Abstract

Transplantation of engineered tissue patches containing either progenitor cells or cardiomyocytes for cardiac repair is emerging as an exciting treatment option for patients with postinfarction left ventricular (LV) remodeling. The beneficial effects may evolve directly from remuscularization or indirectly through paracrine mechanisms that mobilize and/or activate endogenous progenitor cells to promote neovascularization and remuscularization, inhibit apoptosis, and attenuate LV dilatation and disease progression. Despite encouraging results, further improvements are necessary to enhance current tissue-engineering concepts and techniques and to achieve clinical impact. Herein, we review several strategies for cardiac remuscularization and paracrine support that can induce cardiac repair and attenuate LV dysfunction from both within and outside the myocardium.

Keywords: Cell Therapy, Heart Failure, Tissue Engineering, Paracrine

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure often develops as a consequence of the limited endogenous capacity for cardiac regeneration after acute myocardial infarction (MI). 1 Cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) that have been transplanted into hearts with MI can repair the damaged myocardium to some degree, despite their low engraftment rates and limited evidence of transdifferentiation into myocardial cells. 2-14 However, as progenitor- and stem cell-based tissue engineering technologies continue to evolve, it now appears possible to deposit and retain large numbers of therapeutic cells in close proximity to the region of myocardial tissue damage, and even to replace scar tissue, thus preventing scar bulging and LV dilation, reducing wall stress at the border zone (BZ) of the infarct, improving myocardial bioenergetics, and, finally, remuscularizing the heart. 15-18

Tissue-engineered cardiomyoplasty, using engineered myocardium or cell sheets, was first introduced at the beginning of the millennium19-25. Recently, the paracrine activity of the engineered tissue has been enhanced by using fibrin patches as the cell carrier. 16-18, 26 Importantly, evidence of myocardial salvage has been obtained with both the direct-remuscularization and paracrine approaches in rodent and porcine allograft models. 17, 23, 25 Paracrine factors led to significant increases in BZ vascular density and in the regeneration of myocytes from endogenous CPCs. Although these reports suggest that tissue-engineered patches could have therapeutic potential for the repair of myocardial injury, the overall engraftment rate and biophysical integration of grafts needs further optimization.

Engineering cardiac patches for heart repair is a challenging biotechnological objective. This review summarizes the progress in cardiac patch engineering (Table 1) and critically analyzes the problems and considerations that have to be incorporated into the design of an optimal engineered cardiac patch for heart-failure therapy. Despite the relatively straightforward biological rationale, the mechanisms responsible for the observed therapeutic effects are, in most cases, incompletely understood. Here, we review the available data on tissue-engineered heart repair and highlight evidence of the specific mechanisms of action associated with tissue-engineered patches.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies

| Cell Lines and Other Components | Reference | Summary/Observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Scaffolds | Collagen | Neonatal rat heart cells | Souren27,28 | Floating collagen layers were used as a matrix for CM seeding and studies of myocyte contractile behavior |

| Zimmermann29 | First introduction of EHTs from neonatal rat CMs in collagen/Matrigel matrix mixtures and demonstration of the importance of mechanical loading | |||

| Zimmermann30 | 3D EHTs show morphological, ultra-structural, and function properties of native myocardium and show distinct responses to growth factor stimulation | |||

| Naito31 | The non-myocytes and in particular fibroblasts are important for optimal EHT function and capillarization; Matrigel can be replaced by insulin and T3; fusion of individual EHTs can be employed to generate large tissue patches | |||

| Tiburcy32 | Immature CMs terminally differentiate and reach a postnatal degree of mature in EHTs | |||

| Zimmermann20 | EHTs are quickly capillarized and innervated after implantation | |||

| Zimmermann23 | Multi-loop EHTs can be used to enhance contractile performance of infarcted rat hearts | |||

| Fetal rat heart cells | Li21 | Cardiomyocytes can be seeded on gelatin sponge (Gelfoam); implanted grafts remain viable | ||

| Chick embryo heart cells | Eschenhagen 37 | First introduction of cardiomyocyte populated matrices (CMPMs) from embryonic chick cardiomyocytes in collagen gels | ||

| Fink38 | Stretching of EHTs induces hypertrophy and functional improvement | |||

| Mouse embryonic stem cells | Guo39 | Use of mouse embryonic stem cells as cardiomyocyte source for EHT construction demonstrated | ||

| Mouse parthenogenetic stem cells | Didié40 | Use of mouse parthenogenetic stem cells (PSCs) as cardiomyocyte source for engineered heart muscle (EHM) construction demonstrated; proof-of-concept for the utility of PSC-EHM in heart repair | ||

| Human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells | Tulloch41 | Human EHTs generated and cardiomyocyte proliferation observed | ||

| Soong42 | Human EHTs generated under serum-reduced conditions | |||

| Streckfuss-Bömeke43 | Different iPSC sources for cardiomyocyte derivation and EHT construction | |||

| Rat MSCs | Maureira44 | Contractility↑, perfusion↑, infarct size↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| Fibrin | Neonatal rat vascular SMCs | Ross45 | ECM gene expression correlates with tissue growth and development in fibrin gel | |

| Weinbaum46 | Evaluates a method for monitoring collagen transcription in EHTs | |||

| Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Black47 | Cell alignment improves twitch force | ||

| Human fibroblasts or rat SMCs | Long48 | Elastogenesis can be achieved in tissue engineering | ||

| Grassl49 | Fibrin stimulates collagen production by SMCs | |||

| miPSC-CMs | Liau50 | Cardiac tissue derived from pluripotent stem cells has advanced structure and function | ||

| Porcine MSCs | Liu26 | Neovascularization↑, wall thickening fraction↑ | ||

| SDF-1α | Zhang51 | Contractility↑, c-Kit+ cell homing↑ | ||

| HGF | Zhang52 | Contractility↑, neovascularization↑, LV dilation↓, scar size↓ | ||

| hESC-ECs and hESC-SMCs | Xiong17 | Contractility↑, neovascularization↑, bioenergetics↑, c-Kit+ cell homing↑, hypertrophy↓, apoptosis↓ | ||

| hiPSC-EC and hiPSC-SMC | Xiong18 | Contractility↑. neovascularization↑, ATP turnover↑, c-Kit+ cell homing↑, hypertrophy↓, apoptosis↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| Fibrin and matrigel | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Hansen53 | Introduces a simple system for constructing and evaluating EHTs | |

|

| ||||

| Alginate | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Dar54 | Evaluates methods for optimizing cell seeding and distribution in 3D scaffolds | |

| Dvir55 | Evaluation of a novel perfusion bioreactor that provides a homogenous milieu for tissue regeneration | |||

| Fibroblasts | Shapiro56 | Alginate may provide an excellent support for cell transplantation | ||

| Fetal rat cardiac cells | Leor22 | Contractility↑, angiogenesis↑, LV dilation↓ | ||

| Neonatal rat cardiac cells and gold nanowires | Dvir57 | Gold nanowires promote conductivity | ||

|

| ||||

| Alginate and omentum | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Dvir58 | Contractility↑, angiogenesis↑, scar thickness↑, LV dilation↓ | |

|

| ||||

| Injectable alginate | Calcium-crosslinked alginate | Landa59 | Contractility↑, LV dilation↓ | |

| Peptide modified (without cells) | Yu60 | Angiogenesis↑, LV function↑ | ||

| IGF-1 and HGF | Ruvinov61 | Angiogenesis↑, infarct↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| Gelatin gelfoam | Fetal rat cardiac cells | Li21 | Cardiac graft survived and formed junctions with host heart cells | |

|

| ||||

| Silk protein fibroin* | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Patra62 | Silk fibroin is suitable for cardiac-patch engineering | |

|

| ||||

| Synthetic Scaffolds | PGA | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Carrier63 | PGA introduced as synthetic material for myocardial tissue engineering |

| Bursac64 | Use of PGA seeded with cardiomyocytes as a model for cardiac electrophysiology | |||

| Polyglycerol sebacate | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Radisic65 | Mathematical modeling of oxygen consumption | |

| Engelmayr66 | Polyglycerol sebacate forms an accordion-like honeycomb scaffold that promotes heart-cell alignment and mechanical properties | |||

|

| ||||

| Injectable polyglycerol sebacate | Rabbit CMs | Ravichandran67 | Evaluates a minimally invasive technique that uses injectable polyglycerol sebacate fibers for scaffold creation | |

|

| ||||

| Poly ε-caprolactone | Mouse bone marrow cells | Fukuhara68 | Angiogenesis↑, LV function↑ | |

|

| ||||

| Decellularized hearts | PCLA | Rat SMCs | Matsubayashi69 | Contractility↑, wall thickness↑, LV dilation↓ |

|

| ||||

| Decellularized rat heart | Neonatal rat cardiac cells | Ott70 | Evaluates the use of a decellularized matrix for engineering a bioartificial heart | |

|

| ||||

| Decellularized heart | Human MPCs | Godier-Furnemont71 | Contractility↑, LV dilation↓ | |

|

| ||||

| Decellularized porcine bladder | hESC-ECs, HUVECs, mouse CMs | Turner72 | Evaluates the use of a decellularized matrix for delivering ESC-derived cardiac cells | |

|

| ||||

| Cell Sheets | Neonatal rat ventricular CMs | Haraguchi73 | Electrical coupling of CM sheets occurs rapidly | |

| Sekiya74 | Bioengineered cardiac cell sheets have intrinsic angiogenic potential | |||

| Hata75 | Evaluates a 3D cardiac patch made of cell sheets and decellularised matrix | |||

| Shimizu19 | Spontaneous, macroscopic beating is observed in subcutaneously implanted sheets | |||

| Shimizu76 | Subcutaneously implanted sheets survive for at least one year | |||

|

| ||||

| Neonatal rat CMs and rat ECs | Sekine77 | Contractility↑, angiogenesis↑, fibrosis↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| Rat adipose-derived MSCs | Miyahara24 | Contractility↑, scar size↓, LV dilation, mortality↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| Monkey stromal cells and monkey SSEA-1 and CPCs | Bel78 | Angiogenesis↑, cell engraftment rate↑ | ||

|

| ||||

| Bovine aortic endothelial cells | Kushida79 | Evaluates a temperature-responsive surface for culturing cell sheets | ||

|

| ||||

| mESC-derived cardiac cells | Masumoto80 | Contractility↑, wall thickness↑, angiogenesis↑, fibrosis↓ | ||

|

| ||||

| hESC-CMs | Stevens81 | Evaluates a novel scaffold-free human myocardial patch made of hESC-CMs | ||

|

| ||||

| hESC-CMs and ECs | Stevens82 | Cell engraftment↑ | ||

|

| ||||

| hiPSC-CMs | Matsuura83 | hiPSC-CMs can be used to create thick cardiac tissues | ||

| Lee84 | Evaluates a multiparametric imaging system that simultaneously measures action potentials and intracellular calcium-wave dynamics of cardiac cell sheets | |||

| Kawamura25 | Contractility↑, angiogenesis↑, LV dilation↓ | |||

3D: three-dimensional; CM: cardiomyocyte; CPC: cardiac progenitor cell; EC: endothelial cell; ECM: extracellular matrix; EHT: engineered heart tissue; hESC: human embryonic stem cell; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; hiPSC: human induced-pluripotent stem cell; HUVEC: human umbilical-vein endothelial cell; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1; LV: left ventricuar; miPSC: murine induced-pluripotent stem cell; MPC: mesenchymal progenitor cell; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; PCLA: ε-caprolactone-co-L-lactide reinforced with knitted poly-L-lactide; PDGF-BB: platelet-derived growth factor BB; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor 1; shRNA: small-hairpin RNA; SkM: skeletal myoblast; SMC: smooth muscle cell; SSEA-1: stage-specific embryonic antigen 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

PATCHING THE HEART WITH TISSUE-ENGINEERED MYOCARDIUM

Generating functional bioengineered human cardiac tissue for the treatment of end-stage heart disease has been a tremendous challenge for researchers and physicians alike. Tissue engineering was first proposed as a means to rebuild organs for therapeutic applications in the early 1990s85 and later extended to the cardiac field.20-22, 86 Generally, bioengineered cardiac tissue constructs can be divided into two categories: scaffold-based and scaffold-free. A number of three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds have been fabricated from natural biological materials, such as collagen, fibrin, and alginate, from naturally occurring extacellular matrix mixtures (Matrigel™) or decellularized heart matrix, and from synthetic polymers.

SCAFFOLD-BASED APPROACHES

Collagen

Collagen is the most prevalent extracellular component of the myocardium and has been used as a matrix for studying myocardial electrophysiology and contraction since the early 1990s27, 28. It is self-polymerizing at 37°C and physiological pH, can be molded into a variety of shapes, and when seeded with heart cells, the resulting matrix possesses many of the physiological characteristics of cardiac tissue29, 30, 32, 37, 41, 87. A key property of collagen hydrogel-based engineered heart muscle (EHM) is its contractile performance, which reproduces many, but not all, aspects of contractile performance in native myocardium29, 30, 37. The first EHM produced from mammalian (in this case, neonatal rat heart) cells was generated with a combination of collagen and Matrigel™ 29. Mechanical loading was subsequently identified as an important factor for tissue maturation29, 38, and direct comparisons with the development of native heart tissue identified organotypic maturation in collagen-based EHM that possessed the capacity to support hypertrophic growth32. Implantation of collagen-based EHM promoted further maturation, which was paralleled by vascularization and innervation20, 23.

One week after transplantation onto uninjured rat hearts, collagen scaffolds containing cardiomyocytes that had been generated through the controlled differentiation of human embryonic or induced-pluripotent stem cells (hESC-CMs or hiPSC-CMs, respectively), endothelial cells (ECs), and stromal cells contained vascular structures derived from the transplanted human cells and were perfused by the host animal’s coronary circulation.41 In a rat MI model, transplantation of a collagen scaffold containing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) was associated with improvements in infarct size, ventricular wall thickness, angiogenesis, perfusion, and contractile function, and with increases in the growth of myofibroblast-like tissue44. Collagen scaffolds have also been used to deliver vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) both directly, by modifying the protein to include a collagen-binding domain88, or indirectly, by seeding the scaffold with cells that have been genetically engineered to express VEGF89, thereby extending the duration of protein delivery and promoting vascular growth in infarcted myocardial tissue88.

The fusion of individual EHM rings into multi-loop constructs enables the creation of engineered tissues with, in principle, unlimited dimensionality (Figure 1)31. Implantation of a multi-loop patch two weeks after MI in rats led to sustained therapeutic benefits with enhanced regional contractility 4 weeks after engraftment23. Furthermore, an alternative pattern of EHM ring assembly can be used to generate cardiac-tissue pouches that provide restraint and contractile support to failing hearts (Figure 1)33, and in-vitro studies demonstrate that EHM rings can serve as a test bed for receptor pharmacology 29, growth factor signaling 30, 34, and target validation through the use of adenoviral transduction 35 and hypertrophic signaling 32, 90. hESC- and hiPSC-CMs can also be used to generate collagen-based EHM41, 87, 91, and parthenogenetic stem cells have recently been introduced as another source of stem cells for cardiomyocytes and myocardial tissue engineering 40. Further advances in collagen-based myocardial tissue will likely involve biomimetic culture platforms that incorporate electrical36 and mechanical stimulation29.

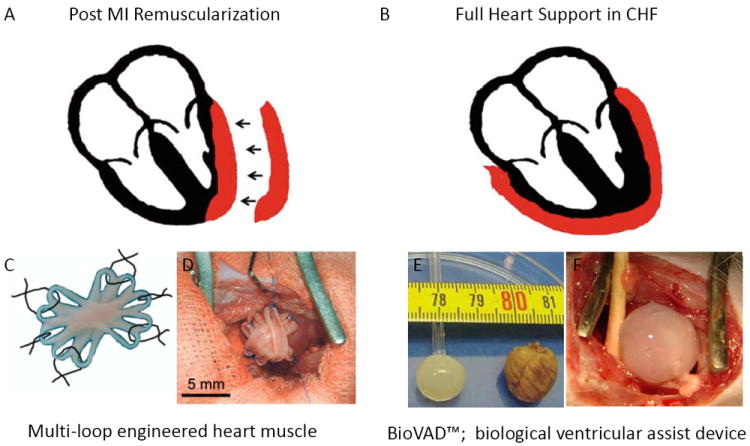

Figure 1.

Applications of engineered heart muscle (EHM). Schematic presentation of (A) an EHM patch and (B) an EHM pouch (red). (C) Illustration of a multi-loop EHM with five loops fused together to form an asterisk-shaped stack with a solid center surrounded by 10 loops that are used for surgical fixation of the EHM graft. (D) The patch was fixed over the site of infarction in rats with six single-knot sutures. (E) The dimensions of an EHM pouch and an explanted rat heart are shown. (F) An EHM pouch was implanted over a healthy rat heart to simulate its use as a biological ventricular assist device. Panels C and D are modified from Zimmermann et al. Nat Med. 2006; 12(4): 452-823; panels E and F are modified from Yildirim et al. Circulation 2007;116(11 Suppl): I16-2333.

Fibrin

Fibrinogen is cleaved and cross-linked by exposure to thrombin and clotting factor XIII to form an insoluble fibrin mesh that captures blood cells to form a blood clot. Fibrin meshes can also be used to capture any target cell for tissue engineering. In vivo, fibrin attracts leukocytes and, in particular, macrophages, and is slowly lysed by endogenous proteases. Anisotropic alignment of rat neonatal cardiac cells in fibrin scaffolds was associated with increases in twitch force, despite declines in total collagen and protein content47. Fibrinogen can also be conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to generate scaffolds that covalently bind growth factors and other proteins51, 52, and drug screening platforms have recently been established with fibrin-based engineered heart tissue53, 92. In a mouse MI model, treatment with a PEGylated fibrin patch containing stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) was associated with increases in CPC recruitment and improvements in infarct size and cardiac function; the patch was placed over the site of infarction, where it was associated with increases in SDF-1 levels for up to 28 days51.

Fibrin patches with defined biophysical properties can be created by mixing solutions of fibrinogen and thrombin, and because the mixture typically solidifies in less than one minute, the patch can be created in situ by injecting the two solutions into a mold placed over the infarct site. This method has been used to deliver autologous MSCs to swine26, and hESC-derived vascular cells (hESC-VCs) (i.e., smooth-muscle cells [SMCs] and ECs) to both swine and mice17, 18, 24, after experimentally induced MI. The transplanted MSCs differentiated into myocyte-like cells8 and were associated with greater thickening of the infarcted wall during contraction, while the hESC-VC treatments were associated with improvements in myocardial function, perfusion, and energy metabolism, and with declines in left-ventricular wall stress and remodeling.93 Furthermore, the proportion of cells retained in the ischemic region was significantly higher when the cells were administered via a patch than when injected directly into the myocardium.93 Thus, a fibrin patch can be used as a unique platform for cell delivery.

Other 3D Biological Scaffolds

Other 3D biomaterials that have been used to engineer myocardial tissue equivalents include alginates54, 56 and silks62. However, preformed matrices do not appear to be ideally suited for the assembly of cardiomyocytes into a functional 3D cardiac syncytium of contracting cells because the rigid structures/pores of the matrix isolate the cardiomyocytes from each other, thereby preventing direct intracellular contact. This caveat also applies to preformed collagen/gelatin sponges; however, gold nanowires have been used to improve the synchronous excitation of engineered cardiac tissue by bridging the electrically resistant pore walls of alginate.57 In addition, it seems essential that the exogenous matrix be rapidly replaced to prevent interference with tissue formation. Vascularization of the matrix occurs quickly in conjunction with the immune response to the presence of foreign materials.

Decellularized Matrix

Recellularization of a previously decellularized rat heart was successfully attempted in 2008, which suggests that whole organs can be reengineered by using a natural ECM blueprint70. Natural scaffolds made from decellularized porcine small-intestinal submucosa (SIS)75 and bladders72 and from human myocardial tissues71 have been used to generate 3D cardiac patches. For example, decellularized SIS has been layered with multiple sheets of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes to produce patches of up to 800-μm thickness, resulting in cardiac muscle constructs that contracted synchronously for up to 10 days75. Cell sheets broke apart when applied to decellularized bladder matrix, presumably because of the roughness of the matrix surface, but remained intact and proliferative when the voids of the matrix were filled with hyaluronan hydrogel; the hydrogel also enabled a greater number of cells to be seeded. Hydrogels made of fibrin and containing suspended human mesenchymal progenitor cells have been applied to decellularized sheets of human myocardium71 to create cardiac patches that were subsequently evaluated in a nude-rat model of MI. The patches dramatically increased both the recruitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells and vascular growth in the infarcted region, and measurements of contractility and left ventricular (LV) dimensions were similar to those obtained in uninjured hearts; integration of the patch with the myocardium of the recipient heart was not examined.

Synthetic Polymers

Polygycolic acid (PGA)68, poly ε-caprolactone-co-l-lactide (PCLA)69, poly-glycerolsebacate (PGS)66, and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)94 have been extensively used as tissue engineering substrates. These materials typically must be coated with extracellular matrix proteins to enable cardiomyocyte attachment and have many of the same limitations associated with biological matrices (as described above) for heart-muscle engineering on a macroscopic scale. However, they may be well suited for depositing cells with paracrine activity onto the heart and for providing structural support to prevent further ventricular dilatation.

Injectable Systems

Injectable scaffolds have been used to prevent LV wall thinning and bulging of the ischemic myocardium, to inhibit LV remodeling59 and to promote angiogenesis by recruiting endogenous CPCs60, 61. The injection of a cell-free, in situ–forming, alginate hydrogel into recent (7 days) and old infarcts (60 days) provided a temporary scaffold that attenuated adverse cardiac remodeling and improved contractility, and the benefits were comparable to those obtained with the intramyocardial injection of neonatal cardiomyocytes59. Angiogenesis can be enhanced by integrating RGD motifs into an alginate hydrogel60, and similar results were obtained with alginate scaffolds that had been loaded with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)61. In a rat model of acute MI, intramyocardial injections of the affinity-bound IGF-1/HGF alginate biomaterial increased angiogenesis and mature blood vessel formation at the infarct, preserved scar thickness, attenuated infarct expansion, and reduced scar fibrosis after 4 weeks. In an alternative approach, cardiomyocyte retention was improved when the cells were co-injected with nanofibers made of poly-glycerolsebacate (PGS)67.

SCAFFOLD-FREE APPROACHES

The development of scaffold-free cell sheets first became practical after the invention of a temperature-responsive polymer substrate, poly-(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PIPAAm)95. Cardiomyocyte cell sheets are grown on the polymer, released by a drop in temperature, and then stacked to yield multilayered tissues19, 79, 96. Electrical connections between cardiomyocyte sheets form quickly, probably because, in contrast to enzymatic sheet release, the temperature responsive plates leave all surface protein structures intact, thus facilitating gap junction formation73. Capillary growth can be induced by creating stacks composed of both cardiomyocyte and ECs77,74, and engrafted cell sheets survived and remained contractile for up to 1 year after implantation76. Other scaffold-free tissue engineering approaches include the construction of cardiac microtissues by using a hanging drop method or spontaneous aggregation.81, 97 Both cell-sheet and cell-aggregation technologies have been successfully used with cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells25, 80, 81, 83, 84, and recently, composite cell sheets consisting of monkey adipose-derived stromal cells and monkey ESC-derived SSEA-1+ cells were tested in vivo with encouraging results78. Thus, cell sheet-based cardiac tissue engineering may prove to be a useful strategy for cardiovascular tissue repair that suppresses LV dilatation, increases wall thickness, and improves LV chamber function.

MYOCYTE TURNOVER

The concept of cardiomyocyte turnover in the adult heart is relatively new, and whether the limited regenerative capacity of the adult heart is mediated by the proliferation of pre-existing cardiomyocytes or through the activity and derivatives of endogenous CPCs remains a matter of intense debate. 98-108 Several markers can be used to identify endogenous CPCs with cardiogenic potential, including c-Kit2, 3, Sca-114, 109, Abcg2110 and Isl1 111, 112. Once the types of CPCs are fully characterized, and their pathways of activation are deciphered, biomaterial patches can be designed to promote CPC activation and cardiomyocyte turnover, and then placed over the site of myocardial injury, leading to the more comprehensive activation of mechanisms for myocyte regeneration both within and outside the myocardium.

PATCH-ASSOCIATED PARACRINE SUPPORT in MYOCARDIAL PROTECTION and the ACTIVATION OF ENDOGENOUS REPAIR MECHANISMS

Cell Patch- and Paracrine Support-induced Myocardial Repair from Endogenous Cardiac Progenitor Cells

Although CPCs that have been transplanted into hearts after MI can repair the damaged myocardium to some degree, this activity is limited because the engraftment rate is low and trans-differentiation of the engrafted cells occurs even less frequently.4-10 Thus, myocyte regeneration from the transplanted cells has been suboptimal11-14, and additional benefits might be obtained by applying a fabricated cell patch over the periscar BZ to mobilize endogenous repair mechanisms, stabilize the chronically evolving infarct scar, reduce BZ wall stress, and improve myocardial bioenergetics. The Zhang group used a fibrin patch to enhance delivery of hESC-VCs for myocardial repair. 17 The hESC-VCs that were loaded into the patch released a variety of cytokines that promote angiogenesis and survival, and reduce apoptosis. 17, 93 Both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that the hESC-VCs effectively inhibited myocyte apoptosis, and the patch-enhanced delivery of hESC-VCs alleviated abnormalities in BZ myocardial perfusion, contractile dysfunction, and LV wall stress. These results were also accompanied by the pronounced recruitment of endogenous c-kit+ cells to the injury site, and were directly associated with a remarkable improvement in myocardial energetics, as measured by a novel in vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy method. Similar findings were obtained with fibrin patches containing VCs derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) 18. Four weeks after MI and treatment, LV structural and functional abnormalities were less severe in hearts that received the patch-enhanced celltherapy, and these improvements were accompanied by significant reductions in infarct size18. hiPSC-VC transplantation also mobilized endogenous progenitor cells into the BZ, attenuated regional wall stress, stimulated neovascularization, and improved BZ perfusion, which led to marked increases in BZ contractile function and ATP turnover rate18.

Cytokine-associated Myocardial Protection and Increased Density of Myocardial Resistant Vessels

It is a rather consistent finding in the literature that,1) only a very small percentage of transplanted cells show long term engraftment in the recipient myocardium8, 113, 114, and 2) that an even smaller fraction of the engrafted CPCs trans-differentiate into cardiomyocytes or VCs8, 113, 114. These findings have led to the belief that early paracrine interactions between the transplanted cells and native cardiomyocytes, VCs, and/or (possibly) cardiac and vascular progenitor cells provide much of the benefit associated with cell transplantation115, 116. Indeed, many reports indicate that cell transplantation performed shortly after an ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) event is associated with early declines in apoptosis of the injured cardiomyocytes. This sparing of native cardiomyocytes that would otherwise have died after the initial I-R insult likely reduced the size of the infarct and led to the subsequent declines in LV remodeling and dysfunction that were observed in cell-treated animals8, 10. Furthermore, evidence reported by Yamashita’s group indicates that cardiomyocytes may be the main source of VEGF in cardiac-tissue sheets80; they found that the omission of cardiomyocytes from transplanted sheets led to the disappearance of neovascularization and functional improvement, suggesting that the beneficial effects of the sheet were induced by cardiomyocyte-secreted cytokines.

Although these findings support the view that paracrine effects initiated by the engrafted cells contribute to declines in infarct size by decreasing apoptosis when the therapy closely follows the ischemic event, cardiomyocyte apoptosis may also be reduced at later time points, and if so, this decline may result from the somewhat delayed increase in BZ capillary density after cell-patch transplantation8, 10, 117. The patch-enhanced delivery of hESC-VCs and hiPSC-VCs was accompanied by significant improvements in myocardial perfusion in both the infarct and the BZ as well as a significant increase in the number of resistant vessels in the myocardium, which suggests that vessels generated by the transplanted, stem-cell derived VCs were functional17, 18. Furthermore, these vessels are the smallest muscular arterioles (50 ~150 μm) that regulate myocardial perfusion, and each arteriole supports capillaries where the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs. Thus, since it has been previously reported that LV hypertrophy and failure is associated with subendocardial ischemia during elevated cardiac work states118, 119, this increase in resistant-vessel density could provide the structural basis for the increases in myocardial blood flow, declines in apoptosis, and improvements in LV contractile performance that have been observed in preclinical and clinical studies17, 120-122.

CONCLUSION and FUTURE WORKS

Acute myocardial damage is exacerbated by chronic myocardial overload and LV dilatation, which often leads to heart failure. Consequently, the goal for future regenerative/reparative cardiac therapies includes at least two components: 1) minimizing oxidative myocardial damage and remodeling secondary to LV chamber dilatation, and 2) rebuilding the muscle of infarcted and chronically failing hearts to improve contractile performance. Although the paracrine mechanisms induced by cytokine administration may be well suited for delaying and preventing pathological remodeling and disease progression, the repair of significant ventricular scar bulging will likely require the generation of new cardiac muscle. Thus, strategies that combine the administration of paracrine factors with the creation and integration of engineered cardiac tissue are particularly attractive for the treatment of LV dilatation in hearts with postinfarction LV remodeling.

The beneficial effects of engineered cardiac tissue patches have been clearly demonstrated in animal models, and the clinical feasibility of this approach is supported by the successful transplantation of collagen sponges that lack cardiomyocytes123, 124 and of cell sheets that contain skeletal myoblasts125. Nevertheless, cardiac patches have yet to be extensively investigated in clinical studies, primarily because suitable sources for human cardiomyocytes are lacking. The availability of human stem cells, including hiPSCs, and highly efficient protocols for directing differentiation15, 126, 127 could alleviate this scarcity and may enable patients to be treated with patches engineered from their own cells,15, 127 thereby minimizing the potential complications that could evolve from the induction of the immune and inflammatory responses. However, the time required to generate hiPSC-CMs precludes their use in patients who need prompt treatment; thus, many patients who are candidates for cardiac-patch therapy will benefit from the continued development of patches that contain allogenic cell lines.

Cardiac patch therapy can only be successful if the patch quickly becomes integrated and perfused by the recipient’s coronary circulation. Although current tissue engineering platforms are rapidly vascularized, and many interventions can successfully promote neovascularization in the myocardium over time, the vessels may not develop quickly enough to prevent a significant fraction of the cardiomyocytes in the patch from initiating necrotic processes and apoptosis, which can occur within 30 minutes of exposure to no flow ischemia. Furthermore, the engineered tissue is less mature than the recipient myocardium, so endogenous mechanisms for sensing and responding to hypoxic conditions within the patch may not be activated by the absence of immediate vascular support. Thus, the integrity and function of the transplanted patch may be improved by the addition of factors that stimulate vessel growth, impede apoptosis, and promote graft maturation.

Engineered cardiac-tissue patches possessing both contractile and paracrine activity have been successfully applied in acute and subacute models of myocardial injury, and patches designed to promote CPC activity and/or cardiomyocyte turnover could be placed over the injury site to stimulate cardiomyocyte regeneration both at the myocardial surface and within the tissue (Figure 2). This strategy can also be extended to include the creation of engineered cardiac-tissue pouches that provide paracrine and contractile support over the entire ventricular surface (Figure 1). However, the clinical acceptance of any patch-based therapy will require the development of a practical and minimally invasive delivery method; for example, an endoscope/catheter-based system could be used to access the pericardial sac through the abdomen and diaphragm, and then solutions could be injected through the catheter to form a hydrogel-based patch in situ. Collectively, these advancements could lead to the development of a new generation of patch-based cellular therapies that combine paracrine support and remuscularization to promote cardiac repair both from within and from outside the myocardial tissue.

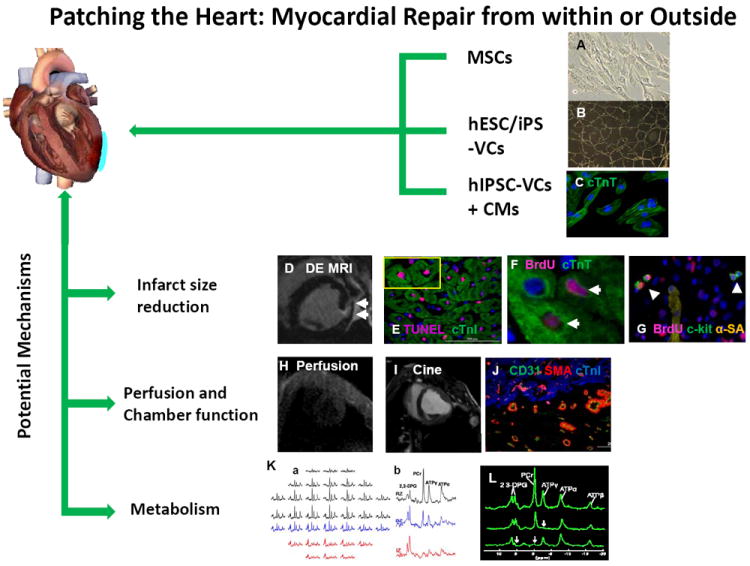

Figure 2.

The benefits associated with our in vivo method for cardiac patch application. A circular 3D porous biodegradable cardiac patch (blue) is created over the infarcted region by mixing thrombin and fibrinogen solutions that contain different progenitor cell types, such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), vascular cells (VCs) generated through the controlled differentiation of either human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), or both hiPSC-VCs and cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs). The fibrinogen can be modified to bind peptides for different purposes, such as guiding differentiation or impeding apoptosis. The solution typically solidifies in less than one minute to form a 3D porous cardiac patch that provides structural support as well as a platform for the transplanted progenitor cells, and ultimately increases the cell engraftment rate. The transplanted cells release growth factors and other cytokines that reduce apoptosis, promote angiogenesis, and activate endogenous mechanisms for cardiomyocyte renewal, which leads to declines in infarct size and to improvements in myocardial perfusion, metabolism, and contractile function. Measurements of in vivo myocardial bioenergetics and the ATP turnover rate (via 31P magnetization saturation transfer) suggest that the patch also protects against adverse changes in cardiomyocyte energy metabolism, perhaps by reducing wall stress and bulging at the site of the infarction. Collectively, these benefits improve cardiac contractile function and impede the progression of LV dilatation. (Panels B and K courtesy of Xiong Q et al Circ Res. 2012 ;111(4):455-68; Panels F, G, I, J and L, courtesy of Xiong Q et al Circulation 2013; 127(9): 997-1008).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank W. Kevin Meisner for his editorial assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

FUNDING SOURCES:

This work was supported by US Public Health Service grants NIH RO1 HL67828, HL95077, HL114120, UO1 HL100407.

W.H.Z. is supported by the DZHK (German Center for Cardiovascular Research), German Federal Ministry for Science and Education (BMBF FKZ 01GN0827, FKZ 01GN0957), the German Research Foundation (DFG ZI 708/7-1, 8-1, 10-1, SFB 1002), European Union FP7 CARE-MI, CIRM/BMBF FKZ 13GW0007A, and NIH U01 HL099997.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 3D

three dimension

- Abcg2

ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2

- BLI

bioluminescent imaging

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- BZ

border zone

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CPC

cardiac progenitor cell

- c-Kit

stem cell growth factor receptor

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EHM

engineered heart muscle

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HEP

high energy phosphates

- hESC

human embryonic stem cell

- hESC-CM

human embryonic stem cells derived cardiomyocyte

- hESC-VC

human embryonic stem cells derived vascular cell

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- hiPSC-CM

human induced pluripotent stem cells derived cardiomyocyte

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor 1

- I/R

ischemia reperfusion

- I-R

ischemia-reperfusion

- IZ

infarct zone

- Luc

firefly luciferase

- LV

left ventricular

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- PCL

poly ε-caprolactone

- PCLA

poly ε-caprolactone-co-l-lactide

- PDGF-BB

platelet derived growth factor-BB

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PGA

polygycolic acid

- PGF

poly(glycerol sebacate)

- PGS

poly-glycerol-sebacate

- PIPAAM

poly-(N-isopropylacrylamide)

- RGD

arginine-glycine-asparagine

- RZ

remote zone

- Sca-1

stem cell antigen-1

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- SIS

small-intestinal submucosa

- SkM

skeletal myoblasts

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- SSEA-1

stage-specific embryonic antigen-1

- VC

vascular cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE:

None

References

- 1.McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. Heart failure. Lancet. 2005;365:1877–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller-Ehmsen J, Whittaker P, Kloner RA, Dow JS, Sakoda T, Long TI, Laird PW, Kedes L. Survival and development of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transplanted into adult myocardium. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2002;34:107–116. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murry CE, Whitney ML, Laflamme MA, Reinecke H, Field LJ. Cellular therapies for myocardial infarct repair. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2002;67:519–526. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinecke H, Murry CE. Taking the death toll after cardiomyocyte grafting: A reminder of the importance of quantitative biology. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2002;34:251–253. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105:93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng L, Hu Q, Wang X, Mansoor A, Lee J, Feygin J, Zhang G, Suntharalingam P, Boozer S, Mhashilkar A, Panetta CJ, Swingen C, Deans R, From AH, Bache RJ, Verfaillie CM, Zhang J. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of bone marrow-derived multipotent progenitor cell transplantation in hearts with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2007;115:1866–1875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang XL, Rokosh G, Sanganalmath SK, Yuan F, Sato H, Mu J, Dai S, Li C, Chen N, Peng Y, Dawn B, Hunt G, Leri A, Kajstura J, Tiwari S, Shirk G, Anversa P, Bolli R. Intracoronary administration of cardiac progenitor cells alleviates left ventricular dysfunction in rats with a 30-day-old infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:293–305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.871905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Jameel MN, Li Q, Mansoor A, Qiang X, Swingen C, Panetta C, Zhang J. Stem cells for myocardial repair with use of a transarterial catheter. Circulation. 2009;120:S238–246. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.885236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatzistergos KE, Quevedo H, Oskouei BN, Hu Q, Feigenbaum GS, Margitich IS, Mazhari R, Boyle AJ, Zambrano JP, Rodriguez JE, Dulce R, Pattany PM, Valdes D, Revilla C, Heldman AW, McNiece I, Hare JM. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells stimulate cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Circulation research. 2010;107:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouquet F, Pfister O, Jain M, Oikonomopoulos A, Ngoy S, Summer R, Fine A, Liao R. Restoration of cardiac progenitor cells after myocardial infarction by self-proliferation and selective homing of bone marrow-derived stem cells. Circulation research. 2005;97:1090–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194330.66545.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfister O, Mouquet F, Jain M, Summer R, Helmes M, Fine A, Colucci WS, Liao R. Cd31- but not cd31+ cardiac side population cells exhibit functional cardiomyogenic differentiation. Circulation research. 2005;97:52–61. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173297.53793.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Hu Q, Nakamura Y, Lee J, Zhang G, From AH, Zhang J. The role of the sca-1+/cd31- cardiac progenitor cell population in postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1779–1788. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye L, Zhang S, Greder L, Dutton J, Keirstead SA, Lepley M, Zhang L, Kaufman D, Zhang J. Effective cardiac myocyte differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells requires vegf. PloS one. 2013;8:e53764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye L, Xiong Q, Zhang P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Zhang J, Kamp TJ, Kaufman D, Zhang J. Transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cells derived cardiac cells for cardiac repair [abstract] Circulation. 2012;126:A16457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, Lepley M, Swingen C, Zhang L, Kaufman DS, Zhang J. Bioenergetic and functional consequences of cellular therapy: Activation of endogenous cardiovascular progenitor cells. Circulation research. 2012;111:455–468. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, Lepley M, Tian J, Li J, Zhang L, Swingen C, Vaughan JT, Kaufman DS, Zhang J. Functional consequences of human induced pluripotent stem cell therapy: Myocardial atp turnover rate in the in vivo swine heart with postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 2013;127:997–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu T, Yamato M, Isoi Y, Akutsu T, Setomaru T, Abe K, Kikuchi A, Umezu M, Okano T. Fabrication of pulsatile cardiac tissue grafts using a novel 3-dimensional cell sheet manipulation technique and temperature-responsive cell culture surfaces. Circulation research. 2002;90:e40. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann WH, Didie M, Wasmeier GH, Nixdorff U, Hess A, Melnychenko I, Boy O, Neuhuber WL, Weyand M, Eschenhagen T. Cardiac grafting of engineered heart tissue in syngenic rats. Circulation. 2002;106:I151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li RK, Jia ZQ, Weisel RD, Mickle DA, Choi A, Yau TM. Survival and function of bioengineered cardiac grafts. Circulation. 1999;100:II63–69. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leor J, Aboulafia-Etzion S, Dar A, Shapiro L, Barbash IM, Battler A, Granot Y, Cohen S. Bioengineered cardiac grafts: A new approach to repair the infarcted myocardium? Circulation. 2000;102:III56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Wasmeier G, Didie M, Naito H, Nixdorff U, Hess A, Budinsky L, Brune K, Michaelis B, Dhein S, Schwoerer A, Ehmke H, Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue grafts improve systolic and diastolic function in infarcted rat hearts. Nature medicine. 2006;12:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nm1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyahara Y, Nagaya N, Kataoka M, Yanagawa B, Tanaka K, Hao H, Ishino K, Ishida H, Shimizu T, Kangawa K, Sano S, Okano T, Kitamura S, Mori H. Monolayered mesenchymal stem cells repair scarred myocardium after myocardial infarction. Nature medicine. 2006;12:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Miki K, Saito A, Fukushima S, Higuchi T, Kawamura T, Kuratani T, Daimon T, Shimizu T, Okano T, Sawa Y. Feasibility, safety, and therapeutic efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte sheets in a porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Circulation. 2012;126:S29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Hu Q, Wang Z, Xu C, Wang X, Gong G, Mansoor A, Lee J, Hou M, Zeng L, Zhang JR, Jerosch-Herold M, Guo T, Bache RJ, Zhang J. Autologous stem cell transplantation for myocardial repair. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2004;287:H501–511. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00019.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souren JE, Schneijdenberg C, Verkleij AJ, Van Wijk R. Factors controlling the rhythmic contraction of collagen gels by neonatal heart cells. In vitro cellular & developmental biology : journal of the Tissue Culture Association. 1992;28A:199–204. doi: 10.1007/BF02631092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souren JE, Peters RC, Van Wijk R. Collagen gels populated with rat neonatal heart cells can be used for optical recording of rhythmic contractions which also show ecg-like potentials. Experientia. 1994;50:712–716. doi: 10.1007/BF01919368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann WH, Fink C, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, Eschenhagen T. Three-dimensional engineered heart tissue from neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2000;68:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmermann WH, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, Didie M, Munzel F, Heubach JF, Kostin S, Neuhuber WL, Eschenhagen T. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circ Res. 2002;90:223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naito H, Melnychenko I, Didie M, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, Rosenkranz S, Eschenhagen T, Zimmermann WH. Optimizing engineered heart tissue for therapeutic applications as surrogate heart muscle. Circulation. 2006;114:I72–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiburcy M, Didie M, Boy O, Christalla P, Doker S, Naito H, Karikkineth BC, El-Armouche A, Grimm M, Nose M, Eschenhagen T, Zieseniss A, Katschinksi DM, Hamdani N, Linke WA, Yin X, Mayr M, Zimmermann WH. Terminal differentiation, advanced organotypic maturation, and modeling of hypertrophic growth in engineered heart tissue. Circulation research. 2011;109:1105–1114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.251843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildirim Y, Naito H, Didie M, Karikkineth BC, Biermann D, Eschenhagen T, Zimmermann WH. Development of a biological ventricular assist device: Preliminary data from a small animal model. Circulation. 2007;116:I16–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vantler M, Karikkineth BC, Naito H, Tiburcy M, Didie M, Nose M, Rosenkranz S, Zimmermann WH. Pdgf-bb protects cardiomyocytes from apoptosis and improves contractile function of engineered heart tissue. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;48:1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Armouche A, Singh J, Naito H, Wittkopper K, Didie M, Laatsch A, Zimmermann WH, Eschenhagen T. Adenovirus-delivered short hairpin rna targeting pkcalpha improves contractile function in reconstituted heart tissue. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2007;43:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radisic M, Park H, Shing H, Consi T, Schoen FJ, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Functional assembly of engineered myocardium by electrical stimulation of cardiac myocytes cultured on scaffolds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:18129–18134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407817101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eschenhagen T, Fink C, Remmers U, Scholz H, Wattchow J, Weil J, Zimmermann W, Dohmen HH, Schafer H, Bishopric N, Wakatsuki T, Elson EL. Three-dimensional reconstitution of embryonic cardiomyocytes in a collagen matrix: A new heart muscle model system. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1997;11:683–694. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.8.9240969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fink C, Ergun S, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, Eschenhagen T. Chronic stretch of engineered heart tissue induces hypertrophy and functional improvement. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2000;14:669–679. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo XM, Zhao YS, Chang HX, Wang CY, E LL, Zhang XA, Duan CM, Dong LZ, Jiang H, Li J, Song Y, Yang XJ. Creation of engineered cardiac tissue in vitro from mouse embryonic stem cells. Circulation. 2006;113:2229–2237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Didie M, Christalla P, Rubart M, Muppala V, Doker S, Unsold B, El-Armouche A, Rau T, Eschenhagen T, Schwoerer AP, Ehmke H, Schumacher U, Fuchs S, Lange C, Becker A, Tao W, Scherschel JA, Soonpaa MH, Yang T, Lin Q, Zenke M, Han DW, Scholer HR, Rudolph C, Steinemann D, Schlegelberger B, Kattman S, Witty A, Keller G, Field LJ, Zimmermann WH. Parthenogenetic stem cells for tissue-engineered heart repair. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1285–1298. doi: 10.1172/JCI66854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Razumova MV, Korte FS, Regnier M, Hauch KD, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Growth of engineered human myocardium with mechanical loading and vascular coculture. Circulation research. 2011;109:47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soong PL, Tiburcy M, Zimmermann WH. Cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and their assembly into engineered heart muscle. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. Chapter 23(Unit23):28. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2308s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Streckfuss-Bomeke K, Wolf F, Azizian A, Stauske M, Tiburcy M, Wagner S, Hubscher D, Dressel R, Chen S, Jende J, Wulf G, Lorenz V, Schon MP, Maier LS, Zimmermann WH, Hasenfuss G, Guan K. Comparative study of human-induced pluripotent stem cells derived from bone marrow cells, hair keratinocytes, and skin fibroblasts. Eur Heart J. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maureira P, Marie PY, Yu F, Poussier S, Liu J, Groubatch F, Falanga A, Tran N. Repairing chronic myocardial infarction with autologous mesenchymal stem cells engineered tissue in rat promotes angiogenesis and limits ventricular remodeling. Journal of biomedical science. 2012;19:93. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross JJ, Tranquillo RT. Ecm gene expression correlates with in vitro tissue growth and development in fibrin gel remodeled by neonatal smooth muscle cells. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2003;22:477–490. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinbaum JS, Qi J, Tranquillo RT. Monitoring collagen transcription by vascular smooth muscle cells in fibrin-based tissue constructs. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:459–467. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Black LD, 3rd, Meyers JD, Weinbaum JS, Shvelidze YA, Tranquillo RT. Cell-induced alignment augments twitch force in fibrin gel-based engineered myocardium via gap junction modification. Tissue engineering Part A. 2009;15:3099–3108. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long JL, Tranquillo RT. Elastic fiber production in cardiovascular tissue-equivalents. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:339–350. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grassl ED, Oegema TR, Tranquillo RT. Fibrin as an alternative biopolymer to type-i collagen for the fabrication of a media equivalent. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2002;60:607–612. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liau B, Christoforou N, Leong KW, Bursac N. Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac tissue patch with advanced structure and function. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9180–9187. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang G, Nakamura Y, Wang X, Hu Q, Suggs LJ, Zhang J. Controlled release of stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha in situ increases c-kit+ cell homing to the infarcted heart. Tissue engineering. 2007;13:2063–2071. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang G, Hu Q, Braunlin EA, Suggs LJ, Zhang J. Enhancing efficacy of stem cell transplantation to the heart with a pegylated fibrin biomatrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1025–1036. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansen A, Eder A, Bonstrup M, Flato M, Mewe M, Schaaf S, Aksehirlioglu B, Schwoerer AP, Uebeler J, Eschenhagen T. Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circulation research. 2010;107:35–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dar A, Shachar M, Leor J, Cohen S. Optimization of cardiac cell seeding and distribution in 3d porous alginate scaffolds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;80:305–312. doi: 10.1002/bit.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dvir T, Benishti N, Shachar M, Cohen S. A novel perfusion bioreactor providing a homogenous milieu for tissue regeneration. Tissue engineering. 2006;12:2843–2852. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shapiro L, Cohen S. Novel alginate sponges for cell culture and transplantation. Biomaterials. 1997;18:583–590. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dvir T, Timko BP, Brigham MD, Naik SR, Karajanagi SS, Levy O, Jin H, Parker KK, Langer R, Kohane DS. Nanowired three-dimensional cardiac patches. Nature nanotechnology. 2011;6:720–725. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dvir T, Kedem A, Ruvinov E, Levy O, Freeman I, Landa N, Holbova R, Feinberg MS, Dror S, Etzion Y, Leor J, Cohen S. Prevascularization of cardiac patch on the omentum improves its therapeutic outcome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14990–14995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812242106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Landa N, Miller L, Feinberg MS, Holbova R, Shachar M, Freeman I, Cohen S, Leor J. Effect of injectable alginate implant on cardiac remodeling and function after recent and old infarcts in rat. Circulation. 2008;117:1388–1396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu J, Gu Y, Du KT, Mihardja S, Sievers RE, Lee RJ. The effect of injected rgd modified alginate on angiogenesis and left ventricular function in a chronic rat infarct model. Biomaterials. 2009;30:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruvinov E, Leor J, Cohen S. The promotion of myocardial repair by the sequential delivery of igf-1 and hgf from an injectable alginate biomaterial in a model of acute myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2011;32:565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patra C, Talukdar S, Novoyatleva T, Velagala SR, Muhlfeld C, Kundu B, Kundu SC, Engel FB. Silk protein fibroin from antheraea mylitta for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2673–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carrier RL, Papadaki M, Rupnick M, Schoen FJ, Bursac N, Langer R, Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Cardiac tissue engineering: Cell seeding, cultivation parameters, and tissue construct characterization. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 1999;64:580–589. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990905)64:5<580::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bursac N, Papadaki M, Cohen RJ, Schoen FJ, Eisenberg SR, Carrier R, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Freed LE. Cardiac muscle tissue engineering: Toward an in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. The American journal of physiology. 1999;277:H433–444. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radisic M, Deen W, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Mathematical model of oxygen distribution in engineered cardiac tissue with parallel channel array perfused with culture medium containing oxygen carriers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1278–1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00787.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engelmayr GC, Jr, Cheng M, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE. Accordion-like honeycombs for tissue engineering of cardiac anisotropy. Nat Mater. 2008;7:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ravichandran R, Venugopal JR, Sundarrajan S, Mukherjee S, Sridhar R, Ramakrishna S. Minimally invasive injectable short nanofibers of poly(glycerol sebacate) for cardiac tissue engineering. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:385102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/38/385102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fukuhara S, Tomita S, Nakatani T, Fujisato T, Ohtsu Y, Ishida M, Yutani C, Kitamura S. Bone marrow cell-seeded biodegradable polymeric scaffold enhances angiogenesis and improves function of the infarcted heart. Circ J. 2005;69:850–857. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsubayashi K, Fedak PW, Mickle DA, Weisel RD, Ozawa T, Li RK. Improved left ventricular aneurysm repair with bioengineered vascular smooth muscle grafts. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II219–225. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087450.34497.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: Using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nature medicine. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Godier-Furnemont AF, Martens TP, Koeckert MS, Wan L, Parks J, Arai K, Zhang G, Hudson B, Homma S, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Composite scaffold provides a cell delivery platform for cardiovascular repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7974–7979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104619108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Turner WS, Wang X, Johnson S, Medberry C, Mendez J, Badylak SF, McCord MG, McCloskey KE. Cardiac tissue development for delivery of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial and cardiac cells in natural matrices. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part B, Applied biomaterials. 2012;100:2060–2072. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haraguchi Y, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Electrical coupling of cardiomyocyte sheets occurs rapidly via functional gap junction formation. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4765–4774. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sekiya S, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Bioengineered cardiac cell sheet grafts have intrinsic angiogenic potential. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;341:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hata H, Bar A, Dorfman S, Vukadinovic Z, Sawa Y, Haverich A, Hilfiker A. Engineering a novel three-dimensional contractile myocardial patch with cell sheets and decellularised matrix. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shimizu T, Sekine H, Isoi Y, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Long-term survival and growth of pulsatile myocardial tissue grafts engineered by the layering of cardiomyocyte sheets. Tissue engineering. 2006;12:499–507. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sekine H, Shimizu T, Hobo K, Sekiya S, Yang J, Yamato M, Kurosawa H, Kobayashi E, Okano T. Endothelial cell coculture within tissue-engineered cardiomyocyte sheets enhances neovascularization and improves cardiac function of ischemic hearts. Circulation. 2008;118:S145–152. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bel A, Planat-Bernard V, Saito A, Bonnevie L, Bellamy V, Sabbah L, Bellabas L, Brinon B, Vanneaux V, Pradeau P, Peyrard S, Larghero J, Pouly J, Binder P, Garcia S, Shimizu T, Sawa Y, Okano T, Bruneval P, Desnos M, Hagege AA, Casteilla L, Puceat M, Menasche P. Composite cell sheets: A further step toward safe and effective myocardial regeneration by cardiac progenitors derived from embryonic stem cells. Circulation. 2010;122:S118–123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kushida A, Yamato M, Konno C, Kikuchi A, Sakurai Y, Okano T. Decrease in culture temperature releases monolayer endothelial cell sheets together with deposited fibronectin matrix from temperature-responsive culture surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;45:355–362. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19990615)45:4<355::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Masumoto H, Matsuo T, Yamamizu K, Uosaki H, Narazaki G, Katayama S, Marui A, Shimizu T, Ikeda T, Okano T, Sakata R, Yamashita JK. Pluripotent stem cell-engineered cell sheets reassembled with defined cardiovascular populations ameliorate reduction in infarct heart function through cardiomyocyte-mediated neovascularization. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1196–1205. doi: 10.1002/stem.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stevens KR, Pabon L, Muskheli V, Murry CE. Scaffold-free human cardiac tissue patch created from embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1211–1222. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stevens KR, Kreutziger KL, Dupras SK, Korte FS, Regnier M, Muskheli V, Nourse MB, Bendixen K, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Physiological function and transplantation of scaffold-free and vascularized human cardiac muscle tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:16568–16573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908381106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matsuura K, Wada M, Shimizu T, Haraguchi Y, Sato F, Sugiyama K, Konishi K, Shiba Y, Ichikawa H, Tachibana A, Ikeda U, Yamato M, Hagiwara N, Okano T. Creation of human cardiac cell sheets using pluripotent stem cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;425:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee P, Klos M, Bollensdorff C, Hou L, Ewart P, Kamp TJ, Zhang J, Bizy A, Guerrero-Serna G, Kohl P, Jalife J, Herron TJ. Simultaneous voltage and calcium mapping of genetically purified human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac myocyte monolayers. Circulation research. 2012;110:1556–1563. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zimmermann WH, Eschenhagen T. Cardiac tissue engineering for replacement therapy. Heart failure reviews. 2003;8:259–269. doi: 10.1023/a:1024725818835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soong PL, Tiburcy M, Zimmermann WH. Cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and their assembly into engineered heart muscle. In: Bonifacino Juan S, et al., editors. Current protocols in cell biology/editorial board. Unit23. Chapter 23. 2012. p. 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gao J, Liu J, Gao Y, Wang C, Zhao Y, Chen B, Xiao Z, Miao Q, Dai J. A myocardial patch made of collagen membranes loaded with collagen-binding human vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates healing of the injured rabbit heart. Tissue engineering. Part A. 2011;17:2739–2747. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, Shansky J, Del Tatto M, Ferland P, Wang X, Vandenburgh H. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor secreted from tissue-engineered bioartificial muscles promotes localized angiogenesis. Circulation. 2001;104:594–599. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.092215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kehat I, Davis J, Tiburcy M, Accornero F, Saba-El-Leil MK, Maillet M, York AJ, Lorenz JN, Zimmermann WH, Meloche S, Molkentin JD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 regulate the balance between eccentric and concentric cardiac growth. Circulation research. 2011;108:176–183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Streckfuss-Bomeke K, Wolf F, Azizian A, Stauske M, Tiburcy M, Wagner S, Hubscher D, Dressel R, Chen S, Jende J, Wulf G, Lorenz V, Schon MP, Maier LS, Zimmermann WH, Hasenfuss G, Guan K. Comparative study of human-induced pluripotent stem cells derived from bone marrow cells, hair keratinocytes, and skin fibroblasts. European heart journal. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schaaf S, Shibamiya A, Mewe M, Eder A, Stohr A, Hirt MN, Rau T, Zimmermann WH, Conradi L, Eschenhagen T, Hansen A. Human engineered heart tissue as a versatile tool in basic research and preclinical toxicology. PloS one. 2011;6:e26397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xiong Q, Hill KL, Li Q, Suntharalingam P, Mansoor A, Wang X, Jameel MN, Zhang P, Swingen C, Kaufman DS, Zhang J. A fibrin patch-based enhanced delivery of human embryonic stem cell-derived vascular cell transplantation in a porcine model of postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Stem Cells. 2011;29:367–375. doi: 10.1002/stem.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feinberg AW, Feigel A, Shevkoplyas SS, Sheehy S, Whitesides GM, Parker KK. Muscular thin films for building actuators and powering devices. Science. 2007;317:1366–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1146885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Okano T, Yamada N, Sakai H, Sakurai Y. A novel recovery system for cultured cells using plasma-treated polystyrene dishes grafted with poly(n-isopropylacrylamide) Journal of biomedical materials research. 1993;27:1243–1251. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kushida A, Yamato M, Konno C, Kikuchi A, Sakurai Y, Okano T. Temperature-responsive culture dishes allow nonenzymatic harvest of differentiated madindarby canine kidney (mdck) cell sheets. Journal of biomedical materials research. 2000;51:216–223. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200008)51:2<216::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kelm JM, Lorber V, Snedeker JG, Schmidt D, Broggini-Tenzer A, Weisstanner M, Odermatt B, Mol A, Zund G, Hoerstrup SP. A novel concept for scaffold-free vessel tissue engineering: Self-assembly of microtissue building blocks. Journal of biotechnology. 2010;148:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kajstura J, Urbanek K, Perl S, Hosoda T, Zheng H, Ogorek B, Ferreira-Martins J, Goichberg P, Rondon-Clavo C, Sanada F, D’Amario D, Rota M, Del Monte F, Orlic D, Tisdale J, Leri A, Anversa P. Cardiomyogenesis in the adult human heart. Circulation research. 2010;107:305–315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 99.Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Role of cardiac stem cells in cardiac pathophysiology: A paradigm shift in human myocardial biology. Circulation research. 2011;109:941–961. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 100.Huntgeburth M, Tiemann K, Shahverdyan R, Schluter KD, Schreckenberg R, Gross ML, Modersheim S, Caglayan E, Muller-Ehmsen J, Ghanem A, Vantler M, Zimmermann WH, Bohm M, Rosenkranz S. Transforming growth factor beta(1) oppositely regulates the hypertrophic and contractile response to beta-adrenergic stimulation in the heart. PloS one. 2011;6:e26628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Singh BN, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry JP, Weaver CV. Heart of newt: A recipe for regeneration. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2010;3:397–409. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Werdich AA, Anderson RM, Fang Y, Egnaczyk GF, Evans T, Macrae CA, Stainier DY, Poss KD. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2010;464:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Major RJ, Blum N, Dahn RD, Begemann G, Poss KD. Retinoic acid production by endocardium and epicardium is an injury response essential for zebrafish heart regeneration. Developmental cell. 2011;20:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2013;493:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gupta V, Poss KD. Clonally dominant cardiomyocytes direct heart morphogenesis. Nature. 2012;484:479–484. doi: 10.1038/nature11045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature. 2010;464:606–609. doi: 10.1038/nature08899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Thompson SA, Burridge PW, Lipke EA, Shamblott M, Zambidis ET, Tung L. Engraftment of human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes improves conduction in an arrhythmogenic in vitro model. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2012;53:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, Nakamura T, Gaussin V, Mishina Y, Pocius J, Michael LH, Behringer RR, Garry DJ, Entman ML, Schneider MD. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martin CM, Meeson AP, Robertson SM, Hawke TJ, Richardson JA, Bates S, Goetsch SC, Gallardo TD, Garry DJ. Persistent expression of the atp-binding cassette transporter, abcg2, identifies cardiac sp cells in the developing and adult heart. Developmental biology. 2004;265:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mordwinkin NM, Burridge PW, Wu JC. A review of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for high-throughput drug discovery, cardiotoxicity screening, and publication standards. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2013;6:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9423-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, Reth M, Platoshyn O, Yuan JX, Evans S, Chien KR. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Iso Y, Spees JL, Serrano C, Bakondi B, Pochampally R, Song YH, Sobel BE, Delafontaine P, Prockop DJ. Multipotent human stromal cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction in mice without long-term engraftment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Noiseux N, Gnecchi M, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Zhang L, Solomon SD, Deb A, Dzau VJ, Pratt RE. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing akt dramatically repair infarcted myocardium and improve cardiac function despite infrequent cellular fusion or differentiation. Mol Ther. 2006;14:840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, Melo LG, Morello F, Mu H, Noiseux N, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gnecchi M, He H, Noiseux N, Liang OD, Zhang L, Morello F, Mu H, Melo LG, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Evidence supporting paracrine hypothesis for akt-modified mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cardiac protection and functional improvement. FASEB J. 2006;20:661–669. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5211com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, He H, Rezvani M, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003;9:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Murakami Y, Zhang Y, Cho YK, Mansoor AM, Chung JK, Chu C, Francis G, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ, From AH, Jerosch-Herold M, Wilke N, Zhang J. Myocardial oxygenation during high work states in hearts with postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 1999;99:942–948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang J, Merkle H, Hendrich K, Garwood M, From AH, Ugurbil K, Bache RJ. Bioenergetic abnormalities associated with severe left ventricular hypertrophy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;92:993–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI116676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, Sanada F, Elmore JB, Goichberg P, Cappetta D, Solankhi NK, Fahsah I, Rokosh DG, Slaughter MS, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (scipio): Initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 121.Tang XL, Rokosh G, Sanganalmath SK, Yuan F, Sato H, Mu J, Dai S, Li C, Chen N, Peng Y, Dawn B, Hunt G, Leri A, Kajstura J, Tiwari S, Shirk G, Anversa P, Bolli R. Intracoronary administration of cardiac progenitor cells alleviates left ventricular dysfunction in rats with a 30-day-old infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:293–305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.871905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, Czer LS, Marban L, Mendizabal A, Johnston PV, Russell SD, Schuleri KH, Lardo AC, Gerstenblith G, Marban E. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (caduceus): A prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]