Abstract

We used an established microsimulation model, quantified to a rural South African setting with a well-developed antiretroviral treatment program, to predict the impact of antiretroviral therapy on the HIV epidemic in the population aged 50+. We show that the HIV prevalence in patients aged 50+ will nearly double in the next 30 years, while the fraction of HIV infected patients aged over 50 will triple in the same period. This ageing epidemic has important consequences for the South African health-care system, as older HIV patients require specialized care.

Keywords: HIV, Antiretroviral therapy, Ageing, Mathematical model, Epidemiological trends

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is changing the character of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. At the individual level, ART has increased survival of those infected. At the population level, widespread availability of ART could result in the overall ageing of the infected population. ART use in sub-Saharan Africa is expanding rapidly, with an estimated 3.9 million patients on treatment in 2009 [1]. Estimates show that there are already about 3 million people over 50 years living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. Recently, Mills et al argue for more attention to be paid to HIV infected older people in terms of prevention and care [3]. In the United States, estimates from the CDC show that about 29% of the entire population living with HIV was aged over 50 years in 2008 [4], and projections show that in about 5 years time, more than half of all HIV infected patients will be aged over 50 years [5]. Although it is clear that the number of HIV infected elderly (aged over 50) in sub-Saharan Africa will rise as a result of the ART roll-out, the magnitude of this phenomenon has not yet been quantified. One of the countries most likely to be confronted with this shifting epidemic is South Africa, where nearly 6 million people are estimated to be HIV infected, of whom 970,000 were on ART in 2009 [6]. HIV prevalence in the population aged over 50 in South Africa is estimated at about 9% [2, 7].

Methods

To predict the impact of the current ART roll-out on age- and sex-specific HIV prevalences in South Africa up to 2040, we used an established mathematical model (STDSIM) that simulates individuals in a dynamic network of sexual contacts [8, 9]. The model is tailored to the Hlabisa sub-district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (Supplementary Digital Content). This area has a high HIV prevalence [10] and a well-developed ART program [11, 12]. In the model, the survival of ART-naïve HIV infected patients is on average 10 years. We assumed ART to increase survival from start of treatment by a factor 3 and decrease infectivity by 92%, as observed in recent studies [13, 14]. We assumed ART to be initiated at CD4 cell counts of ≤200 cells/μL in the period 2004 - 2010, and ≤350 cells/μL in 2011, according to the new WHO guidelines [15]. The model contains an age-specific partner change rate, and frequency of intercourse within a sexual relationship. In previous applications of our model [9] decreasing trends of sexual activity by age in the population aged 15-49 were simply extrapolated to the over-50 group because of lack of available data on sexual behaviour in the population aged 50+. This resulted in a negligible level of risk behaviour and HIV-incidence in the over-50 group, which is inconsistent with recent local data in terms of HIV prevalence in this group [7]. Therefore, we now assumed partner acquisition rates to remain at the same level from age 45 onwards, while the frequency of sexual contacts within a relationship is reduced by 25% for those aged over 50. The ART roll-out in Hlabisa is part of the South African national ART roll-out aimed at achieving universal coverage. Therefore, we assume that the impact of ART on the course of the epidemic is not affected by migration.

Results

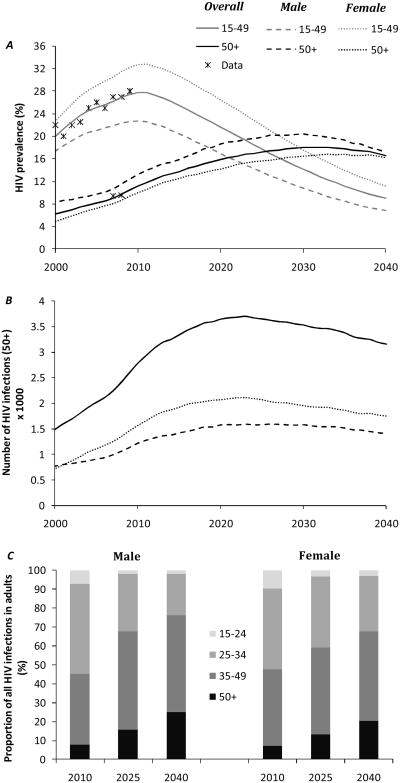

Figure 1A shows the projected trends in HIV prevalence in the population aged 15-49 and 50+ in Hlabisa. While HIV prevalence in the 15-49 group would more than halve in the period 2010-2040 from 28% to 9%, the HIV prevalence in the population aged 50 years and older is estimated to nearly double in the same period, from about 9% (8% in women; 11% in men) to 17% (16% in women; 17% in men). The total number of HIV infections in those aged over 50 is expected to have increased by 51% in 2025 (49% for men; 53% for women), after which the number of HIV infections in this age group remains relatively stable (figure 1B). The absolute number of HIV infections in the elderly is estimated to even have doubled by 2025 when comparing to 2004, the year the ART roll-out in the area started. As a result, the age distribution of HIV infected patients would change considerably (figure 1C). This is especially true for men, where currently less than 1 in 12 HIV infected people is aged over 50; in 2040 this would be 1 in 4.

Figure 1. HIV prevalence (in the 15-49 and 50+ age groups), total number of infections, and age distribution of HIV infected patients over the period 2000-2040 in the Hlabisa sub-district of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, predicted with the STDSIM model.

A = HIV prevalence in those aged 15-49 and 50+ years. Data points from HIV surveillance in Hlabisa [5, 7], B = Absolute number of HIV infections among the population aged 50+ in the Hlabisa sub-district (total population size approximately 280,000 in 2009), C = Age distribution of HIV infected men and women in 2010, 2025 and 2040.

Discussion

We show that the number of HIV infected elderly will increase substantially over the coming decades. This will further complicate an ongoing epidemiological transition in South Africa, where projections show that, despite the excess mortality due to HIV, the population aged over 60 years is estimated to more than double by 2030 due to lower all-cause mortality rates [16]. Cardiovascular risk factors are already prevalent among South African adults, with high levels of obesity, hypertension, and cigarette smoking [17]. In addition, HIV infection and ART have been found to be further independent risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and other age-related chronic conditions [18]. The ageing of the HIV epidemic will also have important consequences for the organization of HIV care and prevention. Treated HIV is a chronic condition interacting with and accelerating ageing. Co-morbidities, interactions with other drugs, and drug toxicity complicate antiretroviral treatment in the elderly, who often require individualized regimens and careful monitoring [18]. Furthermore, disease progression increases with age at acquiring HIV, and effectiveness of ART is lower in people initiated at an older age than at younger age [18]

The above-mentioned processes are not accounted for in the model, however, it is unlikely that they will severely affect our results. A reduced effectiveness of ART and thus increased transmission probability of HIV, coupled with the expected lower all-cause mortality [16], may result in an even more substantial increase in the number of HIV infected elderly compared to our model predictions. On the other hand, our assumption that the full WHO treatment guidelines will be implemented in 2011 will result in a slight overestimation of the number of HIV infected elderly, since under the current South African ART policy only pregnant women and TB infected patients are eligible for ART at ≤350 cells/μL, while for others the ≤200 cells/μL threshold remains for the time being. Furthermore, disease progression is generally faster in the elderly [18], but this is likely to have a limited impact on our predictions since these patients often die of other causes. Finally, we did not consider the impact of ART and HIV on the population growth in the area because long-term projections on population size and structure would require additional assumptions regarding future changes in fertility and background mortality rates which are not only influenced by HIV and ART, but also other processes such as economic growth, and political and economic stability.

We used a 92% reduction in infectivity due to ART and a factor 3 increase in ART naive based on the best available estimates, but some argue that this might be overly optimistic [19]. If we assume an 80% reduction instead, HIV prevalence in the population aged over 50 will increase even further to about 26% in 2040, and the total number of HIV infected individuals aged over 50 will have doubled by 2040 (results not shown). Also, increased survival benefits [20] will result in a further increase in the HIV prevalence (to 25% in 2040) and the total number of HIV infected elderly (a 90% increase in 2040 compared to 2010). The proportion of HIV infected patients aged over 50 only changes slightly under these alternative assumptions (results not shown).

In conclusion, we show that the HIV epidemic in South Africa is at a critical turning point. While the number of infections among young people will continue to decline [6], the number of HIV infections in the elderly can be expected to increase by about 50% in the next fifteen years. In the near future this group will need to be an important focus of attention, and creative solutions need to be found to alleviate further stress placed on an already overburdened health system through the increased need for specialized care, and interacting with other public health problems of an ageing population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work is supported by the National Institute of Health [1R01MH083539-01 to Dr. M. Lurie] and grants from the Wellcome Trust to the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa 082384/Z/07/Z. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. In addition, this study is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the President's Emergency Plan (PEPFAR) under the terms of Award No. 674-A-00-08-0001-00 for the Hlabisa Treatment and Care Programme. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Contributors: JACH, MNL, and SJdV performed the main analysis, interpreted the results anddrafted the manuscript. RB (1) assisted in developing the model and interpreting the results. MLN, FT, TB and RB (2) assisted in interpreting the results and drafting the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.WHO. progress report 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negin J, Cumming RG. HIV infection in older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: extrapolating prevalence from existing data. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:847–53. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills EJ, Rammohan A, Awofeso N. Ageing faster with AIDS in Africa. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62180-0. Published online first: Nov 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Vol. 20. Atlanta: Centers fo Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Published: June 2010 [22/10/2010]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2008report/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Aug 15;47(4):542–53. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS. [Accessed: 12/12/2010];Report on the Global AIDS epidemic. 2010 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/GlobalReport/Global_report.htm.

- 7.Wallrauch C, Barnighausen T, Newell M. HIV prevalence and incidence in people 50 years and older in rural South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:812–4. doi: 10.7196/samj.4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korenromp EL, Van Vliet C, Bakker R, De Vlas SJ, Habbema JD. HIV spread and partnership reduction for different patterns of sexual behavior – a study with the microsimulation model STDSIM. Math Pop Studies. 2000;8:135–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orroth KK, Freeman EE, Bakker R, Buve A, Glynn JR, Boily MC, et al. Understanding the differences between contrasting HIV epidemics in east and west Africa: results from a simulation model of the Four Cities Study. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(1):i5–16. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanser F, Hosegood V, Barnighausen T, Herbst K, Nyirenda M, Muhwava W, et al. Cohort Profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:956–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke GS, Tanser FC, Barnighausen TW, Newell ML. Population uptake of antiretroviral treatment through primary care in rural South Africa. BMC public health. 2010;10:585. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houlihan CF, Bland R, Mutevedzi P, Lessells RJ, Ndirangu J, Thulare H, et al. Cohort Profile: Hlabisa HIV treatment and care programme. Int J Epidemiol. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp402. Published ahead of print: Feb 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walensky RP, Wolf LL, Wood R, et al. When to start antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:157–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnell D, Baeten J, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Rapid Advice: Antiretroviral Therapy For HIV Infected In Adults And Adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tollman SM, Kahn K, Sartorius B, Collinson MA, Clark SJ, Garenne ML. Implications of mortality transition for primary health care in rural South Africa: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet. 2008;372:893–901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61399-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sliwa K, Wilkinson D, Hansen C, Ntyintyane L, Tibazarwa K, Becker A, et al. Spectrum of heart disease and risk factors in a black urban population in South Africa (the Heart of Soweto Study): a cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371:915–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Ge Z, Luo J, et al. HIV Transmission risk among serodiscordant couples: a retrospective study of former plasma donors in Henan, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:232–238. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9b6b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson KA, Robberstad B, Norheim OF. Further benefits by early start of HIV treatment in low income countries: survival estimates of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.