Abstract

Non-adherence as a major contributor to poor treatment outcomes. This study aimed to explore the effectiveness of existing interventions promoting adherence to antimalarial drugs by systematic review. The following databases were used to identify potential articles: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane CENTRAL, and CINAHL (through March 2013). From 1,813 potential papers identified, 16 studies met the selection criteria comprising 9,247 patients. Interventions were classified as packaging aids, visual media, combined visual media and verbal information, community education, medication supervision, and convenient regimen. These interventions were shown to increase adherence to antimalarial drugs (median relative risk = 1.4, interquartile range 1.2–2.0). Although a most effective intervention did not emerge, community education and visual media/verbal information combinations may well have most potential to improve adherence to antimalarial medication. These interventions should be implemented in combination to optimize their beneficial effects. The current understanding on improved adherence would facilitate to contain outbreaks of malaria cost effectively.

Introduction

Malaria is a major public health problem in tropical countries with 300 to 500 million clinical cases globally, thus imposing an economic burden, particularly in countries with high transmission rates.1,2 The effective control and treatment of malaria remains a challenge and the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested that rapid treatment with antimalarials is necessary.3 Ample evidence has shown that adherence is one of the most important factors that contributes to controlling outbreaks of the disease.3–5 Poor adherence jeopardizes antimalarial effectiveness and control of malarial transmission.

Current evidence suggests that poor to moderate adherence is common in malarial treatment in the community6–9; an effective approach is therefore essential to address this problem. To date, several interventions aiming to promote adherence have been developed and implemented in endemic areas where poor adherence was observed. Understanding the relative effectiveness of each type of intervention could thus help to formulate clear guidelines that improve adherence to medication. A previous systematic review had tried to illustrate such information and found that interventions focusing on carers, behavior, user-friendly packaging, and provision of correct dosage improved adherence to antimalarial drugs.10 Although this review gave an inclusive outline of the available effective interventions, it was dated back in 2005 and did not adequately provide an overview of the quality of the included studies. Furthermore, designs of the studies included in the previous review were varied and not limited to intervention studies. Considering the previous shortcomings and the growing number of published literature, an update focusing on the current evidence for the role of interventions that promote adherence to antimalarial drugs is needed. This will provide an informative review for healthcare practitioners and policymakers to deliver effective antimalarial treatment using efficacious interventions. To this end, we aimed to explore the relative effectiveness of existing interventions to improve antimalarial drug adherence.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Cochrane Collaboration framework and the reporting followed the PRISMA Statement.11,12

Search strategy.

The following bibliographic databases were systematically searched since their inception dates to March 2013: MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane CENTRAL. The search terms: antimalarial, compliance or adherence, and malaria were used. Authors of the potential papers were contacted where necessary to clarify missing or incomplete data. We identified all relevant studies regardless of language.

Study selection.

Full papers of potentially relevant studies were checked for eligibility to the inclusion criteria by three authors (AF, TD, and CK). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Inclusion criteria.

Original comparative studies investigating the effectiveness of any intervention that aimed to improve adherence to antimalarial drugs were included in this review if they were conducted on outpatients with uncomplicated malaria and provided sufficient data for calculating the rate of adherence to antimalarial drugs.

Data extraction.

The participants, study design, type of intervention, adherence rates to antimalarial drugs, and cure rates for each type of intervention were extracted by two reviewers (TD, AF). Rates of adherence and clinical efficacy were presented as number of patients on an intention to treat basis.

Assessment of study quality.

We assessed risk of bias in studies using a standard method, the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Studies.13 The following six domains were assessed: 1) random sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding of patients, personnel, and outcome assessors, 4) missing data, 5) lack of bias or elective outcome reporting, and 6) other sources of bias. A Jadad score was also applied to assess the methodological quality of controlled clinical trials.14

Outcome measures and analytical strategy.

The primary outcome was the prevalence of adherence, calculated by the number of patients who adhered to antimalarial drugs and divided by the total number of patients prescribed antimalarial drugs. We performed the calculation of adherence rate for all intervention types (i.e., packaging aids, visual media, combined approach of visual media and verbal information, community education, medication supervision and convenient regimen). Sensitivity analysis examined the impact of promoting interventions on adherence rate. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method was performed to test for heterogeneity15 and P < 0.10 was considered evidence of heterogeneity15,16; the degree of between-study heterogeneity was assessed using χ2 and I2 tests to determine whether it was appropriate to compute a meta-analytic summary estimate. An I2 of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicates low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively15; if there was a significant heterogeneity between studies, the results across these studies were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR). The software used to perform all statistical analyses was STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Search results.

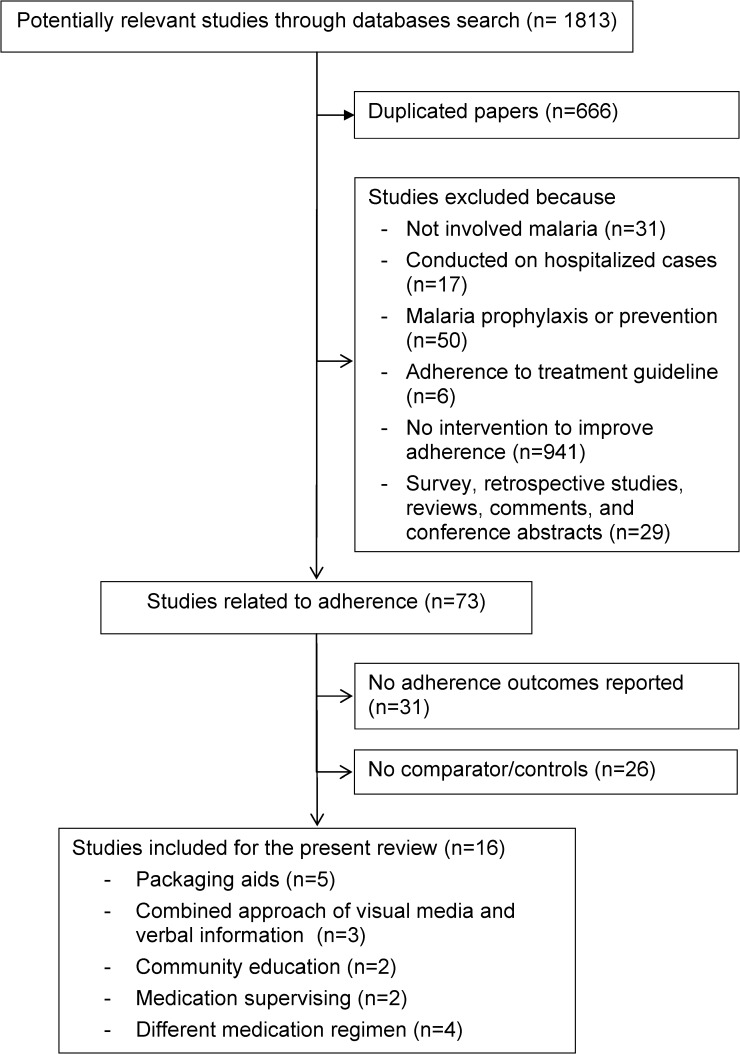

Out of the 1,813 potential articles, 16 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Figure 1)17–32 and comprised a total of 9,247 patients. Of these, two studies included two different interventions.18,22 Studies were published from 1998 to 2011. Ten studies (62.5%) were undertaken in Africa20–26,29,31,32 and the remainder were set in Asia.17–19,27,28,30 All the studies were based in the public healthcare sectors (12 in a hospital17,19–22,24–31 and 4 in a community setting)18,23,25,32 but one study also included a group from the private sector.32 Eight studies (50.0%) investigated the impact of adherence promoting intervention on children or their mothers/caregivers.20,22,23,25,26,29,31,32 The other studies enrolled adults or patients at all ages.17–19,21,24,27,28,30 In 14 studies (87.5%), the patients were infected with falciparum malaria18–29,31,32 and the remaining studies used patients with vivax malaria.17,30 Six studies (37.5%) used chloroquine,20–25 five studies (31.2%) used artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT).26,28,29,31,32 Other antimalarials were artemisinin monotherapy,19 sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine,29 quinine,26 quinine plus tetracycline,18,19 chloroquine plus sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine,27 and chlorproguanil-dapsone.31 The therapeutic regimens for both studies on vivax malaria were chloroquine followed by primaquine.17,30

Figure 1.

Flow of the included studies.

The majority of studies (13 studies; 81.3%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs).17,19–23,26–32 Twelve studies (75.0%)19–24,26–30,32 provided a definition of adherence (as defined in Table 1) although these definitions and the methods used to assess adherence varied between studies. Remaining drug count was the main technique used to assess adherence.18–26,28,29,31 The other methods used were interview,18–21,25,27,30–32 questionnaire or self-report,6,17,21–24,26,28 and drug concentration monitoring.17

Table 1.

Study and demographic characteristics of the included studies

| Studies | Study designs (country) | Number of patients | Type of malaria and antimalarial drug | Interventions | Duration of treatment | Treatment outcomes | Method to assess adherence | Definition of adherence | Adherence results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Packaging aids | |||||||||

| Lauwo, 200627 | RCT (Papua New Guinea) | 285 patients (PP group: 129, NPP group: 156) | Falciparum malaria CQ 3 days + SP single dose | Prepackaging | 3 days | Cure rate PP: 59.7% (77/129) NPP: 59.6% (93/156) | Interview | Patients' ability to remember instruction and to complete the medication as prescribed or directed | PP group: 66.7% (86/129) NPP group: 58.3% (91/156) |

| Afenyadu, 200525 | Quasi-experimental (Ghana) | 168 primary school pupils (PP group: 114, NPP group: 54) | Falciparum malaria CQ | Prepackaging | 3 days | NS | Remaining drug count and parents or guardians interview | NS | PP group: 88.5% (100/114) NPP group: 88.9% (48/54) |

| Ansah, 200120 | RCT (Ghana) | 299 children (PP tablets: 155, syrup: 144) | Falciparum malaria CQ | Prepackaging | 3 days | Cure rate PP: 92.9% (144/155) Syrup: 95.1% (137/144) | Remaining drug count (standard graded measuring syringe) and caregiver interview | Relation to dosage, frequency of daily administration and duration of treatment | PP tablets: 91.0% (141/155) Syrup: 42.4% (61/144)** |

| Yeboah, 200121 | RCT (Ghana) | 654 patients (PP group: 314, NPP group: 340) | Falciparum malaria CQ | Prepackaging | 3 days | NS | Remaining drug count, questionnaire, and interview | Taking medication on all 3 intervening days | PP group: 72.1% (189/262) NPP group: 49.8% (123/247)** |

| Qingjun, 199817 | RCT (China) | Phase I: 324 patients (PP group: 161, NPP group: 163) | Vivax malaria CQ and PQ | Blister pack | CQ: 3 days + PQ: 8 days | NS | Self-report | NS | PP group: 96.9% (156/161) NPP group: 82.8% (135/163)** |

| Phase II: 246 patients (PP group: 138, NPP group 134) | Vivax malaria CQ and PQ | Blister pack | CQ: 3 days + PQ: 8 days | NS | Drug concentration measurement | NS | PP group: 97.1% (134/138) NPP group: 80.5% (108/134)** | ||

| (2) Visual media | |||||||||

| Okonkwo, 200122 | RCT (Nigeria) | 415 children aged 0.5–5 years (Intervention: 225, control: 190) | Falciparum malaria CQ | pictorial insert | 3 days | Improved clinical state§ Intervention: 89.8% (202/225) Control 93.7% (178/190) | Remaining drug count and questionnaire | Full compliance: answers to the questionnaire and expected amount left in the bottle | Intervention: 52.0% (117/225)† Control: 36.5% (69/190)†** |

| (3) Combined approach of visual media and verbal information | |||||||||

| Agyepong, 200224 | Quasi-experiment (Ghana) | 221 clients (Intervention: 130, control: 91) | Falciparum malaria CQ | Information provision and drug labeling | 3 days | NS | Remaining drug count and self-report | Minimum daily adherence: taking at least the minimum prescribed doses every day for 3 day | Intervention: 72.3% (94/130) Control: 52.7% (48/91)** |

| Okonkwo, 200122 | RCT (Nigeria) | 407 children aged 0.5–5 years (Intervention: 217, control: 190) | Falciparum malaria CQ | pictorial insert + verbal instruction | 3 days | Improved clinical state§ Intervention: 96.8% (210/217) Control: 93.7% (178/190) | Remaining drug count and questionnaire | Full compliance: answers to the questionnaire and expected amount left in the bottle | Intervention: 73.3% (159/217)† Control: 36.5% (69/190)†** |

| (4) Community education | |||||||||

| Kangwana, 201132 | RCT (Kenya) | 2,749children aged 3–59 months (Children who received AM-L: Intervention: 729, control: 356) | Falciparum malaria AM-L | Training of retail outlet staff, and community awareness activities | 3 days | NS | Interview | Reporting consumption of exactly the correct number of tablets within 3 days of receiving medication. | Intervention: 66.5% (488/729) Control: 49.4 (176/356)** |

| Winch, 200323 | RCT (Mali) | 286 children 1 to 72 months (intervention: 152, controls: 134) | Falciparum malaria CQ | Visual aid and verbal instruction via village drug kit manager | 3 days | NS | Remaining drug count and questionnaire | Recommended by National IMCI program of Ministry of Health of Mali | Intervention: 71.7% (109/151) Control: 21.6% (29/134)** |

| Denis, 199818 | Prospective study (Cambodia) | 672 patients | Falciparum malaria Q + TT | Video and poster | 7 days | NS | Interview and remaining drug count | NS | Pre-intervention: 0.5% (1/204) Post-intervention: 20.4% (33/162)** |

| Poster | 7 days | NS | Interview and remaining drug count | NS | Pre-intervention: 5.6% (8/143) Post-intervention: 12.3% (18/163) | ||||

| (5) Medication supervision | |||||||||

| Rahman, 200828 | RCT (Bangladesh) | 320 patients (DOT: 160, NDOT: 160) | Falciparum malaria AM-L | DOT | 3 days | ACPR by day 42 DOT: 83.8% (134/160) non-DOT: 81.9% (131/160) | Remaining drug count and questionnaire | No tablets remained or reported inadequate intake of dose and/or time of tablets | DOT: 100% (160/160)‡ non-DOT: 93.1% (149/160)** |

| Takeuchi, 201030 | RCT (Thailand) | 216 patients (DOT: 109, SAT: 107) | Vivax malaria CQ plus PQ | DOT | 14 days | Reappearance rate at days 90 DOT: 2.8% (3/109) non-DOT: 11.2% (12/107) | Interview | No missing a single dose | DOT¶: 100% (109/109) non-DOT: 80.4% (86/107)** |

| (6) Convenient regimen | |||||||||

| Dunyo, 201131 | RCT (Gambia) | 1,238 children (CD: 620, AM-L: 618) | Falciparum malaria CD (3 doses) or AM-L (5 doses) | Once daily of CD or twice daily of AM-L (blister packs) | 3 days | Clinical failure by day 28: CD: 17.6% (109/620) AM-L: 5.8% (36/618) | Remaining drug count and interview | NS | CD: 90.6% (562/620) AM-L: 65.0% (402/618)** |

| Faucher, 200929 | RCT (Benin) | 192 children (AM-L: 96, ASAQ: 96) | Falciparum malaria SP‖or ASAQ or AM-L | Once daily of ASAQ or twice daily of AM-L (blister pack) | 3 days | Effectiveness success rate by day 28 ASAQ: 70.5% (67/95) AM-L: 78.1% (75/96) | Remaining drug count | Having taken all prescribed doses | ASAQ: 83.3% (80/96) AM-L: 78.5% (75/96) |

| Achan, 200926 | RCT(Uganda) | 175 children (Quinine: 86, AM-L: 89) | Falciparum malaria Q or AM-L | Q or AM-L blister pack | Q: 7 days AM-L: 3 days | ACPR by day 28 Q: 54.7% (47/86) AM-L: 79.8% (71/89) | Remaining drug count and care givers' report | Percentage of prescribed pills taken | Q: 39.5% (34/86) AM-L: 79.8% (71/89)** |

| Fungladda, 199819 | RCT (Thailand) | 137 patients aged 15–60 years (quinine + tetracycline: 60, artesunate: 77) | Falciparum malaria Q + TT or AS | Q + TT or AS | Q + TT: 7 days AS: 5 days | Negative peripheral blood smear by day 5 Q + TT: 68.3% (41/60) AS: 79.2% (61/77) | Patient interview and remaining drug count | Adherence to the protocol or not missing a single dose of the prescribed treatment | Q + TT: 63.3% (38/60) AS: 77.9% (60/77) |

ACPR = adequate clinical and parasitological response; AM-L = artemether-lumefantrine; ASAQ = artesunate-amodiaquine; AS = artesunate; CQ = chloroquine; CD = chlorproguanil-dapsone; DOT = directly observed treatment; IMCI = integrated management of childhood illness; non-DOT = non-directly observed treatment; NPP = non-prepackaging; NS = not stated; PQ = primaquine; PP = prepackaging; Q = quinine; TT = tetracycline; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SP = sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine.

This group was excluded from data analysis.

Calculated crude number backward from percentage presented.

Assuming compliance of 100% (no report in the manuscript).

No fever, lower parasitemia, and regained normal activity.

Visited by staff daily.

Success rate was 20.8% but adherence rate was not stated.

Statistical significant difference between intervention and control group.

Quality assessment of included studies.

The quality of study design and reporting was defined as low. Thirteen controlled trials were assessed for sources of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias Studies and the methodological quality of controlled clinical trials using the Jadad score. Ten studies were mentioned for randomization however there was insufficient information about sequence generation or allocation concealment.17,19–23,27,29,30,32 None of the studies were described as double blinded. Incomplete outcome data were not addressed in four studies17,21,23,30; all studies were free of selective outcome reporting but other sources of bias were unclear, and thus there was a risk of bias. The Jadad scores for the studies reviewed ranged from 1 to 3 and were mainly associated with inadequate concealment of allocation and absence of blinding. Only six studies calculated sample size based on adherence outcomes17–20,23,25 and three of these had patients as planned.17,18,20

Heterogeneity of the included studies.

Heterogeneity testing showed that data from all 16 studies were not homogeneous (χ2 340.36; degrees of freedom [df] 18; P < 0.001; I2 94.7%). Analysis by type of intervention also showed high heterogeneity among studies in the same intervention groups.

Effect of different interventions to adherence rate.

The interventions used to promote adherence to antimalarial medication can be classified into six main groups: 1) packaging aids (5 studies),17,20,21,25,27 2) visual media (1 study),22 3) combined approaches of visual media and verbal information (2 studies),22,24 4) community education (3 studies),18,23,32 5) medication supervision (2 studies),28,30 and 6) convenient regimens, i.e., once daily medication regimen (2 studies)29,31 or a shorter duration of treatment (2 studies).19,26 The median relative risk (RR) for adherence across 16 studies was 1.4 (IQR 1.2–2.0) compared with no intervention.

(1) Packaging aids:

Prepackaging or blister packs were classified as packaging aids. The adherence rate following the use of packaging aids among the four studies in falciparum malaria ranged from 66.7% to 91.0%, with corresponding median of RR 1.4, IQR 1.1–1.9.17,20,21,27 One of these four studies failed to detect any effect of packaging on adherence to antimalarial drugs in 168 primary school patients.25 In contrast, two RCTs for chloroquine regimen (prepackaged syrup or tablets) consistently showed a greater adherence rate in patients receiving prepackaging medications compared with bulk package (Table 1).20,21 The remaining study on falciparum malaria also showed that prepackaging of chloroquine plus sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine showed a possible trend toward better adherence compared with the control group.27 The only study that investigated the adherence on vivax malaria also showed that blister packaging exhibited a greater adherence to primaquine or chloroquine treatment.17

(2) Visual media:

A pictorial insert without verbal instruction increased the adherence rate when guardians administered chloroquine syrup to children compared with group (51.9% versus 36.5%, P < 0.001).22 There was no study of visual media intervention in adults.

(3) Combined visual media and verbal information:

Two studies used both visual media and verbal information22,24 where the median RR favoring the intervention was 1.7 (IQR 1.4–2.0). Pictorial insert plus verbal instruction exhibited a greater adherence rate when mothers administered chloroquine syrup to their children compared with no such intervention (73.3% versus 36.5%, P < 0.001), although the visual aid alone also improved adherence (73.3% versus 51.9%, P < 0.001).22 This accords with the study of Agyepong and others24 who found that the adherence rate (defined as minimally effective daily dose) in outpatients who received information combined with antimalarial drug labeling (pictorial or writing) increased from 52.7% to 72.3%.

(4) Community education:

Three studies explored the impact of education in the community setting18,23,32 and the median RR of 2.7 (IQR 1.7–22.4) favored adherence. A video plus posters, delivered to villagers in Cambodia also improved adherence to antimalarial drugs from 0.5% to 20.4% (P < 0.001), whereas the poster alone failed to have any impact (P > 0.05) in a 7-day course of quinine plus tetracycline.18 Winch and others23 ran training courses on the diagnosis and treatment of malaria to the persons managing the drug kits. These village managers of the drug kits subsequently counseled parents on the administration method of chloroquine. This intervention substantially increased the adherence rate to chloroquine from 21.6% to 71.7%. Kangwana and others32 also showed that the provision of subsidized packs of pediatric ACT to retail outlets, training of retail staff and community awareness activities improved antimalarial adherence from 49.4% to 66.5%.

(5) Medication supervision:

Two RCTs, one on falciparum and one on vivax malaria, using supervised dosing or directly observed treatment (DOT), showed a high adherence rate to antimalarial medication.28,30 In a study on falciparum malaria, the adherence rate in the non-directly observed treatment (non-DOT) group was high (149 of 160; 93.1%), although statistical testing comparing to DOT was not reported.28 Another study undertaken on vivax malaria found that DOT achieved a 100% adherence rate during a 14-day primaquine treatment, which is higher than the self-administration group (80.4%).30

(6) Convenient regimen:

The treatment regimen was either as i) once daily dosing or ii) short treatment duration.

-

(ii)

Once daily dosing: Two RCTs explored the impact of once daily dosing on adherence to antimalarial medication and showed a median RR 1.2 (IQR 1.1–1.4).29,31 Dunyo and others31 carried out an RCT where once daily chlorproguanil-dapsone showed a superior adherence rate compared with a twice daily artemether-lumefantrine regimes. This accords with Faucher and others29 who also showed a better adherence rate for once daily artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ) versus artemether-lumefantrine twice daily also among children.

-

(ii)

Short duration of treatment: The two studies investigated the effect of duration of treatment and a shorter medication period showed better adherence: median RR 1.6 (IQR 1.2–2.0).19,26 Adherence was also much improved in the Achan and others26 study where patients underwent a 3-day course of artemether plus lumefantrine (79.8% adherence) were compared with those treated with quinine for 7 days (39.5%). However, Fungladda and others19 in a RCT showed no difference in adherence rate when comparing a 7-day quinine plus tetracycline to 5 days of artesunate (P > 0.05).

Effect of adherence promoting interventions on treatment outcomes.

In addition to adherence, treatment efficacy was also measured in 10 studies on the following interventions: packaging aids (2 studies),20,27 visual media (1 study),22 combined approach of visual media and verbal information (1 study),22 medication supervision (2 studies),28,30 and convenient regimen (4 studies).19,26,29,31 Various types of treatment outcomes (e.g., cure rate, adequate clinical and parasitological response rate, reappearance rate, clinical failure rate) were investigated among these studies. Although most studies showed improvement in adherence rate after intervention, the positive impact on treatment outcomes was not observed.17,18,21,23–25,32 Only DOT over 14 days of treatment of vivax malaria showed a significant reduction in reappearance rate compared with non-DOT.30

Discussion

The present review evaluated a group of different interventions designed to promote adherence to antimalarial medications and teasing out the relative importance of each interventions in a new perspective. Our findings suggested that a combined approach of visual media and verbal information and community education are potential interventions to improve adherence to antimalarial drugs. These results are consistent with those of other studies and suggest that multifaceted interventions featuring interactive education and training have been shown to help promote adherence across a variety of conditions33; this thorough review of the current evidence is useful to accommodate WHO treatment guidelines in enhancing adherence to antimalarial medication.

Neither visual media nor verbal information alone were sufficient to promote adherence to antimalarial drugs however, when combined, an improved adherence among children who were dosed by caregivers is noteworthy.22,24 This review produced results that corroborate the findings from previous work, which explored the use of combination interventions to promote adherence.34,35 Community education (i.e., training of drug kit managers, shopkeepers, retailers, or other dispensers, and promoting public awareness) could increase the understanding of malaria treatment and indirectly improve patient's adherence to antimalarial drugs.18,23,32 There were various educational techniques used for promoting adherence to antimalarials. Acceptability or popularity among the patients, feasibility, and the role of responsible healthcare workers should be taken into account as factors for selection of an appropriate educational technique. For example, video parlors were used to educate community members in Cambodia where it is a very popular medium,18 whereas managers of village drug-kits were well established in southern Mali and therefore were used to educate parents or caregivers of patients with malaria.23

Findings from the included studies on convenient medication regimens were insufficient to conclude that such interventions are effective in improving adherence to antimalarial medications. This is because the once daily dosing regimen of ACT and short treatment duration seem to demonstrate a better benefit in improving adherence in only some of the studies reviewed.29,31 Another drawback in interpreting findings in this type of intervention was caused by the minimal validity of the included studies.19,26,29,31 This is because the studies were not randomized into two equal groups and employment of two different antimalarial drugs. This was deemed as a major confounder to the outcomes observed as those who received older medications (e.g., chloroquine, quinine plus tetracycline) may not adhere well to their medication of the lower efficacies and more numerous side effects, whereas patients on new treatments (e.g., ACTs) were more likely to complete the treatment course.19 The positive impact of convenient regimen should therefore be interpreted as a combined influence of the antimalarial drug itself and its frequency of administration.

Packaging aids and medication supervision may improve adherence to antimalarial drugs; although the effect remains inconclusive. Afenyadu and others25 showed no difference in adherence rate between patients receiving pre-packaged and non-prepackaged chloroquine. However, this study seemed underpowered to detect differences between the groups. In contrast, results from three other RCT studies showed that packaging aids improved patient adherence to antimalarial drugs, which was consistent with the previous review.10 Likewise, studies evaluating the impact of medication supervision on adherence provided mixed results. A study of 320 patients in Bangladesh exhibited a high adherence rate in the non-DOT group28; the authors of this study suggested that a DOT-like approach of drug delivery may not be necessary. However, selection bias was observed in this study because patients who tended to adhere to the medication, indicated by the ability to attend follow-up visits, were included in the study, whereas those unable to attend follow-up visits were excluded.

In addition to the adherence-promoting interventions identified in this review, mobile phone short message service (SMS) may be an alternative intervention to improve antimalarial drugs adherence. A review by Fjeldsoe and others36 on the use of SMS text messaging for behavior change among patients in clinical care and for clients in preventive health behaviors interventions found participant retention ranging from 43% to 100% and a great variability in acceptance and compliance with the SMS programs. Furthermore, a study in Thailand showed that the mobile phone-based case follow-up rate was higher than previous paper-based case follow-up, and adherence to antimalarials was 94% for Plasmodium falciparum-infected patients and 42.6% for Plasmodium vivax cases.37 However, comparative studies are needed to confirm the benefit of SMS text messaging to patient adherence to antimalarial drugs.

The strength of our study is that we have used extended databases and a timeline beyond the previous systematic review,10 which allowed us to include an additional nine comparative studies.23,25–32 Considering the information from these recent studies, an additional intervention, i.e., convenient dosing regimen, has been identified and described.10 Standard assessment tools (i.e., the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Studies and Jadad score) were also used to assess the methodology of the included studies. This allows the reader to justify quality of the study available in this area.

Despite the vigorous bibliographic search of relevant publications, the high heterogeneity precluded a meta-analysis for different intervention types. Possible causes of heterogeneity were diversities in study design, intervention approach, comparators, treatment regimes, treatment duration, and methods to evaluate adherence to antimalarial drugs. This heterogeneity is a common problem found in systematic reviews including those studying medication adherences in other types of treatment, such as cardiovascular drugs.38,39 In addition, this was also reflected in the wide variation in baseline adherence rates between different studies. There was no readily identifiable cause for this but the national setting, epoch of the study, antimalarial regimen, general educational level, medical policies (including how the drugs are paid for), and concurrent treatments probably all made contributions to this immense disparity.

The definitions for adherence were only described in a small proportion of the studies and they were various. The rate of adherence to antimalarial drugs presented in this review is, therefore, not uniformly defined throughout the different included studies nor is the methodology used to assess adherence. Basically, it should clearly state the number of doses consumed and their frequency, size, and the treatment duration. Like many diseases, defining what constitutes adequate medication adherence is a complex issue. A working general definition of adequate adherence in clinical practice is the minimum level of adherence required for each person to achieve adequate treatment response and avoid relapse that is mutually agreed upon by patient and healthcare professionals. Although, there is no clear consensus at this time on which cutoff to use and the choice may depend on the specific aims of each study. Future studies should tailor a categorical definition using evidence-based treatment parameters, for examples, by adding a minimally effective dose to the percent use over time or to a minimal duration of treatment. Definition of adequate adherence should also take into account the possibility of excessive use of medication, or overdosing.

Measurement of medication adherence remains a challenge in routine practice and the research field. Although electronic pill boxes have been suggested as an appropriate approach to evaluate adherence to medication,40 they have their own problems and being too expensive in regions where malaria is endemic. Because all adherence measures have strengths and weaknesses, it is generally recommended that investigations combine two or more potentially complementary measures of adherence. Selection of the approach in evaluating adherence should depend on the type of adherence, intervention target, nature of research, and the treatment being investigated. Minimally, adherence studies should follow CONSORT guidelines41; these may help researchers to improve their measurement of adherence in drug effectiveness studies.

Additional factors that are likely to have an impact on the findings of this review include: inadequacy in prescribing and dispensing antimalarials by health professionals, accessibility to healthcare facilities, and out-of-pocket payment for the treatment. Another confounding factor affecting the adherence to medication was the particular antimalarial compound per se, as previously mentioned. These factors were not well addressed or clarified in the studies reviewed and therefore need to be considered in future research work to fulfill the existing deficiencies.

The small number of studies in each intervention group may also lead to overinterpretation of the results. Although sample size calculations were conducted in six studies,17–20,23,25 only three stated the number of subjects to detect a genuine effect. It is suggested that matching the test intervention to a three-tier model (e.g., the intervention is targeted to either 1) the whole study population [universal], 2) patients at risk for nonadherence [selected], or 3) those nonadherent [indicated]) has the potential to improve the effect sizes of such adherence studies, and help in providing a structure that facilitates the dissemination and implementation in real world settings.42 It should also be noted that none of the studies reviewed were conducted at a national level. Results from these small-scale studies may only be valid in certain areas or communities and may not be able to be extrapolated unless supported by countrywide studies. Considering the wide range of current antimalarial drugs, we recommend that further adherence-promoting intervention studies should also extend to other recommended antimalarial regimens (e.g., artesunate-mefloquine [ASMQ] and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine [DHAPQ]) or different preparations (e.g., suppository).

Most of the available studies were at an unclear risk of bias and had low Jadad scores caused by poor details on the randomization method or nondisclosure of the method used for sequence generation or allocation sequence. However, some criteria may not apply to certain interventions (e.g., behavior change interventions). For example, almost all of the studies reviewed, most notably the failed “blinding” criterion because of practical difficulties to blind both patients and most of the researchers17–32; although, these types of intervention studies are not amenable to double blinding, there was no information about how interactions between the control and intervention groups were minimized.

Poor adherence continues to be a major problem in malarial treatment. Although some single interventions (such as short-course treatment regimen and user-friendly packaging) were adopted in routine practice, more than one potential intervention should be added on top of the existing ones to summate their beneficial effects in the real world. Further studies should also explore whether those described interventions are actually implemented in routine treatment contexts. This systematic review implies that community education and a visual media/verbal information combination will be of major benefit to adherence thus augmenting the cost-effectiveness of malarial containment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Norman Scholfied for the support and assistance in proofreading the manuscript and valuable comments.

Disclaimer: The authors declare they have no financial competing interest.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Anjana Fuangchan and Teerapon Dhippayom, Pharmaceutical Care Research Unit, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Naresuan University, Muang, Phitsanulok, Thailand, E-mails: anjana.fuangchan@gmail.com and teerapond@hotmail.com. Chuenjid Kongkaew, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Naresuan University, Muang, Phitsanulok, Thailand, E-mails: chuenjidk@nu.ac.th or chuenjid@googlemail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Fact Sheet Malaria. 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/ Available at. Accessed October 31, 2011.

- 2.Sachs J, Malaney P. The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:680–685. doi: 10.1038/415680a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White NJ, Olliaro PL. Strategies for the prevention of antimalarial drug resistance: rationale for combination chemotherapy for malaria. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:399–401. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)10055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloland PB. Drug Resistance in Malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachur SP, Khatib RA, Kaizer E, Fox SS, Abdulla SM, Bloland PB. Adherence to antimalarial combination therapy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and artesunate in rural Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:715–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fogg C, Bajunirwe F, Piola P, Biraro S, Checchi F, Kiguli J, Namiiro P, Musabe J, Kyomugisha A, Guthmann JP. Adherence to a six-dose regimen of artemether-lumefantrine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:525–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabanywanyi AM, Lengeler C, Kasim P, King'eng'ena S, Schlienger R, Mulure N, Genton B. Adherence to and acceptability of artemether-lumefantrine as first-line anti-malarial treatment: evidence from a rural community in Tanzania. Malar J. 2010;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beer N, Ali AS, Rotllant G, Abass AK, Omari RS, Al-Mafazy AW, Bjorkman A, Kallander K. Adherence to artesunate-amodiaquine combination therapy for uncomplicated malaria in children in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:766–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeung S, White NJ. How do patients use antimalarial drugs? A review of the evidence. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:121–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org Available at. Accessed March 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Son Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;11:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2008. www.cochrane-handbook.org Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qingjun L, Jihui D, Laiyi T, Xiangjun Z, Jun L, Hay A, Shires S, Navaratnam V. The effect of drug packaging on patients' compliance with treatment for Plasmodium vivax malaria in China. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76((Suppl 1)):21–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denis MB. Improving compliance with quinine + tetracycline for treatment of malaria: evaluation of health education interventions in Cambodian villages. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76((Suppl 1)):43–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fungladda W, Honrado ER, Thimasarn K, Kitayaporn D, Karbwang J, Kamolratanakul P, Masngammueng R. Compliance with artesunate and quinine + tetracycline treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76((Suppl 1)):59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ansah EK, Gyapong JO, Agyepong IA, Evans DB. Improving adherence to malaria treatment for children: the use of pre-packed chloroquine tablets vs. chloroquine syrup. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:496–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeboah-Antwi K, Gyapong JO, Asare IK, Barnish G, Evans DB, Adjei S. Impact of prepackaging antimalarial drugs on cost to patients and compliance with treatment. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:394–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okonkwo PO, Akpala CO, Okafor HU, Mbah AU, Nwaiwu O. Compliance to correct dose of chloroquine in uncomplicated malaria correlates with improvement in the condition of rural Nigerian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winch PJ, Bagayoko A, Diawara A, Kane M, Thiero F, Gilroy K, Daou Z, Berthe Z, Swedberg E. Increases in correct administration of chloroquine in the home and referral of sick children to health facilities through a community-based intervention in Bougouni District, Mali. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)80001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agyepong IA, Ansah E, Gyapong M, Adjei S, Barnish G, Evans D. Strategies to improve adherence to recommended chloroquine treatment regimes: a quasi-experiment in the context of integrated primary health care delivery in Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:2215–2226. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afenyadu GY, Agyepong IA, Barnish G, Adjei S. Improving access to early treatment of malaria: a trial with primary school teachers as care providers. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1065–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achan J, Tibenderana JK, Kyabayinze D, Wabwire Mangen F, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, D'Alessandro U, Rosenthal PJ, Talisuna AO. Effectiveness of quinine versus artemether-lumefantrine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Ugandan children: randomized trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2763. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauwo JA, Hombhanje FW, Tulo SP, Maibani G, Bjorge S. Impact of pre-packaging antimalarial drugs and counseling on compliance with malaria treatment at Port Moresby General Hospital Adult Outpatient Department. P N G Med J. 2006;49:14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman MM, Dondorp AM, Day NPJ, Lindegardh N, Imwong M, Faiz MA, Bangali AM, Kamal AT, Karim J, Kaewkungwal J, Singhasivanon P. Adherence and efficacy of supervised versus non-supervised treatment with artemether/lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Bangladesh: a randomized controlled trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faucher JF, Aubouy A, Adeothy A, Cottrell G, Doritchamou J, Gourmel B, Houze P, Kossou H, Amedome H, Massougbodji A, Cot M, Deloron P. Comparison of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, unsupervised artemether-lumefantrine, and unsupervised artesunate-amodiaquine fixed-dose formulation for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Benin: a randomized effectiveness noninferiority trial. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:57–65. doi: 10.1086/599378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeuchi R, Lawpoolsri S, Imwong M, Kobayashi J, Kaewkungwal J, Pukrittayakamee S, Puangsa-Art S, Thanyavanich N, Maneeboonyang W, Day NP, Singhasivanon P. Directly-observed therapy (DOT) for the radical 14-day primaquine treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria on the Thai-Myanmar border. Malar J. 2010;9:308. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunyo S, Sirugo G, Sesay S, Bisseye C, Njie F, Adiamoh M, Nwakanma D, Diatta M, Janha R, Sisay Joof F, Temple B, Snell P, Conway D, Walton R, Cheung YB, Milligan P. Randomized trial of safety and effectiveness of chlorproguanil-dapsone and lumefantrine-artemether for uncomplicated malaria in children in the Gambia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kangwana BP, Kedenge SV, Noor AM, Alegana VA, Nyandigisi AJ, Pandit J, Fegan GW, Todd JE, Brooker S, Snow RW, Goodman CA. The impact of retail-sector delivery of artemether-lumefantrine on malaria treatment of children under five in Kenya: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B. Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2005;22:313–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02850081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berben L, Bogert L, Leventhal ME, Fridlund B, Jaarsma T, Norekval TM, Smith K, Stromberg A, Thompson DR, De Geest S. Which interventions are used by health care professionals to enhance medication adherence in cardiovascular patients? A survey of current clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu YP, Roberts MC. A meta-analysis of interventions to increase adherence to medication regimens for pediatric otitis media and streptococcal pharyngitis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:789–796. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meankaew P, Kaewkungwal J, Khamsiriwatchara A, Khunthong P, Singhasivanon P, Satimai W. Application of mobile-technology for disease and treatment monitoring of malaria in the “Better Border Healthcare Programme”. Malar J. 2010;10:69. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowry AD, Shrank WH, Lee JL, Stedman M, Choudhry NK. A systematic review of adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1479–1491. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1825-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandercock P. The authors say: ‘The data are not so robust because of heterogeneity’ - so, how should I deal with this systematic review? Meta-analysis and the clinician. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:615–620. doi: 10.1159/000326068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Twagirumukiza M, Kayumba PC, Kips JG, Vrijens B, Stichele RV, Vervaet C, Remon JP, Van Bortel ML. Evaluation of medication adherence methods in the treatment of malaria in Rwandan infants. Malar J. 2010;9:206. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:e1–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velligan D, Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Riley WT, Safren S, Lewis-Fernandez R, Weiden P, Ogedegbe G, Jamison J. Methodological challenges in psychiatric treatment adherence research. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4:74–91. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.4.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]