Abstract

IL-27 exerts pleiotropic suppressive effects on naïve and effector T cell populations during infection and inflammation. Surprisingly, however, the role of IL-27 in restricting or shaping effector CD4+ T cell chemotactic responses, as a mechanism to reduce T cell-dependent tissue inflammation, is unknown. In this study, using Plasmodium berghei NK65 as a model of a systemic, pro-inflammatory infection, we demonstrate that IL-27R signalling represses chemotaxis of infection-derived splenic CD4+ T cells in response to the CCR5 ligands, CCL4 and CCL5. Consistent with these observations, CCR5 was expressed on significantly higher frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from malaria-infected, IL-27R deficient (WSX-1−/−) mice than from infected wild type (WT) mice. We find that IL-27 signalling suppresses splenic CD4+ T cell CCR5-dependent chemotactic responses during infection by restricting CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cell sub-types, including Th1 cells, and also by controlling the overall composition of the CD4+ T cell compartment. Diminution of the Th1 response in infected WSX-1−/− mice in vivo by neutralisation of IL-12p40 attenuated CCR5 expression by infection-derived CD4+ T cells and also reduced splenic CD4+ T cell chemotaxis towards CCL4 and CCL5. These data reveal a previously unappreciated role for IL-27 in modulating CD4+ T cell chemotactic pathways during infection, which is related to its capacity to repress Th1 effector cell development. Thus, IL-27 appears to be a key cytokine that limits the CCR5-CCL4/CCL5 axis during inflammatory settings.

Introduction

IL-27 is a critically important and non-redundant regulator of pathogenic T cell responses during a variety of inflammatory conditions (1, 2). IL-27R (TCCR/WSX-1) deficient mice develop excessive pro-inflammatory T cell responses and resultant T cell-dependent immunopathology during a number of infections, including malaria, Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania major, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Trypanasoma cruzi infection (3-7). Whilst the molecular basis of IL-27 mediated suppression in vivo is still incompletely understood, IL-27 has been shown to attenuate Rorc expression, inhibiting Th17 cell responses, and to limit Th1 and Th2 responses (3, 4, 6-9). Moreover, IL-27 inhibits IL-2 production by effector CD4+ T cells and induces IL-10 production by naive, Tr1, Th1, Th2 and Th17-like cells (10-14).

Despite the number of studies examining the immunoregulatory effects of IL-27 on CD4+ T cells during infection, to date there has been no detailed investigation of whether IL-27 regulates CD4+ T cell trafficking and migration. This is surprising as excessive accumulation of CD4+ T cell populations in peripheral tissues, such as the liver, lung and brain, is a common pathological feature in infected IL-27R deficient mice (3, 6, 15, 16), indicating that CD4+ T cell migratory pathways may be dysregulated.

Chemokine receptor (CCR)-dependent pathways determine the migration patterns of effector T cells within tissues under both homeostatic and inflammatory conditions (17, 18). Chemokine receptors are heterogeneously displayed by naive and effector/memory T cell populations (17-21). For example, CCR7 is expressed on naive and memory T cell populations but is down-regulated on highly differentiated and migratory effector T cells (20). In contrast, many chemokine receptors, including CXCR3, CCR5, CCR6 and CXCR6, are predominantly expressed by effector T cells (19, 21). While it has been reported that different CD4+ T cell subsets (i.e. Th1, Th2, Th17, TFH and Treg) may express unique repertoires of chemokine receptors (22), it is becoming clear that, in vivo, T cell subset-restricted expression of individual chemokine receptors does not occur. Thus, CCR5, which has been described as a Th1 marker (23), has been shown to be expressed by IL-13-producing cells in the OVA-sensitised lung (24) and is now thought to be expressed on recently-activated cells of any subset (22).

A number of studies have examined the pathways that regulate chemokine receptor expression in CD4+ T cell populations. CD3 stimulation of T cell clones in vitro leads to up-regulation of CCR7, CCR8 and CXCR5 and down regulation of CCR1, CCR2, CCR3 and CCR5 (21). IFN-γ and TNF up-regulate CCR5 and CXCR3 on PBMCs (25, 26). In contrast, there is evidence that IL-10 down-regulates CCR5 expression (25) and IL-12 promotes or inhibits CCR5 expression depending on the experimental systems (27-29).

As IL-27 has a profound effect on T cell activation and on their production of IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-10 (3-16), we hypothesised that IL-27R signalling may also modulate the repertoire of chemokine receptor expression on effector CD4+ T cells during infection, and consequently regulate T cell chemotactic behaviour. Using Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection as a model systemic inflammatory condition, we show that abrogation of WSX-1 signalling elevates surface expression of CCR5 on CD4+ T cells during infection. Correspondingly, infection-derived WSX-1−/− effector CD4+ T cells displayed significantly enhanced migration to CCL4 and CCL5. Importantly, we show that upregulated expression of CCR5 on CD4+ T cells in WSX-1−/− mice during infection is not simply due to differences in the composition of the effector T cell pool in WSX-1−/− mice compared with WT mice, but is also due to specific alterations in CCR5 expression by individual T cell subsets. These data reveal an important role for IL-27R/WSX-1 in regulating CD4+ T cell chemotactic responses during inflammation.

Materials and methods

Mice and parasites

C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Harlan, UK. IL-27R deficient (WSX-1−/−) mice (30) were originally provided by Amgen Inc (Thousand Oaks, USA) and were bred at LSHTM and the University of Manchester. IL-10Rα deficient mice were provided by Professor Werner Muller, University of Manchester. All transgenic strains were fully back-crossed (N>10) to C57BL/6 mice. Animals were maintained under barrier conditions in individually ventilated cages. Cryopreserved P. berghei NK65 parasites were passaged once through C57BL/6 mice before being used to infect experimental animals. 6-10 week old mice were infected by intravenous injection of 104 parasitized red blood cells (pRBC). In some experiments, 250μg anti-IL-12 (C17.8) or anti-IL-2 (JES6-5H4), both from BioXCell Inc. (West Lebanon, USA), were injected i.p. every other day starting on day 7 post-infection.

Flow Cytometry

Spleens were removed from naïve and malaria-infected (day 7 or day 14 post infection (p.i.)) WT and WSX-1−/− mice. Single cell suspensions were prepared by homogenising through a 70μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (BD Biosciences). Absolute cell numbers were calculated by microscopy using a haemocytometer and live/dead cell identification was performed by trypan blue exclusion.

Phenotypic characterisation of CD4+ T cell populations was performed by surface staining with: anti-mouse CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-mouse CD44 (IM7), anti-mouse CD62L (MEL-14), anti-mouse KLRG1 (2F1), anti-mouse CCR1 (PA1-41062), anti-mouse CCR5 (7A4), anti-mouse CXCR3 (CXCR3-173), anti-mouse CXCR4 (2B11) and anti-mouse CXCR6 (221002), according to previously published protocols (3, 31). For intracellular staining, cells were first stained with antibodies to surface markers, washed and permeabilised by overnight incubation with the Foxp3 fixation/permeabilisation buffer (ebioscience). The cells were then washed and incubated for 30 minutes with anti-mouse T-bet (4B10), anti-mouse Gata3 (TWAJ) and anti-mouse Foxp3 (FJK-16s) and anti-chemokine receptor antibodies (above). All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, R & D systems or BD Biosciences.

All flow cytometry acquisition was performed using an LSR II (BD Systems, UK). All analysis was performed using Flowjo Software (Treestar Inc, OR, USA). Fluorescence minus one controls were utilised to validate flow cytometric data.

Transwell migration assays

Migration of purified CD4+ T cells was assessed by their movement through a 5μM pore transwell insert (Costar). Recombinant CCL4, CCL5, CCL20, CCL21, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL12, CXCL16 (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK or Peprotech, London, UK) all at 100ng/ml (optimal dose defined in titration experiments) were plated in the outer well of the transwell plate in a final volume of 600μl (RPMI 1640 + 5% FCS), before being incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for one hour. CD4+ T cells were purified by magnetic bead separation (Miltenyi Biotec) and 1×106 CD4+ T cells were then added to the inner well in a final volume of 100 μl (RPMI 1640 + 5% FCS). Purity of sorted cells was routinely >95%. The plate was incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for three hours and CD4+ T cell movement towards the recombinant chemokines was quantified by counting, by light microscopy, the number of cells that had migrated into the outer well. Directed movement toward chemokines was calculated by subtracting the number of cells that migrated in response to medium alone from the number that migrated in response to the individual chemokines.

Statistics

All data were tested for normal distributions using the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test. In two group comparisons, statistical significance was determined using the t test or the Mann–Whitney U test, depending on the distribution of the data. For three or more group comparisons, statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA, with the Tukey post hoc analysis for normally distributed data, or a Kruskal–Wallis test, with Dunn post hoc analysis for nonparametric data. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Differences were considered to be significantly different when p < 0.05.

Results

CD4+ T cells from WSX-1−/− malaria-infected mice demonstrate significantly enhanced chemotaxis towards CCL4 and CCL5

We and others have demonstrated an important role for IL-27R in limiting effector CD4+ T cell accumulation in non-lymphoid tissues during infection (3, 6, 15, 16). As the spleen is an important site for T cell priming, preceding cell migration during a variety of infections, including malaria (32), we hypothesised that WSX-1 signalling may directly suppress splenic CD4+ T cell chemotactic responses during inflammation. To test this, we isolated splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and malaria-infected (day 14 p.i) WT and WSX-1−/− mice and contrasted their chemotactic responses to a panel of chemokines in an in vitro transwell migration assay.

CD4+ T cells from naive WT and WSX-1−/− mice failed to migrate towards the majority of the tested chemokines, with the notable exceptions of CCL21 and CXCL12, towards which CD4+ T cells from naïve WT and WSX-1−/− mice migrated with equal efficiency (Figure 1A). These data demonstrate that there are no intrinsic differences in the chemotactic capacities of splenic CD4+ T cells in WT and WSX-1−/− mice under homeostatic conditions (Figure 1A). In contrast, splenic CD4+ T cells from infected (day 14 p.i.) WSX-1−/− mice displayed significantly increased chemotaxis to CCL4, CCL5 and, to a lesser extent, CXCL16 compared with CD4+ T cells from infected WT mice (Figure 1B). Interestingly, splenic CD4+ T cells from infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice displayed equivalent chemotactic responses to CCL20, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL12 (Figure 1B). These data show that lack of IL-27 signalling significantly affects chemotaxis of splenic CD4+ T cells towards specific chemokines during infection.

Figure 1. WSX-1 signalling restricts CD4+ T cell chemotactic responses during malaria infection.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. Splenic CD4+ T cells were purified from naïve and malaria-infected mice (D14 p.i.). (A,B), 1 ×106 purified (A) naïve, or (B) infection-derived, CD4+ T cells were placed in duplicate in the top chamber of a 5μm transwell and migration of cells towards recombinant chemokines (all at 100ng/ml) in the bottom chamber was assessed by microscopy. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group and are representative of 5 independent experiments. * P<0.05, WT vs WSX-1−/− mice.

WSX-1 restricts CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells during malaria infection

We hypothesised that the enhanced chemotaxis of splenic CD4+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice towards CCL4, CCL5 and CXCL16 was due to altered chemokine receptor expression by cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice. Consistent with our data showing that CD4+ T cells from naïve WT and WSX-1−/− display equivalent in vitro chemotactic responses, and also our previous observations that differences in CD4+ T cell function in WSX-1−/− mice manifest only after day 7 of malaria infection (3), there were no significant differences in chemokine receptor expression by splenic CD4+ T cells from naive WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 2A, B) or by cells obtained from WT and WSX-1−/− mice on day 7 p.i. (data not shown). However, CD4+ T cells obtained from WSX-1−/− mice on day 14 p.i. expressed significantly higher surface levels of CCR5 (the receptor for CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5), than did splenic CD4+ T cells from equivalent WT mice (Figure 2A, C). Splenic CD4+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice also displayed higher surface expression of CCR1 and CXCR6 compared with cells from infected WT mice, but the fold up-regulation in expression was significantly less than that observed for CCR5. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the surface expression of CXCR3 or CXCR4 by CD4+ T cells derived from infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 2C). Importantly, similar patterns of dysregulated chemokine receptor expression were observed when intracellular detection was performed (higher expression of CCR5 by CD4+ T cells derived from infected WSX-1−/− mice), showing that the differences in surface CCR5 expression were not simply the result of altered chemokine receptor recycling or internalisation (Figure 2D). Furthermore, CCR5 mRNA levels were higher in splenic CD4+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice than in cells from infected WT mice (results not shown).

Figure 2. SX-1 signalling restricts CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells during malaria infection.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. (A) Representative plots (gated on CD4+ T cells) showing the surface expression of chemokine receptors on splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice. (B, C) frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from (B) naïve and (C) malaria infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing chemokine receptors on the cell surface. (D) The frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from malaria infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing intracellular chemokine receptors. (E) The frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from malaria-infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and IL-10R−/− mice expressing chemokine receptors on the cell surface. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group with 3-5 mice per group. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B-D) * P<0.05, WT vs WSX-1−/− mice. (F) * P<0.05, WT vs IL-10R−/− mice.

WSX-1 and IL-10R signalling differentially control chemokine receptor expression by CD4+ T cells during malaria infection

It has been proposed that many of the immunoregulatory properties of IL-27 are directly related to its ability to promote IL-10 production by T cell subsets (11-14). Thus, we tested whether the altered repertoire of chemokine receptor expression by splenic CD4+ T cells from malaria-infected WSX-1−/− mice was phenocopied by CD4+ T cells from malaria-infected IL-10R−/− mice. Significantly higher frequencies of CD4+ T cells from malaria-infected IL-10R−/− mice expressed CCR5 compared with cells from infected WT mice (Figure 2E), but the fold increase in CCR5 expression was significantly lower than observed in WSX-1−/− mice (2.4 vs 4.3 respectively). Moreover, CCR1, CXCR3, CXCR4 and CXCR6 were expressed at equivalent levels by CD4+ T cells derived from infected WT and IL-10R−/− mice. These data demonstrate that IL-27R exerts stronger suppression of CCR5 expression than IL-10R in vivo during malaria infection. IL-27 may therefore synergize with/amplify the IL-10 signal to limit CCR5 expression.

WSX-1 signalling modulates both the magnitude and the cellular composition of the CD4+CCR5+ T cell population during malaria infection

Our results demonstrate that abrogation of IL-27R signalling primarily alters CCR5 expression by splenic CD4+ T cells during infection. To determine the mechanism by which WSX-1 signalling restricts CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells during infection, we first characterised the splenic CD4+CCR5+ T cell populations in WT and WSX-1−/− infected mice, to identify if the populations are comprised predominantly of a specific cellular subset in each strain of mice and/or whether the absence of WSX-1 also led to a consequential remodelling of the CD4+CCR5+ T cell compartment. Similar frequencies of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from naïve WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressed CD62L (naïve/central memory), CD44 (activated), GATA-3 (Th2), Foxp3 (Treg), T-bet (Th1) and KLRG-1 (terminal differentiation marker) (Figure 3A, B). Although similar frequencies of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from malaria-infected (d14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice also expressed CD44 and GATA-3, significantly fewer CD4+CCR5+ T cells from WSX-1−/− mice expressed CD62L and Foxp3 (Figure 3A, C). Moreover, compared to infected WT mice, a significantly higher proportion of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice expressed T-bet and KLRG-1 (Figure 3A, C). Indeed, approximately 60% of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from WSX-1−/− mice expressed T-bet (Figure 3A, C). As we have previously shown that the majority of CD4+ KLRG-1+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice co-express T-bet (Villegas-Mendez et al in press), our results indicate that a large proportion of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice are terminally differentiated Th1 cells.

Figure 3. Loss of WSX-1 signalling leads to remodelling of the CD4+CCR5+ T cell compartment and increased numbers of Th1-CCR5+ T cells during malaria infection.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. (A) Representative plots showing the surface expression of T cell markers on splenic CD4+ CCR5+ T cells from naïve and infectied (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice. (B, C) frequencies and (D, E) numbers of splenic CD4+CCR5+ T cells from (B, D) naïve and (C, E) malaria infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing the individual markers. (D, E) Numbers of cells calculated out of the 1×106 purified CD4+ T cells used in chemotaxis assays. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group with 3-5 mice per group and are representative of 4 independent experiments. * P<0.05, WT vs WSX-1−/− mice.

Using this phenotypic analysis, we calculated the numbers of CD4+CCR5+ T cells expressing the various T cell subset markers among 1 × 106 splenic CD4+ T cells, the number of CD4+ T cells used in the chemotaxis assays. Very few CD4+CCR5+ T cells were observed within 1×106 splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve WT or WSX-1−/− mice and there were no significant differences in the number of CD4+CCR5+ T cells expressing CD62L, CD44, Foxp3, T-bet, GATA-3 or KLRG-1 (Figure 3D). As expected, there were significantly increased numbers of CD4+CCR5+ T cells within the splenic CD4+ T cell population purified from infected WSX-1−/− mice compared with cells from infected WT mice (Figure 3E). Although there were no differences in the numbers of CD4+CCR5+ cells expressing CD62L, Gata-3 or Foxp3 in the CD4+ T cell populations from infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice, significantly increased numbers of CD4+CCR5+ cells co-expressing CD44, T-bet and KLRG-1 were present within the CD4+ T cell population from infected WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 3E). Similar results were obtained when calculating the total numbers of CD4+CCR5+ T cells expressing the subset markers within the spleens of naïve and infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice (results not shown).

Taken together, these data indicate that splenic CD4+CCR5+ T cell populations are broadly similar in naïve WT and WSX-1−/− mice, but that the composition of the population changes during the course of malaria infection in WSX-1−/− mice, leading to a significant increase in the frequencies and numbers of CD4+CCR5+ T cells displaying markers of terminally differentiated Th1 cells during malaria infection.

WSX-1 signalling represses CCR5 expression by all CD4+ T cell subpopulations during malaria infection

As the composition of the CD4+CCR5+ T cell population was significantly different in malaria-infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice, we examined whether this simply reflected global changes in the CD4+ T cell population within the spleen of malaria infected WSX-1−/− mice and/or whether WSX-1 specifically regulated chemokine receptor expression on individual CD4+ T cell sub-types, in particular Th1 cells. When compared with WT mice, significantly higher frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from WSX-1−/− mice expressed KLRG-1 and T-bet on day 14 of infection whereas the frequencies of other CD4+ T cell populations (naïve/central memory (CD62L+), Th2 (Gata3+) and Treg (Foxp3+)) did not differ between WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 4A). Consistent with this, significantly higher numbers of splenic CD4+ T cells derived from WSX-1−/− mice expressed KLRG-1 and T-bet compared with cells from WT mice (when calculated out of 1 ×106 purified CD4+ T cells used in the chemotaxis assays) (Figure 4B). Moreover, as the total number of splenic CD4+ T cells were comparable in malaria-infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice (results not shown), significantly higher numbers of CD4+T-bet+, CD4+KLRG-1+ T cells were observed in the spleens of malaria infected WSX-1−/− mice compared with infected WT mice (Figure 4C). There were no significant differences in the frequencies or numbers of any of the CD4+ T cell subsets within naïve WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 4A-C).

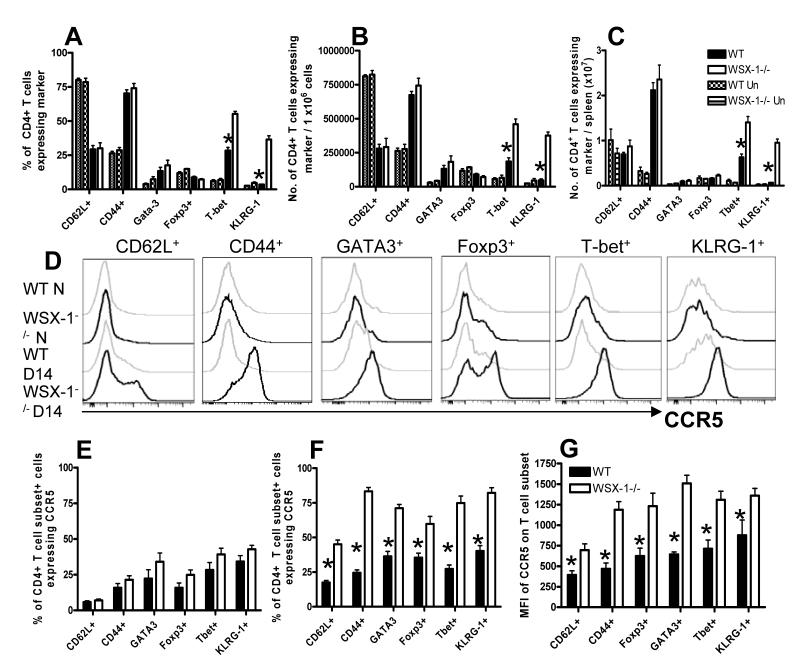

Figure 4. Loss of WSX-1 signalling modifies the structure of the CD4+ T cell population but also leads to unconstrained CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cell subsets during malaria infection.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. (A) Frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing the various T cell markers. (B, C) The numbers of CD4+ T cells derived from naïve and infection-derived (D14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing the various T cell subset markers out of (B) 1 ×106 CD4+ T cells utilised in the chemotaxis assay and (C) total splenocytes. (D) Representative histograms (gated on CD4+ Marker+ T cells) showing the surface expression of CCR5 on splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice. (E, F) frequencies and (G) MFI of CCR5 expression on (E) naïve and (F, G) malaria-infection derived (day 14 p.i.) splenic CD4+ Marker+ T cells. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group with 3-5 mice per group and are representative of 4 independent experiments. * P<0.05, WT vs WSX-1−/− mice.

Equivalent proportions of the CD4+ T cell subsets, as defined above, expressed CCR5 in naïve WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 4D, E). In contrast, there was a global increase in CCR5 expression by all examined CD4+ T cell subsets in infected WSX-1−/− mice compared with infected WT mice, as measured by both the frequency of subset+ cells expressing CCR5 and the mean fluorescence intensity of CCR5 expressed on subset+ cells on a cell-per-cell basis (Figure 4D, F, G). Thus, the increased expression of CCR5 by CD4+ T cells in malaria infected WSX-1−/− mice is not simply a consequence of skewing of T cell differentiation towards the Th1 phenotype; rather WSX-1 signalling seems to repress CCR5 expression in all CD4+ T cell subpopulations.

Blocking IL-12p40, but not IL-2, signalling attenuates Th1 polarisation and CCR5 expression in WSX-1−/− mice during malaria infection

Since the CD4+CCR5+ T cells accumulating in spleens of malaria-infected WSX-1−/− mice were mainly Th1 cells (Figure 3C), we hypothesised that attenuating the differentiation of Th1 cells would limit CCR5 expression thereby reducing CD4+ T cell chemotaxis to CCR5-ligands. Moreover, we expected that CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells derived from infected WSX-1−/− mice would correlate with IL-12Rβ1 and IL-2Rα (CD25) expression, as IL-12 and IL-2 signalling are required for the development and maintenance of Th1 cells (33). In partial agreement with this expectation, significantly higher frequencies of CD4+CCR5+ T cells from malaria-infected WSX-1−/− mice co-expressed IL-12Rβ1 compared with CD4+CCR5+ T cells from WT mice (Figure 5A-B) but CD25 expression did not differ on CD4+CCR5+ T cells from infected WT and WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 5A, C). These data suggested that IL-12R – but not IL-2 - may promote CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells (and, specifically, on Th1 cells) in WSX-1−/− mice during malaria infection.

Figure 5. Coordinated expression of CCR5 with IL-12R on CD4+ T cells derived from malaria-infected WSX-1−/− mice.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. (A) Representative plots (gated on CD4+ T cells) showing the surface expression of CCR5 versus IL-12Rβ1 and CD25 on splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice. (B-C) The frequencies of splenic CD4+CCR5+ T cells from naïve and malaria-infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing (B) IL-12Rβ1 and (C) CD25. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group with 3-5 mice per group and are representative of 2 independent experiments. * P<0.05, WT vs. WSX-1−/− mice.

Administration of anti-IL-12p40 mAb to WSX-1−/− mice (from day 7 of infection) significantly attenuated T-bet expression by splenic CD4+ T cells (Figure 6A, C) and concomitantly reduced the frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells that expressed CCR5 (Figure 6B, D). Anti-IL-12p40 also slightly reduced CCR1 expression by splenic CD4+ T cells in WSX-1−/− mice (results not shown). In contrast, anti-IL-2 mAb treatment had no affect on the frequencies of splenic CD4+T–bet+ or CD4+CCR5+ cells in infected WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 6A-D). Interestingly, neither anti-IL-12p40 nor anti-IL-2 treatment led to changes in CCR5 expression by other CD4+ T cell subsets (results not shown). As expected, anti-IL-12p40 mAb administration to WSX-1−/− mice led to a reduction in the numbers of total CD4+CCR5+ T cells and CD4+CCR5+ cells expressing CD44, T-bet and KLRG-1 as calculated within 1×106 purified CD4+ T cells used in chemotaxis assays (Figure 6E), and total splenocytes (results not shown). Anti-IL-12p40 treatment to WSX-1−/− mice did not, however, alter the numbers of CD4+CCR5+ cells co-expressing CD62L, Foxp3 or GATA-3 (Figure 6E and results not shown). Together these data demonstrate that IL-12, but not IL-2, is required for the differentiation of splenic CD4+CCR5+ Th1 cells in malaria-infected WSX-1−/− mice. Consistent with this, CD4+ T cells from anti-IL-12p40 treated infected WSX-1−/− mice displayed significantly reduced chemotaxis to CCL4 and CCL5, whereas chemotaxis of CD4+ T cells from anti-IL-2 treated mice was similar to that of cells from control (untreated) infected WSX-1−/− mice (Figure 6F and results not shown).

Figure 6. Anti-IL-12p40 mAb administration to malaria infected WSX-1−/− mice inhibits T-bet expression, reverses CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells and attenuates CD4+ T cell chemotaxis.

WT and WSX-1−/− mice were infected with 104 P. berghei NK65 pRBCs. Some WSX-1−/− mice were treated with 250μg anti-IL-12p40 or anti-IL-2 mAbs every 2nd day starting on day 7 p.i. (A, B) Representative plots (gated on CD4+ T cells) showing the surface expression of (A) T-bet and (B) CCR5 on splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve and infected (day 14 p.i.) WT and WSX-1−/− mice and WSX-1−/− mice treated with anti-IL-12p40 or anti-IL-2. (C, D) The frequencies of splenic CD4+ T cells from naïve, infected control and infected antibody-treated WT and WSX-1−/− mice expressing (C) T-bet or (D) CCR5. (E) The numbers of CD4+ T cells from WT, anti-IL-12p40 mAb treated and control infected WSX-1−/− mice expressing the various T cell subset markers out of 1 ×106 CD4+ T cells utilised in the chemotaxis assay (F) 1×106 purified CD4+ T cells from infected WT, WSX-1−/− and WSX-1−/− mice treated with anti-IL-12p40 or anti-IL-2 were placed in duplicate in the top chamber of a 5μm transwell and migration towards recombinant CCL4 (100ng/ml) in the bottom chamber was assessed by microscopy. Data are the mean +/− SEM of the group with 3-5 mice per group and are representative of 2 independent experiments. * P<0.05, WT vs WSX-1−/− control mice, ~ P<0.05, WT vs anti-IL-12p40 treated WSX-1−/− mice, + P<0.05, WT vs anti-IL-2 treated WSX-1−/− mice, † P<0.05, WSX-1−/− control mice vs. anti-IL-12p40 treated WSX-1−/− mice, ‡ P<0.05, anti-IL-12p40 treated WSX-1−/− mice vs. anti-IL-2 treated WSX-1−/− mice.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that IL-27 signalling via WSX-1 modulates the chemokine receptor repertoire expressed by activated CD4+ T cells during malaria infection. In particular, we have shown that IL-27 is an important regulator of the CCR5-CCL4/CCL5 pathway, revealing an entirely novel pathway by which IL-27 can limit CD4+ T cell accumulation in tissues. This observation is likely to have major relevance for a number of inflammatory conditions where WSX-1 is known to suppress T cell-mediated inflammation (Reviewed 1, 2).

Remodelling of the CD4+ T cell compartment, in particular enhanced Th1 polarisation, was not the sole reason for increased CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells in infected WSX-1−/− mice. Indeed, our data show that signalling via WSX-1 also suppresses CCR5 expression on CD62L+, T-bet+, GATA-3+ and Foxp3+ CD4+ T cell populations. As CD62L, GATA-3 and Foxp3 expression broadly segregates from T-bet on day 14 of infection (results not shown), we conclude that, in an inflammatory environment, WSX-1 signalling represses expression of CCR5 on most, if not all, CD4+ T cell populations, independent of their polarisation or activation status. Thus, IL-27/WSX-1 signalling may be a critical regulator of T cell CCR5 expression during infection, non-specifically limiting accumulation of effector cells in affected tissues and dampening inflammation. Interestingly, it has very recently been shown that IL-27 directs the development of Th1 adapted CXCR3+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells during T. gondii infection, (34), further supporting the important role for IL-27 in controlling chemokine receptor expression by T cells during infection.

We found that, in the malaria model, the enhanced chemotactic response of splenic CD4+ T cells is dominantly driven by Th1 cells. Specific inhibition of Th1 CCR5+ cell development, and potentially function, in infected WSX-1−/− mice by treatment with anti-IL-12p40 mAbs led to a major reduction in infection-derived CD4+ T cell chemotaxis towards CCL4 and CCL5 in vitro. Interestingly, anti-IL-12p40 mAb treatment of infected WSX-1−/− mice reduced CD4+ T cell chemotaxis to WT levels but failed to induce the complete downregulation of CCR5 expression. CCR5 mediated chemotaxis requires integrated signalling through a number of intracellular pathways, including Pi3K, JAK/STAT and Map Kinase pathways (35). Thus our results suggest that anti-IL-12p40 mAb treatment may also negatively affect the efficiency of CCR5 signal transduction in CD4+ T cells, attenuating the functionality of the remaining CCR5 molecules expressed on the cell surface. Of relevance, IL-12 has been shown to activate Pi3K, thus potentially linking IL-12R and CCR5 signalling events (36). Consequently, our data suggest that IL-27R signalling normally limits splenic CD4+ T cell chemotaxis during malaria infection by coordinately inhibiting Th1 cell differentiation and suppressing CCR5 expression and intracellular signalling pathways. Although we predict that Th1 cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice would show enhanced migratory capacity when compared to Th1 cells from WT mice, due to their higher CCR5 expression, we cannot directly test this prediction due to the lack of reliable surface markers for purification of splenic Th1 cells from infected mice (IL-18R and CD226 are good markers of Th1 cells in WSX-1−/− mice but not WT mice, (Villegas-Mendez unpublished observations). Of note, enhanced accumulation of CCR5 bearing CD4+ T cells in the spleen of WSX-1−/− mice during malaria infection was not simply due to elevated retention of these cells in the spleen of WSX-1−/− mice versus WT mice and migration of CD4+CCR5+ T cells into non-lymphoid organs is increased in WSX-1−/− mice during infection (3 and Findlay et al manuscript in preparation).

The mechanism(s) by which IL-27R signalling modulates CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells during infection is not clear. We do not believe that this simply reflects changes in the extent or rate of CCR5 internalisation, or (re)cycling between the cell membrane and the intracellular environment, as intracellular staining for CCR5 gave very similar results to those obtained by surface staining. Moreover, the increased MFI of CCR5 expression on the analysed CD4+ T cell subsets shows that more CCR5 is present on CD4+ T cells derived from infected WSX-1−/− mice on a cell-per-cell basis. Although CCR5 mRNA transcript levels are higher in CD4+ T cells from infected WSX-1−/− mice than infected WT mice, indicating that IL-27 may regulate CCR5 through transcriptional repression and/or by reducing mRNA stability, the heterogeneity of the analysed material, with an increased proportion of Th1 cells in the CD4+ T cell population from WSX-1−/− mice, complicates the interpretation of this experiment. Of interest, however, miRNA mimics can suppress CCR5 expression on leukocytes in vitro (37) indicating that CCR5 expression is closely linked to mRNA transcription and/or translation. Whether IL-27 modulates expression of microRNAs that target the 3′UTR of CCR5 transcripts has yet to be examined.

Our data clearly shows that IL-12p40 plays an important role in promoting CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells in WSX-1−/− mice during malaria infection. IL-12 has previously been shown to promote CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells (28, 29). IL-12p70 production is significantly elevated in WSX-1−/− mice during malaria infection (3) and treatment with anti-IL-12p40 significantly reduced CCR5 expression, at least in part due to reduction in Th1 cell polarisation. Recent work in our laboratory suggests that IL-27 limits the magnitude of the Th1 cell response, and Th1 cell terminal differentiation, during malaria infection by inhibiting Th1 cell responsiveness to IL-12p70, which appears to cause instability in the Th1 molecular programme, rather than affecting T cell proliferation or apoptosis (Villegas-Mendez et al in press). Of note, however, whilst anti-IL-12p40 treatment of WSX-1−/− mice reduced T-bet expression to WT levels, CCR5 expression, although significantly diminished, was still significantly higher than in WT mice. Thus, we believe our results indicate that other additional signals may act independently from IL-12p40 to promote CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cell subsets in infected WSX-1−/− mice. Alternatively, IL-27R ligation may directly limit CCR5 expression through STAT signalling pathways (38),

Interestingly, the redox status of leukocytes strongly determines CCR5 stability and expression; reactive oxygen species promote CCR5 expression whereas anti-oxidants inhibit CCR5 expression (39). WSX-1 is known to suppress ROS production by human neutrophils (40). Thus, it is possible that increased IL-12 and IFN-γ production, coupled with loss of direct WSX-1-mediated inhibition of ROS production, in WSX-1−/− mice during malaria leads to enhanced ROS generation, which then non-specifically promotes CCR5 expression on various CD4+ T cell populations. Nevertheless, we do not believe that WSX-1 regulates CCR5 expression on CD4+ T cells simply and specifically through IL-10 dependent mechanisms as CCR5 expression is less affected in IL-10R−/− mice during malaria infection than in WSX-1−/− mice.

In summary, we have identified an important and previously unappreciated role for IL-27R in regulating chemokine receptor pathways that control CD4+ T cell chemotactic responses. In particular we have defined a critical role for IL-27R in suppressing CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cell populations during infection. Our results may have significant implications for understanding how IL-27/WSX-1 regulates CD4+ T cell migration and tissue accumulation in a variety of inflammatory conditions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lisa Grady, The University of Manchester, for technical support.

Grant Support The study was supported by the BBSRC (004161 and 020950) and by a Medical Research Council Career Development Award to KNC (G0900487).

References

- 1.Yoshida H, Nakaya M, Miyazaki Y. Interleukin 27: a double-edged sword for offense and defense. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1295–303. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall AO, Silver JS, Hunter CA. The immunobiology of IL-27. Adv Immunol. 2012;115:1–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394299-9.00001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findlay EG, Greig R, Stumhofer JS, Hafalla JC, de Souza JB, Saris CJ, Hunter CA, Riley EM, Couper KN. Essential role for IL-27 receptor signaling in prevention of Th1-mediated immunopathology during malaria infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:2482–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villarino A, Hibbert L, Lieberman L, Wilson E, Mak T, Yoshida H, Kastelein RA, Saris C, Hunter CA. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity. 2003;19:645–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamano S, Himeno K, Miyazaki Y, Ishii K, Yamanaka A, Takeda A, Zhang M, Hisaeda H, Mak TW, Yoshimura A, Yoshida H. WSX-1 is required for resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection by regulation of proinflammatory cytokine production. Immunity. 2003;19:657–67. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holscher C, Holscher A, Ruckerl D, Yoshimoto T, Yoshida H, Mak T, Saris C, Ehlers S. The IL-27 receptor chain WSX-1 differentially regulates antibacterial immunity and survival during experimental tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:3534–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artis D, Villarino A, Silverman M, He W, Thornton EM, Mu S, Summer S, Covey TM, Huang E, Yoshida H, Koretzky G, Goldschmidt M, Wu GD, de Sauvage F, Miller HR, Saris CJ, Scott P, Hunter CA. The IL-27 receptor (WSX-1) is an inhibitor of innate and adaptive elements of type 2 immunity. J Immunol. 2004;173:5626–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diveu C, McGeachy MJ, Boniface K, Stumhofer JS, Sathe M, Joyce-Shaikh B, Chen Y, Tato CM, McClanahan TK, de Waal Malefyt R, Hunter CA, Cua DJ, Kastelein RA. IL-27 blocks RORc expression to inhibit lineage commitment of Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5748–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas S, Ghilardi N, Li J, de Sauvage FJ. IL-27 regulates IL-12 responsiveness of naive CD4+ T cells through Stat1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15047–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536517100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villarino AV, Stumhofer JS, Saris CJ, Kastelein RA, de Sauvage FJ, Hunter CA. IL-27 limits IL-2 production during Th1 differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:237–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awasthi A, Carrier Y, Peron JP, Bettelli E, Kamanaka M, Flavell RA, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Weiner HL. A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1380–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, Ernst M, Saris CJ, O’Shea JJ, Hunter CA. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pot C, Jin H, Awasthi A, Liu SM, Lai CY, Madan R, Sharpe AH, Karp CL, Miaw SC, Ho IC, Kuchroo VK. Cutting edge: IL-27 induces the transcription factor c-Maf, cytokine IL-21, and the costimulatory receptor ICOS that coordinately act together to promote differentiation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:797–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freitas do Rosario AP, Lamb T, Spence P, Stephens R, Lang A, Roers A, Muller W, O’Garra A, Langhorne J. IL-27 promotes IL-10 production by effector Th1 CD4+ T cells: a critical mechanism for protection from severe immunopathology during malaria infection. J Immunol. 2012;188:1178–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosas LE, Satoskar AA, Roth KM, Keiser TL, Barbi J, Hunter C, de Sauvage FJ, Satoskar AR. Interleukin-27R (WSX-1/T-cell cytokine receptor) gene-deficient mice display enhanced resistance to leishmania donovani infection but develop severe liver immunopathology. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:158–69. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stumhofer JS, Laurence A, Wilson EH, Huang E, Tato CM, Johnson LM, Villarino AV, Huang Q, Yoshimura A, Sehy D, Saris CJ, O’Shea JJ, Hennighausen L, Ernst M, Hunter CA. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:937–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sallusto F, Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:949–52. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Mackay CR. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in T-cell priming and Th1/Th2-mediated responses. Immunol Today. 1998;19:568–74. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roman E, Miller E, Harmsen A, Wiley J, Von Andrian UH, Huston G, Swain SL. CD4 effector T cell subsets in the response to influenza: heterogeneity, migration, and function. J Exp Med. 2002;196:957–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallusto F, Kremmer E, Palermo B, Hoy A, Ponath P, Qin S, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Switch in chemokine receptor expression upon TCR stimulation reveals novel homing potential for recently activated T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2037–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<2037::AID-IMMU2037>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bromley SK, Mempel TR, Luster AD. Orchestrating the orchestrators: chemokines in control of T cell traffic. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:970–80. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loetscher P, Uguccioni M, Bordoli L, Baggiolini M, Moser B, Chizzolini C, Dayer JM. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:344–5. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto A, Takatsuka S, Ishida I, Chiba J. Production of human antibodies to native cytokine receptors using the genetic immunization of KM mice. Hum Antibodies. 2009;18:75–80. doi: 10.3233/HAB-2009-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson BK, Czerniewski M, Andersson J, Sullivan Y, Su F, Jiyamapa D, Burki Z, Landay A. Regulation of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression by type 1 and type 2 cytokines: CCR5 expression is downregulated by IL-10 in CD4-positive lymphocytes. Clin Immunol. 1999;91:254–62. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima C, Mukai T, Yamaguchi N, Morimoto Y, Park WR, Iwasaki M, Gao P, Ono S, Fujiwara H, Hamaoka T. Induction of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on TCR-stimulated T cells: dependence on the release from persistent TCR-triggering and requirement for IFN-gamma stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1792–801. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200206)32:6<1792::AID-IMMU1792>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Losana G, Bovolenta C, Rigamonti L, Borghi I, Altare F, Jouanguy E, Forni G, Casanova JL, Sherry B, Mengozzi M, Trinchieri G, Poli G, Gerosa F, Novelli F. IFN-gamma and IL-12 differentially regulate CC-chemokine secretion and CCR5 expression in human T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:735–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Niessner A, Nakajima T, Ma-Krupa W, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Interleukin 12 induces T-cell recruitment into the atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2006;98:524–31. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204452.46568.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwasaki M, Mukai T, Nakajima C, Yang YF, Gao P, Yamaguchi N, Tomura M, Fujiwara H, Hamaoka T. A mandatory role for STAT4 in IL-12 induction of mouse T cell CCR5. J Immunol. 2001;167:6877–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida H, Hamano S, Senaldi G, Covey T, Faggioni R, Mu S, Xia M, Wakeham AC, Nishina H, Potter J, Saris CJ, Mak TW. WSX-1 is required for the initiation of Th1 responses and resistance to L. major infection. Immunity. 2001;15:569–78. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villegas-Mendez A, de Souza JB, Murungi L, Hafalla JC, Shaw TN, Greig R, Riley EM, Couper KN. Heterogeneous and tissue-specific regulation of effector T cell responses by IFN-gamma during Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:2885–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Portillo HA, Ferrer M, Brugat T, Martin-Jaular L, Langhorne J, Lacerda MV. The role of the spleen in malaria. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:343–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275–83. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall AO, Beiting DP, Tato C, John B, Oldenhove G, Pritchard G. Harms, Lombana C. Gonzalez, Silver JS, Bouladoux N, Grainger J, Wojno E.D. Tait, Stumhofer JS, Harris TH, Wagage S, Roos DS, Scott P, Turka LA, Cherry S, Reiner SL, Cua D, Belkaid Y, Elloso MM, Hunter CA. Distinct roles for IL-27 and IFN-γ in the development of T-bet+ Treg required to limit infection-induced pathology. Immunity. 2012;37:511–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong MM, Fish EN. Chemokines: attractive mediators of the immune response. Semin Immunol. 2003;15:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo JK, Cho JH, Lee SW, Sung YC. IL-12 provides proliferation and survival signals to murine CD4+ T cells through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2002;169:3637–3643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehsani A, Saetrom P, Zhang J, Alluin J, Li H, Snove O, Jr., Aagaard L, Rossi JJ. Rational design of micro-RNA-like bifunctional siRNAs targeting HIV and the HIV coreceptor CCR5. Mol Ther. 2010;18:796–802. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SH, Gunst KV, Sarvetnick N. STAT4/6-dependent differential regulation of chemokine receptors. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saccani A, Saccani S, Orlando S, Sironi M, Bernasconi S, Ghezzi P, Mantovani A, Sica A. Redox regulation of chemokine receptor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2761–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li JP, Wu H, Xing W, Yang SG, Lu SH, Du WT, Yu JX, Chen F, Zhang L, Han ZC. Interleukin-27 as a negative regulator of human neutrophil function. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:284–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]