Abstract

We evaluated the outcomes and associated prognostic factors in 233 patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for primary myelofibrosis (MF) using reduced intensity conditioning (RIC). Median age at HCT was 55 years. Donors were: matched sibling donor (MSD), 34%; HLA-well-matched unrelated donors (URD), 45%; and partially/mismatched URD, 21%. Risk stratification according to Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS): low, 12%; intermediate-1, 49%; intermediate-2, 37%; and high, 1%. The probability of survival at 5-years was 47% (95% CI 40–53). In a multivariate analysis, donor type was the only independent factor associated with survival. Adjusted probabilities of survival at 5-years for MSD, well matched URD and partially matched/mismatched URD were 56% (95% CI 44–67), 48% (95% CI 37–58), and 34% (95% CI 21–47), respectively (p=0.002). Relative risks (RR) for NRM for well-matched URD and partially matched/mismatched URD were 3.92 (p=0.006) and 9.37 (p<0.0001), respectively. A trend towards increased NRM (RR 1.7, p=0.07) and inferior survival (RR 1.37, p=0.10) was observed in DIPSS-intermediate-2/high-risk patients compared to DIPSS-low/intermediate-1 risk patients.

RIC HCT is a potentially curative option for patients with MF, and donor type is the most important factor influencing survival in these patients.

Keywords: Myelofibrosis, allogeneic transplantation, reduced intensity, prognosis

Introduction

Primary Myelofibrosis (MF) is a clonal stem cell disorder characterized by cytopenias, splenomegaly, marrow fibrosis, and systemic symptoms due to elevated inflammatory cytokines. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is the only known curative treatment option for MF. Full-intensity conditioning (FIC) in older patients with MF is associated with high rate of non-relapse mortality (NRM) restricting the use of this option to younger and fitter patients.1 Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) is increasingly used in patients with MF as shown by the reporting trends from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR).1

The outcome of HCT is usually determined by a complex interaction between various patient-, disease-, and transplant-related variables. Although potentially curative, HCT in MF is associated with significant risk of morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors associated with outcomes to determine which patients are likely to benefit from this approach. Prior studies evaluating the prognostic factors in MF patients undergoing HCT reported conflicting results.2–6 The reasons for these discrepant results are probably related to heterogeneity of the disease and patient populations, and small sample sizes lacking statistical power; and thus inability to analyze these factors in multivariate analysis.

Our understanding of natural history of primary MF has significantly improved with the evolution of new prognostic systems. The prognostic systems are important tools for assessing the risk of mortality associated with the disease; and therefore can be useful in determining the candidacy for HCT. Lille-score is the conventional prognostic scoring system, and divides patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories.7 International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) was recently developed by International Working Group of Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment.8 Five independent risk factors at diagnosis, age >65 years, hemoglobin <100g/L, WBC count >25 × 109/L, circulating blasts >1%, and presence of constitutional symptoms, were predictive of shorter survival in patients with primary MF. The presence of 0,1,2 and ≥3 factors are categorized as low-,intermediate-1-, intermediate 2-, and high-risk disease with a median survival of 135, 95, 48 and 27 months, respectively. The risk factors for IPSS were also validated in a time dependent fashion known as dynamic IPSS (DIPSS).9 DIPSS is used to assess the risk of mortality anytime during the disease course. Further refinement of DIPSS was proposed by incorporating cytogenetics, transfusion dependency and thrombocytopenia creating the DIPSS plus scoring system.10 DIPSS has largely replaced Lille score in assessing the risk of mortality in primary MF.

The utility of new scoring systems in predicting the outcomes of patients undergoing RIC transplantation is not well understood. Two recent studies reported that post-HCT success was dependent on pre-HCT DIPSS scores.6,11 A large proportion of patients received FIC in these studies. Another study from the European Blood and Marrow Transplant (EBMT) group reported that DIPSS although predictive, did not sufficiently differentiate between intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 risk populations in patients undergoing RIC HCT for MF.2

Additionally, a variety of RIC regimens with varying intensity have been used in MF.4,12–16 Superiority of one regimen over other is not established. The impact of other transplant-related factors such as conditioning regimen, donor type, and GVHD prophylaxis is not well studied in the RIC setting. Therefore, the Chronic Leukemia Working Committee of the CIBMTR sought to determine the outcomes of patients with primary MF undergoing HCT using RIC, and analyzed the impact of patient, disease and transplant related factors on outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

The CIBMTR is a combined research program of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program. CIBMTR comprises a voluntary network of over 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on consecutive allogeneic and autologous HCT to a centralized statistical center. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR's capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Additional details regarding the data source are described elsewhere.17

Patient populations

We identified adult patients >18 years, receiving a first allogeneic transplant for primary MF from a related or unrelated donor between 1997 and 2010 using a RIC regimen. The intensity of conditioning regimen was defined as per CIBMTR consensus criteria.16 Patients whose disease had progressed to acute myeloid leukemia prior to HCT were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria included: syngeneic transplants, cord blood transplants, haplo-identical transplants, and in-vitro T-cell depleted grafts. Unrelated donor (URD) transplant recipients were classified based on available HLA typing as previously described.18

Prognostic scoring systems

Risk stratification according to DIPSS score was calculated at the time of HCT.9 DIPSS-risk categorization could not be determined in 3 patients (<1%) due to missing data. Because of missing cytogenetics in 36% of the patients, we were not able to evaluate DIPSS plus in this study.

Cytogenetics

Results of cytogenetics testing were reviewed as provided by the transplantation center, and classified as normal karyotype and abnormal karyotype. Abnormal karyotype was further sub-divided as unfavorable and other abnormalities. Unfavorable cytogenetics was defined as previously described and included: complex abnormalities (≥3) or single or two abnormalities including +8, −7/7q-, i(17q), −5/5q-, 12p-, inv(3) or 11q23 rearrangements.10

Endpoints

The primary end point of the study was overall survival (OS). Other end points of interests were hematopoietic recovery, acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), relapse/progression, non-relapse mortality (NRM), and progression-free survival (PFS). OS was defined as time from HCT to death from any cause, and patients were censored at the last follow-up. Relapse/progression was reported by the transplant centers, and NRM was considered a competing event. NRM was defined as death within the first 28 days of transplant from any cause or death without evidence of disease progression/recurrence; relapse/progression was considered a competing event. PFS was defined as time to treatment failure (death or relapse/progression). For relapse/progression, NRM, and PFS, patients alive in continuous complete remission were censored at last follow-up. Hematopoietic recovery was defined as time to absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 0.5 × 109/L sustained for three consecutive days and time to achieve a platelet count of >20 × 109/L independent of platelet transfusions for 3 consecutive days. Acute and chronic GVHD were diagnosed and graded according to consensus criteria.19,20

Statistical methods

Univariate probabilities of OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator; the log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons. Probabilities of hematopoietic recovery, aGVHD, cGVHD, NRM, and relapse/progression were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Potential risk factors for OS, NRM, relapse and PFS were evaluated in multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression. The proportional hazards assumption was tested. Step-wise selection procedure was used to select significant covariates. Factors significantly associated with the outcome variable at a 5% level were kept in the final model. All p-values were two-sided. First order interactions between the main effect and significant covariates were tested. An analysis evaluating the impact of aGVHD/cGVHD as time dependent covariates on survival, NRM, relapse/progression, PFS was conducted. Adjusted 5-year survival probabilities were estimated through the direct adjusted survival curves estimation method.21 SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used in all analyses.

Variables considered in the multivariate analysis

The following patient, disease and transplant related factors were included in the multivariate model: patient age in years (≤40 vs. 41–60 vs. >60), gender, Karnofsky performance scores (<90 vs. ≥90), DIPSS (low/Intermediate-I vs. Intermediate-II/high), platelet count (<100 × 109/L vs. ≥100 × 109/L), spleen status (normal spleen vs. splenomegaly vs. splenectomy vs. missing), time of diagnosis to HCT, conditioning regimen (fludarabine and total body irradiation [FluTBI]-based vs. fludarabine and melphalan [FluMel]-based vs. fludarabine and busulfan [FluBu]-based vs. others), donor type [matched sibling donor (MSD) vs. well matched URD vs. partially matched/mismatched URD], GVHD prophylaxis (tacrolimus -based vs. cyclosporine-based vs. all others), and the year of HCT (≤2003 vs. ≥2003).

Results

Patient, disease and transplantation characteristics

A total of 233 patients from 83 transplantation centers met the study eligibility criteria: 79 patients received HCT from MSD, and 154 from URD. Among the URD transplant recipients, 104 (67%) were HLA-well-matched with their donors and 50 (33%) were partially/mismatched. Median age at HCT was 55 years (range, 19–79), and 64 patients (27%) were >60 years. Median follow-up of survivors was 50 months (range, 3–134 months). Completeness index of follow-up for the study population at 3 and 5 years was 94% and 90%, respectively.22

Baseline patient, disease, and transplantation characteristics of the study patients are listed in Table 1. Conditioning regimens were: FluTBI-based, 51(22%); FluMel-based, 65(28%); FluBu-based, 89 (38%); and others 28 (12%). Median doses and interquartile range (IQR) of various cytotoxic agents in the various regimen are as: FluTBI, Flu 90 mg/m2 (IQR 88–118) and single fraction TBI 200cGY (IQR 200-200) or fractionated TBI 800cGy (IQR 800–800); Flu Mel, Flu 129 mg/m2 (IQR 122–147) and Mel 139 mg/m2 (IQR 132–140); and Flu Bu, Flu 157 mg/m2 (IQR 124–178) and oral Bu 8 mg/Kg (IQR 7–8) or IV Bu 6 mg/Kg (IQR 5–6).

Table 1.

Patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related characteristics

| Characteristic of patients | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 233 |

| Number of centers | 83 |

| Age, median(range), years | 55 (19 – 79) |

| 18–40 | 12 (5) |

| 41–60 | 157 (67) |

| >60 | 64 (27) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 151 (65) |

| Female | 82 (35) |

| Karnofsky score | |

| <90% | 84 (36) |

| 90–100% | 135 (58) |

| Missing | 14 (6) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant (range), months | 15 (2 – 305) |

| Constitutional symptoms prior to HCT | |

| No | 182 (78) |

| Yes | 42 (18) |

| Missing | 9 (4) |

| Circulating blasts in blood at HCT | |

| Absent | 132 (57) |

| ≥1% | 101 (43) |

| Spleen status at transplant | |

| Spleen not palpable | 52 (22) |

| Splenomegaly | 113 (48) |

| Splenectomy | 59 (25) |

| Missing | 9 (4) |

| Cytogenetics prior to HCT | |

| Not evaluable/missing | 84(36) |

| Normal Karyotype | 89 (38) |

| Abnormal | 66 (28) |

| Unfavorable | 30(13) |

| Other abnormalities | 30 (13) |

| Hemoglobin at HCT | |

| <100g/L | 148(64) |

| ≥100g/L | 85 (36) |

| Platelet count at transplant (range), × 109/L | 121 (5 – 1835) |

| Platelet count prior to transplant | |

| <100 × 109/L | 94 (40) |

| ≥100 × 109/L | 116 (50) |

| Missing | 23 (10) |

| WBC count at transplant (range), × 109/L | 6 (<1 – 431) |

| DIPSS at transplant | |

| Low risk | 27 (12) |

| Int-1 | 114 (49) |

| Int-2 | 86 (37) |

| High-risk | 3 (1) |

| Missing | 3 (1) |

| Graft type | |

| Bone marrow | 28 (12) |

| Peripheral blood | 205 (88) |

| Donor type | |

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 (34) |

| Well-matched URD | 104 (45) |

| Partially matched URD | 40 (17) |

| Mismatched URD | 10 (4) |

| D-R CMV status | |

| +/+ | 72 (31) |

| +/− | 26 (11) |

| −/+ | 55 (24) |

| −/− | 60 (26) |

| Missing | 20 (9) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| FluTBI-based | 51 (22) |

| FluMel-based | 65 (28) |

| FluBu-based | 89 (38) |

| Others | 28 (12) |

| ATG or alemtuzumab use | |

| ATG | 110 (47) |

| Alemtuzumab | 13 (6) |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |

| Tarcrolimus-based | 105 (45) |

| Cyclosporine-based | 124 (53) |

| Other GVHD prophylaxis | 4 (2) |

| Year of transplant | |

| 1997–2001 | 26 (11) |

| 2002–2006 | 116 (50) |

| 2007–2010 | 91 (39) |

| Median follow-up of survivors, range, months | 50 (3 – 134) |

Risk stratification at HCT according to DIPSS was: low 27 (12%), intermediate-1 114 (49%), intermediate-2 86 (37%), and high, 3 (1%), and missing in 3 patients (1%). Due to small numbers of DIPSS-low or high-risk patients, DIPSS groups were collapsed into low/intermediate-1, 141 (61%); and intermediate-2/high, 89 (38%).

Transplantation outcomes

Primary end point: overall survival

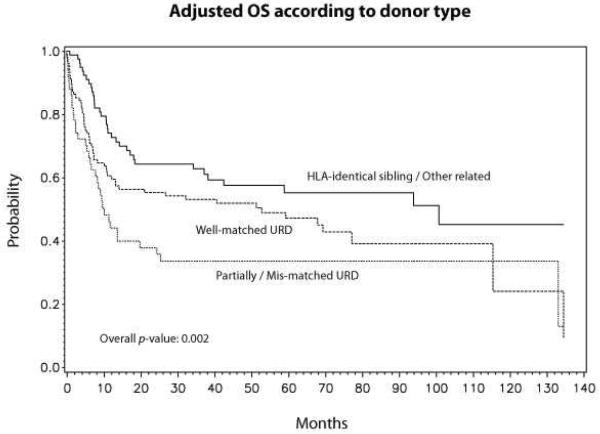

The probability of OS at 5-years was 47% (95% CI 40–53, Table 2, Fig 1). In a multivariate analysis, donor type was the only independent factor associated with survival with a RR of 1.57 (95% CI 1.01–2.46) for well-matched URD and 2.48 (95% CI 1.51–4.04) for partially matched/mismatched URD (Table 3). Adjusted probabilities of survival at 5-years for MSD, well matched URD and partially matched/mismatched URD were 56% (95% CI 44–67), 48% (95% CI 37–58), and 34% (95% CI 21–47), respectively (p=0.002) (Fig 2).

Table 2.

Post HCT outcomes: univariate analysis (Study population n=233)

| Outcomes | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil engraftment | 232 | |

| 28-day | 84 (78–88)% | |

| 100-day | 97 (92–99)% | |

| Platelet recovery | 215 | |

| 28-day | 47 (40–53)% | |

| 100-day | 77 (70–82)% | |

| Grade 2–4 acute GVHD | 232 | |

| 100-day | 37 (30–43)% | |

| Grade 3–4 acute GVHD | 232 | |

| 100-day | 19 (15–25)% | |

| Chronic GVHD | 224 | |

| 1-year | 42 (35–48)% | |

| 3-year | 50 (43–57)% | |

| 5-year | 51 (44–58)% | |

| Relapse/progression | 218 | |

| 1-year | 43 (36–49)% | |

| 3-year | 47 (40–53)% | |

| 5-year | 48 (42–55)% | |

| Non-relapse mortality | 218 | |

| 1-year | 18 (13–23)% | |

| 3-year | 22 (16–27)% | |

| 5-year | 24 (18–31)% | |

| Progression-free survival | 218 | |

| 1-year | 39 (33–46)% | |

| 3-year | 32 (26–38)% | |

| 5-year | 27 (21–34)% | |

| Overall survival | 233 | |

| 1-year | 62 (55–68)% | |

| 3-year | 52 (45–58)% | |

| 5-year | 47 (40–53)% |

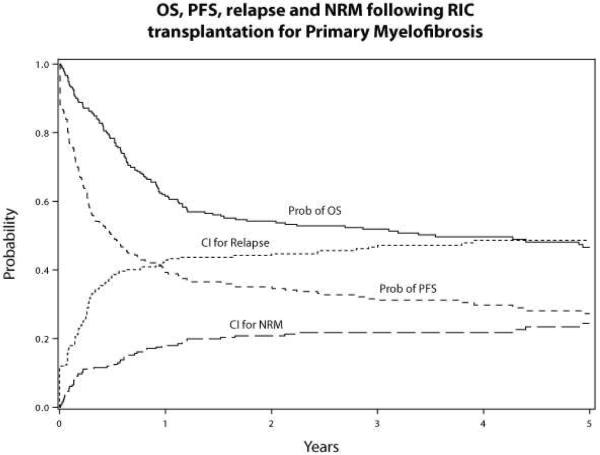

Figure 1.

OS, PFS, relapse and NRM following RIC transplantation for Primary MF

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for aGVHD, cGVHD, Relapse/Progression, NRM, PFS and Overall Survival.

| N | RR | p-value | 95% CI | Overall p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Grade 2–4 acute GVHD

| |||||

| Donor type | 0.02 | ||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 | 1 | |||

| Well-matched URD | 104 | 1.98 | 0.006 | 1.22–3.22 | |

| Partially matched/mismatched URD | 50 | 1.52 | 0.18 | 0.83–2.80 | |

| Contrast | |||||

| Well-matched URD vs. Partially matched/mismatched URD | 1.30 | 0.33 | 0.76–2.23 | ||

|

Chronic GVHD

| |||||

| Donor type | 0.33 | ||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 | 1 | |||

| Well-matched URD | 104 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.51–1.26 | |

| Partially matched/mismatched URD | 50 | 1.21 | 0.49 | 0.67–2.10 | |

|

Relapse/Progression

| |||||

| DIPSS | |||||

| Low/Intermediate-1 | 141 | 1 | 0.04 | ||

| Intermediate-2/high | 89 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.42–0.99 | |

|

NRM

| |||||

| DIPSS | |||||

| Low/Intermediate-1 | 141 | 1 | 0.07 | ||

| Intermediate-2/high | 89 | 1.70 | 0.07 | 0.96–3.01 | |

| Donor type | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 | 1 | < 0.001 | ||

| Well-matched URD | 104 | 3.92 | 0.006 | 1.50–10.33 | |

| Partially matched/mismatched URD | 50 | 9.37 | < 0.001 | 3.49–25.17 | |

| Contrast | |||||

| Well-matched URD vs. Partially matched/mismatched URD | 0.42 | 0.005 | 0.23–0.77 | ||

|

PFS

| |||||

| DIPSS | |||||

| Low/Intermediate-1 | 141 | 1 | 0.55 | ||

| Intermediate-2/high | 89 | 0.90 | 0.55 | 0.65–1.26 | |

| Donor type | 0.03 | ||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 | 1 | |||

| Well-matched URD | 104 | 1.17 | 0.42 | 0.80–1.69 | |

| Partially matched/mismatched URD | 50 | 1.75 | 0.01 | 1.14–2.68 | |

| Contrast | |||||

| Well-matched URD vs. Partially matched/mismatched URD | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.45–0.99 | ||

|

Overall Survival

| |||||

| DIPSS | |||||

| Low/Intermediate-1 | 141 | 1 | 0.10 | ||

| Intermediate-2/high | 89 | 1.37 | 0.10 | 0.95–1.98 | |

| Donor type | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 79 | 1 | 0.002 | ||

| Well-matched URD | 104 | 1.57 | 0.05 | 1.01–2.46 | |

| Partially matched/mismatched URD | 50 | 2.48 | 0.0003 | 1.51–4.04 | |

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| FluTBI-based | 51 | 1 | 0.14 | ||

| FluMel-based | 65 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 0.41–1.23 | |

| FluBu-based | 89 | 1.13 | 0.63 | 0.70–1.82 | |

| Others | 28 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 0.76–2.62 | |

| Contrast | |||||

| FluMel-based vs. FluBu-based | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.39–1.02 | ||

| FluMel-based vs. Others | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.27–0.95 | ||

| FluBu-based vs. Others | 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.46–1.41 | ||

| Well-matched URD vs. Partially matched/mismatched URD | 0.64 | 0.04 | 0.41–0.98 | ||

Figure 2.

Adjusted survival according to donor type (MSD vs. well matched URD vs. partially matched/mismatched URD

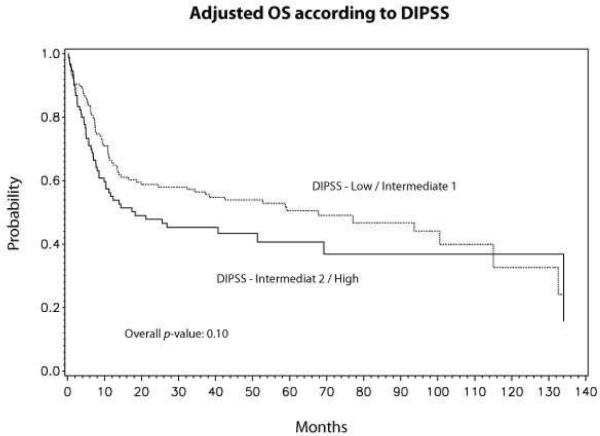

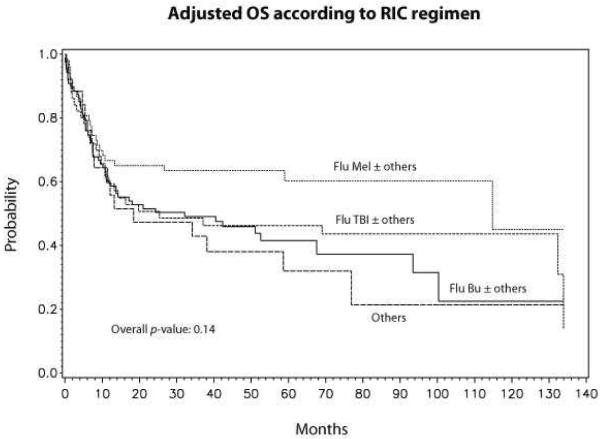

Although not statistically significant, there was a trend in lower overall mortality between DIPSS low/intermediate-1 risk vs. DIPSS intermediate-2/high-risk disease (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.95–1.98, p=0.10) (Table 3). Adjusted probabilities of survival at 5 years for low/intermediate-1 and intermediate-2/high-risk disease were 51% (95% CI 42–59) and 41% (95% CI 30–52), respectively (Fig 3). The conditioning regimen was not significantly associated with OS (Table 3). However, when individual conditioning regimens were compared against each other FluMel-based regimen had a trend towards lower mortality compared to FluBu based regimen (RR 0.63, p=0.06). Adjusted probabilities of survival at 5-years according to conditioning regimen were: FluMel-based, 59% (95% CI 32–59); FluTBI-based, 46% (95% CI 32–59); FluBu-based, 41% (95% CI 28–53); and others, 28% (95% CI 8–47) (Fig 4).

Figure 3.

Adjusted survival according to DIPSS risk stratification (Low/Intermediate-1 vs. Intermediate-2/high)

Figure 4.

Adjusted survival according to type of RIC regimen

Secondary end points

Hematopoietic recovery

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at 28 days and 100 days was 84% (95% CI 78–88) and 97% (95% CI 92–99%), respectively (Table 2). The corresponding values for platelet recovery at day 28 and day 100 were 47% (95% CI 40–53), and 77% (95% CI 70–82), respectively. There was no significant difference in neutrophil (log-rank p=0.52) or platelet recovery (log-rank p=0.87) according to donor type.

Acute and chronic GVHD

The cumulative incidence of grade II–IV and grade III–IV aGVHD at 100 days was 37% (95% CI 30–43) and 19% (95% CI 15–25), respectively (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 5 years was 51% (95% CI 44–58) (Table 2). In a multivariate analysis, URD transplants had significantly higher (p=0.02) risk of acute GVHD and RR for well-matched URD and partially matched/mismatched URD were 1.98 (95% CI 1.21–3.22, p=0.006) and 1.52 (95% CI 0.82–2.80, p=0.18) compared to MSD transplants (Table 3). No differences in chronic GVHD were observed in different donor types (p=0.33) (Table 3).

The impact of aGVHD/cGVHD on transplant outcomes was evaluated (Supp Table). Patients who developed “acute GVHD, but no cGVHD” had significantly higher NRM, and lower relapse/progression compared to “no acute or chronic GVHD” group. No differences on PFS or survival were observed.

NRM, relapse/progression and PFS

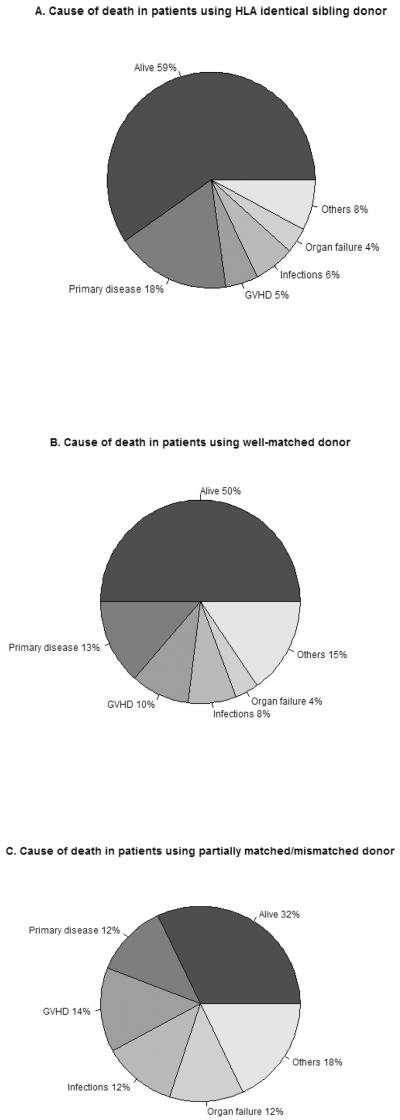

At 5-years, the cumulative incidence of NRM and relapse/progression at 5-years was 24% (95% CI 18–31) and 48% (95% CI 42–55), respectively and probability of PFS was 27% (95% CI 21–34) (Table 2, Figure 1). In a multivariate analysis, donor type was independently associated with higher NRM (p<0.0001), and RR of NRM were 3.92 (95% CI 1.48–10.32, p=0.006) and 9.37 (95% CI 3.4–25.16, p<0.0001) (Table 3). The causes of death according to donor type are shown in figure 5. The main causes of NRM were GVHD, infections and organ failure and all these complications were higher in partially matched/mismatched URD (Fig 5). There was a trend towards higher NRM in DIPSS int-2/high risk category (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.96–3.01, p=0.07) (Table 3). No impact of donor type was observed in relapse/progression, however unexpectedly, we found that patients with DIPSS-Intermediate-2/high-risk had lower risk of relapse compared to low/intermediate-1 risk patients (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.42–0.98, p=0.04) (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Cause of death in patients with MF undergoing RIC transplantation using

A. matched sibling donor;

B. well-matched unrelated donor;

C. patially matched/mismatched unrelated donor.

Donor type had significant impact on PFS (p=0.03) and PFS was significantly inferior for partially matched/mismatched URD. RR for PFS for well-matched URD and partially matched URD/mismatched URD were 1.17 (95% CI 0.80–1.69, p=0.42) and 1.75 (1.14–2.68, p=0.01), respectively (Table 3). DIPSS risk category had no impact on PFS (p=0.55)

Impact of cytogenetics

In an exploratory analysis, we evaluated the impact of cytogenetics on survival after adjusting for donor type. Patients with unfavorable cytogenetics had nearly two-fold mortality compared to normal karyotype (RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.16–3.38). There was no significant difference between patients with normal karyotype and those who had abnormalities other than unfavorable (RR 1.4, 95% CI 0.78–2.5).

Discussion

This report represents the largest international multi-center experience of reduced intensity transplantation in patients with primary MF, and reinforces the curative potential of RIC transplantation in patients with MF. Recently published studies, where patients primarily underwent FIC regimens, have shown the impact of higher DIPSS scores on survival of patients with MF.6,11 In our study, a trend towards increased NRM (p=0.07) and inferior survival (p=0.10) was observed in DIPSS-intermediate-2/high-risk patients compared to DIPSS-low/intermediate-1 risk patients. It is noteworthy that there were very few patients with DIPSS-low risk and DIPSS-high risk category in our study, so the main measured effect in our study is between DIPSS-Intermediate 1 and DIPSS-Intermediate 2. Another multi-center study from Germany evaluated prognostic factors in 150 patients undergoing RIC transplantation for MF, and reported that DIPSS discriminated poorly between intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 risk patients. The discrepancy between previously reports, and the current study is the result of a number of factors; a considerable one being dissimilar study populations.2,6,11 The current study was restricted to primary MF patients, whereas approximately 40% of patients reported in previous studies included patients with post ET/post PV-MF. It is noteworthy that various risk stratification systems are derived from patients with primary MF7–10, and have not been validated for secondary MF. About 70–85% of patients in previously reported studies were treated with FIC.6,11 The sample size of the current study is significantly larger compared to contemporary studies; though there were very few patients with DIPSS-high-risk disease. A study from Germany reported that wild type JAK2, age ≥57 years and constitutional symptoms were all associated with inferior survival.2 Age was not found to have an independent prognostic impact in the current study in a patient population undergoing RIC transplantation. The prognostic significance of JAK2 mutation could not be analyzed as a result of missing data regarding JAK2 mutation status on a large proportion of patients.

Perhaps, one of the most important findings of the current study is the independent adverse impact of donor type on NRM and survival. Mortality risk associated with well-matched URD and partially matched/mismatched URD were significantly higher when compared to MSD transplants. A prospective RIC study using FluBu-based conditioning reported similar outcomes with MSD and well-matched URD, whereas results were inferior for a small number of patients with mismatched URD.12 Preliminary results of another prospective study from the Myeloproliferative Diseases- Research Consortium (MPD-RC) using FluMel-based conditioning described significantly inferior outcomes of URD transplants.15 This finding is of important clinical value as the optimal timing of transplant has been a matter of debate with wider availability of JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy.1 One may consider reserving the option of partially matched/mismatched URD transplantation at the failure of JAK inhibitor therapy, whereas HCT may be considered earlier in the disease course in patients with suitable MSD regardless of response to JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy.

The optimal RIC conditioning regimen in patients with MF is not known. In the current study, patients with FluMel-based regimens appeared to have a trend towards better outcomes when compared to FluBu-based regimens or other regimens. Caution is needed in the interpretation of these results, as there is heterogeneity of the doses of the cytotoxic agents in these regimens. These finding needs to be further confirmed in well-designed prospective studies. We did not find an independent adverse impact of either thrombocytopenia23 or splenomegaly24 and no beneficial impact of pre-transplant splenectomy as found in previous reports.6

Our study also highlights the high rate of relapse/progression noted after RIC transplantation. Unexpectedly, we found a lower risk of relapse in DIPSS-intermediate-2/high risk category. This finding has to be interpreted with caution. As described in the method section, relapse/progression was analyzed as reported in the CIBMTR forms by the transplant center. CIBMTR forms do not collect detailed information on the basis of relapse/progression. There is no consistent definition of relapse/progression in MF patients. International working group for MPN research and treatment (IWG-MRT) have tried to define response criteria for use in clinical trials. There are no published reports of use of these criteria in BMT patients, and these are hard to apply in retrospective registry studies.

This study has inherent limitations that could influence the data interpretation. Although the sample size of this study, is significantly larger compared to prior reports, is still relatively small. These transplants were done in a time period before the wide availability of JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy. It is uncertain how the wider availability of JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy will influence the field of transplantation for MF, especially the optimal timing. Given that JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy is neither curative nor decreases the risk of leukemic transformation, HCT will continue to remain an important treatment option for suitable patients. Nevertheless, the findings are relevant in modern clinical practice, and demonstrate the curative potential of RIC transplantation in a multi-center setting. The findings of increased mortality associated with partially/matched or mismatched URD further helps in defining the positioning of HCT in the emerging therapeutic options for MF.

In conclusion, RIC HCT is a potentially curative option for some patients with MF. Donor type is the most important factor predicting survival after RIC HCT for MF. Future prospective trials are needed to determine the preferred RIC regimen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24 CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement U10 HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-12-1-0142 and N00014-13-1-0039 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Celgene Corporation; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Remedy Informatics; Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; Tarix Pharmaceuticals; TerumoBCT; Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; THERAKOS, Inc.; and Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gupta V, Hari P, Hoffman R. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for myelofibrosis in the era of JAK inhibitors. Blood. 2012;120:1367–79. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-399048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alchalby H, Yunus DR, Zabelina T, et al. Risk models predicting survival after reduced-intensity transplantation for myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.09009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballen KK, Shrestha S, Sobocinski KA, et al. Outcome of transplantation for myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patriarca F, Bacigalupo A, Sperotto A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in myelofibrosis: the 20-year experience of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Haematologica. 2008;93:1514–22. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robin M, Tabrizi R, Mohty M, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis: a report of the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire (SFGM-TC) Br J Haematol. 2011;152:331–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott BL, Gooley TA, Sorror ML, et al. The Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for myelofibrosis predicts outcomes after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:2657–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupriez B, Morel P, Demory JL, et al. Prognostic factors in agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: a report on 195 cases with a new scoring system. Blood. 1996;88:1013–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood. 2009;113:2895–901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Passamonti F, Cervantes F, Vannucchi AM, et al. A dynamic prognostic model to predict survival in primary myelofibrosis: a study by the IWG-MRT (International Working Group for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment) Blood. 2010;115:1703–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, et al. DIPSS plus: a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:392–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditschkowski M, Elmaagacli AH, Trenschel R, et al. Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System scores, pre-transplant therapy and chronic graft-versus-host disease determine outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2012;97:1574–81. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.061168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroger N, Holler E, Kobbe G, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation after reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with myelofibrosis: a prospective, multicenter study of the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:5264–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta V, Kroger N, Aschan J, et al. A retrospective comparison of conventional intensity conditioning and reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in myelofibrosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:317–20. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rondelli D, Barosi G, Bacigalupo A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in intermediate- or high-risk patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2005;105:4115–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rondelli D, Goldberg JD, Marchioli R, et al. Results of Phase II Clinical Trial MPD-RC 101: Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Conditioned with Fludarabine/Melphalan in Patients with Myelofibrosis. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011;118:1750. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz M. The role of registries in facilitating clinical research in BMT: examples from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisdorf D, Spellman S, Haagenson M, et al. Classification of HLA-matching for retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplantation: revised definitions to predict survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:748–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18:295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:204–17. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Loberiza FR, Klein JP, et al. A SAS macro for estimation of direct adjusted survival curves based on a stratified Cox regression model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;88:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerbauy DM, Gooley TA, Sale GE, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation as curative therapy for idiopathic myelofibrosis, advanced polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:355–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacigalupo A, Soraru M, Dominietto A, et al. Allogeneic hemopoietic SCT for patients with primary myelofibrosis: a predictive transplant score based on transfusion requirement, spleen size and donor type. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:458–63. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.