Abstract

Background

Scholarly activity during residency is vital to resident learning and ultimately to patient care. Incorporating that activity into training is, however, a challenge for medical educators. Most research on medical student and resident attitudes toward scholarly activity to date has been quantitative and has focused on level of interest, desire to perform scholarship, and perceived importance of scholarship.

Objective

We explored attitudes, expectations, and barriers regarding participation in scholarly activity among current residents and graduates of a single family medicine residency program.

Methods

Using a phenomenologic approach, we systematically analyzed data from one-on-one, semistructured interviews with residents and graduates. Interviews included participant expectations and experiences with scholarly activity in residency.

Results

The 20 participants (residents, 15 [75%]; residency graduates, 5 [25%]) identified uncertainty in their attitudes toward, and expectations regarding, participation in scholarly activity as an overarching theme, which may present a barrier to participation. Themes included uncertainty regarding their personal identity as a clinician, time to complete scholarly activity, how to establish a mentor-mentee relationship, the social norms of scholarship, what counted toward the scholarship requirements, the protocol for completing projects, and the clinical relevance of scholarship.

Conclusions

Uncertainty about scholarly activity expectations can add to learner anxiety and make performing scholarly activity during residency seem like an insurmountable task. Programs should consider implementing a variety of strategies to foster scholarly activity during residency, including clarifying and codifying expectations and facilitating mentoring relationships with faculty.

What was known

Scholarly activity is an important component of the formal education of physicians.

What is new

Interviews with residents and alumni from a single family medicine residency program find that uncertainty regarding program and social and personal expectations are barriers to scholarly activity.

Limitations

Single-site, single-specialty focus, and small, primarily male, sample limit generalizability.

Bottom line

Programs should clarify expectations regarding scholarly activity during residency and facilitate mentoring relationships with faculty.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the interview guide (46.5KB, doc) used in this study.

Introduction

Scholarly activity is a vital part of graduate medical education. Not only does scholarship education provide residents with the skills needed to become future clinical researchers, but it also develops vital skills important to their ability to provide high-quality patient care. These skills include conducting a targeted literature search, critically appraising medical literature, and applying medical research to clinical scenarios.1

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) standards have increased requirements for scholarly activity in recent years.2 Translating these requirements into successful educational programs and actual scholarly production has remained a difficult challenge for medical educators.3 Despite a significant body of literature that identifies specific features of programs that are associated with high levels of resident scholarly productivity, there is evidence that resident scholarship continues to lag.4–6 Particularly in primary care specialties, there is a sense of frustration with the perceived and real barriers to scholarly activities, and an overall lack of resident scholarly production.3,7,8 Many factors likely contribute to this, including limited time, lack of funding, difficulty identifying mentors, and lack of technical support,2,6 as well as the level of interest in scholarship by medical students who pursue primary care.9

Most studies on medical student and resident attitudes toward research have been quantitative and have focused on levels of interest, desire to perform scholarship, and perceived importance of scholarship. To date, no studies have examined the effect of resident expectations on their ultimate scholarly experience in residency or whether a resident's desire to perform scholarship can be positively affected through either education or curriculum design. This study is the first, to our knowledge, to apply qualitative methods to these questions in the context of a US family medicine residency. Our study purpose was to identify attitudes, expectations, and barriers regarding active participation in scholarly activity among current residents and graduates of 1 family medicine residency program.

Methods

Using a phenomenologic approach, our study systematically analyzed participant reports of their expectations and experiences with scholarly activity in the family medicine residency program.10,11 The addition of qualitative research methods can be used to describe learners' expectations and levels of preparedness to participate in scholarship during residency, particularly the “why” and “how” of their scholarly experience.10 Purposive sampling12 included current family medicine residents and graduates from the residency program within 5 years who lived locally (who were thus available for an in-person interview). The recruitment strategy was designed to include a longitudinal perspective of scholarship in the residency, capturing perspectives from graduates who could judge the value of the experience in the context of practice, and perspectives from current residents. Participant recruitment included group announcements and e-mail solicitations to current family medicine residents and graduates. Volunteers did not receive an incentive or compensation for their participation.

Researchers used an open-ended, semistructured interviewing style to gather data in April and May 2011. All interviews were conducted in person by 2 authors (C.J.W.L. and M.M.V.) who were unaffiliated with the residency program at a time and hospital location chosen by the participant. Another author (M.A.C.), a residency faculty member, coordinated logistic requirements for conducting interviews.

The interview guide was designed according to the literature review presented here. The interview questions addressed scholarship experiences, scholarship success, and barriers to scholarship success (provided as online supplemental material). The interviewers recorded handwritten field notes throughout the interview and additional notes of impressions following the interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Participants gave consent before agreeing to the interviews, and the study was reviewed and received exemption by the local Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis began as soon as the first interview was conducted.13 Each set of interview field notes was reviewed by 2 of the authors to discern information about potential themes. Transcripts were carefully reviewed several times to build an interpretative framework for qualitative analysis. The analytic approach included both exploring a prior research interest (eg, what barriers exist for resident scholarship?) and searching for emergent themes.

The complete qualitative data set was coded and analyzed using NVivo 9 (Burlington, MA) qualitative software.14 The authors used an open coding process to identify recurrent, unifying concepts about resident scholarship experiences,15–17 analyzed transcripts line by line, and recorded conceptual codes as they emerged.13 The unit of analysis for coding was each physician statement. Axial coding then related subcategories and further developed the categories. The constant comparative method was used to saturate categories.17–19 These 2 analysis methods (computer-aided and dual coder) were collapsed for triangulation of the data.

As a validation strategy, 6 participants (30%) reviewed the results section as a member check, judging the accuracy and credibility of the findings.11 Additionally, 3 subject matter experts in family medicine reviewed findings as a peer check, providing content validity.11

Results

Participants

We approached 28 residents and residency graduates for our study, and our participation rate was 71% (20 of 28), with 15 of 22 residents (68%) and 5 of 6 graduates (83%) participating. Interviews lasted between 10 and 42 minutes (x̄ = 23.41, SD = 9.15). Participants' experience ranged from 1 to 8 years (x̄ = 3.35, SD = 2.46). Four of the 20 participants (20%) were women.

Emerging Themes

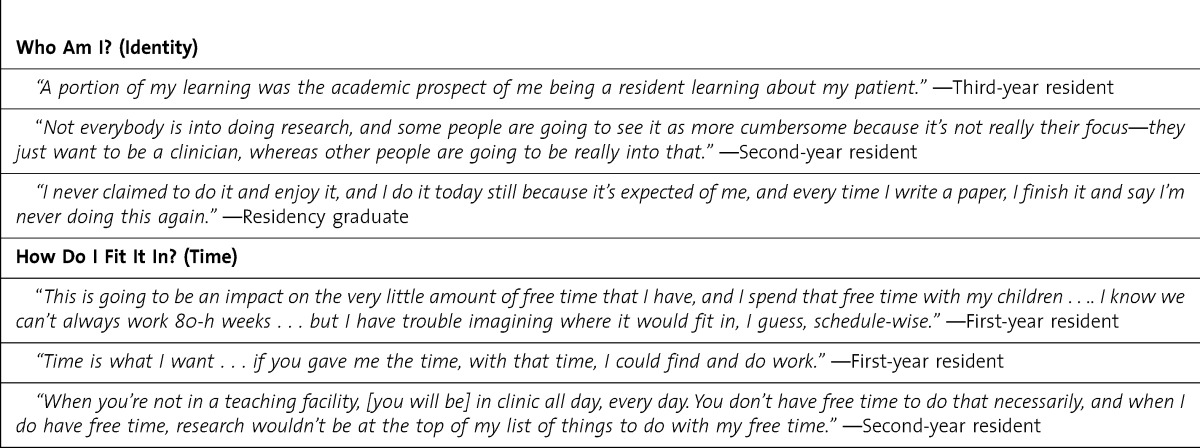

Participants identified uncertainty as an overarching theme in their attitudes toward, expectations regarding, and barriers to active participation in scholarly activity. At the individual level, participants described 2 themes of uncertainty. First, they questioned their personal identity as a clinician as it related to scholarship. Second, they expressed uncertainty about having time to complete a scholarly activity (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Individual Uncertainty Themes Regarding Scholarly Activity

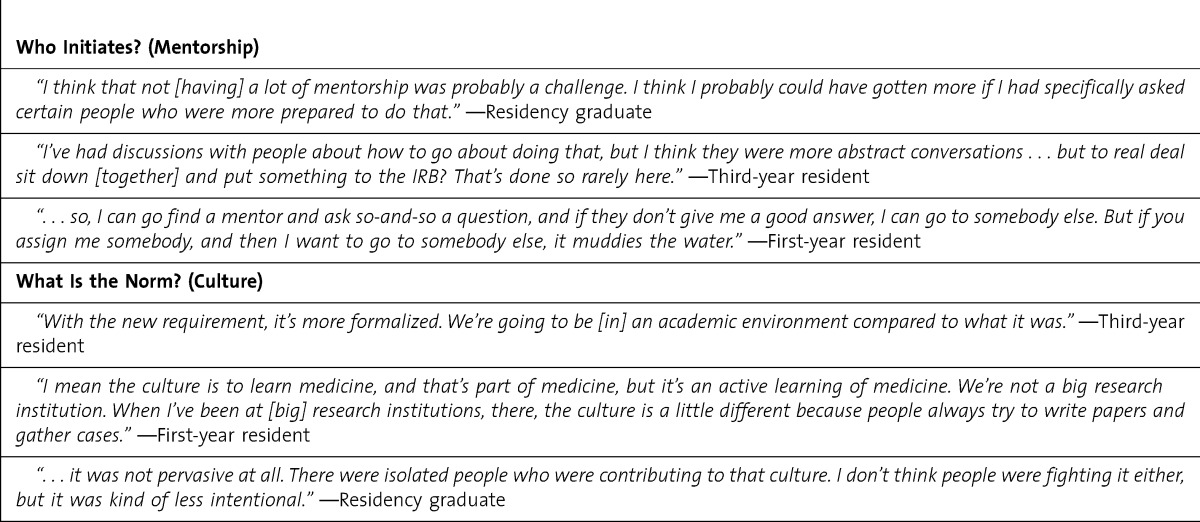

Themes emerged at the relational level between mentor-mentee and among peers. Although participants recognized that family medicine faculty could be valuable in the scholarship process and perceived them as willing to help, participants were uncertain how to establish a mentor-mentee relationship. Also, participants expressed uncertainty regarding the social norms of scholarship: who was completing scholarship, the amount of scholarship successfully accomplished, and peer and faculty expectations regarding scholarship (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relational Uncertainty Themes Regarding Scholarly Activity

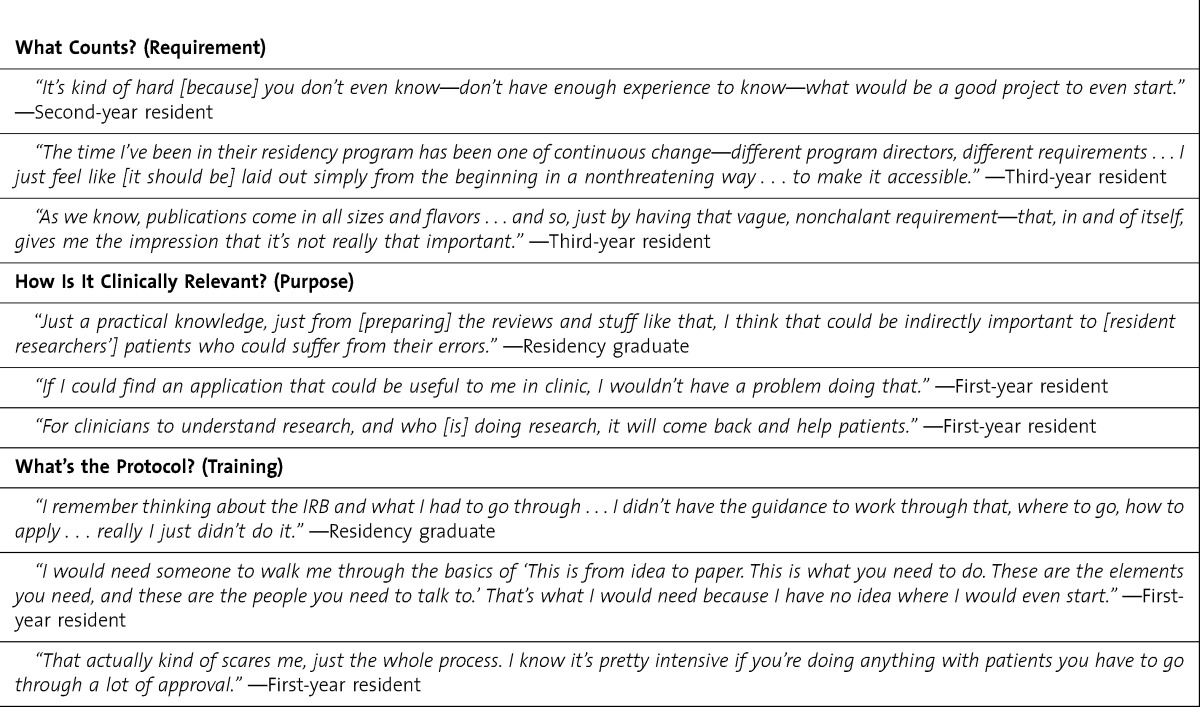

The greatest number of themes of uncertainty emerged at the structural level. Foremost, participants described uncertainty regarding what counted toward the scholarship requirement and voiced specific uncertainty about the types of scholarship (ie, case reports, observational studies, controlled trials) that would fulfill the requirement. They also questioned the clinical relevance of scholarship and the protocol for completing projects, including various methodologies and logistic processes (table 3).

TABLE 3.

Structural Uncertainty Themes Regarding Scholarly Activity

Discussion

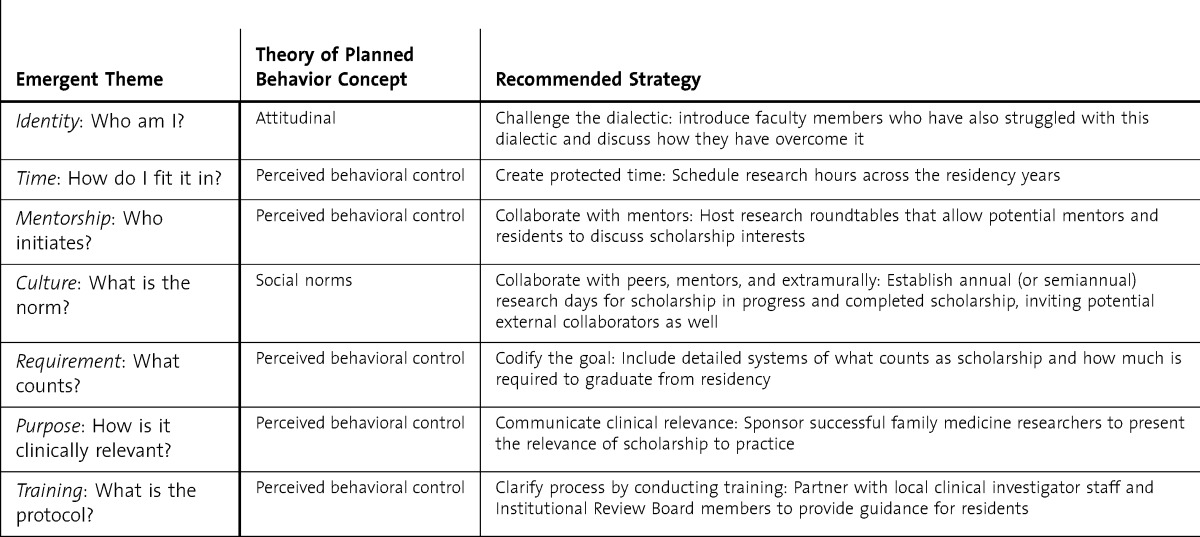

Uncertainty and diverse expectations emerged as barriers to active participation in scholarly activity among family medicine residents. However, unlike many of the near-universal barriers to scholarship, such as time, money, and expertise, it is possible to address this barrier with minimal expenditure of resources. The “Theory of Planned Behavior” postulates that individuals formulate their intended behaviors through a process of incorporating attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control.20 table 4 presents recommendations for strategies to address each uncertainty theme.

TABLE 4.

Strategies to Address Barriers of Uncertainty Regarding Scholarly Activity

Our results showed that attitudinal barriers included identity and clinical relevance. Participant physicians recognized the clinician-researcher as a dialectic,21 a complex relationship between 2 opposites. Participants reported feeling pressure to be both clinician and researcher while perceiving them as mutually exclusive. A strategy to address that uncertain attitude is to challenge that dialectic by demonstrating the intersection of scholarship and clinical medicine, such as performing literature searches to answer a clinical question or generating a research hypothesis from a clinical question. This finding particularly aligns with existing curricular goals of some residencies, which include attitudes, goals, appreciation of scholarship, and willingness to be involved in scholarly projects.22

Attitudes toward the clinical relevance of scholarship activity were also uncertain. Our results replicated findings from Canadian family medicine residents who expressed a need for understanding the clinical relevance of a scholarship requirement.23 The goals of mandating resident scholarship must be clearly communicated to create positive attitudes toward scholarship. Residents need to understand that scholarship is an educational process intended to move them toward a goal, not the goal itself.

There also was uncertainty about social norms. Establishing positive social norms toward research can influence resident intent to engage in scholarship. Residents should be encouraged to form scholarly partnerships with peers, faculty, and outside collaborators, as appropriate. More frequent attention to resident scholarship and integration into established schedules, through morning report presentations, journal clubs, formalized interest groups,24 or lunch roundtables, can increase peer collaboration and influence positive social norms.

The remaining uncertainty themes were linked to perceptions in behavioral control. Time is a precious commodity in residency but is one that must be allocated in a protected manner if residents are expected to accomplish scholarship worthy of publication or presentation.2,25 Dedicating time demonstrates that the residency leadership truly values scholarship and providing time early in the residency recognizes the longitudinal nature of scholarship and its effect.26

To address requirement uncertainty, programs can codify the goal. The process of performing scholarly activity and meeting the program's requirement also needs to be presented clearly to decrease resident anxiety and reduce the “fear of the unknown.” Similarly, uncertainty about training can be addressed through clarifying the process of scholarship to include protocol development, regulatory affairs, and human subjects protection. Along with clearly describing the process, training must be provided to ensure residents feel confident with not only the logistic process but also the mechanics of scholarship, such as design, methodology, analysis, and dissemination.

Lastly, our findings demonstrate residents' recognition of the value of mentorship in collaboration; however, they perceived little control in establishing mentor relationships. In the academic environment, it is common for the learner to perceive himself or herself as having low control or power.27 Additionally, in the medical academic environment, learners perceive the need to maintain the hierarchy by not challenging, or even approaching, senior physicians.28 A structural strategy is to host scholarship “mixers,” where faculty and residents recognize the role of the event is to establish mentorships and to loosely share and discuss interests and projects. Another strategy for addressing mentorship needs is to assign or match faculty mentors to residents.29,30 Although resource challenging, 1 characteristic of a successful residency scholarship program is the funding of faculty time devoted to scholarship mentoring.31

As residents are continually exposed to scholarship and scholarly projects are successfully completed, expectations about the performance of scholarship will change. As expectations change, attitudes toward scholarship will evolve. A changed attitude toward scholarly activity will result in, with proper cultivation by motivated faculty, a culture of inquiry among residents.32

Our study has several limitations. Qualitative analysis relies on thematic saturation.19 However, some of the saturation we achieved in our study could be explained by the training setting and its single-site nature. Purposive sampling also resulted in a sample that was 75% male, and female resident perspectives may not have reached comparable saturation. Additionally, this residency program was experiencing a transition in leadership, which could have influenced resident perceptions.

Conclusion

Participants identified uncertainty as an overarching theme in their attitudes toward, expectations regarding, and barriers to active participation in scholarly activity. Uncertainty about personal, social, and program expectations can add to learner anxiety and make performing scholarly activity during residency seem like an insurmountable task. Programs should consider implementing a variety of strategies to foster scholarly activity during residency, including clarifying and codifying expectations and facilitating mentoring relationships with faculty.

Footnotes

Christy J. W. Ledford, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Biomedical Informatics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Dean A. Seehusen, MD, MPH, is Program Director of the National Capital Consortium Family Medicine Residency, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital; Melinda M. Villagran, PhD, is Professor of Communication Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos; Lauren A. Cafferty, BA, is Research Associate of Biomedical Informatics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; and Marc A. Childress, MD, is Faculty Physician of Family Medicine, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense or the United States government.

References

- 1.Carek PJ, Mainous AG., III The state of resident research in family medicine: small but growing. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(suppl 1):2–4. doi: 10.1370/afm.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seehusen DA, Weaver SP. Resident research in family medicine: where are we now. Fam Med. 2009;41(9):663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford P, Seehusen D. Scholarly activity in family medicine residency programs: a national survey. Fam Med. 2011;43(5):311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeHaven MJ, Wilson GR, Murphree DD. Developing a research program in a community-based department of family medicine: one department's experience. Fam Med. 1994;26(5):303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeHaven MJ, Wilson GR, O'Connor-Kettlestrings P. Creating a research culture: what we can learn from residencies that are successful in research. Fam Med. 1998;30(7):501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill S, Levin A, Djurdjev O, Yoshida EM. Obstacles to residents' conducting research and predictors of publication. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):477. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ullrich N, Botelho CA, Hibberd P, Bernstein HH. Research during pediatric residency: predictors and resident-determined influences. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1253–1258. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine RB, Hebert RS, Wright SM. Resident research and scholarly activity in internal medicine residency training programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Family medicine specialty choice and interest in research. Fam Med. 2005;37(4):265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan GM, Sargeant J. Qualities of qualitative research: part I. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(4):449–452. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00221.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creswell JW. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sargeant J. Qualitative research part II: participants, analysis, and quality assurance. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):1–3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00307.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.QSR International. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Doncaster, Victoria, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser BG. Conceptualization: on theory and theorizing using grounded theory. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1(2):23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Research: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrad CF. A grounded theory of academic change. Sociol Educ. 1978;51(April):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res. 1995;5(2):147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin JN, Nakayama TK. Intercultural Communication in Contexts. 5th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill Higher Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert RS, Levine RB, Smith CG, Wright SM. A systematic review of resident research curricula. Acad Med. 2003;78(1):61–68. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo J, Bains J, Collins MB, Dharamsi S. Residency research requirements and the CanMEDS-FM scholar role: perspectives of residents and recent graduates. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(6):e330–e336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohlwes RJ, Cornett P, Dandu M, Julian K, Vidyarthi A, Minichiello T, et al. et al. Developing educators, investigators, and leaders during internal medicine residency: the area of distinction program. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(4):535–540. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00029.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hepburn MJ, Battafarano DF, Enzenauer RJ, Salzberg DJ, Murphy FT, Parisek RA, et al. Increasing resident research in a military internal medicine program. Mil Med. 2003;168(4):341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth DE, Chan MK, Vohra S. Initial successes and challenges in the development of a pediatric resident research curriculum. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):149–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale T, Cosgrove D. “We learnt that last week”: reading into the language practices of teachers. Teach Teach Theory Pract. 2004;10(2):125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 1):16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurahara DK, Kogachi K, Yamane M, Ly CL, Foster JH, Masaki-Tesoro T, et al. A pediatric residency research requirement to improve collaborative resident and faculty publication productivity. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71(8):224–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivera JA, Levine RB, Wright SM. Completing a scholarly project during residency training. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):366–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carek PJ, Dickerson LM, Diaz VA, Steyer TE. Addressing the scholarly activity requirements for residents: one program's solution. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):379–382. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00201.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stange KC, Miller WL, McWhinney I. Developing the knowledge base of family practice. Fam Med. 2001;33(4):286–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]