Abstract

Purpose

The Myelopathy Disability Index and the Neck Disability Index are widely used to assess outcome in cervical spine surgery. Short Form (SF) 36 is a generic measure of health which can be used to measure health gains across a wide variety of conditions. The aim of the current study is to assess long-term outcomes using these measures in a cohort of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM).

Methods

Cohort study with prospective data collection. Patients with CSM being offered decompressive surgery were asked to complete a set of generic and condition-specific outcome measures. This was repeated post-operatively at 3, 12, 24 and 60 months. SF-36 was used as a generic outcome measure and the Myelopathy Index, Neck Disability Score and visual analogue scores for arm, neck and hand pain, paraesthesia and dysthaesia were used as condition-specific outcome measures.

Results

Significant improvements in all outcome measures were seen in 70 % of the cohort. For SF-36, pre-operative scores were lower than age-matched controls in all domains and significant improvements were seen 3 months following surgery. This improvement in outcome was maintained at 5 years follow-up in approximately two-thirds of those with initial improvement.

Conclusion

We have used generic and condition-specific outcome measures of health and shown that in patients with CSM treated surgically, up to 70 % can expect improvement in their quality of life. These outcome measures are easy to collect and provide objective evidence of changes in quality of life and disability and can help quantify the potential health gains that can be achieved.

Keywords: Cervical myelopathy, Disability outcome, Short Form 36, Visual analogue score

Introduction

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a degenerative condition of the spine, which results in compression of the spinal cord. Surgical decompression is considered to be the best means of halting disease progression. Assessment of outcome is often made difficult by confounding factors and lack of objective outcome measurements. Some patients improve following surgery, some are unchanged and others continue to get worse [1]. Both generic and condition-specific outcome measures have been developed to assess the benefits of surgery. Outcome measures have been defined as any measurement system used to uncover or identify the health outcome of treatment for the patient [2]. Important characteristics of outcomes include physical and emotional dimensions of health and objective and subjective events such as death and alleviation of pain [3]. Outcome measures aim to be objective, reproducible and responsive to changes in clinical condition. Validity is often gauged by associations with different, but related measures in a predictable direction and of a proportionate magnitude [4].

We have previously reported outcome following surgical decompression in seventy patients with CSM [4]. We used the Short Form (SF) 36. Scores obtained pre-operatively and at 3 and 12 months post-operatively were recorded and we were able to show that this generic measure of outcome is responsive, valid and practical in CSM. In this study, our objective is to apply both generic and condition-specific outcome measures to assess outcome in a larger cohort of patients following surgical decompression in CSM as well as to collect long-term outcome where available.

Materials and methods

Patients undergoing surgery are entered prospectively onto a personal computerised registry. All patients with CSM under the care of the senior author (RJL), in whom the decision to offer surgical decompression was made, were asked to complete a questionnaire of generic and condition-specific outcome measures pre-operatively. This was repeated at 3, 12, 24 and 60 months post-operatively. Data from these outcome measures were entered prospectively into a second outcomes register by an audit clerk who works independently from the surgical team. Generic outcome measures were the SF-36 and visual analogue scores for arm, neck and hand pain, paraesthesia and dysthaesia. Condition-specific outcome measures were the Myelopathy Index and the Neck Disability Score. Outcome scores are ordinate and non-parametric. Scores were compared for each patient using the Wilcoxin’s matched pairs signed ranks test. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.

All patients all had symptoms compatible with CSM and cervical spinal cord compression was demonstrated on MRI scan. The majority of patients had dominant anterior compression, which was treated with anterior cervical decompression at single or multiple levels. Only seven anterior decompressions were instrumented. Elderly patients with multiple level compression and preserved lordosis underwent cervical laminectomy. Younger patients with canal stenosis were offered laminectomy with postero-lateral instrumented fusion or cervical laminoplasty.

Results

Pre-operative and 3 month post-operative outcome measures were available in 204 patients. Follow-up data at 12, 24 and 60 months were obtained in 158, 114 and 65 patients, respectively. Table 1 shows the age and gender for this cohort in addition to the type of surgical decompression performed. A similar distribution of type of operation was noted when comparing the 3 month and 60 month outcome cohorts in addition to the number of operated levels for anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) patients. Table 2 is a list of post-operative complications for this group.

Table 1.

Demographics and types of surgery

| Age (years) | Median = 60 | Interquartile range = 47–69 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male = 121 (59 %) | Female = 83 (41 %) | |

| Treatment (number of patients at each number of operated levels) | ACD (no graft or fixation) | Single level | 106 |

| Two levels | 40 | ||

| Three levels | 8 | ||

| Cervical Laminectomy/laminoplasty | 27 | ||

| Anterior decompression and reconstruction | 7 (all >2 operated levels) | ||

| Posterior decompression and fixation | 16 | ||

Table 2.

Post-operative complications

| Mortality | 0 | |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological deficit | Sensory | 0 |

| Motor | 3 (1.5 %) | |

| Dural tear | 1 (0.5 %) | |

| Laryngeal nerve palsy | 1 (0.5 %) | |

| Urinary retention | 3 (1.5 %) | |

| Wound infection | 7 (3.4 %) | |

| Haematoma | 6 (2.9 %) | |

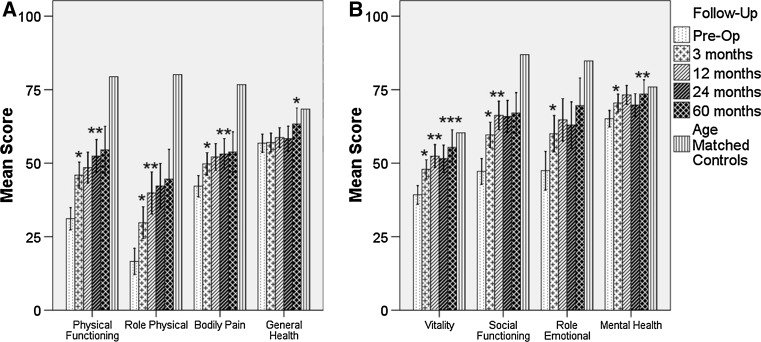

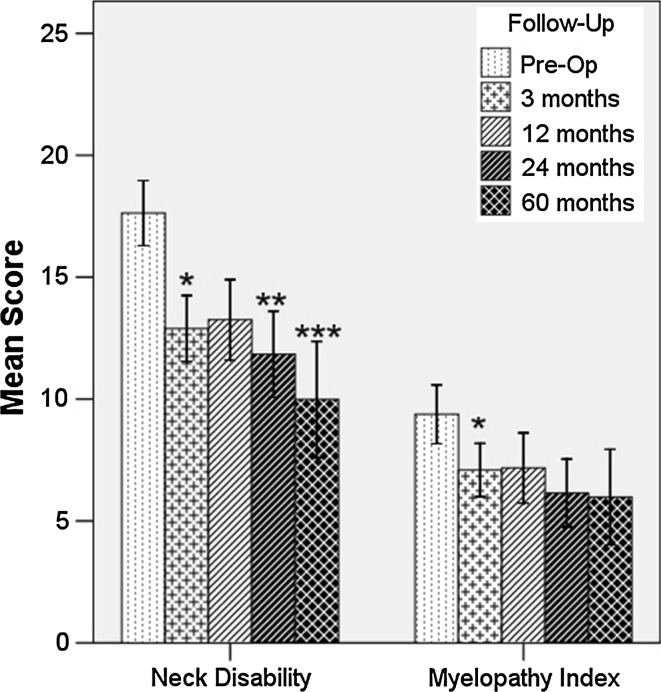

Figure 1 shows the physical and emotional domains of the SF-36, respectively, at all time points with age-matched controls. Pre-operative patients demonstrated lower scores than age-matched controls. Significant improvements were noted 3 months post-operatively. These improvements were maintained at 60 months follow-up with further statistically significant improvements noted in most physical and emotional domains. Figure 2 demonstrates scores for the Neck Disability Index and Myelopathy Disability Index. Significant improvements were noted at 3 months post-operatively and once again these improvements were maintained at 60 months follow-up. Further significant improvements were noted in the Neck Disability Index at 24 and 60 months.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores from the physical (a) and emotional (b) domains of the SF-36 at all time points. Age-matched controls are shown. Asterisk denotes significance at p = 0.05. Double asterisk and triple asterisk show further significance at p = 0.05 from the last time point with significant change. Error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals

Fig. 2.

Mean scores of the Neck Disability Score and Myelopathy Index. Asterisk denotes significance at p = 0.05. Double asterisk and triple asterisk show further significance at p = 0.05 from the last time point with significant change. Error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals

Figure 3a demonstrates the visual analogue scores for neck and arm pain. Improvements were noted following surgery, although this did not reach statistical significance until 12 months post-operatively for neck pain. Further improvements in arm pain were noted at 60 months. Figure 3b demonstrates similar results for visual analogue scores for arm and hand tingling.

Fig. 3.

Mean visual analogue scores for a neck pain and arm pain and b arm paraesthesia, arm tingling and hand tingling. Asterisk denotes significance at p = 0.05. Double asterisk and triple asterisk show further significance at p = 0.05 from the last time point with significant change. Error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals

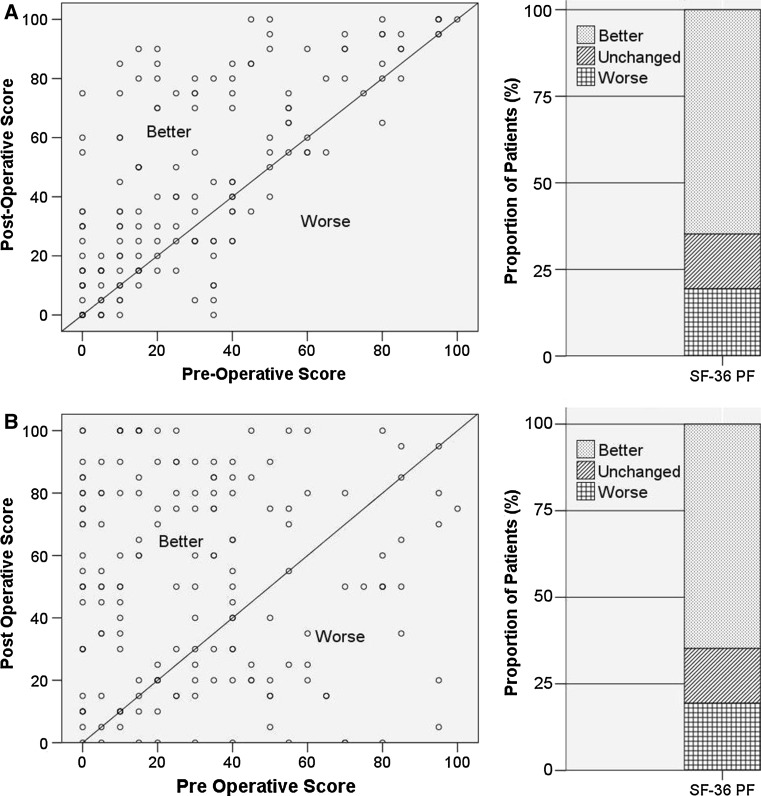

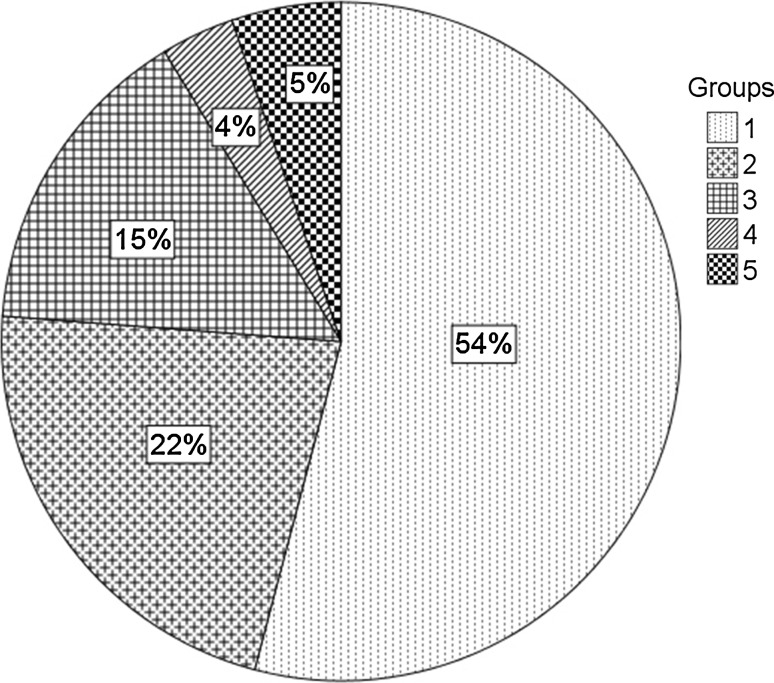

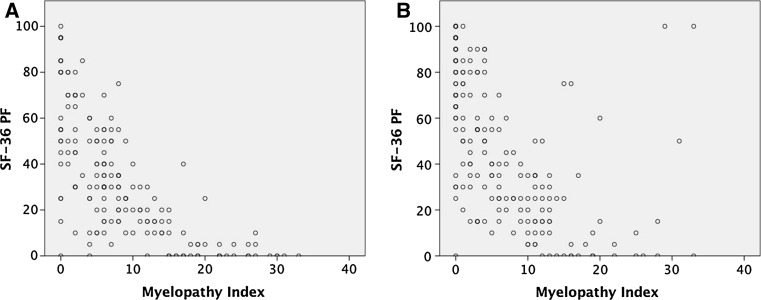

Figure 4a shows the physical function domain of the SF-36 and demonstrates that approximately 70 % are improved at 3 months post-operatively (66 % for only those myelopathic patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy). Figure 4b demonstrates similar physical domain results, but for long-term follow-up of each patient (i.e. as long as is available from this dataset). Figure 5 groups individual patients into groups depending on their initial response following surgery. Most patients improve and either maintain this improvement or continue to improve. Figure 6 demonstrates scatter plots of SF-36 physical form against Myelopathy Disability Index at pre-operative (7a) and 3 months post-operative (7b) time points. There is a statistically significant negative correlation between the two factors.

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients improved at a 3 months and b long-term follow-up as assessed by the physical domain of the SF-36

Fig. 5.

Outcome of individual patients as assessed by the physical form domain of the SF-36. Group 1 and 2 were improved at 3 months. In group 1 this improvement was maintained; in group 2, subsequent deterioration is noted. Groups 3 and 4 are worse at 3 months. Group 3 subsequently improved on long-term follow-up; group 4 continued to deteriorate. Group 5 showed no change at 3 months and long-term follow-up

Fig. 6.

Scatter plots of SF-36 PF and Myelopathy Disability Index at a pre-operative assessment and b 3 months following surgery. A significantly negative correlation was noted at both time points (pre-operative: Spearman’s rho −0.78, p < 0.0001; 3 months: Spearman’s rho −0.69, p < 0.0001)

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that patients with CSM treated by surgical decompression show significant improvements in generic and condition-specific outcome measures in 70 % of the cohort. For SF-36, pre-operative scores were lower than age-matched controls in all domains and significant improvements were seen 3 months following surgery. This improvement in outcome was maintained at 5 years follow-up in approximately two-thirds of those with initial improvement. The physical form domain of the SF-36 correlated strongly with myelopathy disability index pre-operatively and at 3 months.

Disease-specific measures focus on impairments associated with a single disease. Historically, patients with CSM have been assessed using scales to assess the severity of myelopathy. These include the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Scale (JOA) and the Nurick Scale [3]. These scales evaluate functional status specifically affected by CSM such as ambulation, sphincter control and sensation. The Neck Disability Index is a modification of the Oswestry Low Back Pain Index and is produced by a 10-item scaled questionnaire. This has previously been validated in patients with chronic neck pain [5]. The Myelopathy Disability Index has been developed from the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [6]. It has been validated in a study of 100 patients with CSM [7]. Our results have demonstrated the responsiveness of both of these condition-specific measures following surgery. However, they do not evaluate deficits associated with emotional and mental health or extend to measuring quality of life. Outcome measures including the SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, patient perceived outcome, World Health Organisation Quality of Life-Brief and preference-based quality of life instruments have all been investigated in this setting [4, 8–13]. Anxiety and depression have significant bearing on overall outcome. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale has been developed to be a self-assessment of mood to be used in non-psychiatric hospital departments [14]. On initial assessment, approximately 25 % of patients were noted to be anxious or depressed according to this scale (scoring >10). This is comparable to a recent prospective study demonstrating these figures to be 38 % for anxiety and 29 % for depression in a cohort of 89 patients [12]. Our results demonstrate improvements in anxiety and depression following surgery that are maintained on long-term follow-up.

The SF-36 outcome measures were designed to measure the burden of illness experienced by patients with a wide range of medical conditions. Previous studies have validated the use of SF-36 in CSM [4, 9]. It has been noted that the SF-36 gives insight into aspects of health and outcome not taken into consideration by condition-specific myelopathy scales [9]. However, the SF-36 lacks specific information regarding neurological deficits seen in CSM. As such, it has been suggested that both the SF-36 and myelopathy scales should be used to complement each other and provide a more sensitive measure of outcome [9]. Our results have demonstrated that patients with CSM have considerably lower SF-36 scores than age-matched controls in all domains. This is supported by earlier studies that have demonstrated cohort scores significantly lower than age-matched controls in all domains [8, 13]. The scores reacted appropriately following surgery and were as responsive as condition-specific measures in the long-term follow-up. This improvement has been demonstrated in other studies [8, 13]. The improvements in physical domains, even in those without improvement in condition-specific measures such as the Nurick grading system, was postulated to be a placebo effect [8, 13]. Our study contradicts this since both pre-operative and post-operative SF-36 scores of the physical domain correlated well with the condition-specific outcome measures used in our study.

In this study significant improvements following surgery are seen in all the outcome scales in the majority of patients. Most published series investigating outcome following surgery for CSM contain a significant proportion of patients who are worse or unchanged following surgery [1]. This is in agreement with our data with approximately one-third of patients demonstrating no improvement following surgery. When CSM patients are assessed cross-sectionally, it has been demonstrated that previous cervical surgery is associated with lower SF-36 scores than those patients with no previous surgery [8]. However, this does not determine what effect surgery might have had on these patients due to the lack of pre-operative baseline data. It must be emphasised that our data do not represent a comparison of outcome in surgically and conservatively treated patients, but demonstrate durable improvements following surgery in a proportion of patients.

Conclusion

We have used generic and condition-specific outcome measures of health in patients with cervical myelopathy undergoing surgical treatment. Seventy per cent of patients can anticipate worthwhile improvements in quality of life following surgery and in many these health gains are maintained in the longer term. These outcome measures are straightforward to administer and should provide the basis for measurement of outcome in all patients undergoing surgery for cervical myelopathy.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.King JT, Jr, Moossy JJ, Tsevat J, Roberts MS. Multimodal assessment after surgery for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2(5):526–534. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geigle R, Jones SB. Outcomes measurement: a report from the front. Inquiry. 1990;27(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jankowitz BT, Gerszten PC. Decompression for cervical myelopathy. Spine J. 2006;6(6 Suppl):317S–322S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latimer M, Haden N, Seeley HM, Laing RJ. Measurement of outcome in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy treated surgically. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16(6):545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebersold MJ, Pare MC, Quast LM. Surgical treatment for cervical spondylitic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 1995;82(5):745–751. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.5.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey AT, Bland JM, Crockard HA. Development of a functional scoring system for rheumatoid arthritis patients with cervical myelopathy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(12):901–906. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.12.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh A, Crockard HA. Comparison of seven different scales used to quantify severity of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and post-operative improvement. J Outcome Meas. 2001;5(1):798–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King JT, Jr, McGinnis KA, Roberts MS. Quality of life assessment with the medical outcomes study Short Form-36 among patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurg. 2003;52(1):113–120. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King JT, Jr, Roberts MS. Validity and reliability of the Short Form-36 in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(2 Suppl):180–185. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.2.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King JT, Jr, Tsevat J, Moossy JJ, Roberts MS. Preference-based quality of life measurement in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29(11):1271–1280. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200406010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajshekhar V, Muliyil J. Patient perceived outcome after central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Surg Neurol. 2007;68(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoffman MR, Roberts MS, King JT., Jr Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, depression, and anxiety: a cohort analysis of 89 patients. Neurosurg. 2005;57(2):307–313. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000166664.19662.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakar S, Christopher S, Rajshekhar V. Quality of life assessment after central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: comparative evaluation of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey and the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(4):402–412. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.SPINE08749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]