Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Resident-Fellow Survey measurement of compliance with duty hours uses remote retrospective resident report, the accuracy of which has not been studied. We investigated residents' remote recall of 16-hour call-shift compliance and workload characteristics at 1 institution.

Methods

We sent daily surveys to second- and third-year internal medicine residents immediately after call shifts from July 2011 to June 2012 to assess compliance with 16-hour shift length and workload characteristics. In June 2012, we sent a survey with identical items to assess residents' retrospective perceptions of their call-shift compliance and workload characteristics over the preceding year. We used linear models to compare on-call data to residents' retrospective data.

Results

We received a survey response from residents after 497 of 648 call-shifts (77% response). The end-of-year perceptions survey was completed by 87 of 95 residents (92%). Compared with on-call data, the recollections of 5 (6%) residents were accurate; however, 48 (56%) underestimated and 33 (38%) overestimated compliance with the 16-hour shift length requirement. The average magnitude of under- and overestimation was 18% (95% confidence interval = 13–23). Using a greater than 10% absolute difference to define under- and overestimation, 39 (45%) respondents were found to be accurate, 27 (31%) underestimated compliance, and 20 (23%) overestimated compliance. Residents overestimated census size, long call admissions, and admissions after 5 pm.

Conclusions

Internal medicine residents' remote retrospective reporting of compliance with the 16-hour limit on continuous duty and workload characteristics was inaccurate compared with their immediate recall and included errors of underestimation and overestimation.

What was known

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education resident survey asks residents to retrospectively report on duty hour compliance.

What is new

Retrospective reporting of interns' compliance with the 16-hour limit on continuous duty was inaccurate when compared with recall immediately after the end of the continuous duty period.

Limitations

Single institution study reduces generalizability; nonanomymity of respondents may introduce social desirability bias.

Bottom line

Residents' retrospective reporting of compliance with continuous duty hours may overestimate or underestimate the incidence of violations.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (37.5KB, doc) used in this study.

Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) implemented duty hour standards to better balance “the needs of patient care, resident well-being, and education.”1–3 After implementation of the standards in 2003 and revision in 2011, numerous studies have evaluated their impact on patient safety, education, and fatigue, all resulting in systematic changes to achieve compliance based on survey data.4–11

Most evaluations of compliance rely on resident retrospective self-reports, and the accuracy of such reports has been questioned.4,12,13 The ACGME administers the Resident-Fellow Survey once per year between January and June; it requires residents to retrospectively answer questions on shift-length compliance and workload characteristics.14 Although several studies investigated the accuracy of resident self-report immediately after shifts,4,12,13,15 to our knowledge no studies have evaluated the accuracy of resident recall of their duty hour compliance over a longer period, similar to that of the ACGME survey. In this study, we examined the accuracy of residents' remote perceptions of shift-length compliance and workload characteristics.

Methods

Study Design

From July 2011 to June 2012, the Beth Israel Deaconess Internal Medicine Residency Program e-mailed a call-shift survey to second- and third-year general internal medicine residents after each 16-hour call shift (2 residents per day); the survey contained questions about hospital departure time and workload characteristics. In June 2012, the program e-mailed a survey to the same residents assessing perceptions of their 16-hour call shifts during the preceding year. Matched comparisons were performed between the on-call data and residents' retrospective perceptions of call shifts.

Call-Shift Survey

The call-shift survey, which had been used in a previous study, assessed team members' hospital departure time (departures beyond 11 pm indicated shifts exceeding 16 hours) and workload characteristics (number of patients on morning census, admissions accepted from night float, admissions accepted during the call shift, admissions accepted after 5 pm).10

Resident Perceptions Survey

We developed a retrospective survey to assess whether residents' remote retrospective perceptions of call shifts matched data about on-call activities (provided as online supplemental material). Residents estimated the percentage of time their team signed out by 11 pm during call shifts. We pilot tested and managed this survey through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). The Institutional Review Board approved the project.

Data Analysis

We compared call-shift characteristics to residents' retrospective perceptions of shift-length compliance and workload characteristics, excluding residents without data for either the call-shift survey (n = 1) or the perceptions survey (n = 8). We compared the percentage of time each resident's team signed out by 11 pm to the resident's retrospective perception of that percentage and calculated the difference between the 2 numbers. We defined underestimation as a negative value for the difference between the perceived and actual percentage of time each resident's team signed out by 11 pm; we defined overestimation as a positive value for this difference. Using these definitions, we reported the percentage of residents who under- and overestimated their time and determined the average degree of under- and overestimation using general linear models, weighted by the number of call-shift surveys per subject, where the resident was the unit of analysis. To estimate the rate of more extreme degrees of under- and overestimation, we recalculated the percentage of under- and overestimation using a more stringent definition, which required a greater than 10% absolute difference between the perceived and actual percentages before classifying the estimation as inaccurate.

To estimate the subject-specific differences between call-shift workload characteristics and retrospective perception of these characteristics, we used linear mixed-effects models of the subject-specific differences with an autoregressive correlation structure to account for within-subject correlation arising from multiple call-shift surveys per resident. We used the call shift as the unit of analysis for these workload characteristic comparisons. The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and Stata/IC-8 (StataCorp LP, College Park, TX).

Results

Call-Shift Data

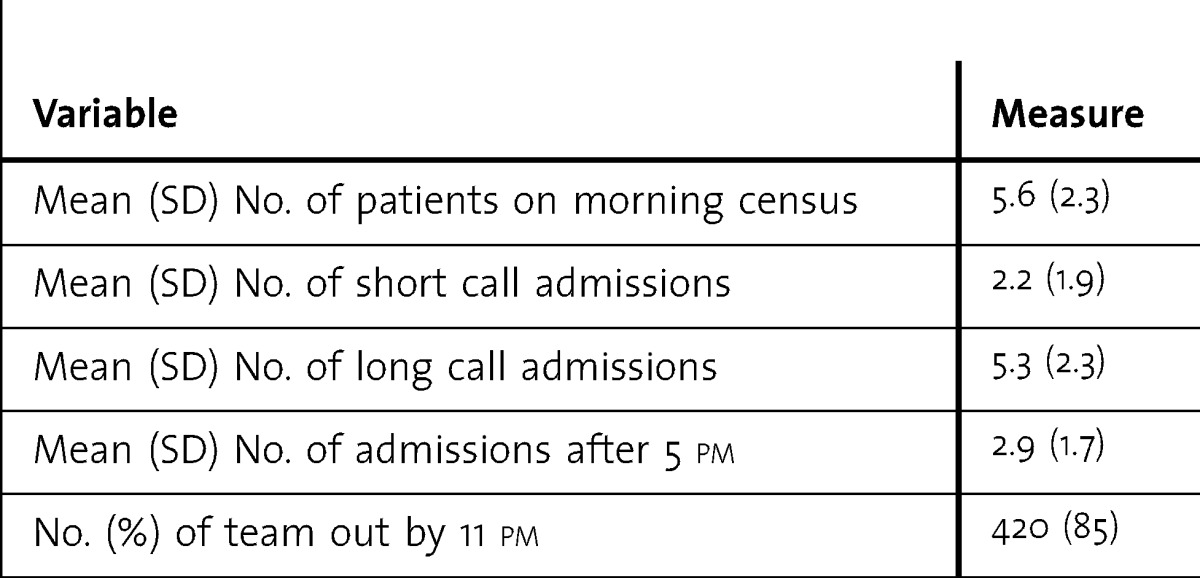

We received a survey response from residents after 497 of 648 call shifts during the study period (77% response), and in 77 responses (15%), at least 1 team member had an extended shift (departure after 11 pm). See Table 1 for call-shift workload characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medical Call Shifts During the 2011–2012 Year (N = 497)

Residents' Perceptions of Call Shifts

The end-of-year perceptions survey was completed by 87 of 95 residents (92% response). After excluding 1 resident with no call-shift data, the results indicated that 48 (56%) residents underestimated, 33 (38%) overestimated, and 5 (6%) were accurate in their estimation of the percentage of call shifts in which their team signed out by 11 pm. When using the more stringent definition of under- and overestimation, wherein we required a greater than 10% absolute difference between the estimated and actual percentages to classify an estimate as inaccurate in either direction, we found that 27 (31%) underestimated, 20 (23%) overestimated, and 39 (45%) were accurate in their estimation. The residents who underestimated, on average, estimated that they signed out by 11 pm 77% of the time compared with 95% of the time based on call-shift data, for an average underestimation of 18% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 13–23). The residents who overestimated, on average, estimated that they signed out by 11 pm 85% of the time compared with 67% of the time based on call-shift data, for an average overestimation of 18% (95% CI = 13–23). Compared with on-call data, residents' recall overestimated the average number of patients on a census before an admitting day, admissions accepted during the call shift, and admissions accepted after 5 pm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Call-Shift Characteristics and Residents' Retrospective Perceptions of Call-Shift Characteristics

Discussion

Residents' remote recall of 16-hour call-shift compliance and characteristics was not congruent with data obtained from actual shifts. Whether using a more or less stringent definition of accuracy, most residents either under- or overestimated compliance with shift length, and less than 50% were accurate in their recall. Additionally, residents overestimated the number of patients on the morning census, admissions accepted during the call shift, and admissions accepted after 5 pm. Our results raise questions about the accuracy of remote retrospective reporting of duty hour compliance and workload characteristics.

Several studies have investigated the accuracy of resident self-report of duty hours compared with more objective standards, including electronic time-card swipes, electronic health record activity, electronic parking garage swipes, and daily resident surveys, all with mixed results; some suggest overreporting of duty hour violations when reported remotely.4,12,13,15 None of these studies assessed recall of shifts at a time more remote than 2 weeks. We believe our study design represents a pragmatic investigation into the accuracy (or inaccuracy) of residents' remote recall in a manner similar to the ACGME method. In addition to the obvious regulatory and financial consequences of duty hour violations, workload assessment by residents contributes significantly to the annual program review performed by educators and informs decisions about staffing models and admitting structure change. Program directors and administrators will need to consider the potential inaccuracy of their workload information when making such changes.

Our residents overestimated the number of patients on their morning census, admissions accepted during call shifts, and admissions accepted after 5 pm. To our knowledge, no studies have specifically investigated the accuracy of resident perceptions of such workload characteristics. Although these were only small overestimations, ranging from an absolute difference of 0.4 to 1.3 patients, given the low overall numbers of admissions, these differences represent a nontrivial proportion of overall admissions. Although the practical implications of these findings in our program are uncertain given that our overall census and admission numbers are well below the Residency Review Committee for Internal Medicine workload standards, these observed inaccuracies in recall may be more important in a program where patient numbers approach the maximum allowable limits. Our findings suggest that questions aimed at assessing compliance with workload features yield similarly inaccurate responses when asked remotely.

The study has several limitations. First, data were collected at a single institution and may not be generalizable. Second, because the surveys identified respondents, the data are prone to social desirability and recall bias. We specifically chose retrospective survey instrument items that paralleled call-day survey items to allow for direct, numeric comparisons. However, because we did not use categorical responses, such as those used in the ACGME survey (eg, “very often,” “often”) or create a scale to translate resident response values to the ACGME response categories, we cannot comment directly on the accuracy of residents recall as it pertains to the ACGME survey. Additionally, although we used the call-day survey in a prior study, we have not assessed the construct validity of the instrument. Finally, although our study suggests inaccuracy of delayed self-report, the accuracy of immediate self-report has also been questioned.4,12,13,15

Conclusion

Compared with data recorded immediately after 16-hour call shifts, residents were inaccurate in their remote estimation of duty hour compliance and overestimated workload characteristics. Given the importance of accurate duty hour reporting for targeting changes to admitting structures, measuring the effect of those changes, and maintaining accreditation for residency programs, further work should investigate alternatives to remote recall surveys for duty hour assessment.

Footnotes

Jed D. Gonzalo, MD, MSc, is Assistant Professor of Medicine at Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine; Julius J. Yang, MD, PhD, is Director of Inpatient Quality, Silverman Institute for Healthcare Quality and Safety at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School; Long Ngo, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Alicia Clark, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine; Eileen E. Reynolds, MD, is Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School; and Shoshana J. Herzig, MD, MPH, is Instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The authors would like to thank the internal medicine residents at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for their participation.

References

- 1.Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT. ACGME Work Group on Resident Duty Hours. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1112–1114. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein EB, Savel RH, Chorost MI, Borgen PI, Cunningham J. Use of text messaging to enhance compliance with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education resident duty hour requirements. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(6):379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME, editors. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedule to Improve Patient Safety, Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shine D, Pearlman E, Watkins B. Measuring resident hours by tracking interactions with the computerized record. Am J Med. 2010;123(3):286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora VM, Georgitis E, Siddique J, Vekhter B, Woodruff JN, Humphrey HJ, et al. Association of workload of on-call medical interns with on-call sleep duration, shift duration, and participation in educational activities. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1146–1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landrigan CP, Fahrenkopf AM, Lewin D, Sharek PJ, Barger LK, Eisner M, et al. Effects of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour limits on sleep, work hours, and safety. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):250–258. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Even-Shoshan O, Canamucio A, et al. Mortality among patients in VA hospitals in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):984–992. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, Even-Shoshan O, Wang Y, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975–983. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1838–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalo J, Herzig S, Reynolds E, Yang J. Factors associated with non-compliance during 16-hour long call shifts. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1424–1431. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCoy CP, Halvorsen AJ, Loftus CG, McDonald FS, Oxentenko AS. Effect of 16-hour duty periods on patient care and resident education. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(3):192–196. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd SR, Fahy BN, Paukert JL, Mersinger D, Johnson ML, Bass BL. How accurate are self-reported resident duty hours. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(2):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saunders DL, Kehoe KC, Rinehart VH, Berg BW. Self-reporting of internal medicine house staff work hours. Hawaii Med J. 2005;64(1):14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Collection Systems: Resident-Fellow Survey. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/DataCollectionSystems/ResidentFellowSurvey.aspx. Accessed January 28, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chadaga SR, Keniston A, Casey D, Albert RK. Correlation between self-reported resident duty hours and time-stamped parking data. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):254–256. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00142.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]