Abstract

CD36 is a scavenger receptor with multiple ligands and cellular functions, including facilitating cellular uptake of free fatty acids (FFAs). Chronic alcohol consumption increases hepatic CD36 expression, leading to the hypothesis that this promotes uptake of circulating FFAs, which then serve as a substrate for triglyceride (TG) synthesis and the development of alcoholic steatosis. We investigated this hypothesis in alcohol-fed wild-type and Cd36-deficient (Cd36−/−) mice using low-fat/high-carbohydrate Lieber-DeCarli liquid diets, positing that Cd36−/− mice would be resistant to alcoholic steatosis. Our data show that the livers of Cd36−/− mice are resistant to the lipogenic effect of consuming high-carbohydrate liquid diets. These mice also do not further develop alcoholic steatosis when chronically fed alcohol. Surprisingly, we did not detect an effect of alcohol or CD36 deficiency on hepatic FFA uptake; however, the lower baseline levels of hepatic TG in Cd36−/− mice fed a liquid diet were associated with decreased expression of genes in the de novo lipogenesis pathway and a lower rate of hepatic de novo lipogenesis. In conclusion, Cd36−/− mice are resistant to hepatic steatosis when fed a high-carbohydrate liquid diet, and they are also resistant to alcoholic steatosis. These studies highlight an important role for CD36 in hepatic lipid homeostasis that is not associated with hepatic fatty acid uptake.

Keywords: alcoholic steatosis, de novo lipogenesis, fatty acid uptake

Alcoholism is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide (1). Alcoholic steatosis is the first presentation of alcoholic liver disease (ALD), which in the face of continued alcohol consumption can progress to more severe disease states, including alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver failure (2). As a first stage in the ALD spectrum, alcoholic steatosis has been extensively studied in humans and animal models to better understand the mechanisms leading to fat accumulation in the alcohol-exposed liver. This research has indicated that alcohol has many effects on hepatic lipid metabolism, including dysregulation of pathways associated with fatty acid (FA) synthesis, uptake, and oxidation, and triglyceride (TG) synthesis and export; however, the mechanisms underpinning these changes and their relative importance are only beginning to be understood (3).

CD36 (also known as fatty acid translocase) is a class B scavenger receptor that is expressed on the cell surface and can recognize multiple ligands, including long-chain fatty acids, oxidized lipids, and lipoproteins (4). CD36 has multiple cell type-specific physiological functions; for example, its expression in microvascular endothelial cells is associated with angiogenesis, and in the apical cells of taste buds, it is associated with the detection of dietary fatty acids (4, 5). CD36 is also a mediator of free fatty acid (FFA) uptake into tissues, particularly adipose, heart, and skeletal muscle (6, 7). It is thought that CD36 does not normally play a significant role in hepatic FFA uptake; however, under nonphysiological conditions, CD36 is induced in the liver and may contribute to hepatic steatosis (6). For example, pharmacologic activation of liver X receptors increases CD36 expression and TG accumulation in the liver (8), adenoviral-mediated overexpression of hepatic CD36 increases FFA uptake and TG accumulation (9), and liver tissues obtained from patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease also have significantly elevated CD36 expression (10).

Our group and others have observed increased hepatic CD36 expression in alcohol-fed mice at the gene and protein levels (11–13). Given the role of CD36 in facilitating FFA uptake into tissues and the observation that it is upregulated in the alcohol-exposed liver, we hypothesized that CD36 is an important mediator of alcoholic steatosis, acting through its ability to drive hepatic FFA uptake. We tested this hypothesis using wild-type (WT) and Cd36-deficient (Cd36−/−) mice consuming an alcohol-containing low-fat/high-carbohydrate liquid diet. Our data indicate that Cd36−/− mice are resistant to the lipogenic effects of consuming a high-carbohydrate liquid diet and that CD36 deficiency also protects against the development of alcoholic steatosis in these mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal husbandry

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University. Age-matched, male mice, ∼three months of age were used for all studies and were housed in a barrier facility with a 12 h light:dark cycle. Wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) mice and Cd36−/− mice on a congenic C57BL/6 background (14) were used in all experiments.

Alcohol feeding protocol

WT and Cd36−/− mice were randomized onto control or alcohol-containing liquid diets. In all alcohol feeding studies, four groups were compared: WT control, WT alcohol, Cd36−/− control, and Cd36−/− alcohol. The low-fat/high-carbohydrate formulation of the Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet provides 12.5% of calories as fat and 15% as protein. Carbohydrate constitutes 72.5% of calories in control mice and 44.2% in alcohol-fed mice, with the balance of calories (28.3%) coming from ethanol (5.1% alcohol v/v; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ). The carbohydrate composition of the control diet was 30.1 g/l monosaccharides, 25.8 g/l disaccharides, and 111 g/l polysaccharides, and the carbohydrate composition of the alcohol diet was 14.5 g/l monosaccharides, 14.3 g/l disaccharides, and 61.8 g/l polysaccharides. The Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet is a well-established, nutritionally complete alcohol-feeding protocol that allows control mice to be pair-fed isocaloric amounts of the alcohol-free control diet (15). In our studies, control mice from each genotype were pair-fed according to the volume of diet consumed by their alcohol-fed counterparts. During our initial feeding studies, mice were fed a final concentration of 6.4% (v/v) alcohol. The unexpected death of alcohol-fed WT mice (see Supplementary Material) led us to modify our feeding protocol such that mice were fed the control liquid diet for two days, followed by four days consuming 2.1% alcohol, four days with 4.2% alcohol, and six weeks with 5.1% alcohol.

Tissue collection and histology

Tissues were collected in the morning without fasting. First, blood was obtained by retro-orbital bleeding and centrifuged to separate the plasma, which was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Liver tissue was collected, weighed, and snap-frozen. All tissues were stored at −80°C prior to analysis. Two pieces of liver tissue were fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin: one for paraffin embedding and subsequent H and E and Masson's trichrome staining, and one was transferred to a 30% sucrose solution and processed for cryosectioning and Oil Red O staining. All histology was performed by the Pathology Core Facility at the Columbia University Medical Center, and images were captured using an FSX100 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Biochemical analyses

The following kits were used according to the manufacturer's instructions: blood alcohol content (BAC), NAD-alcohol dehydrogenase reagent kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO); plasma TG, liquid stable TG reagent kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Middleton, VA); plasma FFAs, HR series FFA kit (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA); plasma total cholesterol (TC), cholesterol-SL assay (Genzyme diagnostics, Charlottetown, PE, Canada). Blood glucose levels were determined from a tail prick using a glucometer. TG, FFA, and TC levels in the liver were measured using the same kits as above; these measurements were made from a solution (2% triton X-100) of total lipids extracted from liver homogenates using a Folch extraction (16).

Fatty acid uptake studies

FFA uptake was assessed as previously described (17): [14C] 23oleic acid ([14C]OA; 54.6 mCi/mmol, NEC317, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) was dried under a stream of nitrogen and resuspended in 6% FFA-free BSA for at least 2 h (1 μCi/100 μl). Each mouse was injected with 100 μl of [14C]OA:BSA solution via the femoral vein. Mice were bled before injection and at 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 min after injection. They were then perfused with 10 ml of PBS, and tissues were excised for assessment of 14C-dpm by liquid scintillation counting. Plasma clearance curves for the tracer were constructed from these data. Tissue FFA uptake values, expressed as total tissue 14C-dpm, were corrected to total plasma FFA concentrations at baseline.

Measurement of hepatic de novo lipogenesis in vivo

To determine the rate of hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL), each mouse was given an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mCi of [3H]water (ART 0194, 50 mCi/ml, American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc., St Louis, MO). One hour after injection, blood and liver were collected for analysis. 3H-labeled FAs were isolated by saponification of liver samples in KOH. After extraction of nonsaponifiable lipids and acidification with H2SO4, 3H-labeled FAs were extracted and separated by thin layer chromatography and visualized by iodine vapor. The FA fraction was scraped off the plate into a vial containing scintillation fluid and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The specific activity of plasma water (cpm/nmol) was used to calculate the rate of FA synthesis as micromoles of [3H]water incorporated into FA per hour per gram liver tissue (μmol/h/g), as described (18).

Quantitative PCR and Western blotting

Liver RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were performed as previously described (12). The relative mRNA levels of the following genes were determined: Acc1, Acox1, Cd36, Chrebp, Cpt1a, Dgat1, Dgat2, Fabp1, Fatp1, Fatp2, Fatp5, Fasn, G6pc, Lpl, Pdk4, Pepck, Ppara, Pparg, Scd1, and Srebp1c. The primer sequences and full gene names are provided in supplementary Table I. Two reference genes were used for qPCR analysis: 18S and CypA. The changes in target gene expression relative to these reference genes were in good agreement, and only data normalized to CypA expression are presented. Gene expression levels were measured in the livers of mice from two independently conducted alcohol feeding studies. The experimental results from these studies were in good agreement, and the combined data is presented.

Changes in the mRNA level of selected genes were confirmed at the protein level by Western blotting using standard protocols. In brief, 30 µg of whole liver proteins were analyzed from each animal, and primary antibodies raised against FAS (1:1,000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Semi-quantitative analysis of the target protein expression level was performed using ImageJ (19), with β-actin serving as a load control.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. Data from all four groups were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest to determine statistical differences between groups using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). When comparing two groups, a Student t-test was performed. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated and statistical comparisons were performed using a log-rank test. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Cd36−/− mice are resistant to the development of alcoholic steatosis

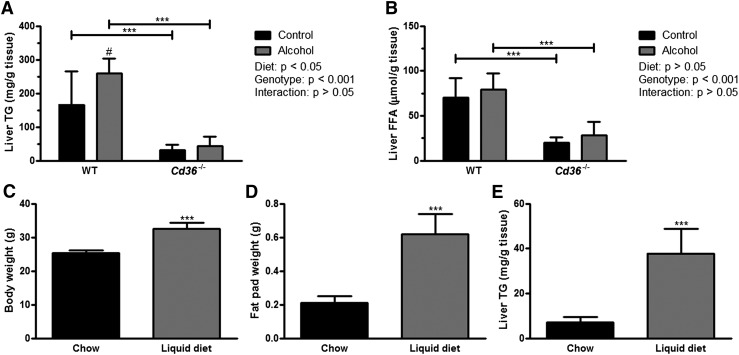

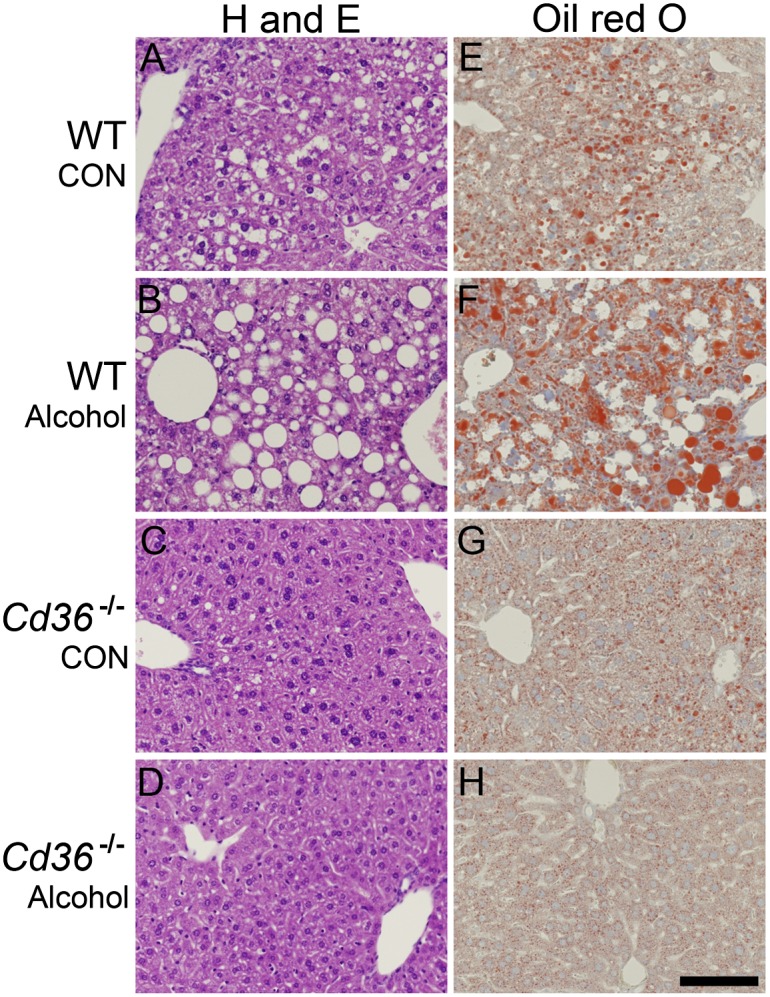

Liver and plasma samples were collected from mice fed control and alcohol-containing liquid diets for six weeks. The BAC of alcohol-fed WT (0.27% ± 0.07) and Cd36−/− (0.34% ± 0.05) mice were not significantly different, suggesting that alcohol intake and metabolism were not affected by CD36 deficiency. Histological examination of liver sections revealed the presence of numerous lipid droplets in control- and alcohol-fed WT mice, which were visible in H and E, and Oil Red O-stained sections (Fig. 1). There appeared to be larger and more numerous lipid droplets in the livers of alcohol-fed WT mice (Fig. 1B, F). Strikingly, the absence of large lipid droplets was noted in control (Fig. 1C, G) and alcohol-fed Cd36−/− mice (Fig. 1D, H). None of the livers had pronounced collagen deposition as revealed by Masson's trichrome staining (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Histology reveals pronounced steatosis in alcohol-fed WT mice but not in Cd36−/− mice. Representative microscope images from WT control (A and E), WT alcohol (B and F), Cd36−/− control (C and G), and Cd36−/− alcohol (D and H) livers are shown. The left column shows H and E staining and the right column shows Oil Red O staining. CON, control. Scale bar = 100 µm.

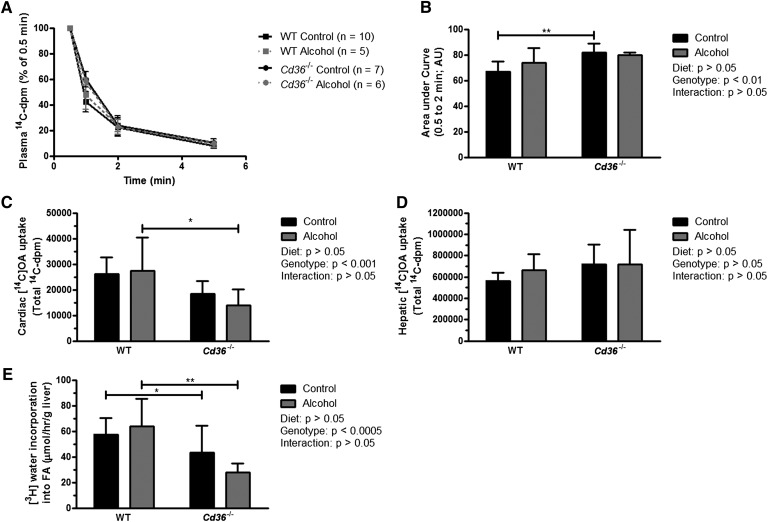

In agreement with our histology, biochemical analysis revealed a significantly higher level of hepatic TG in WT versus Cd36−/− mice fed either the control or alcohol-containing diet (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, there was an alcohol-associated increase in hepatic TG levels in WT mice that was not observed in Cd36−/− mice. Thus, Cd36−/− mice had lower baseline levels of hepatic TG relative to WT mice that did not increase following chronic alcohol consumption. We note that the significantly lower hepatic TG level in Cd36−/− mice appears to be unique to mice fed liquid diets. Although we did not directly compare hepatic TG levels in chow-fed WT and Cd36−/− mice, it has previously been reported that chow-fed Cd36−/− mice have either unchanged or higher hepatic TG levels compared with WT mice in nonfasting or fasting conditions, respectively (20, 21). In addition to lower TG levels, Cd36−/− mice also had significantly lower hepatic FFA levels than WT mice, although there was no effect of alcohol in either genotype (Fig. 2B). Similarly, hepatic TC levels were not different in alcohol-fed mice, although Cd36−/− mice had significantly lower levels of hepatic TC (supplementary Table II). Statistical analysis of the physical and biochemical characteristics of control- and alcohol-fed WT and Cd36−/− mice are reported in supplementary Table II.

Fig. 2.

Cd36−/− mice are resistant to alcohol-induced TG accumulation. Liver TG (A) and FFA (B) levels in WT and Cd36−/− mice fed control and alcohol-containing liquid diets for six weeks (n = 6/group). In a separate experiment, the body weight (C), white adipose tissue mass (D), and hepatic TG content (E) are compared in WT mice fed chow (n = 4) or a liquid diet (n = 5) for approximately three weeks. ***P < 0.001 for comparison within diets and #P < 0.05 for comparisons within genotype (A and B); ***P < 0.001 between groups (C–E).

Hepatic TG content is higher in WT mice fed a low-fat/high-carbohydrate liquid diet in the absence of alcohol compared with chow-fed mice

The hepatic TG levels observed in control- and alcohol-fed mice consuming the low-fat/high-carbohydrate liquid diets were considerably higher than expected (12, 22). To understand this finding, we compared hepatic TG levels in WT mice fed the control liquid diet with age-matched WT mice fed a chow diet in the absence of alcohol (Fig. 2). Compared with chow-fed mice, WT mice fed a liquid diet for about three weeks had a significantly greater body weight (Fig. 2C) and significantly more white adipose tissue mass (Fig. 2D), whereas liver weight was comparable and liver:body weight ratios were identical (data not shown). Furthermore, mice fed the liquid diet had ∼5-fold higher hepatic TG levels compared with chow-fed mice (P < 0.001; Fig. 2E). Thus, consumption of the low-fat/high-carbohydrate liquid diet leads to the development of hepatic steatosis in WT mice in the absence of alcohol.

Resistance to alcoholic steatosis in Cd36−/− mice is independent of FFA uptake

We predicted that impaired hepatic FFA uptake would underlie the resistance of Cd36−/− mice to develop alcoholic steatosis. In agreement with previous studies (11–13), Cd36 mRNA expression was increased in alcohol-fed WT mice (Table 1). Additionally, the mRNA expression levels of several other genes associated with hepatic FFA uptake were also assessed (Table 1). Lpl expression, which is an important partner of CD36-mediated FFA uptake into tissues (7), was significantly increased by alcohol, but only in WT mice. Moreover, Lpl mRNA levels were lower in Cd36−/− compared with WT mice, regardless of diet. No significant differences in the expression levels of the fatty acid transport proteins Fatp1, 2, and 5 were observed between all groups.

TABLE 1.

Relative hepatic gene expression levels in WT and mice fed control and alcohol-containing diets

| WT | Cd36−/− | P (Two-way ANOVA) | ||||

| Control | Alcohol | Control | Alcohol | Diet | Genotype | |

| Fatty acid uptake | ||||||

| Cd36 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.6# | ND | ND | — | — |

| Fatp1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| Fatp2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.83 | 0.2 |

| Fatp5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.34 |

| Lpla | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5# | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.3*** | 0.22 | < 0.001 |

| De novo lipogenesis | ||||||

| Acc1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.2* | 0.6 ± 0.2* | 0.75 | < 0.001 |

| Fasn | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.3* | 0.3 ± 0.2** | 0.35 | < 0.001 |

| Scd1 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.2*** | 0.2 ± 0.1** | < 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Pparg | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.1*** | 0.4 ± 0.2*** | 0.38 | < 0.001 |

| Srebp1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Triglyceride synthesis | ||||||

| Dgat1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.11 | 0.71 |

| Dgat2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.5# | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | < 0.05 | 0.07 |

| FA oxidation | ||||||

| Ppara | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| Acox1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| Cpt1a | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.91 | 0.45 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | ||||||

| Pdk4 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 2.7# | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | < 0.05 | 0.08 |

| G6pc | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

| Pepck | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.6 ± 1.9* | 0.35 | < 0.001 |

| Chrebp | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.5# | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.88 |

All data are shown relative to WT mice fed the control diet; data are mean ± SD, n = 12–13/group. #P < 0.05 for comparisons between diets within the same genotype. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 for comparisons between genotypes within the same diet; ND,= not detectable.

Significant interaction by two-way ANOVA.

The role of CD36 in alcoholic steatosis was further assessed by measuring hepatic FFA uptake in vivo. We studied mice in the nonfasting condition when hepatic FFA uptake rates have been shown to be similar between Cd36−/− and WT mice (14), rather than after overnight fasting when uptake is reported to be significantly greater in Cd36−/− mice (20). Plasma clearance of [14C]OA was delayed in Cd36−/− mice at the earlier time points after [14C]OA injection (Fig. 3A). This was also evident when expressed as the area under the plasma clearance curve for these animals (Fig. 3B). Cd36−/− mice showed decreased FFA uptake into the heart, which is in agreement with the central role of CD36 in cardiac FFA uptake (20). Alcohol had no effect on cardiac FFA uptake in WT or Cd36−/− mice (Fig. 3C). Chronic alcohol consumption had no effect on hepatic FFA uptake in Cd36−/− mice, and contrary to our hypothesis, alcohol did not increase hepatic FFA uptake in WT mice (Fig. 3D). This experiment was repeated in a separate set of mice after a 16 h fast, with similar results (data not shown). These data indicate that alcohol-induced steatosis and the protective effect of CD36 deficiency against alcoholic steatosis are independent of hepatic FFA uptake.

Fig. 3.

Hepatic FFA uptake is unaffected in Cd36−/− mice, but de novo lipogenesis is reduced. The plasma clearance curves for mice given an intravenous bolus of [14C]OA are shown (A), as well as the integrated area under the curve (B). FFA uptake into the heart (C) and liver (D) was also quantified. In a separate experiment, the rate of hepatic de novo lipogenesis (n = 6–7/ group) was quantified by measuring the amount of [3H]water incorporated into FA per hour (E). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 for comparisons within diets. AU, Arbitrary unit.

Evidence of dysregulated hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in control- and alcohol-fed mice

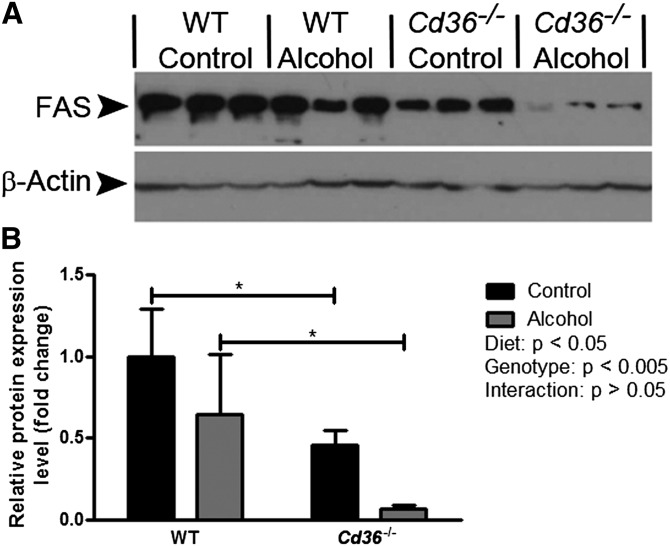

Given that our hypothesis concerning CD36 and hepatic FFA uptake was not substantiated, we expanded our analysis of hepatic gene expression levels (Table 1). Regarding FA oxidation, we found no statistically significant effect of genotype or diet on the expression of Ppara, Cpt1a, or Acox1. We next examined hepatic TG synthesis, which can be catalyzed by Dgat1 or Dgat2 (23). Alcohol feeding had no significant effect on Dgat1 expression in WT or Cd36−/− mice. Interestingly, Dgat2 expression was significantly increased by alcohol-feeding in WT mice but not in Cd36−/− mice. The most dramatic changes in gene expression levels were noted in the pathway for DNL. Critical enzymes in this pathway include Acc1, Fasn, and Scd1; strikingly, all three of these genes were significantly downregulated in Cd36−/− mice compared with WT mice in the control and alcohol-fed groups. This genotypic effect was reflected in a marked reduction in Pparg expression levels in Cd36−/− mice, which is a transcriptional regulator of Acc1, Fasn, and Scd1. We confirmed the observed decrease in genes associated with the DNL pathway at the protein level by Western blotting, analyzing FAS expression as a representative member of the DNL pathway (Fig. 4). In agreement with our qPCR data, there was a strong genotypic effect on FAS expression, with markedly decreased levels observed in Cd36−/− mice. Alcohol feeding seemed to be associated with decreased FAS expression, although posttest analyses were not significant in either genotype.

Fig. 4.

FAS expression is decreased in Cd36−/− mice. Representative images of Western blots showing bands corresponding to FAS and β-actin expression are shown (A). The relative protein expression level of FAS was determined by semi-quantitative image analysis, with β-actin serving as a reference protein (B). *P < 0.05 for comparisons within mice fed the same diet.

Although it is an important transcriptional regulator of DNL, Srebp1 expression was not significantly different between WT and Cd36−/− mice; however, there was a modest diet effect suggesting that alcohol suppressed the expression of this gene, although posttest analysis revealed no significant differences in either genotype. The final metabolic pathway we examined was hepatic carbohydrate metabolism. Our two-way ANOVA of Chrebp expression was not significant, with no apparent effect of alcohol or genotype on the expression of this gene. Our posttest analysis revealed a significant increase in Chrebp expression in WT mice only, but the biological significance of this modest effect is unclear. Interestingly, the expression level of Pdk4 (glucose oxidation) was significantly increased more than 2-fold in alcohol-consuming WT but not in Cd36−/− mice. Although G6pc (glucose synthesis) expression was not significantly different in any group, Pepck expression was significantly higher in Cd36−/− versus WT mice, suggesting increased gluconeogenesis in these animals. Taken together, our gene expression data indicate that the DNL pathway was significantly dysregulated in Cd36−/− mice, accompanied by changes in other pathways controlling hepatic energy metabolism.

Hepatic de novo lipogenesis is decreased in Cd36−/− mice

Our qPCR data indicated that the DNL pathway was dysregulated in Cd36−/− mice. To substantiate this finding, we performed kinetic studies to determine the rate of hepatic DNL (Fig. 3E). In agreement with our gene expression data, the rate of [3H]water incorporation into FA in Cd36−/− mice was significantly lower than in WT mice. We found a 37% reduction in the rate of DNL in control-fed Cd36−/− mice versus control-fed WT mice (P < 0.05), and a 56% reduction in alcohol-fed Cd36−/− mice versus alcohol-fed WT mice (P < 0.01). Despite these striking changes in DNL, there was no significant effect of chronic alcohol consumption in either genotype. These data indicate that reduced DNL is a major contributor to the reduced baseline levels of hepatic TG observed in Cd36−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

Elevated CD36 expression has been reported in the alcohol-exposed liver (11–13), which was confirmed in the present study. We hypothesized that Cd36−/− mice would be resistant to alcohol-induced steatosis and that a correlation exists between the alcohol-induced increase in hepatic Cd36 expression and increased FFA uptake. This hypothesis was tested in WT and Cd36−/− mice fed low-fat/high-carbohydrate Lieber-DeCarli liquid diets. Our data establish a protective role for CD36 deficiency in the development of alcoholic steatosis, which is clearly evidenced by the observation that Cd36−/− mice chronically fed alcohol do not develop elevated hepatic TG levels. Interestingly, we also noted that Cd36−/− mice are resistant to the lipogenic effect of consuming a high-carbohydrate liquid diet. While these data support our hypothesis that Cd36−/− mice are resistant to the development of alcoholic steatosis, the mechanism was not related to altered FA uptake, as discussed below. In this regard, our data raise two questions: what is the protective mechanism of CD36 deficiency? And, why are baseline levels of hepatic TG lower in Cd36−/− mice when fed a liquid diet?

To answer the first question, we focused on the known role of CD36 in tissue FFA uptake. Contrary to our original hypothesis, we found no effect of alcohol or CD36 deficiency on hepatic FFA uptake in vivo. Thus, although Cd36 expression was elevated by alcohol feeding in WT mice, this did not correspond to an increased rate of hepatic FFA uptake. Similarly, the rate of hepatic FFA uptake did not differ between WT and Cd36−/− mice, a finding that is consistent with the literature (14). While increased hepatic FFA uptake has been proposed to contribute to alcoholic steatosis (3, 13), this notion is largely derived from studies performed in vitro. For example, alcohol has been shown to increase [3H]OA uptake into HepG2 cells (24), and primary hepatocytes isolated from rodents chronically fed alcohol displayed increased [3H]OA uptake (11, 25). While our in vivo FFA uptake data do not support the notion that this process is a significant contributor to alcoholic steatosis, differences in experimental models complicate the interpretation of these data.

Guided by our analysis of hepatic gene expression, we formulated the alternate hypothesis that decreased DNL underlies the protective effect of CD36 deficiency against alcoholic steatosis. Our in vivo assessment of DNL led to the striking observation that control- and alcohol-fed Cd36−/− mice had significantly lower rates of hepatic DNL than their WT counterparts. These data are consistent with our hepatic gene expression data that showed a consistent downregulation of genes associated with DNL (Pparg, Acc1, Fasn, Scd1) in Cd36−/− mice. In this regard, reduced DNL may decrease the availability of ligands for PPARγ, thereby reducing its transcriptional activity and leading to a decrease in the transcription of genes important for DNL, thus creating a feedback loop reinforcing the decrease in DNL. Despite these striking differences between WT and Cd36−/− mice, we did not observe an effect of alcohol on hepatic DNL in either genotype.

With respect to alcohol's effect on hepatic DNL, there is no consensus in the literature regarding this important contributor to hepatic TG levels. While it has been reported by You et al. that alcohol increases SREBP1c expression with resultant effects on hepatic fatty acid synthesis (26, 27), others have recently reported that alcohol consumption decreases SREBP1c expression (28). Our results are in agreement with Tijburg et al. and Venkatesan et al., who conducted in vivo measures of DNL and concluded that increases in this pathway are not a major contributor to the development of alcoholic steatosis (29, 30). Although it was not the focus of our follow-up studies, we would highlight that the literature regarding alcohol's effect on the function of PPARα is also equivocal. While it has been reported that alcohol decreases hepatic expression of PPARα (31, 32), others have reported no change or increased PPARα expression in response to chronic alcohol consumption (33–35).

Our data indicate that liquid diet consumption promoted more DNL in WT mice than Cd36−/− mice. The elevated levels of hepatic TG observed in WT mice fed a liquid diet, versus chow, suggests that this diet acts like other high-carbohydrate diets that promote DNL and hepatic steatosis (36). This lipogenic effect of the low-fat/high-carbohydrate Lieber-DeCarli diet is worth highlighting as it reflects a limitation in this model. Indeed, the accumulation of hepatic TG in mice fed either the high-fat or low-fat formulation of the Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet is evident from the literature. While this phenomenon reflects an inherent bias in these models toward the development of fatty liver, it is important to emphasize that chronic alcohol consumption exacerbates this condition leading to significantly more hepatic TG accumulation in the livers of alcohol-fed mice. In this regard, our data clearly demonstrate that alcohol-fed WT mice have relatively higher hepatic TG levels than their counterparts consuming a control diet, an effect that was absent in Cd36−/− mice.

The reduced rate of hepatic DNL provides a mechanistic explanation for the reduced level of hepatic TG in Cd36−/− mice; however, the link between CD36 deficiency and DNL requires further investigation. DNL can be viewed as an important intersection between carbohydrate and lipid metabolism; not only can carbohydrates like glucose be used as a substrate for DNL, several lipogenic genes are also under control of the carbohydrate responsive transcription factor, ChREBP (37). We believe the impaired hepatic DNL in Cd36−/− mice can be explained by abnormal glucose homeostasis. In the context of impaired FA utilization, Cd36−/− mice have an increased demand for glucose to meet their energy demands (38). Indeed, previous studies have documented that hepatic glucose output is increased in Cd36−/− mice (21, 38), an effect that is consistent with the increased hepatic Pepck expression observed for Cd36−/− mice in the current study. Thus, despite increased gluconeogenesis in the liver of Cd36−/− mice, this nascent glucose is exported from the liver to help meet the energy demands of other tissues in the body. We speculate that increased glucose output from the liver could reduce glucose availability as a substrate for DNL, thus contributing to the lower hepatic TG observed in these animals. Our current working hypothesis proposes that altered hepatic glucose homeostasis contributes to the reduced rate of hepatic DNL in Cd36−/− mice, a phenomenon which is being further studied in our laboratory.

We believe that the above-mentioned dysregulation in hepatic FA and glucose metabolism in Cd36−/− mice can explain the protective effect of CD36 deficiency against alcoholic steatosis. Our analysis of hepatic gene expression indicates that Pdk4 and Dgat2 were upregulated in alcohol-fed WT mice but not in Cd36−/− mice. We speculate that increased Pdk4 expression would inhibit the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex with resultant effects on glyceroneogenesis (39, 40). This would lead to increased cellular levels of glycerol-3-phosphate, an important precursor molecule for the backbone of TG. This presumed increase in the backbone material for TG, as well as an increase in hepatic FAs, would provide ample substrate for TG synthesis. Our data show that Pdk4 gene expression levels are not elevated in alcohol-fed Cd36−/− mice and that these mice have lower hepatic FA levels; thus, in the context of chronic alcohol consumption, there is less substrate available for TG synthesis in Cd36−/− mice relative to WT mice. In agreement with the concept that TG synthesis is increased in WT mice versus Cd36−/− mice, we found that Dgat2 expression is increased in response to alcohol only in WT mice. This finding is consistent with a recent report showing that DGAT2 has an important role in the development of alcoholic steatosis (41). This increase in Dgat2 gene expression is particularly significant because it is known that DGAT2 preferentially synthesizes TG using FA derived from DNL (42, 43), a pathway that we have shown to be downregulated in Cd36−/− mice. Thus, relative to Cd36−/− mice, alcohol-fed WT mice have an increased capacity to synthesize and accumulate hepatic TG, as evidenced by increased synthetic enzymes (Dgat2) and increased substrate availability (FA and glycerol-3-phosphate).

In conclusion, Cd36−/− mice chronically fed alcohol do not develop hepatic steatosis when fed a lipogenic, low-fat/high-carbohydrate liquid diet and are further resistant to the development of alcoholic steatosis. A reduced rate of hepatic DNL was clearly responsible for the lower baseline levels of hepatic TG observed in Cd36−/− mice. Our data also indicate that alcohol-fed Cd36−/− mice had a reduced ability to synthesize TG because of a reduced enzymatic capacity to make TG, as well as reduced substrate availability for TG synthesis. Overall, these studies provide unique insight into the effects of alcohol and CD36 deficiency on hepatic lipid metabolism and the development of alcoholic steatosis, which appear to be independent of the potential role of CD36 in hepatic fatty acid uptake.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ALD

- alcoholic liver disease

- BAC

- blood alcohol content

- DNL

- de novo lipogenesis

- OA

- oleic acid

- TC

- total cholesterol

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21AA020561 (L-S.H.), R21HL112233 (L-S.H.), R01DK33301 (N.A.A.), R01HL45095 (I.J.G.), RC2AA019413 (W.S.B.), R01DK068437 (W.S.B.), R01DK079221 (W.S.B.), and R21AA021336 (W.S.B.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one figure and two tables.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rehm J., Mathers C., Popova S., Thavorncharoensap M., Teerawattananon Y., Patra J. 2009. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 373: 2223–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann R. E., Smart R. G., Govoni R. 2003. The epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res. Health. 27: 209–219 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sozio M. S., Liangpunsakul S., Crabb D. 2010. The role of lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 30: 378–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverstein R. L., Febbraio M. 2009. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci. Signal. 2: re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin C., Chevrot M., Poirier H., Passilly-Degrace P., Niot I., Besnard P. 2011. CD36 as a lipid sensor. Physiol. Behav. 105: 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su X., Abumrad N. A. 2009. Cellular fatty acid uptake: a pathway under construction. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20: 72–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg I. J., Eckel R. H., Abumrad N. A. 2009. Regulation of fatty acid uptake into tissues: lipoprotein lipase- and CD36-mediated pathways. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl.): S86–S90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J., Febbraio M., Wada T., Zhai Y., Kuruba R., He J., Lee J. H., Khadem S., Ren S., Li S., et al. 2008. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology. 134: 556–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koonen D. P., Jacobs R. L., Febbraio M., Young M. E., Soltys C. L., Ong H., Vance D. E., Dyck J. R. 2007. Increased hepatic CD36 expression contributes to dyslipidemia associated with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 56: 2863–2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greco D., Kotronen A., Westerbacka J., Puig O., Arkkila P., Kiviluoto T., Laitinen S., Kolak M., Fisher R. M., Hamsten A., et al. 2008. Gene expression in human NAFLD. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294: G1281–G1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge F., Zhou S., Hu C., Lobdell H. t., Berk P. D. 2010. Insulin- and leptin-regulated fatty acid uptake plays a key causal role in hepatic steatosis in mice with intact leptin signaling but not in ob/ob or db/db mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 299: G855–G866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clugston R. D., Jiang H., Lee M. X., Piantedosi R., Yuen J. J., Ramakrishnan R., Lewis M. J., Gottesman M. E., Huang L. S., Goldberg I. J., et al. 2011. Altered hepatic lipid metabolism in C57BL/6 mice fed alcohol: a targeted lipidomic and gene expression study. J. Lipid Res. 52: 2021–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong W., Zhao Y., Tang Y., Wei X., Shi X., Sun W., Sun X., Yin X., Kim S., McClain C. J., et al. 2012. Chronic alcohol exposure stimulates adipose tissue lipolysis in mice: role of reverse triglyceride transport in the pathogenesis of alcoholic steatosis. Am. J. Pathol. 180: 998–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Febbraio M., Abumrad N. A., Hajjar D. P., Sharma K., Cheng W., Pearce S. F., Silverstein R. L. 1999. A null mutation in murine CD36 reveals an important role in fatty acid and lipoprotein metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 19055–19062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeCarli L. M., Lieber C. S. 1967. Fatty liver in the rat after prolonged intake of ethanol with a nutritionally adequate new liquid diet. J. Nutr. 91: 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr T. P., Andresen C. J., Rudel L. L. 1993. Enzymatic determination of triglyceride, free cholesterol, and total cholesterol in tissue lipid extracts. Clin. Biochem. 26: 39–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augustus A. S., Buchanan J., Park T. S., Hirata K., Noh H. L., Sun J., Homma S., D'Armiento J., Abel E. D., Goldberg I. J. 2006. Loss of lipoprotein lipase-derived fatty acids leads to increased cardiac glucose metabolism and heart dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 8716–8723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spady D. K., Dietschy J. M. 1983. Sterol synthesis in vivo in 18 tissues of the squirrel monkey, guinea pig, rabbit, hamster, and rat. J. Lipid Res. 24: 303–315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9: 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coburn C. T., Knapp F. F., Jr, Febbraio M., Beets A. L., Silverstein R. L., Abumrad N. A. 2000. Defective uptake and utilization of long chain fatty acids in muscle and adipose tissues of CD36 knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 32523–32529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajri T., Han X. X., Bonen A., Abumrad N. A. 2002. Defective fatty acid uptake modulates insulin responsiveness and metabolic responses to diet in CD36-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 109: 1381–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid B. N., Ables G. P., Otlivanchik O. A., Schoiswohl G., Zechner R., Blaner W. S., Goldberg I. J., Schwabe R. F., Chua S. C., Jr, Huang L. S. 2008. Hepatic overexpression of hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase promotes fatty acid oxidation, stimulates direct release of free fatty acids, and ameliorates steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 13087–13099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yen C. L., Stone S. J., Koliwad S., Harris C., Farese R. V., Jr 2008. Thematic review series: glycerolipids. DGAT enzymes and triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 49: 2283–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S. L., Gordon R. E., Bradbury M., Stump D., Kiang C. L., Berk P. D. 1998. Ethanol up-regulates fatty acid uptake and plasma membrane expression and export of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in HepG2 cells. Hepatology. 27: 1064–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berk P. D., Zhou S., Bradbury M. W. 2005. Increased hepatocellular uptake of long chain fatty acids occurs by different mechanisms in fatty livers due to obesity or excess ethanol use, contributing to development of steatohepatitis in both settings. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 116: 335–344, discussion 345 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You M., Fischer M., Deeg M. A., Crabb D. W. 2002. Ethanol induces fatty acid synthesis pathways by activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP). J. Biol. Chem. 277: 29342–29347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.You M., Matsumoto M., Pacold C. M., Cho W. K., Crabb D. W. 2004. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the action of ethanol in the liver. Gastroenterology. 127: 1798–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nammi S., Roufogalis B. D. 2013. Light-to-moderate ethanol feeding augments AMPK-alpha phosphorylation and attenuates SREBP-1 expression in the liver of rats. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 16: 342–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tijburg L. B., Maquedano A., Bijleveld C., Guzman M., Geelen M. J. 1988. Effects of ethanol feeding on hepatic lipid synthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 267: 568–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesan S., Ward R. J., Peters T. J. 1987. Fatty acid synthesis and triacylglycerol accumulation in rat liver after chronic ethanol consumption. Clin. Sci. (Lond.). 73: 159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crabb D. W., Galli A., Fischer M., You M. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol. 34: 35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kong L., Ren W., Li W., Zhao S., Mi H., Wang R., Zhang Y., Wu W., Nan Y., Yu J. 2011. Activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha ameliorates ethanol induced steatohepatitis in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 10: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chavez P. R., Lian F., Chung J., Liu C., Paiva S. A., Seitz H. K., Wang X. D. 2011. Long-term ethanol consumption promotes hepatic tumorigenesis but impairs normal hepatocyte proliferation in rats. J. Nutr. 141: 1049–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luvizotto R. A., Nascimento A. F., Veeramachaneni S., Liu C., Wang X. D. 2010. Chronic alcohol intake upregulates hepatic expression of carotenoid cleavage enzymes and PPAR in rats. J. Nutr. 140: 1808–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segawa S., Wakita Y., Hirata H., Watari J. 2008. Oral administration of heat-killed Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 ameliorates alcoholic liver disease in ethanol-containing diet-fed C57BL/6N mice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 128: 371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poupeau A., Postic C. 2011. Cross-regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism via ChREBP and nuclear receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1812: 995–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyeda K., Yamashita H., Kawaguchi T. 2002. Carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP): a key regulator of glucose metabolism and fat storage. Biochem. Pharmacol. 63: 2075–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goudriaan J. R., Dahlmans V. E., Teusink B., Ouwens D. M., Febbraio M., Maassen J. A., Romijn J. A., Havekes L. M., Voshol P. J. 2003. CD36 deficiency increases insulin sensitivity in muscle, but induces insulin resistance in the liver in mice. J. Lipid Res. 44: 2270–2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nye C. K., Hanson R. W., Kalhan S. C. 2008. Glyceroneogenesis is the dominant pathway for triglyceride glycerol synthesis in vivo in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 27565–27574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadoudal T., Distel E., Durant S., Fouque F., Blouin J. M., Collinet M., Bortoli S., Forest C., Benelli C. 2008. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4: regulation by thiazolidinediones and implication in glyceroneogenesis in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 57: 2272–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z., Yao T., Song Z. 2010. Involvement and mechanism of DGAT2 upregulation in the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3158–3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi J., Lang W., Geisler J. G., Wang P., Petrounia I., Mai S., Smith C., Askari H., Struble G. T., Williams R., et al. 2012. The use of stable isotope-labeled glycerol and oleic acid to differentiate the hepatic functions of DGAT1 and -2. J. Lipid Res. 53: 1106–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wurie H. R., Buckett L., Zammit V. A. 2012. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 acts upstream of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 and utilizes nascent diglycerides and de novo synthesized fatty acids in HepG2 cells. FEBS J. 279: 3033–3047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.