Abstract

Background

Communicating with colleagues is a key physician competency. Yet few studies have sought to uncover the complex nature of relationships between referring and consulting physicians, which may be affected by the inherent relationships between the participants.

Objective

Our study examines themes identified from discussions about communications and the role of relationships during the referral-consultation process.

Methods

From March to September 2010, 30 residents (10 emergency medicine, 10 general surgery, 10 internal medicine) were interviewed using a semistructured focus group protocol. Two investigators independently reviewed the transcripts using inductive methods and grounded theory to generate themes (using codes for ease of analysis) until saturation was reached. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, yielding an inventory of themes and subthemes. Measures for ensuring trustworthiness of the analysis included generating an audit trail and external auditing of the material by investigators not involved with the initial analysis.

Results

Two main relationship-related themes affected the referral-consultation process: familiarity and trust. Various subthemes were further delineated and studied in the context of pertinent literature.

Conclusions

Relationships between physicians have a powerful influence on the emergency department referral-consultation dynamic. The emergency department referral-consultation may be significantly altered by the familiarity and perceived trustworthiness of the referring and consulting physicians. Our proposed framework may further inform and improve instructional methods for teaching interpersonal communication. Most importantly, it may help junior learners understand inherent difficulties they may encounter during the referral process between emergency and consulting physicians.

What was known

Communicating with colleagues is an important element of physician practice.

What is new

Familiarity and perceived trustworthiness of the referring and consulting residents are critical to the effectiveness of emergency department referrals and consultations.

Limitations

The single modality of data collection and single-site setting limit generalizability.

Bottom line

Understanding communication dynamics may help junior learners navigate difficulties encountered during the referral process between emergency and consulting physicians.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the focus group questions and a comparison of the study's findings (35.5KB, doc) to Giffin's Model of Interpersonal Trust.

Introduction

Both the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada's CanMEDS framework and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the United States have identified the ability to communicate with colleagues as a key competency for all physicians.1,2 Few studies, however, have attempted to uncover factors that influence the interpersonal dynamics between the referring and consulting physicians,3,4 and these studies mostly focus on primary care referrals to specialists on a routine outpatient basis, not emergent consultations.

The referral-consultation process is influenced by the relationships among the participants. Most research on relationships during physician consultations has focused on quantifying and identifying communication problems.3–10 Research has explored nonemergent consultations by family medicine physicians3,4 and the attitudes of consultants during telephone-only consults.5 In the research on urgent or emergent consultations,8–15 most studies sought to define and quantify the emergency department (ED) consultation process.8–13 With the advent of the ACGME core competencies and Milestone Project,16 the teaching and learning of interpersonal and teamwork skills are increasingly highlighted. To our knowledge this is the first study that has explored interpersonal factors that may influence resident communication during the referral-consultation process within the context of the ED. The findings may help to clarify the social dynamics around their interactions with other residents and attending physicians.

Methods

We used a qualitative, grounded theory approach to examine transcripts from semistructured, moderated, focus group discussions. All participants provided written, informed consent. Participants were 30 residents (10 emergency medicine [EM], 10 general surgery [GS], 10 internal medicine [IM]) who participated in discipline-specific focus groups conducted between March and September 2010. Participants represented a convenience sample of residents recruited through the use of repeated contact in a modified Dillman method via e-mail.17,18 They were chosen because the 3 specialties interact most frequently within the ED at our institution. All participants had completed their first year of specialty training and had participated (ie, requesting or delivering consultations multiple times per week) in the ED referral and consultation process in the prior 12 months.

Data Collection

This study was conducted as part of a larger study examining the ED referral-consultation process. We explored the perceptions of residents during this crucial interaction. Our focus group templates (provided as online supplemental material) were designed via consensus among the investigators and piloted on a small sample of nonparticipating faculty members and residents who provided feedback to improve the protocol. Participants were discussants in semistructured focus groups; the 7 focus groups lasted 80 to 96 minutes. The group moderator asked a standard set of questions but was able to ask clarification questions or to prompt participants to explain their comments further. The moderator asked participants about various domains in the ED referral-consultation process, including (1) the structure of the consultation request, (2) techniques to facilitate a consultation, (3) feedback and communication after a referral, and (4) barriers to effective consultation. If they had not already commented on the topic, participants were asked if and how a preexisting relationship affected the referral-consultation process. All focus groups were conducted by a single moderator (T.C.), and were audiotaped. The transcripts were transcribed, and participants’ identities were made anonymous before analysis.

Analysis

Transcripts of the source material were analyzed as a single group regardless of the training program. All transcripts were reviewed by 2 investigators (K.S., S.S.), and all relevant quotes were extracted. Disagreements were resolved by a third investigator (T.C.). Excerpts were then independently reviewed by 2 investigators (T.C., K.S.) and analyzed using inductive approaches associated with grounded theory.19–21 An index of themes was generated until a saturation point was reached and no new themes were generated. Investigators met repeatedly to review their analyses and determine the categories for themes, coalescing commonalities into common themes in an iterative fashion. Discrepancies were resolved by reviewing the original quotes in the context of the transcripts, discussing source material in the context of these themes, and arriving at a decision by consensus.5 To ensure trustworthiness of the analysis, an audit trail was created, and the final master set of themes and associated transcripts were reviewed by a third investigator (S.S.) who was not involved in the inductive process to generate them. Discrepancies noted during the audit were resolved via consensus.

Our study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences/McMaster University Research Ethics Board.

Results

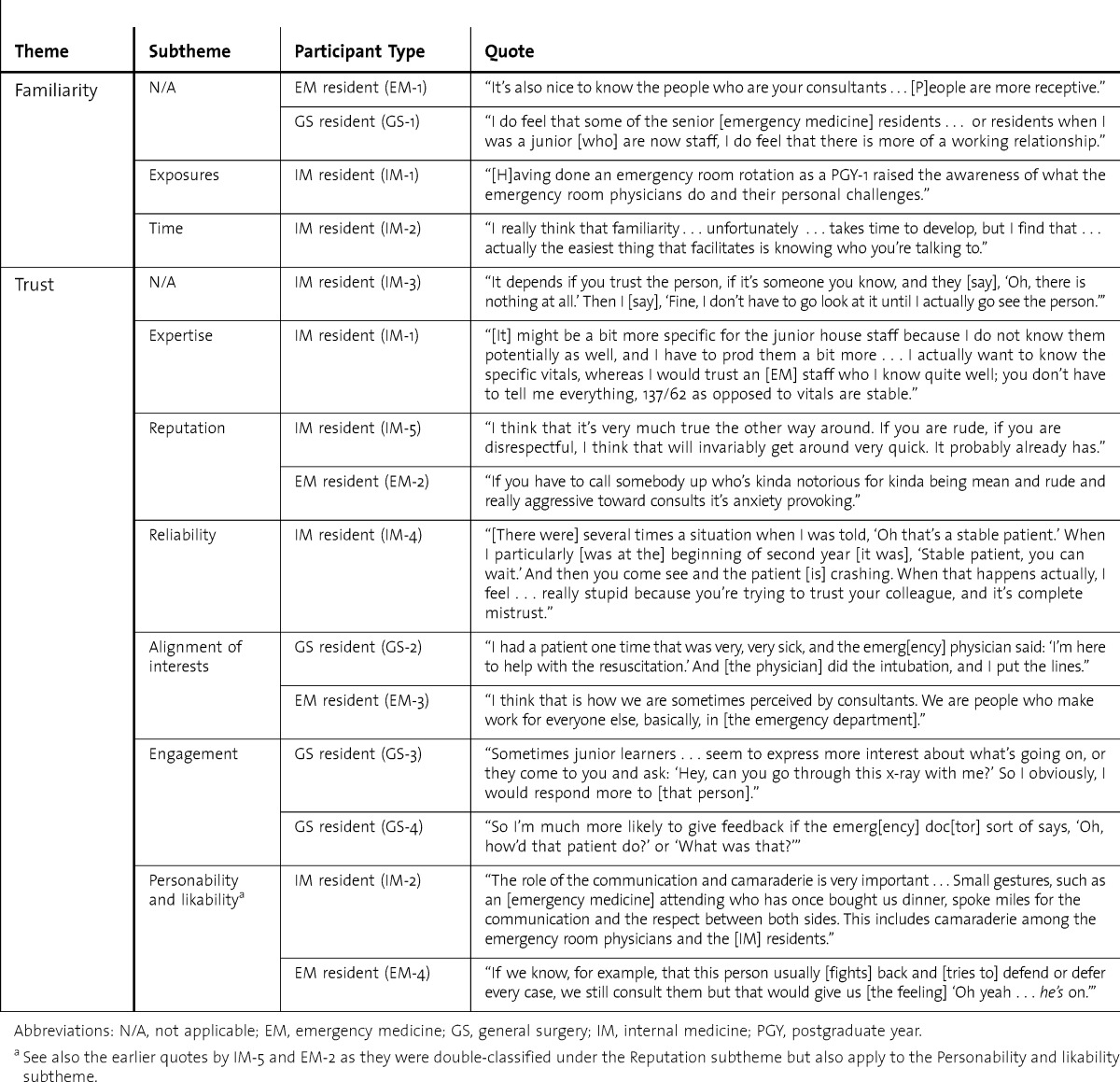

Our findings are a synthesis of the perceptions of residents from all 3 specialty groups (EM, GS, and IM). We identified 2 dimensions of interpersonal relationships that our participants believe influenced the referral-consultation process: familiarity and trust. table 1 shows example quotes that highlight the themes and subthemes described in this section.

TABLE 1.

Exemplar Quotes for Themes and Subthemes

Theme 1: Familiarity

Our analysis suggests that familiarity with another person is a time-dependent function that likely results from interactions over time. Familiarity is developed through extensive exposure that occurs when both parties are aware of each other (ie, not anonymous). Participants reported that more in-depth exposures, such as socializing outside of work, rotating through other services, and sharing educational experiences, helped develop familiarity. The EM residents also commented about the value of in-depth off-service experiences (eg, working with surgical colleagues during an orthopedic rotation) as well as shared collaborative working experiences (eg, resuscitating a patient as a team with an internist). Familiarity is enhanced by repeated exposures over time. Residents commented that they became more collegial with colleagues after repeated exposure. More importantly, participants commented that with time they became more knowledgeable about the practice patterns and management styles of their colleagues. Participants stated that familiarity also helped to make it easier to talk to colleagues, specifically, that familiarity enhanced the receptivity and empathy of the listener because there was more mutual understanding. Residents commented that they were more likely to share discussions and engage in debriefing after the referral-consultation process with more familiar colleagues.

Theme 2: Trust

Six unique subthemes, which we merged into the single theme of trust, emerged during analysis: (1) expertise, (2) reputation, (3) reliability, (4) alignment of interests, (5) engagement, and (6) personability and likability.

Expertise

The expertise and accuracy of the physicians (typically the referring physician) was a major theme identified in our analysis. Interestingly, consulting physicians were more likely to allow experts to use representative language to convey information (eg, describing a patient with a single word, such as “stable,” rather than asking for the particular vital signs). Nonexperts were described as being incorrect, being incoherent/inefficient, and requiring coaching. Nonexperts, on either side of the referral-consultation process, were required to provide more information.

Reputation

Reputation was often stated to be important in determining trust. As with any working environment, colleagues discuss performance and experiences with one another. Consulting residents noted that they often knew about untrustworthy EM attending physicians by reputation. Similarly, EM residents commented that bad reputations of consulting physicians affected their trust.

Reliability

Key dimensions under the theme of reliability included residents being helpful and consistent in their behavior (eg, practice patterns). For instance, participants described the phenomenon of having a good track record with a colleague. Residents valued colleagues that acted in predictable, dependable ways, such as being consistent in their description of patient status (eg, stability) and providing adequate support (eg, consulting physicians arriving to the ED promptly or emergency physicians stabilizing an unstable patient). A bad track record was described as past incidents when a resident colleague misrepresented the situation.

Alignment of Interests

Alignment of interests facilitated the consultation process, and a lack of common ground and shared interests created tensions. Participants discussed incidents in which they were skeptical about the other party's intentions and motivations. Skepticism led to mistrust. For instance, consulting residents commented frequently that EM physicians were “always leaving,” rushing to see other patients, or preferring to “dump” on consulting residents rather than transfer care of patients to their own EM colleagues. Participants perceived that more temporary physicians (off-service residents or locum tenens physicians) or “outsiders” lacked commitment and had poor intentions toward the system. Outsiders, such as EM physicians with temporary contracts or off-service rotating residents, were described as having little investment in or commitment to building relationships from the ED with other services and, therefore, were not trustworthy. As a counterpoint, having shared interests (ie, focusing on taking care of the patient) helped to develop a foundation for trust.

Engagement

Behaviors described as demonstrating the engagement of physicians were also described as increasing perceptions of their trustworthiness. Behaviors such as actively asking for feedback or progress reports on shared patients helped build relationships. Feedback and progress reports were only shared spontaneously from consulting physicians to emergency physicians if the consultants decided that there was a good (ie, safe, trusting) relationship.

Personability and Likability

Residents described being approachable, humble, personable, and sociable as important personal characteristics in establishing trust. Meanwhile, physicians who were rude, arrogant, standoffish, avoidant, obstructionist, or difficult were perceived as unlikeable. Residents reported that their actions deterred others from wanting to work with them (table 1). Consulting residents also commented that verbal thanks, or gestures such as sharing food or buying coffee, were appreciated and developed their trust of EM attending physicians because they thought these tokens were manifestations of collegial respect.

Discussion

Interpersonal relationships can affect communication processes in all environments. Our findings reaffirm that interpersonal attributes such as trust affect ED consultations. Multiple researchers have suggested that trust is important during the referral-consultation process.4,6 One important model for understanding trust is Giffin's Model of Interpersonal Trust, which originates from the social science literatures and focuses mainly on business interactions.22 The 6 factors of Giffin's model are listed in table 1, along with analogous themes from our study.22 Notably, Giffin's model serves to theoretically triangulate our findings, as the model aligns very well with our own subthemes of trust.

In the 1970s and 1980s , extensive work was done in social science fields around familiarity and trust17,23,24; however, recent work is mainly found in the business literature.25–28 Applications range from increased effectiveness with e-commerce to contractual choices.23,25–27

One of the main findings of our study was the link between familiarity and trust. In many ways, participants spoke of these 2 concepts concurrently. Multiple participants commented that being familiar with a colleague was almost synonymous with increased trust. An example of this is the following quote from an IM resident:

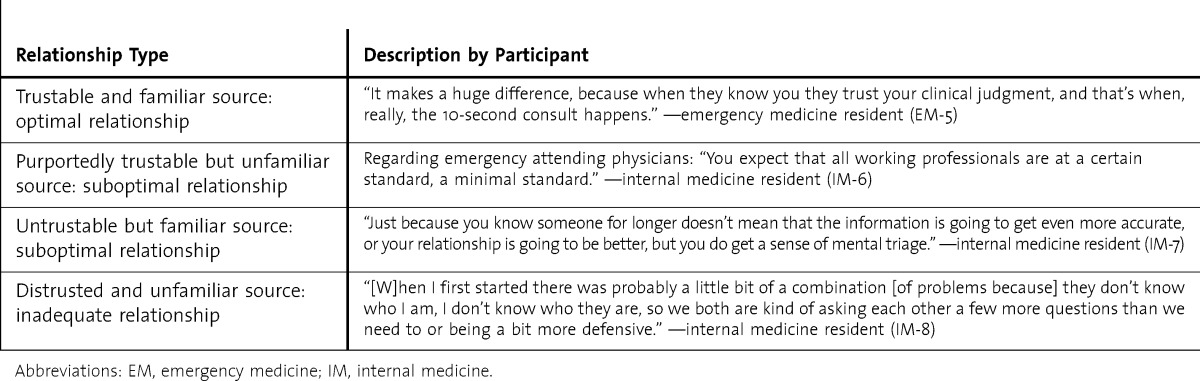

I find [trust and familiarity have] changed substantially from the beginning of my R2 year to the end of my R3 year…now they're very quick encounters and I get the information really quickly…we're usually on the same page, whereas when I first started there was probably a little bit of a combination [of problems because] they don't know who I am, I don't know who they are, so we both are kind of asking each other a few more questions than we need to or being a bit more defensive. But once you know the people it's very fast and you just go back and forth…You don't need a new set of vitals. They just said stable; I'm OK with that.

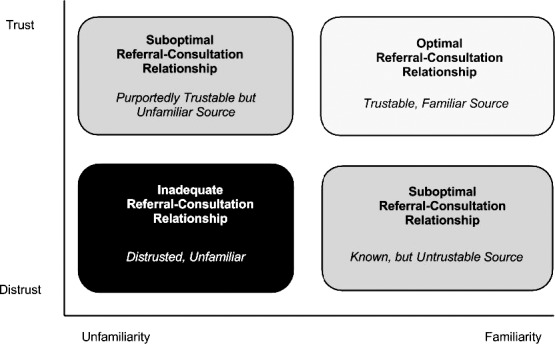

Part of this quote is shown in table 2, however, the depth of the quote in totality more fully describes the concurrent nature of familiarity and trust. In the typical academic teaching center there are implicit social structures and role definitions that may artificially generate trust or mistrust. For instance, by virtue of their role and relative expertness alone, an attending physician is trusted more than a medical student. Within the social dynamics of the referral-consultation process, trust and familiarity are related and create different relationships due to varying familiarity and trustworthiness. The 4 possible types of working relationships that develop are detailed in the Figure. Our model is meant to be a dynamic one; individuals may change over time in the way they regard a colleague or regard themselves. As learners gain familiarity with other physicians in the system, and as their trust is gained (eg, gain source credibility with seniority or prove track record over time), the learner will work toward a more optimal working relationship. table 2 shows example quotes that highlight the 4 proposed types of working relationships. Our model (Figure) is compatible with previous research including that of Luhmann, who distinguishes between and makes the link between familiarity and trust, stating that “trust has to be achieved within a familiar world, and changes may occur in the familiar features of the world which will have an impact on the possibility of developing trust in human relations.”24

FIGURE.

The Intersection Between Familiarity and Trust in the Referral-Consultation Process

TABLE 2.

Example Quotes for the 4 Types of Working Relationships

Our findings can provide a conceptual framework that may help us to better prepare junior learners. Social forces such as trust are known to be affected by source credibility,17 but once source credibility has been determined, learners may benefit from understanding how they can improve their own credibility and determine when they can trust others. Our findings complement recent work on standard approaches to ED consultations13,14; they also suggest a theoretical framework for interventions. By developing a nomenclature and framework for the elements of trust during the ED referral-consultation process, we might be able to develop methods to enhance the learners' experiences. Such interventions may include joint social activities to enhance familiarity or shared academic programming to enhance trust. Our findings may also serve as a theoretical foundation for the success of long-standing traditions such as off-service rotations, which have not had much empirical basis in the past. Further studies are required to develop measures to quantify familiarity and trust (as well as its subthemes) and determine how best to manipulate these outcomes for enhanced learner experience and patient care outcomes.

Our use of a single modality of data collection (semistructured focus group discussions) and the single-site setting limiting generalizability are the primary limitations of our study. In addition, the focus group moderator and lead investigator (T.C.) was an EM resident at the time of this project, which may have resulted in inadequate metaposition (ie, analytical distance from the subject matter). Finally, this study was completed as a planned subanalysis of the transcripts of a larger study regarding the ED referral-consultation process. Our analyses may have been affected by respondents' answers to other questions regarding mechanics and process, conflict, hierarchy, urgency, and institutional issues.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the ED referral-consultation experience may be substantially altered by the familiarity and perceived trustworthiness of parties involved. Our results provide an initial evidence-based conceptual framework for understanding the complexities of interphysician communications between referring and consulting physicians in the academic ED involving learners. Our framework may further inform instructional methods for improving the referral process between emergency and consulting physicians.

Footnotes

Teresa Chan, MD, is Clinical Scholar, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Kameron Sabir, MD, is Graduate of the St. James School of Medicine, Bonaire, Kralendijk, Netherlands Antilles; Sarila Sanhan, MD, is Graduate of the St. James School of Medicine, Bonaire, Kralendijk, Netherlands Antilles; and Jonathan Sherbino, MD, MEd, is Clinician Educator and Associate Professor, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, McMaster University.

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. The lead author was also the recipient of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada's Fellowship for Studies in Medical Education.

The data and analyses regarding this particular question about relationships and their effects on the referral-consultation encounter were previously presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physician's Conference as a poster in 2012 and at a local conference for the students at the University of Illinois at Chicago's Masters of Health Professionals Education program. Previous analyses for other aspects of the interview transcripts were previously presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians and the International Conference on Residency Education.

The authors would like to thank Gerson Mobo and Sarah Compeau for their assistance with the transcription process; Drs. John Crossley, Douglas Wright, and Claire Kenny-Scherber for their assistance in determining our study design and survey; Drs. Iman Ghaderi, Amy Corcoran, Bryan Judges, and Sean Moore for their commentary on the drafts of this document; and Dr. Ilene Harris for her advice and guidance in writing this article.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program Director Guide to the Common Program Requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/commonguide/CompleteGuide_v2%20.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons (Canada) Objectives of Training for Emergency Medicine. http://rcpsc.medical.org/information/index.php?specialty=122&submit=Select. Accessed December 6, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 1: critique of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 1991;37:2155–2161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muzin LJ. Understanding the process of medical referral: part 5: communication. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:301–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadhwa A, Lingard L. A qualitative study examining tensions in interdoctor telephone consultations. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):759–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant IN, Dixon AS. “Thank you for seeing this patient”: studying the quality of communication between physicians. Can Fam Physician. 1987;33:605–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaulieu MD, Samson L, Rocher G, Rioux M, Boucher L, Del Grande C. Investigating the barriers to teaching family physicians' and specialists' collaboration in the training environment: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woods RA, Lee R, Ospina MB, Blitz S, Lari H, Bullard MJ, et al. Consultation outcomes in the emergency department: exploring rates and complexity. CJEM. 2008;10(1):25–31. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500009970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews AL, Harvey CM, Schuster RJ, Durso FT. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 46th Annual Meeting. Vol. 2002. Baltimore, MD: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; Emergency physician to admitting physician handovers: an exploratory study; pp. 1511–1515. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortazzo JM, Guertler AT, Rice MM. Consultation and referral patterns from a teaching hospital emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11(5):456–459. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(93)90082-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee RS, Woods R, Bullard M, Holroyd BR, Rowe BH. Consultations in the emergency department: a systematic review of the literature. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(1):4–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.051631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright D, Kenny-Scherber C, Patel A, Kulasegaram K, Sherbino J. Defining and optimizing collaboration between emergency medicine and internal medicine physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;6(1):28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler C, Kutka BM, Badillo C. Consultation in the emergency department: a qualitative analysis and review. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan T, Orlich D, Kulasegaram K, Sherbino J. Understanding communication between emergency and consulting physicians: a qualitative study that describes and defines the essential elements of the emergency department consultation-referral process for the junior learner. CJEM. 2013;15(1):42–51. doi: 10.2310/8000.2012.120762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go S, Richards DM, Watson WA. Enhancing medical student consultation request skills in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(4):659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Board of Emergency Medicine. The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project. http://www.abem.org/public/docs/default-source/migrated-documents-and-files/emmilestonesmeeting4_final1092012.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed October 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method — 2007 Update With New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R. Creating effective learning in today's emergency departments: how accomplished teachers get it done. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraenkel JR, Wallen NE, editors. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. 6th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman GR, van der Vleuten CPM, Newble DI, editors. International Handbook of Research in Medical Education. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giffin K. The contribution of studies of source credibility to a theory of interpersonal trust in the communication process. Psychol Bull. 1967;68(2):104–120. doi: 10.1037/h0024833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JD, Weigert A. Trust as a social reality. Social Forces. 1985;63(4):967–985. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luhmann N. Familiarity, confidence, trust: problems and alternatives. In: Gambetta D, editor. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell Ltd; 1988. pp. 94–107. http://www.nuff.ox.ac.uk/People/backup/Gambetta/Other%20Papers/Trust_making%20and%20breaking%20cooperative%20relations.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gefen D. E-commerce: the role of familiarity and trust. Omega. 2000;28(6):725–737. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones GR, George JM. The experience and evolution of trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;23(3):531–546. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulati R. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Acad Manage J. 1995;38(1):85–112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohnet I, Zeckhauser R. Trust, risk and betrayal. J Econ Behav Organ. 2004;55:467–484. [Google Scholar]