Abstract

We determined the specialty, geographic location, practice type and treatment capacity of waivered clinicians in Washington State. We utilized the April 2011 Drug Enforcement Agency roster of all waivered buprenorphine prescribers and cross-referenced the data with information from the American Medical Association and online resources. Waivered physicians, as compared to Washington State physicians overall, are more likely to be primary care providers, be older, less likely to be younger than 35years, and more likely to be female. Isolated rural areas have the lowest provider to population ratios. Ten counties lack either a buprenorphine provider or a methadone clinic. In rural areas, waivered physicians work predominately in federally-subsidized safety-net settings, which underscores the need for continued governmental support of primary care and mental health in these settings.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Rural, Washington, Opioid abuse treatment

1. Introduction

The dramatic increase in the prescription of opioids for chronic pain in the last two decades has left in its wake an increased number of patients who are opioid tolerant, addicted or dead. Between 1997 and 2005, the number of methadone doses prescribed for pain increased by 1042% and the number of doses of oxycodone increased by 500% (Drug Enforcement Administration, 2007). From 1999 to 2007, unintentional drug overdose deaths associated with prescription opioids rose by 395% (Centers for Disease Control, Prevention [CDC], 2010). Disturbingly, opioid misuse is now common among adolescents, including those in rural areas (Lambert, Gale, & Hartley, 2008). The 2010 Washington State Healthy Youth Survey found 8% of 10th graders reported using prescription opioids to “get high” in the last 30days after obtaining the medications from a friend, a family member or misusing their own prescription (Banta-Green, 2011).

Prolonged use of prescription opioids in high doses for chronic pain can lead to other adverse health effects including general pain sensitization and an increase in falls. These adverse outcomes have a high and rising societal cost: The CDC estimated that costs associated with prescription opioid abuse in the United States were $9.5 billion in 2005 (CDC, 2010). By 2010 the estimates of the societal costs of prescription drug abuse had increased to more than $55 billion (Birnbaum, White, Schiller, Waldman, Cleveland, & Roland, 2011).

Current treatment approaches are based on the evidence that demonstrates that opioid dependence is a chronic, relapsing disease (Leshner, 1997). Clinical treatment goals are to eliminate the use of illicit opioids, to reduce the dose of prescribed opioids to safe levels, to promote mental health and to prevent relapses. The most effective therapy in achieving these goals is opioid replacement therapy (ORT) (National Institutes and of Health, 1998), which typically combines a maintenance medication of methadone or buprenorphine with supportive counseling services. In contrast to ORT success rates of about 50%, treatment with detoxification alone is likely to be ineffective in preventing relapse (O'Connor, 2005). Weiss et al. (2011) found that 49.2% of his 360 patients had successful outcomes during extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment in contrast to 8.6% (31 of 360) for those who were tapered. Interestingly, counseling did not improve treatment success beyond biweekly standard medical care visits.

Buprenorphine/naloxone has several advantages over methadone in the treatment of addiction to prescription opioids. As a partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine is less likely to contribute to unintentional overdoses than methadone, and when combined with naloxone does not result in a “high” if used parenterally.

Another major advantage of buprenorphine/naloxone is that waivered physicians can prescribe this form of ORT in their offices. This waiver allows them to treat up to 30 patients in the first year, with the option to treat up to 100 patients in subsequent years. In contrast, physicians cannot prescribe methadone for the treatment of addiction. Methadone can only be dispensed in federally regulated opioid treatment programs, which are primarily in urban areas. As a consequence, methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is virtually unavailable in most rural areas. Those relatively few rural patients who do travel to urban methadone clinics often have their lives disrupted given the need for observed dosing several times a week. In the state of Washington the absence of rural access to MMT is also a financial burden for payers: the State of Washington Medicaid program currently spends $3 million a year to transport rural patients to urban methadone clinics (J. Thompson, Chief Medical Officer, Health Care Authority of Washington, personal communication, August 15, 2011).

For rural patients who do not need the structure of daily observed methadone clinics, office based buprenorphine treatment is a promising option for treatment. However, rural residents are more likely to be uninsured than their urban counterparts (Department of Health [DOH], 2008) and may rely heavily on primary care providers in safety net facilities such as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), community health centers (CHCs), rural health clinics (RHCs), and critical access hospitals (CAHs). However, little is known about the availability of buprenorphine treatment in these rural safety-net settings.

The purpose of this study was to determine the availability of buprenorphine treatment in Washington State by characterizing the geographic location, specialty, practitioner's age, number of treatment slots and organizational status of the practices of waivered physicians. Washington State is a large western state that sponsors a five-state regional medical school (the WWAMI program) and thus has a major influence on patterns of practice throughout the region. We sought to answer four questions of interest:

What are the predominant specialties of waivered physicians in urban and rural areas?

In what type of clinics do waivered physicians practice?

Is there is a relative shortage of buprenorphine-waivered physicians in rural areas, as measured by provider to population ratios, and population to treatment slot ratios?

Are waivered physicians different in age and sex from the overall physician population age in Washington State?

2. Materials and methods

The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study. We purchased the April 2011 Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA, US Department of Justice, 2011) roster of all buprenorphine-waivered physicians from the federal government. This roster includes the number of treatment slots (either 30 or 100) and an address for each provider.

2.1. Name of facility

We used the DEA list to obtain addresses of waivered providers. Of the addresses of waivered physicians on the DEA list, 136 either stated the name of the facility (102) or listed a Seattle address of a known teaching or public hospital (34). If a facility name was not listed, we used googlemaps.com to confirm that the address was a hospital or clinic for an additional 210 addresses. We looked up the practice locations of the remaining 81 physician names on Healthgrades.com and phoned providers' offices to confirm that the facility corresponded to the waivered physician. Nine of the physicians had no facility data available and no working phone number on Healthgrades.com.

2.2. Medical specialty

We obtained the medical specialty for 307 of the 427 waivered providers by matching the DEA file with the 2004 American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile. For the remaining 120 providers, we found specialty information on the AMA Doctorfinder, (2011) For Patients (108) and the Healthgrades.com (12) Web sites.

2.3. Age and sex

Provider age and sex were obtained from the AMA Masterfile (307) or from Healthgrades.com (48 for age, 102 for sex). No age could be found on 72 providers, and no sex could be confirmed for 18 providers. The age distribution of the Washington State providers was obtained from the annual publication of the AMA (Smart, 2011).

2.4. Specialty assignment

We were able to assign 417 of the 427 waivered physicians to a specific specialty, using the AMA Masterfile. We further aggregated the specialties into four clinically relevant groups, as shown in Table 1. “Primary care” was defined to include family medicine and internal medicine; “specialty care” included psychiatry, physical medicine and rehabilitation, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, addiction medicine, and an additional 18 “other” specialties with fewer than five waivered physicians. We were unable to identify a specialty for 10 physicians and classified their specialty as “unknown.”

Table 1.

Primary specialty listings of waivered providers and potential treatment slots available by specialty in Washington State.

| Total = 427 % of waivered providers |

Primary specialty and number of specialists |

Adjusted specialty | Providers (N = 427), n (%) |

Tx slots (N = 18,760), n (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care (n = 213, 49.9%) | Family medicine, 149 | Family medicine | 171 (40.1) | 7790 (41.7) |

| Family practice, 16 | ||||

| General practice, 6 | ||||

| Int. medicine, geriatrics, 1 | Internal medicine | 42 (9.8) | 1750 (9.4) | |

| Internal medicine, 41 | ||||

| Specialty care (n = 204, 47.8%) | Psychiatry, 103 | Psychiatry | 126 (29.5) | 5390 (28.9) |

| Child and adolescent, 16 | ||||

| Addiction and other psychiatry, 10 | ||||

| Anesthesiology, pain, 1 | Anesthesiology | 16 (3.8) | 620 (3.3) | |

| Management anesthesiology, 15 | ||||

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation, 21 | Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 21 (4.9) | 980 (5.2) | |

| Emergency medicine, 8 | Emergency medicine | 8 (1.9) | 380 (2.0) | |

| Addiction medicine, 5 | Addiction medicine | 5 (1.2) | 290 (1.6) | |

| Other specialties, 18 | Other | 28 (6.6) | 1120 (6.0) | |

| Specialty unknown (n = 10, 2.3%) | Unknown, 10 | Unknown | 10 (2.3) | 440 (2.4) |

Providers can have a maximum of 30 or 100 patients.

Greater than 100% due to rounding.

2.5. Rural or urban practice status

We used rural–urban commuting area (RUCA) codes 2.0 developed by the United States Department of Agriculture and the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center to characterize the rural or urban nature of the practices (Rural Health Research Center, 2005). The RUCA codes enabled us to characterize each waivered prescriber's practice location as reflected in their zip codes as urban, large rural, small rural or isolated rural.

2.6. Practice organizational type

We matched the facility names with the 2011 Washington State DOH lists of safety net facilities and residency clinics to categorize the practices as a “private,” “safety net,” “other,” or “unknown” practice type. Practices named after the active physicians were assumed to be private practices. Practices of retired physicians and practices in correctional or military clinics were listed as “other.” We listed the status of 21 clinics as “unknown.” These clinics were not listed as a residency or safety net clinic, were unreachable by telephone, or had staff that did not know their clinic's status. Information summarizing the type of practice is found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of buprenorphine-waivered physicians, by RUCA geographic code, specialty and residency program status.

| Specialty codes | RUCA code | Total | Subset within residency programs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Large rural |

Small rural |

Isolated rural |

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number and % of waivered providers | 376 (88.1) | 21 (4.9) | 21 (4.9) | 9 (2.1) | 427 (100) | 31 |

| FM | 136 (36.2) | 11 (52.4) | 16 (76.2) | 8 (88.9) | 171 (40.1) | 20 (65) |

| IM | 39 (10.4) | – | 2 (9.5) | 1 (11.1) | 42 (9.8) | 1 (3) |

| PSY | 118 (31.4) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | – | 126 (29.5) | 6 (19) |

| PM&R | 21 (5.6) | – | – | – | 21 (4.9) | – |

| AN | 16 (4.3) | – | – | – | 16 (3.8) | – |

| EM | 6 (1.6) | 2 (9.5) | – | – | 8 (1.9) | – |

| ADM | 5 (1.3) | – | – | – | 5 (1.2) | – |

| Other specialty | 25 (7.5) | 3 (14.3) | – | – | 28 (6.6) | 3 (10) |

| Unknown | 10 (2.7) | – | – | – | 10 (2.3) | 1 (3) |

| Total | 376 (100) | 21 (100) | 21 (100) | 9 (100) | 427 (100) | 31 |

FM- Family Medicine, IM- Internal Medicine, PSY- Psychiatry, PM&R- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, AN- Anesthesiology, EM- Emergency Medicine, ADM- Addiction Medicine.

2.7. Data analysis

We report descriptive statistics for physician specialty, practice, number of treatment slots, age, geographic setting and sex. We categorized the age ranges of waivered physicians (<35 years, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, >65 and unknown) to match age groupings of the Washington State licensed physicians printed yearly by the AMA (Smart, 2011). When appropriate, we performed chi-square tests to determine if the characteristics and settings of the population of waivered providers differed significantly from those of all physician providers.

3. Results

There are 427 waivered physicians in Washington State listed on the April 2011 list.

3.1. The majority of waivered physicians are primary care physicians (family practice and internal medicine physicians)

As shown in Table 1, primary care physicians make up 49.9% of all buprenorphine-waivered providers in the state, while specialists constitute 47.8% of waivered physicians. Family medicine is the most common specialty (40.1%) followed by psychiatry (29.5%).

3.2. Primary care physicians are virtually the only waivered providers in rural parts of the state; almost all waivered specialists are located in urban areas

As seen in Table 2, family medicine physicians represent the largest single specialty group in each type of geographic area, and constitute the majority of the waivered providers in rural portions of the state. The portions of buprenorphine prescribers who are primary care physicians show striking variation across the urban–rural continuum. Family medicine clinicians make up 36% of all buprenorphine-waivered providers in urban areas, but are the majority in rural areas. The proportion of waivered physicians who are family medicine providers increases with rurality: 52% in large rural areas, 76% in small rural areas, and 89% in isolated rural areas. Psychiatrists—the second largest group of waivered physicians—show the opposite pattern, representing 31% of waivered physicians in urban areas, 24% in large rural, 14% in small rural, and 0%of providers in isolated rural areas. All other specialists constitute 20% of waivered physicians in urban areas, but are non-existent in the small rural and isolated rural communities.

3.3. Is there a relative shortage of buprenorphine-waivered physicians in rural areas compared to urban areas?

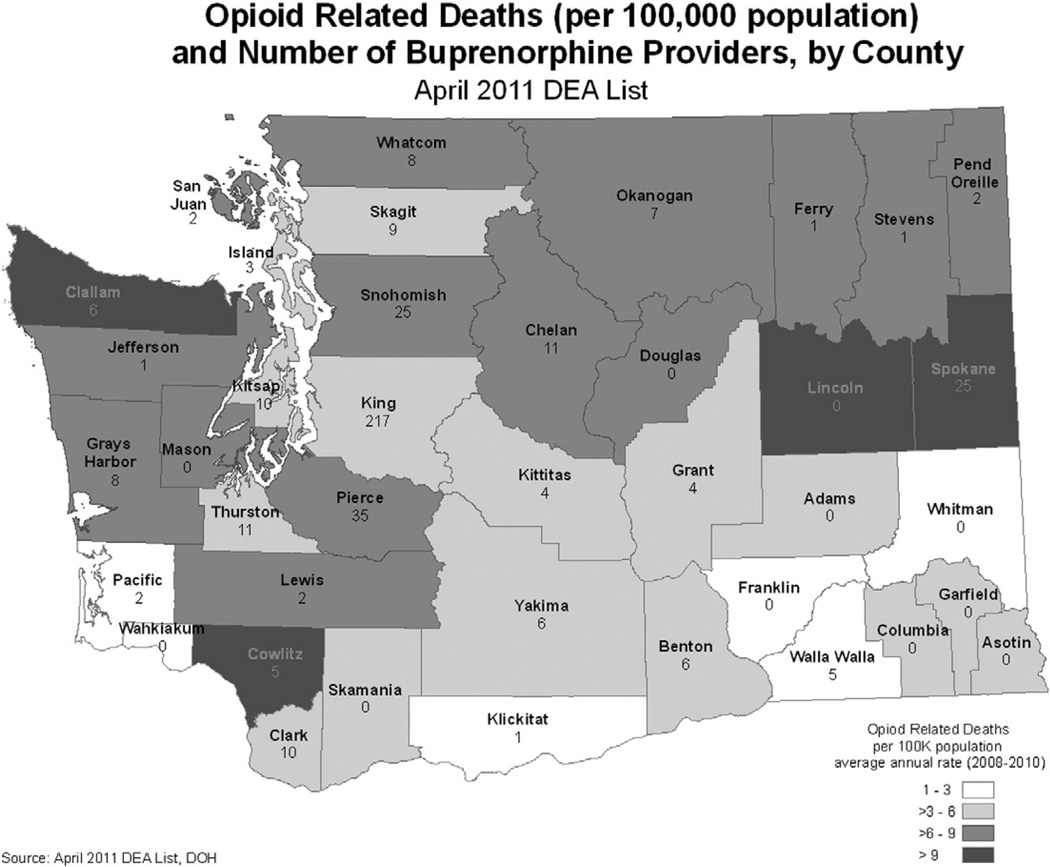

Fig. 1 maps the distribution of MMT and buprenorphine maintenance therapy (BMT) by county. At the time of the study, 32 of the 39 counties lacked methadone maintenance programs and 11 counties lacked providers who could prescribe buprenorphine for addiction. Some 28.1% of the population lacked MMT in their county and 7.0% lacked both MMT and BMT. The counties lacking these services were all rural counties.

Fig. 1.

Washington State counties with ORT options as of April 2011. In Washington State, 28% of the population lives in a county without MMT and 7% of the population lives in a county without MMT or BMT.

Table 3 shows the geographic distribution of waivered physicians and potential treatment slots, compared to the distribution of the population in the state. We use the presence of a provider and the number of slots as surrogate indicators for access to buprenorphine treatment. The overall distribution of waivered physicians and treatment slots was not statistically different than the distribution of the general population in Washington State in urban, large rural, small rural or isolated rural settings (p = .762, Pearson's χ2 = 1.163, df = 3). However, the ratios of buprenorphine providers to the total population in each setting differed (p = .012, Pearson's χ2 = 10.92, df = 3). Surprisingly, small rural areas had the largest number of treatment slots per population, and the isolated rural areas had the fewest number of treatment slots.

Table 3.

Washington State population, waivered providers and treatment slots by 2005 RUCA 2.0 geographic code.

| Variable | Urban | Urban Large rural |

Small rural |

Isolated rural |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington State Population 2010a | 5,756,206 (85.6%) | 511,065 (7.6%) | 215,185 (3.2%) | 242,083 (3.6%) | 6,724,540 (100%) |

| Buprenorphine-waivered providers | 376 (88.1%) | 21 (4.9%) | 21 (4.9%) | 9 (2.1%) | 427 |

| Treatment slots April 2011 DEA list | 16,810 (89.6%) | 840 (4.5%) | 770 (4.1%) | 340 (1.8%) | 18,760 |

| Population to buprenorphine/provider ratios | 15,309:1 | 24,336:1 | 10,247:1 | 26,898:1 | 15,748:1 |

| Population to treatment slot ratio | 342:1 | 608:1 | 279:1 | 712:1 | 358:1 |

Population source: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/53000.html.

3.4. Waivered physicians were disproportionately located in private settings in urban areas and in safety net settings in isolated rural areas

In urban areas, buprenorphine-waivered physicians were predominately in private practices as seen in Table 4. However, in isolated rural areas, waivered physicians were predominately in safety net settings. The distribution of provider types differed significantly by location type (p<.0001, χ2 = 70.4, df = 6). The ratio of waivered physicians in safety net settings to those in private practices was roughly 1:4 in the urban category, to 1:1 in large rural, 3:1 in small rural, and 8:1 in the isolated rural category. Facilities classified as “other” practice, made up 8% (36/427) of practices in urban areas and were present in insignificant numbers in the rural landscape. Residency clinics, a subset of “other” practices in Table 2, have 7% (31/427) of all waivered physicians. Of those 31 physicians, 21 were in family medicine residencies, 6 in psychiatry residencies, 1 in an internal medicine residency, and 4 in unspecified residencies. The practice status of 21 other providers (5%) was unknown. Overall, 88% (376/427) of practices with at least one buprenorphine provider were located in urban areas, which in turn had about 86% of the population. There were 21 large rural, 21 small rural and 9 isolated rural practices with a waivered provider (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Classification of facilities of buprenorphine-waiver ed physicians.

| Variable | Type of clinic | N = 427, n (%) | Classification assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety-net (n = 96, 22%) | FQHC | 24 (6) | CHCsa |

| RHC | 25 (6) | RHCsa | |

| CAH | 7 (2) | CAHsa | |

| Tribal | 13 (3) | Tribal Clinics, including Indian Health Service clinics and tribally-owned clinics | |

| Government-owned hospital | 15 (4) | – | |

| Non-profit safety net | 12 (3) | Any not-for-profit, non-governmental entity with a stated goal to serve the entire population | |

| Private (n = 274, 64%) | Private | 181 (42) | Proprietary clinics in urban areas, polyclinics, and specialty clinics |

| Other hospital | 93 (22) | Either the hospital or hospital owned, non-governmental clinic | |

| Other (n = 36, 8%) | Residency clinic | 31 (7) | Address at known residency clinic or self-defined “residency program” in DEA address |

| Other | 6 (1) | Military clinics, jails, or known retirees | |

| Unknown (n = 21, 5%) | Unknown | 20 (5) | Unreachable |

Note: <100% due to rounding.

Source for facility types: Washington State DOH.

Fig. 2.

Percentage distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in four geographic settings by practice type, n = 406. Information was unknown for an additional 21 or 5% of the 427 practices.

3.5. Buprenorphine-waivered physicians were predominately male and may be older, and less likely to be under 35years of age

Buprenorphine providers are predominantly male (68%). The age distribution is shown below in Table 5. The distribution of buprenorphine-waivered physicians differs from the overall physician population in Washington State. However because the age of 72 (16.9%) of the waivered providers is unknown, we must be cautious in making definitive conclusions about age distribution.

Table 5.

Age of buprenorphine-waivered physicians in Washington, April 2011.

| Agea ranges |

Buprenorphine providers (%) |

Non-waivered providers (%) |

Total patient care providers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <35 | 16 (3.7) | 2307 (11.0) | 2323 (10.9) |

| 35–44 | 78 18.3) | 4670 (22.3) | 4748 (22.3) |

| 45–54 | 79 (18.5) | 4787 (22.8) | 4865 (22.8) |

| 55–64 | 128 (30) | 4613 (22.0) | 4741 (22.2) |

| >65 | 54 (12.6) | 4606 (22.0) | 4660 (21.8) |

| Unknown | 72 (16.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 427 | 20,982 | 21,337 |

Chi-squared goodness of fit test, n = 355. χ2 51.98, 4 df, p<.001.

4. Discussion

The DEA list lags behind the current number of persons who have completed their training for a waiver, so we may slightly underestimate the number of waivered providers in Washington State. The presence of a waivered physician and the number of potential treatment slots represent the upper limit of the possible number of persons who can be treated, and in reality, the number of patients treated will be considerable fewer. Some waivered physicians choose not to prescribe buprenorphine, and if they do prescribe, most treat fewer patients than their limit. In the only national survey on the subject, even those with a waiver to treat 100 patients served an average of only 39 patients (Arfken, Johanson, di Menza, & Schuster, 2010).

We may underestimate the availability of providers in some counties because the DEA list provides only one practice address, while some providers work in multiple settings. We based the clinic's rural–urban status on the zip code in the DEA list, and if the provider works at multiple sites, some counties could actually have services of a physician offering BMT where none was reported in this paper. Some providers on the DEA list were not found on the 2004 AMA Masterfile we used or on the AMA Doctorfinder for patients or Healthgrades.com Web sites. The lack of an age for 17% of the waivered physicians weakens our ability to contrast the ages of buprenorphine providers with the ages of the non-waivered physicians in Washington State.

RUCA status of some zip codes may have changed in the last 5years. We used latest population data that had RUCA codes available to us, and applied this distribution to the 2010 census data. The classification of clinic status within the safety net providers may be imprecise. The source used from the DOH did not differentiate between locally funded and federally funded tribal clinics or provide information on “FQHC-look alikes,” organizations that meet the eligibility for PHS Section 330 grants, but which do not receive these funds; this lack of specificity does not affect the overall conclusions as all types of clinics are considered to be safety net facilities.

As of April 2011 Washington has 427 physicians waivered to offer BMT in their clinics. In contrast to national surveys from 2004 to 2008 (Arfken et al., 2010) in which 40% of waivered physicians were psychiatrists and 32% were in family or internal medicine, in Washington State 49.9% of waivered physicians were in family or internal medicine. Grouped together as primary care providers, they make up almost half of buprenorphine-waivered physicians in the state and are the plurality or majority in every geographic setting (47% of urban, 52% of large rural, 86% of small rural, and 100% of isolated rural providers).

The potential availability of treatment slots, i.e. the number of providers multiplied by the number of patients the physicians are waived to treat, is 18,760. These data suggest that in addition to the treatment of addiction in methadone clinics, a substantial proportion of addiction treatment can now take place in physicians' offices. Prior to the passage of DATA 2000, only 7 of Washington's 39 counties had ORT programs within their boundaries, while 26 had BMT programs in 2011. A number of studies have demonstrated that office-based BMT is efficacious and acceptable, and this study demonstrates that it has vastly broadened potential access, especially in rural areas (Sullivan, Chawarski, O'Connor, Schottenfeld, & Fiellin, 2005).

Primary care physicians are not alone in expanding access, as psychiatrists make up 29.5% of buprenorphine-waivered providers. Unlike primary care providers, however, psychiatrists are mainly located in urban and large rural areas. Since many patients with substance abuse have concomitant psychiatric problems (Nunes, Liu, Samet, Matseoane, & Hasin, 2006), the paucity of psychiatrists in rural areas creates an additional difficulty for the treatment of complex patients with dual diagnoses (Bohnert et al., 2011).

As one moves from urban to isolated rural areas, buprenorphine-waivered physicians, like their non-waivered peers, practice less often in private clinics and more often in publicly supported safety net settings. While this was our hypothesis, the degree to which it was true was surprising, and highlights the reliance of rural access to opioid treatment on a continuation of governmentally subsidized programs for the uninsured.

The knowledge that safety net settings are major employers of buprenorphine-waivered physicians in rural areas complicates the debate over treatment expansion. Rural safety nets already struggle with survival and staffing; more than one third of rural community health clinics have had a physician opening for more than 7months (Rosenblatt, Andrilla, Curtin, & Hart, 2006). One possible way to address this provider gap is to expand the use of this drug to mid-level practitioners, either through giving them the right to become waivered, or via supervision by remote physician prescribers.

If younger providers are truly under-represented, training of future medical graduates may be another way to expand treatment. Currently, however, there are only 31 waivered physicians working in Washington residency clinics, which means few mentors exist in these settings. Of note, 20 of the 31 physicians in residency clinics are at family medicine residencies. If these few are early indicators of future residency training, we may see the number of family medicine providers offering BMT continue to rise.

We speculate that in our rural areas the unmet need can be addressed in three ways: by increasing the number of providers eligible for waiver by conducting training programs, by increasing the number of waivered providers who actually go on to prescribe buprenorphine; and by encouraging active prescribers to increase their treatment slots from 30 to 100. However, it is not known which step will result in the largest increase in treatment slots. More work still needs to be done, especially documenting the impact of BMT in rural areas on individuals and communities, as well as assessing what helps rural physicians manage opioid dependent patients. National findings indicate that patients' financial barriers were the physicians' most common concern (Arfken et al., 2010). A study of residency programs and their use ofBMT would also help illuminate physician attitudes to the field of addiction medicine, and whether inclusion of buprenorphine in training would be an important way to create new cadres for treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Washington State Life Science Discovery Fund (WSU-LSDF subcontract number 109212-G002562). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding agency.

Footnotes

The role of the funder: The funder had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing of the report or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Disclosures: the following authors have no financial or personal relationships that may pose a conflict of interest: Roger Rosenblatt, Erik Kvamme, Mary Catlin, Caleb Banta-Green, and John Roll.

References

- Arfken CL, Johanson CE, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Expanding treatment capacity for opioid dependence with office-based treatment with buprenorphine: National surveys of physicians. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta-Green C. Opiate use and negative consequences in Washington state. University of Washington: Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Medicine. 2011;12:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Ilgen MA, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305:1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control, Prevention (CDC.) Unintentional drug poisoning in the United States, July 2010. [Retrieved November 22, 2011];2010 from. http://www.cdc.gov/homeandreseactionalSafety/pdf/poison-issue-brief.pdf.

- Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) US Department of Justice. Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (DEA ARCOS) [Retrieved April 24];Retail Drug Summary. 2007 from http://www.deadiversion.usdoj/gov/arcos/retail_drug_summary/index.html.

- DEA. US Department of Justice. DEA Registration Files, distributed by the Department of Commerce. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Doctorfinder. AMA doctor finder for patients. [Retrieved July–August];2011 http://extapps.ama-assn.org/doctorfinder/html/patient.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Poisoning and drug overdose. No: 530-090. [Retrieved 1 July 2011];2008 http://doh.wa.gov/hsqa/emstrauma/injury/pubs/icpg/DOH530090Poison.pdf.

- Lambert D, Gale J, Hartley D. Substance abuse by youth and young adults in rural America. The Journal of Rural Health. 2008;24:221. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner AI. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science. 1997;278:45–46. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes and of Health (NIH) Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. National consensus development panel on effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1936–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Liu X, Samet S, Matseoane K, Hasin D. Independent versus substance-induced major depressive disorder in substance-dependent patients: Observational study of course during follow-up. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1561–1567. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor PG. Methods of detoxification and their role in treating patients with opioid dependence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:961–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.961. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Curtin T, Hart LG. Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: Implications for planned expansion. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.9.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rural Health Research Center. RUCA Rural-urban commuting area codes. 2004 metropolitan and non-metropolitan population numbers and percentages by 4 RUCA 2.0 categories by state. [Retrieved July 6, 2011];2005 from http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca.

- Smart D. In: Physician characteristics and distribution in the US. Brockman C, Ryder M, editors. Chicago: AMA Publications and Clinical Solutions; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: Is it associated with new patients entering into treatment? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:113–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, et al. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine–naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence. A 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:1238–1246. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]