Abstract

Background

Family-centered bedside rounds (family-centered rounds) enable learning and clinical care to occur simultaneously and offer benefits to patients, health care providers, and multiple levels of learners.

Objective

We used a qualitative approach to understand the dimensions of successful (ie, educationally positive) family-centered rounds from the perspective of attending physicians and residents.

Methods

We studied rounds in a tertiary academic hospital affiliated with the University of Calgary. Data were collected from 7 focus groups of pediatrics residents and attendings and were analyzed using grounded theory.

Results

Attending pediatricians and residents described rounds along a spectrum from successful and highly educational to unsuccessful and of low educational value. Perceptions of residents and attendings were influenced by how well the environment, educational priorities, and competing priorities were managed. Effectiveness of the manager was the core variable for successful rounds led by persons who could develop predictable rounds and minimize learner vulnerability.

Conclusions

Success of family-centered rounds in teaching settings depended on making the education and patient care aims of rounds explicit to residents and attending faculty. The role of the manager in leading rounds also needs to be made explicit.

What was known

Family-centered bedside rounds are beneficial to patients, health care providers, and learners.

What is new

A qualitative study examines perceptions of pediatrics residents and attending physicians regarding educationally effective family-centered rounds.

Limitations

Recall bias, small sample, and single-site study limit generalizability.

Bottom line

The effectiveness of family-centered rounds depends on the ability of attending physicians and senior residents to manage the educational setting, learning environment, and competing priorities.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article includes the questions (30KB, doc) used with the focus groups.

Introduction

Family-centered care is an important approach to planning, delivering, and evaluating pediatric health care based on a partnership among patients, families, and health care providers. Evidence has shown improved outcomes for patients and families, increased staff satisfaction, better cost-effectiveness, and benefits for pediatricians.1–5 A 2003 American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement advocated for attending physician rounds in the patients' room with the family present to help make a lasting impact on students and residents, particularly in teaching hospitals.6 Family-centered bedside rounds (family-centered rounds) are currently the most common rounding format used in North American pediatric hospitals.7 Recent work concluded that for patient- and family-centered care to be sustainable, it has to be a fundamental competency in resident education.8

Family-centered rounds are distinct from traditional bedside teaching in that encounters involve the patient's family, the attending, and a team of multi-level learners (medical students, residents). Clinical care and teaching take place simultaneously. If conducted with a clear understanding of the setting, goals, and teaching strategies, family-centered rounds permit explicit teaching of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists competencies.9,10 If not done effectively, there is a risk that learners will be led from room to room with little participation, minimal educational value, and poor efficiency.

Limited literature is available to guide teaching within a family-centered rounds environment.11–15 The setting is challenging as it requires attendings and senior residents to combine administrative, teaching, and clinical care roles in the presence of the patient and family. The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand the dimensions of successful family-centered rounds (ie, those that make it a positive educational experience) from the perspective of attending physicians and pediatrics residents.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted during 2009–2011 at the Alberta Children's Hospital, a tertiary-care academic hospital affiliated with the University of Calgary. The general inpatient clinical teaching unit (CTU) consisted of 2 teams assigned to 3 different inpatient units. Each team had an attending (lead), a senior resident, 2 or 3 junior residents, 2 medical students, and other health professionals (eg, nurses, pharmacists). The teams had turnover; attendings, medical students, and residents changed at 2-, 3-, and 4-week cycles, respectively. Teams were responsible for approximately 15 patients daily; census varied from 9 to 23. Most patients had complex medical conditions with multi-system and multi-specialty involvement.

Family-centered rounds were scheduled in the morning, and the patient's admission was reviewed at the bedside with the family present. Medical management decisions, resident and student teaching, and patient and family questions were addressed simultaneously.

Focus Groups

We used focus groups to collect data to understand attending and resident experiences and perceptions of educational success in family-centered rounds.16–18 Participants were CTU attendings and pediatrics residents. All attendings were eligible for participation. Residents were eligible if they had completed at least 1 CTU rotation. We sought participants for this study via e-mail and presentations at meetings.

Six initial focus groups were held: 2 each for junior residents, senior residents, and attendings to encourage free discussion. A seventh, final focus group, including a mix of junior and senior residents and attendings, was held to present theoretic constructs from the other focus groups and enable participants to comment on the credibility of the data based on their experience.16–18 Participation was voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw from the study at any point. All focus groups were conducted by A.K.S. with J.L. assisting.

Each focus group proceeded through a series of open-ended questions to explore perceptions about family-centered rounds (provided as online supplemental material). The focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed, and participant identities were hidden. Nvivo 7 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA) was used for coding and analysis. Data were analyzed using grounded theory and constant comparison methods.16–19

Data Collection

Open coding of data was undertaken with the first transcript, which was analyzed line by line. Researchers J.L. and A.K.S. independently coded transcripts from 2 focus groups and compared coding schemes to ensure consistency in the process. This process of coding proceeded in an iterative way through the transcripts from the other 4 focus groups. With each new focus group, the previous focus group transcripts were reexamined to ensure that coding was consistent. Once all transcripts were analyzed and the coding table was developed, K.M. and H.J.A. independently reviewed 1 transcript each to verify that the coding scheme was consistent and representative, and that thematic saturation had been achieved. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. Coding was adjusted throughout the process.

To identify emerging major themes, open-coding concepts were reorganized into broader, mutually exclusive categories. Subsequently, questions were asked about context and process to describe the relationships between and among the emerging major themes, a process known as axial coding.18 Lastly, a central category or core variable was identified to achieve theoretical integration.18

The approaches taken for data collection, analysis, and interpretation were designed for rigor, including “member checking” of the theory and constructs against participants' understanding during the seventh focus group as well as review of the literature on family-centered rounds to inform theory.16,18,20,21

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board.

Results

Twelve attendings, 10 senior residents, and 10 junior residents participated in the first 6 focus groups, and there were 4 to 6 participants per focus group. The attendings were Canadian graduates whose length of time in practice ranged from less than a year to 10 years, and all but 1 of the resident participants were Canadian graduates. Eighty percent (26 of 32) of the participants were women. The seventh focus group consisted of 2 attendings, 2 junior residents, and 2 senior residents. Focus groups lasted 90 to 120 minutes.

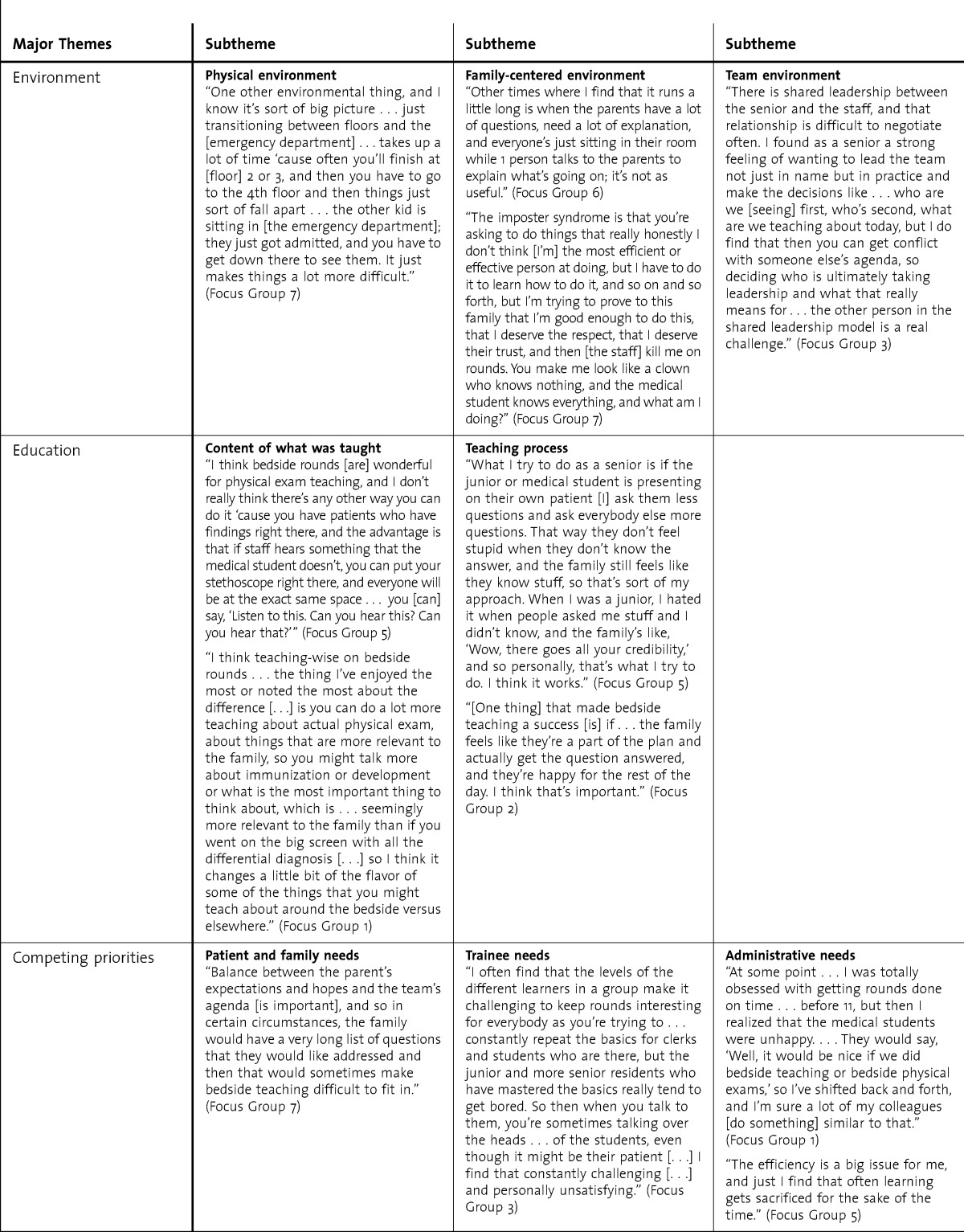

Three major themes reflecting the dimensions of the family-centered rounds experience emerged: (1) the environment, (2) education, and (3) competing priorities. An overview of these 3 themes, along with the subthemes and representative quotes, is presented in the table.

TABLE.

Dimensions of the Family-Centered Round Experience as Perceived by Pediatrics Attendings and Residents

Environment

The environment theme encompassed 3 subthemes: (1) physical environment, (2) family-centered environment, and (3) team environment (table).

Participants described the physical environment in which the rounds took place as a busy inpatient setting in which multiple factors may interfere with the process of rounds. Inadequate planning could make it challenging to maintain momentum and flow between patient rooms and could affect the time available and trainee enthusiasm for learning on rounds, particularly if equipment and supplies are not in place.

In the family-centered teaching environment, families are present and involved in the bedside teaching encounter, which sometimes leads to censoring of topics that could leave education unfinished from the residents' perspectives. In addition, the residents' role as care providers could be undermined if the family does not consider them to be full members of the care team. Lengthy conversations with families were perceived to be of low educational value and reduced time for other patients. Thus, family factors affected the flow of rounds, the type of teaching that took place, and the residents' role as physicians and care providers.

The family-centered rounds team environment referred to both the team that was providing patient care and the interactions among team members. Interactions between the various team members (ie, medical trainees, attending physicians, nurses, allied health professionals) contributed positively or negatively to the overall team environment and the experience. Rounds had a better pace and flow when the needs, expectations, and roles of each team member were considered. When senior residents and attendings did not use a compatible approach to leadership, rounds were often unpredictable, the specific educational needs of the different trainees were not addressed, and the rounds experience was perceived as unsuccessful.

Education

The education dimension of family-centered rounds had 2 subthemes: (1) the content of what was taught and (2) the teaching process (table).

The educational content of rounds was largely affected by the patient and the family. Participants described the content as being more psychosocial and family centered as opposed to medical, and participants noted that the rounds offered opportunities to learn communication, time management, and managerial skills. They also perceived the rounds to be an opportunity for physical examination teaching but reported that this did not occur often. They discussed the value of role modeling in shaping their education and indicated that family-centered rounds gave them an opportunity to know all the patients better than did conference room rounds.

Processes that contributed to learning included preparing and involving the family on rounds, mindful planning of the physical environment, and managing logistics to maximize efficiency and flow of rounds. Participants talked about the importance of explicit planning for family-centered rounds to ensure that sessions were focused, limited, inclusive, and sensitive to all learners. It was noted that members of the care team needed to be sensitive to the family while participating in the learning environment. Resident learning was undermined when the approach was inflexible, rounds lasted too long, patient numbers were high, and families were unprepared and unengaged. Other factors negatively contributing to the educational processes included teaching focused largely or exclusively on 1 group of learners, lengthy teaching sessions on topics irrelevant to the family, teaching that required note taking, conflicting approaches to patient management by attendings, and delivery of negative feedback to trainees in the presence of other colleagues and the family.

Competing Priorities

Competing priorities encompassed the subthemes of managing the diverse needs of patients, families, and trainees as well as administrative needs (table). Patient and family needs included patient care and patient safety considerations. Participants reported that families required laypeople's language, whereas trainees sought information and terminology that would enhance their medical expertise and success on examinations.

When too much attention was focused on a specific group, there was opportunity for conflict between the multiple types of learners involved in rounds, and attendings needed to balance opportunities for resident autonomy and team leadership with appropriate supervision. Administrative and patient demands also competed with education needs. For example, there was a need to ensure that patients were seen as efficiently as possible, yet maximizing team numbers and efficiency on rounds may take away from the time needed for teaching and providing feedback to learners.

The Manager Role

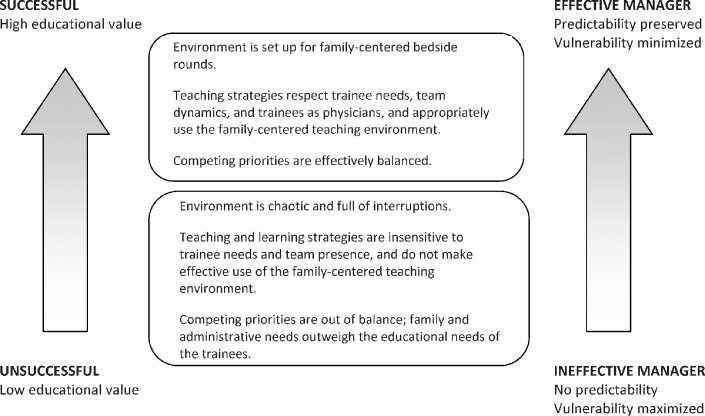

The experience of family-centered rounds ranged from successful and highly educational to unsuccessful and of low educational value (f i g u r e). The success of family-centered rounds depended on how well the environment, education, and competing priorities were managed, and predictability in the environment and empowerment of trainees were perceived as important components of the educational experience.

Leadership was critical to this process, and a positive experience during rounds was directly linked to the effectiveness of the manager. An effective manager was able to create this type of experience. This core variable also linked the data and the axial codes.

An effective manager was also able to balance the family-centered rounds environment and teaching strategies as well as manage competing priorities. This resulted in a clear understanding of the participants' respective roles on rounds and the schedule for the day, which enhanced the predictability and consistency of rounds. This gave trainees a sense of control.

In contrast, an unsuccessful experience had unpredictability in the environment, and the trainees felt extreme vulnerability. An ineffective manager was unable to mitigate the effects of these variables, resulting in a rounding experience that was perceived as unsuccessful and of low educational value.

Discussion

Attendings and pediatrics residents perceived their experience on family-centered rounds as a dynamic interplay between the physical environment, the education taking place in it, and the management of multiple competing priorities. A successful educational experience was directly linked to how well these factors were managed by the people leading the rounds.

Educational and organizational strategies that maximized predictability and minimized trainee vulnerability were critical to creating positive educational experiences. A strong manager was skilled at creating this type of environment. Effectiveness of the manager emerged as the core variable in this study, and managerial skills were essential for creating educationally effective rounds. Previous research has shown that family-centered rounds can improve the educational experience for trainees by demonstrating communication skills, confirming physical examination findings, and modeling bedside manner and medical professionalism.13,15,22,23 Studies also show that trainees perceive multiple barriers to effective rounds, including time management, lack of trainee autonomy, and too much focus on the family at the expense of trainees' teaching needs.13,15,23,24 Our results confirm these findings, and add environmental and logistical challenges to the list of factors that may impede success. The role of the attending physicians and senior residents in managing rounds emerged as the core variable, suggesting that the effectiveness of the manager is critical in educationally effective family-centered rounds. This is a novel finding not previously reported. In the complex CTU environment, effective management skills are critical for the quality of patient care and the quality of education for trainees.

Our study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single site, and most participants were women, though this was reflective of the population of trainees. Perceptions of family-centered rounds were based on participants' recall of their experiences, which may not be fully aligned with reality. There may have been unintended biases in data collection and analysis as the primary investigator (A.K.S.) is an attending on the pediatric CTU.

We identify several implications to enhance the role of the manager, optimize family-centered rounds as an ideal venue for teaching, and evaluate the manager's role. First, the role of the manager in leading the rounds needs to be made explicit. Providing evidence-based tips and strategies for leading educationally effective rounds and seeking evaluation from trainees based on these criteria would contribute to a better understanding of the importance of the manager role and would help program directors, clinical educators, and senior residents to become competent in this role. Regardless of the clinical setting, the skills of the manager as someone who ensures that care is delivered effectively and efficiently within a complex system is indispensible for physicians. Our findings also suggest a need for future research to confirm the central role of the manager in successful family-centered rounds. Expanding study participants to include medical students, nurses, and other allied health care professionals could offer added insight.

Conclusion

Grounded theory enabled us to conduct an in-depth study of the experiences of attending physicians and learners during family-centered rounds and to explore the relationship between environment, education, and competing priorities. It confirmed the central role that managing rounds has in creating an educationally effective experience for trainees. Our study points to a need to explicitly teach attendings and senior residents management skills to ensure that patient care and learning are optimized in this family-centered, bedside care environment.

FIGURE.

Spectrum of Educationally Effective Family-Centered Bedside Rounds

Footnotes

Amonpreet K. Sandhu, MD, MSc(Med Ed), FRCPC, is Hospital Pediatrician, Alberta Children's Hospital, and Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Calgary; Harish J. Amin, MBBS, MRCP(UK), FRCPC, FAAP, is Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary; Kevin McLaughlin, MB, ChB(Hons), MRCP, MSc, PhD, is Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, and Assistant Dean, Undergraduate Medical Education, University of Calgary; and Jocelyn Lockyer, PhD, is Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, and Senior Associate Dean of Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary.

Funding: This project was funded entirely by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Fellowship for Studies in Medical Education 2009.

The authors would like to thank the Alberta Children’s Hospital pediatricians and pediatrics residents for sharing their stories and experiences.

References

- 1.Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient-and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brousseau DC, Hoffman RG, Nattinger AB, Flores G, Zhang Y, Gorelick M. Quality of primary care and subsequent pediatric emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1131–1138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemmelgarn AL, Dukes D. Emergency culture and the emotional support component of family-centred care. Child Health Care. 2001;30(2):93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm KE, Patterson JM, Gurney JG. Parental involvement and family-centered care in the diagnostic and treatment phases of childhood cancer: results from a qualitative study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2003;20(6):301–313. doi: 10.1177/1043454203254984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson JL, Randall VF. Advancing a partnership: patients, families, and medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):191–197. doi: 10.1080/10401330701333787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Hospital Care, American Academy of Pediatrics. Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3, pt 1):691–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal VS, Sigrest T, Ottolini MC, Rauch D, Lin H, Kit B, et al. Family-centered rounds on pediatric wards: a PRIS network survey of US and Canadian hospitalists. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):37–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philbert I, Patow C, Cichon J. Incorporating patient- and family-centered care into resident education: approaches, benefits, and challenges. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):272–278. doi: 10.4300/JGME-03-02-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2013. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics; pp. e16–e17. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/320_pediatrics_07012013.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank JR, editor. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework: Better Standards. Better Physicians. Better Care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/resources/publications/framework_full_e.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chand DV. Observational study using the tools of Lean Six Sigma to improve the efficiency of the resident rounding process. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):144–150. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00116.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandler D, Snydman LK, Rencic J. Feedback based on observation of work rounds improves residents' self-reported teaching skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):374–377. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00206.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, Gonzalez del Ray J, DeWitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):829–832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen P, Stenger E, Bochkoris M, Hannon MJ, Kwoh CK. Family-centered multidisciplinary rounds enhance the team approach in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e603–e608. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox ED, Schumacher JB, Young HN, Evans MD, Moreno MA, Sigrest TD. Medical student outcomes after family-centered bedside rounds. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(5):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liamputtong P, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850–861. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiovitti RF, Piran N. Rigour and grounded theory research. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(4):427–435. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy TJ, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramani S, Orlander JD, Strunin L, Barber TW. Whither bedside teaching? A focus-group study of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(4):384–390. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200304000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landry MA, Lafrenaye S, Roy MC, Cyr C. A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference-room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):275–280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams KN, Ramani S, Fraser B, Orlander JD. Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):257–264. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]