young heroin injectors. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2011;2:173–180. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S24800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2007;19:697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Arruda N, Leclerc P, Haley N, Bruneau J, Boivin JF. Injection of drug residue as a potential risk factor for HCV acquisition among Montreal young injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsen-Sautel S, Van Leeuwen JM, Gilroy C, Boyle S, Malberg D, Hopfer C. Correlates of substance use among homeless youths in eight cities. Am J Addict. 2008;17:224–234. doi: 10.1080/10550490802019964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Pouget ER, Cleland CM, Brady JE, Cooper HL, Hall HI, Lansky A, West BS, Friedman SR. Trends in the population prevalence of people who inject drugs in US metropolitan areas 1992-2007. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]