Abstract

Background

The outpatient continuity clinic is an essential component of internal medicine residency programs, yet continuity of patient care in these clinics is suboptimal. Reasons for this discontinuity have been inadequately explored.

Objective

We sought to assess perceived factors contributing to discontinuity in trainee ambulatory clinics.

Methods

The study encompassed 112 internal medicine residents at a large academic medical center in the Midwest. We conducted 2 hours of facilitated discussion with 18 small groups of residents. Residents were asked to reflect on factors that pose barriers to continuity in their ambulatory practice and potential mechanisms to reduce these barriers. Resident comments were transcribed and inductive analysis was performed to develop themes. We used these themes to derive recommendations for improving continuity of care in a resident ambulatory clinic.

Results

Key themes included an imbalance of clinic scheduling that favors access for patients with acute symptoms over continuity, clinic triage scripts that deemphasize continuity, inadequate communication among residents and faculty regarding shared patients, residents' inefficient use of nonphysician care resources, and a lack of shared values between patients and providers regarding continuity of care.

Conclusions

The results offer important information that may be applied in iterative program changes to enhance continuity of care in resident clinics.

What was known

Internal medicine continuity experiences are used to teach residents about continuity, but continuity of care is suboptimal in these clinics.

What is new

A study explored discontinuity in resident clinics by assessing resident perceptions of causes.

Limitations

Study was limited to resident perceptions and could not prioritize the relative contribution of each factor; single institution study limits generalizability.

Bottom line

Recommendations include scheduling to optimize the ratio of acute and follow-up visits, establishing triage that prioritizes continuity patients, promoting enhanced communication about shared continuity patients, incorporating effective use of nonphysician care resources, and educating patients about the benefits of continuity.

Introduction

Continuity of patient care in the primary care setting has both implicit and explicit value. Recognized as a key mechanism for improved quality of care,1 enhanced continuity is associated with improved patient and provider satisfaction, improved adherence to recommended preventive care, and decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.2–4

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements for internal medicine programs recognize the importance of continuity experiences for residents, noting that ambulatory education “must include a longitudinal continuity experience in which residents develop a continuous, long-term therapeutic relationship with a panel of general internal medicine patients.”5 Despite this charge, achieving continuity of care in teaching settings remains challenging. Continuity is lower in resident continuity clinics compared with private practice settings,6 and the finite duration of training inherently limits residents' continuous relationship with their ambulatory patients. Previous studies have demonstrated that added clinic time is associated with enhanced continuity,7,8 and innovative education models that extend continuity clinics throughout residency to target these longitudinal relationships may enhance continuity.9

Resident physicians value continuity relationships with their patients and feel challenged by the lack of continuity of care,4 yet there has been little study of resident perceptions of barriers to continuity and systemic solutions to discontinuity. As key stakeholders in their own continuity clinic experience, resident physicians are uniquely poised to inform the debate on the issue of discontinuity in their practice. We present a qualitative analysis of internal medicine residents' perspectives on factors contributing to discontinuity in ambulatory clinics and potential mechanisms to attenuate these factors.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in the Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Residency Program, a large academic residency in the Midwest. Throughout the 3 years of training, resident physicians participate in a continuity clinic practice where they provide longitudinal care to their own panel of patients. All residents have 50% outpatient and 50% inpatient experiences throughout their training scheduled in alternating 1-month blocks with twice-weekly continuity clinic during outpatient months and no clinic during inpatient months. Residents work in care teams of 6 resident providers (2 providers from each postgraduate year) who care for each other's outpatients for acute issues when the primary resident physician is not in the clinic. There are 4 resident care teams per firm, and each firm is overseen by a faculty firm chief. The 6 firms are housed in different clinic sites: 4 firms provide primary care to a panel of patients in the institution's home county and 2 provide continuity care to patients from surrounding regional counties. Patients are assigned to their resident physician only, and there is a pool of 8 supervising faculty in each firm. Most of the resident care teams and firms are further embedded in a patient-centered medical home, characterized by the allied health staff and systems built for coordinated primary care delivery.

One component of the continuity clinic curriculum includes semiannual in-depth review of a topic relevant to the outpatient practice of medicine (eg, outpatient diabetes management, colorectal cancer screening). These sessions take the place of clinic for a half day; they are facilitated by each firm chief and include all available residents in every firm. The sessions are designed to highlight the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies of practice-based learning and improvement, where residents reflect on their own practice (eg, their own diabetes quality measures), and systems-based practice, where residents reflect on opportunities to systematically improve care in their practice (eg, diabetes quality measures for the practice).10

Based on reports of resident dissatisfaction with discontinuity in their practices, continuity of care was a topic of in-depth sessions conducted in March and April 2011. The session started with case-based reflections on the importance of continuity and longitudinal relationships with patients on their practice. Residents then spent approximately 30 minutes conducting a chart audit on a random sample of 20 patients from their panels. During this practice-based learning and improvement exercise, residents calculated continuity statistics for their panel from the provider and patient standpoint.6,11 Both values were approximately 50% (half of patient visits are with the provider's own patients and half of patient visits are with their own provider). For instances of discontinuity, residents reflected on potential reasons for the lack of continuity. After this exercise, groups came together to systematically reflect on barriers to continuity in the resident practice and opportunities for improvement. The methodology and results stemming from this root cause analysis of factors contributing to discontinuity from the resident perspective are the focus of this article.

Root Cause Analysis of Factors Contributing to Discontinuity

Two hours of facilitated discussion occurred among 18 distinct small groups of residents (6 to 7 residents per session). The first discussion item asked residents to reflect on all potential factors contributing to discontinuity in their practice. The second discussion item asked residents to reflect on opportunities and mechanisms to attenuate each of these barriers. Residents at the Mayo Clinic are trained in principles of quality improvement as a longitudinal component of their curriculum12; they applied principles of the root cause analysis learned in that curriculum to this discussion of continuity, including cause-and-effect diagrams, the “5 whys,” and mind maps. Each session was facilitated by a faculty firm chief.

Qualitative Data Analysis

At each of the 18 discussions, a faculty firm chief took notes during the root cause analysis exercise. From the discussion, concepts were recorded that addressed factors contributing to discontinuity in the resident practice and opportunities and mechanisms to improve continuity. As residents presented their ideas, the note-taking faculty firm chief could probe for meaning as appropriate. After all 18 sessions had been conducted, each of the 6 participating faculty firm chiefs transcribed notes from the 3 sessions he or she had facilitated. Through inductive analysis of these transcripts, each firm chief derived themes as coding units for his or her 3 sessions.13 Themes from each firm chief were collected and collated by a single firm chief. These collated themes were then sent back to the other firm chiefs, and their content and meaning were debated at a meeting from which a final list of themes was derived.

Each firm chief then organized the theme list into meaningful, generalizable categories; each category contained 1 or more of the established themes. The content of the collated categories was reviewed and modified during two 1-hour meetings among the 6 firm chiefs until consensus was achieved. Firm chiefs then developed recommendations for improving continuity of care in the residency ambulatory clinic in an additional 1-hour meeting. The firm chiefs' inductive analysis and category formation was further informed by their own contextual knowledge of issues contributing to discontinuity gained from their roles as clinical preceptors and institutional leaders for internal medicine outpatient graduate medical education.

Results

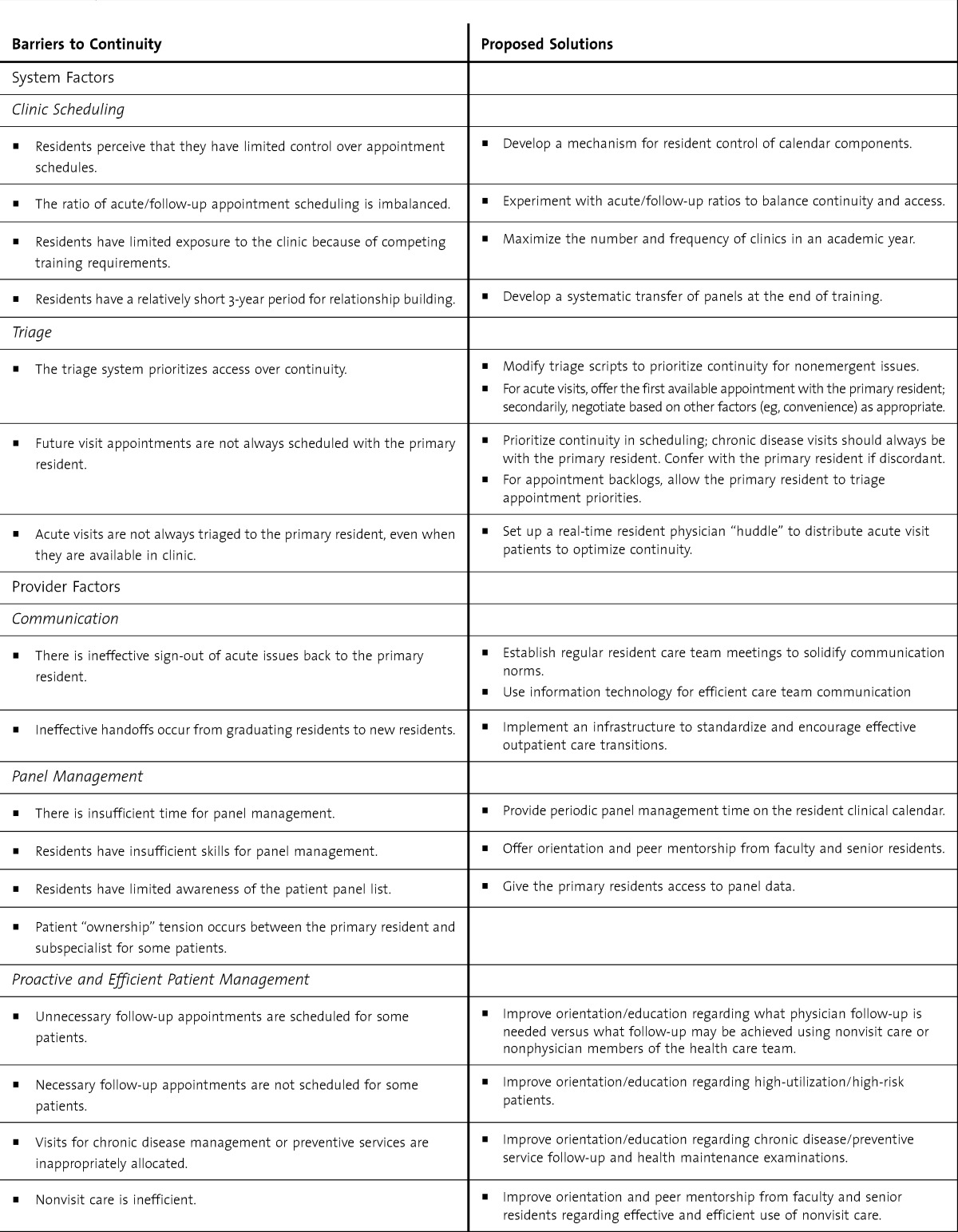

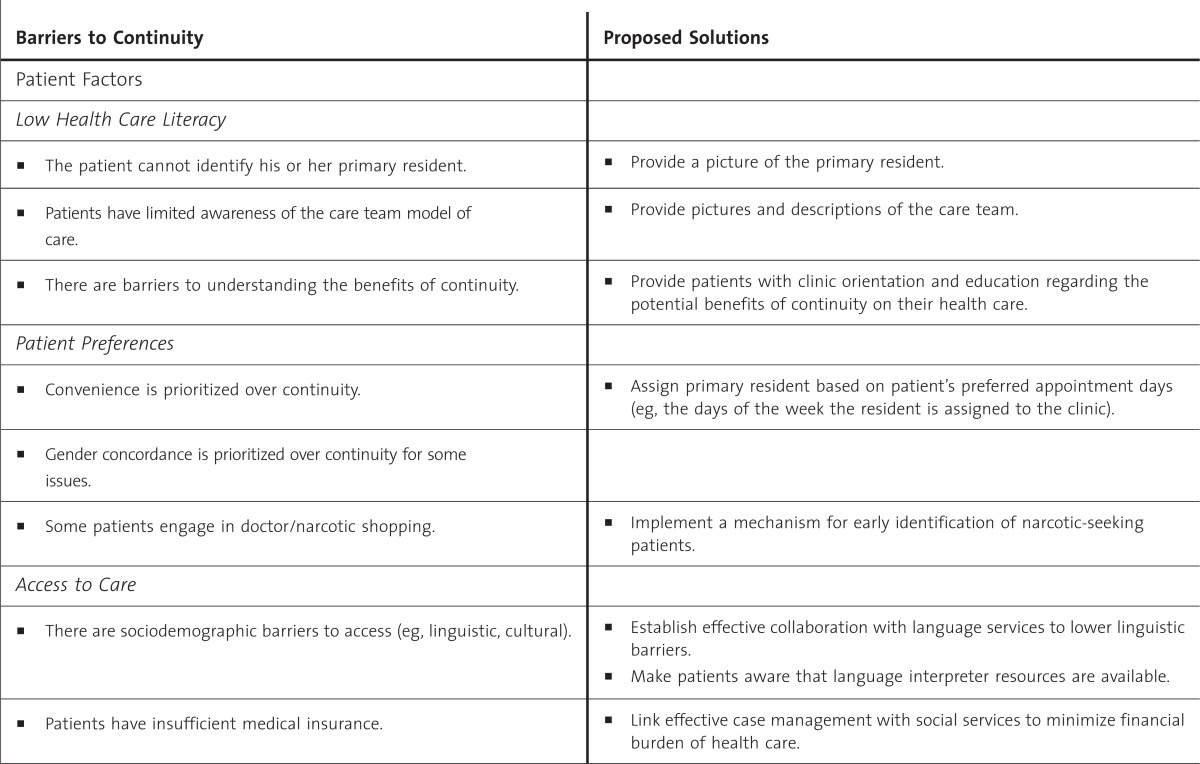

Seventy-eight percent (112 of 143) of all program residents participated in facilitated discussions of factors contributing to discontinuity in their clinics; absences were because of vacations, trips, and so on. Categories and themes for system, provider, and patient barriers to continuity of care and proposed solutions for the residency ambulatory clinic are shown in the table. Key themes included an imbalance of clinic scheduling, which favors acute access over continuity; clinic triage scripts delivered by patient appointment clinical assistants that deemphasize continuity; inadequate communication among providers regarding shared patients; inefficient use of nonphysician care resources among trainees; and suboptimal shared values between patients and providers regarding continuity of care. Recommendations for improving continuity of care in the residency ambulatory clinic are shown in the box.

TABLE.

Barriers to Continuity of Care and Proposed Solutions for the Residency Ambulatory Clinic

Box Recommendations for Improving Continuity of Care in a Residency Ambulatory Clinic

Adapt clinic schedules to maximize clinic days and optimize the ratio of acute to follow-up visits to balance access and continuity.

Adjust clinic appointment triage protocols to prioritize continuity.

Implement communication mechanisms to facilitate provider-to-provider communication regarding shared patients.

Teach and model effective use of interdisciplinary teams for improved panel management.

Educate patients about the value of ambulatory care teams and patient-centered medical homes toward the goal of longitudinal relationships and continuity of care.

TABLE.

Continued

Discussion

The intermittent nature of resident clinic limits the residents' presence in clinic and, by default, negatively affects residents' availability to provide continuity of care for their ambulatory patients. Residents recognized that their limited clinic hours as a systematic barrier to continuity of care. Residents also recognized that careful and sustained attention to the ratio of acute to follow-up appointment slots is an important systematic predictor of continuity. A schedule template that emphasizes acute appointment slots will compromise continuity, while a drift toward too many follow-up appointment slots will compromise access.14,15 The optimal template may also shift over time with changes in the practice and patient populations. Therefore, our first recommendation is to institute a review and ongoing adjustment of the clinical calendar to optimize appointments for both continuity care and acute access visits. In addition, resident panels need to be carefully managed to ensure appropriate panel size and case mix, which also influence access and continuity of care.7,16

Suboptimal appointment triage systems were also identified as a barrier to continuity of care. Because of less frequent access and less longitudinal relationship-building time with their patients, the continuity metrics of a resident practice may be particularly vulnerable to inconsistent or nonstandardized triage scripts. Residents perceived that triage systems prioritized appointment access over continuity, and patients with nonurgent complaints were triaged to a same-day appointment with a different provider rather than a later appointment with their primary care physician. To some degree, this likely reflects patient preference, yet it highlights the opportunity to develop more consistent scripts for appointment schedulers. We recommend that scripts emphasize appointments with the patient's primary resident for nonemergent issues, chronic disease management, and preventive care.

Communication gaps between residents caring for ambulatory patients also created barriers to continuity. Continuity of information is described as an essential element of continuity of care.17 A study assessing outcomes of discontinuity demonstrated that primary care provider discontinuities are associated with more negative care experiences, irrespective of whether discontinuities involve visits within or outside of the ambulatory team.18 This discontinuity of information may be especially relevant for the resident clinics, where lack of communication between the primary continuity resident and the provider for the patient's acute visit may result in unresolved clinical issues and a failure to bring the illness episode back into the purview of care by the primary resident. Although there has been emphatic curricular and programmatic focus on inpatient handoffs in graduate medical education, ambulatory handoffs have not received the same degree of attention,19 and our third recommendation is to implement communication mechanisms to facilitate provider-to-provider communication regarding shared patients.

Residents identified lack of education in panel management as another barrier to continuity. Deciding which patients need physician follow-up, which can be managed effectively and safely through nonvisit means of care (eg, telephone or e-mail), and which can be seen in follow-up by nurses or other members of the health care team is a skill. This skill is important in preserving limited appointment slots for patients who truly need direct physician care, which may promote panel continuity. The ability to work effectively in interdisciplinary health care teams is essential for effective outpatient care in a patient-centered medical home that allows each team member to function to their maximum capability in support of timely, continuous, coordinated, and patient-centered care.20,21 Therefore, our fourth recommendation for improved continuity is to teach and model effective use of interdisciplinary teams and nonphysician care for improved panel management.

Residents also identified 2 separate patient-related factors that may negatively affect continuity of care. They noted that continuity was more likely to be compromised for patients with low health literacy, non–English-speaking patients, and patients with intermittent lapses in health insurance. National data show that the socioeconomic position of patients seen in resident clinics is lower than in analogous faculty practices,22–24 and it is important to ensure that clinic support for these patients is optimized.25 Multidisciplinary health care teams that include resident physicians should ensure that equal or increased resources are allocated to the resident practice compared with the faculty practice to help manage sociodemographic barriers to effective care among resident patients. Further, education regarding the care of vulnerable populations and role modeling by faculty should permeate the ambulatory experience,26 particularly in the context of limited resident knowledge about factors affecting the health status of underserved populations.27

The second set of patient-related factors identified by residents revolved around the perspective that continuity of care is often not given a high priority by the patients themselves. Patient preferences may affect the patient's commitment to a continuity relationship and may, in turn, affect clinic utilization patterns, influencing whether a patient chooses to wait to see his or her personal physician or seek care from another available provider.28,29 Patients conditioned to seeing several different resident providers may not see the value in continuity of care or appreciate models of team-based care. Thus, we recommend patient education regarding the concept of the patient-centered medical home and the aims of longitudinal relationships and continuity of care centered on patients' personal health care needs and preferences.

Limitations of our study include, first, the fact that qualitative inquiry cannot quantify the relative contributions of barriers we identified to continuity, and we are not able to prioritize the recommended interventions. Second, residents represent 1 stakeholders group in assessing continuity barriers. Future work should focus on triangulation of our results with the perspectives of patients, faculty preceptors, and other health care professionals. Third, bias may be introduced by the role of the firm chiefs in the analysis; this may also have influenced the residents' responses. Finally, the study was conducted at a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of our observations.

Conclusion

Continuity of care is important for patient care and education in the ambulatory setting, and these results offer new insights from the residents' perspective on barriers and potential solutions to discontinuity. Our findings augment and extend existing knowledge of factors contributing to discontinuity in resident clinics, and the recommendations formulated may be applied toward iterative programmatic changes to enhance continuity of care in resident clinics.

Footnotes

All authors are at the Mayo Clinic. Mark L. Wieland, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine; Thomas M. Jaeger, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine; John B. Bundrick, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of General Internal Medicine; Karen F. Mauck, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of General Internal Medicine; Jason A. Post, MD, is Instructor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine; Matthew R. Thomas, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine; and Kris G. Thomas, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine, and Consultant, Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine.

Funding: This article was supported in part by the Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Residency Office of Educational Innovations as part of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Educational Innovations Project.

The views expressed by the authors are their own and should not be considered policy statements of any organizations with which any of the authors may be affiliated.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(12):974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez HP, Rogers WH, Marshall RE, Safran DG. The effects of primary care physician visit continuity on patients' experiences with care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):787–793. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delva D, Kerr J, Schultz K. Continuity of care: differing conceptions and values. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(8):915–921. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in internal medicine. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/140_internal_medicine_07012013.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darden PM, Ector W, Moran C, Quattlebaum TG. Comparison of continuity in a resident versus private practice. Pediatrics. 2001;108(6):1263–1268. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis MD, Zahnd WE, Varney A, Scaife SL, Francis ML. Effect of number of clinics and panel size on patient continuity for medical residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):310–315. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBurney PG, Moran CM, Ector WL, Quattlebaum TG, Darden PM. Time in continuity clinic as a predictor of continuity of care for pediatric residents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):1023–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0280-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warm EJ, Schauer DP, Diers T, Mathis BR, Neirouz Y, Boex JR, et al. The ambulatory long-block: an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) educational innovations project (EIP) J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):921–926. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Outcome project: key considerations for selecting assessment instruments and implementing assessment systems. https://dconnect.acgme.org/outcome/assess/keyconsids.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N, Reeb KG. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J Med Educ. 1975;50:965–969. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leenstra JL, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Mundell WC, Thomas KG, Krajicek BJ, et al. Validation of a method for assessing resident physicians' quality improvement proposals. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1330–1334. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0260-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balasubramanian H, Banerjee R, Denton B, Naessens J, Stahl J. Improving clinical access and continuity through physician panel redesign. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1109–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose KD, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1150–1159. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan K, Brown SR. Decreased continuity in a residency clinic: a consequence of open access scheduling. Fam Med. 2009;41(1):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez HP, Rogers WH, Marshall RE, Safran DG. Multidisciplinary primary care teams: effects on the quality of clinician-patient interactions and organizational features of care. Med Care. 2007;45(1):19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241041.53804.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchanan IM, Besdine RW. A systematic review of curricular interventions teaching transitional care to physicians-in-training and physicians. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):628–639. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318212e36c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sevin C, Moore G, Shepherd J, Jacobs T, Hupke C. Transforming care teams to provide the best possible patient-centered, collaborative care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2009;32(1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000343121.07844.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brook RH, Fink A, Kosecoff J, Linn LS, Watson WE, Davies AR, et al. Educating physicians and treating patients in the ambulatory setting. Where are we going and how will we know when we arrive. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(3):392–398. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serwint JR, Thoma KA, Dabrow SM, Hunt LE, Barratt MS, Shope TR, et al. Comparing patients seen in pediatric resident continuity clinics and national ambulatory medical care survey practices: a study from the continuity research network. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e849–e858. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancy WS, Jr, Macpherson DS, Hanusa BH, Switzer GE, Arnold RM, Buranosky RA, et al. Patient satisfaction in resident and attending ambulatory care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.91005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keirns CC, Bosk CL. Perspective: the unintended consequences of training residents in dysfunctional outpatient settings. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):498–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816be3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wieland ML, Beckman TJ, Cha SS, Beebe TJ, McDonald FS Underserved Care Curriculum Collaborative. Resident physicians' knowledge of underserved patients: a multi-institutional survey. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):728–733. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira AG, Pearson SD. Patient attitudes toward continuity of care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(8):909–912. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Love MM, Mainous AG., III Commitment to a regular physician: how long will patients wait to see their own physician for acute illness. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(3):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]